پانونيا

| Provincia Pannonia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 AD–107 AD | |||||||||

Province of Pannonia highlighted (red) within the Roman Empire (white) | |||||||||

| العاصمة | Carnuntum,[1] Sirmium,[2] Savaria,[3] Aquincum,[4] Poetovio[5] or Vindobona[6] | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• Established | 20 AD | ||||||||

• Division of Pannonia | Between the years 102 and 107, Trajan divided Pannonia into Pannonia Superior (western part with the capital Carnuntum), and Pannonia Inferior (eastern part with the capitals in Aquincum and Sirmium) 107 AD | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Pannonia ( /pəˈnoʊniə/, لاتينية: [panˈnɔnia]) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now western Hungary, western Slovakia, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia, northern Slovenia, and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina.

الاسم

Julius Pokorny believed the name Pannonia is derived from Illyrian, from the Proto-Indo-European root *pen-, "swamp, water, wet" (cf. English fen, "marsh"; Hindi pani, "water").[7]

Pliny the Elder, in Natural History, places the eastern regions of the Hercynium jugum, the "Hercynian mountain chain", in Pannonia and Dacia (now Romania).[8] He also gives us some dramaticised description[9] of its composition, in which the proximity of the forest trees causes competitive struggle among them (inter se rixantes). He mentions its gigantic oaks.[10] But even he—if the passage in question is not an interpolated marginal gloss—is subject to the legends of the gloomy forest. He mentions unusual birds, which have feathers that "shine like fires at night". Medieval bestiaries named these birds the Ercinee. The impenetrable nature of the Hercynia Silva hindered the last concerted Roman foray into the forest, by Drusus, during 12–9 BC: Florus asserts that Drusus invisum atque inaccessum in id tempus Hercynium saltum (Hercynia saltus, the "Hercynian ravine-land")[11] patefecit.[12]

الخلفية

The Illyrians (Illyrii) were the first known people to inhabit the region. Their immigration took place during the late Bronze Age and the early Iron Age. The leading class of the indigenous population was expelled or killed, while the majority of the population was obliged to pay tax. The locals were massacred in only some places, so the old crafts and traditions endured. The culture of the region changed with the arrival of more Illyrian warriors, who even engaged in conflicts with the earlier arrived Illyrians.[13] The Illyrians in Pannonia were distinguished by the Romans as Pannonians (Pannonii).

Pannonia was connected to the Italian Peninsula by trade since the 2nd millennium BC. Amber from Jutland and East Prussia arrived to there through Transdanubia. Later in the 1st millennium BC, industrial products of the Veneti and Etruscans, and from the Este culture were brought here.[14]

Liber Historiae Francorum states, that following the fall of Troy (2300 BC) 12.000 Trojans led by Chiefs Priam and Antenor moved to Pannonia and founded a city called Sicambria.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the Iron Age, new conqueror peoples arrived, beginning with the Cimmerians who flew from the Scythians. The Scythians afterwards settled in great numbers.[13] Unlike others, they fought with iron weapons and had an advanced aristocracy.[15]

The influx of the Celtic tribes from the 4th century BC[15][16] eventually broke the domination of the Illyrians and Scythians. Part of the Illyrians retreated to the Balkans, while the bigger part of the defeated folk stayed on their lands and were assimilated by time. The Celts had superior agriculture and industry. Though they didn't get to establish states because of their scattered disposition, some tribes minted their own coins.[15] These coins resembled the Macedonian tetradrachms, later the Roman denarii.[14]

The Celtic invasion broke trade between the inhabitants of Italy and the Germanic peoples through Transdanubia. There was no big rupture with the inhabitants of Transdanubia, however. Aes signatum ingots were in use in Pannonia as long as the 1st century BC. Since the 2nd century BC, denarii were in extensive use.[14] For one and a half century prior to the Roman invasion, the Celts and the Romans were in stable trade relations. Roman merchants brought industrial products in exchange for slaves and raw materials.[17]

الفتح الروماني

The tribes of the Pannonians, to which no army of the Roman people had ever penetrated before my principate, having been subdued by Tiberius Nero who was then my stepson and my legate, I brought under the sovereignty of the Roman people, and I pushed forward the frontier of Illyricum as far as the bank of the river Danube. An army of Dacians which crossed to the south of that river was, under my auspices, defeated and crushed, and afterwards my own army was led across the Danube and compelled the tribes of the Dacians to submit to the orders of the Roman people.

