معركة ميسلون

| معركة ميسلون | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من الحرب السورية الفرنسية | |||||||

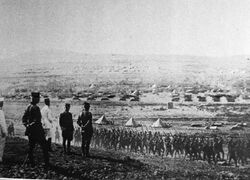

French general Henri Gouraud inspecting his troops in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains the day before the Battle of Maysalun | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

قادة الميليشيات: | ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

|

12,000 جندي (مدهعومين بالدبابات والطائرات) |

1,400–4,000 جندي نظامي فرسان البدو متطوعين مدنيين | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

|

42 قتيل 152 جريح 14 missing (زعم فرنسي)[1] |

~150 قتيل ~1,500 جريح (زعم فرنسي)[1] | ||||||

معركة ميسلون (8 ذي القعدة 1338هـ=24 يوليو 1920م) بين جيش الثورة العربية الكبرى في سوريا، بقيادة الأمير فيصل وصبحي العمري ويوسف العظمة، و الجيش الفرنسي، بقيادة هنري گورو. عدم التكافؤ أدى إلى انتصار الفرنسيين وفتح الباب لفرض الإنتداب الفرنسي على سورية وتقسيمها إلى خمس دويلات.

اجتمع المؤتمر السوري في (16 جمادى الآخرة 1338هـ= 8 مارس 1920م)، واتخذ عدة قرارات تاريخية تنص على إعلان استقلال سوريا بحدودها الطبيعية استقلالا تاما بما فيها فلسطين، ورفض ادعاء الصهيونية في إنشاء وطن قومي لليهود في فلسطين، وإنشاء حكومة مسئولة أمام المؤتمر الذي هو مجلس نيابي، وكان يضم ممثلين انتخبهم الشعب في سوريا ولبنان وفلسطين، وتنصيب الأمير فيصل ملكًا على البلاد. واستقبلت الجماهير المحتشدة في ساحة الشهداء هذه القرارات بكل حماس بالغ وفرحة طاغية باعتبارها محققة لآمالهم ونضالهم من أجل التحرر والاستقلال.

وتشكلت الحكومة برئاسة رضا باشا الركابي، وضمت سبعة من الوزراء من بينهم فارس الخوري وساطع الحصري، ولم يعد فيصل في هذا العهد الجديد المسئول الأول عن السياسة، بل أصبح ذلك منوطًا بوزارة مسئولة أمام المؤتمر السوري، وتشكلت لجنة لوضع الدستور برئاسة هاشم الأتاسي، فوضعت مشروع دستور من 148 مادة على غرار الدساتير العربية، وبدأت الأمور تجري في اتجاه يدعو إلى التفاؤل ويزيد من الثقة.

خلفية

On 30 October 1918, towards the end of World War I, the Sharifian Army led by Emir Faisal, backed by the British Army, captured Damascus from the Ottomans as part of the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire. The war ended less than a month after the Sharifian–British conquest of Damascus. In correspondences between the Sharifian leadership in Mecca and Henry McMahon, the British high commissioner in Cairo, the latter promised to support the establishment of a Sharifian kingdom in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire in return for launching a revolt against the Ottomans.[2] However, the British and French governments secretly made previous arrangements regarding the division of the Ottomans' Arab provinces between themselves in the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement.[3]

To ensure his throne in Syria, Faisal attended the January 1919 Paris Conference, where he was not recognized by the French government as the sovereign ruler of Syria; Faisal called for Syrian sovereignty under his rule,[3] but the European powers attending the conference called for European mandates to be established over the former Arab territories of the Ottoman Empire.[4] In the US-led June 1919 King–Crane Commission, which published its conclusions in 1922, the commission determined that the people of Syria overwhelmingly rejected French rule. Furthermore, Emir Faisal stated to the commission that "French rule would mean certain death to Syrians as a distinguished people".[5]

