زحل

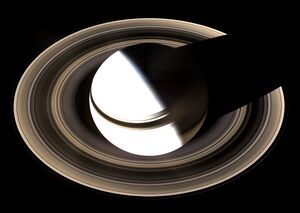

زحل، كما شاهده كاسيني-هويگنز | |||||||||||||

| السمات المدارية[7] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| حقبة J2000.0 | |||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 1,514.50 million km (10.1238 AU) | ||||||||||||

| Perihelion | 1,352.55 million km (9.0412 AU) | ||||||||||||

| 1,433.53 million km (9.5826 AU) | |||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0565 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 378.09 days | |||||||||||||

Average orbital speed | 9.68 km/s (6.01 mi/s) | ||||||||||||

| 317.020°[2] | |||||||||||||

| Inclination | |||||||||||||

| 113.665° | |||||||||||||

| 2032-Nov-29[4] | |||||||||||||

| 339.392°[2] | |||||||||||||

| Known satellites | 146 with formal designations; innumerable additional moonlets.[5][6] | ||||||||||||

| السمات الطبيعية[7] | |||||||||||||

نصف القطر المتوسط | 58,232 km (36,184 mi)[أ]

9.1402 Earths | ||||||||||||

Mean radius | 58,232 km (36,184 mi)[أ]

9.1402 Earths | ||||||||||||

Equatorial radius |

| ||||||||||||

Polar radius |

| ||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0.09796 | ||||||||||||

| Circumference |

| ||||||||||||

| Volume |

| ||||||||||||

| Mass |

| ||||||||||||

Mean density | 0.687 g/cm3 (0.0248 lb/cu in)[ب] (less than water) 0.1246 Earths | ||||||||||||

| 0.22[10] | |||||||||||||

| 35.5 km/s (22.1 mi/s)[أ] | |||||||||||||

| 10 h 32 m 36 s; 10.5433 hours,[11] 10 h 39 m; 10.7 hours[1] | |||||||||||||

Sidereal rotation period | 10h 33m 38s قالب:+- [12][13] | ||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity | 9.87 km/s (6.13 mi/s; 35,500 km/h)[أ] | ||||||||||||

| 26.73° (to orbit) | |||||||||||||

North pole right ascension | 40.589°; 2h 42m 21s | ||||||||||||

North pole declination | 83.537° | ||||||||||||

| Albedo | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| −0.55[16] to +1.17[16] | |||||||||||||

| −9.7[17] | |||||||||||||

| 14.5″ to 20.1″ (excludes rings) | |||||||||||||

| Atmosphere[7] | |||||||||||||

Surface pressure | 140 kPa[20] | ||||||||||||

| 59.5 km (37.0 mi) | |||||||||||||

| Composition by volume | |||||||||||||

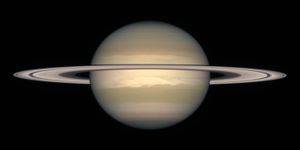

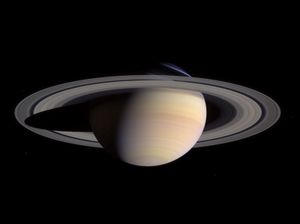

زحل Saturn هو سادس كوكب من الشمس وثاني أكبر الكواكب حجماً في المجموعة الشمسية، وثاني أكبر كتلة أيضاً، بعد المشتري، إذ إن قطره هو 9.5 ضعف قطر الأرض. إنه كوكب غازي عملاق، يتم دورة كاملة حول نفسه في 10ـ11 ساعة (بحسب درجة العرض عليه)، ويتم دورة كاملة حول الشمس في 29.5 سنة. بُعده الوسطي عن الشمس 9.54 وحدة فلكية (1.429.400.000 كيلو متر).[21][22] It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 times more massive.[23][24][25]

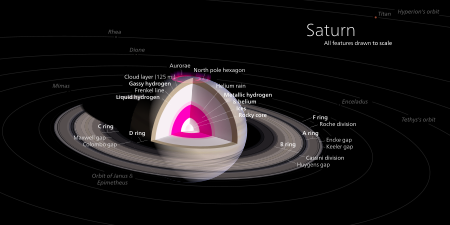

Saturn's interior is thought to be composed of a rocky core, surrounded by a deep layer of metallic hydrogen, an intermediate layer of liquid hydrogen and liquid helium, and finally, a gaseous outer layer. Saturn has a pale yellow hue due to ammonia crystals in its upper atmosphere. An electrical current within the metallic hydrogen layer is thought to give rise to Saturn's planetary magnetic field, which is weaker than Earth's, but which has a magnetic moment 580 times that of Earth due to Saturn's larger size. Saturn's magnetic field strength is around one-twentieth of Jupiter's.[26] The outer atmosphere is generally bland and lacking in contrast, although long-lived features can appear. Wind speeds on Saturn can reach 1,800 kilometres per hour (1,100 miles per hour).

The planet has a prominent ring system, which is composed mainly of ice particles, with a smaller amount of rocky debris and dust. At least 146 moons[27] are known to orbit the planet, of which 63 are officially named; this does not include the hundreds of moonlets in its rings. Titan, Saturn's largest moon and the second largest in the Solar System, is larger (while less massive) than the planet Mercury and is the only moon in the Solar System to have a substantial atmosphere.[28]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاسم والرمز

Saturn is named after the Roman god of wealth and agriculture and father of Jupiter. Its astronomical symbol (![]() ) has been traced back to the Greek Oxyrhynchus Papyri, where it can be seen to be a Greek kappa-rho ligature with a horizontal stroke, as an abbreviation for Κρονος (Cronus), the Greek name for the planet (

) has been traced back to the Greek Oxyrhynchus Papyri, where it can be seen to be a Greek kappa-rho ligature with a horizontal stroke, as an abbreviation for Κρονος (Cronus), the Greek name for the planet (![]() ).[29]

It later came to look like a lower-case Greek eta, with the cross added at the top in the 16th century to Christianize this pagan symbol.

