اللغة الڤيتنامية

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| قالب:Contains Nom text | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

اللغة الفيتنامية (tiếng Việt) هي اللغة الرسمية لفيتنام، وهي اللغة الأم للفيتناميين الذين يمثلون 86 % من سكان فيتنام. تستخدم اللغة أيضاً في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية، وكمبوديا، وفرنسا، وأستراليا، والصين، ودول أخرى. يستخدمها 70 إلى 73 ميلون متحدث كلغة أم. العديد من كلمات اللغة مقتبسة من اللغة الصينية. تستخدم اللغة اليوم الكتابة اللاتينية مع علامات صوتية إضافية لبعض الألفاظ.

المعجم

Similes

Vietnamese has two types of similes: meaning similes and rhyming similes. The following is an example of a rhyming simile:

- Nghèo như con mèo

- [ŋɛ̀w ɲɨ̄ kɔ̄n mɛ̀w]

- "Poor as a cat"

Compare the above rhyming Vietnamese example to the English phrase "(as) drunk as a skunk", which is also a rhyming simile, and "(as) poor as a church mouse", which is only semantic.[5]

الصوتيات

الصوائت

Like other Southeast Asian languages, Vietnamese has a comparatively large number of vowels.

Below is a vowel diagram of Hanoi Vietnamese (including centering diphthongs):

Front Central Back Centering ia~iê [iə̯] ưa~ươ [ɨə̯] ua~uô [uə̯] Close i/y [i] ư [ɨ] u [u] Close-mid/

Midê [e] ơ [əː]

â [ə]ô [o] Open-mid/

Opene [ɛ] a [aː]

ă [a]o [ɔ]

Front and central vowels (i, ê, e, ư, â, ơ, ă, a) are unrounded, whereas the back vowels (u, ô, o) are rounded. The vowels â [ə] and ă [a] are pronounced very short, much shorter than the other vowels. Thus, ơ and â are basically pronounced the same except that ơ [əː] is of normal length while â [ə] is short – the same applies to the vowels long a [aː] and short ă [a].[6] There are restrictions on the high offglides: /j/ cannot occur after a front vowel (i, ê, e) nucleus and /w/ cannot occur after a back vowel (u, ô, o) nucleus.[7]

/w/ offglide /j/ offglide Front Central Back Centering iêu [iə̯w] ươu [ɨə̯w] ươi [ɨə̯j] uôi [uə̯j] Close iu [iw] ưu [ɨw] ưi [ɨj] ui [uj] Close-mid/

Midêu [ew] –

âu [əw]ơi [əːj]

ây [əj]ôi [oj] Open-mid/

Openeo [ɛw] ao [aːw]

au [aw]ai [aːj]

ay [aj]oi [ɔj]

الصوامت

The consonants that occur in Vietnamese are listed below in the Vietnamese orthography with the phonetic pronunciation to the right.

Labial Dental/

AlveolarRetroflex Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal m [m] n [n] nh [ɲ] ng/ngh [ŋ] Stop tenuis p [p] t [t] tr [ʈ] ch [c] c/k/q [k] aspirated th [tʰ] glottalized b [[Voiced bilabial implosive| [ɓ]]] đ [[Voiced alveolar implosive| [ɗ]]] Fricative voiceless ph [f] x [s] s [ʂ] kh [x] h [h] voiced v [v] d/gi [z~j] g/gh [ɣ] Approximant l [l] y/i [j] u/o [w] Rhotic r [r]

Some consonant sounds are written with only one letter (like "p"), other consonant sounds are written with a digraph (like "ph"), and others are written with more than one letter or digraph (the velar stop is written variously as "c", "k", or "q").

التنغيم

Each Vietnamese syllable is pronounced with an inherent tone,[8] centered on the main vowel or group of vowels. Tones differ in:

- length (duration)

- pitch contour (i.e. pitch melody)

- pitch height

- phonation

Tone is indicated by diacritics written above or below the vowel (most of the tone diacritics appear above the vowel; however, the nặng tone dot diacritic goes below the vowel).[9] The six tones in the northern varieties (including Hanoi), with their self-referential Vietnamese names, are:

| الاسم | الوصف | التشكيل | مثال | صائت عينة |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ngang 'level' | mid level | (no mark) | ma 'ghost' | a |

| huyền 'hanging' | low falling (often breathy) | ` (grave accent) | mà 'but' | à |

| sắc 'sharp' | high rising | ´ (acute accent) | má 'cheek, mother (southern)' | á |

| hỏi 'asking' | mid dipping-rising | ̉ (hook above) | mả 'tomb, grave' | ả |

| ngã 'tumbling' | high breaking-rising | ˜ (tilde) | mã 'horse (Sino-Vietnamese), code' | ã |

| nặng 'heavy' | low falling constricted (short length) | ̣ (dot below) | mạ 'rice seedling' | ạ |

Other dialects of Vietnamese have fewer tones (typically only five).

