أسرة يوان

يوان العظمى | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1271–1368 | |||||||||||||||

أسرة يوان في 1294 (گوريو كدولة تابعة) | |||||||||||||||

| المكانة | Khagan-ruled division of the Mongol Empire[note 1] Conquest dynasty of Imperial China | ||||||||||||||

| العاصمة | دادو (بـِيْجينگ المعاصرة)، شانگدو | ||||||||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | الصينية المنغولية Persian[2] | ||||||||||||||

| الدين | البوذية (الصينة والتبتية)، الطاوية، الكونفوشية، الديانة التقليدية الصينية، وكذلك الشامانية/Tengriism، المسيحية (النسطورية)، الإسلام | ||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor[note 2] | |||||||||||||||

• 1260–1294 | قبلاي خان (الأول) | ||||||||||||||

• 1332–1368 | Toghon Temür (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | |||||||||||||||

• 1264–1282 | Ahmad Fanakati | ||||||||||||||

• 1340–1355 | Toqto'a | ||||||||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Post-classical history | ||||||||||||||

• جنكيز خان انتخب امبراطوراً | ربيع 1206 | ||||||||||||||

• Kublai's proclamation of the dynastic name "Great Yuan"[5] | December 18 1271 | ||||||||||||||

| 1268–1273 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 February 1276 | |||||||||||||||

| 19 March 1279 | |||||||||||||||

| 1351–1368 | |||||||||||||||

• سقوط خانباليق | 14 سبتمبر 1368 | ||||||||||||||

• Formation of Northern Yuan dynasty | 1368–1388 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1310[6] | 11,000,000 km2 (4,200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | في الغالب عملة ورقية (چاو)، وكانت تستخدم كميات قليلة من الكاش | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| جزء من سلسلة عن | ||||||||||||||

| تاريخ منغوليا | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| الفترة القديمة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| العصور الوسطى | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| الفترة المعاصرة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| موضوعات | ||||||||||||||

أظهر

القديم | |||

أظهر

الامبراطوري | |||

أظهر

المعاصر | |||

أظهر

مقالات ذات صلة | |||

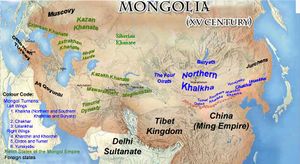

أسرة يوان (Chinese: 元朝; پنين: Yuáncháo; [ɥǎn tʂʰɑ̌ʊ]; بالمنغولية: Dai Ön Ulus/Yekhe Yuan Ulus[7]؛ إنگليزية: Yuan Dynasty) , or Great Yuan Empire (simplified Chinese: 大元帝国; traditional Chinese: 大元帝國; pinyin: Dà Yuán Dìguó) كانت أسرة حاكمة أسسها الزعيم المنغولي قبلاي خان، الذي حكم الصين الحالية، وكل منغوليا الحالية والمناطق المحيطة بها[8] lasting officially from 1271[9] حتى 1368.[10] كانت تعتبر كقسم من امبراطورية المنغول وكأسرة صينية. في التاريخ الصيني، تلت أسرة يوان أسرة سونگ وخلفتها أسرة مينگ. بالرغم من أن الأسرة قد تأسست على يد قبلاي خان، فإن جده الأكبر جنكيز خان قد وضع في السجلات الرسمية على أنه مؤسس الأسرة أو تايزو (Chinese: 太祖). بجانب امبراطور الصين، فقد زعم قبلاي خان أيضاً أنه حامل لقب الخان الأعظم، صاحب السيادة على خانات المنغول الأخرى (خانية چاگاتاي، القبيل الذهبي، إلخانات)؛ ومع ذلك فقد اعترف بهذا الزعم فقط من قبل الإلخانيين، الذين كانوا بالرغم من ذلك يتمتعون بالحكم الذاتي. بالرغم من أن الأباطرة التاليين في أسرة يوان كان معترف بهم من قبل ثلاث إلخانات غربية مستقلة فعلياً على أنهم أصحاب السيادة العليا اسمياً، فقد استمرت كل واحدة من تلك الإلخانات في تقدمها بشكل منفصل. أحياناً يشار إلى يوان على أنها امبراطورية الخان الأعظم، حيث يحمل أباطرة المنغول من أسرة يوان لقب الخان الاعظم لجميع خانات المنغول.[11][12][13]

Although Genghis Khan's enthronement as Khagan in 1206 was described in Chinese as the Han-style title of Emperor[note 2][3] and the Mongol Empire had ruled territories including modern-day northern China for decades, it was not until 1271 that Kublai Khan officially proclaimed the dynasty in the traditional Han style,[14] and the conquest was not complete until 1279 when the Southern Song dynasty was defeated in the Battle of Yamen. His realm was, by this point, isolated from the other Mongol-led khanates and controlled most of modern-day China and its surrounding areas, including modern-day Mongolia.[15] It was the first dynasty founded by a non-Han ethnicity that ruled all of China proper.[16][17] In 1368, following the defeat of the Yuan forces by the Ming dynasty, the Genghisid rulers retreated to the Mongolian Plateau and continued to rule until 1635 when they surrendered to the Later Jin dynasty (which later evolved into the Qing dynasty). The rump state is known in historiography as the Northern Yuan.

After the division of the Mongol Empire, the Yuan dynasty was the khanate ruled by the successors of Möngke. In official Chinese histories, the Yuan dynasty bore the Mandate of Heaven. The dynasty was established by Kublai Khan, yet he placed his grandfather Genghis Khan on the imperial records as the official founder of the dynasty and accorded him the temple name Taizu.[note 2] In the edict titled Proclamation of the Dynastic Name issued in 1271,[5] Kublai announced the name of the new dynasty as Great Yuan and claimed the succession of former Chinese dynasties from the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors to the Tang dynasty.[5] Some of the Yuan emperors mastered the Chinese language, while others only used their native Mongolian language, written with the ʼPhags-pa script.[18]

Kublai, as a Khagan (Great Khan) of the Mongol Empire from 1260, had claimed supremacy over the other successor Mongol khanates: the Chagatai, the Golden Horde, and the Ilkhanate, before proclaiming as the Emperor of China in 1271. As such, the Yuan was also sometimes referred to as the Empire of the Great Khan. However, even though the claim of supremacy by the Yuan emperors was recognized by the western khans in 1304, their subservience was nominal and each continued its own separate development.[19][20][صفحة مطلوبة]

الاسم

| أسرة يوان | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Yuan dynasty" in Chinese characters (top) and "Great Yuan State" (Yehe Yüan Ulus, a modern form) in Mongolian script (bottom) | |||

| الصينية | 元朝 | ||

| المعنى الحرفي | "Yuan dynasty" | ||

| |||

| Dynastic name | |||

| الصينية | 大元 | ||

| المعنى الحرفي | Great Yuan | ||

| |||

| Alternative official full name: ᠳᠠᠢ ᠶᠤᠸᠠᠨ ᠶᠡᠬᠡ ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ ᠤᠯᠤᠰ Dai Yuwan Yeqe Mongɣul Ulus | |||

| الصينية التقليدية | 大元大蒙古國 | ||

| الصينية المبسطة | 大元大蒙古国 | ||

| المعنى الحرفي | "Great Yuan" (Middle Mongol transliteration of Chinese "Dà Yuán") Great Mongol State | ||

| |||

In 1271, Kublai Khan imposed the name Great Yuan (Chinese: 大元; pinyin: Dà Yuán), establishing the Yuan dynasty.[21] "Dà Yuán" (大元) is derived from a clause "大哉乾元" (dà zāi Qián Yuán; 'Great is Qián', 'the Primal') in the Commentaries on the I Ching section[22] regarding the first hexagram (乾).[5] The Mongolian-language counterpart was Dai Ön Ulus, also rendered as Ikh Yuan Üls or Yekhe Yuan Ulus. In Mongolian, Dai Ön a borrowing from Chinese, was often used in conjunction with the "Yeke Mongghul Ulus" (大蒙古國; 'Great Mongol State'), which resulted in the form ᠳᠠᠢ

ᠥᠨ

ᠶᠡᠬᠡ

ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ

ᠤᠯᠤᠰ (大元大蒙古國; Dai Ön Yeqe Mongɣul Ulus, lit. "Great Yuan – Great Mongol State")[7] or ᠳᠠᠢ ᠦᠨ

ᠺᠡᠮᠡᠺᠦ

ᠶᠡᠬᠡ

ᠮᠣᠩᠭᠣᠯ

ᠤᠯᠤᠰ (Dai Ön qemeqü Yeqe Mongɣol Ulus, lit. "Great Mongol State called Great Yuan").[23][24][25]