).[29]

It later came to look like a lower-case Greek eta, with the cross added at the top in the 16th century to Christianize this pagan symbol.

The Romans named the seventh day of the week Saturday, Sāturni diēs ("Saturn's Day"), for the planet Saturn.[30]

السمات الطبيعية

Saturn is a gas giant composed predominantly of hydrogen and helium. It lacks a definite surface, though it is likely to have a solid core.[31] Saturn's rotation causes it to have the shape of an oblate spheroid; that is, it is flattened at the poles and bulges at its equator. Its equatorial radius is more than 10% larger than its polar radius: 60,268 km versus 54,364 km.[7] Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune, the other giant planets in the Solar System, are also oblate but to a lesser extent. The combination of the bulge and rotation rate means that the effective surface gravity along the equator, 8.96 m/s2, is 74% of what it is at the poles and is lower than the surface gravity of Earth. However, the equatorial escape velocity of nearly 36 km/s is much higher than that of Earth.[32]

Saturn is the only planet of the Solar System that is less dense than water—about 30% less.[33] Although Saturn's core is considerably denser than water, the average specific density of the planet is 0.69 g/cm3 due to the atmosphere. Jupiter has 318 times Earth's mass,[34] and Saturn is 95 times Earth's mass.[7] Together, Jupiter and Saturn hold 92% of the total planetary mass in the Solar System.[35]

البنية الداخلية

Despite consisting mostly of hydrogen and helium, most of Saturn's mass is not in the gas phase, because hydrogen becomes a non-ideal liquid when the density is above 0.01 g/cm3, which is reached at a radius containing 99.9% of Saturn's mass. The temperature, pressure, and density inside Saturn all rise steadily toward the core, which causes hydrogen to be a metal in the deeper layers.[35]

Standard planetary models suggest that the interior of Saturn is similar to that of Jupiter, having a small rocky core surrounded by hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of various volatiles.[36] Analysis of the distortion shows that Saturn is substantially more centrally condensed than Jupiter and therefore contains a significantly larger amount of material denser than hydrogen near its centre. Saturn's central regions contain about 50% hydrogen by mass, while Jupiter's contain approximately 67% hydrogen.[37]

This core is similar in composition to Earth, but is more dense. The examination of Saturn's gravitational moment, in combination with physical models of the interior, has allowed constraints to be placed on the mass of Saturn's core. In 2004, scientists estimated that the core must be 9–22 times the mass of Earth,[38][39] which corresponds to a diameter of about 25,000 km.[40] However, measurements of Saturn's rings suggest a much more diffuse core with a mass equal to about 17 Earths and a radius equal to around 60% of Saturn's entire radius.[41] This is surrounded by a thicker liquid metallic hydrogen layer, followed by a liquid layer of helium-saturated molecular hydrogen that gradually transitions to a gas with increasing altitude. The outermost layer spans 1,000 km and consists of gas.[42][43][44]

Saturn has a hot interior, reaching 11,700 °C at its core, and radiates 2.5 times more energy into space than it receives from the Sun. Jupiter's thermal energy is generated by the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism of slow gravitational compression, but such a process alone may not be sufficient to explain heat production for Saturn, because it is less massive. An alternative or additional mechanism may be the generation of heat through the "raining out" of droplets of helium deep in Saturn's interior. As the droplets descend through the lower-density hydrogen, the process releases heat by friction and leaves Saturn's outer layers depleted of helium.[45][46] These descending droplets may have accumulated into a helium shell surrounding the core.[36] Rainfalls of diamonds have been suggested to occur within Saturn, as well as in Jupiter[47] and ice giants Uranus and Neptune.[48]

الغلاف الجوي

The outer atmosphere of Saturn contains 96.3% molecular hydrogen and 3.25% helium by volume.[49] The proportion of helium is significantly deficient compared to the abundance of this element in the Sun.[36] The quantity of elements heavier than helium (metallicity) is not known precisely, but the proportions are assumed to match the primordial abundances from the formation of the Solar System. The total mass of these heavier elements is estimated to be 19–31 times the mass of Earth, with a significant fraction located in Saturn's core region.[50]

Trace amounts of ammonia, acetylene, ethane, propane, phosphine, and methane have been detected in Saturn's atmosphere.[51][52][53] The upper clouds are composed of ammonia crystals, while the lower level clouds appear to consist of either ammonium hydrosulfide (NH

4SH) or water.[54] Ultraviolet radiation from the Sun causes methane photolysis in the upper atmosphere, leading to a series of hydrocarbon chemical reactions with the resulting products being carried downward by eddies and diffusion. This photochemical cycle is modulated by Saturn's annual seasonal cycle.[53] Cassini observed a series of cloud features found in northern latitudes, nicknamed the "String of Pearls". These features are cloud clearings that reside in deeper cloud layers.[55]

طبقات السحاب

Saturn's atmosphere exhibits a banded pattern similar to Jupiter's, but Saturn's bands are much fainter and are much wider near the equator. The nomenclature used to describe these bands is the same as on Jupiter. Saturn's finer cloud patterns were not observed until the flybys of the Voyager spacecraft during the 1980s. Since then, Earth-based telescopy has improved to the point where regular observations can be made.[56]

The composition of the clouds varies with depth and increasing pressure. In the upper cloud layers, with temperatures in the range of 100–160 K and pressures extending between 0.5–2 bar, the clouds consist of ammonia ice. Water ice clouds begin at a level where the pressure is about 2.5 bar and extend down to 9.5 bar, where temperatures range from 185 to 270 K. Intermixed in this layer is a band of ammonium hydrosulfide ice, lying in the pressure range 3–6 bar with temperatures of 190–235 K. Finally, the lower layers, where pressures are between 10 and 20 bar and temperatures are 270–330 K, contains a region of water droplets with ammonia in aqueous solution.[57]

