بحر النرويج

| بحر النرويج Norwegian Sea | |

|---|---|

ڤستفيوردن مع جبال أرخبيل لوفوتن تبدو من جزيرة لوڤوي في ستايگن. ڤاگاكايلن (942 م) هو أعلى القمتين في منتصف الصورة. | |

بحر النرويج يحده بالخط الأحمر (Europäisches Nordmeer بالألمانية) | |

| الموقع | شمال أوروپا |

| الإحداثيات | 69°N 2°E / 69°N 2°E |

| Type | بحر |

| الموارد الرئيسية |

|

| بلدان الحوض | النرويج، آيسلندا والدنمارك (جزيرة فارو) والمملكة المتحدة (جزر شتلاند) |

| المراجع | [1][2][3] |

بحر النرويج (نرويجية: Norskehavet، Norwegian Sea)، هو بحر هامشي في المحيط الأطلسي الشمالي، شمال غرب النرويج. يقع بحر النرويج بين بحر الشمال وبحر گرينلاند ويجاور المحيط الأطلسي الشمالي من الغرب وبحر بارنتس من الشمال الشرقي. في الجنوب الغربي، يفصله عن المحيط الأطلسي حافة غاطسة تمتد بين آيسلندا وجزر فارو. إلى الشمال، تفصله حافة يان ماين عن بحر گرينلاند.

على عكس العديد من البحار الأخرى ، فإن معظم قاع البحر النرويجي ليس جزءًا من الجرف القاري وبالتالي يقع على عمق كبير يبلغ حوالي كيلومترين في المتوسط. تم العثور على رواسب غنية من النفط والغاز الطبيعي تحت قاع البحر ويتم استكشافها تجارياً، في المناطق التي يصل عمق البحر فيها إلى حوالي كيلومتر واحد. المناطق الساحلية غنية بالأسماك التي تزور البحر النرويجي من شمال الأطلسي أو من بحر بارنتس (القد) لوضع البيض. يضمن تيار شمال الأطلسي الدافئ درجات حرارة عالية ومستقرة نسبيًا للمياه ، لذلك على عكس بحار القطب الشمالي، يكون البحر النرويجي خاليًا من الجليد طوال العام. خلصت الأبحاث الحديثة إلى أن الحجم الكبير للمياه في البحر النرويجي مع قدرته الكبيرة على امتصاص الحرارة أكثر أهمية كمصدر للشتاء المعتدل في النرويج من تيار الخليج وامتداداته.[4]

الامتداد

تـُعرِف المنظمة الهيدروغرافية الدولية حدود بحر النرويج كما يلي:[5]

- من الشمال الشرقي. الخط الواصل من نقطة أقصى جنوب غرب سپتسبرگن إلى رأس الشمال في جزيرة الدب، عبر تلك الجزيرة إلى رأس الثور ومنها إلى رأس الشمال في النرويج (25°45'E).

- من الجنوب الشرقي. الساحل الغربي للنرويج بين رأس الشمال ورأس ستات (62°10′N 5°00′E / 62.167°N 5.000°E).

- من الجنوب. From a point على الساحل الغربي للنرويج في Latitude 61°00' North بحذى خط الطول إلى Longitude 0°53' West ثم خط إلى الطرف الشمالي الشرقي لـ Fuglö (62°21′N 6°15′W / 62.350°N 6.250°W) ويواصل إلى الطرف الشرقي لـ گرپير (65°05′N 13°30′W / 65.083°N 13.500°W) في آيسلندا.

- من الغرب. الحد الجنوبي الشرقي لبحر گرينلاند [خط واصل بين أقصى النقاط بجنوب غرب سپتسبرگن إلى النقطة الشمالية على جزيرة يان ماين، نزولاً على الساحل الغربي للجزيرة إلى أقصى جنوبها، ثم الخط الواصل إلى الطرف الشرقي لـ گرپير (65°05′N 13°30′W / 65.083°N 13.500°W) في آيسلندا].