In Vietnamese poetry, tones are classed into two groups: (tone pattern)

| Tone group | Tones within tone group |

|---|---|

| bằng "level, flat" | ngang and huyền |

| trắc "oblique, sharp" | sắc, hỏi, ngã, and nặng |

Words with tones belonging to a particular tone group must occur in certain positions within the poetic verse.

Vietnamese Catholics practice a distinctive style of prayer recitation called đọc kinh, in which each tone is assigned a specific note or sequence of notes.

تنويعات اللغة

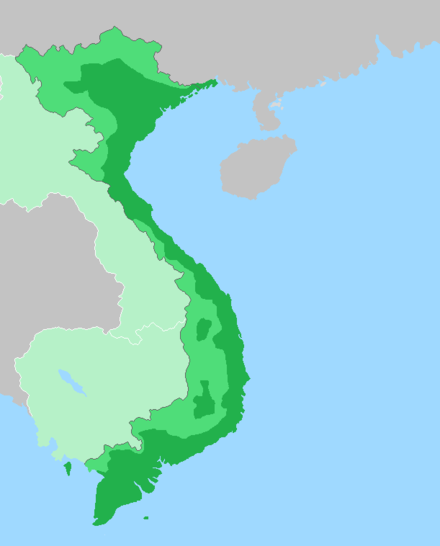

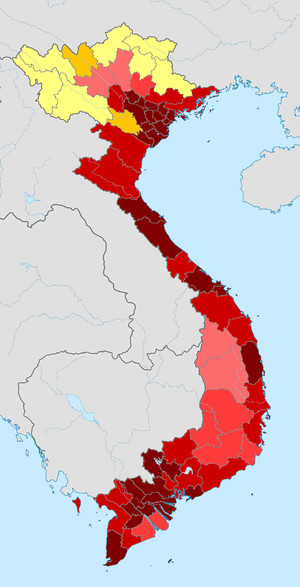

The Vietnamese language has several mutually intelligible regional varieties (or dialects). The five main dialects are as follows:[10]

| منطقة اللهجة | Localities | Names under French colonization |

|---|---|---|

| الڤيتنامية الشمالية | Hanoi, Haiphong, Red River Delta, Northwest and Northeast | Tonkinese |

| ڤيتنامية شمال الوسط (أو المنطقة IV) | Thanh Hoá, Nghệ An, Hà Tĩnh | Annamese |

| الڤيتنامية الوسطى | Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, Huế, Thừa Thiên | Annamese |

| ڤيتنامية جنوب الوسط (or Area V) | Đà Nẵng, Quảng Nam, Quảng Ngãi, Bình Định, Phú Yên, Nha Trang | Annamese |

| الڤيتنامية الجنوبية | Bà Rịa-Vũng Tàu, Ho Chi Minh City, Lâm Đồng, Mekong Delta | Cochinchinese |

المعجم

| Northern | Northern Central | Southern | English gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| này | ni, nì | này | "this" |

| thế này | như ri | như vầy | "thus, this way" |

| đấy | nớ, tê | đó | "that" |

| thế, thế ấy | rứa, rứa tê | vậy, vậy đó | "thus, so, that way" |

| kia, kìa | tê, tề | đó | "that yonder" |

| đâu | mô | đâu | "where" |

| nào | mồ | nào | "which" |

| tại sao | răng | tại sao | "why" |

| thế nào, như nào | răng, làm răng | làm sao | "how" |

| tôi | tui | tui | "I, me (polite)" |

| tao | tau | tao | "I, me (arrogant, familiar)" |

| chúng tao | choa, bọn choa | tụi tao, tụi tui | "we, us (but not you, colloquial, familiar)" |

| mày | mi | mày | "you (thou) (arrogant, familiar)" |

| chúng mày | bây, bọn bây | tụi mầy, tụi bây | "you guys, y'all (arrogant, familiar)" |

| chúng nó | bọn nớ | tụi nó | "they/them (arrogant, familiar)" |

| ông ấy | ông nớ | ổng | "he/him, that gentleman, sir" |

| bà ấy | bà nớ | bả | "she/her, that lady, madam" |

| anh ấy | anh nớ | ảnh | "he/him, that young man (of equal status)" |

| ruộng | nương | ruộng,rẫy | "field" |

| bát | đọi | chén | "rice bowl" |

| bẩn | nhớp | dơ | "dirty" |

| muôi | môi | vá | "ladle" |

| đầu | trốc | đầu | "head" |

| lười | nhác | làm biếng | "lazy" |

| ô tô | ô tô | xe hơi | "car" |

| thìa | thìa | muỗng | "spoon" |

الصوامت

The syllable-initial ch and tr digraphs are pronounced distinctly in North-central, Central, and Southern varieties, but are merged in Northern varieties (i.e. they are both pronounced the same way). The North-central varieties preserve three distinct pronunciations for d, gi, and r whereas the North has a three-way merger and the Central and South have a merger of d and gi while keeping r distinct. At the end of syllables, palatals ch and nh have merged with alveolars t and n, which, in turn, have also partially merged with velars c and ng in Central and Southern varieties.