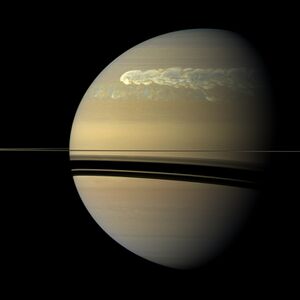

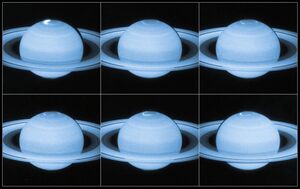

Saturn's usually bland atmosphere occasionally exhibits long-lived ovals and other features common on Jupiter. In 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope imaged an enormous white cloud near Saturn's equator that was not present during the Voyager encounters, and in 1994 another smaller storm was observed. The 1990 storm was an example of a Great White Spot, a short-lived phenomenon that occurs once every Saturnian year, roughly every 30 Earth years, around the time of the northern hemisphere's summer solstice.[58] Previous Great White Spots were observed in 1876, 1903, 1933 and 1960, with the 1933 storm being the best observed.[59] The latest giant storm was observed in 2010. In 2015, researchers used Very Large Array telescope to study Saturnian atmosphere, and reported that they found "long-lasting signatures of all mid-latitude giant storms, a mixture of equatorial storms up to hundreds of years old, and potentially an unreported older storm at 70°N".[60]

The winds on Saturn are the second fastest among the Solar System's planets, after Neptune's. Voyager data indicate peak easterly winds of 500 m/s (1,800 km/h).[61] In images from the Cassini spacecraft during 2007, Saturn's northern hemisphere displayed a bright blue hue, similar to Uranus. The color was most likely caused by Rayleigh scattering.[62] Thermography has shown that Saturn's south pole has a warm polar vortex, the only known example of such a phenomenon in the Solar System.[63] Whereas temperatures on Saturn are normally −185 °C, temperatures on the vortex often reach as high as −122 °C, suspected to be the warmest spot on Saturn.[63]

أنماط السحاب السداسية

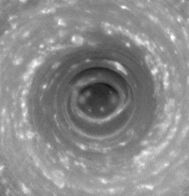

A persisting hexagonal wave pattern around the north polar vortex in the atmosphere at about 78°N was first noted in the Voyager images.[64][65][66] The sides of the hexagon are each about 14,500 km (9,000 mi) long, which is longer than the diameter of the Earth.[67] The entire structure rotates with a period of 10h 39m 24s (the same period as that of the planet's radio emissions) which is assumed to be equal to the period of rotation of Saturn's interior.[68] The hexagonal feature does not shift in longitude like the other clouds in the visible atmosphere.[69] The pattern's origin is a matter of much speculation. Most scientists think it is a standing wave pattern in the atmosphere. Polygonal shapes have been replicated in the laboratory through differential rotation of fluids.[70][71]

HST imaging of the south polar region indicates the presence of a jet stream, but no strong polar vortex nor any hexagonal standing wave.[72] NASA reported in November 2006 that Cassini had observed a "hurricane-like" storm locked to the south pole that had a clearly defined eyewall.[73][74] Eyewall clouds had not previously been seen on any planet other than Earth. For example, images from the Galileo spacecraft did not show an eyewall in the Great Red Spot of Jupiter.[75]

The south pole storm may have been present for billions of years.[76] This vortex is comparable to the size of Earth, and it has winds of 550 km/h.[76]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الغلاف المغناطيسي

Saturn has an intrinsic magnetic field that has a simple, symmetric shape—a magnetic dipole. Its strength at the equator—0.2 gauss (µT)—is approximately one twentieth of that of the field around Jupiter and slightly weaker than Earth's magnetic field.[26] As a result, Saturn's magnetosphere is much smaller than Jupiter's.[77] When Voyager 2 entered the magnetosphere, the solar wind pressure was high and the magnetosphere extended only 19 Saturn radii, or 1.1 million km (712,000 mi),[78] although it enlarged within several hours, and remained so for about three days.[79] Most probably, the magnetic field is generated similarly to that of Jupiter—by currents in the liquid metallic-hydrogen layer called a metallic-hydrogen dynamo.[77] This magnetosphere is efficient at deflecting the solar wind particles from the Sun. The moon Titan orbits within the outer part of Saturn's magnetosphere and contributes plasma from the ionized particles in Titan's outer atmosphere.[26] Saturn's magnetosphere, like Earth's, produces aurorae.[80]

المدار والدوران

The average distance between Saturn and the Sun is over 1.4 billion kilometers (9 AU). With an average orbital speed of 9.68 km/s,[7] it takes Saturn 10,759 Earth days (or about 291⁄2 years)[81] to finish one revolution around the Sun.[7] As a consequence, it forms a near 5:2 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter.[82] The elliptical orbit of Saturn is inclined 2.48° relative to the orbital plane of the Earth.[7] The perihelion and aphelion distances are, respectively, 9.195 and 9.957 AU, on average.[7][83] The visible features on Saturn rotate at different rates depending on latitude, and multiple rotation periods have been assigned to various regions (as in Jupiter's case).

