بوريس پاسترناك

بوريس پاسترناك | |

|---|---|

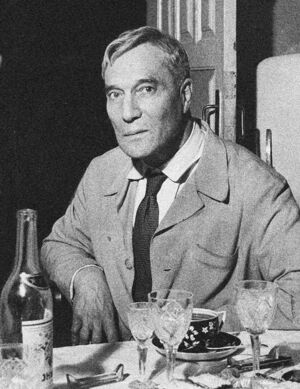

بوريس پاسترناك عام 1959 | |

| وُلِد | بوريس ليونيدوڤيتش پاسترناك 10 فبراير 1890 موسكو، الامبراطورية الروسية |

| توفي | 30 مايو 1960 (70 عاماً) پردلكينو، الاتحاد السوڤيتي |

| الوظيفة | شاعر، كاتب |

| الجنسية | الامبراطورية الروسية (1890–1917) روسيا السوڤيتية (1917–1922) الاتحاد السوڤيتي (1922–1960) |

| أبرز الأعمال | حياة شقيقتي، الولادة الثانية، دكتور ژيڤاگو |

| جوائز بارزة | جائزة نوبل في الأدب (1958) |

بوريس ليونيدوڤيتش پاسترناك (روسية: Бори́с Леони́дович Пастерна́к; النطق الروسي: [bɐˈrʲis lʲɪɐˈnʲidəvʲɪtɕ pəstɨrˈnak]؛[1] (إنگليزية: Boris Leonidovich Pasternak)؛ /ˈpæstərnæk/؛[2] و. 10 فبراير 1890 - ت. 30 مايو 1960)، هو شاعر، روائي، ومترجم أدبي روسي. ألف عام 1917 أولى دواوينه الشعرية، حياة شقيقتي، الذي نُشر في برلين عام 1922 وسرعان ما أهم الدواوين الشعرية باللغة الروسية. ترجم پاسترناك مسرحيات لگوته، شيلر، كالدرون لا باركا وشيكسپير ولا تزال تحظى بشعبية كبيرة لدى الجماهير الروسية.

أشهر أعمال پاسترياك، رواية دكتور ژيڤاگو (1957)، التي تدور حول الثورة الروسية 1905 والحرب العالمية الثانية. رُفض نشر الرواية في الاتحاد السوڤيتي، لكن مسودتها هُربت إلى ألمانيا للنشر.[3] حاز پاسترياك جائزة نوبل في الأدب عام 1958، الحدث الذي أثار غضب الحزب الشيوعي السوڤيتي، مما أجبره على رفض الجائزة، على الرغم من أن أحفاده تمكنوا من قبولها باسمه في عام 1989. أصبحت دكتور ژيڤاگو جزءاً المنهج المدرسي الروسي منذ 2003.[4]

السنوات المبكرة

وُلد پاسترياك في موسكو في 10 فبراير 189، لعائلة يهودية ثرية.[5] كان والده رسام ما بعد الانطباعية ليونيك پاسترياك، أستاذاً في مدرسة موسكو للرسم والنحت والعمارة. وكانت والدته روزا كوفمان، عازلة بيانو وابنة رجل صناعة من أدويسا، إيزادور كوفمان. كان لپاسترياك شقيقاً أصغر يدعى ألكس وشقيقتين؛ ليديا وجوزفين. ادعت العائلة أنها تنحدر من جهة الأب من إسحاق أباربانيل، فيلسوف ومعلق توراتي شهير من القرن الخامس عشر، وخازن الپرتغال.[6]

التعليم المبكر

في الفترة من 1904 حتى 1907، كان بوريس پاسترناك زميل لپيتر مينتشايڤيتش في (1890–1963) دير المبيت المقدس بوشايف لاڤرا في غرب أوكرانيا. واكن مينايڤيتش ينحدر من أسرة أوكرانيا أرثوذوكسية وكان پاسترناك من أسرة يهودية. كان پاسترناك يشعر بالإرتباك عند ارتياه الأكاديمية الحربية أثناء سنوات صباه. كن زي دير الطلاب العسكريين يشبه زي أكاديمية القيصر ألكسندر الثالث العسكرية، بينما كانت معظم المدارس تستخدم زيها العسكري المميز المصمم خصيصا لها كعادة المدارس في أوروبا الشرقية وروسيا. تفرق أصدقاء الصبى عام 1908، الذي كانوا أصدقاء ذوي أراء سياسية مهتلفة، وم يلتقوا مرة أخرى؛ فقد ذهب پاسترناك إلى معهد موسكو لدراسة الموسيقى _ثم ألمانيا لدراسة الفلسفة) بينما ذهب مينتشاكيڤيتش إلى إلى جامعة لڤيڤ لدراسة التاريخ والفلسفة. كان أبعاد شخصية سترلنيكوڤ الطيبة في رواية دكتور زيڤاجو مبنية على شخصية پيتر مينتشاكيڤيتش، فالعديد من شخصيات هي شخصيات مركبة. بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى والثورة والنضال ضد الحكومة المؤقتة أو الجمهورية في عهد كرنسكي والهرب من السجن الشيوعي والإعدام سافر مينتشاكيڤيتش عبر صربيا عام 1917 وحصل على الجنسية الأمريكية، بينما بقلا پاسترناك في روسيا.

في رسالة إلى جاكلين دى پرويارت، يقول پاسترناك:

في الصغر قامت مربيتي بتعميدي، ولكن بسبب القيود المفروضة على اليهود وخاصة على عائلة معفاة من تلك القيود لأنها تتمتع بسمع جيدة حسب رؤية أبي كفنان صاعدن كان هناك شئ معقد في الأمر، فكان دائمًا بمثابة سر وأمر حميمي إلى حد ما، مصدرا للإلهام النادر والاستثنائي بدلا من أن يؤخذ بهدوء على أنه أمر مسلّم به. واعتقد أن هذا كان مصدر تميزي، فقد شغلت المسيحية معظم أرجاء مخي في السنوات بين 1910-19012، حيث كانت الأساس أثناء تشكيل تميزي- والطريقة التي أراى بيها الامور، العالم والحياة...[7]

بعد فترة قصيرة من إنضمام والدي پاسترناك إلى الحركة التولستوية، حيث كان ليو تولستوي صديق مقرب للعائلة، يتذكر پاسترناك "كان والدي يرسم كتبه ويذهب لرؤيته، ويبجله... ويصبح البيت كله ينبض بروحه ."[8]

في أحد المقالات عام 1956، يتذكر پاسترناك انهماك والده في الإنتهاء من رسومات رواية تولستوي البعث.[9] ويقول پاسترناك أن الرواية نشرت على أعداد في مجلة نيڤا على يد الناشر فيودور ماركس، المقيم سان پطرسبرگ. استلهمت اللوحات من تأمب العديد من الأماكن كقاعات المحكمة والسجون والقطارات، وبروح الواقعية، ولضمان أن إنتهاء الرسوم في الموعد الذي تحدده المجلة، تم تعيين سائثي القطارات لجمع الرسوم شخصيًا.