The strengthening of the empire necessarily led to the annexation of new territories.[19] This process was slow but enthused by the ideology of Pax Romana.[20] In the aftermath of the Second Punic War, Rome solidified control over the southern part of Illyria and looked to link it up with Northern Italy by land. This goal required expansion towards modern-day Hungary.[21] In 183 BC, the Senate established the colonia of Aquileia to make Pannonia economically closer. Later, the rich Aquileian lords played a big part in the region's economy.[22] The hazard caused by the tribe of the Scordisci was an important reason for the conquest of the area. The Dardani and Thracians posed similar threats. Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus was the first to conduct an attack against the Scordisci. The Macedonians urged them to raid Pannonia and King Perseus reached an alliance with them.[20] In the middle of the 2nd century BC, the Dalmatians and Scordisci got defeated and a Roman army first stepped on the land of what will be the province of Pannonia; they reached Siscia. Rome, however didn't intend to conquer this land yet, just punish the local raiders. These expeditions, however, successfully connected Italy and Illyria by land. In 119 BC, the Romans again advanced as far as Siscia.[21] Mithridates VI Eupator looked to forge an alliance between Pontus and the Pannonians.[23]

Roman expansion here paused for a time and holdings at the Danube were lost in the turmoil caused by the Social War. Other problems, such as the population shift related to the Cimbri and the strong resistance of the Iapydes kept back the advancement of this regionally important front line.[21] Even during the life of Julius Caesar, the subjugation of Gaul came first and the unruly Dalmatians couldn't be dealt with due to the conflict with Pompey the Great.[24]

Scribonius Curio's army reached the Danube probably through the Morava Valley. Following the Maritsa, another general gained territories between the Aegean Sea and the Lower Danube in 70 BC.[20]

Octavian maintained large armies to keep the balance with Mark Antony, so to put a better face on his activity, he pursued a foreign policy of expanding Roman dominions northward.[25] In 16 BC, he conquered the Kingdom of Noricum.[26] The Alpine tribes were let alone.[22]

There were multiple strategic reasons for the invasion of Pannonia. The Romans wanted to obstruct the Dacian expansion into the area.[19][27] The Romans wanted to pacify the tribe of the Scordisci based in southern Pannonia whose attacks slowed the seizure of the Balkans[19] and sought to gain a wider connection to the Balkan provinces by land.[27] The conquest of lands up to the Danube would not only establish a better defendable border,[27][28] but would also allow the legions to move more freely and receive supplies more swiftly.[28]

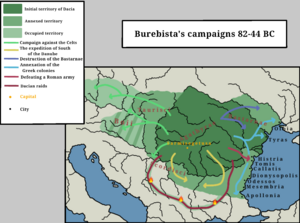

From 35 BC, the Pannonians started to aid the Dalmatians in their strife against Rome, so Rome began expanding more aggressively into the area, capturing Siscia (now Sisak, Croatia).[16] Between 12 and 9 BC Augustus pushed the border to the Danube[19][29][30] and the land became part of the province of Illyricum.[31] Only the Thracian kingdom remained a client state.[32] The Dacian king Cotiso died in 9 BC.[33]

الحكم الروماني

التأسيس

In 7 AD, the Great Illyrian Revolt erupted as the subdued population of Illyricum rose up against Roman rule. The rebels were eventually defeated after a hard-fought campaign lasting 2 years led by Germanicus and future-emperor Tiberius.[29]

In 10 AD, Pannonia was established as a separate province. Due to the proximity of hostile barbarian tribes, many fortifications were built on the border and large number of legionaries and auxiliaries were stationed in the region.[29]

