الثالوث

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الروحانية |

|---|

| المؤثرات |

| أبحاث |

في المسيحية، الثالوث الأقدس هو عقيدة مسيحية تقول ان الله هو إله واحد متواجد، في نفس الوقت والى الأبد، في ثلاثة اقانيم: الآب (المصدر، صاحب العظمى الابدية) والابن (الكلمة الازلية، متجسد بيسوع الناصري) والروح القدس (البارقيلط أو روح الله الذي يثبت المؤمنين).

منذ القرن الرابع، في الكنيستين المسيحيتين الشرقية والغربية، هذه العقيدة تنص على ان الله واحد في ثلاثة اقانيم .

As the Fourth Lateran Council declared, it is the Father who begets, the Son who is begotten, and the Holy Spirit who proceeds.[1][2][3] In this context, one essence/nature defines what God is, while the three persons define who God is.[4][5] This expresses at once their distinction and their indissoluble unity. Thus, the entire process of creation and grace is viewed as a single shared action of the three divine persons, in which each person manifests the attributes unique to them in the Trinity, thereby proving that everything comes "from the Father", "through the Son", and "in the Holy Spirit".[6]

This doctrine is called Trinitarianism, and its adherents are called Trinitarians, while its opponents are called antitrinitarians or nontrinitarians and are considered non-Christian by most mainline groups. Nontrinitarian positions include Unitarianism, binitarianism and modalism. The theological study of the Trinity is called "triadology" or "Trinitarian theology".[7][8]

While the developed doctrine of the Trinity is not explicit in the books that constitute the New Testament, the New Testament possesses a triadic understanding of God[9] and contains a number of Trinitarian formulas.[10][11] The doctrine of the Trinity was first formulated among the early Christians (mid-2nd century and later) and fathers of the Church as they attempted to understand the relationship between Jesus and God in their scriptural documents and prior traditions.[12]

العهد القديم

The Old Testament has been interpreted as referring to the Trinity in many places. For example, in the Genesis creation narrative, specifically the first-person plural pronouns in Genesis 1:26–27 and Genesis 3:22 ('Let us make man in our image [...] the man is become as one of us').

"Then God said, 'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over the livestock and over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.' [...] "Then the LORD God said, 'Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil [...]"

— Genesis 1:26, 3:22 ESV

A traditional Christian interpretation of these pronouns is that they refer to a plurality of persons within the Godhead. Biblical commentator Victor P. Hamilton outlines several interpretations, including the most widely held among Biblical scholars, which is that the pronouns do not refer to other persons within the Godhead but to the 'heavenly court' of Isaiah 6. Theologians Meredith Kline[13] and Gerhard von Rad argue for this view; as von Rad says, 'The extraordinary plural ("Let us") is to prevent one from referring God's image too directly to God the Lord. God includes himself among the heavenly beings of his court and thereby conceals himself in this majority.'[14] Hamilton notes that this interpretation assumes that Genesis 1 is at variance with Isaiah 40:13–14, Who has measured the Spirit of the Lord, or what man shows him his counsel? Whom did he consult, and who made him understand? Who taught him the path of justice, and taught him knowledge, and showed him the way of understanding? That is, if the plural pronouns of Genesis 1 teach that God consults and creates with a 'heavenly court', then it contradicts the statement in Isaiah that God seeks the counsel of nobody. According to Hamilton, the best interpretation 'approaches the Trinitarian understanding but employs less direct terminology'.[15] Following D. J. A. Clines, he states that the plural reveals a 'duality within the Godhead' that recalls the 'Spirit of God' mentioned in verse 2, And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters. Hamilton also says that it is unreasonable to assume that the author of Genesis was too theologically primitive to deal with such a concept as 'plurality within unity';[15] Hamilton thus argues for a framework of progressive revelation, in which the doctrine of the Trinity is revealed at first obscurely then plainly in the New Testament.

Another of these places is the prophecy about the Messiah in Isaiah 9. The Messiah is called "Wonderful, Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace". Some Christians see this verse as meaning the Messiah will represent the Trinity on earth. This is because Counselor is a title for the Holy Spirit (John 14:26), the Trinity is God, Father is a title for God the Father, and Prince of Peace is a title for Jesus. This verse is also used to support the Deity of Christ.[16]

Another verse used to support the Deity of Christ is[17]

I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a son of man, and he came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before him. And to him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him; his dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and his kingdom one that shall not be destroyed.

