كرلا

كرلا

Kerala Kēraḷam | |

|---|---|

|

مع عقارب الساعة من أعلى: Niyamasabha Mandiram، حقول الأرز في Kuttanad، شاطئ Kovalam، مؤدي Kathakali، Athirappilly Falls، عوامة | |

| الكنية: بلد الرب، وحديقة توابل الهند، وأرض جوز الهند | |

موقع كرلا | |

| الإحداثيات (ثيروڤاننثاپورام): 8°30′N 77°00′E / 8.5°N 77°E | |

| البلد | |

| الولائية | 1956 نوفمبر 1 |

| العاصمة | ثيروڤاننثاپورام |

| الأضلع | 14 |

| الحكومة | |

| • الكيان | حكومة كرلا |

| • الحاكم | P. Sathasivam[1] |

| • كبير الوزراء | Pinarayi Vijayan (CPI (M)) |

| • المجلس التشريعي | أحادي الغرفة (141 مقعد)[2] |

| • الدوائر البرلمانية | راجيا سابها 9 لوك سابها 20 |

| • المحكمة العالية | محكمة كرلا العالية كوتشي |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 38٬863 كم² (15٬005 ميل²) |

| ترتيب المساحة | 22nd |

| أعلى منسوب | 2٬695 m (8٬842 ft) |

| أوطى منسوب | −2٫2 m (−7٫2 ft) |

| التعداد (2011)[2] | |

| • الإجمالي | 33٬387٬677 |

| • الترتيب | 13th |

| • الكثافة | 860/km2 (2٬200/sq mi) |

| صفة المواطن | Keralite, مليالي |

| GDP (2018–19) | |

| • إجمالي | ₹7٫73 lakh crore (97 بليون US$) |

| • للفرد | ₹162٬718 (US$2٬000) |

| اللغات | |

| • الرسمية | مليالم[5] |

| • الرسمية الإضافية | الإنگليزية[6] |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL |

| لوحة السيارة | KL |

| HDI (2018) | ▲ 0.784[7] (High) · الأولى |

| محو الأمية (2011) | 94%[8] |

| نسبة الجنس (2011) | 1084 ♀/1000 ♂[8] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | kerala |

| الرموز كرلا | |

| الشعار | |

| الطائر | أبو قرن عملاق |

| السمك | Green chromide |

| الزهرة | Kanikonna |

| الفاكهة | جاكية |

| الشجرة | شجرة جوز الهند |

| احداثيات | |

| المساحة | |

| العاصمة | ثيروڤاننثاپورام (تريڤاندرم) |

| أكبر مدينة | ثيروڤاننثاپورام |

| Region | جنوب الهند |

| المقاطعات | 14 |

| اللغة | مليالم |

| التشريع (مقاعد) | أحادي الغرفة () |

كـِرلا (إنگليزية: Kerala؛ /ˈkɛrələ/)، ويشار إليها إقليمياً بإسم Keralam هي ولاية تقع جنوب غرب الهند على ساحل ملبار. وهي ذات كثافة سكانية عالية إذ يبلغ عدد سكانها 29,011,237 نسمة حسب تعداد 1991، مساحتها 38,863 كم²، ونسبة التعليم تصل إلى نحو 90% بين السكان. والولاية فقيرة في الموارد الطبيعية، ويعتمد اقتصادها على الزراعة وصيد الأسماك والتعدين والمنتجات الصناعية. ويرأس الولاية حاكم يساعده وزير. وقد تشكلت في 1 نوفمبر 1956 حسب قانون إعادة تنظيم الولايات بضم مختلف المناطق الناطقة بلغة مليالم. وبمساحة 38,863 كم² فهي يحدها كرناتكا من الشمال والشمال الشرقي، و تاميل نادو من الشرق والجنوب، وبحر لاكشادويپ من الغرب. وبتعداد 33,387,677 نسمة حسب إحصاء 2011، فإن ترتيب كرلا هو الثاني عشر بين الولايات حسب التعداد ومقسمة إلى 14 ضلع. مليالم هي أكثر اللغات شيوعاً واللغة الرسمية للولاية. عاصمة الولاية هي ثيروڤاننثاپورام (تريڤاندروم)، المدن الرئيسية الأخرى تضم كوچي، و كوژيكوده، و ثريسور، و كولام، و كوتايام، Alappuzha, كاننور, Palakkad، و Malappuram.