| Syllable position | Orthography | Northern | North-central | Central | Southern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| syllable-initial | x | [s] | [s] | ||

| s | [ʂ] | [s, ʂ][12] | |||

| ch | [c] | [c] | |||

| tr | [ʈ] | [c, ʈ][12] | |||

| r | [z] | [r] | |||

| d | [ɟ] | [j] | [j] | ||

| gi | [z] | ||||

| v | [v] | [v, j][13] | |||

| syllable-final | t | [t] | [k] | ||

| c | [k] | ||||

| t after i, ê |

[t] | [t] | |||

| ch | [k̟] | ||||

| t after u, ô |

[t] | [kp] | |||

| c after u, ô, o |

[kp] | ||||

| n | [n] | [ŋ] | |||

| ng | [ŋ] | ||||

| n after i, ê |

[n] | [n] | |||

| nh | [ŋ̟] | ||||

| n after u, ô |

[n] | [ŋm] | |||

| ng after u, ô, o |

[ŋm] | ||||

In addition to the regional variation described above, there is also a merger of l and n in certain rural varieties:

| Orthography | "Mainstream" varieties | Rural varieties |

|---|---|---|

| n | [n] | [n] |

| l | [l] |

التنغيم

Generally, the Northern varieties have six tones while those in other regions have five tones. The hỏi and ngã tones are distinct in North and some North-central varieties (although often with different pitch contours) but have merged in Central, Southern, and some North-central varieties (also with different pitch contours). Some North-central varieties (such as Hà Tĩnh Vietnamese) have a merger of the ngã and nặng tones while keeping the hỏi tone distinct. Still other North-central varieties have a three-way merger of hỏi, ngã, and nặng resulting in a four-tone system. In addition, there are several phonetic differences (mostly in pitch contour and phonation type) in the tones among dialects.

| Tone | Northern | North-central | Central | Southern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinh | Thanh Chương |

Hà Tĩnh | ||||

| ngang | ˧ 33 | ˧˥ 35 | ˧˥ 35 | ˧˥ 35, ˧˥˧ 353 | ˧˥ 35 | ˧ 33 |

| huyền | ˨˩̤ 21̤ | ˧ 33 | ˧ 33 | ˧ 33 | ˧ 33 | ˨˩ 21 |

| sắc | ˧˥ 35 | ˩ 11 | ˩ 11, ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˧˥ 35 |

| hỏi | ˧˩˧̰ 31̰3 | ˧˩ 31 | ˧˩ 31 | ˧˩̰ʔ 31̰ʔ | ˧˩˨ 312 | ˨˩˦ 214 |

| ngã | ˧ʔ˥ 3ʔ5 | ˩˧̰ 13̰ | ˨̰ 22̰ | |||

| nặng | ˨˩̰ʔ 21̰ʔ | ˨ 22 | ˨̰ 22̰ | ˨̰ 22̰ | ˨˩˨ 212 | |

The table above shows the pitch contour of each tone using Chao tone number notation (where 1 = lowest pitch, 5 = highest pitch); glottalization (creaky, stiff, harsh) is indicated with the ⟨◌̰⟩ symbol; murmured voice with ⟨◌̤⟩; glottal stop with ⟨ʔ⟩; sub-dialectal variants are separated with commas. (See also the tone section below.)

النحو

نظم الكتابة

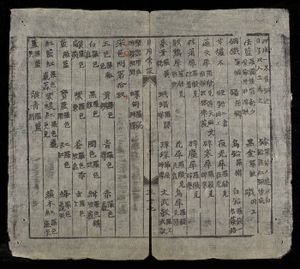

Up to the late 19th century, two writing systems based on Chinese characters were used in Vietnam.[14] All formal writing, including government business, scholarship and formal literature, was done in Classical Chinese (chữ nho 𡨸儒 "scholar's characters").

Folk literature in Vietnamese was recorded using the chữ Nôm script, in which many Chinese characters were borrowed and many more modified and invented to represent native Vietnamese words. Created in the 13th century or earlier, the Nôm writing reached its zenith in the 18th century when many Vietnamese writers and poets composed their works in Nôm, most notably Nguyễn Du and Hồ Xuân Hương (dubbed "the Queen of Nôm poetry"). However it was only used for official purposes during the brief Hồ and Tây Sơn dynasties.