Astronomers use three different systems for specifying the rotation rate of Saturn. System I has a period of 10h 14m 00s (844.3°/d) and encompasses the Equatorial Zone, the South Equatorial Belt, and the North Equatorial Belt. The polar regions are considered to have rotation rates similar to System I. All other Saturnian latitudes, excluding the north and south polar regions, are indicated as System II and have been assigned a rotation period of 10h 38m 25.4s (810.76°/d). System III refers to Saturn's internal rotation rate. Based on radio emissions from the planet detected by Voyager 1 and Voyager 2,[84] System III has a rotation period of 10h 39m 22.4s (810.8°/d). System III has largely superseded System II.[85]

A precise value for the rotation period of the interior remains elusive. While approaching Saturn in 2004, Cassini found that the radio rotation period of Saturn had increased appreciably, to approximately 10h 45m 45s قالب:+-.[86][87] An estimate of Saturn's rotation (as an indicated rotation rate for Saturn as a whole) based on a compilation of various measurements from the Cassini, Voyager and Pioneer probes is 10h 32m 35s.[88] Studies of the planet's C Ring yield a rotation period of 10h 33m 38s قالب:+- .[12][13]

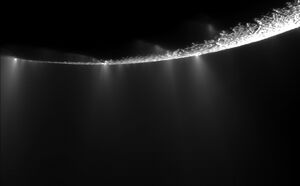

In March 2007, it was found that the variation in radio emissions from the planet did not match Saturn's rotation rate. This variance may be caused by geyser activity on Saturn's moon Enceladus. The water vapor emitted into Saturn's orbit by this activity becomes charged and creates a drag upon Saturn's magnetic field, slowing its rotation slightly relative to the rotation of the planet.[89][90][91]

An apparent oddity for Saturn is that it does not have any known trojan asteroids. These are minor planets that orbit the Sun at the stable Lagrangian points, designated L4 and L5, located at 60° angles to the planet along its orbit. Trojan asteroids have been discovered for Mars, Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune. Orbital resonance mechanisms, including secular resonance, are believed to be the cause of the missing Saturnian trojans.[92]

السواتل الطبيعية

Saturn has 146 known moons, 63 of which have formal names.[6][5] It is estimated that there are other 100±30 outer irregular moons larger than 3 km (2 mi) in diameter.[93] In addition, there is evidence of dozens to hundreds of moonlets with diameters of 40–500 meters in Saturn's rings,[94] which are not considered to be true moons. Titan, the largest moon, comprises more than 90% of the mass in orbit around Saturn, including the rings.[95] Saturn's second-largest moon, Rhea, may have a tenuous ring system of its own,[96] along with a tenuous atmosphere.[97][98][99]

Many of the other moons are small: 131 are less than 50 km in diameter.[100] Traditionally, most of Saturn's moons have been named after Titans of Greek mythology. Titan is the only satellite in the Solar System with a major atmosphere,[101][102] in which a complex organic chemistry occurs. It is the only satellite with hydrocarbon lakes.[103][104]

On 6 June 2013, scientists at the IAA-CSIC reported the detection of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the upper atmosphere of Titan, a possible precursor for life.[105] On 23 June 2014, NASA claimed to have strong evidence that nitrogen in the atmosphere of Titan came from materials in the Oort cloud, associated with comets, and not from the materials that formed Saturn in earlier times.[106]

Saturn's moon Enceladus, which seems similar in chemical makeup to comets,[107] has often been regarded as a potential habitat for microbial life.[108][109][110][111] Evidence of this possibility includes the satellite's salt-rich particles having an "ocean-like" composition that indicates most of Enceladus's expelled ice comes from the evaporation of liquid salt water.[112][113][114] A 2015 flyby by Cassini through a plume on Enceladus found most of the ingredients to sustain life forms that live by methanogenesis.[115]

In April 2014, NASA scientists reported the possible beginning of a new moon within the A Ring, which was imaged by Cassini on 15 April 2013.[116]

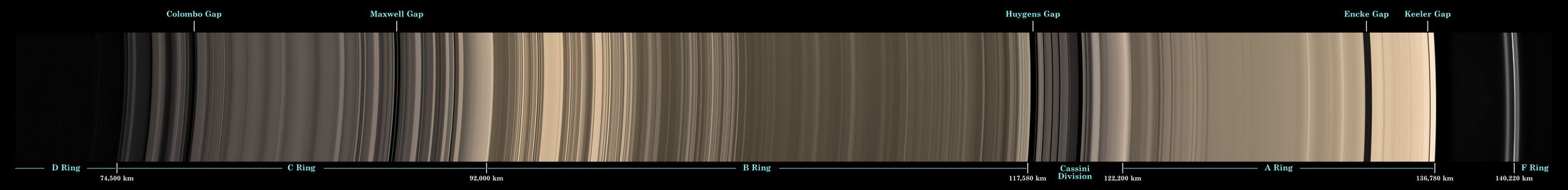

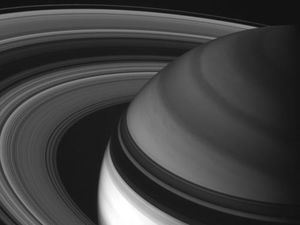

الحلقات الكوكبية

Saturn is probably best known for the system of planetary rings that makes it visually unique.[43] The rings extend from 6,630 to 120,700 kilometers (4,120 to 75,000 mi) outward from Saturn's equator and average approximately 20 meters (66 ft) in thickness. They are composed predominantly of water ice, with trace amounts of tholin impurities and a peppered coating of approximately 7% amorphous carbon.[117] The particles that make up the rings range in size from specks of dust up to 10 m.[118] While the other gas giants also have ring systems, Saturn's is the largest and most visible.