كانت المنطقة مُصدِّراً بارزاً للتوابل منذ سنة 3000 ق.م. وحتى القرن الثالث. وكانت أسرة چـِرا أول مملكة قوية متمركزة في كرلا، بالرغم من أنها كثيراً ما تعرضت لهجمات من حكام تشولا و پانديا المجاورين. وأثناء فترة چـِرا، بقيت كرلا مركزاً عالمياً لتجارة التوابل. ولاحقاً في القرن الخامس عشر، جذبت تجارة التوابل السخية التجار البرتغاليين إلى كرلا، وسرعان ما مهد ذلك الطريق للاستعمار الأوروپي لكل الهند. بعد الاستقلال، انضمت تراڤنكور وكوتشي إلى جمهورية الهند وحصلت تراڤنكور-كوتشي على وضع ولاية. ولاحقاً، تشكلت الولاية في 1956 بدمج ضلع ملبار، و تراڤنكور-كوتشي (باستثناء أربع طلوقات جنوبية)، وطلوقات Kasargod و جنوب كنارا.

Kerala is the state with the lowest positive population growth rate in India (3.44%) and has a density of 860 people per km2. The state has the highest Human Development Index (HDI) (0.790) in the country according to the Human Development Report 2011.[9] It also has the highest literacy rate 95.5%, the highest life expectancy (Almost 77 years) and the highest sex ratio (as defined by number of women per 1000 men: 1,084 women per 1000 men) among all Indian states. Kerala has the lowest homicide rate among Indian states, for 2011 it was 1.1 per 100,000.[10] A survey in 2005 by Transparency International ranked it as the least corrupt state in the country. Kerala has witnessed significant emigration of its people, especially to the Gulf states during the Gulf Boom during the 1970s and early 1980s, and its economy depends significantly on remittances from a large Malayali expatriate community. Hinduism is practised by more than half of the population, followed by Islam and Christianity. The culture of the state traces its roots from 3rd century CE. It is a synthesis of Aryan and Dravidian cultures, developed over centuries under influences from other parts of India and abroad.

Production of pepper and natural rubber contributes to a significant portion of the total national output. In the agricultural sector, coconut, tea, coffee, cashew and spices are important. The state's coastline extends for 595 kilometres (370 mi), and around 1.1 million people of the state are dependent on the fishery industry which contributes 3% of the state's income. The state's 145,704 kilometres (90,536 mi) of roads, constitute 4.2% of all Indian roadways. There are three existing and two proposed international airports. Waterways are also used for transportation. The state has the highest media exposure in India with newspapers publishing in nine different languages; mainly English and Malayalam. Kerala is an important tourist destination, with backwaters, beaches, Ayurvedic tourism, and tropical greenery among its major attractions.

أصل الاسم

A 3rd-century BCE rock inscription by the Mauryan emperor Asoka the Great refers to the local ruler as Keralaputra (Sanskrit for "son of Kerala"; or "son of Chera[s]", this is contradictory to a popular theory that etymology derives "kerala" from "kera", or coconut tree in Malayalam).[11]

Two thousand years ago, one of three states in the region was called Cheralam in Classical Tamil: Chera and Kera are variants of the same word.[12] The Graeco-Roman trade map Periplus Maris Erythraei refers to this Keralaputra as Celobotra.[13] Ralston Marr derives "Kerala" from the word "Cheral" that refers to the oldest known dynasty of Kerala kings.[14] In turn the word "Cheral" is derived from the proto-Tamil-Malayalam word for "lake".

