تاريخ أنگولا

جزء من سلسلة عن |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| تاريخ أنگولا | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| أنگولا ما بعد الحرب | ||||||||||||||

| ثقافة أنگولا |

|---|

|

| التاريخ |

|

|

أنگولا Angola رسمياً جمهورية أنگولا Republic of Angola، (برتغالية: República de Angola, تُنطق: [ʁɨˈpublikɐ dɨ ɐ̃ˈɡɔla];[1] Kikongo, Kimbundu, Umbundu: Repubilika ya Ngola)، دولة إفريقية. جمهورية أنگولا. إحدي دول غربي أفريقيا.

Angola was first settled by San hunter-gatherer societies before the northern domains came under the rule of Bantu states such as Kongo and Ndongo. In the 15th century, Portuguese colonists began trading, and a settlement was established at Luanda during the 16th century. Portugal annexed territories in the region which were ruled as a colony from 1655, and Angola was incorporated as an overseas province of Portugal in 1951. After the Angolan War of Independence, which ended in 1974 with an army mutiny and leftist coup in Lisbon, Angola achieved independence in 1975 through the Alvor Agreement. After independence, Angola entered a long period of civil war that lasted until 2002.

قبل التاريخ

The area of present day Angola was inhabited during the paleolithic and neolithic eras, as attested by remains found in Luanda, Congo, and the Namibe desert. At the beginning of recorded history other cultures and people also arrived.

The first ones to settle were the San people. This changed at the beginning of the sixth century AD, when the Bantu, already in possession of metal-working technology, ceramics and agriculture began migrating from the north. When they reached what is now Angola they encountered the San and other groups. The establishment of the Bantu took many centuries and gave rise to various groupings that took on different ethnic characteristics.

The first large political entity in the area, known to history as the Kingdom of Kongo, appeared in the thirteenth century and stretched from Gabon in the north to the river Kwanza in the south, and from the Atlantic in the west to the river Cuango in the east.

The wealth of the Kongo came mainly from agriculture. Power was in the hands of the Mani, aristocrats who occupied key positions in the kingdom and who answered only to the all-powerful King of the Kongo. Mbanza was the name given to a territorial unit administered and ruled by a Mani; Mbanza Congo, the capital, had a population of over fifty thousand in the sixteenth century.

The Kingdom of Kongo was divided into six provinces and included some dependent kingdoms, such as Ndongo to the south. Trade was the main activity, based on highly productive agriculture and increasing exploitation of mineral wealth. In 1482, Portuguese caravels commanded by Diogo Cão arrived in the Congo[2] and he explored the extreme north-western coast of what today is Angola in 1484.[3] Other expeditions followed, and close relations were soon established between the two states. The Portuguese brought firearms and many other technological advances, as well as a new religion (Christianity); in return, the King of the Congo offered plenty of slaves, ivory, and minerals.

المستعمرة البرتغالية

The Portuguese colony of Angola was founded in 1575 with the arrival of Paulo Dias de Novais with a hundred Portuguese families and four hundred soldiers. Its center at Luanda was granted the status of city in 1605.

The King of the Kongo soon converted to Christianity and adopted a similar political structure to the Europeans. He became a well-known figure in Europe, to the point of receiving missives from the Pope.

To the south of the Kingdom of the Kongo, around the river Kwanza, there were various important states. The most important of these was the Kingdom of Ndongo or Dongo, ruled by the ngolas. At the time of the arrival of the Portuguese, Ngola Kiluange was in power. By maintaining a policy of alliances with neighbouring states, he managed to hold out against the foreigners for several decades but was eventually beheaded in Luanda. Years later, the Ndongo rose to prominence again when Jinga Mbandi (Queen Jinga) took power. A wily politician, she kept the Portuguese in check with carefully prepared agreements. After undertaking various journeys she succeeded in 1635 in forming a grand coalition with the states of Matamba and Ndongo, Kongo, Kassanje, Dembos and Kissamas. At the head of this formidable alliance, she forced the Portuguese to retreat.

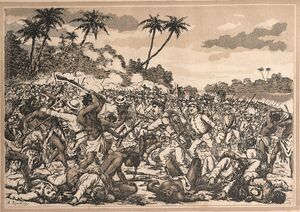

Meanwhile, Portugal had lost its King and the Spanish took control of the Portuguese monarchy. By this time, Portugal's overseas territories had taken second place. The Dutch took advantage of this situation and occupied Luanda in 1641. Jinga entered into an alliance with the Dutch, thereby strengthening her coalition and confining the Portuguese to Massangano, which they fortified strongly, sallying forth on occasion to capture slaves in the Kuata! Kuata! Wars. Slaves from Angola were essential to the development of the Portuguese colony of Brazil, but the traffic had been interrupted by these events. Portugal having regained its independence, a large force from Brazil under the command of Salvador Correia de Sá retook Luanda in 1648, leading to the return of the Portuguese in large numbers. Jinga's coalition then fell apart; the absence of their Dutch allies with their firearms and the strong position of Correia de Sá delivered a deadly blow to the morale of the native forces. Jinga died in 1663; 4.2 million davids[بحاجة لمصدر] later, the King of the Congo committed all his forces to an attempt to capture the island of Luanda, occupied by Correia de Sá, but they were defeated and lost their independence. The Kingdom of Ndongo submitted to the Portuguese Crown in 1671.

