أتراك

| إجمالي التعداد | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 مليون | |||||||||||||||||||||

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 55.500.000-60.500.000[1][2][3] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.500.000-4.000.000[4][5][6] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 600.000-3.300.000[7][8][9] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 500.000-3.000.000[10][11][12] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 500.000-2.400.000[13][14][15] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 750.000-1.500.000[16][17][18] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 588.000-800.000[19][20][21] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 500.000-1.000.000[22][23] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 500.000a[›][24][25][26] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 500.000 b[›][27][28][29] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 400.000-500.000 c[›][30][31][32] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 350.000-500.000[33][34][35] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 300.000-500.000 d[›][36][37] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 300.000 f[›][38] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 200.000[39][40] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 77.959-200.000[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 150.000-200.000[13][44] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 80.000-150.000 g[›][45][46][47] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 150.000 h[›][48] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 120.000-150.000[49] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 120.000 e[›][50] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 110.000 h[›][48][51][52] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 100.000-150.000 i[›][53][54] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 100.000-1.500.000[55][56] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 70.000[57] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 50.000-100.000[58][59][60] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 50.000-80.000[61][62] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 60.000[13] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 50.000[63][63] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 50.000[13] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 30.000-50.000[63][64] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 50.000 h[›][48][65] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 28.226-80.000[66][67][68] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| اللغات | |||||||||||||||||||||

| التركية | |||||||||||||||||||||

| الدين | |||||||||||||||||||||

| الأغلبية الحنفية السنية، أقلية العلوية[69] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| الجماعات العرقية ذات الصلة | |||||||||||||||||||||

| شعوب توركية أخرى، خاصة فرع الاوغوز[70] Ancestry (genetic studies): Primarily Ancient Anatolians,[71] but also neighboring peoples,[72] such as Balkan peoples,[73] بالرغم من عدم وجود روابط عرقية ولسانية؛ والشعوب التوركية[72] | |||||||||||||||||||||

الشعب التركي، أو الأتراك (تركية: Türkler)، هم جماعة عرقية توركية تنطق التركية ويعيشون بصفة رئيسية في الجمهورية التركية، وفي الأراضي التي كانت تابعة للدولة العثمانية حيث نشأت الأقليات التركية. وفي الواقع، تعتبر الأقليات التركية هي ثاني أكبر الجماعات بلغاريا وقبرص. بالإضافة غلى ذلك، ونتيجة للهجرة الحديثة، فقد نشأ شتات تركي حيث تشكلت جاليات كبرى في النمسا، بلجيكا، فرنسا، ألمانيا، هولندا، سويسرا، والمملكة المتحدة. هناك أيضاً جاليات تركية تعيش في أستراليا، الاتحاد السوڤيتي السابق وأمريكا الشمالية.

التسمية والعرقية

كلمة "ترك" فقد ذكرت لأول مرة في أعمال هيرودوت(484-425 قبل الميلاد)؛علاوة على ذلك، خلال القرن الأول الميلادي باسم "Targitas". وكان أول مصدر أكيد إلى "الأتراك" تأتي أساساً من المصادر الصينية في القرن السادس. في هذه المصادر، "الترك" ذكرت "Tujue"(بالصينية: 突厥؛ ويد–جيلز: T’u-chüe)، والتي تشير إلى غوكتورك.[74][75] على الرغم من أن "ترك" يشير إلى الشعب التركي، فإنه قد يشير أيضاً في بعض الأحيان إلى مجموعة لغوية واسعة من الشعوب التوركية.[76]

في القرن 19، وكلمة ترك أشارت فقط لقرويي الأناضول. حددت النخبة العثمانية نفسها كعثمانيون، وليس عادة كالأتراك.[77] في أواخر القرن 19، كما تبنت النخبة العثمانية الأفكار الأوروبية القومية وكما أصبح واضحا أن المتحدثين التركية في الأناضول كانوا الأكثر ولاء ومؤيدين للحكم العثماني، كما أن مصطلح ترك أخذت على مدلولاً أكثر إيجابية.[78]

في العهد العثماني نظام الملة تُحدد المجتمعات على أساس ديني، وبقايا من هذا يبقى في أن القرويين الأتراك يُنظر إليهم عادة باسم الأتراك فقط على أولئك الذين يدينون المذهب السني، والنظر للناطقين بالتركية من اليهود والمسيحيين أو حتى العلويين غير أتراكٍ.[79] ومن ناحية أخرى، فإن الناطقين بالكردية أو العربية من أهل السنة في شرق الأناضول يعتبروا في بعض الأحيان كأتراك.[80] ويمكن أيضاً أن ينظر إلى عدم الدقة في تسمية أتراك مع أسماء عرقية أخرى، مثل الأكراد، والتي غالباً ما تطلق من قبل الأناضول الغربية إلى أي شخص شرق أضنة، حتى أولئك الذين يتحدثون التركية فقط.[79] وفي السنوات الأخيرة، وقد حاول السياسيين الأتراك الوسطيين لإعادة تعريف هذه الفئة بطريقة أكثر كمتعددة الثقافات، مؤكداً أن كلمة تركى تُطلق على كل من هو مواطن من جمهورية تركيا.[81]، وفي الوقت الراهن في المادة 66 من الدستور التركي تعرف كلمة تركى فهو أي شخص "منضم إلى الدولة التركية من خلال رباط المواطنة."[82] وحالياً، يتم كتابة دستور جديد، والتي قد تعالج قضايا المواطنة والانتماء العرقي.[83]

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ، العصر القديم والعصور الوسطى المبكرة

سُكنت الاناضول لأول مرة من قبل الصيادين و جامعي الثمار خلال العصر الحجري، وفي العصور القديمة كان يسكنها مختلف من الشعوب الأناضولية القديمة.[84] و بعد غزو الإسكندر الأكبر في 334 قبل الميلاد، وكانت هذه المنطقة متأثرة بالحضارة اليونانية، وبحلول القرن الأول قبل الميلاد، فإنه يعتقد عموما أن اللغات المحلية الأناضولية قد انقرضت.[85][86][87]

في آسيا الوسطى، وأقرب النصوص التي ما زالت موجودة مكتوبة بالتركية، و نقوش أورخون في القرن الثامن، نصبت من قبل غوكتورك في القرن السادس الميلادي، وتتضمن كلمات غير شائعة لكنها وجدت في التركية لا علاقة باللغات الآسيوية الداخلية. و على الرغم من أن الأتراك القدماء كانوا من البدو الرحل، فقد تاجروا في الصوف، والجلود والسجاد، والخيول للخشب، والحرير، والخضروات والحبوب، فضلا عن وجود محطات الحدادة كبيرة في الجنوب من جبال ألتاي خلال 600 م معظم الناطقين باللغة التركية كان الناس شامانيون، و اعتنقوا عبادة "التنجرية"، وإن كانت هناك أيضا أتباع المانوية، المسيحية النسطورية، أو على وجه الخصوص البوذية.[88][89] ولما بدأت الفتوحات الإسلامية لآسيا بدأ الأتراك في اعتناق الإسلام بعد الفتح الإسلامى لبلاد ما وراء النهر من خلال جهود البعثات والصوفية والتجار. و في ذلك الوقت تحول الأتراك إلى الإسلام من خلال الثقافة الفارسية وآسيا الوسطى. و في عهد الأمويين، كان يجلب منهم كعبيد، و في عهد حكم العباسيين، قاموا بزيادة أعدادهم وتم تدريبهم كجنود.[89] بحلول القرن التاسع، وقد تولت القوات التركية التركية قيادة القوات العسكرية للخليفة في المعارك. كما رفض الخلافة العباسية تولى ضباط التركي قوة عسكرية وسياسية أكثر أو إنشاء مقاطعات خاصة بهم من القوات التركية.

عصر السلاجقة

خلال القرن 11 ميلادي استولى السلاجقة وهم أتراك على المنطقة الشرقية للخلافة العباسية، ثم تمكنوا بعد 1055 من الإستيلاء على بغداد، وخلالها كانت أول محاولات الأتراك التوغل إلى الأناضول، وبعد معركة ملاذكرد ضد البيزنطيين تمكن السلاجقة من بسط نفوذهم على أجزاء واسعة من الأناضول وبهذا انتشرت القبائل التركية في المنطقة.

تمكن السلاجقة من إنشاء دولة لهم في الأناضول وسموها سلاجقة الروم واتخذوا قونيا عاصمة لهم في 1097، وكانت خلالها الحرب الصليبية في بلاد الشام، وبحلول القرن 12 ميلادي بدأ الأوروبيون يطلقون على منطقة الأناضول بلاد الأتراك، انتشر خلالها الإسلام أيضا في المنطقة، ونتيجة لهذا حدث تزاوج وتصاهر بين الأتراك مع سكان المنطقة الذين اعتنقوا الإسلام وتمازجوا مع القادمين.

بعد اجتياح المغول للمنطقة كان من أثر ذلك أن تفككت الإمارة السلجوقية وبدأ عهد الإمارات التركمانية.