French forces commanded by General Henri Gouraud landed in Beirut on 18 November 1919, with the ultimate goal of bringing all of Syria under French control. Shortly thereafter, French forces deployed to the Beqaa Valley between Beirut and Damascus. Against King Faisal's wishes, his delegate to General Gouraud, Nuri al-Said, agreed to the French deployment and the disbandment of Arab troops from al-Mu'allaqa, near Zahle. The agreement between al-Said and Gouraud was contrary to an earlier agreement Faisal had made with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, which held that French troops would not deploy in the Beqaa Valley until the League of Nations ruled on the matter. Faisal condemned al-Said and accused of him of treachery. Following the Arab Army withdrawal from al-Mu'allaqa, Christian militiamen from Zahle raided the town, prompting attacks from local Muslim militiamen, which forced several Christian families to the coast. Amid these developments, armed groups of rebels and bandits emerged throughout the Beqaa Valley. When a French officer in Baalbek was assaulted by Shia Muslim rebels opposed to the French presence, Gouraud held the Arab government responsible and demanded that it apologize, which it did not. In response, Gouraud violated his agreement with al-Said and occupied Baalbek. The French deployment along the Syrian coast and the Beqaa Valley provoked unrest throughout Syria and sharpened political divisions between the political camp calling for confronting the French and the camp preferring compromise.[6]

On 8 March 1920, the Syrian National Congress proclaimed the establishment of the Kingdom of Syria, with Faisal as king.[7] This unilateral action was immediately rejected by the British and French.[8] In the San Remo Conference, which was called by the Allied Powers in April 1920, the allocation of mandates in the Arab territories was finalized, with France given a mandate over Syria.[9] France's allocation of Syria was, in turn, repudiated by Faisal and the Syrian National Congress. After months of instability and failure to make good on the promises Faisal had made to the French, General Gouraud gave an ultimatum to Faisal on 14 July 1920 demanding that he disband the Arab Army and submit to French authority by 20 July or face a French military invasion.[10][11] On 18 July, Faisal and the entire cabinet, with the exception of War Minister Yusuf al-Azma, agreed to the ultimatum and issued disbandment orders for the Arab Army units at Anjar, the Beirut–Damascus road and the hills of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains overlooking the Beqaa Valley.[12] Two days later, Faisal informed the French liaison in Damascus of his acceptance of the ultimatum, but for unclear reasons, Faisal's notification did not reach Gouraud until 21 July. Sources suspicious of French intentions accused the French of intentionally delaying delivery of the notice to give Gouraud an official excuse for advancing on Damascus.[13] However, there has been no evidence or indication of French sabotage.[12] News of the disbandment and Faisal's submission led to riots in Damascus on 20 July and their suppression by Emir Zeid, which led to around 200 deaths.[14] Al-Azma, who staunchly opposed surrender, implored Faisal to allow him and the remnants of his army to confront the French.[15]

تمهيد

On 22 July, Faisal dispatched Education Minister Sati al-Husri and the Arab government's former Beirut representative, Jamil al-Ulshi, to meet Gouraud at his headquarters in Aley and persuade him to end his army's advance to Damascus. Gouraud responded by extending the ultimatum by one day and with new, more stringent conditions, namely that France be allowed to establish a mission in Damascus to supervise the implementation of the original ultimatum and the establishment of the French mandate. Al-Husri returned to Damascus the same day to communicate Gouraud's message to Faisal, who called for a meeting of the cabinet on 23 July to consider the new ultimatum. Colonel Cousse, a French liaison officer to Damascus, interrupted the meeting with a demand from Gouraud that the French army be allowed to advance toward Maysalun, where water wells were abundant.[16] Gouraud had originally planned to launch the offensive against Damascus from Ayn al-Judaydah,[17] a spring in the Anti-Lebanon Range,[18] but the lack of water sources there amid the steep, barren mountains led to a change of plans. Accordingly, Gouraud sought to occupy Khan Maysalun,[17] an isolated caravanserai on the Beirut–Damascus road situated at the crest of the Wadi al-Qarn mountain pass in the Anti-Lebanon,[19] located 25 كيلومتر (16 mi) west of Damascus.[17] Gouraud was also motivated to occupy Khan Maysalun because of its proximity to the Hejaz Railway.[20]

Cousse's message confirmed the fears of Faisal's cabinet that Gouraud was intent on taking over Syria by force. The cabinet subsequently rejected Gouraud's ultimatum and issued a largely symbolic appeal to the international community to end the French advance.[16] On 23 July, al-Azma set out from Damascus with his motley force of army regulars and volunteers, which was divided into northern, central and southern columns each headed by camel cavalry units.[21] French forces launched their offensive towards Khan Maysalun and Wadi al-Qarn shortly after dawn on 24 July, at 5:00,[21] while Syrian forces were waiting at their positions overlooking the low end of Wadi al-Qarn.[22]

