فينكس، أريزونا

Phoenix | |

|---|---|

الكنية:

| |

Interactive map of Phoenix | |

| الإحداثيات: 33°26′54″N 112°04′26″W / 33.44833°N 112.07389°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Maricopa |

| Settled | 1867 |

| Incorporated | February 25, 1881 |

| أسسها | Jack Swilling |

| السمِيْ | Phoenix, mythical creature |

| الحكومة | |

| • النوع | Council–manager |

| • الكيان | Phoenix City Council |

| • Mayor | Kate Gallego (D) |

| المساحة | |

| • State Capital | 519٫28 ميل² (1٬344٫94 كم²) |

| • البر | 518٫27 ميل² (1٬342٫30 كم²) |

| • الماء | 1٫02 ميل² (2٫63 كم²) |

| المنسوب | 1٬086 ft (331 m) |

| التعداد | |

| • State Capital | 1٬608٬139 |

| • Estimate (2021)[3] | 1٬624٬569 |

| • الترتيب | 11th in North America 5th in the United States 1st in Arizona |

| • الكثافة | 3٬102٫92/sq mi (1٬198٫04/km2) |

| • Urban | 3٬976٬313 (US: 11th) |

| • الكثافة الحضرية | 3٬580٫7/sq mi (1٬382٫5/km2) |

| • العمرانية | 4٬845٬832 (US: 10th) |

| صفة المواطن | Phoenician |

| GDP | |

| • Phoenix (MSA) | $362.1 billion (2022) |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC–07:00 (MST (no DST)) |

| ZIP Codes | 85001–85024, 85026-85046, 85048, 85050-85051, 85053-85054, 85060-85076, 85078-85080, 85082-85083, 85085-85087 |

| Area codes | |

| FIPS code | 04-55000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 44784 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

فينكس (إنگليزية: Phoenix ؛ /ˈfiːnᵻks/ FEE-niks; قالب:Lang-nv, قالب:IPA-nv; O'odham: S-ki:kigk;[7] إسپانية: Fénix;[8] قالب:Lang-yuf-x-wal[9])، هي مدينة تقع في مقاطعة ماريكوبا ، أريزونا، الولايات المتحدة. وهي عاصمة وأكبر مدن ولاية أريزونا الواقعة في جنوب غرب الولايات المتحدة، وحاضرة مقاطعة ماريكوبا. تأسست كمدينة في 25 فبراير 1881، وقد كانت تعرف باسم هوزدو والتي تعني "المنطقة الحارة" بلغة نافاجو. وتلقب الآن بـ "وادي الشمس".

فينكس هي |خامس أكبر مدن الولايات المتحدة من حيث عدد السكان، وأكبر عواصم الولايات تعداداً في الولايات المتحدة.[10] فقد بلغ عدد سكانها 1,608,139 نسمة في عام 2020.[11]

Phoenix is the most populous city of the Phoenix metropolitan area, also known as the Valley of the Sun, which in turn is part of the Salt River Valley and Arizona Sun Corridor. The metro area is the 10th-largest by population in the United States with approximately 4.85 million people اعتبارا من 2020[تحديث], making it the most populous in the Southwestern United States.[12][13] Phoenix, the seat of Maricopa County, is the largest city by area in Arizona, with an area of 517.9 square miles (1,341 km2), and is also the 11th-largest city by area in the United States.[14]

Phoenix was settled in 1867 as an agricultural community near the confluence of the Salt and Gila Rivers and was incorporated as a city in 1881. It became the capital of Arizona Territory in 1889.[15] Its canal system led to a thriving farming community with the original settlers' crops, such as alfalfa, cotton, citrus, and hay, remaining important parts of the Economy of Phoenix for decades.[16][17] Cotton, cattle, citrus, climate, and copper were known locally as the "Five C's" anchoring Phoenix's economy. These remained the driving forces of the city until after World War II, when high-tech companies began to move into the valley and air conditioning made Phoenix's hot summers more bearable.[18]

Phoenix is the cultural center of Arizona.[19] It is in the northeastern reaches of the Sonoran Desert and is known for its hot desert climate.[20][21] The region's gross domestic product reached over $362 billion by 2022.[22] The city averaged a four percent annual population growth rate over a 40-year period from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s,[23] and was among the nation's ten most populous cities by 1980. Phoenix is also one of the largest majority-Hispanic cities in the United States, with 42% of its population being Hispanic.[24]

مساحتها 1230.5 كم2 (475.1 ميل مربع)، وهي ثالث أكبر عاصمة أمريكية من حيث المساحة بعد كل من جونو (آلاسكا) وأوكلاهوما سيتي (أوكلاهوما).

فينيكس واحدة من أسرع المدن نموًا في الولايات المتحدة، تشمل منتجاتها المصنّعة الرئيسية: أجهزة الحاسوب والمعدات الإلكترونية والكيميائيات والأسمدة والأسلحة العسكرية والأطعمة المحفوظة، وتدر السياحة على فينيكس نحو 1,8 بليون دولار أمريكي سنويًا.

التاريخ

Early history

The Hohokam people occupied the Phoenix area for 2,000 years.[25][26] They created roughly 135 miles (217 kilometers) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable, and paths of these canals were used for the Arizona Canal, Central Arizona Project Canal, and the Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct. They also carried out extensive trade with the nearby Ancient Puebloans, Mogollon, and Sinagua, as well as with the more distant Mesoamerican civilizations.[27] It is believed periods of drought and severe floods between 1300 and 1450 led to the Hohokam civilization's abandonment of the area.[28]

After the departure of the Hohokam, groups of Akimel O'odham (commonly known as Pima), Tohono O'odham, and Maricopa tribes began to use the area, as well as segments of the Yavapai and Apache.[29] The O'odham were offshoots of the Sobaipuri tribe, who in turn were thought to be the descendants of the Hohokam.[30][31][32]

The Akimel O'odham were the major group in the area. They lived in small villages with well-defined irrigation systems that spread over the Gila River Valley, from Florence in the east to the Estrellas in the west. Their crops included corn, beans, and squash for food as well as cotton and tobacco. They banded with the Maricopa for protection against incursions by the Yuma and Apache tribes.[33] The Maricopa are part of the larger Yuma people; however, they migrated east from the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers in the early 1800s, when they began to be enemies with other Yuma tribes, settling among the existing communities of the Akimel O'odham.[34][35][29]

The Tohono O'odham also lived in the region, but largely to the south and all the way to the Mexican border.[36] The O'odham lived in small settlements as seasonal farmers who took advantage of the rains, rather than the large-scale irrigation of the Akimel. They grew crops such as sweet corn, tapery beans, squash, lentils, sugar cane, and melons, as well as taking advantage of native plants such as saguaro fruits, cholla buds, mesquite tree beans, and mesquite candy (sap from the mesquite tree). They also hunted local game such as deer, rabbit, and javelina for meat.[37][38]

The Mexican–American War ended in 1848, Mexico ceded its northern zone to the United States, and the region's residents became U.S. citizens. The Phoenix area became part of the New Mexico Territory.[39] In 1863, the mining town of Wickenburg was the first to be established in Maricopa County, to the northwest of Phoenix. Maricopa County had not been incorporated; the land was within Yavapai County, which included the major town of Prescott to the north of Wickenburg.

The Army created Fort McDowell on the Verde River in 1865 to forestall Indian uprisings.[40] The fort established a camp on the south side of the Salt River by 1866, which was the first settlement in the valley after the decline of the Hohokam. Other nearby settlements later merged to become the city of Tempe.[41]

Founding and incorporation

The history of Phoenix begins with Jack Swilling, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War who prospected in the nearby mining town of Wickenburg in the newly formed Arizona Territory. As he traveled through the Salt River Valley in 1867, he saw a potential for farming to supply Wickenburg with food. He also noted the eroded mounds of dirt that indicated previous canals dug by native peoples who had long since left the area. He formed the Swilling Irrigation and Canal Company that year, dug a large canal that drew in river water, and erected several crop fields in a location that is now within the eastern portion of central Phoenix near its airport. Other settlers soon began to arrive, appreciating the area's fertile soil and lack of frost, and the farmhouse Swilling constructed became a frequently-visited location in the valley.[42][43] Lord Darrell Duppa was one of the original settlers in Swilling's party, and he suggested the name "Phoenix", as it described a city born from the ruins of a former civilization.[25]

The Board of Supervisors in Yavapai County officially recognized the new town on May 4, 1868, and the first post office was established the following month with Swilling as the postmaster.[25] In October 1870, valley residents met to select a new townsite for the valley's growing population. A new location three miles to the west of the original settlement, containing several allotments of farmland, was chosen, and lots began to officially be sold under the name of Phoenix in December of that year. This established the downtown core in a grid layout pattern that has been the hallmark of Phoenix's urban development ever since.