النصوص الدينية القديمة

According to Hindu mythology, the lands of Kerala were recovered from the sea by the axe-wielding warrior sage Parasurama, 6th avatar of Vishnu, hence Kerala is also called Parasurama Kshetram ("The Land of Parasurama"). Parasurama threw his axe across the sea, and the water receded as far as it reached. According to legend, this new area of land extended from Gokarna to Kanyakumari.[15] Consensus among scientific geographers agrees that a substantial portion of this area was under the sea in ancient times.[16] The land which rose from sea was filled with salt and unsuitable for habitation so Parasurama invoked the Snake King Vasuki, who spat holy poison and converted the soil into fertile lush green land. Out of respect, Vasuki and all snakes were appointed as protectors and guardians of the land. The legend later expanded, and found literary expression in the 17th or 18th century with Keralolpathi, which traces the origin of aspects of early Kerala society, such as land tenure and administration, to the story of Parasurama.[17] In medieval times Kuttuvan may have emulated the Parasurama tradition by throwing his spear into the sea to symbolize his lordship over it.[18] Another much earlier Puranic character associated with Kerala is Mahabali, an Asura and a prototypical king of justice, who ruled the earth from Kerala. He won the war against the Devas, driving them into exile. The Devas pleaded before Lord Vishnu, who took his fifth incarnation as Vamana and pushed Mahabali down to Patala (the netherworld) to placate the Devas. There is a belief that, once a year during the Onam festival, Mahabali returns to Kerala.[19]

التاريخ

قبل التاريخ

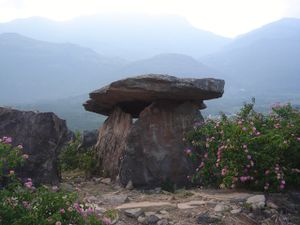

Prehistorical archaeological findings include dolmens of the Neolithic era in the Marayur area in Idukki district. They are locally known as "muniyara", derived from muni (hermit or sage) and ara (dolmen).[20] Rock engravings in the Edakkal Caves (in Wayanad) are thought to date from the early to late Neolithic eras around 6000 BCE.[21][22] Archaeological studies have identified many Mesolithic, Neolithic and Megalithic sites in Kerala.[23] The studies point to the indigenous development of the ancient Kerala society and its culture beginning from the Paleolithic age, and its continuity through Mesolithic, Neolithic and Megalithic ages.[24] However, foreign cultural contacts have assisted this cultural formation.[25] The studies suggest possible relationship with Indus Valley Civilization during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age.[26]

الفترة القديمة

Kerala was a major spice exporter from as early as 3000 BCE, according to Sumerian records.[27] Its fame as the land of spices attracted ancient Babylonians, Assyrians and Egyptians to the Malabar Coast in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE. Arabs and Phoenicians were also successful in establishing their prominence in the Kerala trade during this early period.[28] The word Kerala is first recorded (as Keralaputra) in a 3rd-century BCE rock inscription (Rock Edict 2) left by the Maurya emperor Asoka (274–237 BCE).[29] The Land of Keralaputra was one of the four independent kingdoms in southern India during Asoka's time, the others being Chola, Pandya, and Satiyaputra.[30] Scholars hold that Keralaputra is an alternate name of the Cheras, the first powerful dynasty based on Kerala.[31][32] These territories once shared a common language and culture, within an area known as Tamiḻakam.[33] While the Cheras ruled the major part of modern Kerala, its southern tip was in the kingdom of Pandyas,[34] which had a trading port sometimes identified in ancient Western sources as Nelcynda (or Neacyndi).[35] At later times the region fell under the control of the Pandyas, Cheras, and Cholas. Ays and Mushikas were two other remarkable dynasties of ancient Kerala, whose kingdoms lay to the south and north of Cheras respectively.[36][37]

