معركة قوصوه

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

معركة قوصوه أو معركة كوسوفو (تركية: Kosova Savaşı; بالصربية: Косовска битка) نشبت في 15 يونيو 1389 م/791 هـ بين جيش العثمانيين الغازي بقيادة السلطان مراد الأول، وجيوش البلقان المكونة من الجيش الصربي والألباني بقيادة ملك الصرب "ڤوك برانكوڤتش". The battle was fought on the Kosovo field in the territory ruled by Serbian nobleman Vuk Branković, in what is today Kosovo,[أ] about 5 كيلومتر (3.1 mi) northwest of the modern city of Pristina. The army under Prince Lazar consisted of his own troops, a contingent led by Branković, and a contingent sent from Bosnia by King Tvrtko I, commanded by Vlatko Vuković.[6] Prince Lazar was the ruler of Moravian Serbia and the most powerful among the Serbian regional lords of the time, while Branković ruled the District of Branković and other areas, recognizing Lazar as his overlord.

Reliable historical accounts of the battle are scarce.[12] The bulk of both armies were wiped out, and Lazar and Murad were killed. However, Serbian manpower was depleted and had no capacity to field large armies against future Ottoman campaigns, which relied on new reserve forces from Anatolia. Consequently, the Serbian principalities that were not already Ottoman vassals, became so in the following years.

سبب الحرب

عندما تولى مراد بن أورخان الحكم واصل جهود أبيه في الفتح، ففتح مدينة أدرنة ونقل إليها العاصمة بعد أن كانت في بورصة، ثم فتح أراضى الدولة البيزنطية في البلقان حتى أصبحت القسطنطينية محاصرة تمامًا بالأراضى العثمانية، وصارت الأراضى العثمانية متاخمة لكل من الصرب والبلغار وألبانيا فانزعج ملوك أوربا وأرسل أمراء تلك المناطق إلى ملوك أوربا الغربية وإلى البابا يستنجدون بهم ضد المسملين، فدعا البابا إلى قيام حرب صليبية جديدة.

ثم هاجم ملك الصرب أدرنة وكان مراد غائباً عنها، فلما علم بأمر الهجوم عاد وحارب الصرب وهزمهم فقام ملك الصرب الجديد بالتحالف مع أمير بلغاريا لمحاربة العثمانيين، فلما قامت الحرب هرب أمير بلغاريا ثم اصطلح الصرب والبلغار مع الدولة العثمانية نظير حماية سنوية يدفعونها لهم، ولكن الصرب نقضوا عهدهم وتحالفوا مع ألبانيا ضد العثمانيين والتقى الفريقان في قوصوه.

الخلفية

Emperor Stefan Uroš IV Dušan "the Mighty" (r. 1331–55) was succeeded by his son Stefan Uroš V "the Weak" (r. 1355–71), whose reign was characterized by the decline of central power and the rise of numerous virtually independent principalities; this period is known as the fall of the Serbian Empire. Uroš V was neither able to sustain the great empire created by his father, nor repulse foreign threats and limit the independence of the nobility; he died childless on 4 December 1371, after much of the Serbian nobility had been destroyed by the Ottomans in the Battle of Maritsa earlier that year. Prince Lazar, ruler of the northern part of the former empire (of Moravian Serbia), was aware of the Ottoman threat and began diplomatic and military preparations for a campaign against them.

After the defeat of the Ottomans at Pločnik (1386) and Bileća (1388), Murad I, the reigning Ottoman sultan, moved his troops from Philippoupolis to Ihtiman (modern Bulgaria) in the spring of 1388. From there they traveled across Velbužd and Kratovo (modern North Macedonia). Though longer than the alternative route through Sofia and the Nišava Valley, this led the Ottoman forces to Kosovo, one of the most important crossroads in the Balkans. From Kosovo, they could attack the lands of either Prince Lazar or Vuk Branković. Having stayed in Kratovo for a time, Murad and his troops marched through Kumanovo, Preševo, and Gjilan to Pristina, where he arrived on June 14.

Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović

Sultan Murad Hüdavendigâr

While there is less information about Lazar's preparations, he gathered his troops near Niš, on the right bank of the South Morava. His forces likely remained there until he learned that Murad had moved to Velbužd, whereupon he moved across Prokuplje to Kosovo. This was the best place he could choose as a battlefield, as it gave him control of all the routes that Murad could take. The historiographical examination of the battle is challenging. No first-hand accounts from participants in the battle exist. Contemporary sources are written from widely diverging points of view and not much is discussed in them about battle tactics, army size and other battleground details.[13]

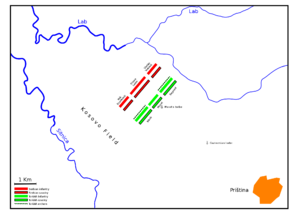

نشر القوات

The armies met at the Kosovo field. Murad headed the Ottoman army, with his sons Bayezid on his right and Yakub on his left. Around 1,000 archers were in the front line in the wings, backed up by azap and akinci; in the front center were Janissaries, behind whom was Murad, surrounded by his cavalry guard; finally, the supply train at the rear was guarded by a small number of troops.[بحاجة لمصدر] One of the Ottoman commanders was Pasha Yiğit Bey.[14]

The Serbian army had Prince Lazar at its center, Vuk on the right, and Vlatko on the left. At the front of the army were the heavy cavalry and archer cavalry on the flanks, with the infantry to the rear. While parallel, the dispositions of the armies were not symmetrical, as the Serbian center had a broader front than the Ottoman center.[بحاجة لمصدر]

المعركة

Serbian and Turkish accounts of the battle differ, making it difficult to reconstruct the course of events. It is believed that the battle commenced with Ottoman archers shooting at Serbian cavalry, who then made ready for the attack. After positioning in a wedge formation,[15] the Serbian cavalry managed to break through the Ottoman left wing, but were not as successful against the center and the right wing.

The Serbs had the initial advantage after their first charge, which significantly damaged the Ottoman wing commanded by Yakub Çelebi.[16] When the knights' charge was finished, light Ottoman cavalry and light infantry counterattacked and the Serbian heavy armor became a disadvantage. In the center, Serbian troops managed to push back Ottoman forces, except for Bayezid's wing, which barely held off the Bosnians commanded by Vlatko Vuković. Vuković thus inflicted disproportionately heavy losses on the Ottomans. The Ottomans, in a ferocious counterattack led by Bayezid, pushed the Serbian forces back and then prevailed later in the day, routing the Serbian infantry. Both flanks still held, with Vuković's Bosnian troops drifting toward the center to compensate for the heavy losses inflicted on the Serbian infantry.

Historical facts say that Vuk Branković saw that there was no hope for victory and fled to save as many men as he could after Lazar was captured. In traditional songs, however, it is said that he betrayed Lazar and left him to die in the middle of battle, rather than after Lazar was captured and the center suffered heavy losses.

Sometime after Branković's retreat from the battle, the remaining Bosnian and Serb forces yielded the field, believing that a victory was no longer possible.

As the battle turned against the Serbs, it is said that one of their knights, later identified as Miloš Obilić, pretended to have deserted to the Ottoman forces. When brought before Murad, Obilić pulled out a hidden dagger and killed the Sultan by slashing him, after which the Sultan's bodyguards immediately killed him.

دارت المعركة بعنف وحمى الوطيس وتطايرت الرؤوس وظلت الحرب سجالاً حتى فر صهر ملك الصرب "لازار" ويدعى "فوك برانكوفتش" ومعه عشرة آلاف فارس والتحق بجيش المسلمين، فدارت الدائرة على الصرب وجرح لازار وأسر فقتله العثمانيون وانتصر المسلمون.

الهجمة التركية المضادة

استشهاد مراد

أثناء تفقد الأمير مراد ساحة القتال قام صربي جريح من بين القتلى وطعنه فجأه بخنجر فقتله على الفور، وبذلك استشهد الأمير مراد في ساحة الجهاد وعمره (65) عامًا.