المقاتلون وتسليحهم

القوات الفرنسية

Estimates of the combined size of the French Army of the Levant forces that participated in the battle ranged from 9,000 to 12,000 troops.[1][14] The troops involved were mostly Senegalese and Algerian,[1] and consisted of ten infantry battalions and a number of cavalry and artillery units.[14] Among the participating units were the 415th Infantry Regiment, the 2nd Algerian Tirailleurs (Riflemen) Regiment, the Senegalese Division, the African Light Infantry Regiment and the Moroccan Spahi Regiment.[23] A number of Maronite volunteers from Mount Lebanon reportedly joined the French forces as well.[24] The Army of the Levant was equipped with field and mountain artillery batteries and 155mm guns,[23] and backed by tanks and fighter bombers.[14] The commander of the French forces was General Mariano Goybet.[23]

القوات السورية

Syrian forces consisted of remnants of the Arab Army assembled by General al-Azma, including soldiers from General Hassan al-Hindi's disbanded Anjar-based garrison, disbanded units from Damascus and Bedouin camel cavalry; most Arab Army units had been disbanded days prior to the battle by order of King Faisal as part of his acceptance of General Gouraud's terms.[12] In addition to Arab Army troops, numerous civilian volunteers and militiamen from Damascus joined al-Azma's forces.[14] Estimates put the number of Syrian soldiers and irregulars at around 4,000,[1] while historian Eliezer Tauber asserts that al-Azma recruited 3,000 soldiers and volunteers, of whom only 1,400 participated in the battle.[25] According to historian Michael Provence, the "quarters of Damascus had been emptied of young men as crowds walked west, some armed only with swords or sticks, to meet the mechanized French column".[26]

Part of the civilian militia units were assembled and led by Yasin Kiwan, a Damascene merchant, Abd al-Qadir Kiwan, the former imam of the Umayyad Mosque, and Shaykh Hamdi al-Juwajani, a Muslim scholar. Yasin and Abd al-Qadir were killed during the battle.[27] Shaykh Muhammad al-Ashmar also participated in the battle with 40–50 of his men from the Midan quarter of Damascus. Other Muslim preachers and scholars from Damascus, including Tawfiq al-Darra (ex-mufti of the Ottoman Fifth Army), Sa'id al-Barhani (preacher at the Tuba Mosque), Muhammad al-Fahl (scholar from the Qalbaqjiyya Madrasa) and Ali Daqqar (preacher at the Sinan Pasha Mosque) also participated in the battle.[28]

The Syrians were equipped with rifles discarded by retreating Ottoman soldiers during World War I and those used by the Sharifian Army's Bedouin cavalry during the 1916 Arab Revolt. The Syrians also possessed a number of machine guns and about 15 artillery pieces. According to various versions, ammunition was low, with 120–250 bullets per rifle, 45 bullets per machine gun, and 50–80 shells per cannon. Part of this ammunition was also unusable because many bullet and rifle types did not correspond to each other.[11]

مؤتمر سان ريمو

مقالة مفصلة: مؤتمر سان ريمو

مقالة مفصلة: مؤتمر سان ريمو

غير أن هذه الخطوة الإصلاحية في تاريخ البلاد لم تجد قبولا واستحسانًا من الحلفاء، ورفضت الحكومتان: البريطانية والفرنسية قرارات المؤتمر في دمشق، واعتبرت فيصل أميرًا هاشميًا لا يزال يدير البلاد بصفته قائدًا للجيوش الحليفة لا ملكًا على دولة. ودعته إلى السفر إلى أوروبا لعرض قضية بلاده؛ لأن تقرير مصير الأجزاء العربية لا يزال بيد مؤتمر السلم.

وجاءت قرارات مؤتمر السلم المنعقد في "سان ريمو" الإيطالية في (6 شعبان 1338هـ= 25 إبريل 1920م) مخيبة لآمال العرب؛ فقد قرر الحلفاء استقلال سوريا تحت الانتداب الفرنسي، واستقلال العراق تحت الانتداب البريطاني، ووضع فلسطين تحت الانتداب البريطاني، وكان ذلك سعيًا لتحقيق وعد بلفور لليهود فيها. ولم يكن قرار الانتداب في سان ريمو إلا تطبيقًا لإتفاقية سايكس ـ بيكو المشهورة، وإصرارا قويا من فرنسا على احتلال سوريا.

