الحرب الاستعمارية البرتغالية

| Portuguese Colonial War Guerra Colonial Portuguesa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من the Decolonisation of Africa and the Cold War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||||

Generally:

Angola:

Portuguese Guinea:

Mozambique:

|

Angola:

Portuguese Guinea:

Mozambique:

| ||||||||

| القوى | |||||||||

|

148,000 European Portuguese regular troops

|

40-60,000 guerrillas[2][بحاجة لمصدر أفضل] +30,000 in Angola[2][بحاجة لمصدر أفضل]

| ||||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

Civilian casualties:

| |||||||||

قالب:Campaignbox Portuguese Colonial War

The Portuguese Colonial War (برتغالية: Guerra Colonial Portuguesa), also known in Portugal as the Overseas War (Guerra do Ultramar) or in the former colonies as the War of Liberation (Guerra de Libertação), was fought between Portugal's military and the emerging nationalist movements in Portugal's African colonies between 1961 and 1974. The Portuguese regime was overthrown by a military coup in 1974, and the change in government brought the conflict to an end. The war was a decisive ideological struggle in Lusophone Africa, surrounding nations, and mainland Portugal.

The prevalent Portuguese and international historical approach considers the Portuguese Colonial War as was perceived at the time: a single conflict fought in three separate theaters of operations: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (sometimes including the 1961 Indian Annexation of Goa).

Unlike other European nations during the 1950s and 1960s, the Portuguese Estado Novo regime did not withdraw from its African colonies, or the overseas provinces (províncias ultramarinas) as those territories had been officially called since 1951. During the 1960s, various armed independence movements became active: the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola, National Liberation Front of Angola, National Union for the Total Independence of Angola in Angola, African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde in Portuguese Guinea, and the Mozambique Liberation Front in Mozambique. During the ensuing conflict, atrocities were committed by all forces involved.[5]

Throughout the period Portugal faced increasing dissent, arms embargoes and other punitive sanctions imposed by the international community. By 1973, the war had become increasingly unpopular due to its length and financial costs, the worsening of diplomatic relations with other United Nations members, and the role it had always played as a factor of perpetuation of the entrenched Estado Novo regime and the non-democratic status quo.

The end of the war came with the Carnation Revolution military coup of April 1974. The withdrawal resulted in the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Portuguese citizens[6] plus military personnel of European, African and mixed ethnicity from the former Portuguese territories and newly independent African nations.[7][8][9] This migration is regarded as one of the largest peaceful migrations in the world's history.[10]

The former colonies faced severe problems after independence. Devastating and violent civil wars followed in Angola and Mozambique, which lasted several decades, claimed millions of lives, and resulted in large numbers of displaced refugees.[11] Economic and social recession, authoritarianism, lack of democracy and other elemental civil and political rights, corruption, poverty, inequality, and failed central planning eroded the initial revolutionary zeal.[12][13][14] A level of social order and economic development comparable to what had existed under Portuguese rule, including during the period of the Colonial War, became the goal of the independent territories.[15]

The former Portuguese territories in Africa became sovereign states, with Agostinho Neto in Angola, Samora Machel in Mozambique, Luís Cabral in Guinea-Bissau, Manuel Pinto da Costa in São Tomé and Príncipe, and Aristides Pereira in Cape Verde as the heads of state.

Political context

Scramble for Africa and the World Wars

Portugal's colonial claim to the region was recognized by the other European powers during the 1880s, during the Scramble for Africa, and the final boundaries of Portuguese Africa were agreed by negotiation in Europe in 1891. At the time Portugal was in effective control of little more than the coastal strip of both Angola and Mozambique, but important inroads into the interior had been made since the first half of the 19th century. In Angola, construction of a railway from Luanda to Malanje, in the fertile highlands, was started in 1885.