الأعقاب

التقارير المبكرة

The event of the battle quickly became known in Europe. Not much attention was paid to the outcome in these early rumors which circulated, but they all focused on the fact that the Ottoman Sultan had been killed in the battle. Some of the earliest reports about the battle come from the court of Tvrtko of Bosnia who in separate letters to the senate of Trogir (August 1) and the council of Florence claimed that he had defeated the Ottomans in Kosovo.[17] The response of the Florentines to Tvrtko (20 October 1389) is an important historical document as it confirms that Murad was killed during the battle and that it took place on June 28 (St. Vitus day/Vidovdan). The killer is not named, but it was one of 12 Serbian noblemen who managed to break through the Ottoman lines:

Fortunate, most fortunate are those hands of the twelve loyal lords who, having opened their way with the sword and having penetrated the enemy lines and the circle of chained camels, heroically reached the tent of Murat himself. Fortunate above all is that one who so forcefully killed such a strong vojvoda by stabbing him with a sword in the throat and belly. And blessed are all those who gave their lives and blood through the glorious manner of martyrdom as victims of the dead leader over his ugly corpse.[18]

Another Italian account, Mignanelli's work of 1416, asserted that it was Lazar who killed the Ottoman sultan.[19]

الآثار الجيوسياسية

Both armies were destroyed in the battle.[6] Both Lazar and Murad lost their lives, and the remnants of their armies retreated from the battlefield. Murad's son Bayezid killed his younger brother, Yakub Çelebi, upon hearing of their father's death, thus becoming the sole heir to the Ottoman throne.[20] The Serbs were left with too few men to defend their lands effectively, while the Turks had many more troops in the east.[6] The immediate effect of the depletion of Serbian manpower was a shift in the stance of Hungarian policy towards Serbia. Hungary tried to exploit the effects of battle and expand in northern Serbia, while the Ottomans renewed their campaign in southern Serbia as early as 1390-91. Domestically, the Serbian feudal class in response to these threats split in two factions. A northern faction supported a conciliatory, pro-Ottoman foreign policy as a means of defence of their lands against Hungary, while a southern faction which was immediately threatened by Ottoman expansion sought to establish a pro-Hungarian foreign policy. Consequently, some of the Serbian principalities that were not already Ottoman vassals became so in the following years.[6] These feudal lords - including the daughter of Prince Lazar - formed marriage ties with the new Sultan Bayezid.[21][22][23] In the wake of these marriages, Stefan Lazarević, Lazar's son, became a loyal ally of Bayezid, and contributed significant forces to many of Bayezid's future military engagements, including the Battle of Nicopolis. Some Serbian feudal lords continued to fight against the Ottomans and others were integrated in the Ottoman feudal hierarchy. The capture of Smederevo on June 20, 1459 marks the end of medieval Serbian statehood.[24]

الذكرى

The Battle of Kosovo is particularly important to Serbian history, tradition and national identity.[25]

The day of the battle, known in Serbian as Vidovdan (St. Vitus' day) and celebrated according to the Julian calendar (corresponding to 28 June Gregorian in the 20th and 21st centuries), is an important part of Serb ethnic and national identity,[26] with notable events in Serbian history falling on that day: in 1876 Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire (Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78); in 1881 Austria-Hungary and the Principality of Serbia signed a secret alliance; in 1914 the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was carried out by the Serbian Gavrilo Princip (although a coincidence that his visit fell on that day, Vidovdan added nationalist symbolism to the event[27]); in 1921 King Alexander I of Yugoslavia proclaimed the Vidovdan Constitution; in 1989, on the 600th anniversary of the battle, Serbian president Slobodan Milošević delivered the Gazimestan speech on the site of the historic battle.

The Tomb of Sultan Murad, a site in Kosovo Polje where Murad I's internal organs were buried, has gained a religious significance for local Muslims. A monument was built by Murad I's son Bayezid I at the tomb, becoming the first example of Ottoman architecture in the Kosovo territory.

"من كان صربياً أو صربي المولد،

أو صربي الدم والمحتد،

ولا يأتي إلى معركة كوسوڤو،

عسى ألا يرى خلفاً يشتاق قلبه إليه،

لا من البنين ولا من البنات!

وعسى ألا ينمو ما تذروه يداه،

لا نبيذ داكن ولا خبر أبيض!