وكان قرار المؤتمر ضربة شديدة لآمال الشعب في استقلال سوريا ووحدتها، فقامت المظاهرات والاحتجاجات، واشتعلت النفوس بالثورة، وأجمع الناس على رفض ما جاء بالمؤتمر من قرارات، وكثرت الاجتماعات بين زعماء الأمة والملك فيصل، وأبلغوه تصميم الشعب على مقاومة كل اعتداء على حدود البلاد واستقلالها.

رفض فيصل قرارات المؤتمر

وتحت تأثير الضغط الوطني وازدياد السخط الشعبي، رفض فيصل بدوره قرارات مؤتمر سان ريمو، وبعث إلى بريطانيا وفرنسا برفضه هذا؛ لأن هذه القرارات جاءت مخالفة لأماني الشعب في الوحدة السورية والاستقلال، ولفصلها فلسطين عن سوريا، ورفض الذهاب إلى أوروبا لعرض قضية بلاده أمام مؤتمر السلم ما لم تتحقق شروطه في الاعتراف باستقلال سوريا بما فيها فلسطين، ودارت مراسلات كثيرة بينه وبين الدولتين بخصوص هذا الشأن، لمحاولة الخروج من المأزق الصعب الذي وضعته فيه قرارات مؤتمر سان ريمو، غير أن محاولاته تكسرت أمام إصرار الدولتين على تطبيق ما جاء في المؤتمر.

وفي أثناء ذلك تشكلت حكومة جديدة برئاسة هاشم الأتاسي في (14 شعبان 1338هـ= 3 مايو 1920م) ودخلها وزيران جديدان من أشد الناس مطالبة بالمقاومة ضد الاحتلال، هما: يوسف العظمة، وعبد الرحمن الشهبندر، وقدمت الوزارة الجديدة بيانها الذي تضمن تأييد الاستقلال التام، والمطالبة بوحدة سوريا بحدودها الطبيعة، ورفض كل تدخل يمس السيادة القومية. واتخذت الوزارة إجراءات دفاعية لحماية البلاد، ووسعت نطاق التجنيد بين أبناء الشعب استعدادًا للدفاع عن الوطن.

الإنذار الفرنسي

كان من نتيجة إصرار القوى الوطنية السورية على رفض قرارات مؤتمر سان ريمو أن اتخذت فرنسا قرارًا بإعداد حملة عسكرية وإرسالها إلى بيروت؛ استعدادًا لبسط حكمها على سوريا الداخلية مهما كلفها الأمر، وساعدها على الإقدام أنها ضمنت عدم معارضة الحكومة البريطانية على أعمالها في سوريا، وكانت أخبار الحشود العسكرية على حدود المنطقة الشرقية في زحلة وقرب حلب تتوالى، ثم لم يلبث أن وجه الجنرال "گورو" قائد الحملة الفرنسية الإنذار الشهير إلى الحكومة العربية بدمشق في (27 شوال 1338 هـ= 14 يوليو 1920م) يطلب فيه: قبول الانتداب الفرنسي، وتسريح الجيش السوري، والموافقة على احتلال القوات الفرنسية لمحطات سكك الحديد في رياق وحمص وحلب وحماه.

وطلب الجنرال قبول هذه الشروط جملة أو رفضها جملة، وحدد مهلة لإنذاره تنتهي بعد أربعة أيام، فإذا قبل فيصل بهذه الشروط فعليه أن ينتهي من تنفيذها كلها قبل (15 ذي القعدة 1338هـ= 31 يوليو 1920م) عند منتصف الليل، وإذا لم يقبل فإن العاقبة لن تقع على فرنسا، وتتحمل حكومة دمشق مسئولية ما سيقع عليها.

ولما سمع الناس بخبر هذا الإنذار، اشتعلت حماستهم وتفجرت غضبًا، وأقبلوا على التطوع، فامتلأت بهم الثكنات العسكرية، واشتد إقبال الناس على شراء الأسلحة والذخائر، وأسرعت الأحياء في تنظيم قوات محلية للحفاظ على الأمن.