There are two main hypotheses regarding the origin of the rings. One hypothesis is that the rings are remnants of a destroyed moon of Saturn, for which a research team at MIT has proposed the name "Chrysalis".[119] The second hypothesis is that the rings are left over from the original nebular material from which Saturn was formed. Some ice in the E ring comes from the moon Enceladus's geysers.[120][121][122][123] The water abundance of the rings varies radially, with the outermost ring A being the most pure in ice water. This abundance variance may be explained by meteor bombardment.[124]

Beyond the main rings, at a distance of 12 million km from the planet is the sparse Phoebe ring. It is tilted at an angle of 27° to the other rings and, like Phoebe, orbits in retrograde fashion.[125]

Some of the moons of Saturn, including Pandora and Prometheus, act as shepherd moons to confine the rings and prevent them from spreading out.[126] Pan and Atlas cause weak, linear density waves in Saturn's rings that have yielded more reliable calculations of their masses.[127]

In September 2023, astronomers reported studies suggesting that the rings of Saturn may have resulted from the collision of two moons "a few hundred million years ago".[128][129]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تاريخ الرصد والاستكشاف

The observation and exploration of Saturn can be divided into three phases: (1) pre-modern observations with the naked eye, (2) telescopic observations from Earth beginning in the 17th century, and (3) visitation by space probes, in orbit or on flyby. In the 21st century, telescopic observations continue from Earth (including Earth-orbiting observatories like the Hubble Space Telescope) and, until its 2017 retirement, from the Cassini orbiter around Saturn.

الرصد قبل التلسكوب

Saturn has been known since prehistoric times,[130] and in early recorded history it was a major character in various mythologies. Babylonian astronomers systematically observed and recorded the movements of Saturn.[131] In ancient Greek, the planet was known as Φαίνων Phainon,[132] and in Roman times it was known as the "star of Saturn".[133] In ancient Roman mythology, the planet Phainon was sacred to this agricultural god, from which the planet takes its modern name.[134] The Romans considered the god Saturnus the equivalent of the Greek god Cronus; in modern Greek, the planet retains the name Cronus—باليونانية: Κρόνος: Kronos.[135]

The Greek scientist Ptolemy based his calculations of Saturn's orbit on observations he made while it was in opposition.[136] In Hindu astrology, there are nine astrological objects, known as Navagrahas. Saturn is known as "Shani" and judges everyone based on the good and bad deeds performed in life.[134][136] Ancient Chinese and Japanese culture designated the planet Saturn as the "earth star" (土星). This was based on Five Elements which were traditionally used to classify natural elements.[137][138][139]

In ancient Hebrew, Saturn is called Shabbathai.[140] Its angel is Cassiel. Its intelligence or beneficial spirit is 'Agȋȇl (بالعبرية: אגיאל),[141] and its darker spirit (demon) is Zȃzȇl (بالعبرية: זאזל).[141][142][143] Zazel has been described as a great angel, invoked in Solomonic magic, who is "effective in love conjurations".[144][145] In Ottoman Turkish, Urdu, and Malay, the name of Zazel is 'Zuhal', derived from the Arabic language (العربية: زحل).[142]

الأرصاد التلسكوبية قبل ارتياد الفضاء

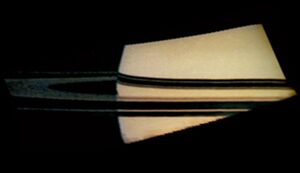

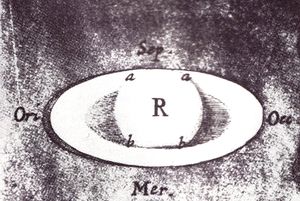

Saturn's rings require at least a 15-mm-diameter telescope[146] to resolve and thus were not known to exist until Christiaan Huygens saw them in 1655 and published about this in 1659. Galileo, with his primitive telescope in 1610,[147][148] incorrectly thought of Saturn's appearing not quite round as two moons on Saturn's sides.[149][150] It was not until Huygens used greater telescopic magnification that this notion was refuted, and the rings were truly seen for the first time. Huygens also discovered Saturn's moon Titan; Giovanni Domenico Cassini later discovered four other moons: Iapetus, Rhea, Tethys and Dione. In 1675, Cassini discovered the gap now known as the Cassini Division.[151]

No further discoveries of significance were made until 1789 when William Herschel discovered two further moons, Mimas and Enceladus. The irregularly shaped satellite Hyperion, which has a resonance with Titan, was discovered in 1848 by a British team.[152]

In 1899 William Henry Pickering discovered Phoebe, a highly irregular satellite that does not rotate synchronously with Saturn as the larger moons do.[152] Phoebe was the first such satellite found and it took more than a year to orbit Saturn in a retrograde orbit. During the early 20th century, research on Titan led to the confirmation in 1944 that it had a thick atmosphere – a feature unique among the Solar System's moons.[153]

مهام ارتياد الفضاء

تحليق پيونير 11

Pioneer 11 made the first flyby of Saturn in September 1979, when it passed within 20,000 km of the planet's cloud tops. Images were taken of the planet and a few of its moons, although their resolution was too low to discern surface detail. The spacecraft also studied Saturn's rings, revealing the thin F-ring and the fact that dark gaps in the rings are bright when viewed at a high phase angle (towards the Sun), meaning that they contain fine light-scattering material. In addition, Pioneer 11 measured the temperature of Titan.[154]

تحليق ڤويدجر

In November 1980, the Voyager 1 probe visited the Saturn system. It sent back the first high-resolution images of the planet, its rings and satellites. Surface features of various moons were seen for the first time. Voyager 1 performed a close flyby of Titan, increasing knowledge of the atmosphere of the moon. It proved that Titan's atmosphere is impenetrable at visible wavelengths; therefore no surface details were seen. The flyby changed the spacecraft's trajectory out of the plane of the Solar System.[155]

Almost a year later, in August 1981, Voyager 2 continued the study of the Saturn system. More close-up images of Saturn's moons were acquired, as well as evidence of changes in the atmosphere and the rings. Unfortunately, during the flyby, the probe's turnable camera platform stuck for a couple of days and some planned imaging was lost. Saturn's gravity was used to direct the spacecraft's trajectory towards Uranus.[155]

The probes discovered and confirmed several new satellites orbiting near or within the planet's rings, as well as the small Maxwell Gap (a gap within the C Ring) and Keeler gap (a 42 km-wide gap in the A Ring).