— Daniel 7:13–14 ESV

This is because both the Ancient of Days (God the Father) and the Son of Man (Jesus, Matt 16:13) have an everlasting dominion, which is ascribed to God in Psalm 145:13.[18]

People also see the Trinity when the Old Testament refers to God's word (Psalm 33:6), His Spirit (Isaiah 61:1), and Wisdom (Proverbs 9:1), as well as narratives such as the appearance of the three men to Abraham.[19] However, it is generally agreed among Trinitarian Christian scholars that it would go beyond the intention and spirit of the Old Testament to correlate these notions directly with later Trinitarian doctrine.[20]

Some Church Fathers believed that a knowledge of the mystery was granted to the prophets and saints of the Old Testament and that they identified the divine messenger of Genesis 16:7, Genesis 21:17, Genesis 31:11, Exodus 3:2, and Wisdom of the sapiential books with the Son, and "the spirit of the Lord" with the Holy Spirit.[20]

Other Church Fathers, such as Gregory Nazianzen, argued in his Orations that the revelation was gradual, claiming that the Father was proclaimed in the Old Testament openly, but the Son only obscurely, because "it was not safe, when the Godhead of the Father was not yet acknowledged, plainly to proclaim the Son".[21]

Genesis 18–19 has been interpreted by Christians as a Trinitarian text. The narrative has the Lord appearing to Abraham, who was visited by three men.[22] In Genesis 19, "the two angels" visited Lot at Sodom.[23] The interplay between Abraham on the one hand and the Lord/three men/the two angels on the other was an intriguing text for those who believed in a single God in three persons. Justin Martyr and John Calvin similarly interpreted it as such that Abraham was visited by God, who was accompanied by two angels.[24] Justin supposed that the God who visited Abraham was distinguishable from the God who remains in the heavens but was nevertheless identified as the (monotheistic) God. Justin interpreted the God who visited Abraham as Jesus, the second person of the Trinity.[25]

Augustine, in contrast, held that the three visitors to Abraham were the three persons of the Trinity.[24] He saw no indication that the visitors were unequal, as would be the case in Justin's reading. Then, in Genesis 19, two of the visitors were addressed by Lot in the singular: "Lot said to them, 'Not so, my lord'" (Gen. 19:18).[24] Augustine saw that Lot could address them as one because they had a single substance despite the plurality of persons.[أ]

Christians interpret the theophanies, or appearances of the Angel of the Lord, as revelations of a person distinct from God, who is nonetheless called God. This interpretation is found in Christianity as early as Justin Martyr and Melito of Sardis and reflects ideas that were already present in Philo.[26] The Old Testament theophanies were thus seen as Christophanies, each a "preincarnate appearance of the Messiah".[27]

John William Colenso argued that the non-canonical Book of Enoch implies a Trinitarian-esque view of God, seeing the "Lord of the spirits", the "Elected one" and the "Divine power" each partaking of the name of God.[28]

العهد الجديد

Jesus in the New Testament

In the Pauline epistles, the public, collective devotional patterns towards Jesus in the early Christian community are reflective of Paul's perspective on the divine status of Jesus in what scholars have termed a "binitarian" pattern or shape of devotional practice (worship) in the New Testament, in which "God" and Jesus are thematized and invoked.[29] Jesus receives prayer (1 Corinthians 1:2; 2 Corinthians 12:8–9), the presence of Jesus is confessionally invoked by believers (1 Corinthians 16:22; Romans 10:9–13; Philippians 2:10–11), people are baptized in Jesus' name (1 Corinthians 6:11; Romans 6:3), Jesus is the reference in Christian fellowship for a religious ritual meal (the Lord's Supper; 1 Corinthians 11:17–34).[30] Jesus is described as "existing in the very form of God" (Philippians 2:6), and having the "fullness of the Deity [living] in bodily form" (Colossians 2:9). Jesus is also in some verses directly called God (Romans 9:5,[31] Titus 2:13, 2 Peter 1:1).

آيات إنجيلية تؤيد عقيدة الثالوث الأقدس

- متى 28:19 : فاذهبوا و تلمذوا جميع الامم و عمدوهم باسم الاب و الابن و الروح القدس

- يوحنا 1:1 : " فِي الْبَدْءِ كَانَ الْكَلِمَةُ، وَالْكَلِمَةُ كَانَ عِنْدَ اللهِ. وَكَانَ الْكَلِمَةُ هُوَ اللهُ . " مع يوحنا 1:14 : "وَالْكَلِمَةُ صَارَ بَشَراً، وَخَيَّمَ بَيْنَنَا، وَنَحْنُ رَأَيْنَا مَجْدَهُ، مَجْدَ ابْنٍ وَحِيدٍ عِنْدَ الآبِ، وَهُوَ مُمْتَلِىءٌ بِالنِّعْمَةِ وَالْحَقِّ. " و يوحنا 1:18 "مَا مِنْ أَحَدٍ رَأَى اللهَ قَطُّ. وَلَكِنَّ الابْنَ الْوَحِيدَ، الَّذِي فِي حِضْنِ الآبِ، هُوَ الَّذِي كَشَفَ عَنْهُ. "

- يوحنا 8:58 : " أَجَابَهُمْ: الْحَقَّ الْحَقَّ أَقُولُ لَكُمْ: إِنَّنِي كَائِنٌ مِنْ قَبْلِ أَنْ يَكُونَ إِبْرَاهِيمُ». "

Nontrinitarian Christian beliefs

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to Christian belief systems that reject the doctrine of the Trinity as found in the Nicene Creed as not having a scriptural origin. Nontrinitarian views differ widely on the nature of God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit.