ذهلت مخيلتي كطفل بمشهد سائق القطار بزي موظف السكةالحديدية يقف منتظرًا أمام باب المطبخ كأنه يقف على رصيف القطار عند المقصورة عند المغادرة، في الوقت نفسه الذي يغلي فيه غراء جونير على الموقد، وكان يتم تجفيف الرسوم بسرعو وتثبيتها ولصقها على ألواح من الورق المقوى وطيها وربطها. قم يتم هتم الطرود، عندما يتم الإنتهاء منها وتسليمها إلى سائق القطار.[9]

حسب ماكس هايوارد "في نوفمبر 1910، عندما فر تولستوي ومات في منزل ناظر المحطة في استابوڤو ذهب إلى هناك ليونيد پاسترناك فور علمه عبر التلگرام واخذ بوريس معخ ورسم لوحة لتولستوي على فراش الموت."[10] كان من أشهر الزوار المترددين على منزل پاسترناك سرجي رخمانينوف أليكساندر سكريابين لڤ شستوڤ وررايتر ماريا ريلك، وكان پاسترناك يطمح فبادئ الأمر أن يكون موسيقي.[11]

ألهم سكريابين پاسترناك، فدرس لفترة قصيرة في معهد موسكو للموسيقى. في 1910، وفجأة ذهب إلى ألمانيا إلى جامعة ماربوگ حيث درس على يد فلاسفة الكانطية الجديدة ومنهم هرمان كوهن ونيكولاي هارتمان وپول ناورپ.

حياته المهنية

أولگا فرايدنبرگ

في عام 1910، التقى پاسترناك مرة أخرى بابنة عمه أوگا فريدنبرگ (1890-1955). كانا يتشاركا نفس غرفة الأطفل لكنهم افترقا عندما انتقلت عائلة فريدنبرگ إلى سانت بطرسبرگ.

ووقعا في الحب على الفور لكنهم لم يكونوا حبيبين أبدًا وبرغم أن الروماسية كانت واضحة في الرسائل التي تبادلاها إلا أن پاسترناك كتب:

أنتِ لا تعرفين كيف نما شعوري المعذب ونما حتى أصبح الأمر واضحًا بالنسبة لي وللأخرين. بينما كنتِ تسيرين بجانبي منفصلة، لم أستطع التعبير عنها لكم، كانا نوع غريب من لقرب، كأننا أنا وانت ممغرمين بشئ غريب عن كلينا، بشئ بعيد عن كلينا بسبب عجزه غير الطبيعي عن الاعتياد على الجانب الأخر من الحياة.

تطور حب أبناء العمومة إلى صداقة طويلة الأمد. فبداية من 1910 بدء الأثين في تبادل الخطابات واستمرا ذلكل مجة40 عام حتى عام 1954 وكانا قد ألتقيا للمرة الأخيرة عام 1936.[12][13]

إيدا ويسوتسكي

وقع پاسترناك في غرام إيدا ويسوتزكايا، وهي فتاة مش عائلة يهودية بارزة تعيش في موسكو وويعملون في تجارة الشاي ويسوتسكي تي وهي أحد أكبر شركات الشاي في العالم. كان پاسترناك يدرس لها في السنة الأخيرة من المدرسة وساعدها للتحضير من أجل الأختبارات والتقيا في ماربورگ خلال صيف 1912 عندما ذهب والده ليونيد پاسترناك لرسم بورتريه لها.[14] وبرغم أن الأستاذ كوهن شجعه على البقاء في ألمانيا للحصول على درجة الدكتوراه في الفلسفة إلا أن پاسترناك لم يوافق، وعاد إلى موسكو في الوقت نفسه التي اندلعت فيه الحرب العالمية الأولى، وفي أعقاب تلك الأحداث تقدم للزواج من إيدا، رغم ذلك وانزعجت عائلة ويسوتسكي من ضعف إمكانات پاسترناك فرفضته إيدا وكتب قصيدة "ماربورگ" (1917) التي تحدث فيها عن حبه لها ورفضها :[14]

ارتجفت، وتأججت، فاشعلت،

ارتعشت. وتقدمت إليها-لكن متأخرًا

متأخرًا للغاية، كنت خائف،

أشفق على عبراتها، فأنا مبارك أكثر من أي قديس.

في هذا الوقت، عندما عاد إلى روسيا، كان قد أنضم إلى جماعة الطرد المستقبلية الروسية، والي تعرف ب تسنتريفوگا،[15] وبصفته عازف؛ كانت الشعر بالنسبة له مجرد هواية،[16] نشر في مجلة الجماعة التي حملت اسم ليريكا أوائل قصائده، وكان في أوج انخراطه مع الجماعة في عام 1914 عندما نشر مقال ساخر في مجلة روكونوگ وهاجم فيه قائد "مجلة الشعر" الحاقد ڤاديم شرشنڤيتش والذي كان ينتقد مجلة ليريكا والمستقبليين الإگوريين لأن شرشنڤيتش نفسه منع من التعاون كع الجماعة لأنه لم يكن ذي موهبة [15] تسبب ذلك في معركة كلامية بين أعضاء الجماعة، والنضال من أجل الاعتراف بكونهم أول وأصدق مستقبليين روس؛ ودخل في تلك المعركة التكعيبيين المستقبليين، والذي كانوا بالفعل سيئي السمعة بسبب سلوكهم الفاضح. بعد تلك الأحداث بفترة قصيرة تم نشر كتابي پاسترناك الشعرييين الأولى والثانية .[17]

ألهمت قصة حب فاشلة أخرى 1917 ألهمته لكتابة الأشعار الموجودة في كتابة ديوانه الثالث وأول كتاب كبير يقوم بكتابته وهو أختي، حياتي، نجح پاسترناك بمهارة في قصائده الأةلى في إخفاء إهتمامه بفلسفة إمانوِل كانط، وتضم بنية القصائد جناس لافت للنظر، تراكيب إيقاعية غير اعتيادية وألفاظ يومية، وإشارات خفية لشعرائه المفضلين من امقال ريلكه ولرمونتوڤ وپوشكين، وشعراء ألمان رومانسيين. خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى، قام پاسترناك بالتدريس والعمل في مصنع كيميائي في ڤسڤولودڤوڤيلڤ بالقرب من پرم، مما ألهمه لكتابة دكتور ژيڤاگو بعد عدة سنوات. وعلى عكس باقي أفراد عائلته والعديد من أصدقائه المقربين لم يختر پاسترناك ترك روسيا بعد ثورة أكتوبر عام 1917، وحسب ما قاله ماكس هايوارد،

ظل پاسترناك في موسكو خلال الحرب الأهلية الروسية (1918–1920) محاولًا ألا يهرب إلى الخارج أو الجنوب الأبيض المحتل كما فعل العديد من الكتاب الروس

في ذلك الوقت، فلا شك أنه أنبهر بشكل لحظي،مثل يوري ژيڤاگو، ب"الجراحة الرائع" المتمثلة في إستيلاء البلاشفة على السلطة في أكتوبر 1917، ولكن-مرة أخى وحسب الأدلة الموجودة فالرواية، وبرغم إعجابه الشخصي ب ڤلاديمير لنين، الذي رأه في الكونگرس السوڤيتي التاسع عام 1921- بدأت ترواده شكوك حول إدعاءات النظام ووثائق تفويض، إلى جانب نظام الحكم،فقد جعل نقص الغذاء والوقود وعمليات نهب الإرهاب الأأحمر، الحياة غير مستقرة في تلك السنوات خاصة بالنسبة إلى النخبة المثقفة "البرجوازية". في رسالة إلى پاسترناك من الخارج في العشرينات ، ذكرته مارينا تسڤيتايڤا كيف أنها قد ألتق به في الشارع عام 1919 عندما كان في طريقه لبيع بعض الكتب القيمة من مكتبه من أجل شراء الخبز.

