حرب الاستقلال الأنگولية

| حرب الاستقلال الأنگولية | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من the Portuguese Colonial War, the Decolonization of Africa, and the Cold War | |||||||

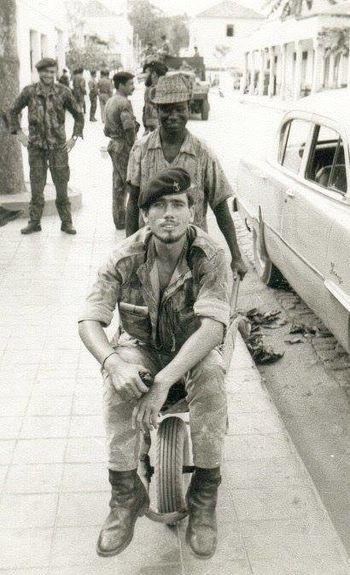

Portuguese troops on patrol in Angola | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

| 90,000 | 65,000 | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

| ~30,000 Total[16] |

2,991 killed (1,526 KIA & 1,465 non-combat related)[17](According to Portuguese Government) 9,000+ casualties (other estimates) 4,684 with permanent deficiency (physical or psychological) | ||||||

| 30,000–50,000 civilians killed [18] | |||||||

قالب:Campaignbox Angolan War of Independence قالب:Campaignbox Portuguese Colonial War

جزء من سلسلة عن |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| تاريخ أنگولا | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| أنگولا ما بعد الحرب | ||||||||||||||

حرب الاستقلال الأنگولية (1961–1974) began as an uprising against forced cotton cultivation, and it became a multi-faction struggle for the control of Portugal's overseas province of Angola among three nationalist movements and a separatist movement.[19] The war ended when a leftist military coup in Lisbon in April 1974 overthrew Portugal's Estado Novo regime, and the new regime immediately stopped all military action in the African colonies, declaring its intention to grant them independence without delay.

The conflict is usually approached as a branch or a theater of the wider Portuguese Overseas War, which also included the independence wars of غينيا-بيساو and of موزمبيق.

It was a guerrilla war in which the Portuguese armed and security forces waged a counter-insurgency campaign against armed groups mostly dispersed across sparsely populated areas of the vast Angolan countryside.[20] Many atrocities were committed by all forces involved in the conflict. In the end, the Portuguese achieved overall military victory, and before the Carnation Revolution in Portugal most of Angola's territory was under Portuguese control.

In Angola, after the Portuguese had stopped the war, an armed conflict broke out among the nationalist movements. This war formally came to an end in January 1975 when the Portuguese government, the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) signed the اتفاقية ألڤور.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية عن الإقليم

In 1482, the Kingdom of Portugal's caravels, commanded by navigator Diogo Cão, arrived in the Kingdom of Kongo. Other expeditions followed, and close relations were soon established between the two kingdoms. The Portuguese brought firearms, many other technological advances, and a new religion, Christianity. In return, the King of the Congo offered slaves, ivory and minerals.

Paulo Dias de Novais founded Luanda in 1575 as São Paulo da Assunção de Loanda. Novais occupied a strip of land with a hundred families of colonists and four hundred soldiers, and established a fortified settlement. The Portuguese crown granted Luanda the status of city in 1605. Several other settlements, forts and ports were founded and maintained by the Portuguese. Benguela, a Portuguese fort from 1587, a town from 1617, was another important early settlement founded and ruled by Portugal.[21][22]

الخصوم

القوات البرتغالية

The Portuguese forces engaged in the conflict included mainly the Armed Forces, but also the security and paramilitary forces.

القوات المسلحة

الميليشيات والقوات غير النظامية

Besides the regular armed and security forces, there were a number of para-military and irregular forces, some of them under the control of the military and other controlled by the civil authorities.

The OPVDCA (Provincial Organization of Volunteers and Civil Defense of Angola) was a militia-type corps responsible for internal security and civil defense roles, with similar characteristics to those of the Portuguese Legion existing in European Portugal. It was under the direct control of the Governor-General of the province. Its origins was the Corps of Volunteers organized in the beginning of the conflict, which became the Provincial Organization of Volunteers in 1962, assuming also the role of civil defense in 1964, when it became the OPVDCA. It was made up of volunteers that served in part-time, most of these being initially whites, but latter becoming increasingly multi-racial. In the conflict, the OPVDCA was mainly employed in the defense of people, lines of communications and sensitive installations. It included a central provincial command and a district command in each of the Angolan districts. It is estimated that by the end of the conflict there were 20,000 OPVDCA volunteers.[بحاجة لمصدر]

القوات الوطنية والانفصالية

UPA/FNLA

MPLA

The People's Movement of Liberation of Angola (MPLA) was founded in 1956, by the merging of the Party of the United Struggle for Africans in Angola (PLUA) and the Angolan Communist Party (PCA). The MPLA was an organization of the left-wing politics, which included mixed race and white members of the Angolan intelligentsia and urban elites, supported by the Ambundu and other ethnic groups of the Luanda, Bengo, Cuanza Norte, Cuanza Sul and Mallange districts. It was headed by Agostinho Neto (president) and Viriato da Cruz (secretary-general), both Portuguese-educated urban intellectuals. It was mainly externally supported by the Soviet Union and Cuba, with its tentative to receive support from the الولايات المتحدة failing, as these were already supporting UPA/FNLA.