Various nontrinitarian views, such as Adoptionism and Arianism existed prior to the formal definition of the Trinity doctrine in AD 325, 360, and 431, at the Councils of Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus, respectively.[32] Adoptionists believed that Jesus Christ only became divine at his baptism, ressurection or ascension.[33] Adherents of Arianism postulated that only God is independent of his existence. Since the Son is dependent, he should, therefore, be called a creature.[34]

Other Abrahamic religions' views

Judaism

Judaism maintains a tradition of monotheism that excludes the possibility of a Trinity.[35] In Judaism, God is understood to be the absolute one, indivisible, and incomparable being, which is the ultimate cause of all existence.

Some Kabbalist writings have a Trinitarian-esque view of God, speaking of "stages of God's being, aspects of the divine personality", with God being "three hidden lights, which constitute one essence and one root". Some Jewish philosophers additionally saw God as a "thinker, thinking and thought", taking from Augustinian analogies.[36] The Zohar additionally says that "God is they, and they are it".

Philo of Alexandria recognized a threefold character of God but had many differences from the Christian view of the Trinity.[37]

Islam

Islam considers Jesus to be a prophet, but not divine,[35] and God to be absolutely indivisible (a concept known as tawhid).[38] Several verses of the Quran state that the doctrine of the Trinity is blasphemous.

Indeed, disbelievers have said, "Truly, Allah is Messiah, son of Mary." But Messiah said, "Children of Israel! Worship Allah, my lord and your lord." Indeed, whoever associates partners with Allah, surely Allah has forbidden them from Heaven, and fire is their resort. And there are no helpers for the wrongdoers. Indeed, disbelievers have said, "Truly, Allah is a third of three." Yet, there is no god except One God, and if they do not desist from what they say, a grievous punishment befalls the disbelievers. Will they not turn to Allah and ask His forgiveness? For Allah is most forgiving and merciful. Is not Messiah, son of Mary, only a messenger? Indeed, messengers had passed away prior to him. And his mother was an upright woman. They both ate food. Observe how we explain the signs for them, then observe how they turn away (from truth)!

— Quran 5:72–75[39]

Interpretation of these verses by modern scholars has been varied. Verse 5:73 has been interpreted as a potential criticism of Syriac literature that references Jesus as "the third of three" and thus an attack on the view that Christ was divine.[40] Another interpretation is that this passage should be studied from a rhetorical perspective; so as not to be an error, but an intentional misrepresentation of the doctrine of the Trinity in order to demonstrate its absurdity from an Islamic perspective.[41] David Thomas states that verse 5:116 need not be seen as describing actually professed beliefs, but rather, giving examples of shirk (claiming divinity for beings other than God) and a "warning against excessive devotion to Jesus and extravagant veneration of Mary, a reminder linked to the central theme of the Qur'an that there is only one God and He alone is to be worshipped".[38] When read in this light, it can be understood as an admonition, "Against the divinization of Jesus that is given elsewhere in the Qur'an and a warning against the virtual divinization of Mary in the declaration of the fifth-century church councils that she is 'God-bearer'." Similarly, Gabriel Reynolds, Sidney Griffith, and Mun'im Sirry argue that this Quranic verse is to be understood as an intentional caricature and rhetorical statement to warn of the dangers of deifying Jesus or Mary.[42][43]

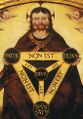

Artistic depictions

The Trinity is most commonly seen in Christian art with the Spirit represented by a dove, as specified in the Gospel accounts of the Baptism of Christ; he is nearly always shown with wings outspread. However, depictions using three human figures appear occasionally in most periods of art.[44]

The Father and the Son are usually differentiated by age and later by dress, but this too is not always the case. The usual depiction of the Father as an older man with a white beard may derive from the biblical Ancient of Days, which is often cited in defense of this sometimes controversial representation. However, in Eastern Orthodoxy, the Ancient of Days is usually understood to be God the Son, not God the Father (see below)—early Byzantine images show Christ as the Ancient of Days,[45] but this iconography became rare. When the Father is depicted in art, he is sometimes shown with a halo shaped like an equilateral triangle instead of a circle. The Son is often shown at the Father's right hand (Acts 7:56). He may be represented by a symbol—typically the Lamb (agnus dei) or a cross—or on a crucifix, so that the Father is the only human figure shown at full size. In early medieval art, the Father may be represented by a hand appearing from a cloud in a blessing gesture, for example, in scenes of the Baptism of Christ. Later, in the West, the Throne of Mercy (or "Throne of Grace") became a common depiction. In this style, the Father (sometimes seated on a throne) is shown supporting either a crucifix[46] or, later, a slumped crucified Son, similar to the Pietà (this type is distinguished in German as the Not Gottes)[47] in his outstretched arms, while the Dove hovers above or in between them. This subject continued to be popular until at least the 18th century.

