سانت بطرسبرغ

سانت پطرسبورگ

Санкт-Петербург Saint Petersburg | |

|---|---|

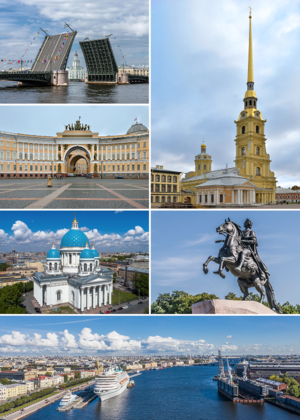

مع عقارب الساعة من أعلى اليسار: جسر القصر مرفوعاً، حصن پطرس وپاڤل على جزيرة زاياتشي، الفارس البرونزي في ميدان مجلس الشيوخ، نهر النيڤا الكبير، كاتدرائية التثليث، و مبنى الأركان العامة. | |

| الكنية: Piter | |

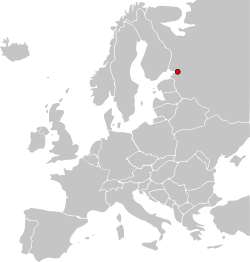

موقع سانت پطرسبورگ | |

| الإحداثيات: 59°56′N 30°20′E / 59.933°N 30.333°E | |

| الدولة | روسيا |

| المنطقة | شمال غرب روسيا |

| مدينة فدرالية | مدينة فدرالية |

| الحكومة | |

| • عمدة | ڤالنتينا ماتڤيينكو |

| المساحة | |

| • المدينة | 606 كم² (234 ميل²) |

| أعلى منسوب | 175 m (574 ft) |

| أوطى منسوب | 3 m (10 ft) |

| التعداد (تعداد 2002 ) | |

| • المدينة | 4٬661٬219 |

| • الكثافة | 3٬330/km2 (8٬600/sq mi) |

| • العمرانية | 6 million |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+3 (MSK) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+4 (MSD) |

| Postal code | 190000–199406 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | +7 812 |

| لوحات السيارات | 78 or 98 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.gov.spb.ru |

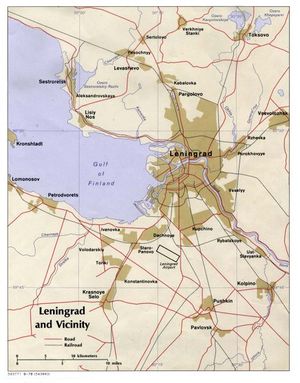

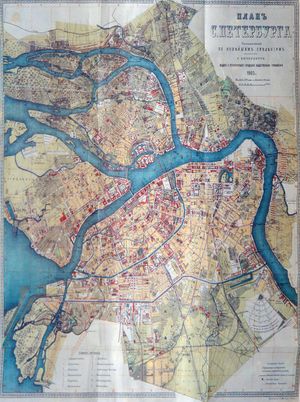

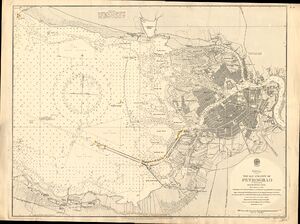

سانت پطرسبورگ (بالروسية: Санкт-Петербу́рг)، والتي كانت تعرف سابقاً باسم لنينگراد (Ленингра́д في 1924-1991) وباسم پيتروگراد (Петрогра́д في 1914-1924)، هي مدينة روسية تقع في شمال غرب روسيا في دلتا نهر نيڤا، شرق خليج فنلندا، في بحر البلطيق.

سانت بطرسبرج ثانية كبريات مدن روسيا، كانت تسمى لنينگراد، عدد سكانها 4,468,000 نسمة، وعدد سكان منطقتها الحضرية 5,020,000 نسمة. هي أحد أهم الموانئ الروسية. تقع المدينة عند مصب نهر النيفا في خليج فنلندا على دائرة العرض 60° شمالاً. موقعها الشماليّ يجعل ساعات النهار قصيرة في فصل الشتاء. أما في فصل الصيف، فإن ساعات النهار تطول وتكون لياليها بيضاء لمدة ثلاثة أسابيع تبدأ من شهر يوليو، فلا يعمها الظلام الكامل أبدًا. كانت سانت بطرسبرج أولى المدن التي خُطِّطت على الطراز الغربي في روسيا، وهي ذات شوارع عريضة وميادين عديدة ومتنزهات واسعة، وبها العديد من المتاحف الفنية والتاريخية والمسارح. وفي القرن الثامن عشر، شيَّد فيها القياصرة قصورًا فخمة أجملها القصر الشتوي المعروف حاليًا باسم الهرميتاج. عدد سكانها 4661219 نسمة (2002)، وتعتبر ثاني أكبر مدينة روسية، ورابع أكبر مدن أوروبا. وهي مركز ثقافي أوروبي هام، كما بها أهم موانئ روسيا في بحر البلطيق. ومساحتها 606 كم2.

The city was founded by Tsar Peter the Great on 27 May 1703 on the site of a captured Swedish fortress, and was named after the apostle Saint Peter.[1] In Russia, Saint Petersburg is historically and culturally associated with the birth of the Russian Empire and Russia's entry into modern history as a European great power.[2] It served as a capital of the Tsardom of Russia, and the subsequent Russian Empire, from 1712 to 1918 (being replaced by Moscow for a short period of time between 1728 and 1730).[3] After the October Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks moved their government to Moscow.[4] The city was renamed Leningrad after Lenin's death in 1924. It was the site of the siege of Leningrad during the Second World War, the most lethal siege in history.[5] In June 1991, only a few months before the Belovezha Accords and the dissolution of the USSR, voters supported restoring the city's original appellation in a city-wide referendum.[6]

As Russia's cultural centre,[7] Saint Petersburg received over 15 million tourists in 2018.[8][9] It is considered an important economic, scientific, and tourism centre of Russia and Europe. In modern times, the city has the nickname of being "the Northern Capital of Russia" and is home to notable federal government bodies such as the Constitutional Court of Russia and the Heraldic Council of the President of the Russian Federation. It is also a seat for the National Library of Russia and a planned location for the Supreme Court of Russia, as well as the home to the headquarters of the Russian Navy, and the Western Military District of the Russian Armed Forces. The Historic Centre of Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments constitute a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Saint Petersburg is home to the Hermitage, one of the largest art museums in the world, the Lakhta Center, the tallest skyscraper in Europe, and was one of the host cities of the 2018 FIFA World Cup and the UEFA Euro 2020.

اسم المكان

While not originally named for Tsar Peter the Great, during World War I the city was changed from the Germanic "Petersburg" to "Petrograd" in his honour |

The name day of Peter I falls on 29 June, when the Russian Orthodox Church observes the memory of apostles Peter and Paul. The consecration of the small wooden church in their names (its construction began at the same time as the citadel) made them the heavenly patrons of the Peter and Paul Fortress, while Saint Peter at the same time became the eponym of the whole city. When in June 1703 Peter the Great renamed the site after Saint Peter, he did not issue a naming act that established an official spelling; even in his own letters he used diverse spellings, such as Санктьпетерсьбурк (Sanktpetersburk), emulating German Sankt Petersburg, and Сантпитербурх (Santpiterburkh), emulating Dutch Sint-Pietersburgh, as Peter was multilingual and a Hollandophile. The name was later normalized and russified to Санкт-Петербург.[10][11][12]

A former spelling of the city's name in English was Saint Petersburgh. This spelling survives in the name of a street in the Bayswater district of London, near St Sophia's Cathedral, named after a visit by the Tsar to London in 1814.[13]

A 14- to 15-letter-long name, composed of the three roots, proved too cumbersome, and many shortened versions were used. The first General Governor of the city Menshikov is maybe also the author of the first nickname of Petersburg which he called Петри (Petri). It took some years until the known Russian spelling of this name finally settled. In 1740s Mikhail Lomonosov uses a derivative of باليونانية: Πετρόπολις (Петрополис, Petropolis) in a Russified form Petropol' (Петрополь). A combo Piterpol (Питерпол) also appears at this time.[14] In any case, eventually the usage of prefix "Sankt-" ceased except for the formal official documents, where a three-letter abbreviation "СПб" (SPb) was very widely used as well.

In the 1830s Alexander Pushkin translated the "foreign" city name of "Saint Petersburg" to the more Russian Petrograd (روسية: Петроград; النطق الروسي: [pʲɪtrɐˈgrat])[أ] in one of his poems. However, it was only on 31 August [ن.ق. 18 August] 1914, after the war with Germany had begun, that Tsar Nicholas II renamed the city Petrograd in order to expunge the German words Sankt and Burg.[15] Since the prefix "Saint" was omitted,[16] this act also changed the eponym and the "patron" of the city from Saint Peter to Peter the Great, its founder.[12] On 26 January 1924, shortly after the death of Vladimir Lenin, it was renamed to Leningrad (روسية: Ленинград; النطق الروسي: [lʲɪnʲɪnˈgrat]), meaning 'Lenin City'. On 6 September 1991, the original name, Sankt-Peterburg, was returned by citywide referendum. Today, in English the city is known as Saint Petersburg. Local residents often refer to the city by its shortened nickname, Piter (روسية: Питер; النطق الروسي: [ˈpʲitʲɪr]).

After the October Revolution the name Red Petrograd (Красный Петроград, Krasny Petrograd) was often used in newspapers and other prints until the city was renamed Leningrad in January 1924.

The referendum on restoring the historic name was held on 12 June 1991, with 55% of voters supporting "Saint Petersburg" and 43% supporting "Leningrad".[6] The turnout was 65%[بحاجة لمصدر]. Renaming the city Petrograd was not an option. This change officially took effect on 6 September 1991.[17] Meanwhile, the oblast whose administrative center is also in Saint Petersburg is still named Leningrad.