التكوين والجغرافيا

تكون بحر النرويج تكون قبل حوالي 250 ميلون سنة، عندما الصفيحة الأوراسية في النرويج وصفيحة أمريكا الشمالية (وتشمل گرينلاند)، بدأتا بالتحرك عن بعضهما البعض. الصفيحة الموجودة بين النرويج وگرينلاند بدأت تصبح أعمق وأعرض.[6] انحدار الصفيحة الحالي في بحر النرويج يُحدد الحدود بين النرويج وگرينلاند، كما كانت تقريبا قبل 250 مليون سنة. في الشمال إنه يمتد إلى الشرق من سڤالبارد وفي الجنوب الغربي بين بريطانيا وفارو. هذا الانحدار الصحيفي يحتوي على أراضي غنية بالسمك والعديد من الشعب المرجانية. التوقف في التحرك بعد الانفصال في القارات سبب انهيارات ترابية، مثل انهيار ستوريگا قبل 8 ألف سنة الذي سبب تسونامي كبير.[6]

سواحل بحر النرويج تشكلت خلال العصر الجليدي. لذلك المثلجات الكبيرة التي كان يبلغ طولها عدة كيلومترات دُفعت إلى الأرض مُكونة خللات، مُزيلة القشرة إلى البحر ما سبب تمديد طول لساحل. يمكن رؤية ذلك بشكل واضح عند هيلجلند وشمال جزر لوفوتن.[6] الجرف النرويجي القاري عرضه بين 40 و200 كيلومتر، ويمتلك شكل غير عن الجروف في بحر الشمال وبحر بارنتس. يحتوي على العديد من الخنادق والقمم الغير منظمة التي في العادة تملك سعة أقل من 100 متر، ولكنها يمكن أن تصل إلى 400. إنهم مُغطون بخليط من الحصى، الرمال، والطين، والخنادق تُستخدم من قبل السمك كأرض لوضع البيض.[6] أعمق في البحر هناك خندقان عميقان مفصولان من قبل سلسلة تلل منخفضة (أقل نقطة 3,000 متر) بين هضبة ڤورنگ وجزيرة يان ماين. الحوض الجنوبي أكبر وأعمق، مع مساحة تبلغ 3,500 وعمق يبلغ 4,000 متر. الحوض الشمالي أضحل حيث يبلغ عمقه من 3,200 إلى 3,300، ولكنه يحتوي على العديد من الواقع الانفرادية التي تصل إلى 3,500 متر. العتبات الغواضة والمنحدرات القارية يُشكلون حدود الأحواض الثلاثة مع البحار المتصلة. في الجنوب يقع الجرف القاري الأوروبي وبحر الشمال، إلى الشرق الجرف القاري الأوراسية مع بحر بارنتس. إلى الغرب سلسلة اسكتلندا-گرينلاند تفصل بحر النرويج عن المحيط الأطلسي. السلسلة في العادة تبلغ عمق 500 متر، فقد في بعض الأحيان تبلغ 850 متر. في الشمال تقع سلسلة يان ماين وسلسلة مونز، مع عمق 2000 متر في بعض المناطق يبلغ العمق 2600 متر.

