نيكوبول، أوكرانيا

Nikopol

Нікополь | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الإحداثيات: 47°34′N 34°24′E / 47.567°N 34.400°E | |||

| Country | |||

| Oblast | |||

| Raion | |||

| Founded | 1639 | ||

| City status | 1915 | ||

| المساحة | |||

| • الإجمالي | 59 كم² (23 ميل²) | ||

| المنسوب | 70 m (230 ft) | ||

| التعداد (2022) | |||

| • الإجمالي | 105٬160 | ||

| • الكثافة | 2٬764/km2 (7٬160/sq mi) | ||

| Postal code | 53200—53239 | ||

| مفتاح الهاتف | +380-5662 | ||

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www | ||

| |||

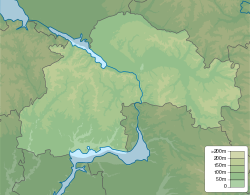

Nikopol (أوكرانية: Ні́кополь, تـُنطق [ˈn⁽ʲ⁾ikopolʲ](![]() استمع)) is a city and municipality (hromada)[1] in Nikopol Raion in the south of Ukraine, on the right bank of the Dnieper River, about 63 km south-east of Kryvyi Rih and 48 km south-west of Zaporizhzhia. Population: 105,160 (2022 estimate).[2]

استمع)) is a city and municipality (hromada)[1] in Nikopol Raion in the south of Ukraine, on the right bank of the Dnieper River, about 63 km south-east of Kryvyi Rih and 48 km south-west of Zaporizhzhia. Population: 105,160 (2022 estimate).[2]

Nikopol is the fourth-most populous city in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. Located on a cape by the Kakhovka reservoir, Nikopol is a powerful industrial city which has several pipe producing factories, such as the Interpipe corporation, and steel rolling mills, such as the factory of ferroalloys.

Formerly the settlement served as one of the capital cities of the Zaporizhian Sich and was known as one of the main crossings over the Dnieper.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

General information

Renamed by the Russian Empire into Slaviansk and later Nikopol (after باليونانية قديمة: Νικόπολις), the city has a rich preceding history. Between 1638–1652, it was the settlement of Mykytyn Rih (أوكرانية: Микитин Ріг, literally Mykyta's bend or Mykyta's horn), the capital of the Zaporizhian Sich. It was one of the main crossings over the Dnieper.

The 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica gave the following description of Nikopol: "It was formerly called Nikitin Rog, and occupies an elongated peninsula between two arms of the Dnieper at a point where its banks are low and marshy, and has been for centuries one of the places where the middle Dnieper can most conveniently be crossed."[3]

In 1900, its 21,282 inhabitants were Ukrainians, Jews and Mennonites, who carry on agriculture and shipbuilding.[بحاجة لمصدر] The old Sich, or fortified camp of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, brilliantly described in N. V. Gogol's novel Taras Bulba (1834), was situated a little higher up the river. A number of graves in the vicinity recall the battles which were fought for the possession of this important strategic point.

One of the graves, close to the town, contained, along with other Scythian antiquities, a well-known precious vase representing the capture of wild horses. Even now Nikopol, which is situated on the highway from Dnipro to Kherson, is the point where the "salt-highway" of the Chumaks (Ukrainian salt-carriers) to the Crimea crossed the Dnipro. Nikopol is, further, one of the chief places on the lower Dnieper for the export of corn, linseed, hemp and wool.

History

Archaeological excavations

According to archaeological excavations, the city's area was populated as early as the Neolithic epoch in the 4th millennium BCE[4] as evidenced by remnants of a settlement discovered on banks of uk (Mala Kamianka River).[4][5] In burial mounds from the copper-bronze epoch of the 3rd-1st millenniums BCE, were found stone and bronze tools, clay sharp-bottomed ornamental dishes.[4] Also found were burials from the Scythian-Sarmatian period, between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE.[4]

Mykytyn Rih / Mykytyn Sich

In the beginning of 16th century, in the location of modern Nikopol, appeared a river crossing over the Dnieper controlled by Cossacks, called Mykytyn Rih.[4] According to a folk legend, it was established by a Cossack named Mykyta Tsyhan.[4] Under the same name, the crossing is mentioned in the diary of the Holy Roman Empire envoy de (Erich Lassota von Steblau), who visited the Zaporizhian Sich in 1594.[4]

In 1638-1639, Cossacks led by F. Linchai built a fort which was named Mykytyn Sich (أوكرانية: Микитинська Січ).[6][7] In 1652, due to conflict with the Hetman of Zaporizhian Host, Kosh Otaman Fedir Liutay moved the administrative seat to Chortomlyk.[8][7]

By 1648, in the close proximity of today's Nikopol, Mykytyn Sich was built. It is renowned for the location of Bohdan Khmelnytsky being elected as the Hetman of Ukraine, and as where the Khmelnytsky Uprising against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth started. Until 1775, the time of the Sich sacking, it was called "Mykytyn Rih", "Mykytyn Pereviz", or simply "Mykytyne".

