الإسلام والپروتستانتية

| پروتستانتية |

هوسيون • Lollards • Waldensians

تجديدية العماد • Anglicanism • كالڤينية • Counter-Reformation • لوثرية • Polish Brethren • Remonstrants • زوينگلية

الكنيسة المعمدانية • Congregationalists • Pietism • پيوريتانية • Moravian • Methodism • Universalism • Mennonites • آميش • Free Presbyterianism Pentecostalism • Revivalism • Evangelicalism • House church movement

Philippine Independent Church • الكنيسة الكاثوليكية الرسولية • United Seventh-Day Brethren |

| الإسلام والأديان الأخرى |

|---|

|

| الديانات الابراهيمية |

| أديان غير ابراهيمية |

| موضوعات أخرى |

| قوالب - بوابة |

Protestantism and Islam entered into contact during the early-16th century when the Ottoman Empire, expanding in the Balkans, first encountered Calvinist Protestants in present-day Hungary and Transylvania. As both parties opposed the Austrian Holy Roman Emperor and his Roman Catholic allies, numerous exchanges occurred, exploring religious similarities and the possibility of trade and military alliances.

The early Protestants and Turks established a sense of mutual tolerance and understanding, despite theological differences on Christology, considering each other to be closer to one another than to Catholicism.[1] The Ottoman Empire supported the early Protestant churches and contributed to their survival in dire times. Martin Luther regarded the Ottomans as allies against the papacy, considering them the "rod of God's wrath against Europe's sins."[2] The allegiances of the Ottoman Empire and threat of Ottoman expansion in Eastern Europe pressured King Charles V to sign the Peace of Nuremberg with the Protestant princes, accept the Peace of Passau, and the Peace of Augsburg, formally recognizing Protestantism in Germany and ending military threats to their existence.[3]

خلفية تاريخية

Protestantism and Islam entered into contact during the 16th century when Calvinist Protestants in present-day Hungary and Transylvania coincided with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans. As Protestantism is divided into a few distinguishable branches and multiple denominations within the former, it is hard to determine the relations specifically. Many of these denominations can have a different approachment to this matter. Islam is divided as well into various denominations. This article focuses on Protestant-Muslim relations, but should be taken with caution.

Relations became more adversarial in the early modern and modern periods, although recent attempts have been made at rapprochement. In terms of comparative religion, there are interesting similarities especially with the Sunni, while Catholics are often noted for similarities with Shias,[4][5][6][7][8][9] as well as differences, in both religious approaches.

Following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed the Conqueror and the unification of the Middle East under Selim I and his son Suleiman the Magnificent managed to expand Ottoman rule into Central Europe. The Habsburg Empire thus entered into direct conflict with the Ottomans.

At the same time the Protestant Reformation was taking place in numerous areas of northern and central Europe, in harsh opposition to Papal authority and the Holy Roman Empire led by Emperor Charles V. This situation led the Protestants to consider various forms of cooperation and rapprochement (religious, commercial, military) with the Muslim world, in opposition to their common Habsburg enemy.

مواءمات دينية مبكرة (القرون 15–17)

During the development of the Reformation, Protestantism and Islam were considered closer to each other than they were to Catholicism: "Islam was seen as closer to Protestantism in banning images from places of worship, in not treating marriage as a sacrament and in rejecting monastic orders".[1]

تسامح متبادل

The Sultan of the Ottoman Empire was known for his tolerance of the Christian and Jewish faiths within his dominions, whereas the King of Spain did not tolerate the Protestant faith.[10] The Ottoman Empire was indeed known at that time for its religious tolerance. Various religious refugees, such as the Huguenots, some Anglicans, Quakers, Anabaptists or even Jesuits or Capuchins were able to find refuge at Istanbul and in the Ottoman Empire,[11] where they were given right of residence and worship.[12] Further, the Ottomans supported the Calvinists in Transylvania and Hungary but also in France.[11] The contemporary French thinker Jean Bodin wrote:[11]

The great emperor of the Turks does with as great devotion as any prince in the world honour and observe the religion by him received from his ancestors, and yet detests he not the strange religions of others; but on the contrary permits every man to live according to his conscience: yes, and that more is, near unto his palace at Pera, suffers four diverse religions viz. that of the Jews, that of the Christians, that of the Grecians, and that of the Mahometans.