By the end of the 15th century, larger representations, other than the Throne of Mercy, became effectively standardized, showing an older figure in plain robes for the Father, Christ with his torso partly bare to display the wounds of his Passion, and the dove above or around them. In earlier representations, both Father, especially, and Son often wear elaborate robes and crowns. Sometimes the Father alone wears a crown or even a papal tiara.

In the later part of the Christian Era, in Renaissance European iconography, the Eye of Providence began to be used as an explicit image of the Christian Trinity and associated with the concept of Divine Providence. Seventeenth-century depictions of the Eye of Providence sometimes show it surrounded by clouds or sunbursts.[48]

Image gallery

Depiction of Trinity from Saint Denis Basilica in Paris (12th century)

The Holy Trinity in an angelic glory over a landscape, by Lucas Cranach the Elder (d. 1553)

God the Father (top), and the Holy Spirit (represented by a dove) depicted above Jesus Painting by Francesco Albani (d. 1660)

God the Father (top), the Holy Spirit (a dove), and the child Jesus, painting by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (d. 1682)

Pope Clement I prays to the Trinity, in a typical post-Renaissance depiction by Gianbattista Tiepolo (d. 1770)

Atypical depiction of the Trinity where the Son is identified by a lamb, the Father an Eye of Providence, and the Spirit a dove

13th-century depiction of the Trinity from a Roman de la Rose manuscript

Representation of the Trinity in the form of the mercy seat (epitaph from 1549)

The Trinity by Russian icon painter Andrei Rublev, early 15th century: this portrayal of the three angels who visited Abraham at the Oak of Mamre (Genesis 18:1–8)

Renaissance painting by Jerónimo Cosida depicting Jesus as a triple deity Inner text: The Father is God; the Son is God; the Holy Spirit is God

An anonymous 18th century Catholic painting from the Peruvian Cuzco School. This work depicts the Holy Triune God; one in essence, with three persons; holding the theological diagram of the Shield of the Trinity.

In architecture

Many Christian churches have three doors symbolizing the Trinity. Other architectural features, such as windows or steps, are also grouped into three for this reason.[50] This practice originated in spolia churches that were built from, and on top of, the remains of ancient pre-Christian holy structures.[51]

Examples are the three royal doors inside Eastern churches and the trio of doors in the façade of many cathedrals. A triangular floor plan can also symbolize the Trinity, as in Heiligen-Geist-Kapelle in Austria.[52]

In literature

The Trinity has traditionally been a subject matter of strictly theological works focused on proving the doctrine of the Trinity and defending it against its critics. In recent years, however, the Trinity has made an entrance into the world of (Christian) literature through books such as The Shack.

See also

- Ahuric triad

- Ayyavazhi Trinity

- Formal distinction

- Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)

- Saint Patrick

- Social trinitarianism

- Three Pure Ones

- Trikaya, the three Buddha bodies

- Trimurti, Hinduism

- Tridevi, Hinduism

- Trinitarian Order

- Trinitarian universalism

- Trinity Sunday, a day to celebrate the doctrine

- Triple deity, an associated term in comparative religion

- Triquetra, a symbol sometimes used to represent the Trinity

- Tritheism

References

Notes

- ^ Augustine had poor knowledge of the Greek language, and no knowledge of Hebrew. So he trusted the Septuagint, which differentiates between κύριοι ('lords', vocative plural) and κύριε ('lord', vocative singular), even if the Hebrew verbal form, נא-אדני (na-adoni), is exactly the same in both cases.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Augustine1" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Augustine2" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "Arius" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

<ref> ذو الاسم "1john5" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.Citations

- ^ Fourth Lateran Council (1215) List of Constitutions: 2. On the error of abbot Joachim. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit | EWTN". EWTN Global Catholic Television Network. Archived from the original on 3 September 2004. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Fathers, Council (11 November 1215). Fourth Lateran Council: 1215 Council Fathers. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ "Frank Sheed, Theology and Sanity". Ignatiusinsight.com. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Sheed, Frank J. (11 January 1978). Theology & Sanity. Bloomsbury Publishing (published 1978). ISBN 978-0-8264-3882-9. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

Nature answers the question what we are; person answers the question who we are. [...] Nature is the source of our operations, person does them.