العصور الوسطى المبكرة

العصر الاستعماري

The monopoly of maritime spice trade in the Indian Ocean stayed with Arabs during the high and late medieval periods. However, the dominance of Middle East traders got challenged in the European Age of Discovery during which the spice trade, particularly in black pepper, became an influential activity for European traders.[38] Around the 15th century, the Portuguese began to dominate the eastern shipping trade in general, and the spice-trade in particular, culminating in Vasco Da Gama's arrival in Kappad Kozhikode in 1498.[39][40][41] The Zamorin of Calicut permitted the new visitors to trade with his subjects. The Portuguese trade in Calicut prospered with the establishment of a factory and fort in his territory. However, Portuguese attacks on Arab properties in his jurisdiction provoked Zamorin and finally led to conflicts between them. The Portuguese took advantage of the rivalry between Zamorin and king of Kochi; they allied with Kochi and when Francisco de Almeida was appointed as the Viceroy of Portuguese India in 1505, his headquarters was at Kochi. During his reign, the Portuguese managed to dominate relations with Kochi and established a few fortresses in Malabar coast.[42] Nonetheless, the Portuguese suffered severe setbacks from the attacks of Zamorin forces; especially from naval attacks under the leadership of admirals of Calicut known as Kunjali Marakkars, which compelled them to seek a treaty. In 1571, Portuguese were defeated by the Zamorin forces in the battle at Chaliyam fort.[43]

The weakened Portuguese were ousted by the Dutch East India Company, who took advantage of continuing conflicts between Kozhikode and Kochi to gain control of the trade.[44] The Dutch in turn were weakened by constant battles with Marthanda Varma of the Travancore Royal Family, and were defeated at the Battle of Colachel in 1741.[45] An agreement, known as "Treaty of Mavelikkara", was signed by the Dutch and Travancore in 1753, according to which the Dutch were compelled to detach from all political involvements in the region.[46][47][48] In the meantime, Marthanda Varma annexed many northern kingdoms through military conquests, resulting in the rise of Travancore to a position of preeminence in Kerala.[49]

In 1766, Hyder Ali, the ruler of Mysore invaded northern Kerala.[50] His son and successor, Tipu Sultan, launched campaigns against the expanding British East India Company, resulting in two of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars.[51][52] Tipu ultimately ceded Malabar District and South Kanara to the Company in the 1790s; both were annexed to the Madras Presidency of British India in 1792.[53][54][55] The Company forged tributary alliances with Kochi in 1791 and Travancore in 1795.[56] Thus, by the end of 18th century, the whole of Kerala fell under the control of the British, either administered directly or under suzerainty.[57]

There were major revolts in Kerala during its transition to democracy in the 20th century; most notable among them is the 1921 Malabar Rebellion and the many social struggles in Travancore. In the Malabar Rebellion, Mappila Muslims of Malabar rioted against Hindu zamindars and the British Raj.[58] Some social struggles against caste inequalities also erupted in the early decades of 20th century, leading to the 1936 Temple Entry Proclamation that opened Hindu temples in Travancore to all castes;[59]

جغرافيا

| أخفClimate data for Kerala | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.4) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

34 (93) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

34 (93) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

| Source: [60] | |||||||||||||

الفلورا والفونا

الأقسام الإدارية

| المدن الرئيسية في كرلا (تقدير تعداد الهند 2001)[61] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الترتيب | المدينة\البلدة | المقاطعة | التعداد | ||||||||

| 01 | ثيروڤاننثاپورام | ثيروڤاننثاپورام | 744,983 | ||||||||

| 02 | كوچي | Ernakulam | 595,575 | ||||||||

| 03 | كوژيكوده | كوژيكوده | 436,556 | ||||||||

| 04 | كولام | كولام | 361,029 | ||||||||

| 05 | ثريسور | ثريسور | 317,526 | ||||||||

| 06 | ألاپوژا | ألاپوژا | 187,495 | ||||||||

| 07 | پلاكـّاد | پلاكـّاد | 130,767 | ||||||||

| 08 | ثلاسري | كانـّور | 99,387 | ||||||||

| 09 | پوناني | ملاپورام | 87,495 | ||||||||

| 10 | مانرجي | ملاپورام | 83,024 | ||||||||

الحكومة

معرض الصور

Thiruvathira kali: a dance performed by women in Kerala during Onam festival

Paddy fields of Kerala

A house boat on the backwaters near Alleppey in Kerala

Resorts dot the length and breadth of Kerala.