وواصل كتابة الأعمال الأصلية وترجمتها، ولكن بعد 1918 أصبح من المستحيل أن ينشر الأعمال، والطريقة الوحيدة لتعرف على أعمال المرء هي الإعلان عنه في عدة مقاهي "أدبية"، وحينها تبدأ ساميزدات- من خلاله يتم تداول المخطوط، وعن طريق ذلك الأسلوب اصبح كتاب أختي، الحياة متاح لعدد لجمهور أعرض.[18]

عندم نشر ديوان أختي، الحياة أخيرًا عام 1922، كان بمثابة ثورة في الشعر الروسي، وأصبح پاسترناك قدوة للشعراء الشباب، واحدث تغييرًا جذريًا في شعر أوسيب ماندلشتام ومارينا تسڤتايڤا وغيرهم. بعد أختي، الحياة، ألف پاسترناك العديد من القصائد المحكمة والمتفاوتة في الجودة ومن ضمنها رائعته حلقة الإنسكار الشعرية (1921)، واثنى كل من الكتاب الداعمين للإتحاد السوڤيتي والكتاب المهاجرين البيض على شعر پاسترناك واعتبروه إلهام نقي وجامح. في نهاية العشرينات، شارك أيضًا في مراسلات ثلاثية مع ريلكه ومارينا تسڤتايڤا.[19] برغم إنقضاء العشرينات، إزداد شعور پاسترناك أن أسلوبه المبهج يتعارض مع شريحة القراء الذين لم يحصلوا على قدر كافي من التعليم، فحاول أن يجعل شعره أوضح من خلال إعادة تأليف أعماله المبكرة وبدء قصيدتين مطولتين عن الثورة الروسية 1905. أتجه أيضًا إلى النثر وكتابة عدد من قصص السيرة الذاتية، والتي كان من أبرزها "طفولة لوڤرز" و"المرور الآمن" (مجموعة طفولة ژنيا وقصص أخرى والتي نشرت عام 1982.) [20]

في عام 1922 ترزج پاسترناك من إڤاگنيا لوري، التي كانت طالبة في معهد الفنون، وفي العام التالي رُزق بابنهم إڤاگني. تشير قصيدة پاسترناك "إحياء ذكرى رايسنر" إلى دعمه لأعضاء قيادات الحزب الشيوعي الذين ظلوا ثوريين حتى عام 1926 [21] ويعتقد أنها كتب بعد وفاة قائدة البلاشفة الأسطورية لاريسا ريسنير الصادمة بالحمشى النمشية في سن ال30 في فبراير من ذلك العام.

في عام 1927، دعا أقرب أصدقاء پاسترناك ڤلاديمير ماياكوڤسكي ونيكولاي أسيڤ إلى الخضوع الكامل للفنون لاحتياجات الحزب الشيوعي السوڤيتي.[22] في رسالة إلى أخته جوزفين كتب پاسترناك عن عزمه "لقطع علاقته" مع كليهما. وبرغم ذلك عبر عن مرارة الأمر، لكنه قال مفسرًا أنه أمر لا مفر منه:

They don't in any way measure up to their exalted calling. In fact, they've fallen short of it but – difficult as it is for me to understand – a modern sophist might say that these last years have actually demanded a reduction in conscience and feeling in the name of greater intelligibility. Yet now the very spirit of the times demands great, courageous purity. And these men are ruled by trivial routine. Subjectively, they're sincere and conscientious. But I find it increasingly difficult to take into account the personal aspect of their convictions. I'm not out on my own – people treat me well. But all that only holds good up to a point. It seems to me that I've reached that point

أنهما لا يرتقيان أبدًا إلى دعوتهم المحيدة، فالحقيقة في الواقع، هما أدنى من ذلك ولكن من الصعب علي أن أفهم- قد يقول السفسطائي الحديث أن السنوات الأخيرة تطلبت في الحقيقة تقليص الضمير والشعور تحت مسمى المزيد من الذكاء. ومع ذلك فإن روح العصر ذاتها تتطلب الآن نقاوة كبيرة وشجاعة. وهؤلاء الرجال يحكمهم روتين تافه.

.[23]

By 1932, Pasternak had strikingly reshaped his style to make it more understandable to the general public and printed the new collection of poems, aptly titled The Second Birth. Although its Caucasian pieces were as brilliant as the earlier efforts, the book alienated the core of Pasternak's refined audience abroad, which was largely composed of anti-communist emigres.

In 1932 Pasternak fell in love with Zinaida Neuhaus, the wife of the Russian pianist Heinrich Neuhaus. They both got divorces and married two years later.

He continued to change his poetry, simplifying his style and language through the years, as expressed in his next book, Early Trains (1943).

قصائد ستالين الساخرة

In April 1934 Osip Mandelstam recited his "Stalin Epigram" to Pasternak. After listening, Pasternak told Mandelstam: "I didn't hear this, you didn't recite it to me, because, you know, very strange and terrible things are happening now: they've begun to pick people up. I'm afraid the walls have ears and perhaps even these benches on the boulevard here may be able to listen and tell tales. So let's make out that I heard nothing."[24]

On the night of 14 May 1934, Mandelstam was arrested at his home based on a warrant signed by NKVD boss Genrikh Yagoda. Devastated, Pasternak went immediately to the offices of Izvestia and begged Nikolai Bukharin to intercede on Mandelstam's behalf.

Soon after his meeting with Bukharin, the telephone rang in Pasternak's Moscow apartment. A voice from The Kremlin said, "Comrade Stalin wishes to speak with you."[24] According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak was struck dumb. "He was totally unprepared for such a conversation. But then he heard his voice, the voice of Stalin, coming over the line. The Leader addressed him in a rather bluff uncouth fashion, using the familiar thou form: 'Tell me, what are they saying in your literary circles about the arrest of Mandelstam?'" Flustered, Pasternak denied that there was any discussion or that there were any literary circles left in Soviet Russia. Stalin went on to ask him for his own opinion of Mandelstam. In an "eager fumbling manner" Pasternak explained that he and Mandelstam each had a completely different philosophy about poetry. Stalin finally said, in a mocking tone of voice: "I see, you just aren't able to stick up for a comrade," and put down the receiver.[24]

التطهير الكبير

According to Pasternak, during the 1937 show trial of General Iona Yakir and Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the Union of Soviet Writers requested all members to add their names to a statement supporting the death penalty for the defendants. Pasternak refused to sign, even after leadership of the Union visited and threatened him.[25] Soon after, Pasternak appealed directly to Stalin, describing his family's strong Tolstoyan convictions and putting his own life at Stalin's disposal; he said that he could not stand as a self-appointed judge of life and death. Pasternak was certain that he would be arrested,[25] but instead Stalin is said to have crossed Pasternak's name off an execution list, reportedly declaring, "Do not touch this cloud dweller" (or, in another version, "Leave that holy fool alone!")[26]

Pasternak's close friend Titsian Tabidze did fall victim to the Great Purge. In an autobiographical essay published in the 1950s, Pasternak described the execution of Tabidze and the suicides of Marina Tsvetaeva and Paolo Iashvili as the greatest heartbreaks of his life.

