اللغة التركية العثمانية

| التركية العثمانية | |

|---|---|

| لسان عثمانی Lisân-ı Osmânî | |

| |

| المنطقة | الدولة العثمانية-تركيا |

| العرق | Ottoman Turks |

| منقرضة | تحولت إلى التركية المعاصرة في 1928 |

التوركية

| |

الصيغة المبكرة | |

| الأبجدية التركية العثمانية | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في | |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | ota |

| ISO 639-2 | ota |

| ISO 639-3 | ota |

ota | |

| Glottolog | otto1234 |

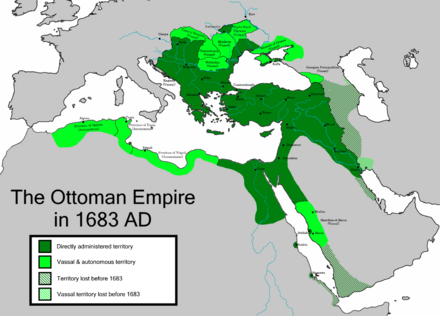

The Ottoman Empire was at its peak, Ottoman Turkish culture including the language also developed in the conquered areas | |

| ثقافة الدولة العثمانية |

|---|

| الفنون البصرية |

| الفنون الأدائية |

| اللغة والأدب |

| الرياضة |

| غيرهم |

اللغة التركية العثمانية (لسانِ عثمانِی) نوع من اللغة التركية التي كانت تستخدم على النحو الإداري واللغة الأدبية للإمبراطورية العثمانية، وهي تتضمن الاقتراض على نطاق واسع من اللغة العربية بالإضافة إلى الفارسية وكتبت بديلا عن الكتابة العربية. وقد تأثّرت اللغة التركية الحديثة إلى حدّ كبير باللغة العثمانية التركية القديمة. Tanzimât era (1839–1876) saw the application of the term "Ottoman" when referring to the language[3] (لسان عثمانی lisân-ı Osmânî or عثمانلیجه Osmanlıca); Modern Turkish uses the same terms when referring to the language of that era (Osmanlıca and Osmanlı Türkçesi). More generically, the Turkish language was called تركچه Türkçe or تركی Türkî "Turkish".

النحو

الحالات

- Nominative and Indefinite accusative/objective: -∅, no suffix. كول göl 'the lake' 'a lake', چوربا çorba 'soup', كیجه gece 'night'; طاوشان گترمش ṭavşan getirmiş 'he/she brought a rabbit'.

- Genitive: suffix ڭ/نڭ –(n)ıñ, –(n)iñ, –(n)uñ, –(n)üñ. پاشانڭ paşanıñ 'of the pasha'; كتابڭ kitabıñ 'of the book'.

- Definite accusative: suffix ی –ı, -i: طاوشانی كترمش ṭavşanı getürmiş 'he/she brought the rabbit'. The variant suffix –u, –ü does not occur in Ottoman Turkish orthography (unlike in Modern Turkish), although it's pronounced with the vowel harmony. Thus, كولی göli 'the lake' vs. Modern Turkish gölü.[4]

- Dative: suffix ه –e: اوه eve 'to the house'.

- Locative: suffix ده –de, –da: مكتبده mektebde 'at school', قفسده ḳafeṣde 'in (the/a) cage', باشده başda 'at a/the start', شهرده şehirde 'in town'. The variant suffix used in Modern Turkish (–te, –ta) does not occur.

- Ablative: suffix دن –den, -dan: ادمدن adamdan 'from the man'.

- Instrumental: suffix or postposition ایله ile. Generally not counted as a grammatical case in modern grammars.

الأفعال

The conjugation for the aorist tense is as follows:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -irim | -iriz |

| 2nd person | -irsiŋ | -irsiŋiz |

| 3rd person | -ir | -irler |

Structure

Ottoman Turkish was highly influenced by Arabic and Persian. Arabic and Persian words in the language accounted for up to 88% of its vocabulary.[5] As in most other Turkic and foreign languages of Islamic communities, the Arabic borrowings were borrowed through Persian, not through direct exposure of Ottoman Turkish to Arabic, a fact that is evidenced by the typically Persian phonological mutation of the words of Arabic origin.[6][7][8]