ملعون هو من كل الأزمان إلى كل الأزمان!"

– القيصر لازار يلعن من لم يخرج لقتال الأتراك العثمانيين في معركة كوسوڤو.

اسم المعركة في مختلف اللغات

- الألبانية: Beteja e Kosovës

- العربية: معركة قوصوه أو معركة كوسوفو

- البلغارية: Битка на Косово поле (Bitka na Kosovo pole) أو Косовска битка (Kosovska bitka)

- الكرواتية: Bitka na Kosovu polju أو Kosovska bitka

- Czech: Bitva na Kosově poli

- الهولندية: Slag op het Merelveld

- الإنجليزية: Battle of Amselfeld, Battle of Kossovo أو Battle of Kosovo

- الإستونية:Lahing Kosovo väljal, Kosovo lahing

- الفرنسية: Bataille de Kosovo ou du champ des Merles

- Italian: Battaglia del Kosovo

- الألمانية: Schlacht auf dem Amselfeld

- اليونانية: Μάχη του Κοσσυφοπεδίου (Máchē tou Kossyphopedíou)

- المجرية: Rigómezei csata

- Polish: Bitwa na Kosowym Polu

- Portuguese: Batalha de Kosovo

- الرومانية: Bătălia de la Câmpia Mierlei

- الروسية: Битва на Косовом поле (Bitva na Kosovom pole)

- الصربية: Kosovski Boj أو Boj na Kosovu Polju أو Kosovska bitka

- الصربية سيريلية: Косовски бој أو Бој на Косову Пољу أو Косовска битка

- السلوفاكية: Bitka na Kosovom poli

- السلوڤينية: Bitka na Kosovem polju

- الاسبانية: Batalla de Kosovo

- السويدية: Slaget vid Trastfältet or Slaget vid Kosovo Polje

- التركية: Kosova Savaşı

- بالتركية العثمانية: قوصوه سواشي

انظر أيضاً

- Battle of Dubravnica

- Battle of Pločnik

- Battle of Bileća

- Battle of Kosovo (1448)

- Gazimestan

- لعنة كوسوڤو

- الدولة العثمانية

- الحروب العثمانية في اوروبا

المصادر

- ^ Date: Some sources attempt to give the date as June 28 in the New-Style Gregorian calendar, but that was not adopted until 1582, and did not apply retrospectively (but see Proleptic Gregorian calendar). Moreover, the proleptic Gregorian date of the battle is June 23, not 28. Nevertheless, anniversaries of the battle are still celebrated on June 15 Julian (Vidovdan, that is St. Vitus' Day in the calendar of the Serbian Orthodox Church, which is still Julian), which corresponds to June 28 Gregorian in the 20th and 21st centuries.[بحاجة لمصدر]

- ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between Serbia and the local Albanian majority. The Assembly of Kosovo declared its independence on 17 February 2008, a move that is recognised and the Republic of China (Taiwan), but not by Serbia, which claims it as part of its sovereign territory.

- ^ (Fine 1994, p. 410)

Thus since the Turks also withdrew, one can conclude that the battle was a draw.

- ^ (Emmert 1990, p. ?)

Surprisingly enough, it is not even possible to know with certainty from the extant contemporary material whether one or the other side was victorious on the field. There is certainly little to indicate that it was a great Serbian defeat; and the earliest reports of the conflict suggest, on the contrary, that the Christian forces had won.

- ^ Waley, Daniel; Denley, Peter (2013). Later Medieval Europe: 1250-1520. Routledge. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-317-89018-8.

The outcome of the battle itself was inconclusive.

- ^ Oliver, Ian (2005). War and Peace in the Balkans: The Diplomacy of Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia. I.B.Tauris. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-85043-889-2.

Losses on both sides were appalling and the outcome inconclusive although the Serbs never fully recovered.

- ^ Binns, John (2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-521-66738-8.

The battle is remembered as a heroic defeat, but historical evidence suggests an inconclusive draw.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج (Fine 1994, pp. 409–411)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPetta123 - ^ أ ب Sedlar, Jean W. East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. p. 244.