Ivinskaya wrote, "I believe that between Stalin and Pasternak there was an incredible, silent duel."[27]

الحرب العالمية الثانية

When the Luftwaffe began bombing Moscow, Pasternak immediately began to serve as a fire warden on the roof of the writer's building on Lavrushinski Street. According to Ivinskaya, he repeatedly helped to dispose of German bombs which fell on it.[28]

In 1943, Pasternak was finally granted permission to visit the soldiers at the front. He bore it well, considering the hardships of the journey (he had a weak leg from an old injury), and he wanted to go to the most dangerous places. He read his poetry and talked extensively with the active and injured troops.[28]

With the end of the war in 1945, the Soviet people expected to see the end of the devastation of Nazism, and hoped for the end of Stalin's Purges. But sealed trains began carrying large numbers of prisoners to the Soviet Gulags. Some were Nazi collaborators who had fought under General Andrey Vlasov, but most were ordinary Soviet officers and men. Pasternak watched as ex-POWs were directly transferred from Nazi Germany to Soviet concentration camps. White emigres who had returned due to pledges of amnesty were also sent directly to the Gulag, as were Jews from the Anti-Fascist Committee and other organizations. Many thousands of innocent people were incarcerated in connection with the Leningrad Affair and the so-called Doctor's Plot, while whole ethnic groups were deported to Siberia.[29]

Pasternak later said, "If, in a bad dream, we had seen all the horrors in store for us after the war, we should not have been sorry to see Stalin fall, together with Hitler. Then, an end to the war in favour of our allies, civilized countries with democratic traditions, would have meant a hundred times less suffering for our people than that which Stalin again inflicted on it after his victory."[30]

أولگا إيڤينسكايا

In October 1946, the twice married Pasternak met Olga Ivinskaya, a 34 year old single mother employed by Novy Mir. Deeply moved by her resemblance to his first love Ida Vysotskaya,[31] Pasternak gave Ivinskaya several volumes of his poetry and literary translations. Although Pasternak never left his wife Zinaida, he started an extramarital relationship with Ivinskaya that would last for the remainder of Pasternak's life. Ivinskaya later recalled, "He phoned almost every day and, instinctively fearing to meet or talk with him, yet dying of happiness, I would stammer out that I was "busy today." But almost every afternoon, toward the end of working hours, he came in person to the office and often walked with me through the streets, boulevards, and squares all the way home to Potapov Street. 'Shall I make you a present of this square?' he would ask."

She gave him the phone number of her neighbour Olga Volkova who resided below. In the evenings, Pasternak would phone and Volkova would signal by Olga banging on the water pipe which connected their apartments.[32]

When they first met, Pasternak was translating the verse of the Hungarian national poet, Sándor Petőfi. Pasternak gave his lover a book of Petőfi with the inscription, "Petőfi served as a code in May and June 1947, and my close translations of his lyrics are an expression, adapted to the requirements of the text, of my feelings and thoughts for you and about you. In memory of it all, B.P., 13 May 1948."

Pasternak later noted on a photograph of himself, "Petőfi is magnificent with his descriptive lyrics and picture of nature, but you are better still. I worked on him a good deal in 1947 and 1948, when I first came to know you. Thank you for your help. I was translating both of you."[33] Ivinskaya would later describe the Petőfi translations as, "a first declaration of love."[34]

According to Ivinskaya, Zinaida Pasternak was infuriated by her husband's infidelity. Once, when his younger son Leonid fell seriously ill, Zinaida extracted a promise from her husband, as they stood by the boy's sickbed, that he would end his affair with Ivinskaya. Pasternak asked Luisa Popova, a mutual friend, to tell Ivinskaya about his promise. Popova told him that he must do it himself. Soon after, Ivinskaya happened to be ill at Popova's apartment, when suddenly Zinaida Pasternak arrived and confronted her.

Ivinskaya later recalled,

But I became so ill through loss of blood that she and Luisa had to get me to the hospital, and I no longer remember exactly what passed between me and this heavily built, strong-minded woman, who kept repeating how she didn't give a damn for our love and that, although she no longer loved [Boris Leonidovich] herself, she would not allow her family to be broken up. After my return from the hospital, Boris came to visit me, as though nothing had happened, and touchingly made his peace with my mother, telling her how much he loved me. By now she was pretty well used to these funny ways of his.[18]

In 1948, Pasternak advised Ivinskaya to resign her job at Novy Mir, which was becoming extremely difficult due to their relationship. In the aftermath, Pasternak began to instruct her in translating poetry. In time, they began to refer to her apartment on Potapov Street as, "Our Shop."

On the evening of 6 October 1949, Ivinskaya was arrested at her apartment by the KGB. Ivinskaya relates in her memoirs that, when the agents burst into her apartment, she was at her typewriter working on translations of the Korean poet Won Tu-Son. Her apartment was ransacked and all items connected with Pasternak were piled up in her presence. Ivinskaya was taken to the Lubyanka Prison and repeatedly interrogated, where she refused to say anything incriminating about Pasternak. At the time, she was pregnant with Pasternak's child and had a miscarriage early in her ten-year sentence in the GULAG.

Upon learning of his mistress' arrest, Pasternak telephoned Liuisa Popova and asked her to come at once to Gogol Boulevard. She found him sitting on a bench near the Palace of Soviets Metro Station. Weeping, Pasternak told her, "Everything is finished now. They've taken her away from me and I'll never see her again. It's like death, even worse."[35]

According to Ivinskaya, "After this, in conversation with people he scarcely knew, he always referred to Stalin as a 'murderer.' Talking with people in the offices of literary periodicals, he often asked: 'When will there be an end to this freedom for lackeys who happily walk over corpses to further their own interests?' He spent a good deal of time with Akhmatova—who in those years was given a very wide berth by most of the people who knew her. He worked intensively on the second part of Doctor Zhivago."[35]

In a 1958 letter to a friend in West Germany, Pasternak wrote, "She was put in jail on my account, as the person considered by the secret police to be closest to me, and they hoped that by means of a gruelling interrogation and threats they could extract enough evidence from her to put me on trial. I owe my life, and the fact that they did not touch me in those years, to her heroism and endurance."[36]

ترجمة گوته

Pasternak's translation of the first part of Faust led him to be attacked in the August 1950 edition of Novy Mir. The critic accused Pasternak of distorting Goethe's "progressive" meanings to support "the reactionary theory of 'pure art'", as well as introducing aesthetic and individualist values. In a subsequent letter to the daughter of Marina Tsvetaeva, Pasternak explained that the attack was motivated by the fact that the supernatural elements of the play, which Novy Mir considered, "irrational," had been translated as Goethe had written them. Pasternak further declared that, despite the attacks on his translation, his contract for the second part had not been revoked.[37]

دكتور ژيڤاگو

مقالة مفصلة: دكتور ژيڤاگو (رواية)

مقالة مفصلة: دكتور ژيڤاگو (رواية)

قبيل عدة سنوات من الحرب العالمية الثانية، استقر پاسترناك وزوجته في قرية صغيرة ضمت مجموعة من الكتاب والمثقفين. حب پاسترناك للحياة منح شعره نفسا متفائلا وعكس ذلك في تجسيده للشخصية الاساسية في رواية الدكتور ژيڤاگو، أما بطلة الرواية لارا فقد قيل أنها تمثل عشيقته اولگا إيڤنسكايا. بسبب من الانتقاد الشديد الموجه للنظام الشيوعي، لم يجد باسترناك ناشراً يرضى بنشر الرواية في الاتحاد السوڤيتي، لذلك فقد هربت عبر الحدود إلى إيطاليا، ونشرت في عام 1957، مسببة أصداءً واسعة: سلبا في الاتحاد السوڤيتي، وإيجابيا في الغرب. رغم أن أحداً من النقاد السوفيت لم يكن قد اطلع على الرواية إلا أنهم هاجموها بعنف، بل وطالبوا بطرد پاسترناك.