The conservation of archaic phonological features of the Arabic borrowings furthermore suggests that Arabic-incorporated Persian was absorbed into pre-Ottoman Turkic at an early stage, when the speakers were still located to the north-east of Persia, prior to the westward migration of the Islamic Turkic tribes. An additional argument for this is that Ottoman Turkish shares the Persian character of its Arabic borrowings with other Turkic languages that had even less interaction with Arabic, such as Tatar, Bashkir, and Uyghur. From the early ages of the Ottoman Empire, borrowings from Arabic and Persian were so abundant that original Turkish words were hard to find.[9] In Ottoman, one may find whole passages in Arabic and Persian incorporated into the text.[9] It was however not only extensive loaning of words, but along with them much of the grammatical systems of Persian and Arabic.[9]

In a social and pragmatic sense, there were (at least) three variants of Ottoman Turkish:

- Fasih Türkçe فصیح تورکچه (Eloquent Turkish): the language of poetry and administration, Ottoman Turkish in its strict sense;

- Orta Türkçe اورتا تورکچه (Middle Turkish): the language of higher classes and trade;

- Kaba Türkçe قبا تورکچه (Rough Turkish): the language of lower classes.

A person would use each of the varieties above for different purposes, with the fasih variant being the most heavily suffused with Arabic and Persian words and kaba the least. For example, a scribe would use the Arabic asel (عسل) to refer to honey when writing a document but would use the native Turkish word bal when buying it.

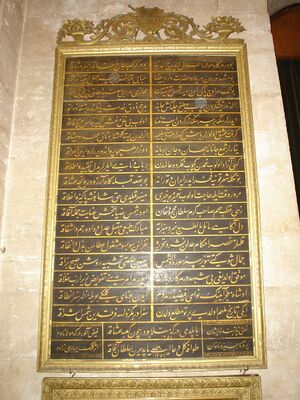

الكتابة

في يوم 8 ديسمبر 2014، وعد الرئيس التركي رجپ طيپ أردغان بجعل تعلم اللغة التركية العثمانية إجبارية على جميع طلاب المدارس في تركيا، كجزء من تأصيل الثقافة التركية، وذلك بالرغم من وجود معارضة قوية للقرار.[10]

History

Historically, Ottoman Turkish was transformed in three eras:

- Eski Osmanlı Türkçesi اسکی عثمانلی تورکچهسی (Old Ottoman Turkish): the version of Ottoman Turkish used until the 16th century. It was almost identical with the Turkish used by Seljuk empire and Anatolian beyliks and was often regarded as part of Eski Anadolu Türkçesi اسکی آناطولی تورکچهسی (Old Anatolian Turkish).

- Orta Osmanlı Türkçesi اورتا عثمانلی تورکچهسی (Middle Ottoman Turkish) or Klasik Osmanlıca (Classical Ottoman Turkish): the language of poetry and administration from the 16th century until Tanzimat.

- Yeni Osmanlı Türkçesi یڭی عثمانلی تورکچهسی (New Ottoman Turkish): the version shaped from the 1850s to the 20th century under the influence of journalism and Western-oriented literature.

Language reform

In 1928, following the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, widespread language reforms (a part in the greater framework of Atatürk's Reforms) instituted by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk saw the replacement of many Persian and Arabic origin loanwords in the language with their Turkish equivalents. One of the main supporters of the reform was the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gökalp.[11] It also saw the replacement of the Perso-Arabic script with the extended Latin alphabet. The changes were meant to encourage the growth of a new variety of written Turkish that more closely reflected the spoken vernacular and to foster a new variety of spoken Turkish that reinforced Turkey's new national identity as being a post-Ottoman state.[بحاجة لمصدر]

See the list of replaced loanwords in Turkish for more examples of Ottoman Turkish words and their modern Turkish counterparts. Two examples of Arabic and two of Persian loanwords are found below.

| English | Ottoman | Modern Turkish |

|---|---|---|

| obligatory | واجب vâcib | zorunlu |

| hardship | مشكل müşkül | güçlük |

| city | شهر şehir | kent (also şehir) |

| province | ولایت vilâyet | il |

| war | حرب harb | savaş |

الحروف

| الحرف | في أول الكلمة | في وسط الكلمة | في اخر الكلمة | الاسم | اللغة التركية | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ا | ا | ا / ـا | ا / ـا | الف | a, â | |