عصر البايليكات

بعد هزيمة الأتراك السلاجقة من قبل الغزو المغولي في الأناضول، وأصبح الأتراك تابعة للإيلخانية التي أسست إمبراطورية خاصة بهم في منطقة واسعة تمتد من أفغانستان ليومنا حاليا تركيا.[90] كما احتل المغول أكثر الأراضي في آسيا الصغرى، انتقل الأتراك مزيدا إلى غرب الأناضول واستقروا في الحدود السلجوقية البيزنطية.خلال العقود الأخيرة من القرن 13، فإن الإيلخانية و اتباع السلاجقة فقدوا السيطرة على جزء كبير من الأناضول من هذه الشعوب التركمانية.مع بداية القرن الرابع عشر نجح أمراء الأناضول من الوصول إلى شواطئ بحر إيجة، وهو ماتمكن منه السلاجقة سابقاً. كانت أقوى الإمارات في البداية هم القرمان وكرمايان والذين كانوا يتمركزوا في المنطقة الوسطى، في حين أن عائلة بني عثمان والذين أسسوا لاحقاً الإمبراطورية العثمانية كانو يسيطروا على منطقة عديمة الأهمية في الشمال الغربي حول سوغوت. امتدت على طول بحر إيجة من الشمال إلى الغرب الإمارات التالية: بنو قرا صي وبنو صاروخان وبنو آيدين وبنو منتشا وبنو تكة. كما حكم بنو جاندار منطقة البحر الأسود الواقعة بين قسطموني وسينوب.[91]

في الشمال الغربي من الأناضول حول Söğüt، حيث كانت ولاية عثمانية صغيرة و في هذه المرحلة كانت مهملة، وتطوقه من الشرق من القوى الأخرى الأكثر جوهرية مثل قارمان على قونية، التي حكمت من البحر الأسود إلى البحر المتوسط. على الرغم من أن العثمانيين كانت مجرد إمارة صغيرة بين العديد من إمارات الاناضول التركية، وبالتالي كانت أصغر تهديدا للسلطة البيزنطية، وموقعها في شمال غرب الأناضول في محافظة بيزنطية سابقة لبيثينيا، أصبح موقف جيدا لفتوحاتهم في المستقبل. فقد غزا اللاتين مدينة القسطنطينية في العام 1204 خلال الحملة الصليبية الرابعة، وأنشأت الإمبراطورية اللاتينية (1204-1261)، وتنقسم الأراضي البيزنطية السابقة في البلقان و فيما بينها بحر إيجه ، واضطر الأباطرة البيزنطيين إلى أن يكونوا في حالة منفى في نيقية (في الوقت الحاضر إزنيق).و من 1261 فصاعدا، والبيزنطيين كان مشغولين إلى حد كبير باستعادة سيطرتهم في منطقة البلقان. في أواخر القرن 13th، عندما بدأ المغول السلطة في الانخفاض، تولى قادة التركمان قدر أكبر من الاستقلالية.[92]

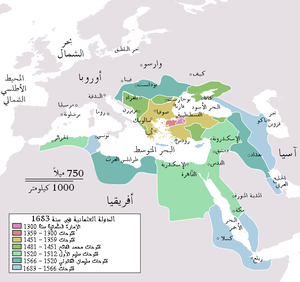

العصر العثماني

في عهد عثمان الأول، والإمارة العثمانية توسعت على طول نهر ساكاريا وغربا باتجاه بحر مرمرة. وبالتالي، كان سكان غرب آسيا الصغرى أصبحوا إلى حد كبير يتحدثون باللغة التركية ومعتنقين الإسلام.و في عهد ابنه، أورخان الأول، الذي كان قد هاجم واحتل المركز الحضري هاما لبورصة سنة 1326، معلنا أنها العاصمة العثمانية، كما أن الإمبراطورية العثمانية بدأت تطور تطورا كبيرا.و في عام 1354، دخل العثمانيين في أوروباوأسسوا موطئ قدم في شبه جزيرة جاليبولي وفي الوقت نفسه اندفعوا إلى الشرق واخذوا أنقرة.[93][94] و قد بدأ العديد من أتراك الأناضول ليستقروا في المناطق التي تركها السكان الذين فروا تراقيا قبل الغزو العثماني.[95] ومع ذلك، كان البيزنطيين ليسوا وحدهم من يعاني من النهوض العثماني في منتصف 1330، و قد ضم أورخان بعد ذلك الامارة التركية بنو قرا صي. واستمر هذا التقدم بواسطة مراد الأول الذي كان سيطرته على أكثر من ثلاثة أضعاف الأراضي الواقعة حيث كانوا تحت حكمه المباشر، ليصل إلى حوالي 100،000 ميل مربع، موزعة بالتساوي في أوروبا وآسيا الصغرى.فكانت المكاسب في الأناضول كانت مطابقة من لما احزوه في أوروبا؛ و بمجرد أخذت القوات العثمانية أدرنة، والتي أصبحت عاصمة للإمبراطورية العثمانية عام 1365، ففتحوا طريقا داخل بلغاريا ومقدونيا في 1371 في معركة ماريتزا.[96] و مع تلك الفتوحات في تراقيا ومقدونيا وبلغاريا، فإن أعدادا كبيرة من المهاجرين الأتراك واستقروا في هذه المناطق.[95] وأصبح هذا الشكل من أشكال التوطين العثماني التركي وسيلة فعالة جدا لتعزيز مكانتها وقوتها في منطقة البلقان. وتألف المستوطنين من الجنود، والبدو والمزارعين والحرفيين والتجار والدراويش والدعاة و رجال الدين من الاديان الأخرى، والموظفين الإداريين.[97]

قامت الجيوش العثمانية في عهد السلطان محمد الثاني بفتح القسطنطينية في عام 1453. و بعدها قام محمد الفاتح بإعادة بناء وإسكان في المدينة، وجعلها عاصمة العثمانية الجديدة. و بعد سقوط القسطنطينية دخلت الدولة العثمانية لفترة طويلة من الفتوحات والتوسع في حدودها وفي نهاية المطاف ذهبت عميقا في أوروبا والشرق الأوسط، وشمال أفريقيا.[98] و بعدها توسع سليم الأول بشكل كبير في الحدود الشرقية والجنوبية للإمبراطورية في معركة جالديران، واكتسبت الاعتراف الوصي على المدينتين المقدستين مكة المكرمة والمدينة المنورة.و بعدها خلفه ابنه سليمان القانوني، توسّع كذلك الفتوحات بعد الاستيلاء بلغراد عام 1521 واستخدام قاعدتها الإقليمية لغزو المجر، والأراضي الأخرى في أوروبا الوسطى، بعد انتصاره في معركة موهاج وكذلك أيضا دفع حدود الامبراطورية للشرق.[99] وبعد وفاة سليمان واصلت الانتصارات العثمانية، وإن كان أقل كثيرا من ذي قبل. و تم فتح جزيرة قبرص، في 1571، تعزيزا للهيمنة العثمانية على الطرق البحرية في شرق البحر الأبيض المتوسط.[100] ومع ذلك، وبعد هزيمتها في معركة فيينا، عام 1683، وكان في استقبال الجيش العثماني عن طريق الكمائن ومزيد من الهزائم؛1699 من معاهدة كارلوفجة، الذي منح النمسا محافظات المجر وترانسلفانيا، هذه هي المرة الأولى في التاريخ أن الإمبراطورية العثمانية تخلت في الواقع الأراضي.[101] و بحلول القرن 19، بدأت الامبراطورية في الضعف عندما وقع الانتفاضات القومية العرقية عبر الإمبراطورية. وبالتالي، شهد الربع الأخير من 19 وأوائل القرن 20 بعض 7-9 ملايين من اللاجئين الأتراك المسلمين من الأراضي المفقودة من القوقاز والقرم، البلقان، وجزر البحر الأبيض المتوسط الهجرة إلى الأناضول وتراقيا الشرقية.[102] و في عام 1913، بدأت حكومة جمعية الاتحاد والترقي وضع برنامج التتريك القسري للأقليات غير التركية.[103][104] وبحلول عام 1914 ،اندلعت الحرب العالمية الأولى، وسجل الأتراك بعض النجاح في جاليبولي أثناء معركة الدردنيل في عام 1915 وخلال الحرب العالمية الأولى. و في عام 1918 فإن الأتراك الممثل في جمعية الاتحاد والترقي، وافقوا على هدنة مع انكلترا وفرنسا.

كما وقعت حكومة محمد السادس معاهدة سيفر في عام 1920 تفكيك الامبراطورية العثمانية. و لكن مصطفى كمال أتاتورك رفض قبول شروط المعاهدة وخاضت حرب الاستقلال التركية، مما أدى إلى إلغاء السلطنة. وهكذا، انتهت الإمبراطورية العثمانية سنوات 623 القديمة.[105]

العصر الحديث

بقيادة مصطفى كمال أتاتورك حرب الاستقلال التركية ضد قوات الحلفاء التي احتلت الإمبراطورية العثمانية السابقة، فوحد الأغلبية المسلمة من الأتراك. قاد بنجاح في هذه الحرب الشعب التركى 1919-1922 في إسقاط قوات الاحتلال للخروج من ما اعتبرته الحركة الوطنية التركية الوطن التركي.[106] وأصبحت الهوية التركية في قوة موحدة في عام 1923، وتم التوقيع على معاهدة لوزان وتأسست جمهورية تركيا رسميا.فقد كان فترة حكم أتاتورك لمدة 15 عاما من خلال سلسلة من الإصلاحات السياسية والاجتماعية الراديكالية التي حولت تركيا إلى العلمانية الجمهورية الحديثة مع المساواة المدنية والسياسية للأقليات طائفية والنساء.[107]

