كرناتكا

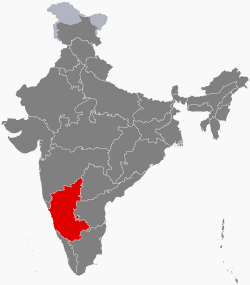

كـَرناتـَكا (بالكنادا: ಕರ್ನಾಟಕ, تـُنطـَق [kəɾˈnɑːʈəkɑː]) تعتبر ثامن ولاية هندية من حيث المساحة حيث تبلغ مساحتها 192،000 كم2 والمرتبة التاسعة من حيث عدد السكان حيث يبلغ عدد سكانها 55،868،200 نسمة عاصمتها مدينة بنگالور.

كارناتاكا ولاية تقع على الساحل الغربي في الجزء الجنوبي للهند وتبلغ مساحتها 191,791كم² وسكانها 44,817,398 نسمة وعاصمتها بانغالور، ويمثل الهندوس 80% من سكان الولاية والمسلمون 10% والمسيحيون 3% وتبلغ الأمية فيها نحو 60%. ويعتمد اقتصاد الولاية على زراعة البن والأخشاب، وصناعة الطائرات والأجهزة الكهربائية وصناعة النسيج، وتعدين الحديد والنحاس والذهب والمنجنيز والميكا.

Karnataka is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, Goa to the northwest, Maharashtra to the north, Telangana to the northeast, Andhra Pradesh to the east, Tamil Nadu to the southeast, and Kerala to the south. It is the only southern state to have land borders with all of the other 4 southern Indian sister states. The state covers an area of 191,976 square kilometres (74,122 sq mi), or 5.83 percent of the total geographical area of India. It is the sixth largest Indian state by area. With 61,130,704 inhabitants at the 2011 census, Karnataka is the eighth largest state by population, comprising 31 districts. Kannada, one of the classical languages of India, is the most widely spoken and official language of the state. Other minority languages spoken include Urdu, Konkani, Marathi, Tulu, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kodava and Beary. Karnataka also contains some of the only villages in India where Sanskrit is primarily spoken.[11][12][13]

Though several etymologies have been suggested for the name Karnataka, the generally accepted one is that Karnataka is derived from the Kannada words karu and nādu, meaning "elevated land". Karu Nadu may also be read as karu, meaning "black" and nadu, meaning "region", as a reference to the black cotton soil found in the Bayalu Seeme region of the state. The British used the word Carnatic, sometimes Karnatak, to describe both sides of peninsular India, south of the Krishna.[14]

With an antiquity that dates to the paleolithic, Karnataka has been home to some of the most powerful empires of ancient and medieval India. The philosophers and musical bards patronised by these empires launched socio-religious and literary movements which have endured to the present day. Karnataka has contributed significantly to both forms of Indian classical music, the Carnatic and Hindustani traditions.

The economy of Karnataka is the Sixth-largest of any Indian state with ₹16٫39 trillion (210 بليون US$) in gross domestic product and a per capita GDP of ₹231٬000 (US$2٬900).[4][3] Karnataka has the nineteenth highest ranking among Indian states in Human Development Index.[10]

التاريخ

Karnataka's pre-history goes back to a paleolithic hand-axe culture evidenced by discoveries of, among other things, hand axes and cleavers in the region.[15] Evidence of neolithic and megalithic cultures have also been found in the state. Gold discovered in Harappa was found to be imported from mines in Karnataka, prompting scholars to hypothesise about contacts between ancient Karnataka and the Indus Valley Civilisation ca. 3300 BCE.[16][17]

Mallikarjuna temple and Kashi Vishwanatha temple في Pattadakal, شمال كرناتكا built successively by Chalukya Empire وRashtrakuta Empire هم موقع تراث عالمي لليونسكو.

امبراطورية هويسالا sculptural articulation في بلور.

تمثال Ugranarasimha في هامپي (موقع تراث عالمي)، يقع ضمن أطلال ڤيجايانگرا، العاصمة السابقة لـامبراطورية ڤيجايانگرا.

