الأريوسية

الأريوسية أو الأريانية Arianism، هو مذهب مسيحي ظهر في القرن الرابع على يد كاهن مصري من الإسكندرية اسمه أريوس. ونشأت الأريوسية لعدم تفاهم المسيحين والأفكار الكاثوليكية. والطائفة الأريوسية لا تعترف بألهية المسيح بن مريم، ولكنهم يعتقدون أنه انسان، ومنهم من يقول أنه مخلوق وفقط. ومن الطوائف المسيحية التي لقبوا بالأريوسيين: التوحيديون Unitarian، شهود يهوه.

الآريوسية اتخذت اسمها من آريوس، فروّجت تعاليمه من بعده حتى القرن الخامس. واتسع نفوذها بمؤازرة بعض الملوك المسيحيين وبالتئام مجامع محلية لأتباعها. وكانت مدة قرنين تذر قرنها, وهي بين مدٍّ وجزر, بحسب معتقد ونفوذ الملوك آنذاك. فمنهم (قسطنطيوس بن قسطنطين) من ساندوا تعاليمها ودافعوا عن أتباعها ولاحقوا مناوئيها وناصبوهم العداء وبطشوا بهم, ومنهم (ثاوضوسيوس الكبير) من قاوموها ودحضوها ولاحقوا أتباعها. وكانت بدعة آريوس تربة خصبة وممهدة لنشوء البدع اللاحقة, منها «النسطورية» و«المونوفيزية» (أو بدعة الطبيعة الواحدة), وبدعة شهود يهوه في عصرنا.

النشأة

أريوس هو كاهن مسيحي من الإسكندرية، مصر. وُلد أريوس في ليبيا سنة 256، وفي سنة 280، سافر إِلى أنطاكية والتحق بمدرستها الشهيرة، فتتلمذ للمعلم لوقيانوس، «باعث العقلانية الآريوسية، وتدرّب على فن الفصاحة والجدل، وعبّ من معين الفلسفة اليونانية وعلوم اللاهوت، فتخرج وقد فاق معلمه. ثم انتقل إِلى مصر حيث رُسم كاهناً سنة 310، وعُيّن خادماً لإِحدى كنائس الإِسكندرية.[1]

ألمّ آريوس بثقافة فلسفية واسعة ودينية عالية أهّلته لأن يصبح مفكراً عميقا، خطيباً لامعاً، وكاتباً بليغاً ومعلماً في فن الفصاحة والجدل، فنجح في إِشاعة الفكر المسيحي بين عامة الشعب في تعابير ومصطلحات فلسفية، وأدخل إِلى اللاهوت النهج العقلاني مستخدماً في عرض الإِيمان وتفسيره المناهج الفلسفية التي اجتاحت الأوساط المسيحية آنذاك. وبتأثير منه ومن مدرستَي أنطاكية والإسكندرية انتشرت المناقشات والمجادلات الفلسفية بين الأساقفة والكهنة وعامة الشعب، وقد سيطرت على الجميع الرغبة في عرض أسرار الديانة المسيحية عرضاً عقلانياً.

وتجدر الإِشارة إِلى أن آريوس تأثّر بتعاليم الغنوصية (مذهب العرفان الذي ازدهر في القرن الثاني للميلاد في نطاق الكنيسة المسيحية وأكد أصحابه المعرفة الروحية) وبأساطير الإِغريق وتعاليم الديانات الشرقية القديمة، وببدع مسيحية، منها: السابيليانية الغربية (التي تقول بوحدة المسيح مع الآب في الكيان) والشكلانية (أو الحالانية) وهي بدعة المبدأ الواحد (التي تقول إِن الثالوث الأقدس ليس في الواقع إِلا أقنوماً واحداً ظهر للبشرية في أشكال أو أحوال ثلاثة)، والتبنوية (التي تعتقد أن يسوع المسيح ليس سوى إِنسان تبنّاه الله فمنحه سلطة إِلهية).