وعلى مدار 1920 و1930، فكان الأتراك وكذلك غيرهم من المسلمين، من البلقان، البحر الأسود، وجزر بحر ايجه وجزيرة قبرص، ولواء إسكندرون (هاتاي)، والشرق الأوسط، والاتحاد السوفيتي ليصل و يستقر معظمهم في تركيا وفي الحضر شمال غرب الأناضول.[108][109] لكن القسم الأكبر من هؤلاء المهاجرين والمعروفين باسم "المهاجرين"من أتراك البلقان واجهوا كثيرا من المضايقات والتمييز في أوطانهم.[108] ومع ذلك، لا زال هناك عددا جيدا من السكان الأتراك في العديد من هذه البلدان، لأن الحكومة التركية أرادت الحفاظ على هذه المجتمعات حتى يمكن الحفاظ على الطابع التركي من هذه الأراضي المجاورة.[110] و واحدة من هذه الهجرات للأتراك في المراحل الأخيرة إلى تركيا بين عامي 1940 و 1990 حتى وصل عددهم حوالي 700،000 من أتراك بلغاريا. وحاليا يمثل أحفاد هؤلاء المهاجرين ما بين ثلث وربع سكان تركيا.[109]

الجينات الوراثية

مقالة مفصلة: التاريخ الوراثي للأتراك

مقالة مفصلة: التاريخ الوراثي للأتراك

خلال الحقبة الرومانية المتأخرة، قبل الفتح التركي كان سكان الأناضول قدر عددهم بأكثر من 12 مليون نسمة.[111][112][113] علاوة على ذلك، في وقت الهجرات التركية كانت الأناضول أقل نسبة للمهاجرين الذين يستطونون بها.[114] إن مدى تدفق الجينات من آسيا الوسطى متصلة إلى الجينات الحالية للشعب التركي، ودور الغزو من قبل الشعوب التركية في القرن 11th، حيث كانت موضع دراسات مختلفة. وقد توصلت العديد من الدراسات إلى أن مجتمعات الأناضول التاريخية والأصلية هي المصدر الرئيسي لللشعب التركي في الوقت الحاضر.[71]k[›][115][116][117][118] علاوة على ذلك، اقترحت الدراسات المختلفة التي، على الرغم من أن الغزاة الأتراك في وقت مبكر اجروا غزواً من الناحية الثقافية، بما في ذلك إدخال اللغة التركية القديمة الأناضولية(القديمة إلى التركية الحديثة) والإسلام، ولكن كانت المساهمة الوراثية من آسيا الوسطى قد تكون صغيرة جدا.k[›][115][119] وأصبح الشعب التركي اليوم يرتبط بشكل وثيق مع سكان بلقان أكثر من شعوب آسيا الوسطى,[114][73] و هناك بحث يظهر من خلال فحص ترددات الاليل عدم وجود علاقة وراثية بين المغول والأتراك، على الرغم من العلاقة التاريخية للغاتهم (الأتراك والألمان كانوا بعيدين بالتساوي من جميع سكان منغوليا الثلاثة).[120] أشارت دراسات متعددة إلى نخبة من هيمنة ثقافية لغوية قائمة على نموذج بديل لشرح اتخاذ التركية لغة للسكان الأصليين في الأناضول.[71]k[›][118] وهناك دراسة شملت تحليل عينات الميتوكوندريا من سكان العصر البيزنطي، الذي تم جمعها من الحفريات في الموقع الأثري في Sagalassos، وجد أن العينات الوراثية بها تقارب وثيق مع السكان الحداث من الأتراك والبلقان.[121] وخلال أبحاثهم على سرطان الدم، لاحظ مجموعة من العلماء الأرمن مطابقة الجينية عالية بين الأتراك والأكراد، والأرمن.[122] ووجدت دراسة أخرى أن الأديغة (الشركس) من القوقاز الأقرب إلى الشعب التركي بين عينات الأوروبية (الفرنسية والإيطالية)، الشرق الأوسط (الدروز والفلسطينيين)، ووسط (قيرغيزستان والهزارة، والويغور)، وجنوب (باكستان)، والشرق الآسيوية (المنغولية، هان) السكان.[72]

التوزيع الجغرافي

المناطق التقليدية للاستيطان التركي

تركيا

العرقية التركية يشكلون ما بين 70٪ إلى 75٪ من سكان تركيا.[123]

قبرص

القبارصة الأتراك هم أتراك العرقية أسلاف الأتراك العثمانيين, استعمرت جزيرة قبرص في 1571. وأعطت الدولة العثمانية 30،000 جندي تركي الأراضي هناك و استقروا في قبرص. و في عام 1960، كشفت عن وجود تعداد من قبل حكومة الجمهورية الجديدة أن القبارصة الأتراك شكلوا 18.2٪ من سكان الجزيرة.[124] و بعدها وقع اقتتال طائفي وتوترات عرقية بين القبارصة الأتراك واليونانيين بين عامي 1963 و 1974 ، والمعروفة باسم "صراع قبرص"، أجرت الحكومة القبرصية اليونانية تعداد في عام 1973، وإن كان دون الجماهير القبرصية التركية. وبعد سنة، في عام 1974، قدرت إدارة الحكومة القبرصية للإحصاءات وبحوث كان عدد السكان القبارصة الأتراك 118،000 (18.4٪).[125] وأعقب انقلاب في قبرص يوم 15 يوليو تموز 1974 من قبل اليونانيين والقبارصة اليونانيين لصالح الاتحاد مع اليونان (المعروف أيضا باسم "إينوسيس") بالتدخل العسكري من قبل تركيا التي فرضت سيطرتها على قبرص التركية على الجزء الشمالي من الجزيرة.[126] وبالتالي، التعداد الذي أجرته جمهورية قبرص التي استبعدت السكان القبارصة الأتراك أن استقروا في جمهورية التركية لشمال قبرص غير المعترف بها, و بين عامي 1975 و 1981، شجعت تركيا مواطنيها ليستقروا في قبرص الشمالية؛ اقترح تقرير صادر عن مجموعة الأزمات الدولية لعام 2010 أن من بين 300،000 من السكان الذين يعيشون في شمال قبرص ربما نصف من ولدوا إما في تركيا أو هم من الأطفال من مثل المستوطنين.[127]

البلقان

| أماكن التواجد | عام تواجدهم | اسم الجالية التركية | الأوضاع الجارية |

|---|---|---|---|

| البوسنة والهرسك | 1463 | أتراك البوسنة | وأظهر التعداد البوسنى عام 1991 أن هناك أقلية من 267 تركى.[128]

لكن التقديرات الحالية تشير إلى أن هناك بالفعل 50،000 الأتراك الذين يعيشون في البلاد. |

| بلغاريا | 1396 | أتراك بلغاريا | في عام 2011 تعداد البلغاري، التي لم تتلق ردا بشأن العرق من مجموع السكان، 588318 شخص، أو 8.8٪ من تحديد انتمائهم العرقي كما نصبوا أنفسهم التركية[129]؛ في حين أن آخر تعداد للسكان في كامل سجلت تعداد 2001 746664 الأتراك، أو 9.4٪ من السكان.[130] تقديرات أخرى تشير إلى أن هناك 750،000 لتصل إلى حوالي 1 مليون تركي في البلاد.[131] |

| كرواتيا | 1526 | أتراك كرواتيا | وفقا للتعداد السكانى في كرواتيا عام 2001 أن الأقلية التركية بلغت 300تركى.وأكثر التقديرات الأخيرة اشارت أن هناك 2،000 الأتراك في كرواتيا. |

| اليونان | 1523 | أتراك الدوديكانيز | يعيش نحو 5،000 تركى في جزر دوديكانيز رودس وكوس.[132] |

| جمهورية كوسوڤو | 1389 | أتراك كسوڤو[133] | هناك ما يقرب من 50،000 من الكوسوڤيين الأتراك الذين يعيشون في كوسوفو معظمهم في ماموشا، بريزرن،و بريشتينا. |

| جمهورية مقدونيا | 1392 | أتراك مقدونيا[134] | ينص الإحصاء المقدوني للتعداد السكانى عام 2002 أن هناك 77,959 تركى مقدوني، وتشكيل حوالي 4٪ من مجموع السكان وتشكل أغلبية في مركز جوبا وبلاسنيكا.[41] ومع ذلك، تشير التقديرات الأكاديمية التي كانت في الواقع بين عدد 170،000-200،000.[20][43] وعلاوة على ذلك، فقد هاجر حوالي 200،000 المقدونية الأتراك إلى تركيا خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى والحرب العالمية الثانية بسبب الاضطهاد والتمييز. |

| الجبل الأسود | 1496 | أتراك الجبل الأسود | وفقا لتعداد عام 2011 كان يوجد104 تركياً في الجبل الأسود.[135] غالبيتهم تركوا ديارهم وهاجروا إلى تركيا في 1900.[136] |

| دوبروجا, رومانيا | 1388 | أتراك رومانيا[137] | وفقا لتعداد عام 2011 الرومانية كان هناك 28،226 من أتراك رومانيا مقيمون في البلاد.[66] ومع ذلك، تشير التقديرات إلى أن الأعداد التي أشارت إليها الدراسات بين 55،000[63][67] و 80،000.[68] |

| تراقيا الغربية، اليونان | 1354 | أتراك تراقيا الغربية | الحكومة اليونانية عمدا تشير إلى المجتمع به "مسلمين اليونان" أو "الهيلينيين المسلمين" وتنفي وجود أقلية التركية في تراقيا الغربية، في الجزء الشرقي من شمال اليونان،[138] وكانت التقديرات السكانية اشارت بوجود الاتراك ما بين 120،000-130،000،ولكن التقديرات الحديثة اشارت بلغ عددهم 150،000. كما أن ما بين 300،000 إلى 400،000 هاجروا إلى تركيا منذ عام 1923. |