A Vietnamese Catholic, Nguyễn Trường Tộ, sent petitions to the Court which suggested a Chinese character-based syllabary which would be used for Vietnamese sounds; however, his petition failed. The French colonial administration sought to eliminate the Chinese writing system, Confucianism, and other Chinese influences from Vietnam by getting rid of Nôm.[15]

A romanization of Vietnamese was codified in the 17th century by the French Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1660), based on works of earlier Portuguese missionaries Gaspar do Amaral and António Barbosa. This Vietnamese alphabet (chữ quốc ngữ or "national script") was gradually expanded from its initial domain in Christian writing to become more popular among the general public. However, the Romanized script did not come to predominate until the beginning of the 20th century, when education became widespread and a simpler writing system was found more expedient for teaching and communication with the general population. Under French Indochina colonial rule, French superseded Chinese in administration. Vietnamese written with the alphabet became required for all public documents in 1910 by issue of a decree by the French Résident Supérieur of the protectorate of Tonkin. By the middle of the 20th century virtually all writing was done in chữ quốc ngữ, which became the official script on independence. Chữ nho was still in use on early North Vietnamese and late French Indochinese banknotes issued after World War II,[16][17] but fell out of official use shortly thereafter. Only a few scholars and some extremely elderly people are able to read chữ Nôm today. In China, members of the Jing minority still write in chữ Nôm.

Changes in the script were made by French scholars and administrators and by conferences held after independence during 1954–1974. The script now reflects a so-called Middle Vietnamese dialect that has vowels and final consonants most similar to northern dialects and initial consonants most similar to southern dialects (Nguyễn 1996). This Middle Vietnamese is presumably close to the Hanoi variety as spoken sometime after 1600 but before the present. (This is not unlike how English orthography is based on the Chancery Standard of Late Middle English, with many spellings retained even after the Great Vowel Shift.)

الدعم الحاسوبي

The Unicode character set contains all Vietnamese characters and the Vietnamese currency symbol. On systems that do not support Unicode, many 8-bit Vietnamese code pages are available such as Vietnamese Standard Code for Information Interchange (VSCII) or Windows-1258. Where ASCII must be used, Vietnamese letters are often typed using the VIQR convention, though this is largely unnecessary with the increasing ubiquity of Unicode. There are many software tools that help type true Vietnamese text on US keyboards, such as WinVNKey and Unikey on Windows, or MacVNKey on Macintosh.

التاريخ

It seems likely that in the distant past, Vietnamese shared more characteristics common to other languages in the Austroasiatic family, such as an inflectional morphology and a richer set of consonant clusters, which have subsequently disappeared from the language. However, Vietnamese appears to have been heavily influenced by its location in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, with the result that it has acquired or converged toward characteristics such as isolating morphology and phonemically distinctive tones, through processes of tonogenesis. These characteristics have become part of many of the genetically unrelated languages of Southeast Asia; for example, Tsat (a member of the Malayo-Polynesian group within Austronesian), and Vietnamese each developed tones as a phonemic feature.

The ancestor of the Vietnamese language was previously believed to have been originally based in the area of the Red River in what is now northern Vietnam but this theory has been widely rejected by modern Western scholarship, based on historical records and linguistic evidence. The Red River Delta region is now considered to be originally Tai-speaking, ethnic Li people in particular, or Austronesian-speaking. The area is believed to have become Vietnamese-speaking only between the seventh and ninth centuries AD, or even as late as the tenth century, as a result of immigration from the south, i.e., modern central Vietnam, where the highly distinctive and conservative North-Central Vietnamese dialects are spoken today. Therefore, the region of origin of Vietnamese (and the earlier Viet–Muong) was well south of the Red River.[18][19][20][21][22]

Like the ethnonym Lao, the name Yue/Việt originally referred to Tai–Kadai-speaking groups. In northern Vietnam, these later adopted Viet–Muong and further north Chinese varieties, where the designation Yue Chinese preserves the ethnonym. (Both in Vietnam and southern China, however, many Tai–Kadai languages remain in use.) This explains the fact that the same ethnonym Yue ~ Việt is associated with groups that speak Tai–Kadai, Austroasiatic and Chinese languages, which are typologically similar and share significant amounts of lexicon, but have different origins.

Linguists Sagart (2011) and Bellwood (2013) favour the middle Yangzte, although there is no direct linguistic evidence for this, and the expansion of the phylum in its present form would have to begin further south.[23]

Distinctive tonal variations emerged during the subsequent expansion of the Vietnamese language and people into what is now central and southern Vietnam through conquest of the ancient nation of Champa and the Khmer people of the Mekong Delta in the vicinity of present-day Ho Chi Minh City, also known as Saigon.

Vietnamese was primarily influenced by Chinese, which came to predominate politically in the 2nd century BC. After Vietnam achieved independence in the 10th century, the ruling class adopted Classical Chinese as the medium of government, scholarship and literature. With the dominance of Chinese came radical importation of Chinese vocabulary and grammatical influence. A portion of the Vietnamese lexicon in all realms consists of Sino-Vietnamese words (They comprise about a third of the Vietnamese lexicon, and may account for as much as 60% of the vocabulary used in formal texts.[24])

When France invaded Vietnam in the late 19th century, French gradually replaced Chinese as the official language in education and government. Vietnamese adopted many French terms, such as đầm (dame, from madame), ga (train station, from gare), sơ mi (shirt, from chemise), and búp bê (doll, from poupée). In addition, many Sino-Vietnamese terms were devised for Western ideas imported through the French.