As per contemporary historiographical norm, "Yuan dynasty" typically refers to the realm with its main capital in Dadu (modern-day Beijing). However, the Han-style dynastic name "Great Yuan" and the claim to Chinese political orthodoxy were meant for the entire Mongol Empire when the dynasty was proclaimed.[5][26] This usage is seen in the writings, including non-Chinese texts, produced during the time of the Yuan dynasty.[26] In spite of this, "Yuan dynasty" is not commonly used in the broad sense of the definition by modern scholars due to the division of the Mongol Empire. Some scholars believe that 1260 was the year that the Yuan dynasty emerged with the proclamation of a reign title following the collapse of the unified Mongol Empire.[27]

The Yuan dynasty is sometimes also called the "Mongol dynasty" by westerners,[28] akin to the Qing dynasty sometimes being referred to as the "Manchu dynasty"[29] or "Manchu Dynasty of China".[30] Furthermore, the Yuan is sometimes known as the "Empire of the Great Khan" or "Khanate of the Great Khan",[31] since Yuan emperors held the nominal title of Great Khan; these appeared on some Yuan maps. However, both terms can also refer to the khanate within the Mongol Empire directly ruled by Great Khans before the actual establishment of the Yuan dynasty by Kublai Khan in 1271.

التاريخ

قالب:Campaignbox Mongol conquests

Background

Genghis Khan united the Mongol tribes of the steppes and became Great Khan in 1206.[32] He and his successors expanded the Mongol empire across Asia. Under the reign of Genghis' third son, Ögedei Khan, the Mongols destroyed the weakened Jin dynasty in 1234, conquering most of northern China.[33] Ögedei offered his nephew Kublai a position in Xingzhou, Hebei. Kublai was unable to read Chinese but had several Han teachers attached to him since his early years by his mother Sorghaghtani. He sought the counsel of Chinese Buddhist and Confucian advisers.[34] Möngke Khan succeeded Ögedei's son, Güyük, as Great Khan in 1251.[35] He granted his brother Kublai control over Mongol held territories in China.[36] Kublai built schools for Confucian scholars, issued paper money, revived Chinese rituals, and endorsed policies that stimulated agricultural and commercial growth.[37] He adopted as his capital city Kaiping in Inner Mongolia, later renamed Shangdu.[38]

Many Han Chinese and Khitan defected to the Mongols to fight against the Jin. Two Han Chinese leaders, Shi Tianze, Liu Heima (劉黑馬, aka Liu Ni),[39] and the Khitan Xiao Zhala (蕭札剌) defected and commanded the 3 Tumens in the Mongol army. Liu Heima and Shi Tianze served Ögedei Khan.[40] Liu Heima and Shi Tianxiang led armies against Western Xia for the Mongols.[41] There were 4 Han Tumens and 3 Khitan Tumens, with each Tumen consisting of 10,000 troops. The three Khitan Generals Shimobeidier (石抹孛迭兒), Tabuyir (塔不已兒), and Zhongxi, the son of Xiaozhaci (蕭札刺之子重喜) commanded the three Khitan Tumens and the four Han Generals Zhang Rou, Yan Shi, Shi Tianze, and Liu Heima commanded the four Han tumens under Ögedei Khan.[42][43]

Möngke Khan commenced a military campaign against the Chinese Song dynasty in southern China.[44] The Mongol force that invaded southern China was far greater than the force they sent to invade the Middle East in 1256.[45] He died in 1259 without a successor at the Siege of Diaoyucheng.[46] Kublai returned from fighting the Song in 1260 when he learned that his brother, Ariq Böke, was challenging his claim to the throne.[47] Kublai convened a kurultai in Kaiping that elected him Great Khan.[48] A rival kurultai in Mongolia proclaimed Ariq Böke Great Khan, beginning a civil war.[49] Kublai depended on the cooperation of his Chinese subjects to ensure that his army received ample resources. He bolstered his popularity among his subjects by modeling his government on the bureaucracy of traditional Chinese dynasties and adopting the Chinese era name of Zhongtong.[50] Ariq Böke was hampered by inadequate supplies and surrendered in 1264.[51] All of the three western khanates (Golden Horde, Chagatai Khanate and Ilkhanate) became functionally autonomous, and only the Ilkhans truly recognized Kublai as Great Khan.[52][53] Civil strife had permanently divided the Mongol Empire.[54]

Rule of Kublai Khan

Early years

Instability troubled the early years of Kublai Khan's reign. Ögedei's grandson Kaidu refused to submit to Kublai and threatened the western frontier of Kublai's domain.[55][56] The hostile but weakened Song dynasty remained an obstacle in the south.[55] Kublai secured the northeast border in 1259 by installing the hostage prince Wonjong as the ruler of the Kingdom of Goryeo (Korea), making it a Mongol tributary state.[57][55] Kublai betrothed one of his daughters to the prince to solidify the relationship between the two houses.[58] Korean women were sent to the Yuan court as tribute and one concubine became the empress of the Yuan dynasty.[59] Kublai was also threatened by domestic unrest. Li Tan, the son-in-law of a powerful official, instigated a revolt against Mongol rule in 1262. After successfully suppressing the revolt, Kublai curbed the influence of the Han advisers in his court.[60] He feared that his dependence on Chinese officials left him vulnerable to future revolts and defections to the Song.[61]

Kublai's government after 1262 was a compromise between preserving Mongol interests in China and satisfying the demands of his Chinese subjects.[62] He instituted the reforms proposed by his Chinese advisers by centralizing the bureaucracy, expanding the circulation of paper money, and maintaining the traditional monopolies on salt and iron.[63] He restored the Imperial Secretariat and left the local administrative structure of past Chinese dynasties unchanged.[64] However, Kublai rejected plans to revive the Confucian imperial examinations and divided Yuan society into three classes with the Han occupying the lowest rank until the conquest of the Song dynasty and its people, who made up the fourth class, the Southern Chinese. Kublai's Chinese advisers still wielded significant power in the government, sometimes more than high officials, but their official rank was nebulous.[63]

تأسيس الأسرة

Kublai readied the move of the Mongol capital from Karakorum in Mongolia to Khanbaliq in 1264,[65] constructing a new city near the former Jurchen capital Zhongdu, now modern Beijing, in 1266.[66] In 1271, Kublai formally claimed the Mandate of Heaven and declared that 1272 was the first year of the Great Yuan (大元) in the style of a traditional Chinese dynasty.[67] The name of the dynasty is first attested in the I Ching and describes the "origin of the universe" or a "primal force".[68] Kublai proclaimed Khanbaliq the Daidu (大都; Dàdū; 'Great Capital') of the dynasty.[69] The era name was changed to Zhiyuan to herald a new era of Chinese history.[70] The adoption of a dynastic name legitimized Mongol rule by integrating the government into the narrative of traditional Chinese political succession.[71] Kublai evoked his public image as a sage emperor by following the rituals of Confucian propriety and ancestor veneration,[72] while simultaneously retaining his roots as a leader from the steppes.[71]

Kublai Khan promoted commercial, scientific, and cultural growth. He supported the merchants of the Silk Road trade network by protecting the Mongol postal system, constructing infrastructure, providing loans that financed trade caravans, and encouraging the circulation of paper jiaochao banknotes. During the beginning of the Yuan dynasty, the Mongols continued issuing coins; however, under Külüg Khan coins were completely replaced by paper money. It was not until the reign of Toghon Temür that the government of the Yuan dynasty would attempt to reintroduce copper coinage for circulation.[73] The Pax Mongolica, Mongol peace, enabled the spread of technologies, commodities, and culture between China and the West.[74] Kublai expanded the Grand Canal from southern China to Daidu in the north.[75] Mongol rule was cosmopolitan under Kublai Khan.[76] He welcomed foreign visitors to his court, such as the Venetian merchant Marco Polo, who wrote the most influential European account of Yuan China.[77] Marco Polo's travels would later inspire many others like Christopher Columbus to chart a passage to the Far East in search of its legendary wealth.[78]

Military conquests and campaigns

After strengthening his government in northern China, Kublai pursued an expansionist policy in line with the tradition of Mongol and Chinese imperialism. He renewed a massive drive against the Song dynasty to the south.[80] Kublai besieged Xiangyang (襄阳) between 1268 and 1273,[81] the last obstacle in his way to capture the rich Yangtze River basin.[65] An unsuccessful naval expedition was undertaken against Japan in 1274.[82] The Duan family ruling the Kingdom of Dali (大理) in Yunnan submitted to the Yuan dynasty as vassals and were allowed to keep their throne, militarily assisting the Yuan dynasty against the Song dynasty in southern China.