On February 12, 1871, the territorial legislature created Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County; it was the sixth one formed in the Arizona Territory. The first election for county office was held in 1871 when Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff. He ran unopposed when the other two candidates (John A. Chenowth and Jim Favorite) fought a duel; Chenowth killed Favorite and was forced to withdraw from the race.[25]

The town grew during the 1870s, and President Ulysses S. Grant issued a land patent for the site of Phoenix on April 10, 1874. By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, 16 saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government needed an overhaul. An election was held in 1875, and three village trustees and other officials were elected.[25] By 1880, the town's population stood at 2,453.[44]

By 1881, Phoenix's continued growth made the board of trustees obsolete. The Territorial Legislature passed the Phoenix Charter Bill, incorporating Phoenix and providing a mayor-council government; Governor John C. Fremont signed the bill on February 25, 1881, officially incorporating Phoenix as a city with a population of around 2,500.[25]

The railroad's arrival in the valley in the 1880s was the first of several events that made Phoenix a trade center whose products reached eastern and western markets. In response, the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce was organized on November 4, 1888.[45] The city offices moved into the new City Hall at Washington and Central in 1888.[25] The territorial capital moved from Prescott to Phoenix in 1889, and the territorial offices were also in City Hall.[46] The arrival of the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway in 1895 connected Phoenix to Prescott, Flagstaff, and other communities in the northern part of the territory. The increased access to commerce expedited the city's economic rise. The Phoenix Union High School was established in 1895 with an enrollment of 90.[25]

1900 to World War II

On February 25, 1901, Governor Oakes Murphy dedicated the permanent Capitol building,[25] and the Carnegie Free Library opened seven years later, on February 18, 1908, dedicated by Benjamin Fowler.[47] The National Reclamation Act was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902, which allowed dams to be built on waterways in the west for reclamation purposes.[48] The first dam constructed under the act, Salt River Dam#1, began in 1903. It supplied both water and electricity, becoming the first multi-purpose dam, and Roosevelt attended the official dedication on May 18, 1911. At the time, it was the largest masonry dam in the world, forming a lake in the mountains east of Phoenix.[49] The dam would be renamed after Teddy Roosevelt in 1917,[50] and the lake would follow suit in 1959.[51]

On February 14, 1912, Phoenix became a state capital, as Arizona was admitted to the Union as the 48th state under President William Howard Taft.[52] This occurred just six months after Taft had vetoed a joint congressional resolution granting statehood to Arizona, due to his disapproval of the state constitution's position on the recall of judges.[53] In 1913, Phoenix's move from a mayor-council system to council-manager made it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate; eight years later, its population reached 29,053. In 1920, Phoenix would see its first skyscraper, the Heard Building.[25] In 1929, Sky Harbor was officially opened, at the time owned by Scenic Airways. The city purchased it in 1935 and continues to operate it today.[54]

On March 4, 1930, former U.S. President Calvin Coolidge dedicated a dam on the Gila River named in his honor. However, the state had just been through a long drought, and the reservoir which was supposed to be behind the dam was virtually dry. The humorist Will Rogers, who was on hand as a guest speaker joked, "If that was my lake, I'd mow it."[55] Phoenix's population had nearly doubled during the 1920s and by 1930 stood at 48,118.[25] It was also during the 1930s that Phoenix and its surrounding area began to be called "The Valley of the Sun", which was an advertising slogan invented to boost tourism.[56]

During World War II, Phoenix's economy shifted to that of a distribution center, transforming into an "embryonic industrial city" with the mass production of military supplies.[25] There were three air force fields in the area: Luke Field, Williams Field, and Falcon Field, as well as two large pilot training camps, Thunderbird Field No. 1 in Glendale and Thunderbird Field No. 2 in Scottsdale.[25][57][58]

Post-World War II explosive growth

A town that had just over 65,000 residents in 1940 became America's fifth largest city by 2020, with a population of nearly 1.6 million, and millions more in nearby suburbs. After the war, many of the men who had undergone their training in Arizona returned with their new families. Learning of this large untapped labor pool enticed many large industries to move their operations to the area.[25] In 1948, high-tech industry, which would become a staple of the state's economy, arrived in Phoenix when Motorola chose Phoenix as the site of its new research and development center for military electronics. Seeing the same advantages as Motorola, other high-tech companies, such as Intel and McDonnell Douglas, moved into the valley and opened manufacturing operations.[59][60]

By 1950, over 105,000 people resided in the city and thousands more in surrounding communities.[25] The 1950s growth was spurred on by advances in air conditioning, which allowed homes and businesses to offset the extreme heat experienced in Phoenix and the surrounding areas during its long summers. There was more new construction in Phoenix in 1959 alone than from 1914 to 1946.[61]

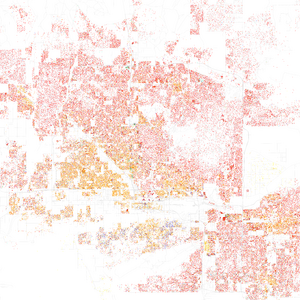

Like many emerging American cities at the time, Phoenix's spectacular growth did not occur evenly. It largely took place on the city's north side, a region that was nearly all Caucasian. In 1962, one local activist testified at a US Commission on Civil Rights of hearing that of 31,000 homes that had recently sprung up in this neighborhood, not a single one had been sold to an African-American.[62] Phoenix's African-American and Mexican-American communities remained largely sequestered on the south side of town. The color lines were so rigid that no one north of Van Buren Street would rent to the African-American baseball star Willie Mays, in town for spring training in the 1960s.[63] In 1964, a reporter from The New Republic wrote of segregation in these terms: "Apartheid is complete. The two cities look at each other across a golf course."[64]

1960s to present

The continued rapid population growth led more businesses to the valley to take advantage of the labor pool,[65] and manufacturing, particularly in the electronics sector, continued to grow.[66] The convention and tourism industries saw rapid expansion during the 1960s, with tourism becoming the third largest industry by the end of the decade.[67] In 1965, the Phoenix Corporate Center opened; at the time it was the tallest building in Arizona, topping off at 341 feet.[68] The 1960s saw many other buildings constructed as the city expanded rapidly, including the Rosenzweig Center (1964), today called Phoenix City Square,[69] the landmark Phoenix Financial Center (1964),[70] as well as many of Phoenix's residential high-rises. In 1965 the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum opened at the Arizona State Fairgrounds, west of downtown. When Phoenix was awarded an NBA franchise in 1968, which would be called the Phoenix Suns,[71][72] they played their home games at the Coliseum until 1992, after which they moved to America West Arena.[73] In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson approved the Central Arizona Project, assuring future water supplies for Phoenix, Tucson, and the agricultural corridor between them.[74][75] The following year, Pope Paul VI created the Diocese of Phoenix on December 2, by splitting the Archdiocese of Tucson, with Edward A. McCarthy as the first Bishop.[76]

In the 1970s the downtown area experienced a resurgence, with a level of construction activity not seen again until the urban real estate boom of the 2000s. By the end of the decade, Phoenix adopted the Phoenix Concept 2000 plan which split the city into urban villages, each with its own village core where greater height and density was permitted, further shaping the free-market development culture. The nine original villages[77] have expanded to 15 over the years (see Cityscape below). This officially turned Phoenix into a city of many nodes, which would later be connected by freeways. The Phoenix Symphony Hall opened in 1972;[78] other major structures which saw construction downtown during this decade were the First National Bank Plaza, the Valley Center (the tallest building in Arizona),[79] and the Arizona Bank building.

On September 25, 1981, Phoenix resident Sandra Day O'Connor broke the gender barrier on the U.S. Supreme Court, when she was sworn in as the first female justice.[80] In 1985, the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, the nation's largest nuclear power plant, began electrical production.[81] Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa both visited the Valley in 1987.[82]

There was an influx of refugees due to low-cost housing in the Sunnyslope area in the 1990s, resulting in 43 different languages being spoken in local schools by 2000.[83] The new 20-story City Hall opened in 1992.[84]

Phoenix has maintained a growth streak in recent years, growing by 24.2% before 2007. This made it the second-fastest-growing metropolitan area in the United States, surpassed only by Las Vegas.[85] In 2008, Squaw Peak, the city's second tallest mountain, was renamed Piestewa Peak after Army Specialist Lori Ann Piestewa, an Arizonan and the first Native American woman to die in combat while serving in the U.S. military, as well as being the first American female casualty of the 2003 Iraq War.[86] 2008 also saw Phoenix as one of the cities hardest hit by the subprime mortgage crisis, and by early 2009 the median home price was $150,000, down from its $262,000 peak in 2007.[87] Crime rates in Phoenix have fallen in recent years, and once troubled, decaying neighborhoods such as South Mountain, Alhambra, and Maryvale have recovered and stabilized. On June 1, 2023, the State of Arizona announced the decision to halt new housing development in the Phoenix metropolitan area that relies solely on groundwater due to a predicted water shortfall.[88]