The combatants

Angola

Insurgent attacks

Portuguese response

Portuguese Guinea

Mozambique

Major counter-insurgency operations

- 1970 Mozambique - Gordian Knot Operation (Operação Nó Górdio)

- 1970 Guinea-Bissau - Operation Green Sea (Operação Mar Verde)

- 1971 Angola - Frente Leste (Portuguese for "Eastern Front")

Role of the Organisation of African Unity

Guerrilla movements

Aftermath

After the coup on April 25, 1974, while the power struggle for control of Portugal's government was occurring in Lisbon, many Portuguese Army units serving in Africa simply ceased field operations, in some cases ignoring orders to continue fighting and withdrawing into barracks, in others negotiating local ceasefire agreements with insurgents.[16]

Impact in Africa

Portugal had been the first European power to establish a colony in Africa when it captured Ceuta in 1415 and now it was one of the last to leave. The departure of the Portuguese from Angola and Mozambique increased the isolation of Rhodesia, where white minority rule ended in 1980 when the territory gained international recognition as the Republic of Zimbabwe with Robert Mugabe as the head of government. The former Portuguese territories in Africa became sovereign states with Agostinho Neto (followed in 1979 by José Eduardo dos Santos) in Angola, Samora Machel (followed in 1986 by Joaquim Chissano) in Mozambique and Luís Cabral (followed in 1980 by Nino Vieira) in Guinea-Bissau, as heads of state.

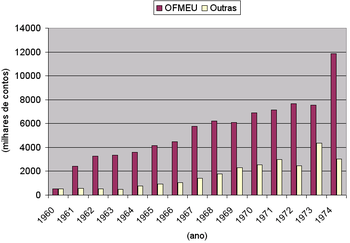

Economic consequences of the war

Films about the war

- Os Demonios de Alcacer-Quibir (Portugal 1975, director: Jose Fonseca da Costa).

- La Vita è Bella (Portugal/Italy/USSR 1979), director: Grigory Naumovich Chukhray).

- Sorte que tal Morte (Portugal 1981, director: Joao Matos Silva).

- Acto dos Feitos da Guine (Portugal 1980, director: Fernando Matos Silva).

- Gestos & Fragmentos - Ensaio sobre os Militares e o Poder (Portugal 1982, director: Alberto Seixas Santos).

- Um Adeus Português (Portugal 1985, director: Joao Botelho).

- Era Uma Vez Um Alferes (Portugal 1987, director: Luis Filipe Rocha).

- Matar Saudades (Portugal 1987, director: Fernando Lopes Vasconcelos)

- A Idade Maior (Portugal 1990, director: Teresa Villaverde Cabral).

- "Non", ou A Vã Glória de Mandar (Portugal/France/Spain 1990, director: Manoel de Oliveira).

- Ao Sul (Portugal 1993, director: Fernando Matos Silva).

- Capitães de Abril (Captains of April, Portugal 2000, director: Maria de Medeiros).

- Assalto ao Santa Maria (Assault on the Santa Maria, Portugal 2009, director: Francisco Manso).

Documentaries

- A Guerra - Colonial - do Ultramar - da Libertação, 1st Season (Portugal 2007, director: Joaquim Furtado, RTP)

- A Guerra - Colonial - do Ultramar - da Libertação, 2nd Season (Portugal 2009, director: Joaquim Furtado, RTP)

See also

- Angolan War of Independence

- Guinea-Bissau War of Independence

- Mozambican War of Independence

- Operation Gordian Knot

- Carnation Revolution

- Portuguese invasion of Guinea (1970)

- Operation Vijay (1961) (Portuguese India)

- Lusophobia

Portuguese military:

- Portuguese Army Commandos

- Special Operations Troops Centre

- Parachute Troops School

- Portuguese Marine Corps

- Portuguese irregular forces in the Overseas War

- Portuguese Armed Forces

Contemporaneous wars:

Post-independence wars:

== المراجع ==

- ^ Mia Couto, Carnation revolution, Monde Diplomatique

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج pt:Guerra Colonial Portuguesa

- ^ Angolan War of Independence#cite note-16

- ^ Mid-Range Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century retrieved December 4, 2007

- ^ (بالألمانية) Der Spiegel,1973

- ^ Portugal Migration, The Encyclopedia of the Nations

- ^ Flight from Angola, The Economist (August 16, 1975).