الاعتقادات

استخدم آريوس مفاهيم الفلسفة البشرية وحدها، فعمد في تفكيره الفلسفي في أمور الدين إِلى الاعتقاد أنه، من بين الأقانيم الثلاثة في الله، الآب وحده هو حقاً وجوهرياً إِله منذ الأزل، أما الابن فليس إِلهاً ولا الروح هو إِله. وزعم أنه كان وقتُ وُجد فيه الآب وحده، واعترف أن الابن هو قبل الدهور، لكنه خليقة وأعظم من كل خليقة مادية وغير مادية. وأضاف أنه قد يصحّ القول عن الابن إِنه إِلهي وفي صوره الآب، ولكن لا يجوز القول إِنه «من جوهر الآب» لأنه مختلف في جوهره عن الآب، والبنوّة في المسيح لا تؤخذ بالمعنى الحقيقي الكياني، بل بالمعنى المجازي الأدبي. فنتج عن هذا الرأي أن المسيح غير مساوٍ للآب, بيد أنه الوسيط بين الآب والخلائق، والوسيط في الخلق، وهو الذي، في لحظة من الأزل خلق الروح القدس. وفي هذا كله اختلق آريوس إِلهاً على صورة البشر.

نشر آريوس آراءه الدينية مستثيراً المناقشات الفلسفية - الدينية العلنية، وقد وجد في النساء العذارى عوناً له, ساعدنه في مهمته، وقد تحمسن له ودافعن عن أفكاره حتى الدم. واستعان آريوس، لترويج مبادئه وتعاليمه، بأساليب كثيرة منها باب الأنغام لمنظومات شعبية وضعها مشبعة بتعاليمه، ينشرها ويرنّم بها الشعب في تطوافات ليلية في ضوء المشاعل. وبسبب تعاليمه المناقضة للإِيمان القويم حرمه مجمع محلّي عُقد في الإسكندرية سنة 320، فالتجأ إِلى نيقوميديا, حيث وضع كتاب الوليمة، وهو مزيج من النثر والشعر والأناشيد الدينية الشعبية. فاتسع نفوذه وراجت تعاليمه في مختلف كنائس الشرق، فانقسم المسيحيون بين مساند له ومناوئ. وكانت لآرائه نتائج خطيرة، في تهدم كل ما أوحى الله به عن حياة الثالوث فيه، وتنكر على الجنس البشري التأله والاتحاد الحقيقي بالله، ولا تعترف للفداء بأي مفعول جذري في الطبيعة البشرية، بل تقر له فقط بتأثير أدبي وروحي.

الأريوسية Homoian

Arianism had several different variants, including Eunomianism and Homoian Arianism. Homoian Arianism is associated with Acacius and Eudoxius. Homoian Arianism avoided the use of the word ousia to describe the relation of Father to Son, and described these as "like" each other.[2] Hanson lists twelve creeds that reflect the Homoian faith:[3]

- The Second Sirmian Creed of 357

- The Creed of Nice (Constantinople) 360

- The creed put forward by Acacius at Seleucia, 359

- The Rule of Faith of Ulfilas

- The creed uttered by Ulfilas on his deathbed, 383

- The creed attributed to Eudoxius

- The Creed of Auxentius of Milan, 364

- The Creed of Germinius professed in correspondence with Ursacius of Singidunum and Valens of Mursa

- Palladius's rule of faith

- Three credal statements found in fragments, subordinating the Son to the Father