Having passed the role of capital to Petersburg, Moscow never relinquished the title of "capital", being called pervoprestolnaya ('first-throned') for 200 years. An equivalent name for Petersburg, the "Northern Capital", has re-entered usage today since several federal institutions were recently moved from Moscow to Saint Petersburg. Solemn descriptive names like "the city of three revolutions" and "the cradle of the October revolution" used in the Soviet era are reminders of the pivotal events in national history that occurred here. Petropolis is a translation of a city name to Greek, and is also a kind of descriptive name: Πέτρ- is a Greek root for 'stone', so the "city from stone" emphasizes the material that had been forcibly made obligatory for construction from the first years of the city[14] (a modern Greek translation is Αγία Πετρούπολη, Agia Petroupoli).[18][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

Saint Petersburg has been traditionally called the "Window to Europe" and the "Window to the West" by the Russians.[19][20] The city is the northernmost metropolis with more than 1 million people in the world, and is also often described as the "Venice of the North" or the "Russian Venice" due to its many water corridors, as the city is built on swamp and water. Furthermore, it has strongly Western European-inspired architecture and culture, which is combined with the city's Russian heritage.[21][22][23] Another nickname of Saint Petersburg is "The City of the White Nights" because of a natural phenomenon which arises due to the closeness to the polar region and ensures that in summer the night skies of the city do not get completely dark for a month.[24][25] The city is also often called the "Northern Palmyra", due to its extravagant architecture.[26]

تاريخ

مقالة مفصلة: تاريخ سانت پطرسبورگ

مقالة مفصلة: تاريخ سانت پطرسبورگ

العصر الإمبراطوري (1703–1917)

Swedish colonists built Nyenskans, a fortress at the mouth of the Neva River in 1611, which was later called Ingermanland. This area was inhabited by a Finnic tribe of Ingrians. The small town of Nyen grew up around the fort.

أسس سانت پطرسبورگ القيصر بطرس الأول في 27 مايو، 1703 "كنافذة مطلة على أوروبا"، وكانت عاصمة البلاد في أثناء قيام الإمبراطورية الروسية حتى 1918.

هذه المدينة أنشأها بطرس الأول الكبير عام 1703م لتكون نافذة تطلّ على أوروبا وتنقل الثقافة والمعرفة الأوروبية لبلاده. أدى الأوروبيون دورًا بارزًا في تخطيطها، وأصبحت المدينة عاصمة الإمبراطورية ومركزها الثقافي والاجتماعيّ.

أدت سانت بطرسبرج دورًا بارزًا في أهم أحداث تاريخ روسيا. قامت بها ثورة فاشلة ضد نقولا الأول عام 1825م. وفي عام 1881م، قامت مجموعة من الثوار باغتيال ألكسندر الثاني. وفي مطلع عام 1905، قام جند نِقولا الثاني بقتل مئات المتظاهرين العزَّل أمام القصر الشتوي. وقد أدت المجزرة التي عُرفت باسم الأحد الدموي إلى ثورة عام 1905.

تغيَّر اسم المدينة إلى پتروگراد عام 1914، ونقلت العاصمة إلى موسكو عام 1918 بعد نجاح الثورة البلشفية وتكوين حكومة جديدة برئاسة لينين. وفي عام 1934م، تغيَّر اسم المدينة إلى "لنينگراد" بعد وفاة لينين، وذلك إحياءً لذكراه.

Revolution of 1905 began in Saint Petersburg and spread rapidly into the provinces.

On 1 September 1914, after the outbreak of World War I, the Imperial government renamed the city Petrograd,[15] meaning "Peter's City", to remove the German words Sankt and Burg.

الثورة والعهد السوڤيتي (1917–1941)

In March 1917, during the February Revolution Nicholas II abdicated for himself and on behalf of his son, ending the Russian monarchy and over three hundred years of Romanov dynastic rule.

On 7 November [ن.ق. 25 October] 1917, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, stormed the Winter Palace in an event known thereafter as the October Revolution, which led to the end of the social-democratic provisional government, the transfer of all political power to the Soviets, and the rise of the Communist Party.[27] After that the city acquired a new descriptive name, "the city of three revolutions",[28] referring to the three major developments in the political history of Russia of the early 20th century.

In September and October 1917, German troops invaded the West Estonian archipelago and threatened Petrograd with bombardment and invasion. On 12 March 1918, Lenin transferred the government of Soviet Russia to Moscow, to keep it away from the state border. During the Russian Civil War, in mid-1919 Russian anti-communist forces with the help of Estonians attempted to capture the city, but Leon Trotsky mobilized the army and forced them to retreat back to Estonia.

On 26 January 1924, five days after Lenin's death, Petrograd was renamed Leningrad. Later many streets and other toponyms were renamed accordingly, with names in honour of communist figures replacing historic names given centuries before. The city has over 230 places associated with the life and activities of Lenin. Some of them were turned into museums,[29] including the cruiser Aurora—a symbol of the October Revolution and the oldest ship in the Russian Navy.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the poor outskirts were reconstructed into regularly planned boroughs. Constructivist architecture flourished around that time. Housing became a government-provided amenity; many "bourgeois" apartments were so large that numerous families were assigned to what were called "communal" apartments (kommunalkas). By the 1930s, 68% of the population lived in such housing under very poor conditions. In 1935, a new general plan was outlined, whereby the city should expand to the south. Constructivism was rejected in favour of a more pompous Stalinist architecture. Moving the city centre further from the border with Finland, Stalin adopted a plan to build a new city hall with a huge adjacent square at the southern end of Moskovsky Prospekt, designated as the new main street of Leningrad. After the Winter (Soviet-Finnish) war in 1939–1940, the Soviet–Finnish border moved northwards. Nevsky Prospekt with Palace Square maintained the functions and the role of a city centre.

In December 1931, Leningrad was administratively separated from Leningrad Oblast. At that time it included the Leningrad Suburban District, some parts of which were transferred back to Leningrad Oblast in 1936 and turned into Vsevolozhsky District, Krasnoselsky District, Pargolovsky District and Slutsky District (renamed Pavlovsky District in 1944).[30]

During the Soviet era, many historic architectural monuments of the previous centuries were destroyed by the new regime for ideological reasons. While that mainly concerned churches and cathedrals, some other buildings were also demolished.[31][32][33]

On 1 December 1934, Sergey Kirov, the Bolshevik leader of Leningrad, was assassinated under suspicious circumstances, which became the pretext for the Great Purge.[34] In Leningrad, approximately 40,000 were executed during Stalin's purges.[35]

الحرب العالمية الثانية (1941–1945)

مقالة مفصلة: حصار لنينگراد

مقالة مفصلة: حصار لنينگراد

وقد تعرضت المدينة للحصار الألماني في أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية لمدة ثلاثة أعوام. وبالرغم من موت مليون شخص من سكانها جوعًا، وتحطيم جزء كبير منها، فإنها لم تستسلم للجيوش الألمانية.

بعد الحرب

وفي نهاية الثمانينيات، ضعفت قبضة الشيوعيين الحديدية على الاتحاد السوفييتي. وقد كسب المناهضون للشيوعية انتخابات 1990م وسيطروا على المدينة. وفي عام 1991م، تغير اسم المدينة من جديد إلى سانت بطرسبرج.

الجغرافيا

The area of Saint Petersburg city proper is 605.8 km2 (233.9 square miles). The area of the federal subject is 1,439 km2 (556 sq mi), which contains Saint Petersburg proper (consisting of eighty-one municipal okrugs), nine municipal towns – (Kolpino, Krasnoye Selo, Kronstadt, Lomonosov, Pavlovsk, Petergof, Pushkin, Sestroretsk, Zelenogorsk) – and twenty-one municipal settlements.

Petersburg is on the middle taiga lowlands along the shores of the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland, and islands of the river delta. The largest are Vasilyevsky Island (besides the artificial island between Obvodny canal and Fontanka, and Kotlin in the Neva Bay), Petrogradsky, Dekabristov and Krestovsky. The latter together with Yelagin and Kamenny Island are covered mostly by parks. The Karelian Isthmus, North of the city, is a popular resort area. In the south, Saint Petersburg crosses the Baltic-Ladoga Klint and meets the Izhora Plateau.

The elevation of Saint Petersburg ranges from the sea level to its highest point of 175.9 m (577 ft) at the Orekhovaya Hill in the Duderhof Heights in the south. Part of the city's territory west of Liteyny Prospekt is no higher than 4 m (13 ft) above sea level, and has suffered from numerous floods. Floods in Saint Petersburg are triggered by a long wave in the Baltic Sea, caused by meteorological conditions, winds and shallowness of the Neva Bay. The five most disastrous floods occurred in 1824 (4.21 m or 13 ft 10 in above sea level, during which over 300 buildings were destroyed[ب]); 1924 (3.8 m, 12 ft 6 in); 1777 (3.21 m, 10 ft 6 in); 1955 (2.93 m, 9 ft 7 in); and 1975 (2.81 m, 9 ft 3 in). To prevent floods, the Saint Petersburg Dam has been constructed.[36]

Since the 18th century, the city's terrain has been raised artificially, at some places by more than 4 m (13 ft), making mergers of several islands, and changing the hydrology of the city. Besides the Neva and its tributaries, other important rivers of the federal subject of Saint Petersburg are Sestra, Okhta and Izhora. The largest lake is Sestroretsky Razliv in the north, followed by Lakhtinsky Razliv, Suzdal Lakes, and other smaller lakes.

Due to its northerly location at c. 60° N latitude the day length in Petersburg varies across seasons, ranging from 5 hours 53 minutes to 18 hours 50 minutes. A period from mid-May to mid-July during which twilight may last all night is called the white nights.

Saint Petersburg is about 165 km (103 miles) from the border with Finland, connected to it via the M10 highway (E18), along which there is also a connection to the historic city of Vyborg.

المناخ

Under the Köppen climate classification, Saint Petersburg is classified as Dfb, a humid continental climate. The distinct moderating influence of Baltic Sea cyclones results in warm, humid, and short summers and long, moderately cold wet winters. The climate of Saint Petersburg is close to that of Helsinki, although slightly more continental (i.e. colder in winter and warmer in summer) because of its more eastern location, while slightly less continental than that of Moscow.