The Duan family still ruled Dali relatively independently during the Yuan dynasty.[83] The Tusi chieftains and local tribe leaders and kingdoms in Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan submitted to Yuan rule and were allowed to keep their titles. The Han Chinese Yang family ruling the Chiefdom of Bozhou, which was recognized by both the Song and Tang dynasty, also received recognition by the Mongols in the Yuan dynasty, and later by the Ming dynasty. The Luo clan in Shuixi led by Ahua were recognized by the Yuan emperors, as they were by the Song emperors when led by Pugui and Tang emperors when led by Apei. They descended from the Three Kingdoms era king Huoji who legendarily helped Zhuge Liang against Meng Huo.[84] They were also recognized by the Ming dynasty.[85]

In 1276 Kublai captured the Song capital of Hangzhou (杭州), the wealthiest city of China,[86] after the surrender of the Southern Song Han Chinese Emperor Gong of Song.[87] Emperor Gong was married off to a Mongol princess of the royal Borjigin family of the Yuan dynasty.[88] Song loyalists escaped from the capital and enthroned a young child as Emperor Bing of Song, who was Emperor Gong's younger brother. The Yuan forces commanded by Han Chinese General Zhang Hongfan led a predominantly Han navy to defeat the Song loyalists at the battle of Yamen in 1279. The last Song emperor drowned, bringing an end to the Song dynasty.[89] The conquest of the Song reunited northern and southern China for the first time in three hundred years.[90]

The Yuan dynasty created the "Han Army" (漢軍) out of defected Jin troops and an army of defected Song troops called the "Newly Submitted Army" (新附軍).[91]

Kublai's government faced financial difficulties after 1279. Wars and construction projects had drained the Mongol treasury.[92] Efforts to raise and collect tax revenues were plagued by corruption and political scandals.[93] Mishandled military expeditions followed the financial problems.[92] Kublai's second invasion of Japan in 1281 failed because of an inauspicious typhoon.[82] Kublai botched his campaigns against Annam, Champa, and Java,[94] but won a Pyrrhic victory against Burma.[95] The expeditions were hampered by disease, an inhospitable climate, and a tropical terrain unsuitable for the mounted warfare of the Mongols.[94][82] The Trần dynasty which ruled Annam (Đại Việt) defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288). Annam, Burma, and Champa recognized Mongol hegemony and established tributary relations with the Yuan dynasty.[96]

Internal strife threatened Kublai within his empire. Kublai Khan suppressed rebellions challenging his rule in Tibet and the northeast.[97] His favorite wife died in 1281 and so did his chosen heir in 1285. Kublai grew despondent and retreated from his duties as emperor. He fell ill in 1293, and died on 18 February 1294.[98]

Successors after Kublai

Temür Khan

Following the conquest of Dali in 1253, the former ruling Duan family were appointed as its leaders.[99] Local chieftains were appointed as Tusi, recognized as imperial officials by the Yuan, Ming, and Qing-era governments, principally in the province of Yunnan. Succession for the Yuan dynasty, however, was an intractable problem, later causing much strife and internal struggle. This emerged as early as the end of Kublai's reign. Kublai originally named his eldest son, Zhenjin, as the crown prince, but he died before Kublai in 1285.[100] Thus, Zhenjin's third son, with the support of his mother Kökejin and the minister Bayan, succeeded the throne and ruled as Temür Khan, or Emperor Chengzong, from 1294 to 1307. Temür Khan decided to maintain and continue much of the work begun by his grandfather. He also made peace with the western Mongol khanates as well as neighboring countries such as Vietnam,[101] which recognized his nominal suzerainty and paid tributes for a few decades. However, the corruption in the Yuan dynasty began during the reign of Temür Khan.

Külüg Khan

Külüg Khan (Emperor Wuzong) came to the throne after the death of Temür Khan. Unlike his predecessor, he did not continue Kublai's work, largely rejecting his objectives. Most significantly he introduced a policy called "New Deals", focused on monetary reforms. During his short reign (1307–11), the government fell into financial difficulties, partly due to bad decisions made by Külüg. By the time he died, China was in severe debt and the Yuan court faced popular discontent.[16]

Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan

The fourth Yuan emperor, Buyantu Khan (born Ayurbarwada), was a competent emperor. He was the first Yuan emperor to actively support and adopt mainstream Chinese culture after the reign of Kublai, to the discontent of some Mongol elite.[102] He had been mentored by Li Meng (李孟), a Confucian academic. He made many reforms, including the liquidation of the Department of State Affairs (尚書省), which resulted in the execution of five of the highest-ranking officials.[102] Starting in 1313 the traditional imperial examinations were reintroduced for prospective officials, testing their knowledge on significant historical works. Also, he codified much of the law, as well as publishing or translating a number of Chinese books and works.

Gegeen Khan and Yesün Temür

Emperor Gegeen Khan, Ayurbarwada's son and successor, ruled for only two years, from 1321 to 1323. He continued his father's policies to reform the government based on the Confucian principles, with the help of his newly appointed grand chancellor Baiju. During his reign, the Da Yuan Tong Zhi (《大元通制》; 'Comprehensive Institutions of the Great Yuan'), a huge collection of codes and regulations of the Yuan dynasty begun by his father, was formally promulgated. Gegeen was assassinated in a coup involving five princes from a rival faction, perhaps steppe elite opposed to Confucian reforms. They placed Yesün Temür (or Taidingdi) on the throne, and, after an unsuccessful attempt to calm the princes, he also succumbed to regicide.

Before Yesün Temür's reign, China had been relatively free from popular rebellions after the reign of Kublai. Yuan control, however, began to break down in those regions inhabited by ethnic minorities. The occurrence of these revolts and the subsequent suppression aggravated the financial difficulties of the Yuan government. The government had to adopt some measure to increase revenue, such as selling offices, as well as curtailing its spending on some items.[103]

Jayaatu Khan Tugh Temür

When Yesün Temür died in Shangdu in 1328, Tugh Temür was recalled to Khanbaliq by the Qipchaq commander El Temür. He was installed as emperor in Khanbaliq, while Yesün Temür's son Ragibagh succeeded to the throne in Shangdu (商都) with the support of Yesün Temür's favorite retainer Dawlat Shah. Gaining support from princes and officers in Northern China and some other parts of the dynasty, Khanbaliq-based Tugh Temür eventually won the civil war against Ragibagh known as the War of the Two Capitals. Afterwards, Tugh Temür abdicated in favour of his brother Kusala, who was backed by Chagatai Khan Eljigidey, and announced Khanbaliq's intent to welcome him. However, Kusala suddenly died only four days after a banquet with Tugh Temür. He was supposedly killed with poison by El Temür, and Tugh Temür then remounted the throne. Tugh Temür also managed to send delegates to the western Mongol khanates such as Golden Horde and Ilkhanate to be accepted as the suzerain of Mongol world.[104] However, he was mainly a puppet of the powerful official El Temür during his latter three-year reign. El Temür purged pro-Kusala officials and brought power to warlords, whose despotic rule clearly marked the decline of the dynasty.

Due to the fact that the bureaucracy was dominated by El Temür, Tugh Temür is known for his cultural contribution instead. He adopted many measures honoring Confucianism and promoting Chinese cultural values. His most concrete effort to patronize Chinese learning was founding the Academy of the Pavilion of the Star of Literature (奎章閣學士院), first established in the spring of 1329 and designed to undertake "a number of tasks relating to the transmission of Confucian high culture to the Mongolian imperial establishment" (儒教推崇). The academy was responsible for compiling and publishing a number of books, but its most important achievement was its compilation of a vast institutional compendium named Jingshi Dadian (經世大典). Tugh Temür supported Zhu Xi's Neo-Confucianism and also devoted himself in Buddhism.

Toghon Temür

After the death of Tugh Temür in 1332 and subsequent death of Rinchinbal (Emperor Ningzong) the same year, the 13-year-old Toghon Temür (Emperor Huizong), the last of the nine successors of Kublai Khan, was summoned back from Guangxi and succeeded to the throne. After El Temür's death, Bayan became as powerful an official as El Temür had been in the beginning of his long reign. As Toghon Temür grew, he came to disapprove of Bayan's autocratic rule. In 1340 he allied himself with Bayan's nephew Toqto'a, who was in discord with Bayan, and banished Bayan by coup. With the dismissal of Bayan, Toqto'a seized the power of the court. His first administration clearly exhibited fresh new spirit. He also gave a few early signs of a new and positive direction in central government. One of his successful projects was to finish the long-stalled official histories of the Liao, Jin, and Song dynasties, which were eventually completed in 1345. Yet, Toqto'a resigned his office with the approval of Toghon Temür, marking the end of his first administration, and he was not called back until 1349.