الصراع مع الأرثوذكسية

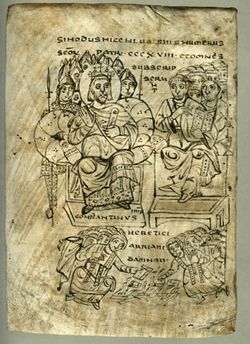

مجمع نيقية الأول

حيال تفاقم التصلب في المواقف الدينية اضطر الملك قسطنطين الكبير إِلى التدخل بحزم. فدعا أساقفة الكنيسة إِلى أول مجمع مسكوني عُقد في مدينة نيقية، فالتأموا من 20 مايو حتى 19 يوليو من سنة 325م، وحددوا أن المسيح من جوهر الآب وأنه واحد في الجوهر، وأقرّوا في الدستور النيقاوي إِيمانهم برب واحد يسوع المسيح، ابن الله الوحيد، المولود من الآب قبل كل الدهور، نور من نور، إِله حق من إِله حق، مولود غير مخلوق، مساوٍ الآب في الجوهر (أو بترجمة أدق واحد مع الآب في الجوهر). وحرم المجمع آريوس وبدعته الهدامة، ثم نفاه الملك قسطنطين، إِلا أنه عاد فعفا عنه بعد بضع سنوات. أما القديس اثناسيوس، رئيس أساقفة الإسكندرية، وركن من أركان مجمع نيقية، وإِمام المدافعين عن الإِيمان القويم ومنشد الكلمة المتجسد وأكبر مناوئ لبدعة آريوس، فقد رفض استقباله في الإسكندرية، فسعى له أتباعه أن يلتحق بأكليروس القسطنطينية. بيد أنه توفي سنة 336 قبل دخوله تلك المدينة.[4]

By 325, the controversy had become significant enough that the Emperor Constantine called an assembly of bishops, the First Council of Nicaea, which condemned Arius's doctrine and formulated the original Nicene Creed of 325.[5] The Nicene Creed's central term, used to describe the relationship between the Father and the Son, is Homoousios (Ancient Greek: ὁμοούσιος),[6][7][8] or Consubstantiality, meaning "of the same substance" or "of one being" (the Athanasian Creed is less often used but is a more overtly anti-Arian statement on the Trinity).[9][10]

The focus of the Council of Nicaea was the nature of the Son of God and his precise relationship to God the Father (see Paul of Samosata and the Synods of Antioch). Arius taught that Jesus Christ was divine/holy and was sent to earth for the salvation of mankind[11] but that Jesus Christ was not equal to God the Father (infinite, primordial origin) in rank and that God the Father and the Son of God were not equal to the Holy Spirit.[12] Under Arianism, Christ was instead not consubstantial with God the Father since both the Father and the Son under Arius were made of "like" essence or being (see homoiousia) but not of the same essence or being (see homoousia).[14]

In the Arian view, God the Father is a deity and is divine and the Son of God is not a deity but divine (I, the LORD, am Deity alone.)[15][11] God the Father sent Jesus to earth for salvation of mankind.[16] Ousia is essence or being, in Eastern Christianity, and is the aspect of God that is completely incomprehensible to mankind and human perception. It is all that subsists by itself and which has not its being in another,[17] God the Father and God the Son and God the Holy Spirit all being uncreated.[أ]

According to the teaching of Arius, the preexistent Logos and thus the incarnate Jesus Christ was a begotten being; only the Son was directly begotten by God the Father, before ages, but was of a distinct, though similar, essence or substance from the Creator. His opponents argued that this would make Jesus less than God and that this was heretical.[13] Much of the distinction between the differing factions was over the phrasing that Christ expressed in the New Testament to express submission to God the Father.[13] The theological term for this submission is kenosis. This ecumenical council declared that Jesus Christ was true God, co-eternal and consubstantial (i.e., of the same substance) with God the Father.[18][ب]

Constantine is believed to have exiled those who refused to accept the Nicaean Creed—Arius himself, the deacon Euzoios, and the Libyan bishops Theonas of Marmarica and Secundus of Ptolemais—and also the bishops who signed the creed but refused to join in condemnation of Arius, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Theognis of Nicaea. The emperor also ordered all copies of the Thalia, the book in which Arius had expressed his teachings, to be burned. However, there is no evidence that his son and ultimate successor, Constantius II, who was a Semi-Arian Christian, was exiled.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Although he was committed to maintaining what the Great Church had defined at Nicaea, Constantine was also bent on pacifying the situation and eventually became more lenient toward those condemned and exiled at the council. First, he allowed Eusebius of Nicomedia, who was a protégé of his sister, and Theognis to return once they had signed an ambiguous statement of faith. The two, and other friends of Arius, worked for Arius's rehabilitation.[20][21][22]