Prior to the third century BCE, most of Karnataka formed part of the Nanda Empire before coming under the Mauryan empire of Emperor Ashoka. Four centuries of Satavahana rule followed, allowing them to control large areas of Karnataka. The decline of Satavahana power led to the rise of the earliest native kingdoms, the Kadambas and the Western Gangas, marking the region's emergence as an independent political entity. The Kadamba Dynasty, founded by Mayurasharma, had its capital at Banavasi;[18][19] the Western Ganga Dynasty was formed with Talakad as its capital.[20][21]

These were also the first kingdoms to use Kannada in administration, as evidenced by the Halmidi inscription and a fifth-century copper coin discovered at Banavasi.[22][23] These dynasties were followed by imperial Kannada empires such as the Badami Chalukyas,[24][25] the Rashtrakuta Empire of Manyakheta[26][27] and the Western Chalukya Empire,[28][29] which ruled over large parts of the Deccan and had their capitals in what is now Karnataka. The Western Chalukyas patronised a unique style of architecture and Kannada literature which became a precursor to the Hoysala art of the 12th century.[30][31] Parts of modern-day Southern Karnataka (Gangavadi) were occupied by the Chola Empire at the turn of the 11th century.[32] The Cholas and the Hoysalas fought over the region in the early 12th century before it eventually came under Hoysala rule.[32]

At the turn of the first millennium, the Hoysalas gained power in the region. Literature flourished during this time, which led to the emergence of distinctive Kannada literary metres, and the construction of temples and sculptures adhering to the Vesara style of architecture.[33][34][35][36] The expansion of the Hoysala Empire brought minor parts of modern Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu under its rule. In the early 14th century, Harihara and Bukka Raya established the Vijayanagara empire with its capital, Hosapattana (later named Vijayanagara), on the banks of the Tungabhadra River in the modern Bellary district. The empire rose as a bulwark against Muslim advances into South India, which it completely controlled for over two centuries.[37][38]

In 1565, Karnataka and the rest of South India experienced a major geopolitical shift when the Vijayanagara empire fell to a confederation of Islamic sultanates in the Battle of Talikota.[39] The Bijapur Sultanate, which had risen after the demise of the Bahmani Sultanate of Bidar, soon took control of the Deccan; it was defeated by the Moghuls in the late 17th century.[40][41] The Bahmani and Bijapur rulers encouraged Urdu and Persian literature and Indo-Saracenic architecture, the Gol Gumbaz being one of the high points of this style.[42] During the sixteenth century, Konkani Hindus migrated to Karnataka, mostly from Salcette, Goa,[43] while during the seventeenth and eighteenth century, Goan Catholics migrated to North Canara and South Canara, especially from Bardes, Goa, as a result of food shortages, epidemics and heavy taxation imposed by the Portuguese.[44]

In the period that followed, parts of northern Karnataka were ruled by the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Maratha Empire, the British, and other powers.[45] In the south, the Mysore Kingdom, a former vassal of the Vijayanagara Empire, was briefly independent.[46] With the death of Krishnaraja Wodeyar II, Haidar Ali, the commander-in-chief of the Mysore army, gained control of the region. After his death, the kingdom was inherited by his son Tipu Sultan.[47] To contain European expansion in South India, Haidar Ali and later Tipu Sultan fought four significant Anglo-Mysore Wars, the last of which resulted in Tippu Sultan's death and the incorporation of Mysore into the British Raj in 1799.[48] The Kingdom of Mysore was restored to the Wodeyars and Mysore remained a princely state under the British Raj.

Chief Minister Dr. Devaraj Urs يعلن الاسم الجديد لولاية ميسور: 'كرناتكا' |

As the "doctrine of lapse" gave way to dissent and resistance from princely states across the country, Kittur Chennamma, Sangolli Rayanna and others spearheaded rebellions in Karnataka in 1830, nearly three decades before the Indian Rebellion of 1857. However, Kitturu was taken over by the British East India Company even before the doctrine was officially articulated by Lord Dalhousie in 1848.[49] Other uprisings followed, such as the ones at Supa, Bagalkot, Shorapur, Nargund and Dandeli. These rebellions—which coincided with the Indian Rebellion of 1857—were led by Mundargi Bhimarao, Bhaskar Rao Bhave, the Halagali Bedas, Raja Venkatappa Nayaka and others. By the late 19th century, the independence movement had gained momentum; Karnad Sadashiva Rao, Aluru Venkata Raya, S. Nijalingappa, Kengal Hanumanthaiah, Nittoor Srinivasa Rau and others carried on the struggle into the early 20th century.[50]

After India's independence, the Maharaja, Jayachamarajendra Wodeyar, allowed his kingdom's accession to India. In 1950, Mysore became an Indian state of the same name; the former Maharaja served as its Rajpramukh (head of state) until 1975. Following the long-standing demand of the Ekikarana Movement, Kodagu- and Kannada-speaking regions from the adjoining states of Madras, Hyderabad and Bombay were incorporated into the Mysore state, under the States Reorganisation Act of 1956. The thus expanded state was renamed Karnataka, seventeen years later, on 1 November 1973.[51] In the early 1900s through the post-independence era, industrial visionaries such as Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvarayya, born in Muddenahalli, Chikballapur district, played an important role in the development of Karnataka's strong manufacturing and industrial base.