الجغرافيا

Phoenix is in the south-central portion of Arizona; about halfway between Tucson to the southeast and Flagstaff to the north, in the southwestern United States. By car, the city is approximately 150 miles (240 kilometers) north of the US–Mexico border at Sonoyta and 180 mi (290 km) north of the border at Nogales. The metropolitan area is known as the "Valley of the Sun" due to its location in the Salt River Valley.[56] It lies at a mean elevation of 1,086 feet (331 m), in the northern reaches of the Sonoran Desert.[89]

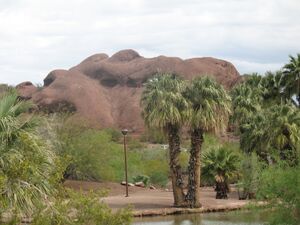

Other than the mountains in and around the city, Phoenix's topography is generally flat, which allows the city's main streets to run on a precise grid with wide, open-spaced roadways. Scattered, low mountain ranges surround the valley: McDowell Mountains to the northeast, the White Tank Mountains to the west, the Superstition Mountains far to the east, and both South Mountain and the Sierra Estrella to the south/southwest. Camelback Mountain, North Mountain, Sunnyslope Mountain, and Piestewa Peak are within the heart of the valley. The city's outskirts have large fields of irrigated cropland and Native American reservation lands.[90] The Salt River runs westward through Phoenix, but the riverbed is often dry or contains little water due to large irrigation diversions. South Mountain separates the community of Ahwatukee from the rest of the city.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 517.9 sq mi (1,341 km2), of which 516.7 sq mi (1,338 km2) is land and 1.2 sq mi (3.1 km2), or 0.2%, is water.

Maricopa County grew by 711% from 186,000 in 1940 to 1,509,000 by 1980, due in part to air conditioning, cheap housing, and an influx of retirees. The once "modest urban sprawl" now "grew by 'epic' proportions—not only a myriad of residential tract developments on both farmland and desert." Retail outlets and office complexes spread out and did not concentrate in the small downtown area. There was low population density and a lack of widespread and significant high-rise development.[91] As a consequence Phoenix became a textbook case of urban sprawl for geographers.[92][93][94][95][96][97] Even though it is the fifth most populated city in the United States, the large area gives it a low density rate of approximately 2,797 people per square mile.[98] In comparison, Philadelphia, the sixth most populous city with nearly the same population as Phoenix, has a density of over 11,000.[99]

Like most of Arizona, Phoenix does not observe daylight saving time. In 1973, Governor Jack Williams argued to the U.S. Congress that energy use would increase in the evening should Arizona observe DST. He went on to say energy use would also rise early in the day "because there would be more lights on in the early morning." Additionally, he said daylight saving time would cause children to go to school in the dark.[100]

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

Since 1979, the city of Phoenix has been divided into urban villages, many of which are based upon historically significant neighborhoods and communities that have since been annexed into Phoenix.[101] Each village has a planning committee appointed directly by the city council. According to the city-issued village planning handbook, the purpose of the village planning committees is to "work with the city's planning commission to ensure a balance of housing and employment in each village, concentrate development at identified village cores, and to promote the unique character and identity of the villages."[102] There are 15 urban villages: Ahwatukee Foothills, Alhambra, Camelback East, Central City, Deer Valley, Desert View, Encanto, Estrella, Laveen, Maryvale, North Gateway, North Mountain, Paradise Valley, Rio Vista, and South Mountain.

The urban village of Paradise Valley is distinct from the nearby Town of Paradise Valley. Although the urban village is part of Phoenix, the town is independent.

In addition to the above urban villages, Phoenix has a variety of commonly referred-to regions and districts, such as Downtown, Midtown, Uptown,[103] West Phoenix, North Phoenix, South Phoenix, Biltmore Area, Arcadia, and Sunnyslope.

Flora and fauna

While some of the native flora and fauna of the Sonoran Desert can be found within Phoenix city limits, most are found in the suburbs and the undeveloped desert areas that surround the city. Native mammal species include coyote, javelina, bobcat, mountain lion, desert cottontail rabbit, jackrabbit, antelope ground squirrel, mule deer, ringtail, coati, and multiple species of bats, such as the Mexican free-tailed bat and western pipistrelle, that roost in and around the city. There are many species of native birds, including Costa's hummingbird, Anna's hummingbird, Gambel's quail, Gila woodpecker, mourning dove, white-winged dove, the greater roadrunner, the cactus wren, and many species of raptors, including falcons, hawks, owls, vultures (such as the turkey vulture and black vulture), and eagles, including the golden and the bald eagle.[104][105]

The greater Phoenix region is home to the only thriving feral population of rosy-faced lovebirds in the U.S. This bird is a popular birdcage pet, native to southwestern Africa. Feral birds were first observed living outdoors in 1987, probably escaped or released pets, and by 2010 the Greater Phoenix population had grown to about 950 birds. These lovebirds prefer older neighborhoods where they nest under untrimmed, dead palm tree fronds.[106][107]

The area is also home to a plethora of native reptile species including the Western diamondback rattlesnake, Sonoran sidewinder, several other types of rattlesnakes, Sonoran coral snake, dozens of species of non-venomous snakes (including the Sonoran gopher snake and the California kingsnake), the gila monster, desert spiny lizard, several types of whiptail lizards, the chuckwalla, desert horned lizard, western banded gecko, Sonora mud turtle, and the desert tortoise. Native amphibian species include the Couch's spadefoot toad, Chiricahua leopard frog, and the Sonoran desert toad.[108]

Phoenix and the surrounding areas are also home to a wide variety of native invertebrates including the Arizona bark scorpion, giant desert hairy scorpion, Arizona blond tarantula, Sonoran Desert centipede, tarantula hawk wasp, camel spider, and tailless whip scorpion. Of great concern is the presence of Africanized bees which can be extremely dangerous—even lethal—when provoked.

The Arizona Upland subdivision of the Sonoran Desert (of which Phoenix is a part) has "the most structurally diverse flora in the United States." One of the most well-known types of succulents, the giant saguaro cactus, is found throughout the city and its neighboring environs. Other native species are the organpipe, barrel, fishhook, senita, prickly pear and cholla cacti; ocotillo; Palo Verde trees and foothill and blue paloverde; California fan palm; agaves; soaptree yucca, Spanish bayonet, desert spoon, and red yucca; ironwood; mesquite; and the creosote bush.[109][110]

Many non-native plants also thrive in Phoenix including, but not limited to, the date palm, Mexican fan palm, pineapple palm, Afghan pine, Canary Island pine, Mexican fencepost cactus, cardon cactus, acacia, eucalyptus, aloe, bougainvillea, oleander, lantana, bottlebrush, olive, citrus, and red bird of paradise.

المناخ

| متوسطات الطقس لفينكس،أريزونا | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| شهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة |

| العظمى القياسية °F (°C) | 88 (31) | 92 (33) | 100 (38) | 105 (41) | 114 (46) | 122 (50) | 121 (49) | 116 (47) | 116 (47) | 107 (42) | 96 (36) | 87 (31) | 122 (50) |

| متوسط العظمى °ف (°م) | 67 (19) | 71 (22) | 76 (24) | 85 (29) | 94 (34) | 104 (40) | 107 (42) | 105 (41) | 99 (37) | 88 (31) | 75 (24) | 70 (21) | 87 (31) |

| متوسط الصغرى °ف (°م) | 45 (7) | 48 (9) | 51 (11) | 58 (14) | 67 (19) | 75 (24) | 81 (27) | 80 (27) | 75 (24) | 63 (17) | 50 (10) | 44 (7) | 61 (16) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°C) | 16 (-9) | 24 (-4) | 25 (-4) | 35 (2) | 39 (4) | 49 (9) | 63 (17) | 58 (14) | 47 (8) | 34 (1) | 27 (-3) | 22 (-6) | 16 (−9) |

| هطول الأمطار بوصة (mm) | 0.83 (21.1) | 0.77 (19.6) | 1.07 (27.2) | 0.25 (6.4) | 0.16 (4.1) | 0.09 (2.3) | 0.99 (25.1) | 0.94 (23.9) | 0.75 (19.1) | 0.79 (20.1) | 0.73 (18.5) | 0.92 (23.4) | 8٫29 (210٫6) |

| المصدر: [111] May 7, 2009 | |||||||||||||

| المصدر #2: [112] August 17, 2009 | |||||||||||||

المنظر العام للمدينة

السكان

| التعداد التاريخي | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| التعداد | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 240 | — | |

| 1880 | 1٬708 | 611٫7% | |

| 1890 | 3٬152 | 84٫5% | |

| 1900 | 5٬544 | 75٫9% | |

| 1910 | 11٬314 | 104٫1% | |

| 1920 | 29٬053 | 156٫8% | |

| 1930 | 48٬118 | 65٫6% | |

| 1940 | 65٬414 | 35٫9% | |

| 1950 | 106٬818 | 63٫3% | |

| 1960 | 439٬170 | 311٫1% | |

| 1970 | 581٬572 | 32٫4% | |

| 1980 | 789٬704 | 35٫8% | |

| 1990 | 983٬403 | 24٫5% | |

| 2000 | 1٬321٬045 | 34٫3% | |

| 2010 | 1٬445٬632 | 9٫4% | |

| 2020 | 1٬608٬139 | 11٫2% | |

| 2022 (تق.) | 1٬644٬409 | [3] | 2٫3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[115] 2010–2020[11] | |||