المشرق العربي

| الأتراك في المشرق | |||||||

| البلد | بدء الاستيطان | اسم الجالية التركية | الوضع الحالي | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| العراق | 1534 | الأتراك العراقيون | عادة ما يطلق على الأتراك في العراق "التركمان العراقيون" بسبب الهجرات التوركية المختلفة والتي بدأت في أوائل القرن السابع. ومع ذلك فمعظم أحفاد المهاجرين الأوائل قد اندمجوا مع السكان العرب المحليين.[139] بغزو سليمان القانوني العراق عام 1534، بعد استيلاء السلطان مراد الرابع على بغداد عام 1638، تدفقت أعداد كبيرة من الأتراك إلى المنطقة.[140][141][142] معظم التركمان العراقيون اليوم من أحفاد الجنود العثمانيين، التجار، والموظفين المدنيين الذين جائوا إلى العراق أثناء الحكم العثماني.[143][144][140][142] | ||||

| الأردن | 1516 | أتراك أردنيون | توجد أقلية صغيرة من الأتراك في الأردن تقدر بحوالي 5.000 شخص وهو أحفاد المستعمرون العثمانيين الأتراك.[145] | ||||

| لبنان | 1516 | أتراك لبنانيون | يبلغ عدد الجالية التركية في لبنان حالياً حوالي 80.000 شخص.[61] أتى الأتراك للمنطقة بصحبة جيش السلطان سليم الأول أثناء حملته على [بمصر]]. أحفاد المستوطنون الأتراك العثمانيين الأوائل يعيشون بصفة أساسية في عكار و[بعلبك]].[146] استمرت الهجرة العثمانية التركية بعدما فقدت الدولة العثمانية هيمنتها على جزيرة كريت، في اليونان المعاصرة.[147] بعد 1897، عندما فقدت الدولة العثمانية سيطرتها على الجزيرة، أرسلت سفن عثمانية لحماية الأتراك الكريتيون، وأقام معظمهم في إزمير ومرسين، لكن بعضهم أُرسل إلى طرابلس، لبنان.[147] | ||||

| سوريا | 1516 | أتراك سوريون | عادة ما يطلق على الأتراك في سوريا "التركمان السوريون" بسبب الهجرات التوركية المختلفة إلى سوريا والتي بدأت في أوائل القرن السابع عشر، ومع ذلك فأحفاد هؤلاء المهاجرون الأوائل قد إندمجوا مع الشعوب العربية. عام 1516 غزا السلطان سليم الأول سوريا وأصبحت المنطقة جزءاً من الدولة العثمانية حتى 1918.[148] ومن ثم، فطوال سنوات الحكم التركي-العثماني ال402، هاجر الأتراك من الأناضول لسوريا لمئات السنين، مؤسسين لأنفسهم جالية بارزة.[149] اليوم يوجد حوالي 1.5 مليون تركي يعيش في سوريا ولا يزالوا يتحدثون التركية، بالرغم من أن هناك أكثر من 2 مليون آخرين يعتقد أنهم اندمجوا في الشعب العربي.[150] | ||||

مشكتيا

شمال أفريقيا

| الأتراك في شمال أفريقيا | |||||||

| البلد | بدء الاستيطان | اسم الجالية التركية | الوضع الحالي | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الجزائر | 1517 | أتراك جزائريون | تتفاوت تقديرات الجالية التركية في الجزائر، وحسب السفارة التركية بالجزائر فهناك من 600.000 إلى 2 مليون شخص من أصل تركي يعيش في الجزائر.[7] اقترحت اوكسفورد بيزنس گروپ أن الشعوب ذات الأصول التركية تشكل 5% من إجمالي سكان الجزائر، أي حوالي 1.7 مليون.[8] غير أنه، هناك تقديرات حكومية أخرى بأن الجالية التركية تشكل أكثر من 10-25% من إجمال السكان في الجزائر.[151][152] | ||||

| مصر | 1517 | أتراك مصريون | حوالي 100.000[55] لا يزال الأتراك يعيشون في مصر وعادة ما بسبب الهجرات التوركية المختلفة لمصر والتي بدأت في أوائل القرن السابع. ومع ذلك، فمعظم أحفادهم اليوم وهم حوالي 1.5 مليون شخص يعتقد أنهم اندمجوا في الشعوب العربية.[56] | ||||

| ليبيا | 1551 | أتراك ليبيون | عام 1936 كان هناك 35.000 تركي في ليبيا، وكانوا يشكلون 5% من إجمالي السكان في ذلك الوقت.[153] | ||||

| تونس | 1574 | أتراك توانسة | 25% من إجمالي السكان التوانسة من أصل تركي.[152] | ||||

الشتات المعاصر

غرب اوروپا

أمريكا الشمالية

اوقيانوسيا

الاتحاد السوڤيتي السابق

الثقافة

العمارة

بلغت العمارة التركية ذروتها خلال الفترة العثمانية. العمارة العثمانية، متأثرة بالسلاجقة وبالبيزنطيين والعمارة الإسلامية، وجاء إلى تطوير نمط كل من تلقاء نفسها.[156] وقد وصفت العمارة العثمانية بمثابة تجميع للتقاليد المعمارية لمنطقة البحر الأبيض المتوسط والشرق الأوسط.[157]

الأدب والموسيقى

تحولت تركيا ثقافياً من الإمبراطورية العثمانية القائمة على أساس الدين إلى الدولة القومية الحديثة مع الفصل القوي جدا بين الدين والدولة، تلاها زيادة في وسائط التعبير الفنية. خلال السنوات الأولى للجمهورية، استثمرت الحكومة كمية كبيرة من الموارد في الفنون الجميلة؛ مثل المتاحف والمسارح ودور الأوبرا والهندسة المعمارية. العوامل التاريخية المتنوعة تلعب دورا هاما في تحديد هوية التركية الحديثة. الثقافة التركية هي نتاج جهود لتكون دولة غربية "حديثة"، مع الحفاظ على القيم الدينية والتاريخية التقليدية.[158] كما أن المزيج من التأثيرات الثقافية جعلتها أكثر دارمية، في شكل، على سبيل المثال "رموز جديدة من تصادم وتضافر الحضارات" الذي صدر في أعمال أورهان باموق، الحائز على جائزة نوبل 2006 في الأدب.[159]

الموسيقى التركية الكلاسيكية تشمل الأرابسك، الموسيقى الفولكلورية التركية (الموسيقى الشعبية)، فاسل، والموسيقى الكلاسيكية العثمانية (الموسيقى سانات) التي تنبع من البلاط العثماني.[160]الموسيقى التركية المعاصرة وتشمل الموسيقى البوب والروك التركية ، والهيب هوب التركية.[161]

اللغات

اللغة الرسمية هي اللغة التركية، كما يتحدث بها حوالي 77% من سكان البلاد. اللغة الكردية تستعمل بين أبناء الأقلية الكردية (حوالي 20%)، حوالي 2% ما زالوا يتكلمون اللغة العربية بين الأتراك ذوي الأصول العربية. اللغات الأخرى هي لغات الأقليات المتواجدة في البلاد: الآرامية، الأرمينية، الألبانية، الجورجية، اليونانية، اللازية و الشركسية. هناك عدة لهجات للغة التركية، تختلف بحسب المنطقة المتدوالة بها. اللغات الانجليزية و الألمانية و الفرنسية منتشرة وخاصة بين الطبقة العليا وفي المدن الكبرى وفي المناطق السياحية. تنتشر اللغة الألمانية بين الطبقة العاملة، التي عملت يوما ما في ألمانيا.

الديانات

يدين غالبية سكان تركيا بالديانة الإسلامية، حسب الإحصاءات الرسمية فإن ذلك يشكل 99،8% من سكان البلاد. حوالي 60-70% منهم يتبعون الطائفة السنية، بينما زهاء 20-30% يتبعون الطائفة العلوية. كما يدين حوالي 0،2% بالمسيحية و خاصة الأرثوذكسية، و 0،04% باليهودية. كان المسيحيون يشكلون حوالي ما نسبته 20% من سكان أراضي تركيا الحالية في بداية القرن العشرين.

نص المادة 24 من دستور عام 1982 يشير إلى أن مسألة العبادة هي مسألة شخصية فردية. لذا لا تتمتع الجماعات أو المنظمات الدينية بأي مزايا دستورية. هذا الموقف و تطبيق العلمانية بشكل عام في تركيا نبع من الفكر الكمالي، الذي ينسب لمؤسس تركيا الحديثة كمال أتاتورك الداعي للعلمانية وفصل الدين عن الدولة. المنشآت الإسلامية و رجال الدين يتم إدارتهم من قبل دائرة المسائل الدينية (Diyanet İşleri Bakanlığı). تقوم بتوظيف حوالي مئة ألف إمام و مؤذن وشيخ دعوة، كما تقوم بصيانة و إنشاء المساجد. لا يتم دعم منظمات الديانات الأخرى بشكل رسمي، ولكنهم في المقابل يتمتعوا بإدارة ذاتية و حرية العمل.