The average maximum temperature in July is 23 °C (73 °F), and the average minimum temperature in February is −8.5 °C (16.7 °F); an extreme temperature of 37.1 °C (98.8 °F) occurred during the 2010 Northern Hemisphere summer heat wave. A winter minimum of −35.9 °C (−32.6 °F) was recorded in 1883. The average annual temperature is 5.8 °C (42.4 °F). The Neva River within the city limits usually freezes up in November–December and break-up occurs in April. From December to March there are 118 days on average with snow cover, which reaches an average snow depth of 19 cm (7.5 in) by February.[37] The frost-free period in the city lasts on average for about 135 days. Despite St. Petersburg's northern location, its winters are warmer than Moscow's due to the Gulf of Finland and some Gulf Stream influence from Scandinavian winds that can bring temperature slightly above freezing. The city also has a slightly warmer climate than its suburbs. Weather conditions are quite variable all year round.[38][39]

Average annual precipitation varies across the city, averaging 660 mm (26 in) per year and reaching maximum in late summer. Due to the cool climate, soil moisture is almost always high because of lower evapotranspiration. Air humidity is 78% on average, and there are, on average, 165 overcast days per year.

| أخفمتوسطات الطقس لسانت پطرسبورگ | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| العظمى القياسية °C (°F) | 8.6 (47) | 10.2 (50) | 14.9 (59) | 25.3 (78) | 30.9 (88) | 34.6 (94) | 34.3 (94) | 33.5 (92) | 30.4 (87) | 21.0 (70) | 12.3 (54) | 10.9 (52) | 34٫6 (94) |

| متوسط العظمى °م (°ف) | -4.8 (23) | -4.6 (24) | 0.0 (32) | 7.4 (45) | 14.7 (58) | 19.4 (67) | 22.0 (72) | 20.1 (68) | 14.5 (58) | 7.7 (46) | 1.6 (35) | -2.5 (28) | 8٫1 (47) |

| متوسط الصغرى °م (°ف) | -10.5 (13) | -10.6 (13) | -6.9 (20) | -0.2 (32) | 5.7 (42) | 10.8 (51) | 13.9 (57) | 12.5 (55) | 7.9 (46) | 2.8 (37) | -2.4 (28) | -7.3 (19) | 1٫4 (35) |

| الصغرى القياسية °م (°F) | -35.9 (-33) | -35.2 (-31) | -29.9 (-22) | -21.8 (-7) | -6.6 (20) | 0.1 (32) | 4.9 (41) | 1.3 (34) | -3.1 (26) | -12.9 (9) | -22.2 (-8) | -34.4 (-30) | −35٫9 (−33) |

| هطول الأمطار mm (بوصة) | 37 (1.5) | 30 (1.2) | 34 (1.3) | 33 (1.3) | 37 (1.5) | 57 (2.2) | 77 (3) | 80 (3.1) | 69 (2.7) | 66 (2.6) | 55 (2.2) | 50 (2) | 625 (24٫6) |

| المصدر: Pogoda.ru.net[37] 29.07.2007 | |||||||||||||

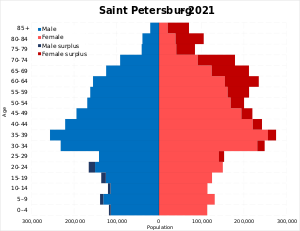

السكان

Saint Petersburg is the second largest city in Russia. As of the 2021 Census,[40] the federal subject's population is 5,601,911 or 3.9% of the total population of Russia; up from 4,879,566 (3.4%) recorded in the 2010 Census,[41] and up from 5,023,506 recorded in the 1989 Census.[42] Over 6.4 million people reside in the metropolitan area.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 1٬264٬920 | — |

| 1926 | 1٬590٬770 | +0.79% |

| 1939 | 3٬191٬304 | +5.50% |

| 1959 | 3٬321٬196 | +0.20% |

| 1970 | 3٬949٬501 | +1.59% |

| 1979 | 4٬588٬183 | +1.68% |

| 1989 | 5٬023٬506 | +0.91% |

| 2002 | 4٬661٬219 | −0.57% |

| 2010 | 4٬879٬566 | +0.57% |

| 2021 | 5٬601٬911 | +1.26% |

| المصدر: بيانات التعداد | ||

Vital statistics for 2022:[43][44]

- Births: 50,663 (9.4 per 1,000)

- Deaths: 65,137 (12.1 per 1,000)

Total fertility rate (2022):[45]

1.28 children per woman

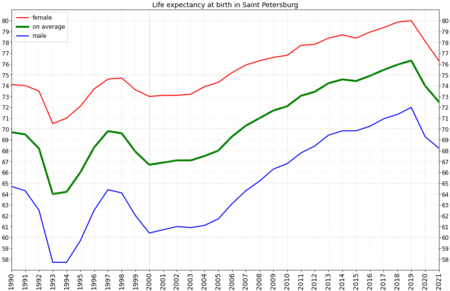

Life expectancy (2021):[46]

Total — 72.51 years (male — 68.23, female — 76.30)

التركيبة العرقية لسانت بطرسبورج

| العرق | السنة | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939[47] | 1959[48] | 1970[49] | 1979[50] | 1989[51] | 2002[52] | 2010[52] | 2021[53] | |||||||||

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population1 | % | |

| Russians | 2,775,979 | 86.9 | 2,951,254 | 88.9 | 3,514,296 | 89.0 | 4,097,629 | 89.7 | 4,448,884 | 89.1 | 3,949,623 | 92.0 | 3,908,753 | 92.5 | 4,275,058 | 90.6 |

| Ukrainians | 54,660 | 1.7 | 68,308 | 2.1 | 97,109 | 2.5 | 117,412 | 2.6 | 150,982 | 3.0 | 87,119 | 2.0 | 64,446 | 1.5 | 29,353 | 0.6 |

| Tatars | 31,506 | 1.0 | 27,178 | 0.8 | 32,851 | 0.8 | 39,403 | 0.9 | 43,997 | 0.9 | 35,553 | 0.8 | 30,857 | 0.7 | 20,286 | 0.4 |

| Azerbaijanis | 385 | - | 855 | - | 1,576 | - | 3,171 | 0.1 | 11,804 | 0.2 | 16,613 | 0.4 | 17,717 | 0.4 | 16,406 | 0.3 |

| Belarusians | 32,353 | 1.0 | 47,004 | 1.4 | 63,799 | 1.6 | 81,575 | 1.8 | 93,564 | 1.9 | 54,484 | 1.3 | 38,136 | 0.9 | 15,545 | 0.3 |

| Armenians | 4,615 | 0.1 | 4,897 | 0.1 | 6,628 | 0.2 | 7,995 | 0.2 | 12,070 | 0.2 | 19,164 | 0.4 | 19,971 | 0.5 | 14,737 | 0.3 |

| Uzbeks | 238 | - | - | - | 1,678 | - | 1,883 | - | 7,927 | 0.2 | 2,987 | 0.1 | 20,345 | 0.5 | 12,181 | 0.3 |

| Tajiks | 61 | - | - | - | 361 | - | 473 | - | 1,917 | - | 2,449 | 0.1 | 12,072 | 0.3 | 9,573 | 0.2 |

| يهود | 201,542 | 6.3 | 168,641 | 5.1 | 162,525 | 4.1 | 142,779 | 3.1 | 106,469 | 2.1 | 36,570 | 0.9 | 24,132 | 0.6 | 9,205 | 0.2 |

| Others | 89,965 | 2.8 | 53,059 | 1.6 | 68,678 | 1.7 | 76,228 | 1.7 | 113,135 | 2.3 | 88,661 | 2.1 | 90,310 | 2.1 | 277,297 | 6.7 |

| Total | 3,191,304 | 100 | 3,321,196 | 100 | 3,949,501 | 100 | 4,588,183 | 100 | 5,023,506 | 100 | 4,661,219 | 100 | 4,879,566 | 100 | 5,601,911 | 100 |

| 1884,678 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group. | ||||||||||||||||

During the 20th century, the city experienced dramatic population changes. From 2.4 million residents in 1916, its population dropped to less than 740,000 by 1920 during the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Russian Civil War. The minorities of Germans, Poles, Finns, Estonians and Latvians were almost completely transferred from Leningrad during the 1930s.[54] From 1941 to the end of 1943, population dropped from 3 million to less than 600,000, as people died in battles, starved to death or were evacuated during the Siege of Leningrad. Some evacuees returned after the siege, but most influx was due to migration from other parts of the Soviet Union. The city absorbed about 3 million people in the 1950s and grew to over 5 million in the 1980s. From 1991 to 2006 the city's population decreased to 4.6 million, while the suburban population increased due to privatization of land and massive move to suburbs. Based on the 2010 census results the population is over 4.8 million.[55][56] For the first half of 2007, the birth rate was 9.1 per 1000[57] and remained lower than the death rate (until 2012[58]); people over 65 constitute more than twenty percent of the population; and the median age is about 40 years.[59] Since 2012 the birth rate became higher than the death rate.[58] But in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic caused a drop in birth rate, and the city population decreased to 5,395,000 people.[60]

الدين

According to various opinion polls, more than half of the residents of Saint Petersburg "believe in God" (up to 67% according to VTsIOM data for 2002).

Among the believers, the overwhelming majority of the residents of the city are Orthodox (57.5%), followed by small minority communities of Muslims (0.7%), Protestants (0.6%), and Catholics (0.5%), and Buddhists (0.1%).[61]

In total, roughly 59% of the population of the city is Christian, of which over 90% are Orthodox.[61] Non-Abrahamic religions and other faiths are represented by only 1.2% of the total population.[61]

There are 268 communities of confessions and religious associations in the city: the Russian Orthodox Church (130 associations), Pentecostalism (23 associations), the Lutheranism (19 associations), Baptism (13 associations), as well as Old Believers, Roman Catholic Church, Armenian Apostolic Church, Georgian Orthodox Church, Seventh-day Adventist Church, Judaism, Buddhist, Muslim, Bahá'í and others.[61]

229 religious buildings in the city are owned or run by religious associations. Among them are architectural monuments of federal significance. The oldest cathedral in the city is the Peter and Paul Cathedral, built between 1712 and 1733, and the largest is the Kazan Cathedral, completed in 1811.

الحكومة

Saint Petersburg is a federal subject of Russia (a federal city).[64] The political life of Saint Petersburg is regulated by the Charter of Saint Petersburg adopted by the city legislature in 1998.[65] The superior executive body is the Saint Petersburg City Administration, led by the city governor (mayor before 1996). Saint Petersburg has a single-chamber legislature, the Saint Petersburg Legislative Assembly, which is the city's regional parliament.

According to the federal law passed in 2004, heads of federal subjects, including the governor of Saint Petersburg, were nominated by the President of Russia and approved by local legislatures. Should the legislature disapprove the nominee, the President could dissolve it. The former governor, Valentina Matviyenko, was approved according to the new system in December 2006. She was the only woman governor in the whole of Russia until her resignation on 22 August 2011. Matviyenko stood for elections as member of the Regional Council of Saint Petersburg and won comprehensively with allegations of rigging and ballot stuffing by the opposition. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev has already backed her for the position of Speaker to the Federation Council of the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation and her election qualifies her for that job. After her resignation, Georgy Poltavchenko was appointed as the new acting governor the same day. In 2012, following passage of a new federal law,[66] restoring direct elections of heads of federal subjects, the city charter was again amended to provide for direct elections of governor.[67] On 3 October 2018, Poltavchenko resigned, and Alexander Beglov was appointed acting governor.[68]

Saint Petersburg is also the unofficial but de facto administrative centre of Leningrad Oblast, and of the Northwestern Federal District.[69] The Constitutional Court of Russia moved to Saint Petersburg from Moscow in May 2008.

Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast, being two different federal subjects, share a number of local departments of federal executive agencies and courts, such as court of arbitration, police, FSB, postal service, drug enforcement administration, penitentiary service, federal registration service, and other federal services.

Administrative divisions

| Saint Petersburg is divided into 18 administrative districts: | ||

| Within the boundaries of the districts, there are 111 intra-city municipalities, 81 municipal districts, and 9 cities: (Zelenogorsk, Kolpino, Krasnoe Selo, Kronstadt, Lomonosov, Pavlovsk, Petergof, Pushkin, and Sestroretsk), as well as 21 villages.[70] | ||

الجريمة

الاقتصاد

Saint Petersburg is a major trade gateway, serving as the financial and industrial centre of Russia, with specializations in oil and gas trade; shipbuilding yards; aerospace industry; technology, including radio, electronics, software, and computers; machine building, heavy machinery and transport, including tanks and other military equipment; mining; instrument manufacture; ferrous and nonferrous metallurgy (production of aluminium alloys); chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and medical equipment; publishing and printing; food and catering; wholesale and retail; textile and apparel industries; and many other businesses. It was also home to Lessner, one of Russia's two pioneering automobile manufacturers (along with Russo-Baltic); it was founded by machine tool and boilermaker G.A. Lessner in 1904, with designs by Boris Loutsky, and it survived until 1910.[71]

Ten per cent of the world's power turbines are made there at the LMZ, which built over two thousand turbines for power plants across the world. Major local industries are Admiralty Shipyard, Baltic Shipyard, LOMO, Kirov Plant, Elektrosila, Izhorskiye Zavody; also registered in Saint Petersburg are Sovkomflot, Petersburg Fuel Company and SIBUR among other major Russian and international companies.

The Port of Saint Petersburg has three large cargo terminals, Bolshoi Port Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, and Lomonosov terminal.[بحاجة لمصدر] International cruise liners have been served at the passenger port at Morskoy Vokzal on the south-west of Vasilyevsky Island. In 2008 the first two berths opened at the New Passenger Port on the west of the island.[72] The new passenger terminal is part of the city's "Marine Facade" development project[73] and was due to have seven berths in operation by 2010.[معلومات قديمة]

A complex system of riverports on both banks of the Neva River are interconnected with the system of seaports, thus making Saint Petersburg the main link between the Baltic Sea and the rest of Russia through the Volga–Baltic Waterway.

The Saint Petersburg Mint (Monetny Dvor), founded in 1724, is one of the largest mints in the world, it mints Russian coins, medals and badges. Saint Petersburg is also home to the oldest and largest Russian foundry, Monumentskulptura, which made thousands of sculptures and statues that now grace the public parks of Saint Petersburg and many other cities. Monuments and bronze statues of the Tsars, as well as other important historic figures and dignitaries, and other world-famous monuments, such as the sculptures by Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg, Paolo Troubetzkoy, Mark Antokolsky, and others, were made there.

In 2007, Toyota opened a Camry plant after investing 5 billion roubles (approx. 200 mln dollars) in Shushary, one of the southern suburbs of Saint Petersburg. Opel, Hyundai and Nissan have also signed deals with the Russian government to build their automotive plants in Saint Petersburg. The automotive and auto-parts industry is on the rise there during the last decade.

Saint Petersburg has a large brewery and distillery industry. Known as Russia's "beer capital" due to the supply and quality of local water, its five large breweries account for over 30% of the country's domestic beer production. They include Europe's second-largest brewery Baltika, Vena (both operated by BBH), Heineken Brewery, Stepan Razin (both by Heineken) and Tinkoff brewery (SUN-InBev).

The city's many local distilleries produce a broad range of vodka brands. The oldest ones is LIVIZ (founded in 1897). Among the youngest is Russian Standard Vodka introduced in Moscow in 1998, which opened in 2006 a new $60 million distillery in Petersburg (an area of 30,000 m2 (320,000 sq ft), production rate of 22,500 bottles per hour). In 2007, this brand was exported to over 70 countries.[74]

Saint Petersburg has the second-largest construction industry in Russia, including commercial, housing, and road construction.

In 2006, Saint Petersburg's city budget was 180 billion rubles (about 7 billion US$ at 2006 exchange rates),.[75] The federal subject's Gross Regional Product اعتبارا من 2016[تحديث] was 3.7 trillion Russian rubles (or around US$70 billion), ranked 2nd in Russia, after Moscow[76] and per capita of US$13,000, ranked 12th among Russia's federal subjects,[77] contributed mostly by wholesale and retail trade and repair services (24.7%) as well as processing industry (20.9%) and transportation and telecommunications (15.1%).[78]

Budget revenues of the city in 2009 amounted to 294.3 billion rubles (about 10.044 billion US$ at 2009 exchange rates), expenses – 336.3 billion rubles (about 11.477 billion US$ at 2009 exchange rates). The budget deficit amounted to about 42 billion rubles.[79] (about 1.433 billion US$ at 2009 exchange rates)

In 2015, St. Petersburg was ranked in 4th place economically amongst all federal subjects of the Russian Federation, surpassed only by Moscow, the Tyumen and Moscow Region.[80]

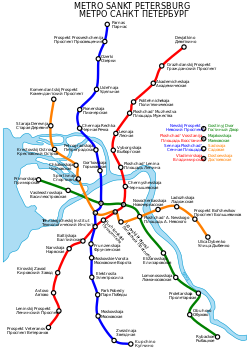

المواصلات

المباني والمعالم

القنوات والجسور

مقالة مفصلة: قائمة جسور سانت پطرسبرگ

مقالة مفصلة: قائمة جسور سانت پطرسبرگ

قصور القياصرة

1 - قصور مدينة بطرسبورگ القديمة – روائع للفن المعماري والذوق الرفيع

يعتبر الجزء القديم لمدينة بطرسبورگ بحد ذاته متحفا للفن المعماري. لقد بنيت المدينة منذ تاسيسها قبل اكثر من 300 سنة لتكون احدى اجمل مدن اوروبا. لذا فأن مباني المدينة القديمة تبهر العين بجمالها ورونقها وفنها المعماري الذي يصعب مشاهدة مثيل له بهذا الحجم في مدينة ثانية.

1 – قصر انيتشكوف – استمر بناء هذا القصر من عام 1741 لغاية عام 1751 . يقع القصر على ضفة قناة فونتانكا بالقرب من نهر نيفا وهو مشيد على طراز الباروكو المتقدم. يشبه شكل القصر من الاعلى حرف " H " الانجليزي. والمبنى الوسطي له يتكون من 3 طوابق يتضمن قاعة كبيرة فيها ثريتان مرتبطة بجناحين متكونين من 3 طوابق ايضا. يغطي المبنى سقف مضلع. واجهة القصر الرئيسية تطل على قناة فانتانكا حيث يقع هنا فناء الاستقبال ومسبح متصل بقناة فانتانكا. اما الواجهة المقابلة فتطل على الحديقة المنتظمة. يتضمن الطابقان الثاني والثالث للجناح الجانبي للقصر كنيسة بيتية زخرفت جدرانها الداخلية ونقشت برسوم وايقونات كثيرة حتى ان ارتفاع الفاصل الايقوني المذهب يصل الى 11 مترا.

في بداية القرن الـ 19 ظهرت في القصر تصاميم وديكورات جديدة وتعتبر القاعة البيضاء اهمها التي تنقسم جدرانها العرضية الى اعمدة اغريقية ثنائية. لقد بقيت هذه القاعة وقاعة الاعمدة الصفراء حتى يومنا هذا على وضعها الاولي.

اتخذ الامبراطور الكسندر الثالث هذا القصر مقرا له حيث غطيت جدران القصر الداخلية بلوحات فنية لرسامين روس واوروبيين. في نهاية القرن الـ 19 وبداية القرن العشرين كان القصر مقرا للامبراطورة ماريا فيودوروفنا.

بعد ثورة اكتوبر عام 1917 حول القصر الى متحف مدينة بطرسبورگ القديمة. القصر حاليا هو قصر ابداعات الشباب.

2 – القصر الصيفي للقيصر بطرس الاكبر – يشبه شكل القصر من الاعلى المستطيل. يتكون المبنى من طابقين. الواجهة مزخرفة ومنقوشة برسوم واشكال جميلة. وتفصل بين نوافذ الطابقين اشكال طينية منحوتة تحكي قصة انتصار روسيا على السويد في حرب الشمال. المدخل الرئيسي للقصر يقع في جهة الحديقة ومزين بتماثيل ونقوش في وسطها رايات النصر وغنائمه.

بالرغم من مرور اكثر من ثلاثة قرون على تشييد القصر الا ان مظهره الخارجي لازال على وضعه وشكله الجميل، ومن احد اسباب ذلك هو انه خلال فترة حكم بطرس الاكبر شيد قصران صيفيان اخران بالقرب من هذا القصر اوسع منه. كما انه بعد الانتهاء من تشييد القصر الصيفي الكبير ليليزافيتا بيتروفنا اهمل هذا القصر عمليا ، مما انقذه من اجراء تقسيمات جديدة عليه في اثناء عمليات الصيانة. كان بطرس الاكبر يحب الاقامة في هذا القصر من الربيع وحتى نهاية الخريف. توجد في كل طابق 7 غرف موزعة على شكل صفين ولا يحتوي القصر على قاعات كبيرة. كسيت جدران الطابق الارضي الداخلية بألواح منقوشة من خشب البلوط، كما ان غرفة المكتب هي الاخرى تحتوي على نقوش يضاهي جمالها نقوش بقية الغرف. اما الطابق الثاني فيحتوي على غرفة المكتب الاخضر حيث توجد نقوش ورسوم مذهبة رائعة وجميلة.