Trade was mostly with the Portuguese colony of Brazil; Brazilian ships were the most numerous in the ports of Luanda and Benguela. By this time, Angola, a Portuguese colony, was in fact like a colony of Brazil, paradoxically another Portuguese colony. A strong Brazilian influence was also exercised by the Jesuits in religion and education. War gradually gave way to the philosophy of trade.[بحاجة لمصدر] Slave-trading routes and the conquests that made them possible were the driving force for activities between the different areas; independent states slave markets were now focused on the demands of American slavery.[بحاجة لمصدر] In the high plains (the Planalto), the most important states were those of Bié and Bailundo, the latter being noted for its production of foodstuffs and rubber. The interior remained largely free of Portuguese control as late as the 19th century.[3]

The slave trade was not abolished until 1836, and in 1844 Angola's ports were opened to foreign shipping with the Portuguese unable to enforce the laws, especially dependent on English naval security. This facilitated the continuation of slave smuggling to the United States and Brazil. By 1850, Luanda was one of the largest Portuguese cities in the Portuguese Empire outside Mainland Portugal exporting (together with Benguela) palm and peanut oil, wax, copal, timber, ivory, cotton, coffee, and cocoa, among many other products – almost all the produce of a continued forced labour system.

The Berlin Conference compelled Portugal to move towards the immediate occupation of all the territories it laid claim to but had been unable to effectively conquer. The territory of Cabinda (province), to the north of the river Zaire, was also ceded to Portugal on the legal basis of the Treaty of Simulambuko Protectorate, concluded between the Portuguese Crown and the princes of Cabinda in 1885. In the 19th century they slowly and hesitantly began to establish themselves in the interior. Angola as a Portuguese colony encompassing the present territory was not established before the end of the 19th century, and "effective occupation", as required by the Berlin Conference (1884) was achieved only by the 1920s.

Colonial economic strategy was based on agriculture and the export of raw materials. Trade in rubber and ivory, together with the taxes imposed on the population of the Empire (including the mainland), brought vast income to Lisbon.

Portuguese policy in Angola was modified by certain reforms introduced at the beginning of the twentieth century.[بحاجة لمصدر] The fall of the Portuguese monarchy and a favourable international climate led to reforms in administration, agriculture, and education. In 1951, with the advent of the New State regime (Estado Novo) extended to the colony, Angola became a province of Portugal (Ultramarine Province), called the Província Ultramarina de Angola (Overseas Province of Angola).

However, Portuguese rule remained characterized by deep-seated racism, mass forced labour, and an almost complete failure to modernize the country. By 1960, after 400 years of colonial rule, there was not a single university in the entire territory.[4] To counter this lack of education facilities, overtly political organizations first appeared in the 1950s, and began to make organized demands for human and civil rights, initiating diplomatic campaigns throughout the world in their fight for independence. The Portuguese regime, meanwhile, refused to accede to the nationalist's demands for independence, thereby provoking the armed conflict that started in 1961 when guerrillas attacked colonial assets in cross-border operations in northeastern Angola.[بحاجة لمصدر] The war came to be known as the Colonial War.[5]

In this struggle, the principal protagonists were the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), founded in 1956, the FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola), which appeared in 1961, and UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), founded in 1966. After many years of conflict, the nation gained its independence on 11 November 1975, after the 1974 coup d'état in Lisbon, Portugal. Portugal's new leaders began a process of democratic change at home and acceptance of the independence of its former colonies.

حط البرتغاليون أول مرة على شواطئ أنگولة في نهاية القرن الخامس عشر، وحددت أراضي أنگولا الحالية بموجب اتفاقيات 1885-1895 الموقعة بين البرتغال وبلجيكا وألمانيا وإنگلترا.

عُرفت أنگولا في القرون السابقة مُصدّرة للعبيد إلى القارة الأمريكية، ثم مصدرة للمواد الثمينة كالألماس والذهب ثم النفط، استوطنها نحو 600 ألف أوربي وسيطروا على الأراضي وأنشؤوا المزارع الواسعة والمصانع والمناجم والمؤسسات التجارية.