- ^ Blanch, Jorge (2024-11-24). "The Trinity: Historical Development and Debates". The Mythic Cross. Archived from the original on 1 December 2024. Retrieved 2024-11-24.

- ^ Januariy, Archimandrite (2003), Stewart, Melville Y., ed., The Elements of Triadology in the New Testament, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 99–106, doi:, ISBN 978-94-017-0393-2, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-017-0393-2_10, retrieved on 2025-03-07

- ^ Westhuizen, Henco van der (2022-12-15). Reader in Trinitarian Theology. UJ Press. ISBN 978-1-77641-949-4.

- ^ Hurtado 2010, pp. 99–110.

- ^ Januariy 2013, p. 99.

- ^ Archimandrite Janurariy (Ivliev) (9 March 2013) [2003]. "The Elements of Triadology in the New Testament". In Stewart, Melville Y. (ed.). The Trinity: East/West Dialogue. Volume 24 of Studies in Philosophy and Religion. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media (published 2013). p. 100. ISBN 9789401703932. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

Trinitarian formulas are found in New Testament books such as 1 Peter 1:2; and 2 Cor 13:13. But the formula used by John the mystery-seer is unique. Perhaps it shows John's original adaptation of Paul's dual formula.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, pp. 644–648.

- ^ Kline, Meredith G. (2016). Genesis: A New Commentary. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers Marketing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-61970-852-5.

- ^ von Rad, Gerhard (1961). Genesis. Translated by Marks, John H. Chatham, Kent: W. L. Jenkins. p. 57.

- ^ أ ب Hamilton, Victor P. (1990). The Book of Genesis: chapters 1–17. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-8028-2521-6.

- ^ "For to Us a Child Is Born: The Meaning of Isaiah 9:6". Zondervan Academic. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "Doctrine of the Last Things (Part 1): The Second Coming of Christ". Reasonable Faith. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: Psalm 145:13 – New International Version". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2022.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 1652.

- ^ أ ب Joyce 1912.

- ^ Gregory Nazianzen, Orations, 31.26

- ^ Genesis 18:1–2

- ^ Genesis 19

- ^ أ ب ت Watson, Francis. Abraham's Visitors: Prolegomena to a Christian Theological Exegesis of Genesis 18–19 Archived 2 ديسمبر 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Church Fathers: Dialogue with Trypho, Chapters 55-68 (Justin Martyr)". New Advent. Retrieved 2025-03-07.

- ^ Hurtado 2005, pp. 573–578.

- ^ "Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology: Angel of the Lord". Studylight.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Colenso, John William (2022). The Pentateuch and Book of Joshua: Critically examined. Part 3. Part 4 (2 ed.). Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-375-00420-0.

- ^ Hurtado 2010, pp. [1].

- ^ Hurtado 2005, pp. 134–152.

- ^ "Is Jesus God? (Romans 9:5)". billmounce.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ von Harnack, Adolf (1 March 1894). "History of Dogma". Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2007.

[In the 2nd century,] Jesus was either regarded as the man whom God hath chosen, in whom the Deity or the Spirit of God dwelt, and who, after being tested, was adopted by God and invested with dominion, (Adoptionist Christology); or Jesus was regarded as a heavenly spiritual being (the highest after God) who took flesh, and again returned to heaven after the completion of his work on earth (pneumatic Christology)

- ^ Coonrad, Sharon Watters (1999). Adoptionism: The History of a Doctrine (in الإنجليزية). University of Iowa.

- ^ Gregg, Robert C. (2006-10-19). Arianism: Historical and Theological Reassessments: Papers from The Ninth International Conference on Patristic Studies (in الإنجليزية). Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59752-961-7.

- ^ أ ب Glassé & Smith 2003, pp. 239–241.

- ^ "Trinity > Judaic and Islamic Objections (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ The Jewish Quarterly Review. Macmillan. 1895.

- ^ أ ب Thomas 2006, "Trinity".

- ^ "Quran 5:72–75". The Noble Qur'an. Archived from the original on 10 June 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Griffith 2012, note 7.

- ^ Zebiri 2006, p. 274.

- ^ Sirry 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Neuwirth & Sells 2016, pp. 300–304.

- ^ Schiller 1971, figs 1; 5–16.

- ^ Cartlidge & Elliott 2001, p. 240.

- ^ Schiller 1971, pp. 122–124 and figs 409–414.

- ^ Schiller 1971, pp. 219–224 and figs 768–804.

- ^ Potts 1982, pp. 68–78.

- ^ "The Front Entrance". The Cathedral of Saint John the Evangelist. Cleveland, Ohio. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

A central doctrine of the Catholic Faith is symbolized in the three arches of the entrance the Three Persons of the Blessed Trinity. The center door symbolizes the Father, the north door the Son, and the south door the Holy Spirit.