المركبة الفضائية كاسيني-هويگنز

The Cassini–Huygens space probe entered orbit around Saturn on 1 July 2004. In June 2004, it conducted a close flyby of Phoebe, sending back high-resolution images and data. Cassini's flyby of Saturn's largest moon, Titan, captured radar images of large lakes and their coastlines with numerous islands and mountains. The orbiter completed two Titan flybys before releasing the Huygens probe on 25 December 2004. Huygens descended onto the surface of Titan on 14 January 2005.[157]

Starting in early 2005, scientists used Cassini to track lightning on Saturn. The power of the lightning is approximately 1,000 times that of lightning on Earth.[158]

In 2006, NASA reported that Cassini had found evidence of liquid water reservoirs no more than tens of meters below the surface that erupt in geysers on Saturn's moon Enceladus. These jets of icy particles are emitted into orbit around Saturn from vents in the moon's south polar region.[159] Over 100 geysers have been identified on Enceladus.[156] In May 2011, NASA scientists reported that Enceladus "is emerging as the most habitable spot beyond Earth in the Solar System for life as we know it".[160][161]

Cassini photographs have revealed a previously undiscovered planetary ring, outside the brighter main rings of Saturn and inside the G and E rings. The source of this ring is hypothesized to be the crashing of a meteoroid off Janus and Epimetheus.[162] In July 2006, images were returned of hydrocarbon lakes near Titan's north pole, the presence of which were confirmed in January 2007. In March 2007, hydrocarbon seas were found near the North pole, the largest of which is almost the size of the Caspian Sea.[163] In October 2006, the probe detected an 8,000 km diameter cyclone-like storm with an eyewall at Saturn's south pole.[164]

From 2004 to 2 November 2009, the probe discovered and confirmed eight new satellites.[165] In April 2013 Cassini sent back images of a hurricane at the planet's north pole 20 times larger than those found on Earth, with winds faster than 530 km/h (330 mph).[166] On 15 September 2017, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft performed the "Grand Finale" of its mission: a number of passes through gaps between Saturn and Saturn's inner rings.[167][168] The atmospheric entry of Cassini ended the mission.

المهام المستقبلية المحتملة

The continued exploration of Saturn is still considered to be a viable option for NASA as part of their ongoing New Frontiers program of missions. NASA previously requested for plans to be put forward for a mission to Saturn that included the Saturn Atmospheric Entry Probe, and possible investigations into the habitability and possible discovery of life on Saturn's moons Titan and Enceladus by Dragonfly.[169][170]

الرصد

Saturn is the most distant of the five planets easily visible to the naked eye from Earth, the other four being Mercury, Venus, Mars and Jupiter. (Uranus, and occasionally 4 Vesta, are visible to the naked eye in dark skies.) Saturn appears to the naked eye in the night sky as a bright, yellowish point of light. The mean apparent magnitude of Saturn is 0.46 with a standard deviation of 0.34.[16] Most of the magnitude variation is due to the inclination of the ring system relative to the Sun and Earth. The brightest magnitude, −0.55, occurs near in time to when the plane of the rings is inclined most highly, and the faintest magnitude, 1.17, occurs around the time when they are least inclined.[16] It takes approximately 29.4 years for the planet to complete an entire circuit of the ecliptic against the background constellations of the zodiac. Most people will require an optical aid (very large binoculars or a small telescope) that magnifies at least 30 times to achieve an image of Saturn's rings in which clear resolution is present.[43][146] When Earth passes through the ring plane, which occurs twice every Saturnian year (roughly every 15 Earth years), the rings briefly disappear from view because they are so thin. Such a "disappearance" will next occur in 2025, but Saturn will be too close to the Sun for observations.[171]

Saturn and its rings are best seen when the planet is at, or near, opposition, the configuration of a planet when it is at an elongation of 180°, and thus appears opposite the Sun in the sky. A Saturnian opposition occurs every year—approximately every 378 days—and results in the planet appearing at its brightest. Both the Earth and Saturn orbit the Sun on eccentric orbits, which means their distances from the Sun vary over time, and therefore so do their distances from each other, hence varying the brightness of Saturn from one opposition to the next. Saturn also appears brighter when the rings are angled such that they are more visible. For example, during the opposition of 17 December 2002, Saturn appeared at its brightest due to a favorable orientation of its rings relative to the Earth,[172] even though Saturn was closer to the Earth and Sun in late 2003.[172]

From time to time, Saturn is occulted by the Moon (that is, the Moon covers up Saturn in the sky). As with all the planets in the Solar System, occultations of Saturn occur in "seasons". Saturnian occultations will take place monthly for about a 12-month period, followed by about a five-year period in which no such activity is registered. The Moon's orbit is inclined by several degrees relative to Saturn's, so occultations will only occur when Saturn is near one of the points in the sky where the two planes intersect (both the length of Saturn's year and the 18.6-Earth year nodal precession period of the Moon's orbit influence the periodicity).[173]

الاكتشاف

كان أول من رصد زحل غاليليو Galileo عام 1610 بوساطة مقرابه البدائي الصغير. وقد لاحظ مظهره الشاذ، الذي أربكه وحيّره. كانت الأرصاد المبكرة التي أجريت له معقدة لكون الأرض تمر عبر مستوي حلقات زحل كل بضع سنوات، لذا كانت تطرأ على صورته، ذات قوة الفصل (الميز) resolution الضعيفة، تغيرات شديدة. لم تكتشف حلقاته إلاّ عام 1659 من قبل هويغنز Huygens، وبقيت الحلقات الوحيدة المعروفة في النظام الشمسي حتى عام 1977 حين اكتُشفت حلقات باهتة اللون حول أورانوس، وبعد ذلك، بمدة قصيرة، حول المشتري ونبتون.