قبول فيصل بالإنذار

اجتمع الملك فيصل بمجلس الوزراء في (29 شوال 1338 هـ= 16 يوليو 1920م) لبحث الإنذار، ووضع الخطة الواجب اتباعها قبل انقضاء مهلته، وكان رأي يوسف العظمة وزير الدفاع أنه يوجد لدى الجيش من العتاد والذخيرة ما يمكنه من مقاومة الفرنسيين لكنها لم تكن كافية للصمود طويلا أمام الجيش الفرنسي البالغ العدد والعتاد، واتجه رأي الأغلبية عدا العظمة إلى قبول الإنذار الفرنسي، وبقي أمام فيصل أخذ موافقة أعضاء المؤتمر السوري على قبول الإنذار؛ فاجتمع بهم في قصره، لكن الاجتماع لم يصل إلى قرار، فاجتمع الملك فيصل مع مجلس وزرائه ثانية وأعلنوا جميعًا قبولهم الإنذار، وبدأت الحكومة في تسريح الجيش دون خطة أو نظام، فخرج الجنود من ثكناتهم بعد أن تلقوا الأوامر بتسريحهم ومعهم أسلحتهم، واختلطوا بالجماهير المحتشدة الغاضبة من قبول الحكومة بالإنذار، فاشتدت المظاهرات وعلت صياحات الجماهير، وعجزت الشرطة عن الإمساك بزمام الأمور.

معركة ميسلون

وفي ظل هذه الأجواء المضطربة وصلت الأخبار إلى دمشق بتقدم الجيش الفرنسي، بقيادة گورو في (5 ذي القعدة 1338 هـ= 21 يوليو 1920م) نحو دمشق بعد انسحاب الجيش العربي، محتجًا بأن البرقية التي أرسلها فيصل بقبوله الإنذار لم تصل بسبب انقطاع أسلاك البرق من قبل العصابات السورية، وإزاء هذه الأحداث وافق الملك فيصل على وقف تسريح الجيش، وأعيدت القوات المنسحبة إلى مراكز جديدة مقابل الجيش الفرنسي، وأرسل إلى غورو يطلب منه أن يوقف جيشه حتى يرسل له مندوبًا للتفاهم معه حقنًا للدماء، لكن هذه المحاولة فشلت في إقناع الجنرال المغرور الذي قدم شروطًا جديدة تمتهن الكرامة العربية والشرف الوطني حتى يبقى الجيش الفرنسي في مكانه دون تقدم، وكان من بين هذه الشروط تسليم الجنود المسرّحين أسلحتهم إلى المستودعات، وينزع السلاح من الأهالي.

رفضت الوزارة شروط غورو الجديدة، وتقدم يوسف العظمة لقيادة الجيش السوري دفاعًا عن الوطن، في الوقت الذي زحف فيه الجيش الفرنسي نحو خان ميسلون بحجة توفر الماء في المنطقة، وارتباطها بالسكك الحديدية بطريق صالح للعجلات، وأصبح على قرب 25 كم من دمشق.

وفي هذه الأثناء كانت المظاهرات لا تزال تملأ دمشق تنادي بإعلان الجهاد ضد الفرنسيين، وأصدر فيصل منشورا يحض الناس على الدفاع بعد أن فشلت كل المحاولات لإقناع الفرنسي عن التوقف بجيشه.

خرج يوسف العظمة بحوالي 4000 جندي يتبعهم مثلهم أو أقل قليلا من المتطوعين إلى ميسلون، ولم تضم قواته دبابات أو طائرات أو تجهيزات ثقيلة، واشتبك مع القوات الفرنسية في صباح يوم (8 ذي القعدة 1338 هـ/24 يوليو 1920م) في معركة غير متكافئة، دامت ساعات، اشتركت فيها الطائرات الفرنسية والدبابات والمدافع الثقيلة.

وتمكن الفرنسيون من تحقيق النصر؛ نظرًا لكثرة عددهم وقوة تسليحهم، وفشلت الخطة التي وضعها العظمة، فلم تنفجر الألغام التي وضعها لتعطيل زحف القوات الفرنسية، وتأخرت عملية مباغتة الفرنسيين، ونفدت ذخائر الأسلحة.

وعلى الرغم من ذلك فقد استبسل المجاهدون في الدفاع واستشهد العظمة في معركة الكرامة التي كانت نتيجتها متوقعة خاضها دفاعًا عن شرفه العسكري وشرف بلاده، فانتهت حياته وحياة الدولة التي تولى الدفاع عنها.