في العام التالي 1958 منح پاسترناك جائزة نوبل في الأدب، لكن باسترناك رفضها. توفي بوريس في 30 مايو 1960 ولم يحضر جنازته سوى بعض المعجبين المخلصين. لم تنشر الدكتور ژيڤاگو في الاتحاد السوڤيتي إلا في عام 1987 مع بداية الپروسترويكا والگلاسنوست.

حولت رواية الدكتور ژيڤاگو إلى فلم سينمائي ملحمي عام 1965، من إخراج روبرت بولت، بطولة عمر الشريف وجولي كريستي، وقام موريس گار بتأليف موسيقاه التصويرية. حصد الفيلم خمسة جوائز أوسكار، ويعد ثامن أنجح فيلم على مستوى شباك التذاكر العالمي، متجاوزا فيلم تايتانيك عندما تحذف معدلات التضخم وتعدل بشكل نسبي.

جائزة نوبل

According to Yevgeni Borisovich Pasternak, "Rumors that Pasternak was to receive the Nobel Prize started right after the end of World War II. According to the former Nobel Committee head Lars Gyllensten, his nomination was discussed every year from 1946 to 1950, then again in 1957 (it was finally awarded in 1958). Pasternak guessed at this from the growing waves of criticism in USSR. Sometimes he had to justify his European fame: 'According to the Union of Soviet Writers, some literature circles of the West see unusual importance in my work, not matching its modesty and low productivity…'"[38]

Meanwhile, Pasternak wrote to Renate Schweitzer[39] and his sister, Lydia Pasternak Slater.[40] In both letters, the author expressed hope that he would be passed over by the Nobel Committee in favour of Alberto Moravia. Pasternak wrote that he was wracked with torments and anxieties at the thought of placing his loved ones in danger.

On 23 October 1958, Boris Pasternak was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize. The citation credited Pasternak's contribution to Russian lyric poetry and for his role in "continuing the great Russian epic tradition." On 25 October, Pasternak sent a telegram to the Swedish Academy: "Infinitely grateful, touched, proud, surprised, overwhelmed."[41] That same day, the Literary Institute in Moscow demanded that all its students sign a petition denouncing Pasternak and his novel. They were further ordered to join a "spontaneous" demonstration demanding Pasternak's exile from the Soviet Union.[42] On 26 October, the Literary Gazette ran an article by David Zaslavski entitled, Reactionary Propaganda Uproar over a Literary Weed.[43]

Furthermore, Pasternak was informed that, if he traveled to Stockholm to collect his Nobel Medal, he would be refused re-entry to the Soviet Union. As a result, Pasternak sent a second telegram to the Nobel Committee: "In view of the meaning given the award by the society in which I live, I must renounce this undeserved distinction which has been conferred on me. Please do not take my voluntary renunciation amiss."[44] The Swedish Academy announced: "This refusal, of course, in no way alters the validity of the award. There remains only for the Academy, however, to announce with regret that the presentation of the Prize cannot take place."[45]

According to Yevgenii Pasternak, "I couldn't recognize my father when I saw him that evening. Pale, lifeless face, tired painful eyes, and only speaking about the same thing: 'Now it all doesn’t matter, I declined the Prize.'"[38]

خطط الترحيل

Despite his decision to decline the award, the Soviet Union of Writers continued to demonise Pasternak in the State-owned press. Furthermore, he was threatened at the very least with formal exile to the West. In response, Pasternak wrote directly to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev,

I am addressing you personally, the C.C. of the C.P.S.S., and the Soviet Government. From Comrade Semichastny's speech I learn that the government, 'would not put any obstacles in the way of my departure from the U.S.S.R.' For me this is impossible. I am tied to Russia by birth, by my life and work. I cannot conceive of my destiny separate from Russia, or outside it. Whatever my mistakes or failings, I could not imagine that I should find myself at the center of such a political campaign as has been worked up round my name in the West. Once I was aware of this, I informed the Swedish Academy of my voluntary renunciation of the Nobel Prize. Departure beyond the borders of my country would for me be tantamount to death and I therefore request you not to take this extreme measure with me. With my hand on my heart, I can say that I have done something for Soviet literature, and may still be of use to it.[46]

In The Oak and the Calf, Alexander Solzhenitsyn sharply criticized Pasternak, both for declining the Nobel Prize and for sending such a letter to Khrushchev. In her own memoirs, Olga Ivinskaya blames herself for pressuring her lover into making both decisions.

According to Yevgenii Pasternak, "She accused herself bitterly for persuading Pasternak to decline the Prize. After all that had happened, open shadowing, friends turning away, Pasternak's suicidal condition at the time, one can... understand her: the memory of Stalin's camps was too fresh, [and] she tried to protect him."[38]

On 31 October 1958, the Union of Soviet Writers held a trial behind closed doors. According to the meeting minutes, Pasternak was denounced as an internal White emigre and a Fascist fifth columnist. Afterwards, the attendees announced that Pasternak had been expelled from the Union. They further signed a petition to the Politburo, demanding that Pasternak be stripped of his Soviet citizenship and exiled to, "his Capitalist paradise."[47] According to Yevgenii Pasternak, however, author Konstantin Paustovsky refused to attend the meeting. Yevgeny Yevtushenko did attend, but walked out in disgust.[38]

According to Yevgenii Pasternak, his father would have been exiled had it not been for Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who telephoned Khrushchev and threatened to organize a Committee for Pasternak's protection.[38]

It is possible that the 1958 Nobel Prize prevented Pasternak's imprisonment due to the Soviet State's fear of international protests. Yevgenii Pasternak believes, however, that the resulting persecution fatally weakened his father's health.[48]

Meanwhile, Bill Mauldin produced a cartoon about Pasternak that won the 1959 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. The cartoon depicts Pasternak as a GULAG inmate splitting trees in the snow, saying to another inmate: "I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?"[49]

السنوات اللاحقة

Pasternak's post-Zhivago poetry probes the universal questions of love, immortality, and reconciliation with God.[50][51] Boris Pasternak wrote his last complete book, When the Weather Clears, in 1959.

