سلطنة غلدي

سلطنة غلدي Saldanadda Geledi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| أواخر القرن 17–1911 | |||||||||

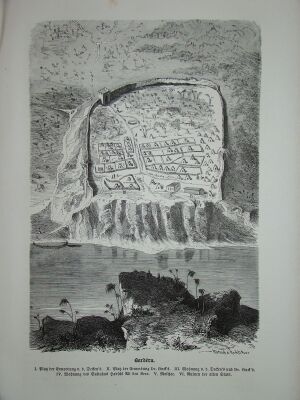

سلطنة غلدي والمناطق المجاورة عام 1914، في جنوب الصومال. | |||||||||

| العاصمة | أفجويي | ||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | الصومالية • العربية | ||||||||

| الدين | الإسلام السني | ||||||||

| الحكومة | سلطنة | ||||||||

| السلطان الإمام الشيخ | |||||||||

• أواخر القرن 17 - منتصف القرن 18 | إبراهيم أدير | ||||||||

• 1878 – 1911 | عثمان أحمد | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• تأسست | أواخر القرن 17 | ||||||||

• انحلت | 1911 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

سلطنة غلدي (صومالية: Saldanadda Geledi، إنگليزية: Sultanate of the Geledi، تُعرف أيضاً باسم أسرة غبرون)، [1] هي مملكة صومالية حكمت أجزاء من القرن الأفريقي في أواخر القرن 17-القرن 19. كانت السلطنة تحت حكم أسرة غبرون. أسسها الجندي الغلدي إبراهيم أدير، الذي هزم مختلف مقاطع سلطنة أجوران ونصب الغربون على رأس السلطة السياسية. بعد توحيد محمود إبراهيم، وصلت الأسرة ذروتها تحت حكم يوسف محمود إبراهيم، الذي نجح في تحديث اقتصاد الغلدي والقضاء على التهديدات الإقليمية مع فتح باردرا عام 1843،[2] and would go on to receive tribute from Said bin Sultan the ruler of the Omani Empire.[3] كان لسلاطين غلدي علاقات إقليمية قوية وأقاموا تحالفات مع سلطنتي بات وويتو على الساحل الأفريقي.[4] احتفظت التجارة وسلطة گلدي بقوتهما حتى وفاة السلطان الشهير أحمد يوسف عام 1878. دُمجت السلطنة في النهاية في أرض الصومال الإيطالي عام 1911.[5]

الأصول

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ الصومال |

|

|

في نهاية القرن السابع عشر، كانت سلطنة أجوران تتدهو، وتحررت العديد من الدويلات التابعين أو تم استيعابهم من قبل قوى صومالية جديدة. كانت إحدى هذه القوى هي سلطنة سيليس، التي بدأت في ترسيخ حكمها على منطقة أفجويي. قاد إبراهيم أدير قاد الثورة ضد حاكم سيليس عمر أبرون وابنته الأميرة فاي.[6] بعد انتصاره على سيلسيس، أعلن إبراهيم نفسه سلطاناً وأسس "أسرة غبرون".

كانت سلطنة غلدي مملكة رحنوينية يحكمها نبيل غلدي كان له نفوذ على نهري جوبا وشبيلي في الداخل وعلى ساحل بنادير. كان لدى سلطنة غلدي ما يكفي من القوة لإجبار العرب الجنوبيين على دفع الجزية.[7]

يدعي نبلاء غلدي أن ينسبهم يمتد إلى عمر الدين، الذي كان لديه 3 أشقاء آخرين، فخر واثنين آخرين أسماءهم مختلفة مثل شمس وعمودي والهي وأحمد. عُرفوا معًا باسم "أفارتا تيميد"، "الأربعة الذين أتوا"، مما يشير إلى أصولهم من شبه الجزيرة العربية. كانت مزاعم النسب الممتد لشبه الجزيرة العربية لأسباب تتعلق بالشرعية بشكل رئيسي.[8]

البيروقراطية

مارست سلطنة غلدي سلطة مركزية قوية خلال وجودها وتمتلك جميع المؤسسات والرفاهية لدولة حديثة متكاملة: تسيير البيروقراطية، والنبالة الوراثية، والألقاب الأرستقراطية، ونظام الضرائب، والاهتمام بالسياسة الخارجية، كما كان لها علم دولة وجيش نظامي.[9][10] كما حافظة السلطنة العظيمة على سجلات مكتوبة لأنشطتها التي لا تزال موجودة في المتاحف.[11]

كانت عاصمة سلطنة غدي في أفجويي حيث أقام الحكام. كان لدى المملكة عددًا من القلاع-الحصون مع مجموعة متنوعة من البنى المختلفة في مناطق مختلفة داخل السلطنة، بما في ذلك قلعة في لوك وقلعة في بارديرا.[12]