ولم يبق أمام الجيش الفرنسي ما يحول دون احتلال دمشق في اليوم نفسه، لكنه القائد المعجب بنصره آثر أن يدخل دمشق في اليوم الثاني محيطًا نفسه بأكاليل النصر وسط جنوده وحشوده.

The first clashes took place at 6:30 when French tanks stormed the central position of the Syrian defensive line while French cavalry and infantry units assaulted the Syrians' northern and southern positions.[16] The camel cavalry were the first Syrian units to engage the French.[21] Syrian forces initially put up stiff resistance along the front,[21][29] but lacked coordination between their different units.[21] Early in the clashes, Syrian artillery fire inflicted casualties on a battery of French soldiers.[22] French tanks faced heavy fire as they attempted to gain ground against the Syrians.[22] However, French artillery took a toll on Syrian forces and by 8:30 the French had broken the Syrians' central trench.[21] At one point in the first few hours of the clashes,[29] Syrian forces managed to briefly pin down two Senegalese companies that were relatively isolated on the French right flank.[22] The losses inflicted on the two Senegalese units represented roughly half of the French army's total casualties.[22] Nonetheless, by 10:00, the battle was effectively over, having turned decisively in favor of the French.[29]

At 10:30, French forces reached al-Azma's headquarters, unhindered by the mines laid en route by the Syrians.[21] Little information is known about the battle from the Syrian side.[22] According to one version, when French forces were about 100 meters in the distance, al-Azma rushed to a Syrian artilleryman stationed near him and ordered him to open fire. However, before any shells could be fired, a French tank unit spotted al-Azma and gunned him down by machine gun.[21] In another account, al-Azma had attempted to mine the trenches as the French forces approached his position, but was shot down by the French before he could set off the charges.[29] Al-Azma's death marked the end of the battle, although intermittent clashes continued until 13:30.[21] Surviving Syrian fighters were bombed from the air and harried by the French as they retreated toward Damascus.[29]

After the battle, General Gouraud addressed General Goybet as follows:

GENERAL ORDER No. 22

Aley, 24 July 1920

- "The General is deeply happy to address his congratulations to General Goybet and his valiant troops: 415th of line, 2nd Algerian sharpshooters, 11th and 10th Senegalese sharpshooters, light-infantry-men of Africa, Moroccan trooper regiment, batteries of African groups, batteries of 155, 314, company of tanks, bombardment groups and squadrons who in the hard fight of 24 of July, have broken the resistance of the enemy who defied us for 8 months ... They have engraved a glorious page in the history of our country." – General Gouraud

الأعقاب

Initial estimates of the casualties which claimed 2,000 Syrian dead and 800 French casualties turned out to be exaggerated.[21] The French Army claimed 42 of its soldiers were killed, 152 wounded and 14 missing in action, while around 150 Syrian fighters were killed and 1,500 wounded.[1] King Faisal observed the battle unfold from the village of al-Hamah, and as it became apparent that the Syrians had been routed, he and his cabinet, with the exception of Interior Minister Ala al-Din al-Durubi, who had quietly secured a deal with the French, departed for al-Kiswah, a town located at the southern approaches of Damascus.[29]

French forces had captured Aleppo on 23 July without a fight,[29] and after their victory at Maysalun, French troops besieged and captured Damascus on 25 July. Within a short time, the majority of Faisal's forces fled or surrendered to the French, although parties of Arab groups opposed to French rule continued to resist before being quickly defeated.[11] King Faisal returned to Damascus on 25 July and asked al-Durubi to form a government, although al-Durubi had already decided on the composition of his cabinet, which was confirmed by the French. General Gouraud condemned Faisal's rule in Syria, accusing him of having "dragged the country to within an inch of destruction", and stating that because of this, it was "utterly impossible for him to remain in the country".[30] Faisal denounced Gouraud's statement and insisted that he remained the sovereign head of Syria whose authority he was "granted by the Syrian people".[30]

Although he verbally dismissed the French order expelling him and his family from Syria, Faisal departed Damascus on 27 July with only one of his cabinet members, al-Husri.[30] He initially traveled south to Daraa in the Hauran region where he gained the allegiance of local tribal leaders.[31] However, a French ultimatum to the tribal leaders to expel Faisal or face the bombardment of their encampments compelled Faisal to head west to Haifa in British-held Palestine on 1 August and avoid further bloodshed. Faisal's departure from Syria marked an end to his goal of establishing and leading an Arab state in Syria.[32]