- ^ Kennedy, Katherine (1919). Christian Symbols: Some Notes on Their Origin and Meaning. A. R. Mowbray. p. 12.

- ^ Hansen, Maria Fabricius (2015). The Spolia Churches of Rome: Recycling Antiquity in the Middle Ages. p. 59.

- ^ "Sanierung Heiligen-Geist-Kapelle, Bruck an der Mur" (in الألمانية). Bruck an der Mur. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "oxforddictionaries.com" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "def-lateran1" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "against-praxeas1" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "ignatius" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "first-apology" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "theophilus2" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "tertullian" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "BEoWR" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "patristics" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "patristics1" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "patristics2" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "patristics3" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "patristics4" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "patristics5" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "athanasian-creed" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "hilary-john" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "despiritu" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "athanasius3" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "basil" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "bbc-john" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

<ref> ذو الاسم "de-trinitate1" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.Sources

- Allison, Dale C. Jr (2016). "Acts 9: 1–9, 22: 6–11, 26: 12–18: Paul and Ezekiel". Journal of Biblical Literature. 135 (4): 807–826. doi:10.15699/jbl.1354.2016.3138.

- Aquinas, Thomas (1975). Summa Contra Gentiles: Book 4: Salvation Chapter 4. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0-268-07482-1.

- Arendzen, John Peter (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Augustine of Hippo (2002). Augustine: On the Trinity Books 8–15. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79665-1.

- Barnard, L. W. (1970). "The Antecedents of Arius". Vigiliae Christianae. 24 (3): 172–188. doi:10.2307/1583070. ISSN 0042-6032. JSTOR 1583070.

- Barth, Karl (1975). The Doctrine of the Word of God: (prolegomena to Church Dogmatics, Being Volume I, 1). T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-09013-3.

- Basil of Caesarea (1980). On the Holy Spirit. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-913836-74-3.

- Bauckham, Richard (2017). "Is "High Human Christology" Sufficient? A Critical Response to J. R. Daniel Kirk's A Man Attested by God". Bulletin for Biblical Research. Penn State University Press. 27 (4): 503–525. doi:10.5325/bullbiblrese.27.4.0503. JSTOR 10.5325/bullbiblrese.27.4.0503. S2CID 246577988.

- Brown, Raymond Edward (1970). The Gospel According to John. Vol. 2: XIII to XXI. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-03761-7.

- Carson, Donald Arthur (2000). The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God. Inter-Varsity. ISBN 978-0-85111-975-5.

- Cartlidge, David R.; Elliott, James Keith (2001). Art and the Christian Apocrypha. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23392-7.

- Chadwick, Henry (1993). The Penguin History of the Church: The Early Church. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-023199-1.

- Chapman, Henry Palmer (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Clarke, William Newton (1900). An Outline of Christian Theology (8th ed.). New York: Scribner.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). "Trinity, doctrine of the". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Daley, Brian E. (2009). "The Persons in God and the Person of Christ in Patristic Theology: An Argument for Parallel Development". God in Early Christian Thought. Leiden & Boston: Brill. pp. 323–350. ISBN 978-9004174122.

- De Smet, Richard (2010). Ivo Coelho (ed.). Brahman and Person: Essays. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120834590.

- Dimech, Pauline (2019). "9. Von Balthasars Theoaesthetics Applied to Religious Education". In Michael T. Buchanan; Adrian-Mario Gellel (eds.). Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools. Volume II: Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World. Springer. p. 103. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6127-2. ISBN 978-9811361272.

- Dupuis, Jacques; Neuner, Josef (2001). The Christian Faith in the Doctrinal Documents of the Catholic Church (7th ed.). Alba House. ISBN 978-0-8189-0893-4.

- Fee, Gordon (2002). "Paul and the Trinity: The experience of Christ and the Spirit for Paul's Understanding of God". In Davis, Stephen (ed.). The Trinity: An Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Trinity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924612-0.

- Ferguson, Everett (2009). Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2748-7.

- Glassé, Cyril; Smith, Huston (2003). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0190-6.

- Goodman, Roberta Louis; Blumberg, Sherry H. (2002). Teaching about God and Spirituality: A Resource for Jewish Settings. Behrman House. ISBN 978-0-86705-053-0.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (2012). The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3402-0.

- Grudem, Wayne (1994). Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. ISBN 978-0-310-28670-7.

- Harvey, Susan Ashbrook; Hunter, David G. (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927156-6.

- Hays, Richard B. (2014). Reading Backwards: Figural Christology and the Fourfold Gospel Witness. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-4813-0232-6.

- Hoskyns, Sir Edwyn Clement (1967). F. N. Davey (ed.). The Fourth Gospel (2nd ed.). London: Faber & Faber.