Nearly the entire Christian fighting force (between 12,000 and 20,000 men) had been present at Kosovo, while the Ottomans (with 27,000 to 30,000 on the battlefield) retained numerous reserves in Anatolia.

- ^ أ ب Cox, John K. The History of Serbia. Greenwood Press. p. 30.

The Ottoman army probably numbered between 30,000 and 40,000. They faced something like 15,000 to 25,000 Christian soldiers.

- ^ أ ب Cowley, Robert. The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin Books. p. 249.

On June 28, 1389, an Ottoman army of between thirty thousand and forty thousand under the command of Sultan Murad I defeated an army of Balkan allies numbering twenty-five thousand to thirty thousand under the command of Prince Lazar of Serbia at Kosovo Polije (Blackbird's Field) in the central Balkans.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Kosovska bitka". Vojna Enciklopedija (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade: Vojnoizdavački zavod. 1972. pp. 659–660.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "ИСТОРИЈА КОЈУ НИСМО УЧИЛИ НА ЧАСОВИМА: Милош Обилић је био турски заточник, али јесте убио Мурата на Косову". www.intermagazin.rs.

- ^ Emmert 1991, p. 3

- ^ Evliya Çelebi; Hazim Šabanović (1996). Putopisi: odlomci o jugoslovenskim zemljama. Sarajevo-Publishing. p. 280. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

Paša Jigit- -beg, koji se prvi put pominje kao jedan između turskih komandanata u kosovskoj bici.

- ^ Slavomir Nastasijevic (1987). Vitezi Kneza Lazara. Narodna Knjiga Beograd. pp. 187–. ISBN 8633100150.

Serbian heavy cavalry took V wedge shape charge position breaking through Ottoman infantry and light cavalry.

- ^ (Emmert 1991, p. ?)[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Emmert 1991, p. 3

- ^ Wayne S. Vucinich, Thomas A. Emmert (1991). Kosovo: Legacy of a Medieval Battle. University of Minnesota. ISBN 9789992287552.

- ^ Sima M. Ćirković (1990). Kosovska bitka u istoriografiji: Redakcioni odbor Sima Ćirković (urednik izdanja) [... et al.]. Zmaj. p. 38. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

Код Мињанелиjа, кнез је претходно заробл - ен и принуЬен да Мурату положи заклетву верности! и тада је један од њих, кажу да је то био Лазар, зарио Мурату мач у прса

- ^ Imber, Colin. The Ottoman Empire: The Structure of Power, 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, p. 85. ISBN 0-230-57451-3.

- ^ Vamik D. Volkan (1998). Bloodlines: From Ethnic Pride to Ethnic Terrorism. Westview Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8133-9038-3.

- ^ Donald Quataert (11 August 2005). The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5.

- ^ History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey By Stanford Jay Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw, p. 24

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 575.

- ^ Isabelle Dierauer (16 May 2013). Disequilibrium, Polarization, and Crisis Model: An International Relations Theory Explaining Conflict. University Press of America. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7618-6106-5.

- ^ Đorđević 1990.

- ^ Manfried Rauchensteiner, Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, 2013, p. 87

وصلات خارجية

- Battle of Kosovo as National Narrative by Dr. Seth Ward

- The Battle of Kosovo: Early Reports of Victory and Defeat by Thomas Emmert

- The Kosovo Legacy by Thomas Emmert alternate URL

- The events Surrounding the Battle of Kosovo 1389 and its cultural effect on the Serbian people by Mark Gottfried

- The Battle of Kosovo Serbian Epic Poems edited by Charles Simic Alternate URL

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from July 2014

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing صربية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2021

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- 1389 في أوروپا

- نزاعات 1389

- معارك الحروب الصربية العثمانية

- معارك الدولة العثمانية

- معارك فرسان الاسبتارية

- الألفية الثانية في كوسوڤو

- القرن 14 في صربيا

- 1389 في الدولة العثمانية

- معارك مملكة البوسنة

- تاريخ كوسوڤو

- معارك صربيا في العصور الوسطى

- معارك الحروب العثمانية المجرية

- قوصوة

- عن إسلام أون لاين.نت