3 – قصر ستروغونوف – شيد هذا القصر خلال اعوام 1752 – 1754 ويعتبر احد اعظم قصور بطرسبورغ وسمي بأسم صاحبه الذي منح المهندس المعماري حرية التصرف بشكل كامل في العمل. يقع القصر في منطقة التقاء قناة مويكا بنهر نيفا. لم يتغير مظهر القصر الخارجي بالرغم من مرور اكثر من 250 سنة على بنائه. واجهة القصر الرئيسية تطل على شارع نيفسكي وفيها اعمدة ثنائية تستند الى قاعدة مزخرفة وفي اعلاها شعار عائلة ستروغونوف الخاص. نوافذ القصر مزخرفة ومنقوشة. في عام 1790 حصلت بعض التغييرات على البناء، حيث شيدت بدلا من الاجنحة الاحادية الطابق اجنحة اوسع وذات ديكورات داخلية على الطراز الكلاسيكي. وتتميز قاعة اللوحات الفنية بجمال وروعة ديكوراتها وتصميمها وكذلك باللوحات التي تحتويها والتي تضاهي في قيمتها الفنية اللوحات المعروضة في الغاليريهات العالمية، كما توجد في القصر قاعات اخرى مثل القاعة العربية والمكتب المعدني. يحتوي القصر على اكثر من 50 غرفة مختلفة الاحجام. بعد عام 1988 تقرر اجراء الترميمات اللازمة على مباني القصر وتسليمه الى ادارة المتحف الروسي.

4 – قصر شوفالوف – يعود هذا القصر الى الكونت ايفان شوفالوف مؤسس اكاديمية الفنون. بني هذا القصر خلال اعوام 1753 – 1756 الذي اعتبر انذاك اجمل واروع المباني في بطرسبورغ. القصر مشيد على طراز باروكو المتقدم. واجهة القصر الامامية جميلة ومنحوتة بدعائم مضلعة فوقها قوصرة شعاعية الشكل جميلة. بالرغم من مرور هذه الفترة الطويلة على انشاء القصر، الا انه مازال احد المعالم المعمارية والتاريخية في المدينة. يستخدم هذا المبنى حاليا كمقر لجمعيات الصداقة الروسية مع الدول الاجنبية.

5 – القصر الرخامي – استمر بناء هذا القصر من عام 1769 وحتى عام 1785 ، وهو اول مبنى في بطرسبورگ تكسى جدرانه الخارجية وبعض جدرانه الداخلية بحجر طبيعي. حيث استخدمت في ذلك انواع مختلفة من الرخام والغرانيت ولهذا اطلق علية اسم القصر " الرخامي ". لقد نجح المهندس المعماري في جمع وظيفتين للمبنى فمن جانب ان القصر مبنى في مدينة على غرار القصور والمباني الاخرى ومن جانب اخر هو بيت ريفي على غرار بيوت النبلاء الريفية في القرن الـ 18 . مباني القصر الشرقية مبنية على شكل حرف " П " اليوناني هذه المباني فصلت عن مباني الجزء الغربي الخدمية بجدار حجري وفناء فيه جنينة. وفي نفس الوقت خصص القسم الغربي من القصر للخدمات ومخادع النوم. لقد كسيت الجدران الخارجية للطابق الارضي من المباني بحجر الغرانيت الاحمر، بينما تمت تكسية الطابقين الثاني والثالث بحجر الرخام الرمادي الفاتح وتفصل بين قطعه قطع صغيرة من الرخام الاحمر والوردي. كان الطابق الارضي للقصر مخصصا للخدمات والمطابخ ومخازن المؤن وكنيسة بيتية. اما الطابق الثاني فكان مخصصا للاستقبال والاحتفالات اما الطابق الثالث فهو مخصص للنوم. اعتمد اسلوب الروكوكو كأساس في بناء القصر حيث يكون لكل قسم كيان منفصل عن البقية وترتبط فيما بينها بقاعات ضيقة صغيرة وممرات وسلالم تربط بين طوابقه الثلاثة.

بعد مرور فترة زمنية وتغير ملكية القصر قرر صاحبه اجراء بعض اعمال الصيانة والتغييرات عليه خاصة تقسيمات الطابق الارضي حيث على اثرها ظهرت قاعة المكتبة والمكتب الانجليزي وقاعة الموسيقى لاقامة امسيات موسيقة وغنائية ومسرحيات، أي تحول القصر الى مركز من المراكز الثقافية في بطرسبورگ .

اجريت على المبنى ترميمات وعمليات صيانة شاملة في ثمانينات القرن الماضي وهو حاليا فرع للمتحف الروسي وتعرض فيه بشكل دائم لوحات واعمال الرسامين والنحات الاجانب اضافة الى اقامة معارض وقتية.

6 – قصر شيريميتوف – يقع هذا القصر على ضفة قناة فونتانكا واكتمل بناؤه عام 1755 . يعتبر القصر من المعالم المعمارية المبنية على طراز باروكو في المدينة. كان القيصر بطرس الاكبر قد اهدى قطعة الارض المقام عليها القصر الى الفيلد مارشال الكونت بوريس شيريميتيف الذي كان من انصاره ورافقه في حملاته وجولاته العديدة. تحتوي الواجهة المركزية على 6 اعمدة كورنثية ثبتت فوقها قوصرة شعاعية الشكل، اما جانبا الواجهة فهي الاخرى محاطة باعمدة فوقها قوصرة مثلثة الشكل.

واجهة القصر الرئيسية تطل على النهر وهي تعبر عن الفن المعماري للقرن الـ 18 . الطابق الارضي من القصر كان مخصصا للخدمات اما الطابق الثاني ففيه غرف وقاعات للاستقبال ومخادع تشكل صفين من الممرات. يتضمن القصر ايضا حديقة فيها كهف صناعي وصومعة وبوابة مزخرفة واماكن عديدة لقضاء الامسيات وشرب الشاي وغير ذلك. اصبح القصر بنهاية القرن الـ 18 مركزا للمسرح والموسيقى في بطرسبورغ .شهد هذا القصر قصة حب بين الكونت نيقولاي شيريميتيف والفلاحة براسكوفيا كوفاليوفا التي انتهت بزواجهما حيث منحت بعد ذلك لقب كونتيسة.

بعد ثورة اكتوبر عام 1917 سلم الكونت شيريميتيف القصر الى السلطات بمحتوياته كاملة وتحول الى متحف.

عاشت في هذا القصر في فترات مختلفة اخرها كان بين اعوام 1944 – 1952 الشاعرة الروسية آنا اخماتوفا حيث اسس في الجناح الذي سكنته متحف شخصي لها. يتضمن القصر ايضا متحفا يتحدث عن تاريخ عائلة شيريميتيف.

7 – قصر ميخائيلوف – هذا القصر كالقلعة بوشر ببنائه عام 1796 بعد وفاة الامبراطورة يكاتيرينا الثانية، حيث كان بافل الاول يطمح الى الاقامة في قصر يملكه بدلا من قصر يكاتيرينا الثانية لكي يشعر بالامان والاطمئنان. اشرف على هندسة القصر اشهر المهندسين المعماريين المعجبين بالفن المعماري للقرون الوسطى. وافق بافل الاول على التصميم الذي كان يتضمن عناصر من قلاع الفرسان في القرون الوسطى اضافة الى الطرز المعمارية للقرن الـ 18 . استمرت عمليات بناء القصر ليل نهار وبدون ايام استراحة وساهم فيها اكثر من 6000 عامل من مختلف المهن حيث انتهت في نهاية عام 1800 .

للوهلة الاولى يبدو ان القصر منيع جدا لكونه محاطا بالمياه من جميع جوانبه ولا يمكن الدخول اليه الا بواسطة الجسر المتحرك فقط، الا ان القيصر بافل الاول قتل في مخدعه بعد 40 يوما فقط من اقامته في هذا القصر القلعة. تعتبر التصاميم الداخلية للقصر من العجائب الفنية، فهي من ناحية تعكس الابهة الامبراطورية ومن ناحية ثانية هو متحف فني للتحفيات القديمة وفنون اوروبا الغربية والفنون الروسية. بعد مقتل بافل الاول انتقلت العائلة القيصرية الى القصر الشتوي ثانية وفي عام 1819 اصبح القصر مقرا لكلية الهندسة. اجريت في عام 1991 ترميمات وصيانة كاملة للقصر وسلم المبنى الى المتحف الوطني الروسي، واقيم امام واجهته الجنوبية تمثال للامبراطور بطرس الاكبر يمتطي حصانه وكان قد انجز عام 1740 .

8 – قصر ماريا – شيد القيصر نيقولاي الاول هذا القصر هدية لابنته ماريا بمناسبة زواجها. اكتمل بناء القصر عام 1844 . يقع القصر في الجهة المقابلة لكاتدرائية اسحق على ضفة قناة يكاتيرينا. كان هدف الامبراطور ان يكون القصر مختلفا عن القصور الاخرى، بحيث يكون نموذجا للرفاهية والاستراحة. ان ما يثير الانتباه كون جناحي القصر غير متساوية وغير متناظرة كما هو معتاد فجناحه الايمن اقصر من جناحه الايسر بـ 52 مترا كما انه مبني بزاوية منفرجة بالنسبة للواجهة الرئيسية المبنية على الطراز الكلاسيكي ليماثل المباني المشيدة على الساحة التي يطل عليها القصر. القاعات وغرف الخدمات قريبة من الطريق اما غرف النوم فهي في الجهة المقابلة بعيدة عن الضوضاء والغبار.

بعد ثورة اكتوبر عام 1917 اصبح القصر مقرا لمؤسسات حزبية مختلفة وخلال الحرب الوطنية العظمى تحول المبنى الى مستشفى عسكري مما تطلب اجراء بعض التعديلات عليه. اجريت على القصر خلال ستينات وسبعينات القرن الماضي ترميمات كاملة وهو حاليا مقر المجلس التشريعي لمدينة بطرسبورگ.

9 – قصر مينشيكوف – شيد هذا القصر بأمر من الكسندر مينشيكوف اول محافظ لمدينة بطرسبورگ واحد المقربين والمناصرين للقيصر بطرس الاكبر. بوشر ببناء القصر عام 1710 وهو اول مبنى حجري في المدينة ويعتبر اضخم مباني المدينة واجملها في عصر القيصر بطرس الاكبر وكان يستخدم للاستقبالات الدبلوماسية الرسمية والاجتماعات.

غرف القصر موزعة على جانبي الممرات ومازال بهو القصر وسلمه ونقوش واجهته التي تستند على صفين من الاعمدة الملساء على وضعها الاولي. لقد اكتشفت في الغرفة المغلفة بخشب البلوط في اثناء عمليات الصيانة، اكتشفت لوحة جدارية تعود للربع الاول من القرن الـ 18 تمثل القيصر بطرس الاكبر كمحارب منتصر. وسابقا كان القصر محاطا بحديقة غناء فيها نوافير عديدة وكهوف صناعية واجنحة مختلفة الا انها ازيلت ولم يبق لها أي اثر.