الجغرافيا

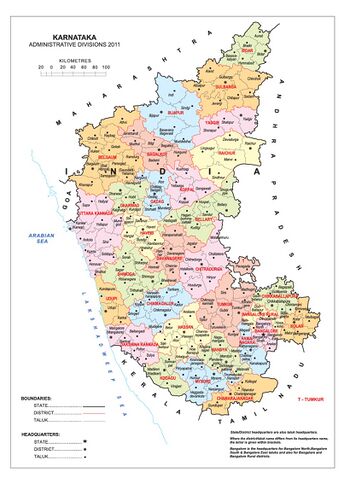

التقسيمات

There are 31 districts in Karnataka. Each district (zila) is governed by a district commissioner (ziladar). The districts are further divided into sub-districts (talukas), which are governed by sub-commissioners (talukdars); sub-divisions comprise blocks (tehsils/hobli), which are governed by block development officers (tehsildars), which contain village councils (panchayats), town municipal councils (purasabhe), city municipal councils (nagarasabhe), and city municipal corporations (mahanagara palike).

| Sl. no. | التقسيمات | العاصمة | Sl. no. | الأضلع | العاصمة | الخريطة |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belagavi | Belagavi | 1 | Bagalkote | Bagalkote | |

| 2 | Belagavi | Belagavi | ||||

| 3 | Dharwad | Dharwad | ||||

| 4 | Gadag | Gadag-Betagiri | ||||

| 5 | Haveri | Haveri | ||||

| 6 | Uttara Kannada | Karwar | ||||

| 7 | ڤيجاياپورا | ڤيجاياپورا | ||||

| 2 | بنگالورو | بنگالورو | 8 | Bengaluru Urban | بنگالورو | |

| 9 | ريف بنگالورو | بنگالورو | ||||

| 10 | Chikkaballapura | Chikkaballapura | ||||

| 11 | Chitradurga | Chitradurga | ||||

| 12 | Davanagere | Davanagere | ||||

| 13 | Kolar | كولار | ||||

| 14 | Ramanagara | رامانگرا | ||||

| 15 | Shivamogga | Shivamogga | ||||

| 16 | Tumakuru | توماكورو | ||||

| 3 | Kalabuargi | Kalabuargi | 17 | Ballari | Ballari | |

| 18 | Bidar | بيدار | ||||

| 19 | Kalabuargi | Kalabuargi | ||||

| 20 | Koppal | Koppal | ||||

| 21 | Raichur | Raichur | ||||

| 22 | Yadagiri | Yadagiri | ||||

| 23 | Vijayanagara | Hosapete | ||||

| 4 | ميسورو | ميسورو | 24 | Chamarajanagara | Chamarajanagara | |

| 25 | Chikkamagaluru | Chikkamagaluru | ||||

| 26 | Dakshina Kannada | Mangaluru | ||||

| 27 | حسن | حسن | ||||

| 28 | Kodagu | Madikeri | ||||

| 29 | مانديا | مانديا | ||||

| 30 | ميسورو | ميسورو | ||||

| 31 | أودوپي | أودوپي |

الديمغرافيا

| الترتيب | المدينة | الضلع | التعداد (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | بنگالورو | حضر بنگالورو و ريف بنگالورو | 10,456,000 |

| 2 | Hubli–Dharwad | Dharwad | 943,857 |

| 3 | ميسور | ميسور | 920,550 |

| 4 | Belgaum | Belgaum | 610,350 |

| 5 | Gulbarga | Gulbarga | 543,147 |

| 6 | منگالور | Dakshina Kannada | 484,785 |

| 7 | Davanagere | Davanagere | 435,128 |

| 8 | Bellary | Bellary | 409,444 |

| 9 | بيجاپور | بيجاپور | 330,143 |

| 10 | شيموگا | شيموگا | 322,650 |

| 11 | تومكور | تومكور | 305,821 |

According to the 2011 census of India,[52] the total population of Karnataka was 61,095,297 of which 30,966,657 (50.7%) were male and 30,128,640 (49.3%) were female, or 1000 males for every 973 females. This represents a 15.60% increase over the population in 2001. The population density was 319 per km2 and 38.67% of the people lived in urban areas. The literacy rate was 75.36% with 82.47% of males and 68.08% of females being literate. 84.00% of the population were Hindu, 12.92% were Muslim, 1.87% were Christian, 0.72% were Jains, 0.16% were Buddhist, 0.05% were Sikh and 0.02% were belonging to other religions and 0.27% of the population did not state their religion.[53]