According to Ivinskaya, Pasternak continued to stick to his daily writing schedule even during the controversy over Doctor Zhivago. He also continued translating the writings of Juliusz Słowacki and Pedro Calderón de la Barca. In his work on Calderon, Pasternak received the discreet support of Nikolai Mikhailovich Liubimov, a senior figure in the Party's literary apparatus. Ivinskaya describes Liubimov as, "a shrewd and enlightened person who understood very well that all the mudslinging and commotion over the novel would be forgotten, but that there would always be a Pasternak."[52] In a letter to his sisters in Oxford, England, Pasternak claimed to have finished translating one of Calderon's plays in less than a week.[53]

During the summer of 1959, Pasternak began writing The Blind Beauty, a trilogy of stage plays set before and after Alexander II's abolition of serfdom in Russia. In an interview with Olga Carlisle from The Paris Review, Pasternak enthusiastically described the play's plot and characters. He informed Olga Carlisle that, at the end of The Blind Beauty, he wished to depict "the birth of an enlightened and affluent middle class, open to occidental influences, progressive, intelligent, artistic".[54] However, Pasternak fell ill with terminal lung cancer before he could complete the first play of the trilogy.

وفاته

Boris Pasternak died of lung cancer in his dacha in Peredelkino on the evening of 30 May 1960. He first summoned his sons, and in their presence said, "Who will suffer most because of my death? Who will suffer most? Only Oliusha will, and I haven't had time to do anything for her. The worst thing is that she will suffer."[55] Pasternak's last words were, "I can't hear very well. And there's a mist in front of my eyes. But it will go away, won't it? Don't forget to open the window tomorrow."[55]

Shortly before his death, a priest of the Russian Orthodox Church had given Pasternak the last rites. Later, in the strictest secrecy, a Russian Orthodox funeral liturgy, or Panikhida, was offered in the family's dacha.[56]

ذكراه

After Pasternak's death, Ivinskaya was arrested for the second time, with her daughter, Irina Emelyanova. Both were accused of being Pasternak's link with Western publishers and of dealing in hard currency for Doctor Zhivago. All of Pasternak's letters to Ivinskaya, as well as many other manuscripts and documents, were seized by the KGB. The KGB quietly released them, Irina after one year, in 1962, and Olga in 1964.[57] By this time, Ivinskaya had served four years of an eight-year sentence, in retaliation for her role in Doctor Zhivago's publication.[58] In 1978, her memoirs were smuggled abroad and published in Paris. An English translation by Max Hayward was published the same year under the title A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak.

Ivinskaya was rehabilitated only in 1988. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Ivinskaya sued for the return of the letters and documents seized by the KGB in 1961. The Russian Supreme Court ultimately ruled against her, stating that "there was no proof of ownership" and that the "papers should remain in the state archive".[57] Ivinskaya died of cancer on 8 September 1995.[58] A reporter on NTV compared her role to that of other famous muses for Russian poets: "As Pushkin would not be complete without Anna Kern, and Yesenin would be nothing without Isadora, so Pasternak would not be Pasternak without Olga Ivinskaya, who was his inspiration for Doctor Zhivago.".[58]

Meanwhile, Boris Pasternak continued to be pilloried by the Soviet State until Mikhail Gorbachev proclaimed Perestroika during the 1980s.

In 1980, an asteroid 3508 Pasternak was named after Boris Pasternak.[59]

In 1988, after decades of circulating in Samizdat, Doctor Zhivago was serialized in the literary journal Novy Mir.[60]

In December 1989, Yevgenii Borisovich Pasternak was permitted to travel to Stockholm in order to collect his father's Nobel Medal.[61] At the ceremony, acclaimed cellist and Soviet dissident Mstislav Rostropovich performed a Bach serenade in honor of his deceased countryman.

A 2009 book by Ivan Tolstoi reasserts claims that British and American intelligence officers were involved in ensuring Pasternak's Nobel victory; another Russian researcher, however, disagreed.[62][63] When Yevgeny Borisovich Pasternak was questioned about this, he responded that his father was completely unaware of the actions of Western intelligence services. Yevgeny further declared that the Nobel Prize caused his father nothing but severe grief and harassment at the hands of the Soviet State.[64][48]

The Pasternak family papers are stored at the Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University. They contain correspondence, drafts of Doctor Zhivago and other writings, photographs, and other material, of Boris Pasternak and other family members.

Since 2003, the novel Doctor Zhivago has entered the Russian school curriculum, where it is read in the 11th grade of secondary school.[4]

التأثير الثقافي

- A minor planet (3508 Pasternak) discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina in 1980 is named after him.[65]

- Russian-American singer and songwriter Regina Spektor recites a verse from "Black Spring", a 1912 poem by Pasternak in her song "Apres Moi" from her album Begin to Hope.

- Russian-Dutch composer Fred Momotenko (Alfred Momotenko) wrote a companion composition to Sergej Rachmaninov's All-Night Vigil Op 37. based on the eponymous poem from the diptych Doktor Zhivago Na Strastnoy

اقتباسات

The first screen adaptation of Doctor Zhivago, adapted by Robert Bolt and directed by David Lean, appeared in 1965. The film, which toured in the roadshow tradition, starred Omar Sharif, Geraldine Chaplin, and Julie Christie. Concentrating on the love triangle aspects of the novel, the film became a worldwide blockbuster, but was unavailable in Russia until Perestroika.

In 2002, the novel was adapted as a television miniseries. Directed by Giacomo Campiotti, the serial starred Hans Matheson, Alexandra Maria Lara, Keira Knightley, and Sam Neill.

The Russian TV version of 2006, directed by Aleksandr Proshkin and starring Oleg Menshikov as Zhivago, is considered more faithful to Pasternak's novel than David Lean's 1965 film.

أعماله

أعمال مختارة

دواوين

- Twin in the Clouds (1914)

- Over the Barriers (1916)

- Themes and Variations (1917)

- My Sister, Life (1922)

- On Early Trains (1944)

- Selected Poems (1946)

- Poems (1954)

- When the Weather Clears (1959)

- In The Interlude: Poems 1945–1960 (1962)

روايات

- Safe Conduct (1931)

- Second Birth (1932)

- The Last Summer (1934)

- Childhood (1941)

- Selected Writings (1949)

- Collected Works (1945)

- Goethe's Faust (1952)

- Essay in Autobiography (1956)

- Doctor Zhivago (1957)

حياة شقيقتي

خلال صيف 1917 وبينما كان بوريس في سهل ساراتوڤ، عاش قصة حب عاصفة مع فتاة يهودية، تجربته تلك أوحت له بمجموعة شعرية كتبها خلال ثلاثة أشهر وامتنع عن نشرها – احراجا- لمدة أربع سنوات. عندما نشرت اخيرا في عام 1921 احدثت اثرا ثوريا عميقا على الشعر الروسي، وصار بوريس يعد مثالا يحتذى و يقلد بالنسبة لصغار الشعراء. بل ان ديوانه هذا أثر وغير من أسلوب شعراء كبار في الساحة آنذاك.

نقاد مختلفون مثل ڤلاديمير ماياكوڤسكي، أندريه بيلي، وڤلاديمير ناپوكوڤ، اطروا عمل باسترناك بإعتباره إبداعاً أصيلاً وغير مكبوح الجماح.