10 – قصر يوسوبوف – يعتبر هذا القصر من المعالم المعمارية المبنية على الطراز الكلاسيكي وكان في بداية الامر يتكون من طابقين ( منتصف القرن الـ 18 ). تم في ستينات القرن الـ 18 توسيعه وبناء طابق ثالث، حيث تميزت واجهته الرئيسية بـ 6 اعمدة تربط الطابقين السفليين فوقها قوصرة مثلثة الشكل. وفي ثلاثينات القرن الـ 19 تم بناء جناح يتضمن قاعة رخامية واسعة بأعمدة بيضاء. في هذا القصر قتل راسبوتين بديسمبر/كانون الاول عام 1916 .

بعد ثورة اكتوبر عام 1917 تحول المبنى من عام 1919 لغاية 1925 الى متحف اصبح بعدها يسمى " دار المعلم " حاليا يسمى " قصر العاملين في التعليم ". اجريت على المب نى ترميمات وصيانة كاملة استمرت لفترة طويلة فخلال الفترة من 1946 ولغاية عام 1955 تمت ترميمات القاعة الخضراء وقاعة الرقص وبهو الاستقبال والغرف الخاصة والمسرح. ومنذ عام 1987 افتتح هنا مسرح موسيقى الحجرة.

11 – القصر الشتوي - هو المبنى الرئيسي لمتحف الارميتاج. شيد القصر خلال الفترة بين عامي 1754 و1762 . كان اول نموذج لمقر الامبراطور الشتوي وشيد على ضفة قناة زيمنايا في عهد الامبراطور بطرس الاكبر عام 1711 اما النموذج الثاني فكان في مكان مسرح الارميتاج حاليا وشيد خلال الفترة من 1716 – 1719 . في عام 1732 بوشر ببناء القصر الثالث الذي تطل واجهته على نهر نيفا وساحة القصر. وشيد النموذج الرابع المؤقت لقصر الشتاء من الخشب عام 1755 على زاوية شارع نيفسكي وكورنيش نهر مويكا. وبعد اكتمال بناء القصر الشتوي الدائم عام 1762 ازيل المبنى الخشبي. اول من اقام في القصر الحالي كان الامبراطور بطرس الثالث.

ان بناء القصر يوحي بعظمته وفخامته وان تصاميمه الداخلية غنية بزخرفتها ونقوشها الرائعة والبديعة. لقد بقيت واجهة القصر على شكلها الاولي اما التقسيمات الداخلية فأجريت عليها تغييرات عديدة اشرف عليها افضل المهندسين المعماريين الروس والاوروبيين. في عام 1922 اصبح القسم الاكبر من القصر متحفا وفي عام 1945 سلمت كافة المباني الى متحف الارميتاج الذي يعتبر احد اضخم المتاحف في العالم.

ساحة القصر في بطرسبورگ

ساحة القصر في بطرسبورگ هي قلب العاصمة الشمالية لروسيا الاتحادية والمكان المحبب لسكان المدينة وضيوفها والسياح المحليين والاجانب. تعتبر الساحة والمباني المطلة عليها من اروع المجمعات المعمارية في العالم وسميت بساحة القصر لوقوعها امام القصر الشتوي. الساحة مدرجة ضمن قائمة التراث العالمي لمنظمة اليونسكو. انشئت الساحة بأمر من الامبراطور نيقولاي الاول لتخليد انتصار القوات الروسية على جيوش نابليون في الحرب الوطنية عام 1812 . وضع كارل روسي المهندس المعماري المكلف بأنشاء الساحة مخطط المجمع المعماري، الذي تضمن الاستفادة من بعض الابنية القائمة في الموقع وربطها بالمباني الحديثة لتشكل وحدة معمارية متكاملة تخلد النصر الروسي.

شيد في الجانب الجنوبي للساحة مبنى الاركان العامة على شكل نصف دائرة بواجهة يبلغ طولها 580 مترا يتوسطها قوس نصر جميل مزخرف وضعت فوقه عربة المجد تجرها ستة خيول وعليها تماثيل مقاتلين وعربة ثانية تقودها " نيكا " الهة النصر. يبلغ ارتفاع القوس 28 مترا وارتفاع التماثيل 10 امتار وعرض القوس 17 مترا.

في عام 1834 نصب في وسط الساحة عمود الكسندر من حجر الغرانيت على شرف الامبراطور الكسندر الاول. يبلغ وزن العمود اكثر من 600 طن وارتفاعه 47.5 مترمثبت فوقه تمثال ملاك يقتل ثعبانا بالصليب الذي يحمله علامة لانتصار الخير على الشر.

وكان مبنى مقر الحرس اخر المباني التي شيدت على الساحة عام 1843 . اجريت عام 1977 على الساحة ترميمات شاملة ورصفت ارضيتها بديكور جميل. تبقى الساحة المكان الذي يقصده سكان المدينة وضيوفها والسياح، كما ان اكثر المهرجانات الغنائية والاحتفالات الشعبية تقام على الساحة.

- القصر الشتوي – شيد القصر خلال الفترة بين اعوام 1754 – 1762 بتصميم المهندس المعماري بارتولوميو راستريللي الذي وضع عمليا مخطط الساحة. كان القصر مقرا للامبراطور الروسي. حاليا مبنى القصر هو المبنى الرئيسي لمتحف الارميتاج. يعتبر القصر الشتوي اجمل المباني المطلة على الساحة . تبلغ مساحة القصر 9 هكتارات ويتضمن حوالي 1500 غرفة وقاعة. كان القصر حينها اعلى مباني المدينة ولم يكن يسمح باقامة مبنى اخر اعلى منه.

- مبنى الاركان العامة – هذا المبنى ضخم جدا يتوسطه قوس النصر الذي ثبتت فوقه عربة تجرها ستة خيول وعليها تماثيل لمقاتلين وعربة ثانية تقودها " نيكا " الهة النصر. لقد صمم المهندس المعماري هذا المبنى، بحيث استفاد واستخدم المباني التي كانت قائمة منذ النصف الثاني من القرن الـ 18 . كان القسم الغربي من المبنى مخصا للاركان العامة اما القسم الشرقي فخصص لوزارتي الخارجية والمالية وكنيسة ( حاليا جزء من متحف الارميتاج ). المبنى مشيد على الطراز الكلاسيكي . - عمود الكسندر – اقيم هذا العمود في وسط ساحة القصر عام 1834 تخليدا للامبراطور الكسندر الاول الذي في اثناء حكمه انتصرت القوات الروسية على قوات نابليون الغازية. لا مثيل لهذا العمود الغرانيتي في العالم حيث يبلغ طوله مع القاعدة وتمثال الملاك الذي مثبت في قمته 47.5 متر. العمود مثبت على قاعدة من الغرانيت ايضا نقشت عليها انواع الاسلحة التي استخدمت في تلك الحرب وكذلك رموز تخلد النصر الكبير.

- مبنى مقر الحرس – استمر بناء هذا المبنى من عام 1837 ولغاية 1843 . المبنى مشيد على الطراز الكلاسيكي المتأخر. بعد ان انجز بناء مبنى الاركان العامة كان لابد من اكمال بناء الساحة حسب المخطط المقرر. لذا امر الامبراطور بافل الاول بتشييد مبنى في الجانب الشرقي للساحة ليكون مقرا للحرس حيث ان المبنى القديم لم يعد يفي بالغرض. يتكون المبنى من قسمين متعامدين تطل واجهة احدهما على الساحة وتطل واجهة القسم الاخر على كورنيش نهر مويكا.

-الارميتاج – اضخم واشهر متاحف روسيا واحد اكبر متاحف العالم

يقع متحف الارميتاج في مدينة بطرسبورگ، وهو اضخم متاحف روسيا الاتحادية واحد اضخم متاحف العالم. يحتوي المتحف على اكثر من 3 ملايين لوحة فنية وقطع اثرية ومنحوتات لكبار الفنانيين.

كان المتحف في بداية الامر يتمثل في مجموعة لوحات فنية ازداد عددها مع مرور الوقت كانت تبتاعها الامبراطورة يكاتيرينا الثانية وتضعها في احدى قاعات القصر الشتوي المعزولة ( من هنا جاءت تسميته عن الفرنسية – ارميتاج وتعني مكان منعزل ).

بدأت الامبراطورة يكاتيرينا الثانية بجمع اللوحات الفنية عام 1764 بعد شرائها 220 لوحة فنية لرسامين من هولندا وبلجيكا من احد التجار في برلين ووضعتهم في قاعات القصر الشتوي المنعزلة. تبع ذلك عام 1769 شراء اكثر من 600 لوحة فنية من مدينة درسدن الالمانية. تبع ذلك عام 1772 شراء مجموعة لوحات البارون كروزا في باريس. كانت هذه المجموعة تضم اعمالا لرسامين من ايطاليا وفرنسا وهولندا وبلجيكا، كان من بين هذه اللوحات، لوحة " العائلة المقدسة " للرسام روفائيل ولوحات لرامبرانت وغيرهم. وفي عام 1779 اقتنيت مجموعة لوحات تعود لرئيس الوزراء البريطاني ومجموعة اخرى يزيد عددها عن 5000 لوحة من بروكسل. بعد ذلك اشترت الامبراطورة يكاتيرينا الثانية مجموعة تعود لمصرفي بريطاني كان بينها تمثال " ولد يجلس القرفصاء " لميكائل انجلو وتماثيل قديمة تعود الى العهد اليوناني وغيرها اضافة لذلك كانت الامبراطورة تقتني لوحات فنية ومنحوتات من الرسامين الروس والاوروبيين نفذت حسب طلبها. كما انها اشترت مكتبة فولتير وديدرو. عند وفاة الامبراطورة عام 1796 كان مجموع اللوحات التي تملكها 3996 .

استمر شراء اللوحات الفنية في عهد الكسندر الاول ونيقولاي الاول خاصة لوحات بريشة رسامين لم تكن اعمالهم موجودة في الارميتاج. افتتح متحف الارميتاج للجمهور عام 1852 حيث كان في حينها احد اغنى المتاحف في العالم بما يحتويه من تماثيل شرقية ومصرية قديمة ويونانية والعصور الوسطى وفنون اوروبا اضافة الى الاثار القديمة المكتشفة في اسيا والحضارة الروسية بين القرن الـ 8 والقرن الـ 19 . استمر عدد اللوحات الفنية بالازدياد وكان بينها لوحات تعود الى الرسام رامبرانت مثل " عودة الابن الضال " التي رسمها في هولندا في القرن الـ 17 خلال الفترة الفاصلة بين العصور الوسطى والحديثة. بعد قيام ثورة اكتوبر عام 1917 ازدادت معروضات المتحف من اللوحات الفنية والتماثيل بشكل كبير نتيجة تأميم ومصادرة المجموعات الفنية الخاصة.