الهيدروگرافيا

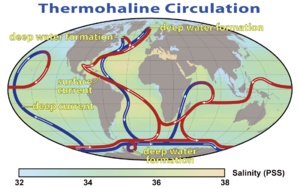

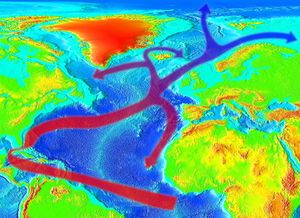

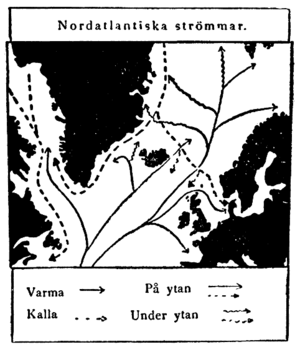

ثمة أربع كتل مائية رئيسية ناشئة من المحيطين الأطلسي والقطبي تلتقي في بحر النرويج، وتعتبر التيارات المرتبطة بها ذات أهمية أساسية بالنسبة للمناخ العالمي. يتدفق تيار شمال الأطلسي الدافئ المالح من المحيط الأطلسي، بينما ينشأ التيار النرويجي الأبرد والأقل ملوحة في بحر الشمال. ينقل ما يسمى بتيار شرق أيسلندا المياه الباردة جنوبا من البحر النرويجي باتجاه أيسلندا ثم شرقا على طول الدائرة القطبية الشمالية؛ يحدث هذا التيار في طبقة الماء الوسطى. وتتدفق المياه العميقة إلى البحر النرويجي من بحر گرينلاند.[7] المد والجزر في البحر هو نصف يومي، أي يحدث مرتين في اليوم، بارتفاع يصل 3.3 متر.[1]

التيارات السطحية

التيارات العميقة

The Norwegian Sea is connected with the Greenland Sea and the Arctic Ocean by the 2,600-metre deep Fram Strait.[8] The Norwegian Sea Deep Water (NSDW) occurs at depths exceeding 2,000 metres; this homogeneous layer with a salinity of 34.91‰ experiences little exchange with the adjacent seas. Its temperature is below 0 °C and drops to −1 °C at the ocean floor.[7] Compared with the deep waters of the surrounding seas, NSDW has more nutrients but less oxygen and is relatively old.[9]

The weak deep-water exchange with the Atlantic Ocean is due to the small depth of the relatively flat Greenland-Scotland Ridge between Scotland and Greenland, an offshoot of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Only four areas of the Greenland-Scotland Ridge are deeper than 500 metres: the Faroe-Bank Channel (about 850 metres), some parts of the Iceland-Faroe Ridge (about 600 metres), the Wyville-Thomson Ridge (620 metres), and areas between Greenland and the Denmark Strait (850 metres) – this is much shallower than the Norwegian Sea.[10][9] Cold deep water flows into the Atlantic through various channels: about 1.9 Sv through the Faroe Bank channel, 1.1 Sv through the Iceland-Faroe channel, and 0.1 Sv via the Wyville-Thomson Ridge.[11] The turbulence that occurs when the deep water falls behind the Greenland-Scotland Ridge into the deep Atlantic basin mixes the adjacent water layers and forms the North Atlantic Deep Water, one of two major deep-sea currents providing the deep ocean with oxygen.[12]

المناخ

الدوران الحراري يلعب دور في مناخ بحر النرويج، ويحيد متوسط المناخ الإقليمي. هناك أيضا اختلاف يُعادل 10 درجات بين البحر والساحل. الحرارة ارتفعت بين 1920 و1960 كا سبب ارتفاع عدد العواصف في تلك الفترة. العواصف كثرت بين 1880 و1910 وقُلت بين 1910 و1960، بعد ذلك عدت إلى المستويات العادية.

يختلف بحر النرويج عن بحر گرينلاند والبحار المجاورة في الشمال أنه لا يتجمد، بسبب التيرات الدافئة. الحمل الحراري بين المياه الدافئة نسبيا والهواء البارد في الشتاء يلعب دور مهم في مناخ القطب الشمالي. خط تساوي درجات الحرارة (آيزوثرم) العشر درجات في يوليو (درجة حرارة الهواء) يمر عبر الحدود الشمالية لبحر النرويج وغالبا ما يُعتبر الحد الجنوبي للقطب الشمالي. شتاء بحر النرويج يمتلك أدنى ضغط جوي في إقليم القطب الشمالي حيث معظم الإنخفضات الآيسلندية تتكون. حرارة المياه في معظم مناطق البحر تبلغ من 2 إلى 7°س في فبراير ومن 8 إلى 12°س في أغسطس.[13]