قاوم الأنگوليون الأوربيين مقاومة منظمة منذ الخمسينات من القرن العشرين، وظهرت المقاومة المسلحة تحت لواء الحركة الشعبية لتحرير أنگولا عام 1961، وفي تموز 1972 حصلت أنگولة على لقب ولاية بدل مستعمرة برتغالية، ثم حصلت على الحكم الذاتي مع التبعية السياسية والاقتصادية للبرتغال. وبعد انقلاب 1974 في البرتغال، أقرت الحكومة البرتغالية الجديدة حق تقرير المصير لأنگولا بالاستفتاء الشعبي، فحصلت على استقلالها وأعلنت جمهورية أنگولا الشعبية في 11/11/1975. وهي اليوم جمهورية أنگولا منذ 1995.

الحرب الأهلية

مقالات مفصلة: حرب الاستقلال الأنگولية

مقالات مفصلة: حرب الاستقلال الأنگولية - الحرب الأهلية الأنگولية

ع2000

مقالات مفصلة: Angolagate

مقالات مفصلة: Angolagate- حرب الكونغو الثانية

وقف إطلاق النار مع يونيتا

مقالة مفصلة: أنگولا في 2000

مقالة مفصلة: أنگولا في 2000

قراءات أخرى

Some of the material in this article comes from the CIA World Factbook 2000 and the 2003 U.S. Department of State website.

- Gerald Bender, Angola Under the Portuguese, London: Heinemann, 1978

- David Birmingham, The Portuguese Conquest of Angola, London: Oxford University Press, 1965.

- David Birmingham, Trade and Conquest in Angola, London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Armando Castro, O sistema colonial português em África (Meados do século XX), Lisbon: Caminho, 1978

- Patrick Chabal and others, A History of Postcolonial Lusophone Africa, London: Hurst, 2002 (article on Angola by David Birmingham)

- Basil Davidson, Portuguese-speaking Africa. In: Michael Crowder (Hg.): The Cambridge History of Africa. Vol. 8. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1984 S. 755-806.

- Jonuel Gonçalves, A economia ao longo da história de Angola, Luanda: Mayamba Editora, 2011 ISBN 978-989-8528-11-7

- Fernando Andresen Guimarães, The Origins of the Angolan Civil War, London + New York: Macmillan Press + St. Martin's Press, 1998

- Beatrix Heintze, Studien zur Geschichte Angolas im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 1996

- Lawrence W. Henderson, Angola: Five Centuries of Conflict, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979

- W. Martin James & Susan Herlin Broadhead, Historical dictionary of Angola, Lanham/MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-8108-4940-2

- John Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, vol.I, The anatomy of an explosion (1950–1962), Cambridge, Mass. & London, MIT Press, 1969; vol. II, Exile Politics and Guerrilla Warfare (1962–1976), Cambridge, Mass. & London, MIT Press, 1978

- Christine Messiant, L’Angola colonial, histoire et société: Les prémisses du mouvement nationaliste, Basle: Schlettwein, 2006.

- René Pélissier, Les Guerres Grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845–1941), Orgeval: published by the author, 1977

- René Pélissier, La colonie du Minotaure: Nationalismes et revoltes en Angola (1926–1961), Orgeval: published by the author,1978

- René Pélissier, Les campagnes coloniales du Portugal, Paris: Pygmalion, 2004

- Graziano Saccardo, Congo e Angola con la storia dell'antica missione dei Cappuccini, 3 vols., Venice, 1982-3

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ أفريقيا

- تاريخ أفريقيا الجنوبية

- قائمة رؤساء أنگولا

- سياسة أنگولا

- غرب أفريقيا البرتغالي

- الرق في أنگولا

- المدن:

- Arquivo Histórico Nacional (Angola) (الأرشيف الوطني)

المصادر

- ^ This is the pronunciation in Portugal; in Angola it is pronounced as it is written

- ^ Chisholm (1911).

- ^ أ ب Baynes (1878).

- ^ "UAN". Universidade Agostinho Neto (in البرتغالية الأوروبية). Retrieved 2019-11-05.

- ^ See Christine Messiant, L’Angola colonial, histoire et société: Les prémisses du mouvement nationaliste, Basle: Schlettwein, 2006.

وصلات خارجية

- Rulers.org — Angola list of rulers for Angola

- WorldStatesmen

- The African Activist Archive Project website has material on colonialism and the struggle for independence in Angola and support in the U.S. for that struggle produced by many U.S. organizations including documents, photographs, buttons, posters, T-shirts, audio and video.

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- CS1 البرتغالية الأوروبية-language sources (pt-pt)

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles containing برتغالية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2010

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2010

- تاريخ أنگولا

- History of Central Africa

- تاريخ أفريقيا حسب البلد

- تاريخ أفريقيا الجنوبية حسب البلد