ونتيجة لاعادة توزيع ممتلكات المتاحف في موسكو وبطرسبورگ استلم الارميتاج لوحات لرسامين روس واوروبيين. في حين نقلت " غرفة الالماس " الى موسكو حيث شكلت اساس متحف الالماس كما نقلت بعض اللوحات الفنية الى متحف الفنون التشكيلية بموسكو.

خلال سنوات الحرب الوطنية العظمى نقلت اغلب معروضات المتحف الى مناطق ماوراء سلسلة جبال الاورال واغلق المتحف امام الجمهور. ألا ان العاملين في المتحف استمروا في نشاطهم العلمي والقاء المحاضرات. في عام 1956 افتتح الطابق الثالث للمتحف.

محتويات المتحف – تعكس محتويات ومعروضات المتحف تطور الفنون في العالم منذ العصر الحجري القديم وحتى نهاية القرن الـ 20 وكذلك الاثار الثقافية المكتشفة على كامل اراضي الاتحاد السوفيتي السابق مثل التماثيل الصغيرة ومنها تمثال " فينوس العصر الحجري " وقطع خزفية وبرونزية وغيرها. وتضم مجموعة اللوحات اعمالا تعود الى رسامين غربيين عظام من القرن الـ 13 لغاية القرن الـ 20 واغلبها يعود الى الرسامين من ايطاليا ( القرن الـ 16 – القرن الـ 18 ) وفرنسا ( القرن الـ 17 وبداية القرن الـ 20 ) واسبانيا ( القرن الـ 16 – القرن الـ 18 ) وهولندا وبلجيكا ( القرن الـ 17 ) وغيرهم.

وزعت معروضات الارميتاج على عدد من المباني التي تشكل المجمع المعماري الرائع المطل على ساحة القصر. تطل جميع المباني على نهر نيفا ويمثل القصر الشتوي المبنى الرئيسي للمتحف. توجد للمتحف فروع في كل من امستردام عاصمة هولندا ومدينة قازان عاصمة جمهورية تتارستان ومدينة فيبورغ في مقاطعة لينينغراد.

ان زائر المتحف يمكن ان يرى نفسه في مصر القديمة او بلاد مابين النهرين وبلاد الاغريق ويتعرف على حياة قبائل سيبيريا ويشاهد المومياء المصرية والخزف الاغريقي وتماثيل يونانية واسقوثية وغيرها، ناهيك عن اللوحات الفنية لرسامين امثال ليوناردو دا فينتشي ورافائيل وتيتسيان والغريكو ورامبرانت وكلود مونيه و كامل بيسارو وبيكاسو وغيرهم وتماثيل من نحت ميكائيل انجلو وغيره. .خطأ استشهاد: وسم <ref> غير صحيح؛ أسماء غير صحيحة، على سبيل المثال كثيرة جدا

الكاتدرائيات والمعابد

While many cathedrals and buildings formerly owned by churches and monasteries still belong to the Russian government, since their seizure in 1917, some were eventually returned to congregations. The largest cathedral in the city is St Isaac's Cathedral

المتاحف والمناطق الشهيرة

الصروح والتماثيل

حدائق الضواحي والقصور

المجتمع والثقافة

الحياة الثقافية والتعليمية. سانت بطرسبرج مركز ثقافي وتعليمي مهم. ففي المدينة أكثر من أربعين مؤسسة تعليمية، وتعتبر جامعتها من أكبر الجامعات الروسية. وفيها معهد الموسيقى الذي تأسس عام 1862م وتخرج فيه العديد من مشاهير الموسيقيين. ويضم متحف الهرميتاج مجموعة طيبة من التماثيل الإغريقية والرومانية وفن الباروك ومن الفن الإسلامي وفن عصر النهضة، كما يضم لوحات عدة للانطباعيين الفرنسيين. ويحتوي المتحف الروسيّ على مجموعة كبيرة من الفنون الروسية.

سانت بطرسبرج مدينة صناعية قديمة وكانت تنتج نحو 3% من الإنتاح الصناعي للاتحاد السوفييتي (سابقًا). والمدينة رائدة في صناعة السفن التي بدأت فيها في مطلع القرن الثامن عشر الميلادي. وأهم الصناعات الحديثة بها هي صناعة الآلات والصناعات الكيميائية والمعدَّات الكهربائية وصناعة النسيج. والمدينة مركز تجاري، وبها مرفأ ممتاز ويخدمها 12 خطًا من خطوط السكك الحديدية. وفي المدينة شبكة ممتازة من المواصلات العامة.

الموسيقى في سانت بطرسبرگ

سانت بطرسبرگ في الأفلام

سانت بطرسبرگ في الأدب

الرياضة

التعليم

اعتبارا من 2006[تحديث]–2007, there were 1,024 kindergartens, 716 public schools and 80 vocational schools in Saint Petersburg.[81] The largest of the public higher education institutions is Saint Petersburg State University, enrolling approximately 32,000 undergraduate students; and the largest non-governmental higher education institutions is the Institute of International Economic Relations, Economics, and Law. Other famous universities are Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University, Herzen University, Saint Petersburg State University of Economics and Finance and Saint Petersburg Military engineering-technical university. However, the public universities are all federal property and do not belong to the city.

تكريم

A minor planet 2046 Leningrad discovered in 1968 by Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova is named after the city, when its name was Leningrad.[82]

المدن الشقيقة

هذه قائمة بالمدن التي لها علاقة مدن شقيقة مع سانت پطرسبورگ. [83]

معرض الصور

Peter the Great's Palace, built in 1714-1725 in Peterhof

Menshikov Palace, the seat of the first Governor

Narva Triumphal Gate at the Stachek Square.

The Winter Palace was stormed by Bolshevik communists at night in October 1917

Lenin's mug shot 1895

1911 photo by the Levitsky Company of the last Russian Royal Family. Clockwise from top: the Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna, the Grand Duchess Anastasia, the Tsarevich Alexei, the Grand Duchess Tatiana, Tsar Nicholas II, the Grand Duchess Olga, and the Grand Duchess Maria

The cruiser Aurora, رمز ثورة اكتوبر, حالياً متحف

The monument to Sergey Kirov on Kirov Square of Saint Petersburg

Bombings of the Nevsky prospekt. Nazi bombings killed thousands of civilians in Leningrad

Hotel Pribaltiyskaya

Hotel Astoria in winter

View of Hermitage Museum complex, St. Petersburg, روسيا, from across the Neva river. The Winter Palace is to the right.

Liteyny Bridge at night

The Trinity Bridge

Kunstkamera, Palace Bridge, a rostral column and the spire of Peter and Paul Cathedral

Peter's Summer Palace in the Summer Garden

Façade of the Larger Marble Palace. For a night view see here.

The church of Sts. Simon and Anna, the patrons saints of Empress Anna (1734, designed by Mikhail Zemtsov)

Saint Petersburg Mosque (opened in 1913)

Palace Square with the Alexander Column, view from the Winter Palace

Spire of the Russian Admiralty

Arch of the New Holland Island

The State Russian Museum, former Mikhailovsky Palace

Former Singer's House (now a popular bookstore "House of Books")

A horse tamer on the Anichkov Bridge by Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg

Samson and the Lion fountain in Peterhof

The building of the Mining Academy (1811) is a Neoclassical masterpiece by Andrey Voronikhin.

The Twelve Collegia building of St. Petersburg State University

هامش

- ^ Shevchenko, Elizaveta (11 October 2021). "The Five Names of St. Petersburg". news.itmo.ru (in الروسية). Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Sobchak, Anatoly. Город четырех революций – Дух преобразования... (in الروسية). Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "18th Century in the Russian history". Rusmania. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ McColl, R.W., ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of world geography. Vol. 1. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 633–634. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (2020). The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won (in الإنجليزية) (Reprint ed.). New York: Basic Books. pp. 3, 308. ISBN 978-1541674103.

- ^ أ ب Nelsson, Richard (1 September 2021). "Leningrad becomes St Petersburg – archive, 1991". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 13 July 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ V. Morozov. The Discourses of Saint Petersburg and the Shaping of a Wider Europe, Copenhagen Peace Research Institute, 2002. ISSN 1397-0895

- ^ "Saint Petersburg Tourism – A Look At The Growth of Tourism in Russia's Northern Capital". St Petersburg Essential Guide. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Fes, Nick (4 February 2019). "Saint Petersburg: Number Of Tourists Increased As Well As The Black Market". TourismReview. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Leningrad, Petersburg and the Great Name Debate". The New York Times. 13 June 1991. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Masters, Tom; Richmond, Simon (2015). Lonely Planet St Petersburg. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1743605035. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ أ ب E. M. Pospelow (1993). Имена городов: вчера и сегодня (1917—1992): Топонимический словарь [City names: yesterday and today (1917–1992): Toponymic dictionary]. Moscow: Русские словари. p. 128.

- ^ Bonavia, Michael (1990). London Before I Forget. The Self-Publishing Association Ltd. p. 72. ISBN 1-85421-082-3.

- ^ أ ب Nesterov, V. Знаешь ли ты свой город ("Do you know your city?"). Leningrad, 1958, p. 58.

- ^ أ ب "Петроград – Энциклопедия "Вокруг света"". Vokrugsveta.ru. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ "31 August 1914 St.Petersburg renamed to Petrograd" (in الروسية). Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ Orttung, Robert W. (1995). "Chronology of Major Events". From Leningrad to Saint Petersburg. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 273–277. ISBN 978-0-312-12080-1. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Some non-official names of Saint Petersburg". ruslinguaschool.com. 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Russia won't close Tsar Peter's 'window to Europe', Kremlin says". Reuters. 2 June 2022. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

Peter, who ruled from 1682 to 1725, oversaw Russia's transformation into a major European power and founded the city of Saint Petersburg, dubbed Russia's "window to Europe".

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (24 May 2003). "Window on the west". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "St. Petersburg". European Council. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ "Reise nach St. Petersburg – 6 Tage | Gruppen- und maßgeschneiderte Touren | Pauschalreisen nach Russland". Russlanderleben.de. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ "Winter in St. Petersburg". Autentic-distribution.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Doka, Konstantin Afanasʹevich (1997). Saint Petersburg : the city of the white nights. Doka, Natalʹi︠a︡ Aleksandrovna., Vesnin, Sergeĭ., Williams, Paul. St. Petersburg: P-2 Art Publishers. ISBN 5890910310. OCLC 644640534.