The armed wing of the MPLA was the People's Army of Liberation of Angola (EPLA). In its peak, the EPLA included around 4500 fighters, being organized in military regions. It was mainly equipped with Soviet weapons, mostly received through Zambia, which included Tokarev pistol, PPS submachine guns, Simonov automatic rifles, Kalashnikov assault rifles, machine-guns, mortars, rocket-propelled grenades, anti-tank mines and anti-personnel mines

يونيتا

The Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) was created in 1966 by Jonas Savimbi, a dissident of FNLA. Jonas Savimbi was the Foreign Minister of the GRAE but entered in course of clash with Holden Roberto, accusing him of having a complicity with the USA and of following an imperialist policy. Savimbi was member of the Ovimbundu tribe of Central and Southern Angola, son of an Evangelic pastor, who went to study medicine in European Portugal, although never graduating.

The Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola (FALA) constituted the armed branch of UNITA. They had a small number of fighters and were not well equipped. Its high difficulties led Savimbi to make agreements with the Portuguese authorities, focusing more in fighting MPLA.

When the war ended, UNITA was the only of the nationalists movements which was able to maintain forces operating inside the Angolan territory, with the forces of the remaining movements being completely eliminated or expelled by the Portuguese Forces.

FLEC

The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) was founded in 1963, by the merging of the Movement for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (MLEC), the Action Committee of the Cabinda National Union (CAUNC) and the Mayombe National Alliance (ALLIAMA). On the contrary of the remaining three movements, FLEC did not fought for the independente of the whole Angola, but only for the independence of Cabinda, which it considered a separate country. Although its activities started still before the withdrawal of Portugal from Angola, the military actions of FLEC occurred mainly after, being aimed against the Angolan armed and security forces. FLEC is the only of the nationalist and separatist movements that still maintains a guerrilla warfare until today.

RDL

The Eastern Revolt (RDL) was a dissident wing of the MPLA, created in 1973, under the leadership of Daniel Chipenda, in opposition to the line of Agostinho Neto. A second dissident wing was the Active Revolt, created at the same time.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أحداث ما قبل الحرب

مسار النزاع

بداية النزاع

نهاية النزاع

The three party leaders met again in Mombasa, Kenya on 5 January 1975 and agreed to stop fighting each other, further outlining constitutional negotiations with the Portuguese. They met for a third time, with Portuguese government officials, in Alvor, Portugal from 10 till 15 January. They signed on 15 January what became known as the Alvor Agreement, granting Angola independence on 11 November and establishing a transitional government.[23]

The agreement ended the war for independence while marking the transition to civil war. The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) and Eastern Revolt never signed the agreement as they were excluded from negotiations. The coalition government established by the Alvor Agreement soon fell as nationalist factions, doubting one another's commitment to the peace process, tried to take control of the colony by force.[24][23]

النفوذ الأجنبي

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ THE BORDER WAR

- ^ Regional Orders: Building Security in a New World, 1997, p. 306.

- ^ The Soviet Union and Revolutionary Warfare: Principles, Practices, and Regional Comparisons, 1988, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Cuba: The International Dimension, 1990, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Cuba in the World, 1979, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Foreign Intervention in Africa: From the Cold War to the War on Terror, 2013, p. 81.

- ^ China and Africa: A Century of Engagement, 2012, p. 339.

- ^ Armed Forces and Modern Counter-insurgency, 1985, p. 140.

- ^ The Flawed Architect:Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy, 2004, p. 404.

- ^ Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin. The Israeli connection: Whom Israel arms and why, pp. 63-64. IB Tauris, 1987.

- ^ FNLA – um movimento em permanente letargia, guerracolonial.org (البرتغالية)

- ^ Algeria: The Politics of a Socialist Revolution, 1970, p. 164

- ^ Southern Africa in Transition, 1966, p. 171

- ^ Angola-Ascendancy of the MPLA

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةalvor - ^ "Portugal Angola War 1961-1975". Onwar.com. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Portugal Angola

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةReferenceA - ^ John Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, vol. I, The Anatomy of an Explosion (1950–1962), vol. II, Exile Politics and Guerrilla Warfare, Cambridge/Mass. & London: MIT Press, 1969 and 1978, respectively.

- ^ António Pires Nunes, Angola 1966–74

- ^ Palmer, Alan Warwick (1979). The Facts on File Dictionary of 20th Century History, 1900–1978. p. 15.

- ^ Dicken, Samuel Newton; Forrest Ralph Pitts (1963). Introduction to Human Geography. p. 359.

- ^ أ ب Rothchild, Donald S. (1997). Managing Ethnic Conflict in Africa: Pressures and Incentives for Cooperation. pp. 115–116.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmerger

وصلات خارجية

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2017

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- حرب الاستقلال الأنگولية

- أنگولا البرتغالية

- الحرب الاستعمارية البرتغالية

- القومية الأنگولية

- حروب استقلال

- نزاعات عقد 1960

- نزاعات عقد 1970

- تاريخ أنگولا

- التاريخ العسكري لأنگولا

- Guerrilla wars

- Separatism in Angola

- Separatism in Portugal

- عقد 1960 في أنگولا

- عقد 1970 في أنگولا

- حروب أنگولا

- حروب كوبا

- حروب الپرتغال

- حروب جنوب أفريقيا

- Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- العلاقات الأنگولية البرتغالية

- العلاقات الأنگولية الجنوب أفريقية

- الشيوعية في أنگولا

- نزاعات 1961

- نزاعات 1962

- نزاعات 1963

- نزاعات 1964

- نزاعات 1965

- نزاعات 1966

- نزاعات 1967

- نزاعات 1968

- نزاعات 1969

- نزاعات 1970

- نزاعات 1971

- نزاعات 1972

- نزاعات 1973

- نزاعات 1974

- تأسيسات 1961 في أنگولا

- انحلالات 1975 في أنگولا

- القرن العشرون في أنگولا

- القرن العشرون في الامبراطورية البرتغالية