At the First Synod of Tyre in AD 335, they brought accusations against Athanasius, now bishop of Alexandria, the primary opponent of Arius. After this, Constantine had Athanasius banished since he considered him an impediment to reconciliation. In the same year, the Synod of Jerusalem under Constantine's direction readmitted Arius to communion in 336. Arius died on the way to this event in Constantinople. Some scholars suggest that Arius may have been poisoned by his opponents.[20] Eusebius and Theognis remained in the Emperor's favor, and when Constantine, who had been a catechumen much of his adult life, accepted baptism on his deathbed, it was from Eusebius of Nicomedia.[23]

أعقاب نيقيا

The First Council of Nicaea did not end the controversy, as many bishops of the Eastern provinces disputed the homoousios, the central term of the Nicene Creed, as it had been used by Paul of Samosata, who had advocated a monarchianist Christology. Both the man and his teaching, including the term homoousios, had been condemned by the Synods of Antioch in 269.[24] Hence, after Constantine's death in 337, open dispute resumed again. Constantine's son Constantius II, who had become emperor of the eastern part of the Roman Empire, actually encouraged the Arians and set out to reverse the Nicene Creed.[25] His advisor in these affairs was Eusebius of Nicomedia, who had already at the Council of Nicaea been the head of the Arian party, who also was made the bishop of Constantinople.

Constantius used his power to exile bishops adhering to the Nicene Creed, especially St Athanasius of Alexandria, who fled to Rome.[26] In 355 Constantius became the sole Roman emperor and extended his pro-Arian policy toward the western provinces, frequently using force to push through his creed, even exiling Pope Liberius and installing Antipope Felix II.[27]

The Third Council of Sirmium in 357 was the high point of Arianism. The Seventh Arian Confession (Second Sirmium Confession) held that both homoousios (of one substance) and homoiousios (of similar substance) were unbiblical and that the Father is greater than the Son.[28] (This confession was later known as the Blasphemy of Sirmium.)

But since many persons are disturbed by questions concerning what is called in Latin substantia, but in Greek ousia, that is, to make it understood more exactly, as to 'coessential,' or what is called, 'like-in-essence,' there ought to be no mention of any of these at all, nor exposition of them in the Church, for this reason and for this consideration, that in divine Scripture nothing is written about them, and that they are above men's knowledge and above men's understanding;[29]

As debates raged in an attempt to come up with a new formula, three camps evolved among the opponents of the Nicene Creed. The first group mainly opposed the Nicene terminology and preferred the term homoiousios (alike in substance) to the Nicene homoousios, while they rejected Arius and his teaching and accepted the equality and co-eternality of the persons of the Trinity. Because of this centrist position, and despite their rejection of Arius, they were called "Semi-Arians" by their opponents. The second group also avoided invoking the name of Arius, but in large part followed Arius's teachings and, in another attempted compromise wording, described the Son as being like (homoios) the Father. A third group explicitly called upon Arius and described the Son as unlike (anhomoios) the Father. Constantius wavered in his support between the first and the second party, while harshly persecuting the third.

Epiphanius of Salamis labeled the party of Basil of Ancyra in 358 "Semi-Arianism". This is considered unfair by Kelly who states that some members of the group were virtually orthodox from the start but disliked the adjective homoousios while others had moved in that direction after the out-and-out Arians had come into the open.[30]

The debates among these groups resulted in numerous synods, among them the Council of Serdica in 343, the Fourth Council of Sirmium in 358 and the double Council of Rimini and Seleucia in 359, and no fewer than fourteen further creed formulas between 340 and 360, leading the pagan observer Ammianus Marcellinus to comment sarcastically: "The highways were covered with galloping bishops."[31] None of these attempts were acceptable to the defenders of Nicene orthodoxy; writing about the latter councils, Saint Jerome remarked that the world "awoke with a groan to find itself Arian."[32][33]

After Constantius's death in 361, his successor Julian, a devotee of Rome's pagan gods, declared that he would no longer attempt to favor one church faction over another, and allowed all exiled bishops to return; this resulted in further increasing dissension among Nicene Christians. The emperor Valens, however, revived Constantius's policy and supported the "Homoian" party,[34] exiling bishops and often using force. During this persecution many bishops were exiled to the other ends of the Roman Empire (e.g., Saint Hilary of Poitiers to the eastern provinces). These contacts and the common plight subsequently led to a rapprochement between the western supporters of the Nicene Creed and the homoousios and the eastern Semi-Arians.