كان أول من زار زحل السفينة الفضائية بيُونير Pioneer 11 عام 1979، وفيما بعد السفينتان الفضائيتان فويجر Voyager1، وفويجر 2. وقد وصلت إليه السفينة كاسيني Cassini في شهر تموز عام 2004.

معلومات عن كوكب زحل

المدار: 1.429.400.00 كم أي 9054 (AU) من الشمس

القطر: 120.536 km (إستوائي)

الكتلة: 5.68e26 kg

لدى النظر إلى زحل بمقراب، يبدو مفلطحاً. وقد تبيّن أن قطره الاستوائي يكبر قطره القطبي بنسبة 10% (القطر الاستوائي: 120536 كيلومتراً، والقطبي: 108728 كيلومتراً)، ومن ثم فهو الأكثر تفلطحاً بين كواكب النظام الشمسي.

زحل أقل الكواكب كثافة، إذ إن كثافته المتوسطة 0.69 غرام/سم3، ومن ثم فهو أقل كثافة من الماء. وكما هي الحال في المشتري، فإن 75% منه هدروجين، 25% هيليوم ومقادير ضئيلة من الماء والميثان والأمونيا والصخور. تركيز الهيليوم في الجو الخارجي لزحل أعلى قليلاً من تركيز الهدروجين. القسم الداخلي فيه مكوّن من قلب صخري تعلوه طبقة من الهدروجين المعدني السائل والجزيئي. هذا القسم حار (12000 درجة مئوية)، وزحل يشع طاقة في الفضاء أكثر مما يتلقى من الشمس.

اكتشفت بعثة بيونير أن الحقل المغنطيسي لزحل أقوى بزهاء ألف مرة مما هو على الأرض، لكنه أضعف بنحو عشرين مرة مما هو على المشتري. ومثلما هي الحال في حقلي الأرض والمشتري، فمن المعتقد أن حقل زحل مولّد من الدوران البطيء للمادة الموصلة كهربائياً الموجودة داخل زحل. في زحل والمشتري، هذه المادة هي الهدروجين المعدني السائل؛ أما في الأرض فهي الحديد المصهور. هذا وإن قوة حقل زحل في أعالي غيوم الكوكب قريبة من قوة حقل الأرض على سطحها. ويتفرد حقل زحل المغنطيسي بأن محوره الشمالي-الجنوبي يمتد موازياً لمحور دوران الكوكب، خلافاً لجميع الحقول المعروفة للكواكب الأخرى. وربما تستدعي هذه الحقيقة إيجاد تفاسير جديدة لتكوّن الحقول. هذا وإن مركز حقل زحل يبعد قرابة 2400 كيلومتر باتجاه الشمال عن مركز الكوكب، ثم إن الحقل على أعالي غيومه يتجه جنوباً، خلافاً لما عليه الحال في الأرض.

بين سطحي زحل والمشتري الكثير من التشابهات، لكن لونيهما متباينان عموماً، ويُعتقد بأن السبب هو كون زحل أبرد من المشتري (لأنه أبعد منه عن الشمس)، ومن ثم فإن التفاعلات الكيميائية مختلفة فيهما، وهذا يؤدي إلى لونين مختلفين.

ويُرى على السطح خلايا إعصارية مضادة anticyclonic كبيرة الحجم، يبدو أن مصدرها المنبع الحراري الداخلي للكوكب، لكن كبرها لا يضاهي كبر البقعة الحمراء الضخمة Great Red Spot الموجودة على المشتري.

في عام 1990 أخذ مقراب هابل الفضائي Hubble Space Telescope صوراً لبقعة تمتد حول الكوكب كله، وقد أطلق عليها اسم البقعة البيضاء الضخمة Great White Spot.

ثمة رياح في جو الكوكب تهب بسرعات عالية جداً. وقد قيست سرعات هذه الرياح ووجد أنها تبلغ 1800كم/ساعة. وهذا يتجاوز أعلى سرعات الرياح في جو المشتري بأربع مرات.

في السماء الليلية، يمكن رؤية زحل بالعين المجردة. ومع أن سطوعه أضعف من سطوع المشتري، فمن السهل الحكم بأنه كوكب، لأنه لا «يتلألأ» كما تفعل النجوم. أما حلقاته وأقماره الكبيرة، فتُرى بوساطة مقراب فلكي صغير. وثمة مواقع عنكبوتية Web sites كثيرة تبين المكان الحالي لزحل (وكواكب أخرى) في السماء. و يتميز زحل بعدد كبير من الاقمار تبلغ 63 قمراً ويفوق كتلة وحجم الأرض بعدة اضعاف كما انه ثاني أكبر كواكب المجموعة الشمسية و هو ضمن الكواكب الاربعة الغازية.

من هذه الأقمار ميماس وأنسيلادوس وتيثيس وديوني وريا وتيتانو وتيتان وهايپريون وأياپتوس وفيبي.

الرصد التاريخي لكوكب زحل

زحل كان معروفاً منذ العصور التاريخية القديمة. جاليليو كان من الأوائل الذين رصدوه بتليسكوب في 1610 ، لقد لاحظ ظهوره الفردي ولكنه كان مشوشا بذلك. المراقبات الاولية لكوكب زحل كانت صعبة بعض الشيء وذلك لان الأرض تعبر خلال مستوى حلقات زحل في بعض السنين عندما يتحرك في مداره. وبسببها تنتج صورة ذات وضوح قليل لكوكب زحل. قام العالم كرستيان هويگنز Christian Huygens في العام 1659 باكتشاف حلقة و صفها [أنها حلقة غير ملاصقة بالكوكب و مائلة عن مستوى مداره و منذئذ اشتهر كوكب زحل بكونه الكوكب الوحيد المحاط بحلقات حتى عام 1977 عندما اكتشفت حلقات رقيقة حول كوكب اورانوس وبعد ذلك بفترة بسيطة حول المشتري و نبتون و في عام 1675 إكتشف الفلكي الفرنسي كاسيني أن الحلقة التي راها كاسيني مقسمة إلى قسمين متساوين بخطين متساويين بخط معتم يسمى هذا الخط حاليا بخط تقسيم كاسيني و في عام 1850 تم إكتشاف حلقة جديد أقرب إلى الكوكب من سابقتيها و أكثر إعتاما و في عام 1979 إكتشف فلكيون فرنسيون حلقة جديدة أخرى أبعد من سابقاتها عن زحل .