في أواخر العشرينات شارك باسترناك في مراسلات ثلاثية مع ريلكه وتسفتاييفا. في تلك الفترة بدأ باسترناك يشعر ان اسلوبه الشاعري لا يناسب المناخ الادبي للواقعية الاجتماعية التي كان الحزب الشيوعي السوفيتي يدعمها و يروج لها.حاول باسترناك للتوافق مع ذلك ان يقدم شعره بطريقة تكون اكثر مقروءة من الجماهير ومن القارئ العادي. حتى انه اعاد صياغة قسم من قصائده القديمة للتوافق مع المفاهيم الجديدة.و كتب كذلك قصيدتين طويلتين في الثورة الروسية. في هذه المرحلة، بدأ توجهه نحو النثر وقدم " طفولة العشاق" و" الوصول الامن".

الولادة الثانية

في عام 1932 پاسترناك غير من أسلوبه بشكل جذري ليتوافق مع المفاهيم السوفيتية الجديدة. فقد سمى مجموعته الجديدة "الولادة الثانية" 1932، التي رغم أن جزءها القوقازي كان مبتكراً من الناحية الادبية، إلا أن محبي باسترناك في الخارج أصيبوا بخيبة أمل. ذهب باسترناك إلى أبعد من هذا في التبسيط والمباشرة في الوطنية في مجموعته التالية "قطارات مبكرة" 1943، الامر الذي دفع نابوكوڤ إلى وصفه بال"بولشفي المتباكي"، و" إميلي ديكنسون في ثياب رجل".

خلال ذروة حملات التطهير في لأواخر الثلاثينات، شعر باسترناك بالخذلان والخيبة من الشعارات الشيوعية وامتنع عن نشر شعره وتوجه إلى ترجمة الشعر العالمي إلى الروسية: ترجم لشكسبير (هاملت، ماكبث، الملك لير) وگوته ( فاوست) وريلكه، بالإضافة إلى مجموعة من الشعراء الجورجيين الذين كان يحبهم ستالين.

ترجمات باسترناك لشكسبير صارت رائجة جدا رغم أنه اتهم دوما لأنه كان يحول شكسبير إلى نسخة من باسترناك. عبقرية باسترناك اللغوية انقذته من الاعتقال اثناء حملات التطهير ، حيث مررت قائمة اسماء الذين صدرت اوامر بأعتقالهم امام ستالين ، فحذفه قائلا : لا تلمسوا ساكن الغيوم هذا.

أهمَّ ما كتبه باسترناك نثراً كان روايته «الدكتور جيڤاگو» Doctor Zhivago التي صدرت في إيطالية عام 1957 مترجمة إلى الإيطالية أولاً، ثم تلتها طبعات بالروسية؛ وتحكي قصة حياة طبيب ولد أواخر القرن التاسع عشر وأنهى دراسة الطب أثناء الحرب العالمية الأولى، مما أتاح للمؤلف أن يعطي صوراً عن الحياة في روسية قبل الحرب وأثناءها، ثم أيام اشتعال الثورة في أثناء الحرب الأهلية وبعدها. كتب باسترناك هذه الرواية وهو ما يزال واقعاً تحت تأثير فرحِهِ بانتهاء الحرب العالمية الثانية وانتصار شعبه فيها وأمله بتجديدٍ طالما انتظر المجتمع السوڤيتي أن يَحمِل إليه الحرية والديمقراطية وينهي «المرحلة الجدانوفية» في التعامل مع الأدب والأدباء، وأن يضع حداً لأعمال القمع والمضايقات والاتهامات والمحاكمات والحظر التي يتعرض لها المثقفون وغيرهم. لكن سرعان ما تبدى أن هذا الأمل المفعم بالفرح ليس إلاّ سراباً. وقد أكد باسترناك في هذه الرواية النزعة الإنسانية ورفض العنف. ولم تكن الرواية لتمس النظام السوفيتي في جوهره، بل تمس بعض الجوانب التطبيقية فيه، إلا أنَّ اتحاد الكتاب السوفيت قرر منع نشر الرواية.

كتب باسترناك في أواخر حياته مسرحية درامية وافَتْه المنية قبل إتمامها وصدرت طبعتها الأولى عام 1969 تحت عنوان «الحسناء العمياء».

يتميز إبداع باسترناك كله بعمق نفسي (سيكولوجي) وفلسفي وإدراك عميق للعالم والروح الإنسانية مع الحفاظ على بساطة في التعبير تعكس عمق الرؤية ووضوحها. وكانت الغنائيةُ السمةَ البارزة في إبداعه، وهي غنائية تقوم على سيل دافق من الأصوات والألفاظ المتناغمة المثقلة بالإحساسات والصور والإيقاعات المتنوعة. لذا أولى باسترناك الإيقاع والموسيقى والوزن الشعري أهمية خاصة، وهو ما كان يميزه عن صديقه ماياكوفسكي الذي انكب على تكسير البيت الألكسندري Alexandrine، وهو بيت شعري مكون من اثني عشر مقطعاً، معتمداً على إيقاعاتٍ جديدة للشعر الروسي.

كان باسترناك يتوجه في قصائده إلى كلِّ فردٍ على حدة. كما تميز بالدقة، وبتداعي الأفكار، وبالنص المعقد. ويتصف معجمه اللغوي بالضخامة والغنى، أما صوره الفنية فقد اتسمت بالتكثيف مما جعل قيمتها التعبيرية والجمالية والغنائية أغنى وأشد وقعاً.

عاش باسترناك سنوات نضجه في المرحلة الستالينية، فسعى جاهداً أن يبتعد عن الصيغ الجاهزة والجمود العقائدي. وقد وضعته السلطة السوفيتية تحت المراقبة منذ مطلع الثلاثينات، وصورته إنساناً معزولاً عن العالم، ذاتياً إلى أبعد الحدود، ثم أطلقت عليه لقب «المرتد» و«عدو الشعب».

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ F.L. Ageenko; M.V. Zarva. Slovar' udarenij (in الروسية). Moscow: Russkij jazyk. p. 686.

- ^ "Pasternak". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "CIA Declassifies Agency Role in Publishing Doctor Zhivago". Central Intelligence Agency. 14 April 2014.

- ^ أ ب «Не читал, но осуждаю!»: 5 фактов о романе «Доктор Живаго» 18:17 23 October 2013, Елена Меньшенина

- ^ "Boris Leonidovich Pasternak Biography". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Christopher Barnes; Christopher J. Barnes; Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (2004). Boris Pasternak: A Literary Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-52073-7.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 137.

- ^ Pasternak (1959), p. 25.

- ^ أ ب Pasternak (1959), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 16.

- ^ Boris Pasternak (1967) "Sister, My Life" Translated by C. Flayderman. Introduction by Robert Payne. Washington Square Press.

- ^ Nina V. Braginskaya (2016). "Olga Freidenberg: A Creative Mind Incarcerated". In Rosie Wyles and Edith Hall (ed.). Women Classical Scholars: Unsealing the Fountain from the Renaissance to Jacqueline de Romilly (PDF). Translated by Zara M. Tarlone. Oxford University Press. pp. 286–312. ISBN 978-0-19-108965-7.

- ^ "BOOKS OF THE TIMES". New York Times. 23 June 1982.