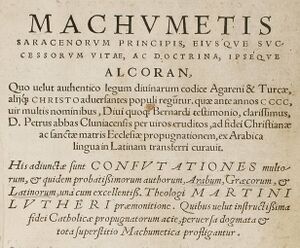

Martin Luther, in his 1528 pamphlet, On War against the Turk, calls for the Germans to resist the Ottoman invasion of Europe, as the catastrophic Siege of Vienna was lurking, but expressed views of Islam which, compared to his aggressive speech against Catholicism (and later Judaism), are relatively mild.[13] Concerned with his personal preaching on divine atonement and Christian justification, he extensively criticized the principles of Islam as utterly despicable and blasphemous, considering Qu'ran as void of any tract of divine truth. For Luther, it was mandatory to let the Qu'ran "speak for itself" as means to show what Christianity saw as a draft from prophetic and apostolic teaching, therefore allowing a proper Christian response. His knowledge on the subject was based on a medieval polemicist version of the Qu'ran made by Riccoldo da Monte di Croce, which was the European scholarly reference of the subject. In 1542, while Luther was translating Riccoldo's Refutation of the Koran, which would become the first version of Koranic material in German, he wrote a letter to Basle's city council to relieve the ban on Theodore Bibliander's translation of the Qu'ran into Latin. Mostly due to his letter, Bibliander's translation was finally allowed and eventually published in 1543, with a preface made by Martin Luther himself. With access to a more accurate translation of the Qu'ran, Luther understood some of Riccoldo's critiques to be partial, but nevertheless concurred with virtually all of them.[14]

As a religious profession, however, Luther felt the same sense of tolerance for freedom of conscience to be given to Islam as to other faiths of its time:

Let the Turk believe and live as he will, just as one lets the papacy and other false Christians live.

— Excerpt from On war against the Turk, 1529.[15]

However, this statement mentions "Turks", and it is not clear whether the meaning was of "Turks" as a representation of the specific rule of the Ottoman Empire, or as a representation of Islam in general.

Martin Luther's reasoning also appears in one of his other comments, in which he said that "A smart Turk makes a better ruler than a dumb Christian".[16]

جهود التقارب العقائدي

الثورة الهولندية والإسلام

Fundamentally, the Protestant Dutch had strong antagonisms to both the Catholics and the Muslims. In some cases however, alliances, or attempts at alliance between the Dutch and the Muslims were made possible, as when the Dutch allied with the Muslims of the Moluccas to oust the Portuguese,[17] and the Dutch became rather tolerant of the Islamic religion in their colonial possessions after the final subjugation of Macassar in 1699.[17]

انظر أيضاً

- الإسلام في إنگلترة

- الپروتستانتية في تركيا

- الپروتستانتية في پاكستان

- الپروتستانتية في مصر

- المورمونية والإسلام

- الإسلام والأديان الأخرى

- تقسيم العالم في الإسلام

- Pallache family

- الپروتستانتية واليهودية

- العصبة الشمالكالدية

- On War Against the Turk

Notes

- ^ أ ب Goody 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Nițulescu, Daniel (6 May 2016). "The Influence of the Ottoman Threat on the Protestant Reformation (Reformers)". Andrews Research Conference. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Peace of Nuremberg". Oxford Reference (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Grieve, Paul (7 Feb 2013). A Brief Guide to Islam: History, Faith and Politics: The Complete Introduction. The Development of Islam: Shi'a and Catholics: Hachette UK. ISBN 9781472107558.

- ^ Allen, Jr., John L. (10 Nov 2009). The Future Church: How Ten Trends are Revolutionizing the Catholic Church (unabridged ed.). Crown Publishing Group. pp. 442–3. ISBN 9780385529532.

- ^ Smith, John MacDonald; Quenby, John, eds. (2009). Intelligent Faith: A Celebration of 150 Years of Darwinian Evolution (illustrated ed.). John Hunt Publishing. p. 245. ISBN 9781846942297.

- ^ Rogerson, J. W.; Lieu, Judith M. (16 Mar 2006). The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies (reprint ed.). OUP Oxford. p. 829. ISBN 9780199254255.

- ^ Hubbard-Brown, Janet (2007). Shirin Ebadi. Infobase Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 9781438104515.

- ^ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise A. (16 Mar 2015). Global Connections (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780521761062.

- ^ Schmidt 2001, p. 104.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Goffman 2002, p. 111.

- ^ Goffman 2002, p. 110.

- ^ Goffman 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Arand 2018, p. 167-169.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmiller2005 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةroupp1996 - ^ أ ب Boxer, C.R; WIC (1977). The Dutch Seaborne Empire, 1600-1800. London: Hutchinson. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-09-131051-6.

References

- Burton, Jonathan (2005). Traffic and Turning: Islam and English Drama, 1579-1624. Newark: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-0-87413-913-6.

- Goffman, Daniel (2002). The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. New approaches to European history. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45280-9.

- Goody, Jack (2004). Islam in Europe. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-3192-9.

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl (2007). The Jamestown Project. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02474-8.

- Parker, Geoffrey; Smith, Lesley M., eds. (1978). The General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-8865-9.

- Nicoll, Allardyce (2002). Shakespeare Survey With Index 1-10. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52347-9.

- Schmidt, Benjamin (2001). Innocence Abroad: The Dutch Imagination and the New World, 1570-1670. Cambrdige, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80408-0.

External links

- Wittenburg and Mecca issue of Logia: A Journal of Lutheran Theology