Sunset at Varkala Beach

Kalaripayattu a martial art of Kerala

E. M. S. Namboodiripad is often regarded as the most influential personality in post-colonial Kerala

الاقتصاد

السكان

| أظهرمناحي التعداد[62][63] |

|---|

الثقافة

ملاحظات

- ^ α: Around the 9th century, the Cheras fell from power. Several small kingdoms (swaroopams) formed under the leadership of Nair chieftains, filling the resulting political vacuum.[41]

الهامش

- ^ Menon, Gireesh (5 September 2014). "Sathasivam sworn in as Kerala Governor". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ "Kerala Population Census data 2011". Census 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Kerala Budget Analysis 2018–19" (PDF). PRS Legislative Research. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "STATE WISE DATA" (PDF). esopb.gov.in. Economic and Statistical Organization, Government of Punjab. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ "52nd report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2014 to June 2015)" (PDF). Ministry of Minority Affairs (Government of India). 29 March 2016. p. 132. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jacob, Aneesh (27 November 2015). "Malayalam to be only official language in state". Mathrubhumi.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsnhdi-gdl - ^ أ ب "Census 2011 (Final Data) - Demographic details, Literate Population (Total, Rural & Urban)" (PDF). planningcommission.gov.in. Planning Commission, Government of India. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةIDHR 2011 - ^ http://ncrb.nic.in/CD-CII2011/cii-2011/Table%203.1.pdf

- ^ A. Sreedhara Menon (1987). Political History of Modern Kerala. D C Books. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-81-264-2156-5. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Nicasio Silverio Sainz (1972). Cuba y la Casa de Austria. Ediciones Universal. p. 120. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Robert Caldwell (1 December 1998). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages. Asian Educational Services. p. 92. ISBN 978-81-206-0117-8. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ John Ralston Marr (1985). The Eight Anthologies. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 263.

- ^ Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–212. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey Of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ M. T. Narayanan (1 January 2003). Agrarian Relations in Late Medieval Malabar. Northern Book Centre. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-81-7211-135-9. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ P. 204 Ancient Indian History By Madhavan Arjunan Pillai

- ^ Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Unlocking the secrets of history". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 December 2004.

- ^ Subodh Kapoor (1 July 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 2184. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Tourism information on districts –Wayanad, official website of the Govt. of Kerala

- ^ Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 116. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. pp. 118, 123. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ Udai Prakash Arora; A. K. Singh (1 January 1999). Currents in Indian History, Art, and Archaeology. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 123. ISBN 978-81-86565-44-5. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Symbols akin to Indus valley culture discovered in Kerala". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 29 September 2009.

- ^ Striving for sustainability, environmental stress and democratic initiatives in Kerala, p. 79; ISBN 81-8069-294-9, Srikumar Chattopadhyay, Richard W. Franke; Year: 2006.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (1 January 2007). A Survey Of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "Kerala." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2011. Web. 26 December 2011.

- ^ Vincent A. Smith; A. V. Williams Jackson (30 November 2008). History of India, in Nine Volumes: Vol. II – From the Sixth Century BCE to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great. Cosimo, Inc. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-1-60520-492-5. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 193. GGKEY:2W0QHXZ7K40. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Bhanwar Lal Dwivedi (1 January 1994). Evolution of Education Thought in India. Northern Book Centre. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-81-7211-059-8. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Kanakasabhai, V. (1997). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0150-5. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ^ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 385. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ James Oliver Thomson (1948). History of ancient geography – Google Books. Biblo & Tannen Publishers, 1948. ISBN 978-0-8196-0143-8. Retrieved 30 July 2009.. See also [1]

- ^ S. S. Shashi (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. Anmol Publications. p. 1207. ISBN 978-81-7041-859-7. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Murkot Ramunny (1 January 1993). Ezhimala: The Abode of the Naval Academy. Northern Book Centre. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-7211-052-9. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ Corn, Charles; Glasserman, Debbie (March 1999). The Scents of Eden: A History of the Spice Trade. Kodansha America. ISBN 1-56836-249-8.