انظر أيضاً

المصادر والهوامش

^ a: According to the Home Affairs Committee this includes 300,000 Turkish Cypriots.[154] However, some estimates suggest that the Turkish Cypriot community in the UK has reached between 350,000[162] to 400,000.[163][164]

^ b: Government immigration figures on the number of Turks in the US estimates a total of 190,000 persons;[165] however, these statistics are not fully reliable because a considerable number of Turks were born in the Balkans and USSR.[166]

^ c: A further 10,000-30,000 people from Bulgaria live in the Netherlands. The majority are Bulgarian Turks and are the fastest-growing group of immigrants in the Netherlands.[167]

^ d: This includes Turkish settlers. A further 2,000 Turkish Cypriots currently reside in the southern part of the island.[168]

^ e: This figure only includes Turkish citizens. Therefore, this also includes ethnic minorities from Turkey; however, it does not include ethnic Turks who have either been born and/or have become naturalised citizens. Furthermore, these figures do not include ethnic Turkish minorities from Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece, Iraq, Kosovo, Macedonia, Romania or any other traditional area of Turkish settlement because they are registered as citizens from the country they have immigrated from rather than their ethnic Turkish identity.

^ f: This figure only includes the Turkish community in Melbourne. The 2006 Australian Census shows only 59,402 people in Australia who claimed to be of Turkish ancestry.[169] However, it neglects to include the Australian-born Turks and only identifies the number of Turkish immigrants from تركيا, Cyprus (excluding TRNC citizens), and Bulgaria. Estimates by the Sydney Morning Herald,[170] the Presidency of the Republic of Turkey,[171] as well as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development,[172] place the Turkish Australians population at 150,000 whilst the Turkish Cypriot Australian community is believed to number between 40,000-120,000.[173][174][175][176] Smaller groups of Turks have also arrive from Greece and the Republic of Macedonia.[177]

^ g: This figure only includes Turks of Western Thrace. A further 5,000 live in the Rhodes and Kos.[178] In addition to this, 8,297 immigrants live in Greece.[179]

^ h: These figures only include the Meskhetian Turks. According to offical census's there were 38,000 Turks in Azerbaijan (2009),[180] 97,015 in Kazakhstan (2009),[181] 39,133 in Kyrgyzstan (2009),[182] 109,883 in Russia (2010),[183] and 9,180 in Ukraine (2001).[184] A further 106,302 Turks were recorded in Uzbekistan's last census in 1989[185] although the majority left for Azerbaijan and Russia during the 1989 pogroms in the Ferghana Valley. Official data regarding the Turks in the former Soviet Union is unlikely to provide a true indication of their population as many have been registered as "Azeri", "Kazakh", "Kyrgyz", and "Uzbek".[186] In Kazakhstan only a third of them were recorded as Turks, the rest had been arbitrarily declared members of other ethnic groups.[187][188] Similarly, in Azerbaijan, much of the community is officially registered as "Azerbaijani"[189] even though the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported, in 1999, that 100,000 Meskhetian Turks were living there.[51]

^ i: A further 30,000 Bulgarian Turks live in Sweden.[190]

^ j: "The history of Turkey encompasses, first, the history of Anatolia before the coming of the Turks and of the civilizations--Hittite, Thracian, Hellenistic, and Byzantine--of which the Turkish nation is the heir by assimilation or example. Second, it includes the history of the Turkish peoples, including the Seljuks, who brought Islam and the Turkish language to Anatolia. Third, it is the history of the Ottoman Empire, a vast, cosmopolitan, pan-Islamic state that developed from a small Turkish amirate in Anatolia and that for centuries was a world power."[191]

^ k: The Turks are also defined by the country of origin. Turkey, once Asia Minor or Anatolia, has a very long and complex history. It was one of the major regions of agricultural development in the early Neolithic and may have been the place of origin and spread of lndo-European languages at that time. The Turkish language was imposed on a predominantly lndo-European-speaking population (Greek being the official language of the Byzantine empire), and genetically there is very little difference between Turkey and the neighboring countries. The number of Turkish invaders was probably rather small and was genetically diluted by the large number of aborigines.[192]

^ l: "It also offers us a most parsimonious, if not unanticipated, explanation of Turk ethnogenesis: the vast pre-Turkic-speaking populations of Anatolia and Siberia came to be called Turkish or Turkic due to various large-scale language- and culture-shifts beginning in the European Middle Ages and not ending until the early twentieth century." (p.32)[71]

- ^ Milliyet. "55 milyon kişi 'etnik olarak' Türk". Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division. "Country Profile: Turkey" (PDF). Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ CIA. "The World Factbook". Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ European Institute. "Merkel Stokes Immigration Debate in Germany". Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ أ ب Kötter et al. 2003, 55.

- ^ أ ب Haviland et al. 2010, 675.

- ^ أ ب Turkish Embassy in Algeria 2008, 4.

- ^ أ ب Oxford Business Group 2008, 10.

- ^ Zaman. "Türk'ün Cezayir'deki lakabı: Hıyarunnas!". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Park 2005, 37.

- ^ Phillips 2006, 112.

- ^ Taylor 2004, 28.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Akar 1993, 95.

- ^ Zaman. "Türk işadamları Tunus'ta yatırım imkanı aradı". Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Ertan, Fikret (1998), Tunus ve tarih, Zaman, http://arsiv.zaman.com.tr//1998/05/06/yazarlar/11.html.

- ^ Özkaya 2007, 112.

- ^ Internetional Strategic Research Organisation, An Aspect that Gets Overlooked: The Turks of Syria and Turkey, http://www.usak.org.tr/EN/myazdir.asp?id=2784, retrieved on 2 February 2013.

- ^ A unified Syria without Assad is what Turkmen are after, http://www.todayszaman.com/news-289267-a-unified-syria-without-assad-is-what-turkmen--are-after.html=, retrieved on 2 February 2013.

- ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2011). "2011 Population Census in the Republic of Bulgaria (Final data)" (PDF). National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria.

- ^ أ ب Sosyal 2011, 369.

- ^ Bokova 2010, 170.

- ^ Leveau & Hunter 2002, 6.

- ^ Fransa Diyanet İşleri Türk İslam Birliği. "2011 YILI DİTİB KADIN KOLLARI GENEL TOPLANTISI PARİS DİTİB'DE YAPILDI". Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ Home Affairs Committee 2011, 38

- ^ "UK immigration analysis needed on Turkish legal migration, say MPs". The Guardian. 1 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Federation of Turkish Associations UK (19 June 2008). "Short history of the Federation of Turkish Associations in UK". Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. "Immigration and Ethnicity: Turks". Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ The Washington Diplomat. "Census Takes Aim to Tally'Hard to Count' Populations". Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ Farkas 2003, 40.

- ^ Netherlands Info Services. "Dutch Queen Tells Turkey 'First Steps Taken' On EU Membership Road". Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ Dutch News. "Dutch Turks swindled, AFM to investigate". Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi 2008, 11.

- ^ "Turkey's ambassador to Austria prompts immigration spat". BBC News. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Andreas Mölzer. "In Österreich leben geschätzte 500.000 Türken, aber kaum mehr als 10–12.000 Slowenen". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ CBN. "Turkey's Islamic Ambitions Grip Austria". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ International Crisis Group 2010, 2.

- ^ Ilican 2011, 95.

- ^ "Avustralya'dan THY'ye çağrı var". Milliyet. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ King Baudouin Foundation 2008, 5.

- ^ De Morgen. "Koning Boudewijnstichting doorprikt clichés rond Belgische Turken". Retrieved 15 November 2010.

- ^ أ ب Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office 2005, 34.

- ^ Knowlton 2005, 66.

- ^ أ ب Abrahams 1996, 53.

- ^ Karpat 2004, 12.

- ^ "Demographics of Greece". European Union National Languages. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ^ Whitman 1990, i.

- ^ Ergener & Ergener 2002, 106.

- ^ أ ب ت Aydıngün et al. 2006, 13.

- ^ Ryazantsev 2009, 172.

- ^ The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation. "Diaspora und Migrantengemeinschaften aus der Türkei in der Schweiz" (PDF). Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ أ ب UNHCR 1999, 14.

- ^ NATO Parliamentary Assembly. "Minorities in the South Caucasus: Factor of Instability?". Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. "Turkiet är en viktig bro mellan Öst och Väst". Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ "Businessman invites Swedes for cheap labor, regional access". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ أ ب Baedeker 2000, lviii.

- ^ أ ب Akar 1993, 94.

- ^ DR Online. "Tyrkisk afstand fra Islamisk Trossamfund". Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ Canada's National Statistical Agency. "Statistics Canada". Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Turkish Embassy (Ottawa Canada). "Turkish-Canadian Relations". Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ^ Zaman. "Buyurun Kanada'ya uçalım". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ أ ب Al-Akhbar. "Lebanese Turks Seek Political and Social Recognition". Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Tension adds to existing wounds in Lebanon". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Sosyal 2011, 368. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Sosyal 2011 loc=368" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ OSCE 2010, 3.

- ^ IRIN Asia. "KYRGYZSTAN: Focus on Mesketian Turks". Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ أ ب National Institute of Statistics 2011, 10. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Romanian National Institute of Statistics 2011 loc=10" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب Phinnemore 2006, 157.

- ^ أ ب Constantin, Goschin & Dragusin 2008, 59. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Constantin et al 2006 loc=59" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ "Religion, Secularism and the Veil in Daily Life Survey" (PDF). Konda Arastirma. September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa: Thus Turks include the Turks of Turkey, the Azeris of Azerbaijan, and the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Turkmen, and Uzbeks of Central Asia, as well as many smaller groups in Asia speaking Turkic languages. [1]

- ^ أ ب ت ث DOI:10.2753/AAE1061-1959500101

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Yardumian_et_al" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب ت DOI:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00701.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ أ ب DOI:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00080.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ Stokes & Gorman 2010, 707.

- ^ Findley 2005, 21.