As of 2020, Phoenix was the fifth most populous city in the United States, with the census bureau placing its population at 1,608,139, edging out Philadelphia with a population of 1,567,872.[116] In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Phoenix had a population of 1,445,632 according to the 2010 United States census, the sixth largest city and still the most populous state capital in the United States.[117] Prior to the Great Recession, in 2006, Phoenix's population was 1,512,986, the fifth largest just ahead of Philadelphia.[117]

After leading the U.S. in population growth for over a decade, the sub-prime mortgage crisis, followed by the recession, led to a slowing in the growth of Phoenix. There were approximately 77,000 people added to the population of the Phoenix metropolitan area in 2009, which was down significantly from its peak in 2006 of 162,000.[118][119] Despite this slowing, Phoenix's population grew by 9.4% since the 2000 census (a total of 124,000 people), while the entire Phoenix metropolitan area grew by 28.9% during the same period. This compares with an overall growth rate nationally during the same time frame of 9.7%.[120][121] Not since 1940–50, when the city had a population of 107,000, had the city gained less than 124,000 in a decade. Phoenix's recent growth rate of 9.4% from the 2010 census is the first time it has recorded a growth rate under 24% in a census decade.[122] However, in 2016, Phoenix once again became the fastest growing city in the United States, adding approximately 88 people per day during the preceding year.[116]

The Phoenix Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) (officially known as the Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler MSA [123]), is one of 10 MSAs in Arizona, and was the 11th largest in the United States, with a 2018 U.S. census population estimate of 4,857,962, up from the 2010 census population of 4,192,887. Consisting of both Pinal and Maricopa counties, the MSA accounts for 65.5% of Arizona's population.[120][121] Phoenix only contributed 13% to the total growth rate of the MSA, down significantly from its 33% share during the prior decade.[122] Phoenix is also part of the Arizona Sun Corridor megaregion (MR), which is the tenth most populous of the 11 MRs, and the eighth largest by area. It had the second largest growth by percentage of the MRs (behind only the Gulf Coast MR) between 2000 and 2010.[124]

The population is almost equally split between men and women, with men making up 50.2% of city's citizens. The population density is 2,797.8 people per square mile, and the city's median age is 32.2 years, with only 10.9 of the population being over 62. 98.5% of Phoenix's population lives in households with an average household size of 2.77 people.

There were 514,806 total households, with 64.2% of those households consisting of families: 42.3% married couples, 7% with an unmarried male as head of household, and 14.9% with an unmarried female as head of household. 33.6% of those households have children below the age of 18. Of the 35.8% of non-family households, 27.1% have a householder living alone, almost evenly split between men and women, with women having 13.7% and men occupying 13.5%.

اعتبارا من 2020[تحديث], Phoenix has 590,149 dwelling units, with an occupancy rate of 87.2%. The largest segment of vacancies is in the rental market, where the vacancy rate is 14.9%, and 51% of all vacancies are in rentals. Vacant houses for sale only make up 17.7% of the vacancies, with the rest being split among vacation properties and other various reasons.[125]

The city's median household income was $47,866, and the median family income was $54,804. Males had a median income of $32,820 versus $27,466 for females. The city's per capita income was $24,110. 21.8% of the population and 17.1% of families were below the poverty line. Of the total population, 31.4% of those under the age of 18 and 10.5% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[126]

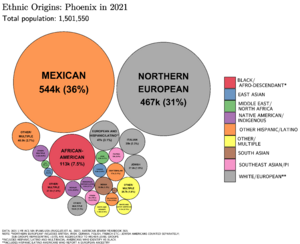

Ethnicity

| Racial composition | 1940[127] | 1970[127] | 1990[127] | 2010[128] | 2020[129] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (Non-Hispanic) | n/a | 81.3% | 71.8% | 46.5% | 42.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | n/a | 12.7% | 20.0% | 40.8% | 42.6% |

| Black or African American | 6.5% | 4.8% | 5.2% | 6.0% | 7.1% |

| Asian | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.7% | 3.0% | 3.9% |

| Mixed | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1.7% | 3.4% |

According to the 2020 census, the racial breakdown of Phoenix was as follows:[130]

- White: 49.7% (42.2% non-Hispanic)

- Black or African American: 7.8%

- Native American: 2.6%

- Asian: 4.1%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.2%

- Other race: 20.1%

- Two or more races: 15.5%

- Hispanic: 41.1%

According to the 2010 census, the racial breakdown of Phoenix was as follows:[131]

- White: 65.9% (46.5% non-Hispanic)

- Black or African American: 6.5% (6.0% non-Hispanic)

- Native American: 2.2%

- Asian: 3.2% (0.8% Indian, 0.5% Filipino, 0.5% Korean, 0.4% Chinese, 0.4% Vietnamese, 0.2% Japanese, 0.2% Thai, 0.1% Burmese)

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.2%

- Other race: 18.5%

- Two or more races: 3.6%

Phoenix's population has historically been predominantly white.[بحاجة لمصدر] From 1890 to 1970, over 90% of the citizens were white.[بحاجة لمصدر] In recent years, this percentage has dropped, reaching 65% in 2010. However, a large part of this decrease can be attributed to new guidelines put out by the U.S. Census Bureau in 1980, when a question regarding Hispanic origin was added to the census questionnaire. This has led to an increasing tendency for some groups to no longer self-identify as white, and instead categorize themselves as "other races".[127]

20.6% of the population of the city was foreign born in 2010. Of the 1,342,803 residents over five years of age, 63.5% spoke only English, 30.6% spoke Spanish at home, 2.5% spoke another Indo-European language, 2.1% spoke Asian or Islander languages, with the remaining 1.4% speaking other languages. About 15.7% of non-English speakers reported speaking English less than "very well". The largest national ancestries reported were Mexican (35.9%), German (15.3%), Irish (10.3%), English (9.4%), Black (6.5%), Italian (4.5%), French (2.7%), Polish (2.5%), American Indian (2.2%), and Scottish (2.0%).[132] Hispanics or Latinos of any race make up 40.8% of the population. Of these the largest groups are at 35.9% Mexican, 0.6% Puerto Rican, 0.5% Guatemalan, 0.3% Salvadoran, 0.3% Cuban.

Phoenix has the largest urban Native American population in Arizona. Phoenix has around 200 Dakota Sioux, approximately 100 Minnesota Chippewas, 100 Kiowas, about 175 Creeks, 100 Choctaws, several hundred Cherokees, several hundred Pueblos, and smaller numbers of Shawnees, Blackfeet, Pawnees, Cheyennes, Iroquois, Tlingit, Yakimas and other Native Americans from far away states.[133]

Hispanics are now the majority in Phoenix.[24] African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans live primarily in the southern portion of Phoenix, below the downtown district.[134]

According to the National Immigration Forum, the majority of Phoenix's immigrants are from Latin America: Mexico (196,941), Guatemala (5.093), El Salvador (2,980); Asia: India (10,128), Philippines (5.756), Vietnam (4,698); Africa: Ethiopia (1,157), Liberia (1,089), Sudan (1,067) and Europe: Bosnia and Herzegovina (2.944), Germany (2,847) and Romania (1,658).[135]

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, 66% of the population of the city identified themselves as Christians,[136][137] while 26% claimed no religious affiliation. The same study says other religions (including Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, and Hinduism) collectively make up about 7% of the population. In 2010, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives, which conducts religious census each ten years, 39% of those polled in Maricopa county considered themselves a member of a religious group. Of those who expressed a religious affiliation, the area's religious composition was reported as 35% Catholic, 22% to Evangelical Protestant denominations, 16% Latter-Day Saints (LDS), 14% to nondenominational congregations, 7% to Mainline Protestant denominations, and 2% Hindu. The remaining 4% belong to other religions, such as Buddhism and Judaism.