في ذروتها، حكمت السلطنة جميع أراضي ديجل وميرفيل داخل الصومال الحالية. هذا ما يشير إليه البعض باسم الكونفدرالية الغلدية. لم تقتصر الكونفدرالية على ديجل وميرفيل فحسب، بل شملت القبائلة الصومالية الأخرى مثل Bimaal، shekhaal، وWacdaan. لتكوين مثل هذا السلطنة المتنوعة، روج الحكام سياسة الإدارة غير المباشرة والمرنة. لقد سمحوا لزعماء القبائل، والأئمة، والشيوخ، والأخيار بلعب أدوار هامة في إدارة السلطنة. لم يكن حكام غلدي الرؤساء السياسيون للسلطنة فحسب، بل يعتبرون أيضًا الزعماء الدينيين.[13] كان الأخيار شيوخًا يوفقون ويحلون حالات مثل جرائم القتل ويتلون الفاتحة بعد الحكم. إذا وقعت مظلمة بين مجموعتين عرقيتين مختلفين، يُعقد "الجوجول" (جلسة) بين أخيار كلا المجموعتين.[14]

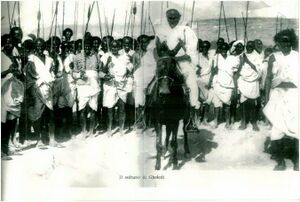

كان للسلطان حراساً نظاميين يتكونون من عبيد مسلحين لحمايته ممن يتمنون له الأذى. كما كان له وسطاء بينه وبين عشائر الغلدي الفرعية والذين يتلقون توجيهاته وقراراته في مختلف الأمور.[15] كانت العمة هي رمز سلطة السلطان. كان يضعها على رأسه كبار شيوخ نسل الأبيكارو.[16][1]

Clear devolution of power was also present within the politics of the Geledi Sultan delegating certain regions of the sultanate to be managed by close relatives, who wielded significant influence in their own right. Sultan Ahmed Yusuf's administration was described as such by the British Parliament.

The Somali tribe of Ruhwaina. The Chief of this and other tribes behind Brava, Marka and Mogdisho is Ahmed Yusuf, who resides at Galhed, one day's march or less from the latter town. Two days further inland is Dafert, a large town governed by Aweka Haji, his brother. These are the principal towns of the Ruhwaina. At four, five, and six hours respectively from Marka lie the towns of Golveen (Golweyn), Bulo Mareerta, and Addormo, governed by Abobokur Yusuf, another brother who though nominally under the orders of the first-named chief, levies black-mail on his own account, and negotiates with the governors of Marka and Brava direct. He resides with about 2,000 soldiers principally slaves at Bulo Mareta; the towns of Gulveen which he often visits and Addormo being occupied by somalis growing produce, cattle &c. and doing a large trade with Marka.[17] The brother of Sultan Ahmed Yusuf, Abobokur Yusuf managed the lands opposite the Banadir ports of Brava & Marka and also received a tribute from Brava. This Abobokur Yusuf was accustomed to send messengers to Brava for tribute, and he drew thence about 2,000 dollars per annum.[17]

During the Scramble for Africa period between the 1880s and the first World War, Geledi was bounded to the north by the Huwan Region, the Huwan later forming a semi-independent vassal state of Abyssinia, to the east by Hobyo Sultanate and Italian leasing of Benadir, and to the south by the British East Africa Protectorate.[18][أ]

الاقتصاد

The Geledi Sultanate maintained a vast trading network, and had trade relations with Arabia, Persia, India, Near East, Europe and the Swahili coast, dominating the East African trade, and minting its own currency, and were recognized as a powerful regional power.[19]

In the case of the Geledi, wealth accrued to the nobles and to the Sultanate, not only from the market cultivation which it had utilized from the Shebelle and Jubba valleys, but also trade from their involvement in the slave trade and other enterprises such as ivory, cotton, iron, gold, and among many other commodities. Generally, they also raised livestock animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, and chickens.[20]

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Gobroon dynasty had turned their religious prestige into formidable political power and were recognized as the rulers of an increasingly centralized and wealthy state. As already mentioned, much of their wealth was based on control over the fertile riverine lands. Using slave labour obtained through the coastal ports, the Geledi gradually shifted their economic base away from its traditional dependency on pastoralism and subsistence agriculture to one built largely on plantation agriculture and production of cash crops such as grain, cotton, maize, sorghum, and a variety of fruits and vegetables, especially bananas, mangos, sugarcane, cotton, tomatoes, squash and much more. The region is traversed by historic caravan routes. Trade on the rivers themselves connected with the coast to the interior markets.[21] During this period, the Somali agricultural output to Arabian markets was so great that the coast of South Somalia came to be known as the Grain Coast of Yemen and Oman.[22]