Decline of the empire

The final years of the Yuan dynasty were marked by struggle, famine, and bitterness among the populace. In time, Kublai Khan's successors lost all influence on other Mongol lands across Asia, while the Mongols beyond the Middle Kingdom saw them as too Chinese. Gradually, they lost influence in China as well. The reigns of the later Yuan emperors were short and marked by intrigues and rivalries. Uninterested in administration, they were separated from both the army and the populace, and China was torn by dissension and unrest. Outlaws ravaged the country without interference from the weakening Yuan armies.

From the late 1340s onwards, people in the countryside suffered from frequent natural disasters such as droughts, floods and the resulting famines, and the government's lack of effective policy led to a loss of popular support. In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion led by Song loyalists started and grew into a nationwide uprising and the Song loyalists established a renewed Song dynasty in 1351 with its capital at Kaifeng. In 1354, when Toghtogha led a large army to crush the Red Turban rebels, Toghon Temür suddenly dismissed him for fear of betrayal. This resulted in Toghon Temür's restoration of power on the one hand and a rapid weakening of the central government on the other. He had no choice but to rely on local warlords' military power, and gradually lost his interest in politics and ceased to intervene in political struggles. He fled north to Shangdu from Khanbaliq (present-day Beijing) in 1368 after the approach of the forces of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), founded by Zhu Yuanzhang in the south. Zhu Yuanzhang was a former Duke and commander in the army of the Red Turban Song dynasty and assumed power as Emperor after the death of the Red Turban Song Emperor Han Lin'er, who had tried to regain Khanbaliq, which eventually failed, and who died in Yingchang (located in present-day Inner Mongolia) two years later (1370). Yingchang was seized by the Ming shortly after his death. Some royal family members still live in Henan today.[105][ذو صلة؟]

The Prince of Liang, Basalawarmi established a separate pocket of resistance to the Ming in Yunnan and Guizhou, but his forces were decisively defeated by the Ming in 1381. By 1387 the remaining Yuan forces in Manchuria under Naghachu had also surrendered to the Ming dynasty. The Yuan remnants retreated to Mongolia after the fall of Yingchang to the Ming in 1370, where the name Great Yuan (大元) was formally carried on, and is known as the Northern Yuan dynasty.

يوان الشمالية

مقالة مفصلة: يوان الشمالية

مقالة مفصلة: يوان الشمالية

الوقع

كان هناك تنوع ثقافي غني في عهد أسرة يوان. تمثلت الانجازات الثقافية الهامة في تطور الدراما والرواية والاستخدام المتزايد للكتابة بالعامية. الوحدة السياسية للصين والتجارة الرائجة بين الشرق الغرب في معظم آسيا الوسطى. الاتصالات الموسعة للمنغول بين غرب ىسيا واوروپا أنتج قدر كبير من التبادل الثقافي. الثقافات والشعوب الأخرى في امبراطورية المنغول كان متأثرة بشكل كبير أيضاً بالصين. سهلت بشكل كبير التجارة عبر آسيا حتى فترة تراجعها؛ الاتصالات بين أسرة يوان وحلفيها وتابعها في فارس، شجعت إلخانات على التطور.[106][107] كان للبوذية تأثير كبير على حكومة يوان، البوذية التانترية التبتية كان لها تأثير كبير على الصين في تلك الفترة. مسلمو أسرة يوان أدخلوا علم الخرائط، علم الفلك، الطب، الملابس والنظام الغذائي الشرق أوسطي إلى شرق آسيا. الحاصلات الشرق أوسطية مثل الجزر، اللفت، وأنواع جديدة من الليمون والباذنجان، والبطيخ، والسكر عالي الجودة، والقطن جميعها أدخلت أو انتشرت بنجاح في عهد أسرة يوان.[15]

الألات الموسيقية الغربية أدخلت لإثراء الفنون الصينية التطبيقية الصينية. يعود لتلك الفترة الدخول إلى الإسلام، والذي حدث بواسطة مسلمي آسيا الوسطى، إلى أعداد متزايدة من الصينيين في شمال غرب وجنوب غرب البلاد. النسطورية الجديدة والرومانية الكاثوليكية أيضاً تمتعت بفترة من التسامح. البوذية (خاصة البوذية التبتية) انتعشت في تلك الفترة، بالرغم من أن الطاوية عانت من الاضطهاد لصالح البوذية من قبل حكومة يوان. الممارسات والخبرات الحكومية الكونفوشية كانت معتمدة على الكلاسيكيات، والتي كان معمولاً بها في شمال الصين أثناء فترة الانقسام، والتي أعادها بلاط اليوان، ربماً أملاً في المحافظة على مجتمع الهان. حدث تقدم في مجالات أدب الرحلات، رسم الخرائط، الجغرافيا والتعليم العلمي.

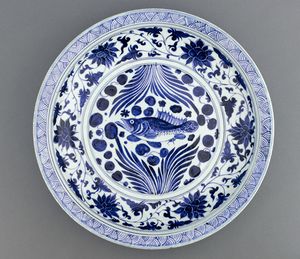

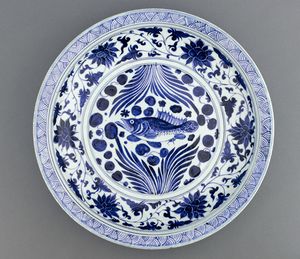

بعذ الابتكارات والمنتجات الصينية، مثل الملح الصخري، تقنيات الطباعة، الخزف الصيني، أوراق اللعب والأدب الطبي، تم تصديرها لاوروپا وغرب آسيا، بينما أصبح انتاج الزجاج الرقيق والكلوازون منتشراً في الصين. امبراطور مينگ ژو يوانژانگ (1368–97) كان معجباً بتوحيد المنغول للصين وتبنى نظام حاميتها.[15]

أول رحلات مسجلة قام بها اوروپيون للصين ترجع إلى ذلك الوقت. أشهر رحالة في تلك الفترة كان ماركو پولو البندقي، الذي قام برحلة إلى "كامبالوك"، عاصمة الخان الأعظم، وأثارت حياته هناك دهشة الشعب الاوروپي. تقرير رحلاته Il milione (أو، المليون، اشتهر بالإنگليزية باسم رحلات ماركو پولو)، ظهرت حوالي عام 1299. يجادل البعض حول دقة تقارير ماركو پولو بسبب إفتقادها الإشارة إلى سور الصين العظيم، بيوت الشاي، والتي كان معلماً بارزاً من منذ تبني الاوروپيين ثقافة الشاي، وكذلك practice of foot binding من قبل النساء في عاصمة الخان الاعظم. يقترح البعض أن ماركو پولو حصل على معظم معلوماته عن طريق الاتصال بالتجار الفرس حيث أن الكثير من الأماكن كانت تحمل الأسماء الفارسية.[109]

قامت أسرة يوان بالأعمال العامة الموسعة. الاتصالات البرية والمائية أعيد تنظيمها وتطورت. لمكافحة أي مجاعة المحتملة، تم بناء الصوامع على إمتداد الامبراطورية. مدينة بكين أعيد بناؤها وشيد قصر جديد يضم بحيرات صناعية، تلال وجبال، ومنتزهات. في عهد أسرة يوان، أصبحت بكين المحطة الأخيرة لقناة الصين العظيمة، والتي تم تجديدها بالكامل. هذه التحسينات التجارية شجهت التجارة البرية والبحرية في آسيا ويسرت الاتصالات الصينية المباشرة مع اوروپا. الرحالة الصينيون إلى الغرب كان يمكنهم تقديم المساحلة في مثل تلك المناطق مثل الهندسة الهديروليكية. الاتصالات مع الغرب أدت إلى إدخال المحصول الغذائي الرئيسي إلى الصين، الذرة الرفيعة، إلى جانب المنتجات الغذائية الأجنبية وطرق الطهي.