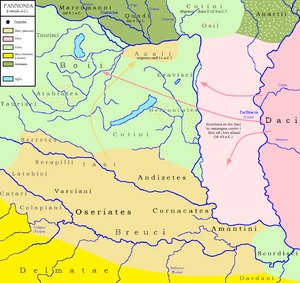

Some time between the years 102 and 107, between the first and second Dacian wars, Trajan divided the province into Pannonia Superior (western part with the capital Carnuntum), and Pannonia Inferior (eastern part with the capitals in Aquincum and Sirmium[34]). According to Ptolemy, these divisions were separated by a line drawn from Arrabona in the north to Servitium in the south; later, the boundary was placed further east. The whole country was sometimes called the Pannonias (Pannoniae).

السرمت

The province of Pannonia was threatened from the east by the Scythic Sarmatians. During the conquest of Transdanubia, Sarmatian peoples, most notably the Iazyges occupied the Danube–Tisza Interfluve, vassallizing the Dacian-Celtic elements in the area and trading with both the Romans and other Celts. This was beneficial for the Roman Empire because the Sarmatians counterbalanced Dacia. Nonetheless, their looting campaigns through the frozen Danube[35] resulted in large amounts of soldiers being drawn to that segment of the border in the 180s. In the 190s, guard posts, bridgeheads, earth forts and later stone forts were constructed at Aquincum, Albertfalva, Nagytétény, Adony, Százhalombatta, Dunaújváros and other settlements.[36]

حروب الماركوماني

The one and a half century of relative peacefulness in the province was ended by an invasion of the Marcomanni, Quadi and Iazyges during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. The struggle was made even more difficult by the ravaging Antonine Plague, in which the emperor himself died at Vindobona, Pannonia Superior.[37] Marcus Aurelius constructed the limes.[38]

الأزمة والترسيخ

After the death of Marcus Aurelius, his son Commodus continued to fight along the limes, but governed the empire superficially. External attacks made possible Septimius Severus's ascension to the throne, who was governor of Pannonia Superior. Thanks to this soldier-emperor, peace returned for half a century. After the fall of the Severan dynasty, internal and external conflict restarted. The ambient barbarian peoples were able to penetrate in multiple parts of the border. In 260 Roxolani invaded the province.[38]

الإدارة

Pannonia Superior was under the consular legate, who had formerly administered the single province, and had three legions under his control. Pannonia Inferior was at first under a praetorian legate with a single legion as the garrison; after Marcus Aurelius, it was under a consular legate, but still with only one legion. The frontier on the Danube was protected by the establishment of the two colonies Aelia Mursia and Aelia Aquincum by Hadrian.

Under Diocletian, a fourfold division of the country was made:

- Pannonia Prima in the northwest, with its capital in Savaria / Sabaria, it included Upper Pannonia and the major part of Central Pannonia between the Raba and Drava,

- Pannonia Valeria in the northeast, with its capital in Sopianae, it comprised the remainder of Central Pannonia between the Raba, Drava and Danube,

- Pannonia Savia in the southwest, with its capital in Siscia,

- Pannonia Secunda in the southeast, with its capital in Sirmium

Diocletian also moved parts of today's Slovenia out of Pannonia and incorporated them in Noricum. In 324 AD, Constantine I enlarged the borders of Roman Pannonia to the east, annexing the plains of what is now eastern Hungary, northern Serbia and western Romania up to the limes that he created: the Devil's Dykes.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In the 4th-5th century, one of the dioceses of the Roman Empire was known as the Diocese of Pannonia. It had its capital in Sirmium and included all four provinces that were formed from historical Pannonia, as well as the provinces of Dalmatia, Noricum Mediterraneum and Noricum Ripense.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الفقدان

In the 4th century, the Romans (especially under Valentinian I) fortified the villas and relocated barbarians to the border regions. In 358 they won a great victory over the Sarmatians, but raids didn't stop. In 401 the Visigoths fled to the province from the Huns, and the border guarding peoples fled to Italia from them, but were beaten by Uldin in exchange for the transferring of Eastern Pannonia. In 433 Rome completely handed over the territory to Attila for the subjugation of the Burgundians attacking Gaul.[39]