Afgooye, the headquarters of the Sultanate, was an extremely wealthy and large city. Afgooye had some thriving industries such as weaving, shoemaking, tableware, jewellery, pottery and produced various products. Afgooye was the crossroads of caravans bringing ostrich feathers, leopard skins, and aloe in exchange for foreign fabrics, sugar, dates and firearms. They raised numerous livestock animals for meat, milk and ghee. The farmers of Afgooye produced large quantity of fruits and vegetables.[23]

Afgooye merchants would boast of their wealth; one of their wealthiest said

Moordiinle iyo mereeyey iyo mooro lidow, maalki jeri keenow kuma moogi malabside. Bring all the wealth of Moordiinle, Mereeyey, and the enclosures of lidow, I scarcely notice it.[23]

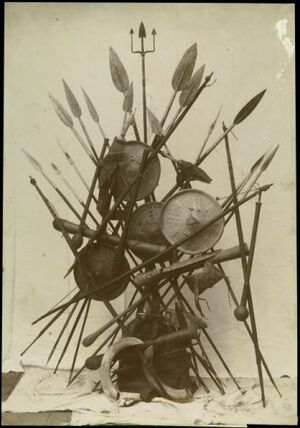

العسكرية

The Geledi army numbered around 20,000 men in times of peace, with a maximum of 50,000 troops in times of war.[24] The supreme commanders of the army were the Sultan and his brother, who in turn had Malaakhs and Garads under them. The military was supplied with rifles and cannons by Somali traders of the coastal regions that controlled the East African arms trade.

The best horse breeds were raised in Luuq and later sent to the army after maturity. They would be used mainly for military purposes, and numerous stone fortifications were erected to provide shelter for the army in the interior and coastal districts. In each province, the soldiers were under the supervision of a military commander known as a Malaakh, and the coastal areas and the Indian Ocean trade were protected by a powerful navy.[25]

المجتمع

The Geledi society is divided into three segments; nobles, commoners, and slaves (to use terms adopted by Helander) Each of these castes consist of several lineage groups whose federation formed the Geledi state; the lineages are divided between two moieties. Tolweyne and Yebdaale, each living in its section of the city. The nobles, in the old society, were the ruling group but depended on the support of the commoner lineages.[26]

النبالة

The noble section of the society belonged to rulers. However, all members of the Geledi clan were also considered to be of noble stock despite the majority of them not being rulers. Nobility was not only exclusive to the Geledi clan as there were rulers of many districts in the Geledi realm that didn't belong to the Geledi lineage.[26]

العوام

The commoners were typical citizens that mainly consist of non-Geledi Somalis and traditionally consist of urban dwellers, farmers, pastoral nomads as well as officials, merchants, engineers, scholars, soldiers, craftsmen, port workers, and other various professions. The commoners were the majority in the kingdom and were treated as equals.[26]

العبيد

The slaves were mostly of Bantu origin and were used for labour. The men would work as agricultural labourers led by their farmer-owners and some would work in construction led by engineers. They would also be employed into the army and were separated from the rest of the Geledi army and were branched as Mamaluks meaning slave soldiers. The women would work as domestic servants and perform a variety of household services for their owners, from providing, cooking, cleaning, and laundry, taking care of children and elderly dependents, and other household errands. They would also be looked down upon for any kind of sexual contact and were deemed as unattractive.[27]

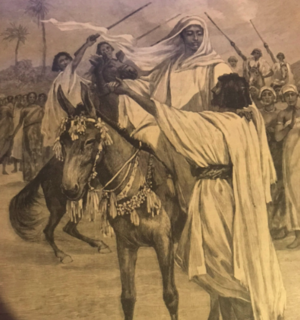

The Bantus were not exclusive to slavery. Oromos would sometimes be enslaved following raids and wars.[28] However, there were marked differences in terms of the perception, capture, treatment, and duties of the Oromo versus the Bantu slaves. On an individual basis, Oromo subjects were not viewed as racially inferior by their Somali captors.[29] Despite Oromos taking the same roles as the Bantus, they were not treated the same. The most fortunate of the men worked as the officials or bodyguards of the ruler and emirs, or as business managers for rich merchants. They enjoyed significant personal freedom and occasionally held slaves of their own.[30] Prized for their beauty and viewed as legitimate sexual partners, many Oromo women became either wives or concubines of their Somali owners, while others became domestic servants. The most beautiful ones often enjoyed a wealthy lifestyle and became mistresses of the elite or even mothers to rulers.[31]