الحياة النباتية والحيوانية

The Norwegian Sea is a transition zone between boreal and Arctic conditions, and thus contains flora and fauna characteristic of both climatic regions.[7] The southern limit of many Arctic species runs through the North Cape, Iceland, and the center of the Norwegian Sea, while the northern limit of boreal species lies near the borders of the Greenland Sea with the Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea; that is, these areas overlap. Some species like the scallop Chlamys islandica and capelin tend to occupy this area between the Atlantic and Arctic oceans.[14]

الطحالب وعضيات قاع البحر

Most of the aquatic life in the Norwegian Sea is concentrated in the upper layers. Estimates for the entire North Atlantic are that only 2% of biomass is produced at depths below 1,000 metres and only 1.2% occurs near the sea floor.[15]

The blooming of the phytoplankton is dominated by chlorophyll and peaks around 20 May. The major phytoplankton forms are diatoms, in particular the genus Thalassiosira and Chaetoceros. After the spring bloom the haptophytes of the genus Phaecocystis pouchetti become dominant.[16]

Shrimp Pandalus borealis

الأسماك

Capelin is a common fish of the Atlantic-arctic transitional waters |

The Norwegian coastal waters are the most important spawning ground of the herring populations of the North Atlantic, and the hatching occurs in March. The eggs float to the surface and are washed off the coast by the northward current. Whereas a small herring population remains in the fjords and along the northern Norwegian coast, the majority spends the summer in the Barents Sea, where it feeds on the rich plankton. Upon reaching puberty, herring returns to the Norwegian Sea.[17] The herring stock varies greatly between years. It increased in the 1920s owing to the milder climate and then collapsed in the following decades until 1970; the decrease was, however, at least partly caused by overfishing.[18] The biomass of young hatched herring declined from 11 million tonnes in 1956 to almost zero in 1970;[14] that affected the ecosystem not only of the Norwegian Sea but also of the Barents Sea.[19]

الثدييات والطيور

الأنشطة البشرية

Norway, Iceland, and Denmark/Faroe Islands share the territorial waters of the Norwegian Sea, with the largest part belonging to the first. Norway has claimed twelve-mile limit as territorial waters since 2004 and an exclusive economic zone of 200 miles since 1976. Consequently, due to the Norwegian islands of Svalbard and Jan Mayen, the southeast, northeast and northwest edge of the sea fall within Norway. The southwest border is shared between Iceland and Denmark/Faroe Islands.[20]

According to the Føroyingasøga, Norse settlers arrived on the islands around the 8th Century. King Harald Fairhair is credited with being the driving force to colonize these islands as well as others in the Norwegian sea.[21]

The largest damage to the Norwegian Sea was caused by extensive fishing, whaling, and pollution. Other contamination is mostly by oil and toxic substances,[20] but also from the great number of ships sunk during the two world wars.[22] The environmental protection of the Norwegian Sea is mainly regulated by the OSPAR Convention.[20]

صيد الأسماك والحيتان

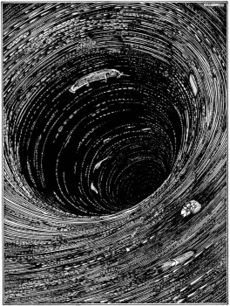

Fishing has been practised near the Lofoten archipelago for hundreds of years. The coastal waters of the remote Lofoten islands are one of the richest fishing areas in Europe, as most of the Atlantic cod swims to the coastal waters of Lofoten in the winter to spawn. So in the 19th century, dried cod was one of Norway's main exports and by far the most important industry in northern Norway. Strong sea currents, maelstroms, and especially frequent storms made fishing a dangerous occupation: several hundred men died on the "Fatal Monday" in March 1821, 300 of them from a single parish, and about a hundred boats with their crews were lost within a short time in April 1875.[23]