Henri Maspero described six periods of the Vietnamese language:[25][26]

- Pre-Vietnamese, also known as Proto-Viet–Muong or Proto-Vietnamuong, the ancestor of Vietnamese and the related Muong language.

- Proto-Vietnamese, the oldest reconstructable version of Vietnamese, dated to just before the entry of massive amounts of Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary into the language, c. 7th to 9th century AD? At this state, the language had three tones.

- Archaic Vietnamese, the state of the language upon adoption of the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary, c. 10th century AD.

- Ancient Vietnamese, the language represented by Chữ Nôm (c. 15th century) and the Chinese–Vietnamese glossary Huáyí Yìyǔ (الصينية: 华夷译语 c. 15th century). By this point, a tone split had happened in the language, leading to six tones but a loss of contrastive voicing among consonants.

- Middle Vietnamese, the language of the Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum of the Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (c. 17th century).

- Modern Vietnamese, from the 19th century.

Proto-Viet–Muong

The following diagram shows the phonology of Proto-Viet–Muong (the nearest ancestor of Vietnamese and the closely related Muong language), along with the outcomes in the modern language:[27][28][29][30]

Labial Dental/Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal Stop tenuis *p > b *t > đ *c > ch *k > k/c/q *ʔ > # voiced *b > b *d > đ *ɟ > ch *ɡ > k/c/q aspirated *pʰ > ph *tʰ > th *kʰ > kh voiced glottalized *ɓ > m *ɗ > n *ʄ > nh [1] Nasal *m > m *n > n *ɲ > nh *ŋ > ng/ngh Affricate *tʃ > x [2] Fricative voiceless *s > t *h > h voiced [3] *(β) > v [4] *(ð) > d *(r̝) > r [5] *(ʝ) > gi *(ɣ) > g/gh Approximant *w > v *l > l *r > r *j > d

^1 According to Ferlus, */tʃ/ and */ʄ/ are not accepted by all researchers. Ferlus 1992[27] also had additional phonemes */dʒ/ and */ɕ/.

^2 The fricatives indicated above in parentheses developed as allophones of stop consonants occurring between vowels (i.e. when a minor syllable occurred). These fricatives were not present in Proto-Viet–Muong, as indicated by their absence in Muong, but were evidently present in the later Proto-Vietnamese stage. Subsequent loss of the minor-syllable prefixes phonemicized the fricatives. Ferlus 1992[27] proposes that originally there were both voiced and voiceless fricatives, corresponding to original voiced or voiceless stops, but Ferlus 2009[28] appears to have abandoned that hypothesis, suggesting that stops were softened and voiced at approximately the same time, according to the following pattern:

- *p, *b > /β/

- *t, *d > /ð/

- *s > /r̝/

- *c, *ɟ, *tʃ > /ʝ/

- *k, *ɡ > /ɣ/

^3 In Middle Vietnamese, the outcome of these sounds was written with a hooked b (![]() ), representing a /β/ that was still distinct from v (then pronounced /w/). See below.

), representing a /β/ that was still distinct from v (then pronounced /w/). See below.

^4 It is unclear what this sound was. According to Ferlus 1992,[27] in the Archaic Vietnamese period (c. 10th century AD, when Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary was borrowed) it was *r̝, distinct at that time from *r.

The following initial clusters occurred, with outcomes indicated:

- *pr, *br, *tr, *dr, *kr, *gr > /kʰr/ > /kʂ/ > s

- *pl, *bl > MV bl > Northern gi, Southern tr

- *kl, *gl > MV tl > tr

- *ml > MV ml > mnh > nh

- *kj > gi

Note also that a large number of words were borrowed from Middle Chinese, forming part of the Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary. These caused the original introduction of the retroflex sounds /ʂ/ and /ʈ/ (modern s, tr) into the language.

أصل النغمات

Proto-Viet–Muong had no tones to speak of. The tones later developed in some of the daughter languages from distinctions in the initial and final consonants. Vietnamese tones developed as follows:

Register Initial consonant Smooth ending Glottal ending Fricative ending High (first) register Voiceless A1 ngang "level" B1 sắc "sharp" C1 hỏi "asking" Low (second) register Voiced A2 huyền "hanging" B2 nặng "heavy" C2 ngã "tumbling"

Glottal-ending syllables ended with a glottal stop /ʔ/, while fricative-ending syllables ended with /s/ or /h/. Both types of syllables could co-occur with a resonant (e.g. /m/ or /n/).