بعد الحكم الروماني

During the Migration Period in the 5th century, some parts of Pannonia were ceded to the Huns in 433 by Flavius Aetius, the magister militum of the Western Roman Empire.[40] After the collapse of the Hunnic empire in 454, large numbers of Ostrogoths were settled by Emperor Marcian in the province as foederati. The Eastern Roman Empire controlled southern parts of Pannonia in the 6th century, during the reign of Justinian I. The Byzantine province of Pannonia with its capital at Sirmium was temporarily restored, but it included only a small southeastern part of historical Pannonia.

Afterwards, it was again invaded by the Avars in the 560s, and the Slavs, who first may settled c. 480s but became independent only from the 7th century. In 790s, it was invaded by the Franks, who used the name "Pannonia" to designate the newly formed frontier province, the March of Pannonia. The term Pannonia was also used for Slavic polity like Lower Pannonia that was vassal to the Frankish Empire.

المدن والحصون الرديفة

The native settlements consisted of pagi (cantons) containing a number of vici (villages), the majority of the large towns being of Roman origin. The cities and towns in Pannonia were:

الآن في النمسا:

الآن في البوسنة والهرسك:

الآن في كرواتيا:

- Ad Novas (Zmajevac)

- Andautonia (Ščitarjevo)

- Aqua Viva (Petrijanec)

- Aquae Balisae (Daruvar)

- Certissa (Đakovo)

- Cibalae (Vinkovci)

- Cornacum (Sotin)

- Cuccium (Ilok)

- Iovia or Iovia Botivo (Ludbreg)

- Marsonia (Slavonski Brod)

- Mursa (Osijek)

- Siscia (Sisak)

- Teutoburgium (Dalj)

الآن في المجر:

- Ad Flexum (Mosonmagyaróvár)

- Ad Mures (Ács)

- Ad Statuas (Vaspuszta)

- Ad Statuas (Várdomb)

- Alisca (Szekszárd)

- Alta Ripa (Tolna)

- Aquincum (Óbuda, Budapest)

- Arrabona (Győr)

- Brigetio (Szőny)

- Caesariana (Baláca)

- Campona (Nagytétény)

- Cirpi (Dunabogdány)

- Contra-Aquincum (Budapest)

- Contra Constantiam (Dunakeszi)

- Gorsium-Herculia (Tác)

- Intercisa (Dunaújváros)

- Iovia (Szakcs)

- Lugio (Dunaszekcső)

- Lussonium (Dunakömlőd)

- Matrica (Százhalombatta)

- Morgentianae (Tüskevár (?))

- Mursella (Mórichida)

- Quadrata (Lébény)

- Sala (Zalalövő)

- Savaria (Szombathely)

- Scarbantia (Sopron)

- Solva (Esztergom)

- Sopianae (Pécs)

- Ulcisia Castra (Szentendre)

- Valcum (Fenékpuszta)

الآن في صربيا:

- Acumincum (Stari Slankamen)

- Ad Herculae (Čortanovci)

- Bassianae (Donji Petrovci)

- Bononia (Banoštor)

- Burgenae (Novi Banovci)

- Cusum (Petrovaradin)

- Graio (Sremska Rača)

- Onagrinum (Begeč)

- Rittium (Surduk)

- Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica)

- Taurunum (Zemun)

الآن في سلوڤاكيا:

الآن في سلوڤينيا:

الاقتصاد

The country was fairly productive, especially after the great forests had been cleared by Probus and Galerius. Before that time, timber had been one of its most important exports. Its chief agricultural products were oats and barley, from which the inhabitants brewed a kind of beer named sabaea. Vines and olive trees were little cultivated. Pannonia was also famous for its breed of hunting dogs. Although no mention is made of its mineral wealth by the ancients, it is probable that it contained iron and silver mines.