While the number of religious adherents increased by 103,000 during the decade, the growth did not keep pace with the county's overall population increase of almost three-quarters of million individuals during the same period. The largest aggregate increases were in the LDS (a 58% increase) and Evangelical Protestant churches (14% increase), while all other categories saw their numbers drop slightly or remain static. The Catholic Church had an 8% drop, while mainline Protestant groups saw a 28% decline.[138]

According to the 2022 Point-In-Time Homeless Count, there were 3,096 homeless people in Phoenix.[139]

Economy

Phoenix's early economy focused on agriculture and natural resources, especially the "5Cs" of copper, cattle, climate, cotton, and citrus.[18] With the opening of the Union Station in 1923, the establishment of the Southern Pacific rail line in 1926, and the creation of Sky Harbor airport in 1928, the city became more easily accessible.[140] The Great Depression affected Phoenix, but Phoenix had a diverse economy and by 1934 the recovery was underway.[141][142] At the conclusion of World War II, the valley's economy surged, as many men who had completed their military training at bases in and around Phoenix returned with their families. The construction industry, spurred on by the city's growth, further expanded with the development of Sun City. It became the template for suburban development in post-WWII America,[143] and Sun City became the template for retirement communities when it opened in 1960.[144][145] The city averaged a four percent annual growth rate over a 40-year period from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s.[23]

As the national financial crisis of 2007–10 began, construction in Phoenix collapsed and housing prices plunged.[146] Arizona jobs declined by 11.8% from peak to trough; in 2007 Phoenix had 1,918,100 employed individuals, by 2010 that number had shrunk by 226,500 to 1,691,600.[147] By the end of 2015, the employment number in Phoenix had risen to 1.97 million, finally regaining its pre-recession levels,[148] with job growth occurring across the board.[149]

اعتبارا من 2017[تحديث], the Phoenix MSA had a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of just under $243 billion. The top five industries were: real estate ($41.96), finance and insurance ($19.71), manufacturing ($19.91), retail trade ($18.64), and health care ($19.78). Government (including federal, state and local), if it had been a private industry, would have been ranked second on the list, generating $23.37 billion.[150]

In Phoenix, real estate developers face few constraints when planning and developing new projects.[151]

As of January 2016, 10.5% of the workforce were government employees, a high number because the city is both the county seat and state capital. The civilian labor force was 2,200,900, and the unemployment rate stood at 4.6%.[149]

Phoenix is home to four Fortune 500 companies: electronics corporation Avnet,[152] mining company Freeport-McMoRan,[153] retailer PetSmart,[154] and waste hauler Republic Services.[155] Honeywell's Aerospace division is headquartered in Phoenix, and the valley hosts many of their avionics and mechanical facilities.[156] Intel has one of their largest sites in the area, employing about 12,000 employees, the second largest Intel location in the country.[157] The city is also home to the headquarters of U-HAUL International, Best Western, and Apollo Group, parent of the University of Phoenix. Southwest is the largest carrier at Phoenix's Sky Harbor International Airport. Mesa Air Group, a regional airline group, is headquartered in Phoenix.[158]

The U.S. military has a large presence in Phoenix, with Luke Air Force Base in the western suburbs. The city was severely affected by the effects of the sub-prime mortgage crash. However, Phoenix has recovered 83% of the jobs lost due to the recession.[151]

Culture

Performing arts

The city has many performing arts venues, most of which are in and around downtown Phoenix or Scottsdale. The Phoenix Symphony Hall is home to the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra, the Arizona Opera and Ballet Arizona.[159] The Arizona Opera company also has intimate performances at its new Arizona Opera Center, which opened in March 2013.[160] Another venue is the Orpheum Theatre, home to the Phoenix Opera.[161] Ballet Arizona, in addition to the Symphony Hall, also has performances at the Orpheum Theatre and the Dorrance Theater. Concerts also regularly make stops in the area. The largest downtown performing art venue is the Herberger Theater Center, which houses three performance spaces and is home to two resident companies, the Arizona Theatre Company and the Centre Dance Ensemble. Three other groups also use the facility: Valley Youth Theatre, iTheatre Collaborative[162] and Actors Theater.[163]

Concerts take place at Footprint Center and Comerica Theatre in downtown Phoenix, Ak-Chin Pavilion in Maryvale, Gila River Arena in Glendale, and Gammage Auditorium in Tempe (the last public building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright).[164] Several smaller theaters including Trunk Space, the Mesa Arts Center, the Crescent Ballroom, Celebrity Theatre, and Modified Arts support regular independent musical and theater performances. Music can also be seen in some of the venues usually reserved for sports, such as the Wells Fargo Arena and State Farm Stadium.[165]

Several television series have been set in Phoenix, including Alice (1976–85), the 2000s paranormal drama Medium, the 1960–61 syndicated crime drama The Brothers Brannagan, and The New Dick Van Dyke Show from 1971 to 1974.

Museums

The valley has dozens of museums. They include the Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona Capitol Museum, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona Military Museum, Hall of Flame Fire Museum, Phoenix Police Museum, the Pueblo Grande Museum Archaeological Park, Children's Museum of Phoenix, Arizona Science Center, and the Heard Museum. In 2010, the Musical Instrument Museum opened their doors, featuring the biggest musical instrument collection in the world.[166] In 2015 the Children's Museum of Phoenix was recognized as one of the top three children's museums in the United States.[167]

Designed by Alden B. Dow, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Phoenix Art Museum was constructed in a single year, opening in November 1959.[168] The Phoenix Art Museum has the southwest's largest collection of visual art, containing more than 17,000 works of contemporary and modern art from around the world.[169][170][171] Interactive exhibits can be found in nearby Peoria's Challenger Space Center, where individuals learn about space, renewable energies, and meet astronauts.[172]

The Heard Museum has over 130,000 sq ft (12,000 m2) of gallery, classroom and performance space. Some of the museum's signature exhibits include a full Navajo hogan, the Mareen Allen Nichols Collection of 260 pieces of contemporary jewelry, the Barry Goldwater Collection of 437 historic Hopi kachina dolls, and an exhibit on the 19th-century boarding school experiences of Native Americans. The Heard Museum attracts about 250,000 visitors a year.[173]

Fine arts

The downtown Phoenix art scene has developed in the past decade. The Artlink organization and the galleries downtown have launched a First Friday cross-Phoenix gallery opening.[174] In April 2009, artist Janet Echelman inaugurated her monumental sculpture, Her Secret Is Patience, a civic icon suspended above the new Phoenix Civic Space Park, a two-city-block park in the middle of downtown. This netted sculpture makes the invisible patterns of desert wind visible. During the day, the 100-foot (30 m)-tall sculpture hovers high above heads, treetops, and buildings, creating what the artist calls "shadow drawings", which she says are inspired by Phoenix's cloud shadows. At night, the illumination changes color gradually through the seasons. Author Prof. Patrick Frank writes of the sculpture that "...this unique visual delight will forever mark the city of Phoenix just as the Eiffel Tower marks Paris."[175]

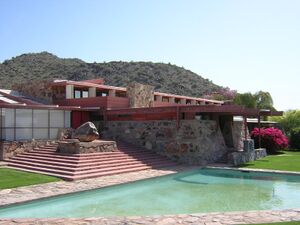

Architecture

Phoenix is the home of a unique architectural tradition and community. Frank Lloyd Wright moved to Phoenix in 1937 and built his winter home, Taliesin West, and the main campus for The Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.[176] Over the years, Phoenix has attracted notable architects who have made it their home and grown successful practices. These architectural studios embrace the desert climate, and are unconventional in their approach to the practice of design. They include the Paolo Soleri (who created Arcosanti),[177] Al Beadle,[178] Will Bruder,[179] Wendell Burnette,[180] and Blank Studio[181] architectural design studios. Another major force in architectural landscape of the city was Ralph Haver whose firm, Haver & Nunn, designed commercial, industrial and residential structures throughout the valley. Of particular note was his trademark, "Haver Home", which were affordable contemporary-style tract houses.[182]

Tourism

The tourist industry is the longest running of the top industries in Phoenix. Starting with promotions back in the 1920s, the industry has grown into one of the top 10 in the city.[183] With nearly 28,000 hotel rooms in over 175 hotels and resorts Phoenix sees over 19 million visitors each year, most of whom are leisure travelers. Sky Harbor Airport, which serves the Greater Phoenix area, serves about 45 million passengers a year, ranking it among the nation's 10 busiest airports.[184]

One of the biggest attractions of the Phoenix area is golf, with over 200 golf courses.[185] In addition to the sites of interest in the city, there are many attractions near Phoenix, such as Agua Fria National Monument, Arcosanti, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Lost Dutchman State Park, Montezuma's Castle, Montezuma's Well, and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Phoenix also serves as a central point to many of the sights around the state of Arizona, such as the Grand Canyon, Lake Havasu (where the London Bridge is located), Meteor Crater, the Painted Desert, the Petrified Forest, Tombstone, Kartchner Caverns, Sedona and Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff.