الذكرى

The French took control of the territory that became the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon. France divided Syria into smaller statelets centered on certain regions and sects, including Greater Lebanon for the Maronites, Jabal al-Druze State for the Druze in Hauran, the Alawite State for the Alawites in the Syrian coastal mountains and the states of Damascus and Aleppo.[33] Gouraud reportedly went to the tomb of Saladin, kicked it, and said:[34]

Awake, Saladin. We have returned. My presence here consecrates the victory of the Cross over the Crescent.

Although the Syrians were decisively defeated, the Battle of Maysalun "has gone down in Arab history as a synonym for heroism and hopeless courage against huge odds, as well as for treachery and betrayal", according to Iraqi historian Ali al-Allawi.[29] According to British journalist Robert Fisk, the Battle of Maysalun was "a struggle which every Syrian learns at school but about which almost every Westerner is ignorant".[35] Historian Tareq Y. Ismael wrote that following the battle, the "Syrian resistance at Khan Maysalun soon took on epic proportions. It was viewed as an Arab attempt to stop the imperial avalanche." He also states that the Syrians' defeat caused popular attitudes in the Arab world that exist until the present day which hold that the Western world dishonors the commitments it makes to the Arab people and "oppresses anyone who stands in the way of its imperial designs."[36] Sati' al-Husri, a major pan-Arabist thinker, asserted that the battle was "one of the most important events in the modern history of the Arab nation."[37] The event is annually commemorated by Syrians, during which thousands visit the grave of al-Azma in Maysalun.[37]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Khoury 1987, p. 97.

- ^ Allawi 2014, pp. 60–61.

- ^ أ ب Moubayed 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Moubayed 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Moubayed 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Allawi, 2014, p. 285.

- ^ Baker 1979, p. 161.

- ^ Baker 1979, p. 162.

- ^ Baker 1979, p. 163.

- ^ Moubayed 2006, p. 44.

- ^ أ ب ت Tauber 1995, p. 215.

- ^ أ ب ت Allawi 2014, p. 288.

- ^ Tauber 2013, p. 34.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Allawi 2014, p. 289.

- ^ Moubayed 2006, p. 45.

- ^ أ ب ت Allawi 2014, p. 290.

- ^ أ ب ت Russell 1985, p. 187.

- ^ Russel 1985, p. 186.

- ^ Rogan, Eugene (2009). The Arabs: A History. Basic Books. p. 163. ISBN 9780465025046.

- ^ Russel 1985, p. 246.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Tauber 1995, p. 218.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Russell 1985, p. 189.

- ^ أ ب ت Husri 1966, p. 172.

- ^ Salibi, Kamal S. (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I. B. Tauris. p. 33. ISBN 9781860649127.

- ^ Tauber 1995, p. 216.

- ^ Provence 2011, p. 218.

- ^ Gelvin 1998, p. 115.

- ^ Gelvin 1998, pp. 115–116.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Allawi 2014, p. 291.

- ^ أ ب ت Allawi 2014, p. 292.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 293.

- ^ Allawi 2014, p. 294.

- ^ McHugo 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Meyer, Karl Ernest; Brysac, Shareen Blair (2008). Kingmakers: The Invention of the Modern Middle East. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 359. ISBN 9780393061994.

Awake, Saladin. We have returned.

- ^ Fisk 2007, p. 1003.

- ^ Ismael 2014, p. 57.

- ^ أ ب Sorek 2015, p. 32.

مصادر الدراسة

- خيرية قاسم: الحكومة العربية في دمشق ـ دار المعارف ـ القاهرة ـ 1971م.

- جلال يحيى: العالم العربي الحديث ـ دار المعارف ـ القاهرة ـ 1985م.

- على سلطان: تاريخ سورية (حكم فيصل بن حسين) ـ دار طلاس ـ دمشق ـ 1987م.

- صلاح العقاد: المشرق العربي المعاصر ـ مكتبة الأنجلو المصرية ـ القاهرة ـ 1979.

إسلام أون لاين: ميسلون تصريح 33°35′44″N 36°3′53″E / 33.59556°N 36.06472°E