In 2007 the state had a birth rate of 2.2%, a death rate of 0.7%, an infant mortality rate of 5.5% and a maternal mortality rate of 0.2%. The total fertility rate was 2.2.[54]

In the field of speciality health care, Karnataka's private sector competes with the best in the world.[55] Karnataka has also established a modicum of public health services having a better record of health care and child care than most other states of India. In spite of these advances, some parts of the state still leave much to be desired when it comes to primary health care.[56]

الحكومة والادارة

الديانات

اختار أدي شانكارا سرينگري في كرناتكا لتأسيس أول ماثاته الأربعة. Ramanujacharya, the leading expounder of Viśiṣṭādvaita, spent many years in Melkote. He came to Karnataka in 1098 AD and lived here until 1122 AD. He first lived in Tondanur and then moved to Melkote where the Cheluvanarayana Temple and a well organised Matha were built. He was patronized by the Hoysala king, Vishnuvardhana.[57] In the twelfth century, Veerashaivism emerged in northern Karnataka as a protest against the rigidity of the prevailing social and caste system. Leading figures of this movement were Basava, Akka Mahadevi and Allama Prabhu, who established the Anubhava Mantapa where the philosophy of Shakti Vishishtadvaita was expounded. This was the basis of the Lingayat faith which today counts millions among its followers.[58] The Jain philosophy and literature have contributed immensely to the religious and cultural landscape of Karnataka.

الإسلام، الذي كان له حضور مبكر على الساحل الغربي للهند منذ القرن العاشر، اكتسب موطئ قدم في كرناتكا بصعود سلطنتي بهماني وبيجاپور اللتين حكمتا أجزاء من كرناتكا.[59] وصلت المسيحية كرناتكا في القرن 16 مع البرتغاليين والقديس فرانسس زاڤيير في 1545.[60] وقد كان للبوذية شعبية في كرناتكا في الألفية الأولى في أماكن مثل Gulbarga and Banavasi. A chance discovery of edicts and several Mauryan relics at Sannati في Gulbarga district في 1986 أثبتت أن حوض نهر كرشنا كان يوماً ما معقلاً لبوذية مهايانا و هينايانا.

Mysore Dasara is celebrated as the Nada habba (state festival) and this is marked by major festivities at Mysore.[61] Ugadi (Kannada New Year), Makara Sankranti (the harvest festival), Ganesh Chaturthi, Nagapanchami, Basava Jayanthi, Deepavali, ورمضان هي الأعياد الكبرى الاخرى في كرناتكا.

السياحة

|

الهامش

- ^ "Protected Areas of India: State-wise break up of Wildlife Sanctuaries" (PDF). Wildlife Institute of India. Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 24 أغسطس 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Figures at a glance" (PDF). 2011 Provisional census data. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 أكتوبر 2011. Retrieved 17 سبتمبر 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Karnataka Budget 2018-19" (PDF). Karnataka Finance Dept. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 مارس 2018. Retrieved 15 مارس 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Karnataka Budget" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب "MOSPI Gross State Domestic Product". Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. 3 August 2018. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "MOSPI" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ 50th Report of the Commission for Linguistic Minorities in India (PDF). nclm.nic.in. p. 123. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Census 2011 (Final Data) – Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Shankar, Shiva (7 February 2018). "State flag may be a tricolour with Karnataka emblem on white". The Times of India. The Times Group. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Poem declared 'State song'". The Hindu. 11 January 2004. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Huq, Iteshamul, ed. (2015). "Introduction" (PDF). A Handbook of Karnataka (Fifth ed.). Karnataka Gazetteer Department. p. 48.

- ^ أ ب "Sub-national HDI – Area Database". Global Data Lab. Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "Seven Indian villages where people speak in Sanskrit". 24 September 2017. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Know about these 4 Indian villages where SANSKRIT is still their first language". Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Five Indian villages where sanskrit is spoken". Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ See Lord Macaulay's life of Clive and James Talboys Wheeler: Early History of British India, London (1878) p.98. The principal meaning is the western half of this area, but the rulers there controlled the Coromandel Coast as well.

- ^ Paddayya, K.; et al. (10 September 2002). "Recent findings on the Acheulian of the Hunsgi and Baichbal valleys, Karnataka, with special reference to the Isampur excavation and its dating". Current Science. 83 (5): 641–648.

- ^ S. Ranganathan. "THE Golden Heritage of Karnataka". Department of Metallurgy. Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. Archived from the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ^ "Trade". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ From the Talagunda inscription (Dr. B. L. Rice in Kamath (2001), p. 30.)

- ^ Moares (1931), p. 10.