| ء | — | همزة | ||||

| ب | بـ | ـبـ | ـب | بي | b, p | |

| پ | پـ | ـپـ | ـپ | بي | p | |

| ت | تـ | ـتـ | ـت | تي | t | |

| ث | ثـ | ـثـ | ـث | ثي | s | |

| ج | جـ | ـجـ | ـج | جيم | c, ç | |

| چ | چـ | ـچـ | ـچ | çim | ç | |

| ح | حـ | ـحـ | ـح | حا | ḥ | |

| خ | خـ | ـخـ | ـخ | خي | ẖ | |

| د | د | ـد | ـد | دال | d | |

| ذ | ذ | ـذ | ـذ | دال (معجمة) | z | |

| ر | ر | ـر | ـر | ري | r | |

| ز | ز | ـز | ـز | زي | z | |

| ژ | ژ | ـژ | ـژ | جو | j | |

| س | سـ | ـسـ | ـس | سين | s | |

| ش | شـ | ـشـ | ـش | شين | ş | |

| ص | صـ | ـصـ | ـص | صاد | ṣ | |

| ض | ضـ | ـضـ | ـض | ضاد | ż, ḍ | |

| ط | طـ | ـطـ | ـط | طي | ṭ | |

| ظ | ظـ | ـظـ | ـظ | ظي | ẓ | |

| ع | عـ | ـعـ | ـع | عين | ʿ | |

| غ | غـ | ـغـ | ـغ | غين | ġ | |

| ف | فـ | ـفـ | ـف | في | f | |

| ق | قـ | ـقـ | ـق | قاف | ḳ | |

| ك | كـ | ـكـ | ـك | كاف | k, g, ñ | |

| گ | گـ | ـگـ | ـگ | جاف¹ | g | |

| ڭ | ڭـ | ـڭـ | ـڭ | نيف صغير كاف, | ñ | |

| ل | لـ | ـلـ | ـل | لام | l | |

| م | مـ | ـمـ | ـم | ميم | m | |

| ن | نـ | ـنـ | ـن | نون | n | |

| و | و | ـو | ـو | واو | ||

| ه | هـ | ـهـ | ـه | هي | h, e, a | |

| لا | لا | ـلا | ـلا | لامألف | lâ | |

| ى | يـ | ـيـ | ـي | يي | y, ı, i, î | |

الأرقام

الإرث

Historically speaking, Ottoman Turkish is the predecessor of modern Turkish. However, the standard Turkish of today is essentially Türkiye Türkçesi (Turkish of Turkey) as written in the Latin alphabet and with an abundance of neologisms added, which means there are now far fewer loan words from other languages, and Ottoman Turkish was not instantly transformed into the Turkish of today. At first, it was only the script that was changed, and while some households continued to use the Arabic system in private, most of the Turkish population was illiterate at the time, making the switch to the Latin alphabet much easier. Then, loan words were taken out, and new words fitting the growing amount of technology were introduced. Until the 1960s, Ottoman Turkish was at least partially intelligible with the Turkish of that day. One major difference between Ottoman Turkish and modern Turkish is the latter's abandonment of compound word formation according to Arabic and Persian grammar rules. The usage of such phrases still exists in modern Turkish but only to a very limited extent and usually in specialist contexts; for example, the Persian genitive construction takdîr-i ilâhî (which reads literally as "the preordaining of the divine" and translates as "divine dispensation" or "destiny") is used, as opposed to the normative modern Turkish construction, ilâhî takdîr (literally, "divine preordaining").

In 2014, Turkey's Education Council decided that Ottoman Turkish should be taught in Islamic high schools and as an elective in other schools, a decision backed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who said the language should be taught in schools so younger generations do not lose touch with their cultural heritage.[12]

نظام الكتابة

Most Ottoman Turkish was written in the Ottoman Turkish alphabet (تركية عثمانية: الفبا), a variant of the Perso-Arabic script. The Armenian, Greek and Rashi script of Hebrew were sometimes used by Armenians, Greeks and Jews. (See Karamanli Turkish, a dialect of Ottoman written in the Greek script; Armeno-Turkish alphabet)