أمثلة

The Tale of Kieu is an epic narrative poem by the celebrated poet Nguyễn Du, (阮攸), which is often considered the most significant work of Vietnamese literature. It was originally written in Chữ Nôm (titled Đoạn Trường Tân Thanh 斷腸新聲) and is widely taught in Vietnam today.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Citizens belonging to minorities, which traditionally and on long-term basis live within the territory of the Czech Republic, enjoy the right to use their language in communication with authorities and in front of the courts of law (for the list of recognized minorities see National Minorities Policy of the Government of the Czech Republic, Belorussian and Vietnamese since 4 July 2013, see Česko má nové oficiální národnostní menšiny. Vietnamce a Bělorusy). The article 25 of the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms ensures right of the national and ethnic minorities for education and communication with authorities in their own language. Act No. 500/2004 Coll. (The Administrative Rule) in its paragraph 16 (4) (Procedural Language) ensures, that a citizen of the Czech Republic, who belongs to a national or an ethnic minority, which traditionally and on long-term basis lives within the territory of the Czech Republic, have right to address an administrative agency and proceed before it in the language of the minority. In the case that the administrative agency doesn't have an employee with knowledge of the language, the agency is bound to obtain a translator at the agency's own expense. According to Act No. 273/2001 (About The Rights of Members of Minorities) paragraph 9 (The right to use language of a national minority in dealing with authorities and in front of the courts of law) the same applies for the members of national minorities also in front of the courts of law.

- ^ "Languages of ASEAN". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ From Ethnologue (2009, 2013)

- ^ "The 2009 Vietnam Population and Housing Census: Completed Results". General Statistics Office of Vietnam: Central Population and Housing Census Steering Committee. June 2010. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See p. 98 in Thuy Nga Nguyen and Ghil'ad Zuckermann (2012), "Stupid as a Coin: Meaning and Rhyming Similes in Vietnamese", International Journal of Language Studies 6(4), 97–118.

- ^ There are different descriptions of Hanoi vowels. Another common description is that of Thompson (1965):

Front Central Back unrounded rounded Centering ia~iê [iə̯] ưa~ươ [ɯə̯] ua~uô [uə̯] Close i [i] ư [ɯ] u [u] Close-mid ê [e] ơ [ɤ] ô [o] Open-mid e [ɛ] ă [ɐ] â [ʌ] o [ɔ] Open a [a]

- ^ The lack of diphthong consisting of a ơ + back offglide (i.e., [əːw]) is an apparent gap.

- ^ Called thanh điệu or thanh in Vietnamese

- ^ Note that the name of each tone has the corresponding tonal diacritic on the vowel.

- ^ Sources on Vietnamese variation include: Alves (forthcoming), Alves & Nguyễn (2007), Emeneau (1947), Hoàng (1989), Honda (2006), Nguyễn, Đ.-H. (1995), Pham (2005), Thompson (1991[1965]), Vũ (1982), Vương (1981).

- ^ Table data from Hoàng (1989).

- ^ أ ب In southern dialects, ch and tr are increasingly being merged as [c]. Similarly, x and s are increasingly being merged as [s].

- ^ In southern dialects, v is increasingly being pronounced [v] among educated speakers. Less educated speakers have [j] more consistently throughout their speech.

- ^ DeFrancis, John (1977). Colonialism and language policy in Viet Nam. Mouton. ISBN 978-90-279-7643-7.

- ^ Marr, David G. (1984). Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920–1945. University of California Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-520-90744-7.

- ^ "French Indochina 500 Piastres 1951". art-hanoi.com.

- ^ "North Vietnam 5 Dong 1946". art-hanoi.com.

- ^ John D. Phan, 'Re-Imagining “Annam”: A New Analysis of Sino-Viet-Muong Linguistic Contact', Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, vol.4 (2010)

- ^ Schliesinger, Joachim (2018). Origin of the Tai People 6―Northern Tai-Speaking People of the Red River Delta and Their Habitat Today Volume 6 of Origin of the Tai People. Booksmango,. pp. 3–4, 22, 50, 54. ISBN 1641531835.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Chamberlain, James R. (2000). "The origin of the Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history". In Burusphat, Somsonge (ed.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Tai Studies, July 29–31, 1998 (PDF). Bangkok, Thailand: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University. pp. 97–127. ISBN 974-85916-9-7. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ Schliesinger, Joachim (2018). Origin of the Tai People 5―Cradle of the Tai People and the Ethnic Setup Today Volume 5 of Origin of the Tai People. Booksmango,. pp. 21, 97. ISBN 1641531827.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|title=at position 79 (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam". Journal of the Siam Society. Volume 104, .

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Blench, Roger (2014), Reconstructing Austroasiatic prehistory. Chapter in the forthcoming Jenny, M. & P. Sidwell (eds.). forthcoming 2015. Handbook of the Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill, p. 1.

- ^ DeFrancis (1977), p. 8.

- ^ Maspero, Henri (1912). "Études sur la phonétique historique de la langue annamite" [Studies on the phonetic history of the Annamite language]. Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in الفرنسية). 12 (1): 10.

- ^ Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (2009), "Vietnamese", in Comrie, Bernard, The World's Major Languages (2nd ed.), Routledge, pp. 677–692, ISBN 978-0-415-35339-7.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ferlus, Michel (1992), "Histoire abrégée de l'évolution des consonnes initiales du Vietnamien et du Sino-Vietnamien", Mon–Khmer Studies 20: 111–125, https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00923038.