- ^ "Turk, n.1". OED Online. September 2012. Oxford University Press. 2 November 2012 <http://www.oed.com>

- ^ (Kushner 1997: 219; Meeker 1971: 322)

- ^ (Kushner 1997: 220–221)

- ^ أ ب (Meeker 1971: 322)

- ^ (Meeker 1971: 323)

- ^ (Kushner 1997: 230)

- ^ "Turkish Citizenship Law" (PDF). 29 May 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "BDP won't object to 'Turkishness' in constitution, says Türk". TODAY'S ZAMAN. 21 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ Stokes & Gorman 2010, 721.

- ^ Theo van den Hout (27 October 2011). The Elements of Hittite. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-139-50178-1. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Sharon R. Steadman; Gregory McMahon (15 September 2011). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537614-2. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ^ Carlos Quiles, Fernando López-Menchero (5 October 2009). A Grammar of Modern Indo-European, Second Edition: Language and Culture, Writing System and Phonology, Morphology, Syntax, Texts and Dictionary. Indo-European Association. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-1-4486-8206-5. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Frederik Coene, The Caucasus-An Introduction, p.77 Taylor & Francis, 2009

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLeiser 2005 loc=837 - ^ Duiker & Spielvogel 2012, 192.

- ^ (limited preview) Kate Fleet (1999). European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State: The Merchants of Genoa and Turkey ISBN 0-521-64221-3. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Kia 2011, 1.

- ^ Fleet 1999, 5.

- ^ Kia 2011, 2.

- ^ أ ب Köprülü 1992, 110.

- ^ Fleet 1999, 6.

- ^ Eminov 1997, 27.

- ^ Kia 2011, 5.

- ^ http://www.moqatel.com/openshare/Behoth/Atrikia51/HokmOsmani/sec03.doc_cvt.htm

- ^ Quataert 2000, 24.

- ^ Levine 2010, 28.

- ^ Karpat 2004, 5–6.

- ^ Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons, ed. (2012). Century of Genocide. Routledge. pp. 118–124. ISBN 1135245509.

"By 1913 the advocates of liberalism had lost out to radicals in the party who promoted a program of forcible Turkification.

- ^ Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish national movement : its origins and development (1. ed. ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Univ. Press. p. 104. ISBN 081563093X.

With the crushing of opposition elements, the Young Turks simultaneously launched their program of forcible Turkification and the creation of a highly centralized administrative system."

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Levine 2010, 29.

- ^ Göcek 2011, 22.

- ^ Göcek 2011, 23.

- ^ أ ب Çaǧaptay 2006, 82.

- ^ أ ب Bosma, Lucassen & Oostindie 2012, 17

- ^ Çaǧaptay 2006, 84.

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/3596052?uid=2&uid=4&sid=21103809964991

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/280733?uid=2&uid=4&sid=21103809964991

- ^ http://books.google.com.eg/books?id=s_sMAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y

- ^ أ ب PMID 18161848 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ أ ب DOI:10.1086/316890

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand[2] - ^ DOI:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand[3] - ^ DOI:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057004308.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ أ ب DOI:10.1073/pnas.171305098

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ DOI:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.600201.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ DOI:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00043.x

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ DOI:10.1038/ejhg.2010.230

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ Cansu ÇAMLIBEL (24 December 2009). "Turks, Armenians share similar genes, say scientists". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/tu.html

- ^ Hatay 2007, 22.

- ^ Hatay 2007, 23.

- ^ "UNFICYP: United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus". United Nations.

- ^ http://www.moqatel.com/openshare/Behoth/Siasia2/SeraTurkGr/sec05.doc_cvt.htm

- ^ Federal Office of Statistics. "Population grouped according to ethnicity, by censuses 1961–1991". Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2011). "2011 Census (Final data)". National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. p. 4.

- ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria (2001). "2001 Census". National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria.

- ^ Novinite. "Scientists Raise Alarm over Apocalyptic Scenario for Bulgarian Ethnicity". Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_people#CITEREFClogg2002

- ^ Elsie 2010, 276.

- ^ Evans 2010, 11.

- ^ Statistical Office of Montenegro. "Population of Montenegro by sex, type of settlement, etnicity, religion and mother tongue, per municipalities" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "Turks in Montenegrin town not afraid to show identity anymore". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ Brozba 2010, 48.

- ^ http://www.google.com.eg/books?hl=ar&lr=&id=gDXbrQHGjbIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Whitman,+Lois+(1990),+Destroying+ethnic+identity:+the+Turks+of+Greece,+Human+Rights+Watch&ots=9LXoj4LWpj&sig=fIreZ8aixwUDnwnklVW8SM2ZGi4&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Whitman,%20Lois%20(1990),%20Destroying%20ethnic%20identity:%20the%20Turks%20of%20Greece,%20Human%20Rights%20Watch&f=false

- ^ Taylor 2004, 30.

- ^ أ ب Taylor 2004, 31.

- ^ Stansfield 2007, 70.

- ^ أ ب Jawhar 2010, 314.

- ^ International Crisis Group 2008, 16

- ^ Library of Congress, Iraq: Other Minorities, Library of Congress Country Studies, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+iq0033), retrieved on 24 November 2011

- ^ Yeni Asya. "Osmanlı devlet geleneği yaşatılıyor". Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Orhan 2010, 8.

- ^ أ ب Orhan 2010, 13.

- ^ Öztürkmen, Duman & Orhan 2011, 6.

- ^ Öztürkmen, Duman & Orhan 2011, 7.

- ^ Öztürkmen, Duman & Orhan 2011, 8.

- ^ Zaman. "Türk'ün Cezayir'deki lakabı: Hıyarunnas!". Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ أ ب Hizmetli 1953, 10.

- ^ Pan 1949, 103.

- ^ أ ب Home Affairs Committee 2011, Ev 34

- ^ Armin Laschet. "İngiltere'deki Türkler". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Necipoğlu, Gülru (1995). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 12. Leiden : E.J. Brill. p. 60. ISBN 9789004103146. OCLC 33228759. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Grabar, Oleg (1985). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 3. Leiden : E.J. Brill,. ISBN 9004076115. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Ibrahim Kaya (2004). Social Theory and Later Modernities: The Turkish Experience. Liverpool University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-85323-898-0. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ "Pamuk wins Nobel Literature prize". BBC. 12 October 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ Martin Dunford; Terry Richardson (3 June 2013). The Rough Guide to Turkey. Rough Guides. pp. 647–. ISBN 978-1-4093-4005-8. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ http://books.google.com.eg/books?id=dPAPeby7JTgC&pg=PA647&redir_esc=y

- ^ Laschet, Armin (17 September 2011). "İngiltere'deki Türkler". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Akben, Gözde (11 February 2010). "Olmalı mı Olmamalı mı?". Star Kıbrıs. Archived from the original on 13 April 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cemal, Akay (2 June 2011). "Dıştaki gençlerin askerlik sorunu çözülmedikçe…". Kıbrıs Gazetesi. Archived from the original on 1 August 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ U.S. Census Bureau: American FactFinder. "2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ Karpat 2004, 627.

- ^ The Sophia Echo. "Turkish Bulgarians fastest-growing group of immigrants in The Netherlands". Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ^ Hatay 2007, 40.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex Australia". Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Old foes, new friends". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 April 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ Presidency of the Republic of Turkey (2010). "Turkey-Australia: "From Çanakkale to a Great Friendship". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ^ OECD (2009). "International Questionnaire: Migrant Education Policies in Response to Longstanding Diversity: TURKEY" (PDF). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. p. 3.

- ^ TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs. "Briefing Notes on the Cyprus Issue". Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Kibris Gazetesi. "Avustralya'daki Kıbrıslı Türkler ve Temsilcilik..." Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ^ BRT. "AVUSTURALYA'DA KIBRS TÜRKÜNÜN SESİ". Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ Star Kıbrıs. "Sözünüzü Tutun". Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. "2006 Census Ethnic Media Package". Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Clogg 2002, 84.

- ^ MigrantsInGreece. "Data on immigrants in Greece, from Census 2001, Legalization applications 1998, and valid Residence Permits, 2004" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2009.[dead link]

- ^ The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. "Population by ethnic groups". Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Агентство РК по статистике. "ПЕРЕПИСЬ НАСЕЛЕНИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ КАЗАХСТАН 2009 ГОДА" (PDF). p. 10. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. "Population and Housing Census 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Демоскоп Weekly. "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г. Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации". Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ State statistics committee of Ukraine - National composition of population, 2001 census (Ukrainian)

- ^ Демоскоп Weekly. "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Aydıngün et al. 2006, 1.

- ^ Khazanov 1995, 202.

- ^ Babak, Vaisman & Wasserman 2004, 253.

- ^ Helton, Arthur C. (1998). "Meskhetian Turks: Solutions and Human Security". Open Society Institute. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

{{cite news}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Laczko, Stacher & von Koppenfels 2002, 187.

- ^ Steven A. Glazer (2011-03-22). "Turkey: Country Studies". Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ L. Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza; Paolo, Menozzi; Alberto, Piazza (1994). The history and geography of human genes. Princeton University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

المراجع

- Abadan-Unat, Nermin (2011), Turks in Europe: From Guest Worker to Transnational Citizen, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-84545-425-1.

- Abazov, Rafis (2009), Culture and Customs of Turkey, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0313342156.

- Akar, Metin (1993), "Fas Arapçasında Osmanlı Türkçesinden Alınmış Kelimeler", Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi 7: 91-110

- Abrahams, Fred (1996), A Threat to "Stability": Human Rights Violations in Macedonia, Human Rights Watch, ISBN 1-56432-170-3.