الأعداد

1 |

١ |

بر |

bir |

2 |

٢ |

ایكی |

iki |

3 |

٣ |

اوچ |

üç |

4 |

٤ |

درت |

dört |

5 |

٥ |

بش |

beş |

6 |

٦ |

آلتی |

altı |

7 |

٧ |

یدی |

yedi |

8 |

٨ |

سكز |

sekiz |

9 |

٩ |

طقوز |

dokuz |

10 |

١٠ |

اون |

on |

11 |

١١ |

اون بر |

on bir |

12 |

١٢ |

اون ایکی |

on iki |

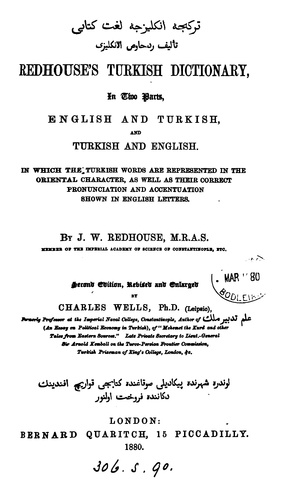

النسخ الحرفي

The transliteration system of the İslâm Ansiklopedisi has become a de facto standard in Oriental studies for the transliteration of Ottoman Turkish texts.[14] In transcription, the New Redhouse, Karl Steuerwald, and Ferit Devellioğlu dictionaries have become standard.[15] Another transliteration system is the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (DMG), which provides a transliteration system for any Turkic language written in Arabic script.[16] There are few differences between the İA and the DMG systems.

| ا | ب | پ | ت | ث | ج | چ | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | ژ | س | ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ف | ق | ك | گ | ڭ | ل | م | ن | و | ه | ی |

| ʾ/ā | b | p | t | s | c | ç | ḥ | ḫ | d | ẕ | r | z | j | s | ş | ṣ | ż | ṭ | ẓ | ʿ | ġ | f | ḳ | k,g,ñ,ğ | g | ñ | l | m | n | v | h | y |

انظر أيضاً

Notes

الهامش

- ^ "5662". DergiPark.

- ^ "Turkey – Language Reform: From Ottoman To Turkish". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Kerslake, Celia (1998). "Ottoman Turkish". In Lars Johanson; Éva Á. Csató (eds.). Turkic Languages. New York: Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 0415082005.

- ^ Redhouse, William James. A Simplified Grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish Language. p. 52.

- ^ Bertold Spuler. Persian Historiography & Geography Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd ISBN 9971774887 p 69

- ^ Percy Ellen Algernon Frederick William Smythe Strangford, Percy Clinton Sydney Smythe Strangford, Emily Anne Beaufort Smythe Strangford, "Original Letters and Papers of the late Viscount Strangford upon Philological and Kindred Subjects", Published by Trübner, 1878. pg 46: "The Arabic words in Turkish have all decidedly come through a Persian channel. I can hardly think of an exception, except in quite late days, when Arabic words have been used in Turkish in a different sense from that borne by them in Persian."

- ^ M. Sukru Hanioglu, "A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire", Published by Princeton University Press, 2008. p. 34: "It employed a predominant Turkish syntax, but was heavily influenced by Persian and (initially through Persian) Arabic.

- ^ Pierre A. MacKay, "The Fountain at Hadji Mustapha", Hesperia, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1967), pp. 193–195: "The immense Arabic contribution to the lexicon of Ottoman Turkish came rather through Persian than directly, and the sound of Arabic words in Persian syntax would be far more familiar to a Turkish ear than correct Arabic".

- ^ أ ب ت Korkut Bugday. An Introduction to Literary Ottoman Routledge, 5 dec. 2014 ISBN 978-1134006557 p XV.

- ^ CEYLAN YEGINSU (2014-12-08). "Turks Feud Over Change in Education". نيويورك تايمز.

- ^ Aytürk, İlker (July 2008). "The First Episode of Language Reform in Republican Turkey: The Language Council from 1926 to 1931". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (in الإنجليزية). 18 (3): 277. doi:10.1017/S1356186308008511. hdl:11693/49487. ISSN 1474-0591. S2CID 162474551.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra (December 9, 2014). "Erdogan's Ottoman language drive faces backlash in Turkey". Reuters. Istanbul. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Hagopian, V. H. (1907). Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar; a practical method of learning the Ottoman-Turkish language. Heidelberg: J. Groos. p. 89. Retrieved 5 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 2

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 13

- ^ Transkriptionskommission der DMG Die Transliteration der arabischen Schrift in ihrer Anwendung auf die Hauptliteratursprachen der islamischen Welt, p. 9 Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 2f.

وصلات خارجية

- Turkish dictionaries at the Open Directory Project

- Turkish language at the Open Directory Project

- Ottoman Text Archive Project

- Ottoman Turkish Language: Resources - University of Michigan

- Ottoman Turkish Language Texts

- Ottoman Romanization Table

- Ottoman Font Rika

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing التركية العثماثية (1500-1928)-language text

- Articles with unnamed Glottolog code

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2019

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Pages with empty portal template

- Ottoman Turkish language

- Languages of Tunisia

- Turkic languages

- Extinct languages of Europe

- لغات منقرضة في آسيا

- اللغة التركية العثمانية