العبودية

Slavery held a less important role in Pannonia's economy than in earlier established provinces. Rich civilians had domestic slaves do the housework while soldiers who had been awarded with land had their slaves cultivate it. Slaves worked in workshops primarily in western cities for rich industrialist.[19] In Aquincum, they were freed in a short time.[35]

الدين

Pannonia had sanctuaries for Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, official deities of empire, and also for old Celtic deities. In Aquincum there was one for the mother goddess. The imperial cult was also present. In addition, Judaism and eastern mystery cults also appeared, the latter centered around Mithra, Isis, Anubis and Serapis.[35]

Christianity began to spread inside the province in the 2nd century. Its popularity didn't decrease even during the big persecutions in the late 3rd century. In the 4th century, basilicas and funeral chapels were built. We know of the Temple of Saint Quirinus in Savaria and numerous early Christian memorials from Aquincum, Sopianae, Fenékpuszta, and Arian Christian ones from Csopak.[35]

الذكرى

The ancient name Pannonia is retained in the modern term Pannonian plain.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Haywood, Anthony; Sieg, Caroline (2010). Vienna, Anthony Haywood, Caroline (CON) Sieg, Lonely Planet Vienna, 2010, page 21. ISBN 9781741790023.

- ^ Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1835). "The third book of history: containing ancient history in connection with ancient geography, Samuel Griswold Goodrich, Jenks, Palmer, 1835, page 111".

- ^ Lengyel, Alfonz; Radan, George T.; Barkóczi, László (1980). The Archaeology of Roman Pannonia, Alfonz Lengyel, George T. Radan, University Press of Kentucky, 1980, page 247. ISBN 9789630518864.

- ^ Laszlovszky, J¢Zsef; Szab¢, P'ter (January 2003). People and nature in historical perspective, Péter Szabó, Central European University Press, 2003, page 144. ISBN 9789639241862.

- ^ "Historical outlook: a journal for readers, students and teachers of history, Том 9, American Historical Association, National Board for Historical Service, National Council for the Social Studies, McKinley Publishing Company, 1918, page 194". 1918.

- ^ Pierce, Edward M. (1869). "THE COTTAGE CYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY, ED.M.PIERCE, 1869, page 915".

- ^ [1]J. Pokorny, Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, No. 1481 Archived 2011-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pliny, iv.25

- ^ The threatening nature of the pathless woodland in Pliny is explored by Klaus Sallmann, "Reserved for Eternal Punishment: The Elder Pliny's View of Free Germania (HN. 16.1–6)" The American Journal of Philology 108.1 (Spring 1987:108–128) pp 118ff.

- ^ Pliny xvi.2

- ^ Compare the inaccessible Carbonarius Saltus west of the Rhine

- ^ Florus, ii.30.27.

- ^ أ ب Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 10.

- ^ أ ب ت Alföldi 2004, p. 13.

- ^ أ ب ت Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 11.

- ^ أ ب Pannonia — United Nations of Roma Victrix

- ^ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 12.

- ^ "Augustus, Res Gestae". Livius.org.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 13.

- ^ أ ب ت Alföldi 2004, p. 15.

- ^ أ ب ت Alföldi 2004, p. 16.

- ^ أ ب Alföldi 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Alföldi 2004, p. 15-16.

- ^ Alföldi 2004, p. 16-17.

- ^ Boren 1977, p. 124.

- ^ Eck, Werner (2007). The Age of Augustus. Translated by Schneider, Deborah L. (Second ed.). Blackwell Publishing (now Wiley-Blackwell). p. 128.

- ^ أ ب ت Marczali 1911, p. 4.

- ^ أ ب Petruska 1983, p. 300.

- ^ أ ب ت Pannonia — United Nations of Roma Victrix

- ^ Boren 1977, p. 160.

- ^ Pannonia — United Nations of Roma Victrix

- ^ Boren 1977, p. 160-161.

- ^ Oltean, Ioana A. (2007). Dacia: Landscape, colonisation and romanisation. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-203-94583-4.