Over the last century, the Norwegian Sea has been suffering from overfishing. In 2018, 41% of stocks were excessively harvested.[24] Two out of sixteen of the Total Allowed Catches (TACs) agreed upon by the European Union (EU) and Norway follow scientific advice. Nine of those TACs are at least 25% above scientific advice. While the other five are set above scientific evidence when excluding landing obligation.[25] Under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), the EU committed to phase out overfishing by 2015, 2020 at the absolute latest.[26] As of 2019, the EU was reported to not be on path to achieving that goal.

Whaling was also important for the Norwegian Sea. In the early 1600s, the Englishman Stephen Bennet started hunting walrus at Bear Island. In May 1607 the Muscovy Company, while looking for the Northwest Passage and exploring the sea, discovered the large populations of walrus and whales in the Norwegian Sea and started hunting them in 1610 near Spitsbergen.[27] Later in the 17th century, Dutch ships started hunting bowhead whales near Jan Mayen; the bowhead population between Svalbard and Jan Mayen was then about 25,000 individuals.[28] Britons and Dutch were then joined by Germans, Danes, and Norwegians.[27] Between 1615 and 1820, the waters between Jan Mayen, Svalbard, Bear Island, and Greenland, between the Norwegian, Greenland, and Barents Seas, were the most productive whaling area in the world. However, extensive hunting had wiped out the whales in that region by the early 20th century.[29]

الوحوش والدرادير الضخمة

الاستكشاف

الملاحة

انخفضت الملاحة عبر البحر النرويجي بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية وتكثفت فقط في الستينيات والسبعينيات من القرن الماضي مع توسع الأسطول الشمالي السوڤيتي، والذي انعكس في التدريبات البحرية المشتركة الرئيسية لأساطيل شمال البلطيق السوفيتية في البحر النرويجي. فكان البحر بوابة البحرية السوڤيتية إلى المحيط الأطلسي وبالتالي إلى الولايات المتحدة ، وكان ميناء مورمانسك السوڤيتي الرئيسي يقع مباشرة وراء حدود بحري النرويج وبارنتس.[30] أدت الإجراءات المضادة التي اتخذتها دول الناتو إلى وجود بحري كبير في البحر النرويجي وألعاب القط والفأر المكثفة بين الطائرات والسفن السوڤيتية وحلف شمال الأطلسي، وخصوصاً الغواصات.[31] من مخلفات الحرب الباردة في بحر النرويج، الغواصة النووية السوڤيتية K-278 Komsomolets، التي غرقت في عام 1989 جنوب غرب جزيرة الدب، على الحدود بين بحري النرويج وبارنتس. وقد شكـَّل وجود مواد مشعة على متنها خطراً محتملاً للنباتات والحيوانات.[32]

بحر النرويج هو جزء من الطريق البحري الشمالي للسفن من الموانئ الأوروپية إلى آسيا. مسافة الإبحار من روتردام إلى طوكيو هي 21,100 كم عبر قناة السويس وفقط 14,100 كم عبر بحر النرويج. الجليد البحري مشكلة شائعة في بحار القطب الشمالي ، ولكن لوحظت ظروف خالية من الجليد على طول الطريق الشمالي بأكمله في نهاية أغسطس 2008، ولعل ذلك هو بسبب الاحترار العالمي.[33] تخطط روسيا لتوسيع إنتاجها النفطي البحري في القطب الشمالي، مما سيزيد من حركة الناقلات عبر البحر النرويجي إلى الأسواق في أوروبا وأمريكا؛ ومن المتوقع أن يرتفع عدد شحنات النفط عبر شمال بحر النرويج من 166 شحنة في عام 2002 إلى 615 شحنة في عام 2015.[34]