- ^ "The City of White Nights – Saint Petersburg". Designcollector. 31 July 2018. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Olivia, Griese (January 2005). ""Palmyra des Nordens": St. Petersburg – eine nordosteuropäische Metropole?". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. Franz Steiner Verlag. 53 (3): 349–362. JSTOR 41051447.

- ^ Rex A. Wade The Russian Revolution, 1917 2005 Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-84155-0[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ "The common characteristic of Saint Petersburg". russia-travel.ws. 2005–2008. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Kann, Pavel Yakovlevich (1963). Leningrad: A Short Guide. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. pp. 132–133. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ "Ленинградская область в целом: Административно-территориальное деление Ленинградской области". Lenobltrans.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "Как советская власть уничтожала наследие русской истории". ВЗГЛЯД.РУ. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Ленинские, сталинские и хрущевские гонения на Церковь. Церковный ответ на гонения – читать, скачать". azbyka.ru (in الروسية). Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ "Жизнь без веры: утраченные церкви Петербурга". РИА Новости (in الروسية). 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Stalin's Terror: High Politics and Mass Repression in the Soviet Union, Barry McLoughlin and Kevin McDermott (eds). Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, p. 6

- ^ "The Russian historian giving Stalin's victims back their identity". France 24. 29 January 2018. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ Nezhikhovsky, R.A. Река Нева и Невская губа [The Neva River and Neva Bay], Leningrad: Gidrometeoizdat, 1981.

- ^ أ ب "Pogoda.ru.net" (in Russian).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Climate St. Peterburg – Historical weather records". Tutiempo.net. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Архив погоды в Санкт-Петербурге, Санкт-Петербург". Rp5.ru. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة2021Census - ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1". Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года (2010 All-Russia Population Census) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Demoscope Weekly (1989). "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров". Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года[All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. Retrieved August 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Information on the number of registered births, deaths, marriages and divorces for January to December 2022". ROSSTAT. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ "Birth rate, mortality rate, natural increase, marriage rate, divorce rate for January to December 2022". ROSSTAT. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ^ Суммарный коэффициент рождаемости [Total fertility rate]. Russian Federal State Statistics Service (in الروسية). Archived from the original (XLSX) on 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ "Демографический ежегодник России" [The Demographic Yearbook of Russia] (in الروسية). Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat). Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Национальный состав и владение языками, гражданство". perepis2002.ru. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Martin, Terry (1998). "The Origins of Soviet Ethnic Cleansing" (PDF). The Journal of Modern History. 70 (4): 813–861. doi:10.1086/235168. ISSN 1537-5358. JSTOR 10.1086/235168. S2CID 32917643. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Chistyakova, N. Третье сокращение численности населения... и последнее? Archived 28 يوليو 2011 at the Wayback Machine Demoscope Weekly 163–164, 1–15 August 2004.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Saint Petersburg" Chistyakov, A. Yu. Население (обзорная статья) Archived 4 أكتوبر 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Энциклопедия Санкт-Петербурга

- ^ "В первом полугодии продолжалось умеренное повышение числа рождений". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ أ ب "Естественное движение населения в разрезе субъектов Российской Федерации". Gks.ru. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ Russian statistics Основные показатели социально-демографической ситуации в Санкт-Петербурге

- ^ "Пандемия COVID-19 привела к падению рождаемости в Петербурге". M.dp.ru. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Виталий Трофимов-Трофимов (30 September 2013). "Религиозное лицо Петербурга". ok-inform.ru. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia" Archived 6 ديسمبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Sreda, 2012.

- ^ 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2017. Archived.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Russian federation". Constitution.ru. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "Russian source: Charter of Saint Petersburg City". Gov.spb.ru. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "Федеральный закон от 02.05.2012 N 40-ФЗ "О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон "Об общих принципах организации законодательных (представительных) и исполнительных органов государственной власти субъектов Российской Федерации" и Федеральный закон "Об основных гарантиях избирательных прав и права на участие в референдуме граждан Российской Федерации"". garant.ru. Archived from the original on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "Закон Санкт-Петербурга от 26.06.2012 N 339-59". ppt.ru. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ Александр Беглов назначен врио Губернатора Санкт-Петербурга (in الروسية). Rambler news. 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Official website of the Northwestern Federal District (Russian)". Szfo.ru. 25 June 2009. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "О территориальном устройстве Санкт-Петербурга". gov.spb.ru. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ G.N. Georgano Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886–1930. (London: Grange-Universal, 1985)

- ^ "Cruise St Petersburg, Discover the Baltic". 30 December 2008. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ "ЗАО "Терра-Нова" | Крупнейший в Европе проект по образованию и комплексному развитию территории в западной части Васильевского острова Санкт-Петербурга". Mfspb.ru. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Budget of Saint Petersburg (Russian document)". City of Saint Petersburg. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- ^ "Валовой региональный продукт по субъектам Российской Федерации в 1998–2016гг. (в текущих основных ценах; млн.рублей)". Gks.ru. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "Валовой региональный продукт на душу населения (в текущих основных ценах; рублей)". Gks.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ "Отраслевая структура ВРП по видам экономической деятельности (по ОКВЭД) за 2005 год". Gks.ru. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ^ Data of the Government of Saint Petersburg

- ^ "Passport of St. Petersburg Industrial Zones" (PDF). regionen-russland.de. 2015. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2017.

- ^ "ОТЧЕТ за 2006/2007 учебный год". Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. p. 166. ISBN 3540002383.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Sister_Cities_to_Saint_Petersburg

- ^ "Venice suspends sister city with St Petersburg over gay bill". ansa.com. 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2013-01-30.

المصادر

- Нежиховский Р. А. Река Нева и Невская губа, Leningrad, Гидрометеоиздат, 1981.

- Oleg Kobtzeff, "Espaces et cultures du Bassin de la Neva: représentations mythiques et réalités géopolitiques", in-Saint-Petersbourg: 1703-2003, Actes du Colloque international, Université de Nantes, Mai 2003, ouvrage coordonné par Walter Zidaric, CRINI, Nantes, 2004. ISBN 2-9521752-0-9

- Dmitri Volkogonov Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy, 1996, ISBN-10: 0761507183

- Edvard Radzinsky Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives, 1997, ISBN-10: 0385479549

- Stalin and the Betrayal of Leningrad by John Barber: [2]

- Acton, Edward, Vladimir Cherniaev, and William G. Rosenberg, eds. A Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921 (Bloomington, 1997)

- Edward Acton Rethinking the Russian Revolution 1990 Oxford University Press ISBN 0713165308

- Voline The Unknown Revolution Black Rose Books

- Pipes, Richard. The Russian Revolution (New York, 1990)

- Figes, Orlando. A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924, : ISBN 0-14-024364

- Reed, John. Ten Days that Shook the World. 1919, 1st Edition, published by BONI & Liveright, Inc. for International Publishers. Transcribed and marked by David Walters for John Reed Internet Archive. Penguin Books; 1st edition. June 1, 1980. ISBN 0-14-018293-4.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

قراءات اضافية

- Amery, Colin, Brian Curran & Yuri Molodkovets. St. Petersburg. London: Frances Lincoln, 2006. ISBN 0711224927.

- Bater, James H. St. Petersburg: Industrialization and Change. Montreal: McGuill-Queen’s University Press, 1976. ISBN 0773502661.

- Berelowitch, Wladimir & Olga Medvedkova. Histoire de Saint-Pétersbourg. Paris: Fayard, 1996. ISBN 2213596018.

- Buckler, Julie. Mapping St. Petersburg: Imperial Text and Cityshape. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005 ISBN0691113491.

- Clark, Katerina, Petersburg, Crucible of Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- George, Arthur L. & Elena George. St. Petersburg: Russia's Window to the Future, The First Three Centuries. Lanham: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1589790170.

- Glantz, David M. The Battle for Leningrad, 1941-1944. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002. ISBN 0700612084.

- Hellberg-Hirn, Elena. Imperial Imprints: Post-Soviet St. Petersburg. Helsinki: SKS Finnish Literature Society, 2003. ISBN 9517464916.

- Knopf Guide: St. Petersburg. New York: Knopf, 1995. ISBN 0679762027.

- Eyewitness Guide: St. Petersburg.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. Sunlight at Midnight: St. Petersburg and the Rise of Modern Russia. New York: Basic Books, 2000. ISBN 0465083234.

- Lubbeck, William; Hurt, David B. At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North. Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-932033-55-6).

- Orttung, Robert W. From Leningrad to St. Petersburg: Democratization in a Russian City. New York: St. Martin’s, 1995. ISBN 0312175612.

- Ruble, Blair A. Leningrad: Shaping a Soviet City. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 0877723478.

- Shvidkovsky, Dmitry O. & Alexander Orloff. St. Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars. New York: Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 0789202174.

- Volkov, Solomon. St. Petersburg: A Cultural History. New York: Free Press, 1995. ISBN 0028740521.

- St. Petersburg:Architecture of the Tsars. 360 pages. Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN-10: 0789202174

- Saint Petersburg: Museums, Palaces, and Historic Collections: A Guide to the Lesser Known Treasures of St. Petersburg. 2003. ISBN 1593730004

وصلات خارجية

- WikiSatellite view of Saint Petersburg at WikiMapia

- Official website of St. Petersburg City Administration

- 463 casual photos of St. Petersburg from 5 july 2007 walk from Rentgena street to Repina square

- Key Tourist Sights on Google Map linked to Official websites and/or wiki pages.

- Map of Saint Petersburg (بالروسية)

- Historical maps (بالروسية)

- PetersburgCity.com

- Many pages about St.Petersburg's architecture and history with hundreds of images

- Photo-site about life in Saint-Petersburg.

- Saint Petersburg in 1900 - a photographic travelogue

- Encyclopaedia of Saint Petersburg

- St. Petersburg in Architecture, from University of Michigan

- Vintage postcards of St. Petersburg

- History and photos of the St. Petersburg bridges

- Weather of Saint Petersburg, 6 days (بالروسية)

- World Photos. St.Petersburg

- Sights of Saint-Petersburg - information and photos

- سانت بطرسبرغ تقع عند الإحداثيات

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from November 2019

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 uses الروسية-language script (ru)

- CS1 errors: extra text: pages

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2023

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Pages using multiple image with manual scaled images

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2021

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة للتحديث من يناير 2011

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2016

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2006

- سانت پطرسبورگ

- مدن اتحادية في روسيا

- مواقع التراث العالمي في روسيا

- مدن بطلة في الاتحاد السوڤيتي

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في 1703

- عواصم وطنية سابقة

- موانئ بحر البلطيق

- موانئ روسيا

- عواصم مخططة

- أسطول البلطيق