Other attractions and annual events

Due to its natural environment and climate, Phoenix has a number of outdoor attractions and recreational activities. The Phoenix Zoo is the largest privately owned, non-profit zoo in the United States. Since opening in 1962, it has developed an international reputation for its efforts on animal conservation, including breeding and reintroducing endangered species into the wild.[186] Right next to the zoo, the Phoenix Botanical Gardens were opened in 1939, and are acclaimed worldwide for their art and flora exhibits and educational programs, featuring the largest collection of arid plants in the U.S.[187][188][189] South Mountain Park, the largest municipal park in the U.S., is also the highest desert mountain preserve in the world.[190]

Other popular sites in the city are Japanese Friendship Garden, Historic Heritage Square, Phoenix Mountains Park, Pueblo Grande Museum, Tovrea Castle, Camelback Mountain, Hole in the Rock, Mystery Castle, St. Mary's Basilica, Taliesin West, and the Wrigley Mansion.[191]

Many annual events in and near Phoenix celebrate the city's heritage and its diversity. They include the Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show, the world's largest horse show; Matsuri, a celebration of Japanese culture; Pueblo Grande Indian Market, an event highlighting Native American arts and crafts; Grand Menorah Lighting, a December event celebrating Hanukah; ZooLights, a December evening event at the Phoenix Zoo that features millions of lights; the Arizona State Fair, begun in 1884; Scottish Gathering & Highland Games, an event celebrating Scottish heritage; Estrella War, a celebration of medieval life; and the Tohono O'odham Nation Rodeo & Fair, Oldest Indian rodeo in Arizona[192][193][194][195]

Cuisine

Phoenix is also renowned for its Mexican food, thanks to its large Hispanic population and its proximity to Mexico. Some of Phoenix's restaurants have a long history. The Stockyards steakhouse dates to 1947, while Monti's La Casa Vieja (Spanish for "The Old House") was in operation as a restaurant since the 1890s, but closed its doors November 17, 2014.[196][197] Macayo's (a Mexican restaurant chain) was established in Phoenix in 1946, and other major Mexican restaurants include Garcia's (1956) and Manuel's (1964).[198] The population boom has brought people from all over the nation, and to a lesser extent from other countries, and has since influenced the local cuisine. Phoenix boasts cuisines from all over the world, such as barbecue, Cajun/Creole, Greek, Hawaiian, Irish, Japanese, Italian, fusion, Persian, Indian (South Asian), Korean, Spanish, Thai, Chinese, southwestern, Tex-Mex, Vietnamese, Brazilian, and French.[199]

The first McDonald's franchise was sold by the McDonald brothers to a Phoenix entrepreneur in 1952. Neil Fox paid $1,000 for the rights to open an establishment based on the McDonald brothers' restaurant.[200] The hamburger stand opened in 1953 on the southwest corner of Central Avenue and Indian School Road, on the growing north side of Phoenix, and was the first location to sport the now internationally known golden arches, which were initially twice the height of the building. Three other franchise locations opened that year, two years before Ray Kroc purchased McDonald's.[200]

الرياضة

الحدائق

الإعلام

الحكومة

التعليم

النقل

النقل الجوي

النقل عامة

الدراجات

الشوارع الرئيسية

مدن شقيقة

ترتبط مدينة فينكس بعلاقات مع عشر مدن شقيقة:[201]

انظر أيضا

المصادر

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved أكتوبر 29, 2021.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved مايو 5, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. مايو 29, 2022. Retrieved مايو 31, 2022.

- ^ "List of 2020 Census Urban Areas". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved يناير 8, 2023.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved أغسطس 22, 2021.

- ^ "Total Gross Domestic Product for Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org.

- ^ "Phoenix, Arizona Mining Claims And Mining Mines | The Diggings™".

- ^ "La mayor planta solar del mundo se construirá en Arizona". El País (in الإسبانية). فبراير 21, 2008. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved يوليو 26, 2023.

- ^ Watahomigie, Lucille, Jorigine Bender, Akira Yamamoto, University of Los Angeles. Hualapai reference grammar. 1982.

- ^ "The 10 Most Populated State Capitals". سبتمبر 3, 2020.

- ^ أ ب "QuickFacts: Phoenix city, Arizona". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved أغسطس 19, 2021.

- ^ "Phoenix QuickFacts from US Census Bureau". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved سبتمبر 12, 2021.

- ^ Brunn, S.D.; Zeigler, D.J.; Hays-Mitchell, M.; Graybill, J.K. (2020). Cities of the World: Regional Patterns and Urban Environments. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-5381-2635-6. Retrieved مارس 23, 2023.

- ^ "County and City Data Book: 2007" (PDF) (14 ed.). U.S. Census Bureau. 2007. p. 712. Archived from the original (PDF) on يناير 16, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ Villarreal, Phil (فبراير 14, 2018). "Arizona turns 106 Wednesday" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). KNXV. Retrieved فبراير 14, 2018.

- ^ "Farming and Ranching". arizonaexperience.org. Archived from the original on ديسمبر 28, 2013. Retrieved فبراير 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Marin, Ph.D., Christine. "A Short History of South Phoenix from 1865 to the early 1930s". barriozona. Archived from the original on مارس 4, 2016. Retrieved مارس 22, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "The Five C's – An Arizona History Lesson". azsos.gov. Archived from the original on أبريل 29, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ Bernard, Richard M. & Rice, Bradley R. (2014). Sunbelt Cities: Politics and Growth since World War II. University of Texas Press. p. 315. ISBN 9780292769823.

- ^ Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. (2006). "World Map of Köppen–Geiger Climate Classification" (PDF). Climate Change & Infectious Diseases Group, Institute for Veterinary Public Health. University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna. Archived (PDF) from the original on فبراير 5, 2009. Retrieved يناير 30, 2018.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (أكتوبر 11, 2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product by County and Metropolitan Area | FRED | St. Louis Fed". fred.stlouisfed.org. Retrieved فبراير 6, 2024.

- ^ أ ب "Why Phoenix?". AZ International Growth Group. 2016. Retrieved مارس 28, 2016.

- ^ أ ب Backer, Kyle (أغسطس 31, 2021). "Hispanic population is now the majority in Phoenix, Census shows". AZ Big Media.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض "History of Phoenix". City of Phoenix. Archived from the original on أبريل 15, 2014. Retrieved أبريل 15, 2014.

- ^ Trimble, Marshall (1988). Arizoniana. American Traveler Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-885590-89-3.

- ^ "Prehistoric Desert Peoples: The Hohokam". Desert USA. Archived from the original on مارس 17, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ Trimble 1988, p. 105.

- ^ أ ب Montero 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Seymour, Deni J. "Delicate Diplomacy on a Restless Frontier: Seventeenth-Century Sobaipuri Social And Economic Relations in Northwestern New Spain, Part I". New Mexico Historical Review (2007b): 82.

- ^ "Xalychidom Piipaash (Maricopa) People". Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. Archived from the original on أغسطس 5, 2018. Retrieved فبراير 17, 2014.

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb, ed. (1906). "The Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico". Bureau of American Ethnology, Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on فبراير 18, 2014. Retrieved مارس 24, 2016.

- ^ "Gila River Indian Community History". Gila River Indian Community. Archived from the original on أكتوبر 9, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 24, 2014.

- ^ "Xalychidom Piipaash (Maricopa) People". Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community. Archived from the original on أغسطس 5, 2018. Retrieved فبراير 17, 2014.

- ^ "Maricopa Tribe". يوليو 9, 2011. Retrieved فبراير 17, 2014.

- ^ McIntyre, Allan (2008). The Tohono O'odham and Pimeria Alta. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738556338.

- ^ "San Xavier del Bac Mission-Tohono O'odham". San Xavier Mission. Archived from the original on فبراير 28, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 24, 2014.

- ^ "Tohono O'odham History". Retrieved فبراير 24, 2014.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2012). The Encyclopedia of the Mexican–American War: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-85109-854-5.

- ^ Fudala, Joan (2001). Historic Scottsdale: A Life from the Land. HPN Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-893619-12-8. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "Tempe History Timeline". Tempe.gov. Archived from the original on يناير 5, 2011. Retrieved يناير 31, 2013.

- ^ "Survey Details – BLM GLO Records". glorecords.blm.gov.

- ^ "Arizona Water Pioneers – Part 1 | Jack Swilling". أبريل 30, 2019. Archived from the original on يوليو 14, 2020. Retrieved يوليو 14, 2020.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. p. 14.

- ^ "History". Greater Phoenix Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved أكتوبر 9, 2015.

- ^ Garcia, Kathleen, ed. (2008). Early Phoenix. Arcadia Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0738548395.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Phoenix Carnegie Library and Library Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on أبريل 7, 2016. Retrieved مارس 22, 2016.

- ^ "Reclamation Act/Newlands Act of 1902". Center for Columbia River History. Archived from the original on مارس 3, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "Theodore Roosevelt Dam". Salt River Project. Archived from the original on مارس 3, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "GNIS Detail: Theodore Roosevelt Dam". USGS. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved يناير 5, 2017.

- ^ "GNIS Detail: Theodore Roosevelt Lake". USGS. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved يناير 5, 2017.

- ^ "Arizona". History.com. Archived from the original on مارس 4, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "President William Howard Taft's veto of H.J. Res. 14 to admit the territories of New Mexico and Arizona as States into the Union, August 15, 1911". National Archives. Archived from the original on أبريل 3, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "1935 and The Farm – Sky Harbor's Early Years and Memories". skyharbor.com. أغسطس 30, 1930. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "Arizona scenic drive: Globe to Safford". Arizona Republic. أكتوبر 2, 2015. Archived from the original on مارس 20, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ أ ب Thompson, Clay (1999). Valley 101: A Slightly Skewed Guide to Living in Arizona. Primer Publishers. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-935810-71-4.