مجمع القسطنطينية

It was not until the co-reigns of Gratian and Theodosius that Arianism was effectively wiped out among the ruling class and elite of the Eastern Empire. Valens died in the Battle of Adrianople in 378 and was succeeded by Theodosius I, who adhered to the Nicene Creed.[ت] This allowed for settling the dispute. Theodosius's wife St Flacilla was instrumental in his campaign to end Arianism.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Two days after Theodosius arrived in Constantinople, 24 November 380, he expelled the Arian bishop, Demophilus of Constantinople, and surrendered the churches of that city to Gregory of Nazianzus, the Homoiousian leader of the rather small Nicene community there, an act which provoked rioting. Theodosius had just been baptized, by bishop Acholius of Thessalonica, during a severe illness, as was common in the early Christian world. In February he and Gratian had published an edict that all their subjects should profess the faith of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria (i.e., the Nicene faith),[36][37] or be handed over for punishment for not doing so.

Although much of the church hierarchy in the East had opposed the Nicene Creed in the decades leading up to Theodosius's accession, he managed to achieve unity on the basis of the Nicene Creed. In 381, at the Second Ecumenical Council in Constantinople, a group of mainly Eastern bishops assembled and accepted the Nicene Creed of 381,[38] which was supplemented in regard to the Holy Spirit, as well as some other changes: see Comparison of Nicene Creeds of 325 and 381. This is generally considered the end of the dispute about the Trinity and the end of Arianism among the Roman, non-Germanic peoples.[39]

الممالك الجرمانية في أوائل العصور الوسطى

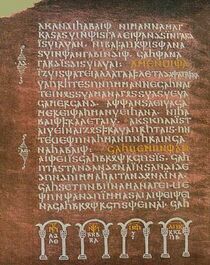

During the time of Arianism's flowering in Constantinople, the Gothic convert and Arian bishop Ulfilas (later the subject of the letter of Auxentius cited above) was sent as a missionary to the Gothic tribes across the Danube, a mission favored for political reasons by the Emperor Constantius II. The Homoians in the Danubian provinces played a major role in the conversion of the Goths to Arianism.[40] Ulfilas's translation of the Bible into Gothic language and his initial success in converting the Goths to Arianism was strengthened by later events; the conversion of Goths led to a widespread diffusion of Arianism among other Germanic tribes as well (Vandals, Langobards, Svevi, and Burgundians).[41] When the Germanic peoples entered the provinces of the Western Roman Empire and began founding their own kingdoms there, most of them were Arian Christians.[41]

The conflict in the 4th century had seen Arian and Nicene factions struggling for control of Western Europe. In contrast, among the Arian German kingdoms established in the collapsing Western Empire in the 5th century were entirely separate Arian and Nicene Churches with parallel hierarchies, each serving different sets of believers. The Germanic elites were Arians, and the Romance majority population was Nicene.[42]

The Arian Germanic tribes were generally tolerant towards Nicene Christians and other religious minorities, including the Jews.[41]

The apparent resurgence of Arianism after Nicaea was more an anti-Nicene reaction exploited by Arian sympathizers than a pro-Arian development.[43] By the end of the 4th century it had surrendered its remaining ground to Trinitarianism. In Western Europe, Arianism, which had been taught by Ulfilas, the Arian missionary to the Germanic tribes, was dominant among the Goths, Langobards and Vandals.[44] By the 8th century, it had ceased to be the tribes' mainstream belief as the tribal rulers gradually came to adopt Nicene orthodoxy. This trend began in 496 with Clovis I of the Franks, then Reccared I of the Visigoths in 587 and Aripert I of the Lombards in 653.[45][46]