The name rih (Ukrainian for horn) was given because the locality rose at a place reminiscing a peninsula, as it was almost surrounded by the Dnieper river (see Kryvyi Rih). Mykytyne was a town of the Kodak Palanka, an administrative division of the Zaporizhian Sich. Later it was renamed into Slovianske and then Nikopol.

Sloviansk / Nikopol

In the 18th century, Grigoriy Potyomkin ordered the building of an Imperial Russian fortress Slaviansk. Eventually the project was scratched. Soon after the liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich in 1782, the settlement was renamed as Nikopol.

During World War II, Nikopol was occupied by the German Army until 18 February 1944. Albert Speer referred to it as the "center of manganese mining", and therefore of vital importance to the German war effort.[9]

The Soviet policy of industrialization created the Kakhovka Reservoir which existed from 1956 to 2023, submerging what could be now the most sacred place of an early distinctly Ukrainian statehood: the lands of the former Zaporizhian Host, with their burial sites.

Until July 2020, Nikopol was incorporated as a city of oblast significance and served as the administrative center of Nikopol Raion, though it did not belong to the raion. In July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, which reduced the number of raions of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast to seven, the city of Nikopol was merged into Nikopol Raion.[10][11]

Just a few kilometres west of the city, the Kosh otaman Ivan Sirko is buried.

Nikopol is one of the largest towns in the region, with a population of 105,160 in 2022. The largest manufacturers include the former Nikopol Tube Plant, established in 1931,[12] which is now divided into smaller plants (e.g. Centravis, Interpipe Niko Tube). The Nikopol Ferroalloy Plant is the largest in Europe and the second largest in the world in the production of Ferromanganese (FeMn) and Ferrosilicomanganese (FeSiMn).

Geography

Climate

| Climate data for Nikopol, Ukraine (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

1.0 (33.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.1 (82.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35.4 (1.39) |

35.1 (1.38) |

33.1 (1.30) |

36.9 (1.45) |

39.4 (1.55) |

56.3 (2.22) |

40.4 (1.59) |

32.1 (1.26) |

38.6 (1.52) |

33.5 (1.32) |

42.0 (1.65) |

39.7 (1.56) |

462.5 (18.21) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.7 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 72.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.3 | 81.4 | 77.1 | 67.1 | 62.8 | 65.3 | 62.0 | 60.2 | 67.7 | 75.2 | 84.1 | 84.7 | 72.7 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[13] | |||||||||||||

Transport links

There is bus station, railway station and river port, which connect the town with other cities.

Nikopol River Port facilitates transportation for the metallurgical industry and travel.[14]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Culture

Sports

Gallery

Monument to goddess Nike

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Nikopol is twinned with:

References

- ^ "Никопольская громада" (in الروسية). Портал об'єднаних громад України.

- ^ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in الأوكرانية and الإنجليزية). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2022.

- ^

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 19 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 692.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 19 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 692. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Nikopol (Нікополь). The History of Cities and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR.

- ^ Demianov, V. Mala Kamianka (МАЛА́ КА́М’ЯНКА). Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine

- ^ Bazhan, O. Nikopol (НІКОПОЛЬ). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine

- ^ أ ب Shcherbak, V. Mykytyn Sich (МИКИТИНСЬКА СІЧ). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine. 2009

- ^ Shcherbak, V. Chortomlyk Sich (ЧОРТОМЛИЦЬКА СІЧ). Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine

- ^ Speer, Albert (1995). Inside the Third Reich. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 430. ISBN 9781842127353.

- ^ "Про утворення та ліквідацію районів. Постанова Верховної Ради України № 807-ІХ". Голос України (in الأوكرانية). 2020-07-18. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- ^ "Нові райони: карти + склад" (in Ukrainian). Міністерство розвитку громад та територій України.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "IНТЕРПАЙП НIКО ТЬЮБ". nikotube.interpipe.biz. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Nikopol". encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 19 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 692.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Official city website Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 uses الأوكرانية-language script (uk)

- CS1 الأوكرانية-language sources (uk)

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2023

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Nikopol, Ukraine

- Zaporozhian Sich historic sites

- Cities in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

- Yekaterinoslav Governorate

- Populated places established in 1639

- Cities of regional significance in Ukraine

- Populated places established in the Russian Empire

- Populated places of Kakhovka Reservoir

- Khmelnytsky Uprising

- Populated places on the Dnieper in Ukraine

- Hromadas of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

- صفحات مع الخرائط