- ^ أ ب Ferlus, Michel (2009), "A layer of Dongsonian vocabulary in Vietnamese", Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 1: 95–109, https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00932218.

- ^ Ferlus, Michel (1982), "Spirantisation des obstruantes médiales et formation du système consonantique du vietnamien", Cahiers de linguistique – Asie Orientale 11 (1): 83–106, doi:, https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01063845.

- ^ Thompson, Laurence C., "Proto-Viet–Muong Phonology", Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications, Austroasiatic Studies Part II (University of Hawai'i Press) 13: 1113–1203.

ببليوگرافيا

العامة

- Dương, Quảng-Hàm. (1941). Việt-nam văn-học sử-yếu [Outline history of Vietnamese literature]. Saigon: Bộ Quốc gia Giáo dục.

- Emeneau, M. B. (1947). "Homonyms and puns in Annamese". Language, 23(3), 239–244. DOI:10.2307/409878. JSTOR 409878.

- Emeneau, M. B. (1951). Studies in Vietnamese (Annamese) grammar. University of California publications in linguistics (Vol. 8). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hashimoto, Mantaro. (1978). "Current developments in Sino-Vietnamese studies". Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 6, 1–26. JSTOR 23752818

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1995). NTC's Vietnamese–English dictionary (updated ed.). NTC language dictionaries. Lincolnwood, Illinois: NTC Pub. Press.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1997). Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Rhodes, Alexandre de. (1991). Từ điển Annam-Lusitan-Latinh [original: Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum]. (L. Thanh, X. V. Hoàng, & Q. C. Đỗ, Trans.). Hanoi: Khoa học Xã hội. (Original work published 1651).

- Thompson, Laurence C. (1991). A Vietnamese reference grammar. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. (Original work published 1965)

- Uỷ ban Khoa học Xã hội Việt Nam. (1983). Ngữ-pháp tiếng Việt [Vietnamese grammar]. Hanoi: Khoa học Xã hội.

النظام الصوتي

- Brunelle, Marc. (2009). "Tone perception in Northern and Southern Vietnamese". Journal of Phonetics, 37(1), 79–96. DOI:10.1016/j.wocn.2008.09.003.

- Brunelle, Marc. (2009). "Northern and Southern Vietnamese Tone Coarticulation: A Comparative Case Study". Journal of Southeast Asian Linguistics, 1, 49–62.

- Kirby, James P. (2011). "Vietnamese (Hanoi Vietnamese)" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 41 (3): 381–392. doi:10.1017/S0025100311000181.

- Michaud, Alexis. (2004). "Final consonants and glottalization: New perspectives from Hanoi Vietnamese". Phonetica 61(2–3), 119–146. DOI:10.1159/000082560.

- Nguyễn, Văn Lợi; & Edmondson, Jerold A. (1998). "Tones and voice quality in modern northern Vietnamese: Instrumental case studies". Mon–Khmer Studies, 28, 1–18

- Thompson, Laurence E. (1959). "Saigon phonemics". Language, 35(3), 454–476. DOI:10.2307/411232. JSTOR 411232.

Language variation

- Alves, Mark J. 2007. "A Look At North-Central Vietnamese" In SEALS XII Papers from the 12th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2002, edited by Ratree Wayland et al. Canberra, Australia, 1–7. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University

- Alves, Mark J.; & Nguyễn, Duy Hương. (2007). "Notes on Thanh-Chương Vietnamese in Nghệ-An province". In M. Alves, M. Sidwell, & D. Gil (Eds.), SEALS VIII: Papers from the 8th annual meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 1998 (pp. 1–9). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies

- Hoàng, Thị Châu. (1989). Tiếng Việt trên các miền đất nước: Phương ngữ học [Vietnamese in different areas of the country: Dialectology]. Hà Nội: Khoa học xã hội.

- Honda, Koichi. (2006). "F0 and phonation types in Nghe Tinh Vietnamese tones"[dead link]. In P. Warren & C. I. Watson (Eds.), Proceedings of the 11th Australasian International Conference on Speech Science and Technology (pp. 454–459). Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland.

- Pham, Andrea Hoa. (2005). "Vietnamese tonal system in Nghi Loc: A preliminary report". In C. Frigeni, M. Hirayama, & S. Mackenzie (Eds.), Toronto working papers in linguistics: Special issue on similarity in phonology (Vol. 24, pp. 183–459). Auckland, New Zealand: University of Auckland.

- Vũ, Thanh Phương. (1982). "Phonetic properties of Vietnamese tones across dialects". In D. Bradley (Ed.), Papers in Southeast Asian linguistics: Tonation (Vol. 8, pp. 55–75). Sydney: Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University.