The Franks and the Anglo-Saxons were unlike the other Germanic peoples in that they entered the Western Roman Empire as Pagans and were converted to Chalcedonian Christianity, led by their kings, Clovis I of the Franks, and Æthelberht of Kent and others in Britain (see also Christianity in Gaul and Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England).[47] The remaining tribes – the Vandals and the Ostrogoths – did not convert as a people nor did they maintain territorial cohesion. Having been militarily defeated by the armies of Emperor Justinian I, the remnants were dispersed to the fringes of the empire and became lost to history. The Vandalic War of 533–534 dispersed the defeated Vandals.[48] Following their final defeat at the Battle of Mons Lactarius in 553, the Ostrogoths went back north and (re)settled in south Austria.[بحاجة لمصدر]

بقايا في الغرب، القرن 5-7

"Arian" as a polemical epithet

ظهور الأريوسية بعد الإصلاح، القرن 16

نقد

رفض آباء الكنيسة هذا المذهب وذلك في أول مجمع مسكوني في تاريخ المسيحية عام 325 وهو مجمع نيقية حيث صاغوا القسم الأول من قانون الإيمان الذي يقول بإلوهية المسيح وتساويه فيها مع الآب. وحسب تلك العقيدة النيقاوية التي يجب أن يلتزم بها كل مسيحي أن يتبرأ في صلاته من بدعة أريوس. ولاحقا اعتبر آريوس ذاته مهرطقاً. وأعلنوا حرمان آريوس وجميع أتباعه، ولكن هذا لم يوقف انتشار الآريوسية بين مسيحيي ذلك الزمان بعد أن استغلت سياسيا فانتشرت في مصر والشام والعراق وآسيا الصغرى، حتى أصبحت سنة 359 المذهب الرسمي للإمبراطورية الرومانية.[49]

وفي وقت لاحق تفرعت عن هذا المذهب اتجاهات عديدة ، فظهر اتجاه يؤمن بصحة نص قانون الإيمان النيقاوي مع التشكيك بمساواة الابن للآب في الجوهر الإلهي، وسميت هذه الشيعة بأشباه الآريوسيين . وظهر اتجاه آخر يرفض قانون الإيمان النيقاوي رفضا قاطعا على أساس أن طبيعة الابن مختلفة عن تلك التي للآب ، وبرز أيضا اتجاه ثالث يعتقد بأن الروح القدس هو خليقة ثانوية أيضا.

عام 361 م أصبح فالنتس الامبراطور الجديد على العرش الروماني ومع بداية عهده عادت نصاب المسيحية في الإمبراطورية إلى ما كانت عليه من قبل ، فأًعلن أن العقيدة التي أقرها آباء الكنيسة في مجمع نيقية هي العقيدة الرسمية للامبراطورية كلها ، لاحقا عام381 م ثبتت الكنيسة مجددا هذه العقيدة في مجمع القسطنطينية.

مرئيات

| الأسرار الخفية لآريوس ومجمع نيقية. |

انظر أيضا

المصادر

هوامش

|

|

هوامش

- ^ "آريوس والآريوسية". الموسوعة العربية. 9 مايو 2011.

- ^ Hanson 2005, pp. 557–558.

- ^ Hanson 2005, pp. 558–559.

- ^ Löhr, Winrich (23 October 2012). "Arius and Arianism". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. pp. 716–720. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah05025. ISBN 9781444338386.

- ^ The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.vii.iii.html

- ^ Bethune-Baker 2004.

- ^ "Homoousios". Episcopal Church (in الإنجليزية). 2012-05-22. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Farley, Fr Lawrence (23 May 2015). "The Fathers of Nicea: Why Should I Care?". www.oca.org. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "Athanasian Creed | Christian Reformed Church". www.crcna.org (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "The Athanasian Creed by R.C. Sproul". Ligonier Ministries (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةwww-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةritchies.net - ^ أ ب ت ث Pomazansky, Michael (Protopresbyter) (1984). Pravoslavnoye Dogmaticheskoye Bogosloviye [Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A concise exposition] (in الإنجليزية). Translated by Rose, Seraphim (Hieromonk). Platina, California: Saint Herman of Alaska Brotherhood.