- ^ "Scottsdale Airport History". scottsdaleaz.gov. Retrieved فبراير 19, 2014.

- ^ Manning, Thomas A. (2005). History of Air Education and Training Command, 1942–2002. Randolph AFB, Texas: Office of History and Research, Headquarters, AETC. ISBN 978-1-178-48983-5.

- ^ "1940s in Arizona: Internment camps and high-tech firms". Arizona Republic. مايو 14, 2015. Archived from the original on مارس 23, 2016. Retrieved مارس 22, 2016.

- ^ Boone, Christopher G.; Fragkias, Michail, eds. (2012). Urbanization and Sustainability. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 64–65. ISBN 9789400756663.

- ^ "20th Century". Arizona Edventures. Archived from the original on فبراير 22, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ Needham, Andrew (2014). Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 84.

- ^ Needham, Andrew (2014). Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 86.

- ^ Needham, Andrew (2014). Power Lines: Phoenix and the Making of the Modern Southwest. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 87.

- ^ "1960s trends in Arizona". Arizona Republic. سبتمبر 1, 2011. Archived from the original on مارس 4, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ Rex, Tom R. "Development of Metropolitan Phoenix: Historical, Current and Future Trends" (PDF). History.com. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on مارس 24, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ VanderMeer 2010, p. 42.

- ^ "Phoenix Corporate Center". Emporis. Archived from the original on أكتوبر 19, 2012. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix City Square". Emporis. Archived from the original on فبراير 21, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Phoenix Financial Center a.k.a. Western Savings and Loan". ModernPhoenix.net. Archived from the original on فبراير 22, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "Suns Timeline". National Basketball Association. Archived from the original on فبراير 5, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "Season Review 68–69" (PDF). National Basketball Association. p. 122. Archived from the original (PDF) on فبراير 8, 2012. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "Season Review 92–93" (PDF). National Basketball Association. p. 170. Archived from the original (PDF) on فبراير 8, 2012. Retrieved فبراير 5, 2014.

- ^ "History". Central Arizona Project. Archived from the original on مارس 3, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "Morris Udall Papers – Central Arizona Project". University of Arizona. Archived from the original on مارس 5, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "History of the Diocese of Phoenix". The Roman Catholic Diocese of Phoenix. Archived from the original on فبراير 27, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ Luckingham 1995, pp. 235–237.

- ^ "Valley Arts Guide". Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on مايو 15, 2016. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "Chase Tower". Emporis. Archived from the original on نوفمبر 6, 2012. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ "First Woman to Supreme Court". History Central. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ "Arizona Centennial". The Arizona Republic/AZCentral.com. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ "Arizona Centennial". The Arizona Republic/AZCentral.com. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ "John C. Lincoln Timeline – 1990s". John C. Lincoln Health Network. Archived from the original on فبراير 28, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix City Hall". SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved فبراير 27, 2014.

- ^ Woolsey, Matt (أكتوبر 31, 2007). "In Pictures: America's Fastest-Growing Cities from". Forbes. Retrieved يونيو 30, 2010.

- ^ Myers, Amanda Lee (أبريل 10, 2008). "Feds OK naming Phoenix peak for soldier". USA Today. Retrieved فبراير 20, 2014.

- ^ Snow, Mary; Acosta, Jim (فبراير 17, 2009). "Obama expected to announce foreclosure plan". CNN. Retrieved مايو 22, 2010.

- ^ Loomis, Brandon (يونيو 1, 2023). "Arizona will halt new home approvals in parts of metro Phoenix as water supplies tighten". azcentral.com. USA TODAY Network. Retrieved يونيو 1, 2023.

- ^ "Feature Detail Report for: Phoenix". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on يناير 9, 2017. Retrieved مارس 19, 2016.

- ^ "Phoenix Mountain Overview". summitpost.org. Retrieved مارس 5, 2014.

- ^ James W. Elmore (1985). A Guide to the architecture of Metro Phoenix. p. 20.

- ^ Paul M. Torrens, "Simulating sprawl." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96.2 (2006): 248–275.

- ^ Carol E. Heim, "Leapfrogging, urban sprawl, and growth management: Phoenix, 1950–2000." American Journal of Economics and Sociology 60.1 (2001): 245–283.

- ^ "A hydra in the desert". The Economist. يوليو 15, 1999. Retrieved فبراير 16, 2019.

- ^ Walters, Joanna (مارس 20, 2018). "Plight of Phoenix: how long can the world's 'least sustainable' city survive?". The Guardian. Retrieved فبراير 15, 2019.

- ^ White, Kaila (أكتوبر 6, 2016). "'Onion' article mocks Phoenix's suburban sprawl". Arizona Republic. Retrieved فبراير 15, 2019.

- ^ Egan, Timothy (ديسمبر 29, 1996). "Urban Sprawl Strains Western States". The Seattle Times. Retrieved فبراير 16, 2019.

- ^ "Phoenix (city) QuickFacts". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on مايو 21, 2012. Retrieved مارس 5, 2014.

- ^ "Philadelphia (city) Quickfacts". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on يونيو 24, 2011. Retrieved مارس 5, 2014.

- ^ "Arizona does not need daylight saving time". Arizona Daily Star. مايو 19, 2005. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 29, 2007. Retrieved يونيو 19, 2012.

- ^ "Village Planning Committees". City of Phoenix. Archived from the original on مارس 25, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "The Village Planning Handbook" (PDF). City of Phoenix. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on مارس 27, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "ReinventPHX District Profile: Uptown" (PDF). City of Phoenix. Archived from the original (PDF) on يناير 2, 2017. Retrieved أكتوبر 22, 2016.

- ^ "The Wildlife of the Phoenix Mountain Preserves". phoenix.gov. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 19, 2015. Retrieved سبتمبر 5, 2015.

- ^ "Living With Wildlife – Arizona Wildlife". Arizona Game and Fish Department. Archived from the original on فبراير 22, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 10, 2014.

- ^ Radamaker, Kurt A.; Corman, Troy E. (سبتمبر 15, 2011). "Status of the Rosy-faced Lovebird in Phoenix, Arizona". Arizona Field Ornithologists. Retrieved سبتمبر 4, 2014.

- ^ Clark, Greg. "Peach-faced Lovebird Range Expansion Data in Greater Phoenix, Arizona Area". Retrieved فبراير 27, 2011.

- ^ "Common Snakes of the Phoenix Area". Phoenix Snake Removal. Retrieved فبراير 10, 2014.

- ^ "Sonoran Desert Region Flora – Maricopa County". Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. Archived from the original on فبراير 22, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 10, 2014.

- ^ "Natural Vegetation of Arizona". University of Arizona Library. Archived from the original on فبراير 24, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 10, 2014.

- ^ "Average Weather for Phoenix, AZ - Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. Retrieved مايو 7, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ "CLIMATE OF PHOENIX, ARIZONA: An Abridged On-Line Version of NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS WR-177". Arizona State University. Retrieved أغسطس 17, 2009.

- ^ "Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2016 Inflation-adjusted Dollars)". American Fact Finder. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on فبراير 14, 2020. Retrieved مارس 21, 2018.

- ^ "Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months". American Fact Finder. US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on فبراير 14, 2020. Retrieved مارس 21, 2018.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved يونيو 4, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Phoenix now the 5th-largest city in the US, census says". Fox News Channel. مايو 25, 2017. Archived from the original on مايو 25, 2017. Retrieved مايو 27, 2017.

- ^ أ ب Bui, Lynh (مارس 13, 2011). "Arizona Republic: "Phoenix drops to sixth largest city."". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved يونيو 19, 2012.

- ^ Van Velzer, Ryan. "Census estimates show sharp drop in Arizona's population growth". Tucson Sentinel. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ El Nasser, Haya. "Most major U.S. cities show population declines". US Today. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Arizona Statistics: Taking a Look at Census 2010". phoenix.about.com. Archived from the original on أبريل 12, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Large Metropolitan Statistical Areas – Population: 1990 to 2010" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on مايو 10, 2012. Retrieved مارس 19, 2014.

- ^ أ ب Cox, Wendell. "Phoenix Population Counts Lower than Expected". newgeography.com. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ OMB Bulletin 18-04, September 14, 2018

- ^ "Megaregions". america2050. Archived from the original on مايو 16, 2017. Retrieved فبراير 10, 2014.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on فبراير 12, 2020. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2008–2012 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on فبراير 12, 2020. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Arizona – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on أغسطس 12, 2012. Retrieved مارس 2, 2014.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts – Phoenix (city), Arizona". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on مايو 21, 2012.

- ^ "2020 Census". 2020.