- ^ Ravindran PN (2000). Black Pepper: Piper Nigrum. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-5702-453-5. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ Curtin PD (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 0-521-26931-8.

- ^ أ ب Mundadan AM (1984). Volume I: From the Beginning up to the Sixteenth Century (up to 1542). History of Christianity in India. Church History Association of India. Bangalore: Theological Publications.

- ^ J. L. Mehta (1 January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: Volume One: 1707–1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 324–327. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ K. K. N. Kurup (1 January 1997). India's Naval Traditions: The Role of Kunhali Marakkars. Northern Book Centre. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-81-7211-083-3. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ South Asia 2006. Taylor & Francis. 1 December 2005. p. 289. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Murkot Ramunny (1 January 1993). Ezhimala: The Abode of the Naval Academy. Northern Book Centre. pp. 57–. ISBN 978-81-7211-052-9. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Anjana Singh (30 April 2010). Fort Cochin in Kerala, 1750–1830: The Social Condition of a Dutch Community in an Indian Milieu. BRILL. pp. 22–52. ISBN 978-90-04-16816-9. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ S. Krishna Iyer (1995). Travancore Dutch relations, 1729–1741. CBH Publications. p. 49. ISBN 978-81-85381-42-8. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Mark de Lannoy (1997). The Kulasekhara Perumals of Travancore: history and state formation in Travancore from 1671 to 1758. Leiden University. p. 190. ISBN 978-90-73782-92-1. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ A. Sreedhara Menon (1987). Political History of Modern Kerala. D C Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-264-2156-5. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ Raghunath Rai. History. FK Publications. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-81-87139-69-0. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ British Museum; Anna Libera Dallapiccola (22 June 2010). South Indian Paintings: A Catalogue of the British Museum Collection. Mapin Publishing Pvt Ltd. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-0-7141-2424-7. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Edgar Thorpe, Showick Thorpe; Thorpe Edgar. The Pearson CSAT Manual 2011. Pearson Education India. p. 99. ISBN 978-81-317-5830-4. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ The Edinburgh Gazetteer. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. 1827. pp. 63–. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Dharma Kumar (1965). Land and Caste in South India: Agricultural Labor in the Madras Presidency During the Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive. pp. 87–. GGKEY:T72DPF9AZDK. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ K.P. Ittaman (1 June 2003). History of Mughal Architecture Volume Ii. Abhinav Publications. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-81-7017-034-1. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Superintendent of Government Printing (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India (Provincial Series): Madras. Calcutta: Government of India. p. 22. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ Kakkadan Nandanath Raj; Michael Tharakan; Rural Employment Policy Research Programme (1981). Agrarian reform in Kerala and its impact on the rural economy: a preliminary assessment. International Labour Office. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

{{cite book}}:|author3=has generic name (help) - ^ Qureshi, MN (1999). Pan-Islam in British Indian Politics: A Study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918–1924. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. pp. 445–447. ISBN 90-04-10538-7. OCLC 231706684.

- ^ Bardwell L. Smith (1976). Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. BRILL. pp. 35–42. ISBN 978-90-04-04510-1. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةautogenerated14 - ^ "Kerala". Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. 2007-03-18. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ^ أ ب "Population of India (1951-2001)" (PDF). Census of India. Indian Ministry of Finance. 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ "Census of India". Retrieved 2009-04-12.

المراجع

- Bhagyalekshmy, S (2004), "Contribution of Travancore to Karnatic Music", Information & Public Relations Department—Thiruvananthapuram (Government of Kerala), <http://www.kerala.gov.in/music/music1.pdf>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Bhagyalekshmy, S (2004d), "Contribution of Travancore to Karnatic Music", Information & Public Relations Department—Thiruvananthapuram (Government of Kerala): 29–37, <http://www.kerala.gov.in/music/music4.pdf>. Retrieved on 20 January 2006.

