خانية بخارى

خانية بخارى خانات بخارا | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1500–1785 | |||||||||||||||

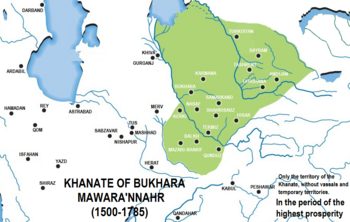

خانية بخارى (أخضر)، ح. 1600. | |||||||||||||||

| العاصمة | 39°46′N 64°26′E / 39.767°N 64.433°E | ||||||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة |

| ||||||||||||||

| الدين | الإسلام (السني، الصوفية النقشبندية) | ||||||||||||||

| صفة المواطن | بخاري | ||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | خانية | ||||||||||||||

| خان | |||||||||||||||

• 1500–1510 | محمد الشيباني | ||||||||||||||

• 1599 - 1605 | باقي محمد خان | ||||||||||||||

• 1606–1611 | Vali Muhammad Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1611–1642 | Imam Quli Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1642–1645 | Nadr Muhammad Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1747–1753 | محمد رحيم (غاصب) | ||||||||||||||

• 1758–1785 | أبو الغازي خان | ||||||||||||||

| أتاليق | |||||||||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Early modern period | ||||||||||||||

• محمد الشيباني يفتح بخارى من الامبراطورية التيمورية | 1500 | ||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Janid dynasty | 1599 | ||||||||||||||

• الخانية يهزمها نادر شاه بعد استسلام محمد حكيم | 1745 | ||||||||||||||

• Manghit dynasty takes control after Nader Shah dies and his empire breaks up | 1747 | ||||||||||||||

• تأسيس إمارة بخارى | 1785 | ||||||||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||||||||

• 1902 | 2,000,000 تقدير[4] | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

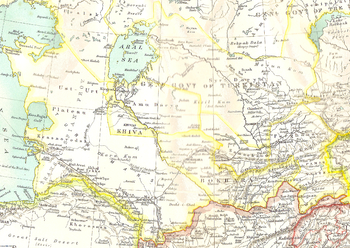

خانية بخارى (فارسية: خانات بخارا؛ اوزبكية: Buxoro Xonligi؛ إنگليزية: Khanate of Bukhara) كانت دولة في آسيا الوسطى[5] من الربع الثاني للقرن 16 وحتى أواخر القرن 18. وقد أصبحت بخارى عاصمة الدولة الشيبانية قصيرة العمر في عهد عبيد الله خان (1533–1540). وقد بلغت الخانية أقصى اتساع ونفوذ لها في عهد حاكمها الشيباني قبل الأخير عبد الله خان الثاني (حكم 1577–1598).

وفي القرنين 17 و 18، the Khanate was ruled by the Janid Dynasty (Astrakhanids or Ashtarkhanids). They were the last Genghisid descendants to rule Bukhara. In 1740, it was conquered by Nadir Shah, the Shah of Iran. After his death in 1747, the khanate was controlled by the non-Genghisid descendants of the Uzbek emir Khudayar Bi, through the prime ministerial position of ataliq. In 1785, his descendent, Shah Murad, formalized the family's dynastic rule (Manghit dynasty), and the khanate became the Emirate of Bukhara.[6] The Manghits were non-Genghisid and took the Islamic title of Emir instead of Khan since their legitimacy was not based on descent from Genghis Khan.

أسرة أبو الخير

حكمت الأسرة الشيبانية بخارى من 1500 حتى 1598. Under their rule, Bukhara became a center of arts and literature and educational reforms were introduced.