- ^ "Phoenix city, Arizona Demographics and Housing 2020 Decennial Census". Statesman Journal.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin: 2010". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on فبراير 12, 2020. Retrieved مارس 2, 2014.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on مارس 16, 2015. Retrieved مارس 19, 2014.

- ^ ""2. Phoenix" in "Urban Indians of Arizona: Phoenix, Tucson, and Flagstaff" on University of Arizona Press". open.uapress.arizona.edu.

- ^ "Phoenix - Indigenous, Settlers, Pioneers". Britannica.

- ^ "PHOENIX: AN IMMIGRATION SNAPSHOT" (PDF).

- ^ Major U.S. metropolitan areas differ in their religious profiles, Pew Research Center

- ^ "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. مايو 12, 2015.

- ^ "2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study". The Association of Religious Data Archives. Archived from the original on أبريل 29, 2014. Retrieved مارس 19, 2014.

- ^ "Human Services Homeless Information". www.phoenix.gov. Retrieved مارس 11, 2023.

- ^ VanderMeer 2010, p. 44.

- ^ VanderMeer 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Luckingham 1995, p. 102.

- ^ "Levittown: the Archetype for Suburban Development". American History Magazine. أكتوبر 2007.

- ^ "Opening day of first model homes in Sun City". Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records. Archived from the original on أبريل 6, 2016. Retrieved مارس 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Family: A Place in the Sun". Time. أغسطس 3, 1962. Archived from the original on فبراير 23, 2016. Retrieved مارس 23, 2016.

- ^ Vest, Marshall J. (يناير 2009). "Economic Outlook for 2009–2010: Riding Out the Storm". Arizona's Economy. Eller College of Management (Winter): 2.

- ^ "Historical Data". W.P. Carey School of Business. Archived from the original on مارس 4, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ Toll, Eric Jay (يناير 22, 2016). "Arizona ends 2015 on strong job growth". Phoenix Business Journal. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ أ ب "Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale, AZ". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Archived from the original on مارس 1, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "Regional Date GDP and Personal Income for Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ Metropolitan Statisitical Area". Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2017. Retrieved أكتوبر 9, 2019.

- ^ أ ب Hudgins, Matt. "Some Investors Bid High on Phoenix Office Market". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved نوفمبر 10, 2015.

- ^ "Avnet Global Headquarters". Colliers International. Archived from the original on مارس 29, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "Freeport-McMoRan – Who We Are". fcx.com. Archived from the original on مارس 28, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ "PetSmart Company Information". PetSmart. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ "Fortune 500 2012: States: Arizona". CNN. مايو 21, 2012. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ "A History Of... Tim Mahoney". Honeywell Aerospace. Archived from the original on أبريل 2, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "Intel in Arizona". Intel.com. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ "Facts". Mesa Airlines. Archived from the original on مارس 7, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "Symphony Hall". phoenix.about.com. Archived from the original on فبراير 21, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 8, 2014.

- ^ "$5.2M Arizona Opera Center". frontdoor news. مارس 22, 2013. Archived from the original on فبراير 22, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 8, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix Opera". phoenixopera.org. Retrieved فبراير 8, 2014.

- ^ "2013–14 Season". iTheatre Collaborative. Archived from the original on فبراير 24, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 8, 2014.

- ^ "About Herberger Theater Center". herbergertheater.org. Retrieved فبراير 8, 2014.

- ^ "ASU Gammage from the beginning". Arizona State University. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix Theatre". phoenix-theater.com. Retrieved فبراير 16, 2014.

- ^ Nilsen, Richard (أبريل 18, 2010). "Music Instrument Museum opens in Phoenix". Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on مايو 15, 2016. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "The 25 Best American Children's Museums". Early Childhood Education Zoon. أكتوبر 9, 2015. Retrieved فبراير 7, 2019.

- ^ "History & Mission". phxart.org. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 5, 2015. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix Art Museum". VisitPhoenix. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix Art Museum – Permanent Collection". phoenix.about.com. Archived from the original on أبريل 12, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ "Major Metro Phoenix Area Museums". phoenixasap.com. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ "AZ Challenger Space Center". Azchallenger.org. Retrieved يونيو 24, 2013.

- ^ "Heard Museum: Welcome". Heard Museum. Retrieved مارس 20, 2014.

- ^ "Art Detour at 30: 5 pioneers who built the downtown Phoenix studio scene". The Arizona Republic (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved فبراير 28, 2019.

- ^ Frank, Patrick (2011). Prebles' Artformes. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-205-79753-0.

- ^ Herberholz, B (1997). "Taliesin West and Frank Lloyd Wright". Arts and Activities. 122 (3): 30–32.

- ^ "Paolo Soleri : architect biography". Architecture.sk. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 14, 2014. Retrieved ديسمبر 1, 2014.

- ^ "Modern Architecture: Al Beadle". Historic Phoenix. Archived from the original on ديسمبر 11, 2013. Retrieved ديسمبر 1, 2014.

- ^ Snider, Bruce D. "Hall of Fame: Will Bruder, AIA". Residential Architect. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 23, 2013. Retrieved ديسمبر 1, 2014.

- ^ "Wendell Burnette Architects" (PDF). ASU-Herberger Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on مايو 19, 2016. Retrieved ديسمبر 1, 2014.

- ^ Drueding, Meghan (مايو 8, 2008). "xeros residence, phoenix: project of the year". Residential Architect. Retrieved ديسمبر 22, 2014.

- ^ King, Alison (2011). "Ralph Haver: Everyman's Modernist". The Modern Phoenix. Archived from the original on أبريل 1, 2014. Retrieved ديسمبر 1, 2014.

- ^ Towne, Douglas (ديسمبر 2010). "Phoenix in the 1920s". Phoenix Magazine: 88.

- ^ "Phoenix Facts". Visit Phoenix. visitphoenix.com. 2023. Archived from the original on مايو 6, 2023. Retrieved مايو 13, 2023.

- ^ "About Phoenix- Fun Facts". visitphoenix.com. Archived from the original on فبراير 24, 2014. Retrieved فبراير 11, 2014.

- ^ "History of the Zoo". The Phoenix Zoo. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "About the Garden". Desert Botanical Garden. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "Desert Botanical Garden". About.com. Archived from the original on مارس 22, 2014. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "13 must-see botanical gardens". Mother Nature Network. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "South Mountain Park and Preserve". Discover Phoenix Arizona. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 11, 2013. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix Points of Pride". City of Phoenix. Archived from the original on سبتمبر 14, 2015. Retrieved مارس 20, 2016.

- ^ "Annual Phoenix Events". Discover Phoenix. Archived from the original on مارس 27, 2014. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "Heritage & Cultural". Arizona Guide. Archived from the original on أبريل 13, 2014. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "50th Scottish Gathering & Highland Games". The Caledonian Society of Arizona. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "Estrella War XXX: Newcomer's Guide". EstrellaWar.org. أغسطس 8, 2013. Archived from the original on فبراير 10, 2014. Retrieved مارس 21, 2014.

- ^ "Stockyards Steakhouse". stockyardssteakhouse.com. Archived from the original on أكتوبر 8, 2013. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ Edelen, Amy (نوفمبر 4, 2014). "Tempe's iconic Monti's La Casa Vieja closing Nov. 17". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved يناير 27, 2016.

- ^ "History". Macayo's. Archived from the original on مارس 27, 2014. Retrieved مارس 20, 2014.

- ^ "Phoenix Restaurants by Cuisine Type". phoenixrestaurants.com. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ أ ب "McDonald Brothers". Around Arizona. Retrieved فبراير 9, 2014.

- ^ Sister Cities information obtained from the Phoenix Sister Cities Commission." Retrieved on April 21, 2006.

وصلات خارجية

![]() تعريفات قاموسية في ويكاموس

تعريفات قاموسية في ويكاموس

![]() كتب من معرفة الكتب

كتب من معرفة الكتب

![]() اقتباسات من معرفة الاقتباس

اقتباسات من معرفة الاقتباس

![]() نصوص مصدرية من معرفة المصادر

نصوص مصدرية من معرفة المصادر

![]() صور و ملفات صوتية من كومونز

صور و ملفات صوتية من كومونز

![]() أخبار من معرفة الأخبار.

أخبار من معرفة الأخبار.

- Official Government Website

- Greater Phoenix Chamber of Commerce

- Greater Phoenix Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Phoenix Public Library

- The Arizona Republic — daily newspaper serving Phoenix area

- USGS—Phoenix Elevation

فينكس، أريزونا travel guide from Wikitravel

معلومات متعلقة

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use mdy dates from October 2023

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible nickname list

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Use American English from January 2019

- All Wikipedia articles written in American English

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2020

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2023

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2017

- Pages with empty portal template

- مدن في أريزونا

- Communities in the Sonoran Desert

- مقاطعة ماركوبا، أريزونا

- Phoenix metropolitan area

- فينكس، أريزونا

- County seats in Arizona

- Settlements established in 1868

- UFO-related locations

- مدن الولايات المتحدة

- صفحات مع الخرائط