- ^ أ ب Ivinskaya, p. 395.

- ^ أ ب Christopher Barnes (2004). Boris Pasternak: a Literary Biography. Vol. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 166.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Vladimir Markov (1968). Russian Futurism: a History. University of California Press. pp. 229–230.

- ^ Gregory Freidin. "Boris Pasternak". Encyclopedia Britanica. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب Ivinskaya, p. 23.

- ^ John Bayley (5 December 1985). "Big Three". The New York Review of Books. 32. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ^ Zhenia's Childhood and Other Stories. Allison & Busby. 1982. ISBN 978-0-85031-467-0.

- ^ Boris Pasternak (1926). "In Memory of Reissner". marxists.org. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Slater, p. 78.

- ^ Slater, p. 80.

- ^ أ ب ت Ivinskaya, pp. 61–63.

- ^ أ ب Ivinskaya, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 133.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p 135.

- ^ أ ب Ivinskaya, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 75.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 80.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 12, 395, footnote 3.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 12.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 27.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 28.

- ^ أ ب Ivinskaya, p. 86.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 109.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةIvin78 - ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Boris Pasternak: Nobel Prize, Son's Memoirs". English.pravda.ru. 18 December 2003. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 220.

- ^ Slater, p. 402.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 221.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 224.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 232.

- ^ Horst Frenz, ed. (1969). Literature 1901–1967. Nobel Lectures. Amsterdam: Elsevier. (Via "Nobel Prize in Literature 1958 – Announcement". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 24 May 2007.)

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Ivinskaya, pp. 251–261.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةwashingtonpost - ^ Bill Mauldin Beyond Willie and Joe (Library of Congress).

- ^ Hostage of Eternity: Boris Pasternak Archived 27 سبتمبر 2006 at the Wayback Machine (Hoover Institution)

- ^ Conference set on Doctor Zhivago writer (Stanford Report, 28 April 2004)

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 292.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 39.

- ^ Olga Carlisle (Summer–Fall 1960). "Boris Pasternak, The Art of Fiction No. 25". The Paris Review (24).

- ^ أ ب Ivinskaya, pp. 323–326.

- ^ Ivinskaya, p. 332.

- ^ أ ب "OBITUARY: Olga Ivinskaya". The Independent. UK. 13 September 1995. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت "Olga Ivinskaya, 83, Pasternak Muse for 'Zhivago'". New York Times. 13 September 1995. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ "IAU Minor Planet Center". minorplanetcenter.net. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Contents Archived 9 أكتوبر 2006 at the Wayback Machine of Novy Mir magazines (in روسية)

- ^ "Boris Pasternak: The Nobel Prize. Son's memoirs". (Pravda, 18 December 2003)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRFERL.org - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSocial sciences - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtimesonline-292690 - ^ Lutz D. Schmadel (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 294. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

المراجع

- Fleishman, Lazar (1990). Boris Pasternak: The Poet and His Politics. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07905-2.

- Pasternak, Boris (1959). I Remember: Sketches for an Autobiography. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-1-299-79306-4.

- Ivinskaya, Olga (1978). A Captive of Time: My Years with Pasternak. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-00-635336-2..

- Slater, Maya, ed. (2010). Boris Pasternak: Family Correspondence 1921–1960. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-1025-9.

قراءات إضافية

- Conquest, Robert. (1979). The Pasternak Affair: Courage of Genius :A Documentary Report. New York, NY: Octagon Books.

- Maguire, Robert A.; Conquest, Robert (1962). "The Pasternak Affair: Courage of Genius". Russian Review. 21 (3): 292. doi:10.2307/126724. JSTOR 126724.

- Struve, Gleb; Conquest, Robert (1963). "The Pasternak Affair: Courage of Genius". The Slavic and East European Journal. 7 (2): 183. doi:10.2307/304612. JSTOR 304612.

- Paolo Mancosu, Inside the Zhivago Storm: The Editorial Adventures of Pasternak's Masterpiece, Milan: Feltrinelli, 2013

- Mossman, Elliott (ed.) (1982) The Correspondence of Boris Pasternak and Olga Freidenberg 1910 – 1954, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 978-0-15-122630-6

- Peter Finn and Petra Couvee, The Zhivago Affair: The Kremlin, the CIA, and the Battle Over a Forbidden Book, New York: Pantheon Books, 2014

- Paolo Mancosu, Zhivago's Secret Journey: From Typescript to Book, Stanford: Hoover Press, 2016

- Anna Pasternak, Lara: The Untold Love Story and the Inspiration for Doctor Zhivago, Ecco, 2017; ISBN 978-0-06-243934-5.

- Paolo Mancosu, Moscow has Ears Everywhere: New Investigations on Pasternak and Ivinskaya, Stanford: Hoover Press, 2019

وصلات خارجية

- Works by or about بوريس پاسترناك at Internet Archive

- Free scores by بوريس پاسترناك at the International Music Score Library Project

- Read Pasternak's interview with The Paris Review Summer-Fall 1960 No. 24

- بوريس پاسترناك on Nobelprize.org

- Pasternak profile at Poets.org

- PBS biography of Pasternak

- Register of the Pasternak Family Papers at the Hoover Institution Archives

- profile and images at the Pasternak Trust

- pp. 36–39: Pasternak as a student at Marburg University, Germany

- Boris Pasternak poetry

- The Poems by Boris Pasternak (English)

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- Articles with روسية-language sources (ru)

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Nobelprize template using Wikidata property P8024

- بوريس پاسترناك

- مواليد 1890

- وفيات 1960

- حائزو جائزة نوبل في الأدب

- حائزو جائزة نوبل سوڤييت

- حائزو جائزة نوبل يهود

- كتاب من موسكو

- أشخاص من محافظة موسكو

- كتاب من الامبراطورية الروسية

- مترجمون روس في القرن 20

- ناشطون مناهضون للإعدام

- شعراء مسيحيون

- متحولون من اليهودية إلى الأرثوذكسية الشرقية

- مترجمو الروسية-الإنگليزية

- مترجمو الروسية-الفرنسية

- شعراء يهود

- كتاب يهود

- شعراء الامبراطورية الروسية

- شعراء الحرب العالمية الأولى روس

- روائيون من الامبراطورية الروسية

- مترجمون من الامبراطورية الروسية

- يهود الامبراطورية الروسية

- وفيات بسرطان الرئة

- وفيات بالسرطان في الاتحاد السوڤيتي

- منشقون سوڤييت

- كتاب قصص قصيرة سوڤييت

- روائيون سوڤييت

- كتاب سوڤييت

- كتاب القرن 20

- كتاب الحداثة

- تولستويون

- مترجمون من الأرمينية

- مترجمون من التشيكية

- مترجمون من الفرنسية

- مترجمون من الجورجية

- مترجمون من المجرية

- مترجمون من الألمانية

- مترجمون من الپولندية

- مترجمون من الإسپانية

- مترجمون من الأوكرانية

- مترجمو وليام شيكسپير

- مترجمون من الروسية

- مترجمو الروسية-الأوكرانية

- شعراء الحرب العالمية الثانية

- عازفو پيانو كلاسيكيون يهود

- مترجمو يوهان ڤولفگانگ فون گوته