أسرة يوان (1271-1368) كانت أول أسرة من أصول غير صينية تحكم عموم الصين. في تأريخ منغوليا، كانت تعتبر بصفة عامة استمرار لامبراطورية المنغول.[110]اشتهر المنغول بعبادة السماء الخالدة، وحسب الأيديولوجيا المنغولية التقليدية تعتبر يوان "بداية عدد لا حصر له من المخلوقات، أساس السلام والسعادة، سلطة الدولة، حلم الكثير من الناس، بالإضافة إلى أنه ليس هناك شيء كبير أو الثمينة" كان قد غزا الصين بأكمله.[111] من جهة أخرى، في التأريخ الصيني التقليدي عادة ما تعتبر أسرة يوان الأسرة الشرعية بين أسرة سونگ وأسرة مينگ.[112] مع ملاحظة، أن أسرة يوان تقليدياً كانت ممتدة لتشمل امبراطورية المنغول قبل تأسيس قبلاي خان الرسمي ليوان عام 1271، إلى حد ما لأن قبلاي كان جده الأكبر جنكيز خان قد وضع في السجل الرسمي على أنه مؤسس الأسرة أو تايزو (Chinese: 太祖). بالرغم من أن التأريخ التقليدي وكذلك الآراء الرسمية (تشمل حكومة [[أسرة مينگ) التي أطاحت بأسرة يوان)، هناك شعوب صينية لا تعتبر أسرة يوان أسرة شرعية في الصين، لكن تعتبر حكمها فترة هيمنة أجنبية. يعتقد هؤلاء أن صينيو هان كانوا يعاملون كمواطنين من الدرجة الثانية، وأن الصين شهدت فترة ركود اقتصادي وعلمي؛ وكذلك، التكنولوجيات الصينية مثل البارود والبوصلة انتشرت إلى اوروپا في عهد أسرة يوان. لكن هناك أيضاً آراء أخرى.

الحكومة

المجتمع

أسلوب الحياة الإمبراطوري

الطبقات الاجتماعية

سياسياً، نظام الحكومة الذي أسسه قبلاي خان كان نظام وسط بين الاقطاع التراثي المنغولي والنظام الاوتوقراطي-البيروقراطي الصيني التقليدي. ومع ذلك، فمن الناحية الاجتاعية فالنخبة الصينية المتعلمة بصفة عامة لم تحظ بنفس التقدير الذي كانت تحظى به في عهد الأسرات الصينية الأصلية. بالرغم من أن النخب الصينية التقليدية لم تكن تحظى بنصيب من السلطة، فالمنغول والسومويون (جماعات متحالفة مختلفة من آسيا الوسطى والطرف الغربي للامبراطورية) كانوا لا يزالون غرباء إلى حد كبير على التيار الثقافي الصيني، وأعطى هذا الانقسام نظام يوان صبغة "استعمارية".[113] ربما بسبب الخوف من انتقال السلطة إلى العرقية الصينية في عهدهم، عامل المنغول الصينيين بعدم مساواة. منحوا المزايا للمنغول والسوميين حتى بعد عودة الاختبار الامبراطوري في القرن 14. بصفة عامة لم يصل الصينيون الشماليون أو الجنوبيون إلى المناصب العليا في الحكومة مقارنة بالفرس في إلخانات.[114] فيما بعد، استجابة للاعتراضات على استخدام "البربر" في حكومته، رد امبراطور مينگ يونگل قائلاً: "... كان التمييز يستخدم من قبل المنغول في في عهد أسرة يوان، الذين كانوا يوظفون فقط "المنغول والتتار" ويستبعدون الصينيين الشماليين والجنوبيين وكان هذا هو ما تسبب في وقوع الكارثة لهم". [115] المؤرخ المنغولي، چولووني دالاي، اعترف بأن الحملات العسكرية المنغولية اللانهائية (خاصة في الفترة الأولى من حكمهم) تسببت في أعباء مالية واجتماعية-اقتصادية على الصينين، الكوريين والجماعات العرقية الأخرى تحت حكمهم.

وظفت الامبراطورية المنغولية الكثير من الأجانب على مدار تاريخها. قبلاي أدخل التسلسل الهرمي عن طريق تقسيم السكان في أسرة يوان إلى الطبقات التالية:

- المنغول

- السمويون، ويشملون الأويغور، المهاجرون من الغرب وبعض العشائر من آسيا الوسطى.

- الصينيون الشمالية، الخيتان، الجورچن، والكوريون.

- الجنوبيون، أو جميع المنتمين لأسرة سونگ السابقة.

التجار الشركاء أو المشرفون من غير المنغول عادة ما كانوا إما مهاجرين أو جماعات عرقية محلية. بالتالي، فقد كان في الصين المسلمين الاويغور، التركمان، والفرس، والمسيحييين. الأجانب من خارج الامبراطورية المنغولية، مثل عائلة پولو، كانوا محل ترحيب في كل مكان.

وبالرغم من المكانة المرموقة المعطاة للمسلمين، إلا أن بعض سياسات أباطرة يوان ميزت بشدة ضدهم، وحدت من الذبح الحلال والممارسات الإسلامية الأخرى مثل الختان، وذلك الذبح الكوشر لليهود، مما أجبرهم على أكل الطعام على الطريقة المنغولية.[116] وهي في طريقها للنهاية، أصبح الفساد والاضطهاد شديد جداً حيث انضم الجنرالات المسلمون إلى الهان الصينيين في تمردهم ضد المنغول. ژو يوانژانگ مؤسس مينگ كان لديهم جنرالات مسلمين مثل لان يو الذي تمرد ضد المنغول وهزمهم في القتال. بعد التجمعات المسلمة كان لها اسم في الصينية يعني "البركات" أو "الشكر"، يزعم الكثير من مسلمي هوي أن السبب في ذلك يرجع إلى أنهم لعبوا دوراً هاماً في الإطاحة بالمنغول وأطلق عليهم هذا الاسم تقديراً لهم من الهان الصينيين على مساعدتهم إياهم.[117]

في المتاجر

ازدهرت الصناعة في تلك الأيام ازدهاراً لم ير له مثيل في كافة أنحاء الأرض قبل القرن الثامن عشر. فمهما تتبعنا تاريخ الصين إلى ماضيه السحيق وجدنا الحرف اليدوية منتشرة في البيوت والتجارة رائجة في المدن.

أنشئت في أيام قبلاي خان طرق عامة رصفت بالحجارة ولكنها لم يبق منها الآن إلا جوانبها. أما شوارع المدن فلم تكن سوى أزقة لا يزيد عرضها على ثمان أقدام صممت لكي تحجب الشمس، وكانت القناطر كثيرة العدد جميلة في بعض الأحيان، ومن أمثلتها القنطرة الرخامية التي كانت عند القصر الصيفي، وكان التجار والمسافرون يستخدمون الطرق المائية بقدر ما كانوا يستخدمون الطرق البرية، وكان في البلاد قنوات مائية يبلغ طولها 25,000 ميل، ولم يكن في الأعمال الهندسية الصينية ما يفوق القناة الكبرى التي تربط هانجتشاو بتيانشين والتي يبلغ طولها 650 ميلاً، والتي بُدئ في حفرها سنة 300 م وتم في عهد كوبلاي خان، لم يكن يفوقها إلا السور العظيم. وكانت القوارب المختلفة الأشكال والأحجام لا ينقطع غدوها ورواحها في الأنهار، ولم تكن تتخذ وسائل للنقل الرخيص فحسب بل كانت تتخذ كذلك مساكن للملايين من الأهلين الفقراء.

والصينيون تجار بطبعهم وهم يقضون عدة ساعات في المساومات التجارية، وكان الفلاسفة الصينيون والموظفون الصينيون متفقين على احتقار التجار، وقد فرض عليهم أباطرة أسرة هان ضرائب فادحة وحرموا عليهم الانتقال بالعربات ولبس الحرير.

وكان أفراد الطبقات الراقية يطيلون أظافرهم ليدلوا بعملهم هذا على أنهم لا يقومون بأعمال جثمانية، كما تطيل النساء الغربيات أظافر أيديهن لهذا الغرض عينه(64)، وقد جرت العادة أن يعد العلماء والمدرسون والموظفون من الطبقات الراقية، وتليهم في هذا طبقة الزراع، ويأتي الصناع في المرتبة الثالثة، وكانت أوطأ الطبقات طبقة التجار لأن هذه الطبقة الأخيرة- على حد قول الصينيين- لا تجني الأرباح إلا بتبادل منتجات غيرها من الناس.