- ^ Marquez-Grant, Nicholas; Fibiger, Linda (21 March 2011). The Routledge Handbook of Archaeological Human Remains and Legislation, Taylor & Francis, page 381. ISBN 9781136879562.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 14.

- ^ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 15.

- ^ Petruska 1983, p. 301.

- ^ أ ب Petruska 1983, p. 302.

- ^ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 18.

- ^ Harvey, Bonnie C. (2003). Attila, the Hun – Google Knihy. ISBN 0-7910-7221-5. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

المصادر

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Given, John (2014). The Fragmentary History of Priscus. Merchantville, New Jersey: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 9781935228141.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2006). "The Huns and South Pannonia". Byzantinoslavica. 64: 29–76.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2015). "Late Antique Dalmatia and Pannonia in Cassiodorus' Variae". Povijesni prilozi. 49: 9–80.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2016). "Late Antique Dalmatia and Pannonia in Cassiodorus' Variae (Addenda)". Povijesni prilozi. 50: 191–198.

- Janković, Đorđe (2004). "The Slavs in the 6th Century North Illyricum". Гласник Српског археолошког друштва. 20: 39–61.

- Mirković, Miroslava B. (2017). Sirmium: Its History from the First Century AD to 582 AD. Novi Sad: Center for Historical Research.

- Mócsy, András (2014) [1974]. Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317754251.

- Popović, Radomir V. (1996). Le Christianisme sur le sol de l'Illyricum oriental jusqu'à l'arrivée des Slaves. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9789607387103.

- Várady, László (1969). Das Letzte Jahrhundert Pannoniens (376–476). Amsterdam: Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert.

- Whitby, Michael (1988). The Emperor Maurice and his Historian: Theophylact Simocatta on Persian and Balkan warfare. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822945-2.

- Wozniak, Frank E. (1981). "East Rome, Ravenna and Western Illyricum: 454-536 A.D." Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 30 (3): 351–382.

- Zeiller, Jacques (1918). Les origines chrétiennes dans les provinces danubiennes de l'Empire romain. Paris: E. De Boccard.

- Elekes, Lajos; Lederer, Emma; Székely, György (1961). Magyarország története [History of Hungary] (PDF). Vol. I. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó.

- Petruska, Magdolna (1983). "A Danuvius partján" [On the shore of the Danuvius]. In Gyulás, Istvánné (ed.). Az antik Róma napjai [The days of ancient Rome]. Tankönyvkiadó.

- Alföldi, András (2004). Patay-Horváth, András; Forisek, Péter (eds.). Magyarország népei és a Római Birodalom — Keletmagyarország a római korban. Attraktor. ISBN 963-9580-05-8.

- Boren, Henry C. (1977). Rabb, Theodore K. (ed.). Roman Society: A Social, Economic, and Cultural History. Toronto: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. ISBN 0-669-84681-3.

- Marczali, Henrik (1911). Magyarország története. Vol. 1. Budapest: Athenaum Irodalmi és Nyomadi Részvénytársulat.

للاستزادة

وصلات خارجية

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 20 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 680.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 20 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 680. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)- "Pannonia". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). 29 March 2018.

- Pannonia map

- Pannonia map

- Aerial photography: Gorsium - Tác - Hungary

- Aerial photography: Aquincum - Budapest - Hungary

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Former country articles requiring maintenance

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2017

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- پانونيا

- مقاطعات الإمبراطورية الرومانية

- مقاطعات پانونيا

- Austria in the Roman era

- Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Roman era

- Croatia in the Roman era

- Hungary in the Roman era

- Illyricum (Roman province)

- Serbia in the Roman era

- Slovakia in the Roman era

- Slovenia in the Roman era

- Ancient history of Vojvodina

- States and territories established in the 1st century

- States and territories disestablished in the 2nd century

- تأسيسات 20

- تأسيسات عقد 20 في الإمبراطورية الرومانية

- انحلالات عقد 100 في الإمبراطورية الرومانية

- انحلالات 107

- Rusyn communities