- Ágoston, Gábor (2010), "Introduction", in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan, Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 1438110251.

- Akar, Metin (1993), "Fas Arapçasında Osmanlı Türkçesinden Alınmış Kelimeler", Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi 7: 91–110

- Akgündüz, Ahmet (2008), Labour migration from Turkey to Western Europe, 1960–1974: A multidisciplinary analysis, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-7390-1.

- Aydıngün, Ayşegül; Harding, Çiğdem Balım; Hoover, Matthew; Kuznetsov, Igor; Swerdlow, Steve (2006), Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture, and Resettelment Experiences, Center for Applied Linguistics, http://calstore.cal.org/store/p-200-meskhetian-turks-an-introduction-to-their-history-culture-and-resettlement-experiences.aspx

- Babak, Vladimir; Vaisman, Demian; Wasserman, Aryeh (2004), Political Organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: Sources and Documents, Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-4838-8.

- Baedeker, Karl (2000), Egypt, Elibron, ISBN 1402197055.

- Bainbridge, James (2009), Turkey, Lonely Planet, ISBN 174104927X.

- Baran, Zeyno (2010), Torn Country: Turkey Between Secularism and Islamism, Hoover Press, ISBN 0817911448.

- Bennigsen, Alexandre; Broxup, Marie (1983), The Islamic threat to the Soviet State, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0619-6.

- Bokova, Irena (2010), "Recontructions of Identities: Regional vs. National or Dynamics of Cultrual Relations", in Ruegg, François; Boscoboinik, Andrea, From Palermo to Penang: A Journey Into Political Anthropology, LIT Verlag Münster, ISBN 3643800622

- Bogle, Emory C. (1998), Islam: Origin and Belief, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292708629.

- Bosma, Ulbe; Lucassen, Jan; Oostindie, Gert (2012), "Introduction. Postcolonial Migrations and Identity Politics: Towards a Comparative Perspective", Postcolonial Migrants and Identity Politics: Europe, Russia, Japan and the United States in Comparison, Berghahn Books, ISBN 0857453270.

- Brendemoen, Bernt (2002), The Turkish Dialects of Trabzon: Analysis, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447045701.

- Brendemoen, Bernt (2006), "Ottoman or Iranian? An example of Turkic-Iranian language contact in East Anatolian dialects", in Johanson, Lars; Bulut, Christiane, Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447052767.

- Brizic, Katharina; Yağmur, Kutlay (2008), "Mapping linguistic diversity in an emigration and immigration context: Case studies on Turkey and Austria", in Barni, Monica; Extra, Guus (eds), Mapping Linguistic Diversity in Multicultural Contexts, Walter de Gruyter, p. 248, ISBN 3110207346.

- Brozba, Gabriela (2010), Between Reality and Myth: A Corpus-based Analysis of the Stereotypic Image of Some Romanian Ethnic Minorities, GRIN Verlag, ISBN 3-640-70386-3.

- Bruce, Anthony (2003), The Last Crusade. The Palestine Campaign in the First World War, John Murray, ISBN 0719565057.

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006), Islam, Secularism, and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0415384583.

- Çaǧaptay, Soner (2006b), "Passage to Turkishness: immigration and religion in modern Turkey", in Gülalp, Haldun, Citizenship And Ethnic Conflict: Challenging the Nation-state, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0415368979.

- Campbell, George L. (1998), Concise Compendium of the World's Languages, Psychology Press, ISBN 0415160499.

- Cassia, Paul Sant (2007), Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1845452283.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2005), History Of Middle East, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 8126904488.

- Cleland, Bilal (2001), "The History of Muslims in Australia", in Saeed, Abdullah; Akbarzadeh, Shahram, Muslim Communities in Australia, University of New South Wales, ISBN 0-86840-580-9.

- Clogg, Richard (2002), Minorities in Greece, Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-706-8.

- Constantin, Daniela L.; Goschin, Zizi; Dragusin, Mariana (2008), "Ethnic entrepreneurship as an integration factor in civil society and a gate to religious tolerance. A spotlight on Turkish entrepreneurs in Romania", Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 7 (20): 28–41

- Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1162-7.

- Darke, Diana (2011), Eastern Turkey, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 1841623393.

- Delibaşı, Melek (1994), "The Era of Yunus Emre and Turkish Humanism", Yunus Emre: Spiritual Experience and Culture, Università Gregoriana, ISBN 8876526749.

- Duiker, William J.; Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2012), World History, Cengage Learning, ISBN 1111831653.

- Elsie, Robert (2010), Historical Dictionary of Kosovo, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-7231-5.

- Eminov, Ali (1997), Turkish and other Muslim minorities in Bulgaria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-319-4.

- Ergener, Rashid; Ergener, Resit (2002), About Turkey: Geography, Economy, Politics, Religion, and Culture, Pilgrims Process, ISBN 0971060967.

- Evans, Thammy (2010), Macedonia, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 1-84162-297-4.

- Farkas, Evelyn N. (2003), Fractured States and U.S. Foreign Policy: Iraq, Ethiopia, and Bosnia in the 1990s, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 1403963738.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya (2005), Subjects Of The Sultan: Culture And Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1850437602.

- Findley, Carter V. (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195177266.

- Fleet, Kate (1999), European and Islamic Trade in the Early Ottoman State: The Merchants of Genoa and Turkey, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521642213.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2003), Turkish in Macedonia and Beyond: Studies in Contact, Typology and other Phenomena in the Balkans and the Caucasus, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447046406.

- Friedman, Victor A. (2006), "Western Rumelian Turkish in Macedonia and adjacent areas", in Boeschoten, Hendrik; Johanson, Lars, Turkic Languages in Contact, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3447052120.

- Gogolin, Ingrid (2002), Guide for the Development of Language Education Policies in Europe: From Linguistic Diversity to Plurilingual Education, Council of Europe, http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Linguistic/Source/GogolinEN.pdf.

- Göcek, Fatma Müge (2011), The Transformation of Turkey: Redefining State and Society from the Ottoman Empire to the Modern Era, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1848856113.

- Hatay, Mete (2007), Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking?, International Peace Research Institute, ISBN 978-82-7288-244-9, http://www.prio.no/Global/upload/Cyprus/Publications/Is%20the%20Turkish%20Cypriot%20Population%20Shrinking.pdf.

- Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E. L.; Walrath, Dana; McBride, Bunny (2010), Anthropology: The Human Challenge, Cengage Learning, ISBN 0-495-81084-3.

- Hizmetli, Sabri (1953), "Osmanlı Yönetimi Döneminde Tunus ve Cezayir’in Eğitim ve Kültür Tarihine Genel Bir Bakış", Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi 32 (0): 1–12, http://dergiler.ankara.edu.tr/dergiler/37/776/9921.pdf

- Hodoğlugil, Uğur; Mahley, Robert W. (2012), "Turkish Population Structure and Genetic Ancestry Reveal Relatedness among Eurasian Populations", Annals of Human Genetics (Blackwell Publishing) 76 (2): 128–141

- Home Affairs Committee (2011), Implications for the Justice and Home Affairs area of the accession of Turkey to the European Union, The Stationery Office, ISBN 0-215-56114-7, http://www.statewatch.org/news/2011/aug/eu-hasc-turkey-jha-report.pdf

- Hopkins, Liza (2011), "A Contested Identity: Resisting the Category Muslim-Australian", Immigrants & Minorities (Routledge) 29 (1): 110–131.

- Hüssein, Serkan (2007), Yesterday & Today: Turkish Cypriots of Australia, Serkan Hussein, ISBN 0-646-47783-8.

- İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2005), "Institutionalisation of Science in the Medreses of Pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Turkey", in Irzik, Gürol; Güzeldere, Güven, Turkish Studies in the History And Philosophy of Science, Springer, ISBN 140203332X.

- Ilican, Murat Erdal (2011), "Cypriots, Turkish", in Cole, Jeffrey, Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1598843028.

- International Business Publications (2004), Turkey Foreign Policy And Government Guide, International Business Publications, ISBN 0739762826.

- International Crisis Group (2008), Turkey and the Iraqi Kurds: Conflict or Cooperation?, Middle East Report N°81 –13 November 2008: International Crisis Group, http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/Middle%20East%20North%20Africa/Iraq%20Syria%20Lebanon/Iraq/81Turkey%20and%20Iraqi%20Kurds%20Conflict%20or%20Cooperation.ashx

- International Crisis Group (2010). "Cyprus: Bridging the Property Divide". International Crisis Group..

- Jawhar, Raber Tal’at (2010), "The Iraqi Turkmen Front", in Catusse, Myriam; Karam, Karam (eds.), Returning to Political Parties?, The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, pp. 313–328, ISBN 1-886604-75-4, http://ifpo.revues.org/1115.

- Johanson, Lars (2001), Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map, Stockholm: Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul, http://turkoloji.cu.edu.tr/DILBILIM/johanson_01.pdf

- Johanson, Lars (2011), "Multilingual states and empires in the history of Europe: the Ottoman Empire", in Kortmann, Bernd; Van Der Auwera, Johan (eds), The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide, Volume 2, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110220253

- Kaplan, Robert D. (2002), "Who Are the Turks?", in Villers, James, Travelers' Tales Turkey: True Stories, Travelers' Tales, ISBN 1885211821.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2000), "Historical Continuity and Identity Change or How to be Modern Muslim, Ottoman, and Turk", in Karpat, Kemal H., Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, ISBN 9004115625.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004), Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, ISBN 9004133224.