لكن التجار مع ذلك آثروا ونقلوا غلاّت حقول الصين وسلع متاجرها إلى جميع أطراف آسية، وصاروا في آخر الأمر الدعامة المالية للحكومة الصينية. وكانت التجارة الداخلية تعرقلها الضرائب الفادحة، وأما التجارة الخارجية فكانت معرضة لهجمات قُطّاع الطريق في البر والقرصان في البحر. ومع هذا فقد استطاع التجار الصينيون أن ينقلوا بضائعهم إلى الهند وفارس وبلاد النهرين ورومة نفسها في آخر الأمر بالطواف حول شبه جزيرة الملايو بحراً وبالسير في طرق القوافل التي تخترق التركستان(55). وكانت أشهر الصادرات هي الحرير والشاي والخوخ والمشمش والبارود وورق اللعب، وكان العالم يرسل إلى الصين بدل هذه الغلات والبضائع الفِصْفِصَة والزجاج والجزر والفول السوداني والدخان والأفيون.

وكان من أسباب تيسير التبادل التجاري نظام الائتمان والنقود. فقد كان التجار يقرض بعضهم بعضاً بفوائد عالية تبلغ في العادة نحو 36%، ونقول إنها عالية وإن لم تكن أعلى مما كانت في بلاد اليونان والرومان(65). وكان من أسباب ارتفاع سعر الفائدة ما يتعرض له المرابون من أخطار شديدة، فكانوا من أجل ذلك يتقاضون من الأرباح ما يتناسب مع هذه الأخطار، ولم يكن أحد يحبهم إلا في مواسم الاستدانة. ومن الحكم الصينية المأثورة قولهم: "السارقون بالجملة ينشئون المصارف"(57). وأقدم ما عرف من النقود ما كان يتخذ من الأصداف البحرية والمدي والحرير.

ويقول ماركو بولو عن خزائن كوبلاي خان: "إن دار السك الإمبراطورية تقوم في مدينة كمبلوك (پكين)، وأنت إذا شاهدت الطريقة التي تصدر بها النقود قلت إن فن الكيمياء أتقن أتقاناً لا إتقان بعده، وكنت صادقاً فيما تقول. ذلك أنه يصنع نقوده بالطريقة الآتية"، ثم أخذ يستثير سخرية مواطنيه وتشككهم فيما يقول وعدم تصديقهم إياه فوصف الطريقة التي يؤخذ بها لحاء شجر التوت فتصنع منه قطع من الورق يقبلها الشعب ويعدها في مقام الذهب(60). ذلك هو منشأ السيل الجارف من النقود الورقية الذي أخذ من ذلك الحين يدفع عجلة الحياة الاقتصادية في العالم مسرعة تارة ويهدد هذه الحياة بالخراب تارة أخرى.

المخترعات والعلوم

لقد كان الصينيون أقدر على الاختراع منهم على الانتفاع بما يخترعون. فقد اخترعوا البارود في أيام أسرة تانج، ولكنهم قصروا استعماله وقتئذ على الألعاب النارية، وكانوا في ذلك جد عقلاء؛ ولم يستخدموه في صنع القنابل اليدوية وفي الحروب إلا في عهد أسرة سونج (عام 1161م). وعرف العرب ملح البارود (نترات البوتاسيوم)- وهو أهم مركبات البارود- في أثناء اتجارهم مع الصين وسموه "الثلج الصيني" ونقلوا سر صناعة البارود إلى البلاد الغربية، واستخدمه العرب في أسبانيا في الأغراض الحربية، ولعل سير روجر بيكون أول من ذكره من الأوربيين قد عرفه من دراسته لعلوم العرب أو من اتصاله بده- برو كي الرحالة الذي طاف في أواسط آسية.

الرياضيات

وقد خلف عالمها الرياضي المعمر جانج تسانج (المتوفى في عام 152ق.م) وراءه كتاباً في الجبر والهندسة فيه أول إشارة معروفة للكميات السالبة. وقد حسب دزو تسو تشونج- جي القيمة الصحيحة للنسبة التقريبية إلى ثلاثة أرقام عشرية، وحسن المغنطيس أو "الأداة التي تشير إلى الجنوب"، وقد وردت إشارة عنه غير واضحة قيل فيها إنه كان يجري التجارب على سفينة تتحرك بنفسها(68).

واخترع تشانج هنج آلة لتسجيل الزلازل (سيزموغرافيا) في عام 132م . ولكن علم الطبيعة الصيني قد ضلت معظم أبحاثه في دياجير الفنج جوي السحرية واليانج والين من أبحاث ما وراء الطبيعة . وأكبر الظن أن علماء الرياضة الصينيين قد أخذوا الجبر عن علماء الهند، ولكنهم هم الذين أنشئوا علم الهندسة في بلادهم مدفوعين إلى هذا بحاجتهم إلى قياس الأرض(70). وكان في وسع الفلكيين في أيام كنفوشيوس أن يتنبئوا بالخسوف والكسوف تنبؤاً دقيقاً، وأن يضعوا أساس التقويم الصيني بتقسيم اليوم إلى اثنتي عشرة ساعة وتقسيم السنة إلى اثني عشر شهراً يبدأ كل منها بظهور الهلال، وكانوا يضيفون شهراً آخر في كل بضع سنين لكي يتفق التقويم القمري مع الفصول الشمسية(71). وكانت حياة الصينيين على الأرض تتفق والحياة في السماء؛ وكانت أعياد السنة تحددها منازل الشمس والقمر، بل إن نظام المجتمع من الناحية الأخلاقية كان يقوم على منازل الكواكب السيارة والنجوم.

الطب

وكان الطب في الصين خليطاً من الحكمة التجريبية والخرافات الشعبية. وكانت بدايته فيما قبل التاريخ المدون، ونبغ فيه أطباء عظماء قبل عهد أبقراط بزمن طويل، وكانت الدولة من أيام أسرة جو تعقد امتحانا سنوياً للذين يريدون الاشتغال بالمهن الطبية، وتحدد مرتبات الناجحين منهم في الامتحان حسب ما يظهرون من جدارة في الاختبارات. وقد أمر حاكم صيني في القرن الرابع قبل المسيح أن تشرح جثث أربعين من المجرمين المحكوم عليهم بإعدامهم، وأن تدرس أجسامهم دراسة تشريحية، ولكن نتائج هذا التشريح وهذه الدراسة قد ضاعت وسط النقاش النظري، ولم تستمر عمليات التشريح فيما بعد. وكتب جانج جونج- تنج في القرن الثاني عدة رسائل في التغذية والحميات ظلت هي النصوص المعمول بها مدى ألف عام، وكتب هوا- دو في القرن الثالث كتاباً في الجراحة، وأشاع العمليات الجراحية باختراع نبيذ يخدر المريض تخديراً تاماً. ومن سخافات التاريخ أن ضاعت أوصاف هذا المخدر فيما بعد، ولم يعرف عنها شيء. وكتب وانج شو-هو في عام 300 بعد الميلاد رسالة ذائعة الصيت عن ضربات القلب(72).

وفي أوائل القرن السادس كتب داو هونج- جنج وصفاً شاملاً لسبعمائة وثلاثين عقاراً مما كان يستخدم في الأدوية الصينية، وبعد مائة عام من ذلك الوقت كتب جاو يوان- فانج كتاباً قيماً في أمراض النساء والأطفال ظل من المراجع الهامة زمناً طويلاً. وكثرت دوائر المعارف الطبية في أيام أباطرة أسرة تانج كما كثرت الرسائل الطبية المتخصصة التي تبحث كل منها في موضوع واحد في عهد الملوك من أسرة سونج(73). وأنشئت في أيام هذه الأسرة كلية طبية؛ وإن ظل طريق التعليم الطبي هو التمرين والممارسة. وكانت العقاقير الطبية كثيرة متنوعة حتى لقد كان أحد مخازن الأدوية منذ ثلاثمائة عام يبيع منها بنحو ألف ريال في اليوم الواحد(74). وكان الأطباء يطنبون ويتحذلقون في تشخيص الأمراض، فقد وصفوا من الحميات مثلاً ألف نوع، وميزوا من أنواع النبض أربعاً وعشرين حالة. واستخدموا اللقاح في معالجة الجدري، وإن كانوا لم يستخدموا التطعيم للوقاية منه، ولعلهم قد أخذوا هذا عن الهند، ووصفوا الزئبق للعلاج من الزهري. ويلوح أن هذا المرض الأخير قد ظهر في الصين في أواخر أيام أسرة منج وأنه انتشر انتشاراً مروعاً بين الأهلين، وأنه بعد زواله قد خلف وراءه حصانة نسبية تقيهم أشد عواقبه خطورة. غير أن الإجراءات الصحية العامة والأدوية الواقية، والقوانين الصحية لم تتقدم تقدماً يذكر في بلاد الصين؛ كما كان نظام المجاري والمصارف نظاماً بدائياً إذا كان قد وضع لهما نظام على الإطلاق(75). وقد عجزت بعض المدن عن حل أول الواجبات المفروضة على كل مجتمع منظم- ضمان ماء الشرب النقي والتخلص من الفضلات.