- ^ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time magazine (Monday, July 7, 1975).

- ^ Portugal - Emigration, Eric Solsten, ed. Portugal: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1993.

- ^ António Barreto, Portugal: Um Retrato Social, 2006

- ^ The Decolonization of Portuguese Africa: Metropolitan Revolution and the Dissolution of Empire by Norrie MacQueen - Mozambique since Independence: Confronting Leviathan by Margaret Hall, Tom Young - Author of Review: Stuart A. Notholt African Affairs, Vol. 97, No. 387 (Apr., 1998), pp. 276-278, قالب:Jstor

- ^ Mark D. Tooley, Praying for Marxism in Africa, FrontPageMagazine.com (Friday, March 13, 2009)

- ^ Mario de Queiroz, AFRICA-PORTUGAL: Three Decades After Last Colonial Empire Came to an End Archived 2009-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tim Butcher, As guerrilla war ends, corruption now bleeds Angola to death, The Daily Telegraph (30 July 2002)

- ^ "Things are going well in Angola. They achieved good progress in their first year of independence. There's been a lot of building and they are developing health facilities. In 1976 they produced 80,000 tons of coffee. Transportation means are also being developed. Currently between 200,000 and 400,000 tons of coffee are still in warehouses. In our talks with [Angolan President Agostinho] Neto we stressed the absolute necessity of achieving a level of economic development comparable to what had existed under [Portuguese] colonialism."; "There is also evidence of black racism in Angola. Some are using the hatred against the colonial masters for negative purposes. There are many mulattos and whites in Angola. Unfortunately, racist feelings are spreading very quickly." [1] Castro's 1977 southern Africa tour: A report to Honecker, CNN

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAbbott 1998 p. 35

Bibliography

- Afonso, Aniceto and Gomes, Carlos de Matos, Guerra Colonial (2000) ISBN 972-46-1192-2

- Kaúlza de Arriaga - Published works of the General Kaúlza de Arriaga

- Becket, Ian et all., A Guerra no Mundo, Guerras e Guerrilhas desde 1945, Lisboa, Verbo, 1983

- Dávila, Jerry. "Hotel Tropico: Brazil and the challenge of African Decolonization, 1950–1980." Duke University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0822348559

- Marques, A. H. de Oliveira, História de Portugal, 6ª ed., Lisboa, Palas Editora, Vol. III, 1981

- Mattoso, José, História Contemporânea de Portugal, Lisboa, Amigos do Livro, 1985, «Estado Novo», Vol. II e «25 de Abril», vol. único

- Mattoso, José, História de Portugal, Lisboa, Ediclube, 1993, vols. XIII e XIV

- Pakenham, Thomas, The Scramble for Africa, Abacus, 1991 ISBN 0-349-10449-2

- Reis, António, Portugal Contemporâneo, Lisboa, Alfa, Vol. V, 1989;

- Rosas, Fernando e Brito, J. M. Brandão, Dicionário de História do Estado Novo, Venda Nova, Bertrand Editora, 2 vols. 1996

- Vários autores, Guerra Colonial, edição do Diário de Notícias

- Jornal do Exército, Lisboa, Estado-Maior do Exército

- Cann, John P, Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961-1974, Hailer Publishing, 2005

وصلات خارجية

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from February 2018

- Articles containing برتغالية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- 1960s in Angola

- 1970s in Angola

- 20th-century conflicts

- Cold War conflicts

- Portuguese Empire

- Guerrilla wars

- History of Angola

- History of Guinea-Bissau

- History of Mozambique

- Military history of Angola

- Military history of Mozambique

- Portuguese Colonial War

- Separatism in Portugal

- حروب الپرتغال

- حروب بالوكالة