- Vương, Hữu Lễ. (1981). "Vài nhận xét về đặc diểm của vần trong thổ âm Quảng Nam ở Hội An" [Some notes on special qualities of the rhyme in local Quảng Nam speech in Hội An]. In Một Số Vấn Ðề Ngôn Ngữ Học Việt Nam [Some linguistics issues in Vietnam] (pp. 311–320). Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Ðại Học và Trung Học Chuyên Nghiệp.

الذرائع

- Luong, Hy Van. (1987). "Plural markers and personal pronouns in Vietnamese person reference: An analysis of pragmatic ambiguity and negative models". Anthropological Linguistics, 29(1), 49–70. JSTOR 30028089

- Sophana, Srichampa. (2004). "Politeness strategies in Hanoi Vietnamese speech". Mon–Khmer Studies, 34, 137–157

- Sophana, Srichampa. (2005). "Comparison of greetings in the Vietnamese dialects of Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City". Mon–Khmer Studies, 35, 83–99

تاريخي ومقارن

- Alves, Mark J. (2001). "What's So Chinese About Vietnamese?" (PDF). In Thurgood, Graham W. (ed.). Papers from the Ninth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 221–242. ISBN 978-1-881044-27-7.

- Cooke, Joseph R. (1968). Pronominal reference in Thai, Burmese, and Vietnamese. University of California publications in linguistics (No. 52). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gregerson, Kenneth J. (1969). "A study of Middle Vietnamese phonology". Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoises, 44, 135–193. (Reprinted in 1981).

- Maspero, Henri (1912). "Etudes sur la phonétique historique de la langue annamite. Les initiales". Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. 12 (1): 1–124.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1986). "Alexandre de Rhodes' dictionary". Papers in Linguistics, 19, 1–18. DOI:10.1080/08351818609389247.

- Shorto, Harry L. edited by Sidwell, Paul, Cooper, Doug and Bauer, Christian (2006). A Mon–Khmer comparative dictionary. Canberra: Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN

- Thompson, Laurence E. (1967). "The history of Vietnamese final palatals". Language, 43(1), 362–371. DOI:10.2307/411402. JSTOR 411402.

الخط

- Haudricourt, André-Georges (1949). "Origine des particularités de l'alphabet vietnamien". Dân Việt-Nam. 3: 61–68.

- English translation: Michaud, Alexis; Haudricourt, André-Georges (2010). "The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet". Mon-Khmer Studies. 39: 89–104.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1955). Quốc-ngữ: The modern writing system in Vietnam. Washington, DC: Author.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1990). "Graphemic borrowing from Chinese: The case of chữ nôm, Vietnam's demotic script". Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, 61, 383–432.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1996). Vietnamese. In P. T. Daniels, & W. Bright (Eds.), The world's writing systems, (pp. 691–699). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

التعليم

- Nguyen, Bich Thuan. (1997). Contemporary Vietnamese: An intermediate text. Southeast Asian language series. Northern Illinois University, Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

- Healy, Dana. (2004). Teach Yourself Vietnamese. Teach Yourself. Chicago: McGraw-Hill. ISBN

- Hoang, Thinh; Nguyen, Xuan Thu; Trinh, Quynh-Tram; (2000). Vietnamese phrasebook, (3rd ed.). Hawthorn, Vic.: Lonely Planet. ISBN

- Moore, John. (1994). Colloquial Vietnamese: A complete language course. London: Routledge.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1967). Read Vietnamese: A graded course in written Vietnamese. Rutland, Vermont: C.E. Tuttle.

- Lâm, Lý-duc; Emeneau, M. B.; von den Steinen, Diether. (1944). An Annamese reader. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley.

- Nguyễn, Đăng Liêm. (1970). Vietnamese pronunciation. PALI language texts: Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

وصلات خارجية

- دروس أونلاين

- Online Vietnamese lessons from Northern Illinois University

- Learn Vietnamese with Annie, video lessons by a native speaker

- معجم

- Vietnamese Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- Swadesh list of Vietnamese basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Diccionario Vietnamita

- Nôm look-up from the Vietnamese Nôm Preservation Foundation

- Lexicon of Vietnamese words borrowed from French by Jubinell

- List of Japanese-Vietnamese Kanjis by Jubinell

- أدوات لغوية

- The Vietnamese keyboard its layout is compared with US, UK, Canada, France, and Germany's keyboards.

- The Free Vietnamese Dictionary Project

Research projects and data resources

- http://projekt.ht.lu.se/rwaai RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-93ED-5@view Vietnamese in RWAAI Digital Archive

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Pages with plain IPA

- Articles containing ڤيتنامية-language text

- CS1 errors: invisible characters

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Languages with ISO 639-1 code

- Language articles without reference field

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with dead external links from July 2018

- لغات تحليلية

- Isolating languages

- لغات كمبوديا

- لغات الصين

- لغات جمهورية التشيك

- لغات لاوس

- لغات تايوان

- لغات ڤيتنام

- Subject–verb–object languages

- Vietic languages

- اللغة الڤيتنامية