- ^ "The oneness of Essence, the Equality of Divinity, and the Equality of Honor of God the Son with the God the Father."[13]

- ^ %2046:9&verse={{{3}}}&src=! Isaiah 46:9 {{{3}}}

- ^ %2017:3&verse={{{3}}}&src=! John 17:3 {{{3}}}

- ^ Lossky 1976, pp. 50–51.

- ^ "Arius and the Nicene Creed | History of Christianity: Ancient". blogs.uoregon.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "3 things Christians should understand about the Nicene-Constantinopolitan creed". Transformed (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2014-01-16. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ أ ب Kirsch 2004.

- ^ Gibbon 1836, Ch. XXI.

- ^ Freeman 2003.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGonzalez 1984 1762 - ^ Chapman 1911.

- ^ Hall, Christopher A. (July 2008). "How Arianism Almost Won". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Reardon, Patrick Henry (8 August 2008). "Athanasius". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Chapman 1910.

- ^ Chapman 1912.

- ^ "Second Creed of Sirmium or 'The Blasphemy of Sirmium'". www.fourthcentury.com. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ^ Kelly 1978, p. 249.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (2019-12-18). The Complete History of the Christian Church (With Bible) (in الإنجليزية). e-artnow.

The pagan Ammianus Marcellinus says of the councils under Constantius: "The highways were covered with galloping bishops;" and even Athanasius rebuked the restless flutter of the clergy.

- ^ "The history of Christianity's greatest controversy". Christian Science Monitor. 1999-09-09. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "On battling Arianism: then and now". Legatus (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Macpherson 1912.

- ^ "Theodosius I". Christian History (in الإنجليزية). 8 August 2008. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Bury, J.B. "History of the Later Roman Empire". penelope.uchicago.edu. University of Chicago. Vol. 1 Chap. XI. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "Sozomen's Church History VII.4". ccel.org.

- ^ The text of this version of the Nicene Creed is available at "The Holy Creed Which the 150 Holy Fathers Set Forth, Which is Consonant with the Holy and Great Synod of Nice". ccel.org. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Arianism | Definition, History, & Controversy | Britannica". www.britannica.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- ^ Szada, Marta (February 2021). "The Missing Link: The Homoian Church in the Danubian Provinces and Its Role in the Conversion of the Goths". Zeitschrift für Antikes Christentum / Journal of Ancient Christianity. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. 24 (3): 549–584. doi:10.1515/zac-2020-0053. eISSN 1612-961X. ISSN 0949-9571. S2CID 231966053.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةJE2 - ^ "7.5: Successor Kingdoms to the Western Roman Empire". Humanities LibreTexts (in الإنجليزية). 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

Most of them were Christians, but, crucially, they were not Catholic Christians, who believed in the doctrine of the Trinity, that God is one God but three distinct persons of the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. They were rather Arians, who believed that Jesus was lesser than God the Father (see Chapter Six). Most of their subjects, however, were Catholics.

- ^ Ferguson 2005, p. 200.

- ^ Fanning, Steven C. (1981-04-01). "Lombard Arianism Reconsidered". Speculum. 56 (2): 241–258. doi:10.2307/2846933. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2846933. S2CID 162786616.

- ^ "Clovis of the Franks | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "Goths and Visigoths". HISTORY (in الإنجليزية). 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Frassetto, Michael, Encyclopedia of barbarian Europe, (ABC-Clio, 2003), p. 128.

- ^ Procopius, Secret Histories, Chapter 11, 18

- ^ الموسوعة العربية المسيحية

وصلات خارجية

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: missing pipe

- CS1 errors: missing name

- أريوسية

- آراء حول يسوع

- جدل مسيحي قديم

- هرطقات في المسيحية

- مصطلحات مسيحية