- ^ Adiga and Sheik Ali in Adiga (2006), p. 89.

- ^ Ramesh (1984), pp. 1–2.

- ^ From the Halmidi inscription (Ramesh 1984, pp. 10–11.)

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 10.

- ^ The Chalukyas hailed from present-day Karnataka (Keay (2000), p. 168.)

- ^ The Chalukyas were native Kannadigas (N. Laxminarayana Rao and Dr. S. C. Nandinath in Kamath (2001), p. 57.)

- ^ Altekar (1934), pp. 21–24.

- ^ Masica (1991), pp. 45–46.

- ^ Balagamve in Mysore territory was an early power centre (Cousens (1926), pp. 10, 105.)

- ^ Tailapa II, the founder king was the governor of Tardavadi in modern Bijapur district, under the Rashtrakutas (Kamath (2001), p. 101.).

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 115.

- ^ Foekema (2003), p. 9.

- ^ أ ب Sastri (1955), p.164

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 132–134.

- ^ Sastri (1955), pp. 358–359, 361.

- ^ Foekema (1996), p. 14.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 122–124.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 157–160.

- ^ Kulke and Rothermund (2004), p. 188.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 190–191.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 201.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 202.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 207.

- ^ Jain, Dhanesh; Cardona, George (2003). Jain, Dhanesh; Cardona, George (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge language family series. Vol. 2. Routledge. p. 757. ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7.

- ^ Pinto, Pius Fidelis (1999). History of Christians in coastal Karnataka, 1500–1763 A.D. Mangalore: Samanvaya Prakashan. p. 124.

- ^ A History of India by Burton Stein p.190

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 171.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 171, 173, 174, 204.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 231–234.

- ^ "Rani Chennamma of Kittur". Archived from the original on 18 April 2017.

- ^ Kamath, Suryanath (20 May 2007). "The rising in the south". The Printers (Mysore) Private Limited. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Ninan, Prem Paul (1 November 2005). "History in the making". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "Karnataka Population Sex Ratio in Karnataka Literacy rate data". Archived from the original on 7 August 2013.

- ^ "Karnataka Religion Data – Census 2011". Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ^ "Envisaging a healthy growth". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Karnataka bets big on healthcare tourism". The Hindu Business Line, dated 2004-11-23. 2004, The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 September 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ "Ticking child healthcare time bomb". The Education World. Education World. Archived from the original on 17 March 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 150-152

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 152-154.

- ^ Sastri (1955), p. 396.

- ^ Sastri (1955), p. 398.

- ^ "Dasara fest panel meets Thursday". The Times of India, dated 2003-07-22. Times Internet Limited. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

المصادر

- John Keay, India: A History, 2000, Grove publications, New York, ISBN 0-8021-3797-0

- Dr. Suryanath U. Kamath, Concise history of Karnataka, 2001, MCC, Bangalore (Reprinted 2002) OCLC: 7796041

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, From Prehistoric times to fall of Vijayanagar, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002) ISBN 0-19-560686-8..

- R. Narasimhacharya, History of Kannada Literature, 1988, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras,1988, ISBN 81-206-0303-6.

- K.V. Ramesh, Chalukyas of Vatapi, 1984, Agam Kala Prakashan, Delhi ISBN 3987-10333

- Malini Adiga (2006), The Making of Southern Karnataka: Society, Polity and Culture in the early medieval period, AD 400-1030, Orient Longman, Chennai, ISBN 81 250 2912 5

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1934) [1934]. The Rashtrakutas And Their Times; being a political, administrative, religious, social, economic and literary history of the Deccan during C. 750 A.D. to C. 1000 A.D. Poona: Oriental Book Agency. OCLC 3793499.

- Masica, Colin P. (1991) [1991]. The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521299446.

- Cousens, Henry (1996) [1926]. The Chalukyan Architecture of Kanarese District. New Delhi: Archeological Survey of India. OCLC 37526233.

- Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, fourth edition, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-32919-1

- Foekema, Gerard [2003] (2003). Architecture decorated with architecture: Later medieval temples of Karnataka, 1000-1300 AD. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 81-215-1089-9.

وصلات خارجية

- Official website of the Government of Karnataka

- Karnataka Government Information Department

- كرناتكا at the Open Directory Project

|

مهارشترا | گوا |

| |

| أندرا پرادش | بحر العرب | |||

| تاميل نادو | كرالا |

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox settlement with image map1 but not image map

- Articles containing كنادا-language text

- مقالات تتضمن نطق مسجل

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- كرناتكا

- ولايات وأقاليم الهند

- دول وأراضي تأسست في 1956

- بذرة جغرافيا الهند