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (2012). "On Athanasius". The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. Archived from the original on 27 September 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- Hurtado, Larry (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3167-5.

- Hurtado, Larry (2010). God in New Testament Theology. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-1954-7.

- Hurtado, Larry (2018). "Observations on the "Monotheism" Affirmed in the New Testament". In Beeley, Christopher; Weedman, Mark (eds.). The Bible and Early Trinitarian Theology. Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-2995-9.

- Januariy, Archimandrite (2013). "The Elements of Triadology in the New Testament". In Stewart, M. (ed.). The Trinity: East/West Dialogue. Springer. ISBN 978-9401703932.

- Joyce, George Hayward (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Kitamori, Kazoh (2005). Theology of the Pain of God. Translated by Graham Harrison from the Japanese Kami no itami no shingaku, revised edition 1958, first edition 1946. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-59752-256-4.

- Kupp, David D. (1996). Matthew's Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God's People in the First Gospel. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57007-7.

- Litwa, M. David (2019). How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-24948-4.

- Magliola, Robert (2001). "Two Models of Trinity: French Post-structuralist versus the Historical-critical argued in the Form of a Dialogue". In Oliva Blanchette; Tomonobu Imamichi; George F. McLean (eds.). Philosophical Challenges and Opportunities of Globalization. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: CRVP: Catholic U. of America. ISBN 978-1-56518-129-8.

- Magliola, Robert (2014). Facing Up to Real Doctrinal Difference: How Some Thought-Motifs from Derrida Can Nourish The Catholic-Buddhist Encounter. Angelico Press. ISBN 978-1-62138-079-5.

- Meens, Rob (2016). Religious Franks: Religion and Power in the Frankish Kingdoms: Studies in Honour of Mayke de Jong. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9763-8.

- Metzger, B. M.; Ehrman, B. D. (1968). The Text of New Testament (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-5885009010.

- Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael David (1993). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974391-9.

- Milburn, Robert (1991). Early Christian Art and Architecture. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07412-2.

- Mobley, Joshua (2021). A Brief Systematic Theology of the Symbol. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-70252-4.

- Mulhern, Philip (1967). "Trinity, Holy, Devotion To". In Bernard L. Marthaler (ed.). New Catholic Encyclopedia. McGraw Hill. OCLC 588876554.

- Neuwirth, Angelika; Sells, Michael A. (2016). Qur'ānic Studies Today. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-29566-2.

- Olson, Roger (1999). The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition & Reform. InterVarsity Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8308-1505-0.

sabellian heresy council constantinople.

- Pegis, Anton (1997). Basic writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Hackett Pub. ISBN 978-0-87220-380-8.

- Polkinghorne, John (September 2008). "Book Review: The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief". Theology. 111 (863): 395–396. doi:10.1177/0040571x0811100523. ISSN 0040-571X. S2CID 170563171.

- Pool, Jeff B. (2011) [2009]. God's Wounds. Evil and Divine Suffering. Vol. 2. Havertown, Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-0-227-17360-2.

- Potts, Albert M. (1982). The World's Eye. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 68–78. ISBN 978-0-8131-3130-6.

- Ramelli, Ilaria (2011a). "Origen's anti-subordinationism and its heritage in the Nicene and Cappadocian line". Vigiliae Christianae. 65 (1): 21–49. doi:10.1163/157007210X508103.

- Ramelli, Ilaria (2012). "Origen, Greek Philosophy, and the Birth of the Trinitarian Meaning of Hypostasis". The Harvard Theological Review. 105 (3): 302–350. doi:10.1017/S0017816012000120. JSTOR 23327679. S2CID 170203381.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2014). "On the Presentation of Christianity in the Qurʾān and the Many Aspects of Qur'anic Rhetoric". Al-Bayān – Journal of Qurʾān and Ḥadīth Studies. 12 (1): 42–54. doi:10.1163/22321969-12340003. ISSN 2232-1950.

- Sauvage, George (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Schiller, Gertrud (1971). Iconography of Christian Art. Vol. 1: Christ's Incarnation. Childhood. Baptism. Temptation. Transfiguration. Works and miracles. Lund Humphries. ISBN 978-0-85331-270-3.

- Sim, David C.; Repschinski, Boris (2008). Matthew and his Christian Contemporaries. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-46231-2.

- Simonetti, Manlio; Oden, Thomas C. (2002). Matthew 14–28. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1469-5.

- Sirry, Mun'im (2014). Scriptural Polemics: The Qur'an and Other Religions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-935937-0.

- Thomas, David (2006). "Trinity". Encyclopedia of the Qur'an. Vol. V.