الحكام

حكام سلطنة غلدي

| # | السلطان | الحكم | ملاحظات |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | إبراهيم أدير | late 17th century–mid 18th century | Founded the Geledi Sultanate after defeating the Ajuran Sultanate. First ruler in the Gobroon Dynasty.[32] |

| 2 | محمد إبراهيم | mid-18th-1828[33] | Consolidated Goobron power, incorporated the Murusade as allies and ended the Silcis threat.[14] |

| 3 | يوسف محمود إبراهيم | 1828–1848[33] | Rule marked the start of the golden age of the Geledis. Destroyed the Bardhera Jama'a and revolutionized the Geledi economy. Collected tribute from Said bin Sultan ruler of the Omani Empire[3] |

| 4 | Ahmed Yusuf | 1848–1878[33] | Defended the Banadir coast from incursion and reestablished Gobroon power after his father's defeat in 1848[34] |

| 5 | Osman Ahmed | 1878-1910[33] | Inherited throne from father. Reign marked the end of the Geledi Sultanate. Decisively defeated the Abyssinians at the Battle of Luuq and the Dervish at the Battle of Hudur. |

الذكرى

The Sultanate left a rich legacy behind which continues to live on in popular memory and poetry composed about the powerful Sultans and other noble figures during the period. One notable poem was recorded by Virginia Luling in 1989 during her visit to Afgooye. Geledi laashins (poets) sang about the ever present issue of land theft by the Somali government. Sultan Subuge was asked to help the community and was reminded of his legendary Gobroon forefathers of the centuries prior.[35]

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

المصادر

- ^ أ ب Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 229

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. xxix. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ أ ب Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History, Volume 2. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 990. ISBN 9781579584542.

- ^ Marguerite, Ylvisaker (1978). "The Origins and Development of the Witu Sultanate". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 11 (4): 669–688. doi:10.2307/217198. JSTOR 217198.

- ^ The social structure of southern Somali tribes, Virginia Luling, pg. 204

- ^ Luling (1993), p.13.

- ^ Luling (2002), p.272.

- ^ Luling, Virginia (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years (in الإنجليزية). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-874209-98-0.

- ^ Horn of Africa, Volume 15, Issues 1-4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.

- ^ Michigan State University. African Studies Center, Northeast African studies, Volumes 11-12, (Michigan State University Press: 1989), p.32.

- ^ Sub-Saharan Africa Report, Issues 57-67. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1986. p. 34.

- ^ S. B. Miles, On the Neighbourhood of Bunder Marayah, Vol. 42, (Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the institute of British Geographers): 1872), p.61-63.

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 210. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ أ ب The social structure of southern Somali tribes, Virginia Luling, pg. 179

- ^ The social structure of southern Somali tribes, Virginia Luling, pg. 190

- ^ The social structure of southern Somali tribes, Virginia Luling, pg. 191

- ^ أ ب Great Britain, House of Commons (1876). Accounts and Papers volume 70. HM Stationery Office. p. 13.

- ^ Rayidow, poem 80 ; Diiwaanka gabayadii, 1856-1921, "Huwan oo dadkii Mililiq iyo amxaaro raacay ahaa, Adarina laga maamulayey"

- ^ Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 155

- ^ Nelson, Harold (1982). "The Society and its Environment". Somalia, a Country Study. ISBN 9780844407753.

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 116. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- ^ East Africa and the Indian Ocean By Edward A. Alpers pg 66

- ^ أ ب Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 28. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- ^ Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society ..by Bombay Geographical Society pg.392

- ^ Reese, Scott Steven (1996). Patricians of the Benaadir: Islamic learning, commerce and Somali urban identity in the nineteenth century. University of Pennsylvania. p. 179.

- ^ أ ب ت Lewis, I.M (1996). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 221. ISBN 9781135751746.

- ^ Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1746

- ^ Bridget Anderson, World Directory of Minorities, (Minority Rights Group International: 1997), p. 456.

- ^ Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 116.

- ^ Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 82.

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (2004). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0203493021.

- ^ Njoku, Raphael (2013). The History of Somalia (in الإنجليزية). Greenwood. ISBN 9780313378577.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. p. 26. ISBN 9780810866041. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ United Kingdom House of Commons (1968). Irish University Press Series of British Parliamentary Papers: Slave trade. Irish University Press. p. 475.

- ^ Luling, Virginia (1996). "'The Law Then Was Not This Law': Past and Present in Extemporized Verse at a Southern Somali Festival". African Languages and Cultures. Supplement. No. 3 (3): 213–228. JSTOR 586663.

قراءات إضافية

- Luling, Virginia (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0914-1.

- Luling, Virginia (1993). The Use of the Past: Variation in Historical traditions in a South Somalia community. University of Besançon.

- Virginia Luling (2002). Somali Sultanate: the Geledi city-state over 150 years. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0914-1.

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing صومالية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- سلطنة أجوران

- امبراطوريات سابقة

- بلدان سابقة في أفريقيا

- امبراطوريات صومالية

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1911

- التاريخ الحديث المبكر للصومال

- التاريخ الحديث للصومال

- بلدان سابقة