وكان الصابون من مواد الترف التي لا يحصل عليها إلا الأثرياء الممتازون، وإن كان القمل وغيره من الحشرات كثير الانتشار. وقد اعتاد الصيني الساذج أن يهرش جسمه ويخدشه وهو مطمئن هادئ هدوء الكنفوشيين. ولم يتقدم علم الطب تقدماً يستحق الذكر من أيام شي هوانج-دي إلى أيام الملكة الوالدة. ولعل في وسعنا أن نقول هذا القول بعينه من علم الطب في أوربا من عهد أبقراط إلى عهد باستير. وغزا الطب الأوربي بلاد الصين في صحبة المسيحية ولكن المرضى الصينيين من الطبقات الدنيا ظلوا إلى أيامنا هذه يقصرون الانتفاع به على الجراحة. أما فيما عداها فهم يفضلون أطباءهم وأعشابهم القديمة على الأطباء الأوربيين والعقاقير الأوربية.

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة أباطرة أسرة يوان

- الامبراطورية المنغولية

- شجرة عائلة أسرة يوان

- أسرة جين (金朝)

- أسرة سونگ

- أسرة منگ

- شيا الغربية

- تاريخ منغوليا

- قائمة الخانات المنغول

- Jun ware

- الغزوات المنغولية

- الاوروپيون في الصين في العصور الوسطى

- الإسلام أثناء أسرة يوان

- Hua-Yi distinction

ملاحظات

^ a: http://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E4%BA%BA%E5%8F%A3%E5%8F%B2#.E5.85.83

^ b: http://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E4%BA%BA%E5%8F%A3%E5%8F%B2#.E5.85.83

الهامش

- ^ Koh, Walter, ed. (2014). "China under Mongol Rule: The Yuan dynasty" (PDF). China Symposium.

- ^ Ralph Kauz (2010). Ralph Kauz (ed.). Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 89. ISBN 3447061030. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ أ ب Song, Lian (1976) [1370]. "太祖本紀 [Chronicle of Taizu]". 元史 [History of Yuan] (in Literary Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. 元年丙寅,帝大會諸王群臣,建九游白纛,即皇帝位於斡難河之源。諸王群臣共上尊號曰成吉思皇帝。 [In [1206], on the bingyin day, the emperor greatly assembled the many princes and numerous vassals, and erected his nine-tailed white tuğ banner, assuming the position of Emperor of China at the source of the Onon river. And the many princes and numerous vassals together bestowed upon him the reverent title Genghis Huangdi.]

- ^ Yang Fuxue (杨富学) (1997). 回鹘文献所见蒙古"合罕"称号之使用范围 [The scope of use of Mongolian "Khagan" title found in Old Uyghur literature]. 内蒙古社会科学 [Inner Mongolia Social Sciences]. Gansu Dunhuang Research Institute (5). S2CID 224535800.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Kublai Emperor (18 December 1271) (in zh-Classical), 《元典章》[Statutes of Yuan], http://zh.wikisource.org/wiki/建國號詔

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia" (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 499. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ أ ب حسب بعض المصادر مثل "Volker Rybatzki, Igor de Rachewiltz-The early mongols: language, culture and history, p.116", the full Mongolian name is "Dai Ön Yeke Mongghul Ulus". خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "mname" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Christopher P.Atwood – Encyclopedia of منغوليا والامبراطورية المنغولية

- ^ تأسست يوان رسمياً في هذه السنة. ومع ذلك فلم تكن قد سيطرت بعد على عموم جنوب الصين حتى عام 1279، عندما تم سحق آخر مقاومة لسونگ الجنوبية.

- ^ استمرت بقايا يوان تحكم [[منغوليا] بعد عام 1368، عندما كانت تعرف بيوان الشمالية.

- ^ Micheal Prwadin – The Mongol Empire and its legacy

- ^ J.J.Saunders – The history of Mongol conquests

- ^ Rene Grousset – The Empire of Steppes

- ^ Mote 1994, p. 624.

- ^ أ ب ت Atwood, Christopher Pratt (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Mongol Empire p.611" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب San, Tan Koon (2014). Dynastic China: An Elementary History. Kuala Lumpur: The Other Press. pp. 312, 323. ISBN 978-983-9541-88-5. OCLC 898313910.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram (1971). A History of China (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 232. ISBN 0-520-01518-5.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Franke, Herbert (1953). "Could the Mongol emperors read and write Chinese?" (PDF). Asia Major. Second series. Academica Sinica. 3 (1): 28–41.

- ^ Saunders, John Joseph (2001) [1971]. The History of the Mongol Conquests. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-8122-1766-7.

- ^ Grousset, René (1939). L'empire des steppes: Attila, Gengis-Khan, Tamerlan [The Empire of Steppes] (in الفرنسية).

- ^ Simon, Karla W. (26 April 2013). Civil Society in China: The Legal Framework from Ancient Times to the 'New Reform Era'. Oxford University Press. p. 39 n. 69. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199765898.003.0002. ISBN 9780190297640.

- ^ . 《易傳》 [Commentaries on the I Ching] (in الصينية التقليدية).

《彖》曰:大哉乾元,萬物資始,乃統天。

- ^ 陈得芝 (2009). "关于元朝的国号、年代与疆域问题". 北方民族大学学报. 87 (3).

- ^ Hodong Kim (2015). "Was 'da Yuan' a Chinese Dynasty?". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 45: 288.

- ^ Francis Woodman Cleaves (1949). "The Sino-Mongolian Inscription of 1362 in Memory of Prince Hindu". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 12: 8.

- ^ أ ب Robinson, David (2019). In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-108-48244-8.Robinson, David (2009). Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols. Harvard–Yenching Institute Monograph Series 68 Studies in East Asian Law. Brill. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-674-03608-6.Hodong Kim (2018). "Mongol Perceptions of "China" and the Yuan Dynasty". In Brook, Timothy; Walt van Praag, Michael van; Boltjes, Miek (eds.). Sacred Mandates: Asian International Relations since Chinggis Khan. University of Chicago Press. pp. 45–56. ISBN 978-0-226-56293-3. At p. 45.

- ^ Hodong Kim (2015). "Was 'da Yuan' a Chinese Dynasty?". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 45: 279–280. doi:10.1353/sys.2015.0007.

- ^ William Honeychurch; Chunag Amartuvshin (2006). "States on Horseback: The Rise of Inner Asian Confederations and Empires". In Miriam T. Stark (ed.). Archaeology of Asia. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 255–278. doi:10.1002/9780470774670.ch12. ISBN 9780470774670.

- ^ Piero Corradini (1962). "Civil Administration at the Beginning of the Manchu Dynasty: A note on the establishment of the Six Ministries (Liu-pu)". Oriens Extremus. Harrassowitz Verlag. 9 (2): 133–138. JSTOR 43382329.

- ^ Elizabeth E. Bacon (September 1971). "Reviewed Work: Central Asia. Gavin Hambly". American Journal of Sociology (book review). University of Chicago Press. 77 (2): 364–366. doi:10.1086/225131. JSTOR 2776897.

- ^ Ronald Findlay; Mats Lundahl (2006). "The First Globalization Episode: The Creation of the Mongol Empire, or the Economics of Chinggis Khan". In Göran Therborn; Habibul Khondker (eds.). Asia and Europe in Globalization. Brill. pp. 13–54. doi:10.1163/9789047410812_005. ISBN 9789047410812.

- ^ Ebrey 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Ebrey 2010, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 415.

- ^ Allsen 1994, p. 392.

- ^ Allsen 1994, p. 394.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 418.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 65.

- ^ قالب:Cite periodical

- ^ Françoise Aubin (1987). "The Rebirth of Chinese Rule in Times of Trouble". In Schram, Stuart Reynolds (ed.). Foundations and Limits of State Power in China. pp. 113–146. ISBN 978-0-7286-0139-0.