- von Balthasar, Hans (1992). Theo-drama: Theological Dramatic Theory. Vol. 3: Dramatis Personae: Persons in Christ. Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-2281-0.

- von Balthasar, Hans Urs (2000) [1990]. "Preface to the Second Edition". Mysterium Paschale. The Mystery of Easter. Translated with an Introduction by Aidan Nichols, O.P. (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-1-68149-348-0.

- Vondey, Wolfgang (2012). Pentecostalism: A Guide for the Perplexed. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-62731-5.

- Warfield, Benjamin B. (1915). "§ 20 Trinity: The Question of Subordination". In James Orr (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia. Vol. 5. Howard-Severance Company.

- Williams, Rowan (2001). Arius: Heresy and Tradition (2nd ed.). SPCK. ISBN 978-0-334-02850-5.

- Yewangoe, Andreas (1987). Theologia Crucis in Asia: Asian Christian Views on Suffering in the Face of Overwhelming Poverty and Multifaceted Religiosity in Asia. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9062036103.

- Zebiri, Kate (2006). "Argumentation". In Rippin, Andrew (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the Qur'an. Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-7844-0.

Further reading

- Alfeyev, Hilarion (2013). "The Trinitarian Teaching of Saint Gregory Nazianzen". In Stewart, M. (ed.). The Trinity: East/West Dialogue. Springer. ISBN 978-9401703932.

- Bates, Matthew W. (2015). The Birth of the Trinity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-104587-5.

- Bellarmine, Robert (1902). . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- Beeley, Christopher; Weedman, Mark, eds. (2018). The Bible and Early Trinitarian Theology. Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-2996-6.

- Emery, Gilles; Levering, Matthew, eds. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of the Trinity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955781-3.

- Grillmeier, Aloys (1975) [1965]. Christ in Christian Tradition: From the Apostolic Age to Chalcedon (451). Vol. 1 (2nd revised ed.). Atlanta: John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22301-4.

- Fiddes, Paul, Participating in God: a pastoral doctrine of the Trinity (London: Darton, Longman, & Todd, 2000).

- Johnson, Thomas K., "What Difference Does the Trinity Make?" (Bonn: Culture and Science Publ., 2009).

- Hillar, Marian, From Logos to Trinity. The Evolution of Religious Beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian. (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- Holmes, Stephen R. (2012). The Quest for the Trinity: The Doctrine of God in Scripture, History and Modernity. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-3986-5.

- La Due, William J., The Trinity guide to the Trinity (Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 978-1563383953).

- Morrison, M. (2013). Trinitarian Conversations: Interviews With Ten Theologians. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Letham, Robert (2004). The Holy Trinity: In Scripture, History, Theology, and Worship. P & R. ISBN 978-0-87552-000-1.

- O'Collins, Gerald (1999). The Tripersonal God: Understanding and Interpreting the Trinity. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3887-6.

- Olson, Roger E.; Hall, Christopher A. (2002). The Trinity. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4827-7.

- Phan, Peter C., ed. (2011). The Cambridge Companion to the Trinity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87739-8.

- Ramelli, Ilaria (2011). "Gregory of Nyssa's Trinitarian Theology in Illud: Tunc et ipse filius. His Polemic against Arian Subordinationism and the ἀποκατάστασις". Gregory of Nyssa: The Minor Treatises on Trinitarian Theology and Apollinarism. Leiden-Boston: Brill. pp. 445–478. ISBN 978-9004194144.

- So, Damon W. K., Jesus' Revelation of His Father: A Narrative-Conceptual Study of the Trinity with Special Reference to Karl Barth. Archived 14 أكتوبر 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2006). ISBN 184227323X.

- Spirago, Francis (1904). . Anecdotes and Examples Illustrating The Catholic Catechism. Translated by James Baxter. Benzinger Brothers.

- Reeves, Michael (2022), Delighting in the Trinity: An Introduction to the Christian Faith, InterVarsity Press, ISBN 978-0-8308-4707-5

- Tuggy, Dale (Summer 2014), Trinity (History of Trinitarian Doctrines), http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/trinity/trinity-history.html

- Weedman, Mark (2007). The Trinitarian Theology of Hilary of Poitiers. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004162242.

- Webb, Eugene, In Search of The Triune God: The Christian Paths of East and West (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2014)

External links

- A Formulation and Defense of the Doctrine of the Trinity – A brief historical survey of patristic Trinitarian thought.

- Doctrine of the Trinity Reading Room: Extensive collection of online sources on the Trinity.

- "Trinity". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Trinity". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Trinity". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Trinity". Theopedia.

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Articles containing فرنسية قديمة (842-ح. 1400)-language text

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles incorporating a citation from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- Trinitarianism

- Ancient Christian controversies

- Attributes of God in Christian theology

- Christian terminology

- Triple gods

- God

- لاهوت مسيحي