النفط والغاز

لم تعد أهم منتجات بحر النرويج هي الأسماك ، ولكن النفط وخاصة الغاز الموجود تحت قاع المحيط.[35] بدأت النرويج إنتاج النفط تحت سطح البحر في عام 1993 ، تلاه تطوير حقل هولدرا للغاز في عام 2001.[36] يشكل العمق الكبير والمياه القاسية للبحر النرويجي تحديات فنية كبيرة للحفر البحري.[37] في حين تم إجراء حفر على أعماق تتجاوز 500 متر منذ عام 1995، لم يتم استكشاف سوى عدد قليل من حقول الغاز العميقة تجارياً. أهم مشروع حالي هو أورمن لانگه (عمق 800-1100 متر) ، حيث بدأ إنتاج الغاز في عام 2007. باحتياطيات 4.0×1011 m3 (1.4×1013 cu ft)، فهو حقل غاز رئيسي للنرويج. وهو مربوط بخط أنابيب لانگلد، الذي هو حالياً أطول خط أنابيب في العالم تحت الماء، ومن خلاله يرتبط بالشبكة الرئيسية لخطوط أنابيب الغاز الأوروپية.[38][39] وهناك العديد من حقول الغاز الأخرى قيد التطوير. ففي 2019، يوجد ما يُقدر بنحو 6.5 مليون م³ من النفط الخام في بحر النرويج، مع توقع زيادة إنتاج النفط في المنطقة حتى عام 2025. التحدي الخاص هو حقل كريستين، حيث تصل درجة الحرارة إلى 170 درجة مئوية وضغط الغاز يتجاوز 900 بار (900 ضعف الضغط العادي).[37] وإلى الشمال نجد نورنه و سنوڤيت.

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب Norwegian Sea, الموسوعة السوڤيتية العظمى (بالروسية)

- ^ Norwegian Sea, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- ^ ICES, 2007, p. 1

- ^ Westerly storms warm Norway Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. The Research Council of Norway. Forskningsradet.no (3 September 2012). Retrieved on 2013-03-21.

- ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Terje Thornes and Oddvar Longva The origin of the coastal zone in: Sætre, 2007, pp. 35–43

- ^ أ ب ت Blindheim, 1989, pp. 366–382

- ^ Tyler, 2003, pp. 240–260

- ^ أ ب Aken, 2007, pp. 131–138

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTyler - ^ Skreslet & NATO, 2005, p. 93

- ^ Ronald E. Hester, Roy M. Harrison Biodiversity Under Threat, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2007 ISBN 0-85404-251-2, p. 96

- ^ http://bse.sci-lib.com/article082535.html الموسوعة السوفيتية العظمى

- ^ أ ب Skreslet & NATO, 2005, pp. 103–114

- ^ Andrea Schröder-Ritzrau et al., Distribution, export and alteration of plankton in the Norwegian Sea Fossiliziable. Schaefer, 2001, pp. 81–104

- ^ ICES, 2007, pp. 5–8

- ^ Blindheim, 1989, pp. 382–401

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWefer - ^ Olav Schram Stokke Governing High Seas Fisheries: The Interplay of Global and Regional regime, Oxford University Press, 2001 ISBN 0-19-829949-4, pp. 241–255

- ^ أ ب ت Alf Håkon Noel The Performance of Exclusive Economic Zones – The Case of Norway in: Syma A. Ebbin et al. A Sea Change: The Exclusive Economic Zone and Governance Institutions for Living Marine Resources, Springer, 2005 ISBN 1-4020-3132-7

- ^ "Archaeology of Viking Age Faroe Islands – Projekt Forlǫg" (in التشيكية). 2 June 2016. Retrieved 2020-12-09.