- ^ Ruth Dunnell (1989). "The Fall of the Xia Empire: Sino-Steppe Relations in the Late 12th – Early 13th Centuries". In Seaman, Gary; Marks, Daniel (eds.). Rulers from the Steppe: State Formation on the Eurasian periphery. Ethnographics Monograph Series No. 2. University of Southern California Press. pp. 158–185. ISBN 1-878986-01-5. Proceedings of the Soviet-American Academic Symposia "Nomads: Masters of the Eurasian Steppe".

- ^ Hu Xiaopeng (胡小鹏) (2001). 窝阔台汗己丑年汉军万户萧札剌考辨——兼论金元之际的汉地七万户 [A Study of Xiao Zhala the Han Army commander of 10,000 families in the jichou Year of 1229 during the Period of Ögedei Khan – with a discursus on the Han territory of 70,000 families at the Northern Jin–Yuan boundary]. Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Sciences) (in الصينية المبسطة) (6): 36–42. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-9162.2001.06.008.

- ^ Ke Shaomin (1920). "Volume 146: Biographies #43". New History of Yuan.

- ^ Allsen 1994, p. 410.

- ^ John Masson Smith Jr. (1998). "Nomads on Ponies vs. Slaves on Horses. Reviewed Work: Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Īlkhānid War, 1260–1281 by Reuven Amitai-Preiss". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 54–62. JSTOR 606298.

- ^ Allsen 1994, p. 411.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 422.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 51.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 53.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 423–424.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 62.

- ^ Allsen 1994, p. 413.

- ^ Allsen 2001, p. 24.

- ^ أ ب ت Rossabi 1988, p. 77.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 105.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, pp. 438.

- ^ Lorge, Peter (2010). "Review of David M. Robinson, Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia under the Mongols. Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series". China Review International. 17 (3): 377–379. ISSN 1069-5834. JSTOR 23733178.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 426.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 66.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 427.

- ^ أ ب Rossabi 1988, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 70.

- ^ أ ب Ebrey 2010, p. 172.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 132.

- ^ Mote 1994, p. 616.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 136.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 461.

- ^ Mote 1999, p. 458.

- ^ أ ب Mote 1999, p. 616.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 458.

- ^ David Miles; Andrew Scott (2005). Macroeconomics: Understanding the Wealth of Nations. John Wiley & Sons. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-470-01243-7.Mike Markowitz (22 May 2016). "Coinage of the Mongols". CoinWeek. Ancient Coin Series. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016.Hartill, David (2005). Cast Chinese Coins: A Historical Catalogue. Trafford. ISBN 1-4120-5466-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[صفحة مطلوبة] - ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 72.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 463.

- ^ Allsen 2001, p. 61.

- ^ "Panel VI". The Cresques Project. Catalan Atlas.Cavallo, Jo Ann (2013). The World Beyond Europe in the Romance Epics of Boiardo and Ariosto. University of Toronto Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4426-6667-2.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 429.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 77.

- ^ أ ب ت Morgan 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Michael C. Brose (2014). "Yunnan's Muslim Heritage". In Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 3 Southeast Asia, Volume: 22. Brill. pp. 135–155. doi:10.1163/9789004282483_006. ISBN 978-90-04-28248-3.

- ^ Herman, John. E. (2005). "The Mu'ege kingdom: A brief history of a frontier empire in Southwest China". In Di Cosmo, Nicola; Wyatt, Don J (eds.). Political Frontiers, Ethnic Boundaries and Human Geographies in Chinese History. Routledge. pp. 245–285. ISBN 978-1-135-79095-0.

- ^ John E. Herman (2006). "The Cant of Conquest: Tusi Offices and China's Political Incorporation of the Southwest Frontier". In Crossley, Pamela Kyle; Siu, Helen F.; Sutton, Donald S. (eds.). Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China. Vol. 28 of Studies on China. University of California Press. pp. 135–170. ISBN 978-0-520-23015-6.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 430.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 106.

- ^ Hua, Kaiqi (2018). "The Journey of Zhao Xian and the Exile of Royal Descendants in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1358)". In Heirman, Ann; Meinert, Carmen; Anderl, Christoph (eds.). Buddhist Encounters and Identities Across East Asia. Leiden: Brill. pp. 196–226. doi:10.1163/9789004366152_008. ISBN 978-90-04-36615-2.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Morgan 2007, p. 113.

- ^ Charles O. Hucker (1985). A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8047-1193-7. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ^ أ ب Rossabi 1994, p. 473.

- ^ Rossabi 2012, p. 111.

- ^ أ ب Rossabi 2012, p. 113.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, p. 218.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Rossabi 1988, pp. 487–488.

- ^ Rossabi 1994, p. 488.

- ^ Stone, Zofia (2017). Genghis Khan: a Biography. New Delhi: Vij Books India. ISBN 978-93-86367-11-2. OCLC 975222159.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Craughwell, Thomas J. (2010). The Rise and Fall of the Second Largest Empire in History: How Genghis Khan's Mongols almost Conquered the World. Beverly, MA: Fair Winds Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-61673-851-8. OCLC 777020257.

- ^ Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2. OCLC 779849477.

- ^ أ ب Powers, John; Templeman, David (2012). "Yuan Dynasty". Historical Dictionary of Tibet. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 742. ISBN 978-0-8108-7984-3. OCLC 801440529.

- ^ Hsiao 1994, p. 551.

- ^ Hsiao 1994, p. 550.

- ^ 成吉思汗直系后裔现身河南 巨幅家谱为证 [Genghis Khan's direct descendants still alive in Henan: huge pedigree chart verifies]. 今日安报 (in الصينية). 6 February 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008.

- ^ Gregory G.Guzman - Were the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?, The historian 50 (1988), 568-70

- ^ Thomas T.Allsen - Culture and conquest in Mongol Eurasia, 211

- ^ Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art: A Guide to the Collection. London: Giles. p. 28. ISBN 9781904832775. Retrieved 2011-07-01.

- ^ Frances, Wood. "Did Marco Polo Go to China (London: Secker & Warburg, 1995)

- ^ The Mongol Empire By Michael Prawdin, Gerard Chaliand, ISBN 9781412805193

- ^ Ganbold et al., op. cit., 2006, p.20–21.

- ^ Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties (960–1911)

- ^ Ed. Herbert Franke, Denis Twitchett, John King Fairbank-The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907-1368, p. 491-492

- ^ David Morgan-Who Ran the Mongol Empire?, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1 (1982), p.135

- ^ David Morgan-Who Ran the Mongol Empire?, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No. 1 (1982), pp.124-136

- ^ Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims" (PDF). The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. p. 12. Retrieved 30 November 2010..

- ^ Dru C. Gladney (1991). Muslim Chinese: ethnic nationalism in the People's Republic (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University. p. 234. ISBN 0674594959. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- J. J. Saunders, The History of the Mongol Conquests (1971)

- Ahmad Y. al-Hassan and Donald R. Hill, Islamic Technology (1988)

للاستزادة

- Chan Hok-lam and de Bary, W.T., Yuan Thought: Chinese Thought and Religion Under the Mongols, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982). ISBN 978-0231053242.

- Cotterell, Arthur. (2007). The Imperial Capitals of China - An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. London: Pimlico. pp. 304 pages. ISBN 9781845950095.

- Langlois, John D., China Under Mongol Rule, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981). ISBN 978-0691101101.

- Paludan, Ann. (1998). Chronicle of tasdasadtaehe China Emperors. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 224 pages. ISBN 0-500-05090-2.

- Rossabi, M., Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989). ISBN 978-0520067400.

وصلات خارجية

| هذه المقالة تحتوي على نصوص بالصينية. بدون دعم الإظهار المناسب, فقد ترى علامات استفهام ومربعات أو رموز أخرى بدلاً من الحروف الصينية. |

| سبقه أسرة سونگ |

الأسر في التاريخ الصيني 1271-1368 |

تبعه أسرة منگ |

| أظهر الامبراطورية المنغولية |

|---|

39°54′N 116°23′E / 39.900°N 116.383°E

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "note"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="note"/>

- CS1 uses الصينية-language script (zh)

- CS1 foreign language sources (ISO 639-2)

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from July 2023

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 الصينية التقليدية-language sources (zh-hant)

- CS1 الصينية المبسطة-language sources (zh-hans)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 الصينية-language sources (zh)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing منغولية-language text

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles that may have off-topic sections

- Wikipedia articles that may have off-topic sections from July 2023

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- انحلالات 1368

- تاريخ منغوليا

- الامبراطورية المنغولية

- أسرة يوان

- بلدان سابقة في شرق آسيا

- بورجيگين

- دول ومناطق تأسست في 1271