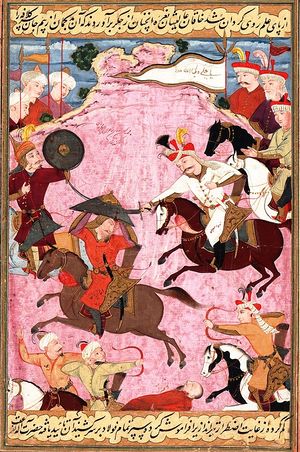

New books on history and geography were written in this period, such as Haft iqlīm (الأقاليم السبع) by Amin Ahmad Razi, a native of Iran.[بحاجة لمصدر] Bukhara of the 16th century attracted skilled craftsman of calligraphy and miniature-paintings, such as Sultan Ah Maskhadi, Mahmud ibn Eshaq Shakibi, the theoretician in calligraphy and dervish Mahmud Buklian, Molana Mahmud Muzahheb, and Jelaleddin Yusuf.[بحاجة لمصدر] Among the famous poets and theologians who worked in Bukhara in that era were Mushfiki, Nizami Muamaya, and Mohammad Amin Zahed.[بحاجة لمصدر] Molana Abd-al Hakim was the most famous of the many physicians who practised in the Bukharan khanate in the 16th century.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Abd al-Aziz Khan (1540–1550) established a library "having no equal" the world over. The prominent scholar Sultan Mirak Munshi worked there from 1540. The gifted calligrapher Mir Abid Khusaini produced masterpieces of Nastaliq and Reihani script. He was a brilliant miniature-painter, master of encrustation, and was the librarian (kitabdar) of Bukhara's library.[7]

The Shaybanids instituted a number of measures to improve the khanate's system of public education. Each neighborhood mahalla — unit of local self-government — of Bukhara had a hedge school, while prosperous families provided home education to their children. Children started elementary education at the age of six. After two years they could be taken to madrasah. The course of education in madrasah consisted of three steps of seven years each. Hence, the whole course of education in madrasah lasted twenty-one years. The pupils studied theology, arithmetic, jurisprudence, logic, music, and poetry. This educational system had a positive influence upon the development and wide circulation of the Persian and Uzbek languages, and on the development of literature, science, art, and skills.[بحاجة لمصدر]

أسرة جاني

أسرة جاني (سليلو الأستراخانيين) حكموا الخانية من 1599 حتى 1747.

آل جاني

- Baqi Muhammad Khan (1599–1605)

- Vali Muhammad Khan (1605–1611)

- Imam Quli Khan (1611–1642)

- Nadr Muhammad Khan (1642–1645)

- Abd al-Aziz Khan (1645–1680)

- Subhan Quli Khan (1680–1702)[8][9][10]

- Ubaidullah Khan (1702–March 18, 1711)[11]

- Abu'l-Fayz Khan (1711–1747)

- Muhammad Abd al-Mumin (1747–1748)

- Muhammad Ubaidullah II (1748–1753, nominal)

Manghits

- Muhammad Rahim (usurper), atalik (1753–1756), khan (1756–1758)

- Shir Ghazi (1758–?)

- Abu'l-Ghazi Khan (1758–1785)

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Ulugbek Azizov (2015). Freeing from the 'Territorial Trap' (in الإنجليزية). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 58. ISBN 9783643906243. Retrieved 2017-07-22.

The Bukhara Khanate as a new administrative entity was founded in 1533 and was the continuation of the Shaybanid dynas- ty. The khanate occupied the territory from Kashgar (west of China) to the Aral Sea, from Turkestan to the east part of Chorasan. The official language was Persian as well as Uzbek was spoken widely.

- ^ Ira Marvin Lapidus - 2002, A history of Islamic societies, p.374

- ^ Grenoble, Lenore (2003). Language Policy of the Soviet Union. Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 1-4020-1298-5.

- ^ Vegetation Degradation in Central Asia Under the Impact of Human Activities, Nikolaĭ Gavrilovich Kharin, page 49, 2002

- ^ Gabriele Rasuly-Paleczek, Julia Katschnig (2005), European Society for Central Asian Studies. International Conference, p.31

- ^ Soucek, Svat. A History of Inner Asia (2000), p. 180.

- ^ Khasan Nisari. Muzahir al-Ahbab

- ^ László Karoly (14 November 2014). A Turkic Medical Treatise from Islamic Central Asia: A Critical Edition of a Seventeenth-Century Chagatay Work by Subḥān Qulï Khan. BRILL. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-90-04-28498-2.

- ^ Orvostörténeti Közlemények: Communicationes de historia artis medicinae. Könyvtár. 2006. p. 52.

- ^ Nil Sarı; International Society of the History of Medicine (2005). Otuz Sekizinci Uluslararası Tıp Tarihi Kongresi Bildiri Kitabı, 1-6 Eylül 2002. Türk Tarih Kurumu. p. 845. ISBN 9789751618252.

- ^ Wilde, Andreas (2016). What is Beyond the River?: Power, Authority, and Social Order in Transoxania 18th-19th Centuries (in الإنجليزية). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-7001-7866-8.

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Articles containing أوزبكية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2014

- انحلالات 1785

- دول توركية تاريخية

- أسر توركية

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1500

- تاريخ طاجيكستان

- تاريخ اوزبكستان

- تاريخ تركمنستان

- Former countries in Central Asia

- خانيات

- تأسيسات 1500 في آسيا