- ^ Tyler, 2003, p. 434

- ^ Tim Denis Smith Scaling Fisheries: The Science of Measuring the Effects of Fishing, 1855–1955, Cambridge University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-521-39032-X, pp. 10–15

- ^ "EU still far from phasing out overfishing by 2020". Oceana Europe (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ "EU-Norway agreement the worst outcome for fish stocks in ten years". Our Fish (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ "Depleted fish stocks can't wait. The EU and Norway need to commit to ending overfishing now ǀ View". euronews (in الإنجليزية). 2019-12-02. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ أ ب Richards, 2006, pp. 589–596

- ^ Richards, 2006, pp. 574–580

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJohnson95 - ^ Joel J. Sokolsky Seapower in the Nuclear Age: The United States Navy and NATO, 1949–80 Taylor & Francis, 1991 ISBN 0-415-00806-9, pp. 83–87

- ^ Olav Riste. NATO's Northern Front Line in 1980s in: Olav Njølstad: The Last Decade of the Cold War: From Conflict Escalation to Conflict Transformation, Routledge, 2004 ISBN 0-7146-8539-9, pp. 360–371

- ^ Hugh D. Livingston: Marine Radioactivity Elsevier, 2004 ISBN 0-08-043714-1, p. 92

- ^ Seidler, Christoph (August 27, 2008). "Northeast – and the Northwest Passage ice-free for the first time at the same time". Der Spiegel. Retrieved July 21, 2011.

- ^ Leichenko, Robin M. & Karen L. O'Brien: Environmental Change and Globalization ISBN 0-19-517732-0, p. 99

- ^ Jerome D. Davis. Changing World of Oil: An Analysis of Corporate Change and Adaptation Ashgate Publishing, 2006 ISBN 0-7546-4178-3, p. 139

- ^ Ann Genova The Politics of the Global Oil Industry, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005 ISBN 0-275-98400-1, pp. 202–209

- ^ أ ب Geo ExPro November 2004. Kristin – A Tough Lady Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- ^ Country Analysis Briefs: Norway, Energy Information Administration

- ^ Moskwa, Wojciech (September 13, 2007). "Norway's Ormen Lange gas starts flowing to Britain". Reuters. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

المراجع

- van Aken, Hendrik Mattheus (2007). The Oceanic Thermohaline Circulation: An Introduction. Springer. ISBN 0-387-36637-7.

- Blindheim, Johan (1989). "Ecological Features of the Norwegian Sea". In Louis René Rey; et al. (eds.). Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the Comité arctique international, 13–15 May 1985. Brill Publishers. pp. 366–401. ISBN 90-04-08281-6.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (2007). The Barents Sea and the Norwegian Sea (PDF). ICES Advice 2007. Vol. 3.

- Johnson, Arne Odd (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 0-905838-23-8.

- Klinowska, Margaret, ed. (1991). Dolphins, Porpoises and Whales of the World: The IUCN Red Data Book. ISBN 2-88032-936-1.

- Mills, Eric L. (2001). Helen M. Rozwadowski & David K. van Keuren (ed.). The Machine in Neptune's Garden: Historical Perspectives on Technology and the Marine Environment. Science History Publications/USA. ISBN 0-88135-372-8.

- Richards, John F. (2006). The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24678-0.

- Sætre, Roald, ed. (2007). The Norwegian Coastal Current – Oceanography and Climate. Trondheim: Tapir Academic Press. ISBN 978-82-519-2184-8.

- Schaefer, Priska (2001). The Northern North Atlantic: A Changing Environment. Springer. ISBN 3-540-67231-1.

- Skreslet, Stig; North Atlantic Treaty Organization (2005). Jan Mayen Iceland in Scientific Focus. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-2956-X.

- Tyler, Paul A. (2003). Ecosystems of the Deep Oceans: Ecosystems of the World. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-82619-X.

وصلات خارجية

Media related to Norwegian Sea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Norwegian Sea at Wikimedia Commons

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 التشيكية-language sources (cs)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing نرويجية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- بحر النرويج

- بحار هامشية في المحيط الأطلسي

- بحار هامشية في المحيط المتجمد الشمالي

- بحار النرويج