- Foundation For Humanization (2002), "Human Index", Humanscape IX (V), <http://www.humanscape.org/Humanscape/new/may02/humanindex.htm>. Retrieved on 22 February 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2001), "Ranking of districts by Sex Ratio and Population density", Statistics for Planning 2001 (Government of Kerala), <http://www.kerala.gov.in/statistical/vitalstatistics/1.03.pdf>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2002b), "Marumakkathayam", Department of Public Relations (Government of Kerala), <http://www.prd.kerala.gov.in/prd2/keralam/kathayam.htm>. Retrieved on 29 January 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2004), "Economic Review 2004: An Overview", Department of Planning and Economic Affairs (Government of Kerala), <http://www.kerala.gov.in/dept_planning/er/chapter1.pdf>. Retrieved on 15 March 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2004c), "Economic Review 2004: Income and Population", Department of Planning and Economic Affairs (Government of Kerala), <http://www.kerala.gov.in/dept_planning/er/chapter3.pdf>. Retrieved on 15 March 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2004f), "Economic Review 2004: Environment", Department of Planning and Economic Affairs (Government of Kerala), <http://www.kerala.gov.in/dept_planning/er/chapter6.pdf>. Retrieved on 15 March 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2004r), "Economic Review 2004: Gender and Development", Department of Planning and Economic Affairs (Government of Kerala), <http://www.kerala.gov.in/dept_planning/er/chapter18.pdf>. Retrieved on 25 March 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2005), "History & Culture: Early History", Government of Kerala, <http://www.kerala.gov.in/>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2005b), "General Features", Government of Kerala, <http://www.kerala.gov.in/knowkerala/generalfeatures.htm>. Retrieved on 18 January 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2005c), "Kerala at a Glance", Government of Kerala, <http://www.kerala.gov.in/>. Retrieved on 22 January 2006.

- Government of Kerala (2006), "Towards an entitlement-based approach to poverty reduction: Development and application of entitlement index.", Government of Kerala, <http://www.kerala.gov.in/archive/111.pdf>. Retrieved on 22 February 2006.

- Kanakasabhai, V. (1997). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120601505. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- Office of the Registrar General (2001), "Chapter 5: Density of Population", Census of India (2001), <http://www.censusindia.gov.in/>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Office of the Registrar General (2001b), "Census of India 2001: Provisional Population Totals", Census of India (2001), <http://www.censusindia.gov.in/>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Office of the Registrar General (2001c), "Number of Literates & Literacy Rates", Census of India (2001), <http://www.censusindia.gov.in/>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Office of the Registrar General (2004), "Data on Religion", Census of India 2001, <http://www.censusindia.gov.in/>. Retrieved on 18 January 2006.

- Omcherry, L (1999), "Music of Kerala", Essays on the Cultural Formation of Kerala, <http://www.keralahistory.ac.in/publication_n.htm>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Plunkett, R; T, Davis, P, Greenway, P Cannon & P Harding (2001), Lonely Planet South India, Lonely Planet, ISBN.

- Rajeevan, B (1999), "Cultural Formation of Kerala", Essays on the Cultural Formation of Kerala, <http://www.keralahistory.ac.in/publication_n.htm>. Retrieved on 12 January 2006.

- Ramakrishnan, V (2001), "Communal tension high in Kerala", BBC News, <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/1702270.stm>. Retrieved on 28 January 2006.

- Sadasivan, S. N. (2000). A social history of India (illustrated ed.). APH Publishing. ISBN 9788176481700. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- Sunny, C (2004), "Domestic Violence Against Women in Ernakulam District", Centre for Development Studies, <http://krpcds.org/publication/downloads/55.pdf>. Retrieved on 3 March 2006.

وصلات خارجية

- الحكومة

- Official entry portal of the Government of Kerala

- Department of Tourism, Government of Kerala

- Directorate of Census Operations of Kerala

- غيرها

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لصفات المواطن

- Pages using Infobox region symbols with overlapping parameters

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- كرلا

- ولايات وأقاليم الهند

- دول وأراضي تأسست في 1956