- Kasaba, Reşat (2008), The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62096-1.

- Kasaba, Reşat (2009), A Moveable Empire: Ottoman Nomads, Migrants, and Refugees, University of Washington Press, ISBN 0295989483.

- Kermeli, Eugenia (2010), "Byzantine Empire", in Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan, Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 1438110251.

- Khazanov, Anatoly Michailovich (1995), After the USSR: Ethnicity, Nationalism and Politics in the Commonwealth of Independent States, University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-14894-7.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2011), Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 0313064024.

- King Baudouin Foundation (2008), "Diaspora philanthropy – a growing trend", Turkish communities and the EU, King Baudouin Foundation, http://www.kbs-frb.be/uploadedFiles/KBS-FRB/18)_Website_static_Content/Enews/International_newsletter_7_(May_2008).pdf.

- Kirişci, Kemal (2006), "Migration and Turkey: the dynamics of state, society and politics", in Kasaba, Reşat (ed), The Cambridge History of Turkey: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521620961.

- Knowlton, MaryLee (2005), Macedonia, Marshall Cavendish, ISBN 0-7614-1854-7.

- Köprülü, Mehmet Fuat (1992), The Origins of the Ottoman Empire, SUNY Press, ISBN 0791408205.

- Kötter, I; Vonthein, R; Günaydin, I; Müller, C; Kanz, L; Zierhut, M; Stübiger, N (2003), "Behçet's Disease in Patients of German and Turkish Origin- A Comparative Study", in Zouboulis, Christos (ed.), Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, Volume 528, Springer, ISBN 0-306-47757-2.

- Kurbanov, Rafik Osman-Ogly; Kurbanov, Erjan Rafik-Ogly (1995), "Religion and Politics in the Caucasus", in Bourdeaux, Michael (ed), The Politics of Religion in Russia and the New States of Eurasia, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-357-1.

- Kushner, David. 1997. “Self-Perception and Identity in Contemporary Turkey.” Journal of Contemporary History 32:219-233.

- Laczko, Frank; Stacher, Irene; von Koppenfels, Amanda Klekowski (2002), New challenges for Migration Policy in Central and Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, p. 187, ISBN 906704153X.

- Leiser, Gary (2005), "Turks", in Meri, Josef W., Medieval Islamic Civilization, Routledge, ISBN 0415966906.

- Leveau, Remy; Hunter, Shireen T. (2002), "Islam in France", in Hunter, Shireen, Islam, Europe's Second Religion: The New Social, Cultural, and Political Landscape, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0275976092.

- Levine, Lynn A. (2010), Frommer's Turkey, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0470593660.

- Minahan, James (2002), Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32111-6.

- Meeker, M. E. 1971. “The Black Sea Turks: Some Aspects of Their Ethnic and Cultural Background.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 2:318-345.

- National Institute of Statistics (2002), Population by ethnic groups, regions, counties and areas, Romania - National Institute of Statistics, http://www.insse.ro/cms/files/RPL2002INS/vol5/tables/t16.pdf

- Oçak, Ahmet Yaçar (2012), "Islam in Asia Minor", in El Hareir, Idris; M'Baye, Ravane, Different Aspects of Islamic Culture: Vol.3: The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, ISBN 9231041533.

- Orhan, Oytun (2010), The Forgotten Turks: Turkmens of Lebanon, ORSAM, http://www.orsam.org.tr/en/enUploads/Article/Files/2010110_sayi11_eng_web.pdf.

- OSCE (2010), "Community Profile: Kosovo Turks", Kosovo Communities Profile, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, http://www.osce.org/kosovo/75450.

- Oxford Business Group (2008), The Report: Algeria 2008, Oxford Business Group, ISBN 1-902339-09-6.

- Özkaya, Abdi Noyan (2007), "Suriye Kürtleri: Siyasi Etkisizlik ve Suriye Devleti’nin Politikaları", Review of International Law and Politics 2 (8), http://www.usak.org.tr/dosyalar/dergi/IdZgitj2V2vbuyxGGkzJnS8yvQqpT5.pdf.

- Öztürkmen, Ali; Duman, Bilgay; Orhan, Oytun (2011), Suriye'de değişim ortaya çıkardığı toplum: Suriye Türkmenleri, ORSAM, http://www.orsam.org.tr/tr/raporgoster.aspx?ID=2856.

- Pan, Chia-Lin (1949), "The Population of Libya", Population Studies 3 (1): 100–125

- Park, Bill (2005), Turkey's policy towards northern Iraq: problems and perspectives, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-38297-1

- Phillips, David L. (2006), Losing Iraq: Inside the Postwar Reconstruction Fiasco, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-05681-4

- Phinnemore, David (2006), The EU and Romania: Accession and Beyond, The Federal Trust for Education & Research, ISBN 1-903403-78-2.

- Polian, Pavel (2004), Against Their will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR, Central European University Press, ISBN 963-9241-68-7.

- Quataert, Donald (2000), The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521633281.

- Republic of Macedonia State Statistical Office (2005), Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Macedonia, 2002, Republic of Macedonia – State Statistical Office, http://www.stat.gov.mk/pdf/kniga_13.pdf

- Romanian National Institute of Statistics (2011), Comunicat de presă privind rezultatele provizorii ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi Locuinţelor – 2011, Romania-National Institute of Statistics, http://www.recensamantromania.ro/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Comunicat_DATE_PROVIZORII_RPL_2011.pdf

- Ryazantsev, Sergey V. (2009), "Turkish Communities in the Russian Federation", International Journal on Multicultural Societies 11 (2): 155–173, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001886/188648e.pdf.

- Saeed, Abdullah (2003), Islam in Australia, Allen & Unwin, ISBN 1-86508-864-1.

- Saunders, John Joseph (1965), "The Turkish Irruption", A History of Medieval Islam, Routledge, ISBN 0415059143.

- Scarce, Jennifer M. (2003), Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East, Routledge, ISBN 0700715606.

- Seher, Cesur-Kılıçaslan; Terzioğlu, Günsel (2012), "Families Immigrating from Bulgaria to Turkey Since 1878", in Roth, Klaus; Hayden, Robert, Migration In, From, and to Southeastern Europe: Historical and Cultural Aspects, Volume 1, LIT Verlag Münster, ISBN 3643108958.

- Shaw, Stanford J. (1976), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey Volume 1 , Empire of the Gazis: The Rise and Decline of the Ottoman Empire 1280–1808, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521291631.

- Somel, Selçuk Akşin (2003), Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0810843323.

- Sosyal, Levent (2011), "Turks", in Cole, Jeffrey, Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1598843028.

- Stansfield, Gareth R. V. (2007), Iraq: People, History, Politics, Polity, ISBN 0-7456-3227-0.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (2000), The Balkans Since 1453, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1850655510.

- Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, Anthony (2010), "Turkic Peoples", Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 143812676X.

- Taylor, Scott (2004), Among the Others: Encounters with the Forgotten Turkmen of Iraq, Esprit de Corps Books, ISBN 1-895896-26-6.

- Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, Anthony (2010), "Turks: nationality", Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 143812676X.

- Tomlinson, Kathryn (2005), "Living Yesterday in Today and Tomorrow: Meskhetian Turks in Southern Russia", in Crossley, James G.; Karner, Christian (eds.), Writing History, Constructing Religion, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-5183-5.

- Turkish Embassy in Algeria (2008), Cezayir Ülke Raporu 2008, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.musavirlikler.gov.tr/altdetay.cfm?AltAlanID=368&dil=TR&ulke=DZ.

- Twigg, Stephen; Schaefer, Sarah; Austin, Greg; Parker, Kate (2005), Turks in Europe: Why are we afraid?, The Foreign Policy Centre, ISBN 1903558794, http://fpc.org.uk/fsblob/597.pdf

- UNHCR (1999), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Azerbaijan, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/pdfid/3ae6a6504.pdf.

- UNHCR (1999b), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Georgia, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/pdfid/3ae6a6590.pdf.

- Visintainer, Ermanno (2011), İtalya'da Unutulmuş Türk Varlığı: Moena Türkleri, ORSAM, http://www.orsam.org.tr/tr/trUploads/Yazilar/Dosyalar/201258_14raportum.pdf.

- Whitman, Lois (1990), Destroying ethnic identity: the Turks of Greece, Human Rights Watch, ISBN 0-929692-70-5.

- Wolf-Gazo, Ernest. (1996) "John Dewey in Turkey: An Educational Mission". Retrieved 6 March 2006.

- Yardumian, Aram; Schurr, Theodore G. (2011), "Who Are the Anatolian Turks? A Reappraisal of the Anthropological Genetic Evidence", Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia (M.E. Sharpe) 50 (1): 6–42

- Yiangou, Anastasia (2010), Cyprus in World War II: Politics and Conflict in the Eastern Mediterranean, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1848854366.

- Zeytinoğlu, Güneş N.; Bonnabeau, Richard F.; Eşkinat, Rana (2012), "Ethnopolitical Conflict in Turkey: Turkish Armenians: From Nationalism to Diaspora", in Landis, Dan; Albert, Rosita D., Handbook of Ethnic Conflict: International Perspectives, Springer, ISBN 1461404479.

وصلات خارجية

Media related to Turkish people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Turkish people at Wikimedia Commons

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Pages with incomplete DOI references

- CS1 errors: extra text: edition

- Pages with incomplete PMID references

- Articles with dead external links from October 2010

- CS1 errors: chapter ignored

- "Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- أتراك

- جماعات عرقية في أوروپا