أول زيارة لكوكب زحل كانت باستخدام بيونير11 في عام 1979 وبعد ذلك ب فويجير 1 و فويجير 2 ثمّ كاسيني-هويگنز في عام 2004.

سوف يجد الراصد زحل مفلطحا عند استخدامه تليسكوبا صغيرا. و توجد نفس هذه الخاصية عند الكواكب الاخرى ولكن ليس بنفس المقدار. وكثافة كوكب زحل هي الاقل بين الكواكب ، بل هي اقل من كثافة الماء ، وتساوي (0.69).

التكوين الداخلي لكوكب زحل قريب من تكوين كوكب المشتري والمتكون من قالب صخري ، طبقة هيدروجينية معدنية سائلة ، و طبقة هيدروجينية جزيئية. هناك اثار لوجود كميات من الجليد المتفرقة. كوكب زحل حار جدا (12000كيلفن في المركز).

زحل يطلق كمية من الاشعة إلى الخارج أكثر من الاشعة التي يستقبلها من الشمس.

مداره

يدور زحل حول الشمس في مدار بيضاوي ويتراوح بعده عنها بين 1,508,900,000 كم عند أبعد نقطة منها و1,349,900,000 كم عند أقرب نقطة. وتستغرق دورة زحل حول الشمس 10,759 يوماً أرضياً أي حوالي 29,5 سنة أرضية. وذلك مقابل 365 يوماً أي سنة أرضية واحدة بالنسبة لدورة الأرض حول الشمس.

دورانه حول محوره

كما يدور زحل حول الشمس، فإنه يدور حول محوره. والمحور خط وهمي يمر بمركز الجسم. ومحور زحل ليس عمودياً على مداره أي لايكمل 90° درجة معه ولكن يميل بمقدار 27° درجة عن الوضع العمودي على المدار. يأتي زحل بعد المشتري من حيث سرعة دورانه. يدور زحل حول محوره مرة كل عشر ساعات وتسع وثلاثين دقيقة مقابل 24 ساعة تدورها الأرض حول محورها. وينتج عن الدوران السريع لهذا الكوكب انبعاج عند خط استوائه وتفلطح عند قطبيه. ولذلك يزيد قطره عند خط الاستواء بمقدار 13,000كم عن قطره بين القطبين.

السطح والجو

يعتقد معظم العلماء أن زحل كرة ضخمة من الغاز بدون سطح صلب. ولكن يبدو أن لهذا الكوكب قلبًا داخليًا صلبًا ساخنًا، يتكون من الحديد والمواد الصخرية. ويحيط بهذا القلب المركزي الكثيف غلاف يتكون غالباً من النشادر والميثان والماء. ويحيط بذلك غلاف آخر من الهيدروجين الفلزي المسال تحت ضغط شديد جداً، تعلوه طبقة من الهيليوم والهيدروجين المضغوطين على هيئة سائل شديد اللزوجة، يتبخر جزء منه بالقرب من سطح الكوكب. وينتشر هذا المخلوط الغازي حول زحل ليكون غلافه الجوي الذي يتكون غالباً من نفس العنصرين (هيليوم وهيدروجين).

تغطي كوكب زحل طبقة كثيفة من السُحب. وتكشف الصور الفوتوغرافية للكوكب عن وجود سلسلة من الأحزمة والمناطق ذات الألوان المتغيرة على قمم تلك السُحب. ويرجع ظهور تلك المناطق الملونة إلى اختلاف درجات الحرارة في الكتل الغازية المتفاوتة الارتفاع عن سطح الكوكب. ولاتستطيع النباتات أو الحيوانات الأرضية الحياة على سطح كوكب زحل. بل يشك العلماء في إمكانية وجود أي صورة من صور الحياة على هذا الكوكب.

مكونات الغلاف الجوي

97 % هيدروجين

3 % هيليوم

0.05 % ميثان

القياس و الابعاد

طول قطر هذا الكوكب الاستوائي 120.536 وطول قطره القطبي 108.728 ، وهذا الفرق بين القطرين الذي يصل إلى 9.8% يعود سببه إلى السرعة العالية التي يدور بها الكوكب حول محوره وأيضا إلى طبيعة العناصر المكونة لهذا الكوكب. اغلب العناصر المكونة لهذا الكوكب عبارة عن سائل فعندما يدور هذا الكوكب حول محورة تتجه مادة هذا الكوكب نحو خط الاستواء ونتيجة لذلك يتسع قطر استواء هذا الكوكب.

الكتلة و الكثافة

كتلة زحل تقدر بـ 5.69*10^26 كغ ومع ذلك فان كثافة هذا الكوكب قليلة وهو اقل كثافة بالنسبة للكواكب الأخرى ، حيث تبلغ كثافته 0.69 جم/سم وبالمقارنة بكثافة الماء التي تبلغ حوالي 1جم/سم لو وضع كوكب زحل في محيط من الماء فانه سيطفو.

زحل أقل كواكب المجموعة الشمسية كثافة حيث تبلغ كثافته (1/10) كثافة الأرض وثلثي كثافة الماء. ومعنى ذلك أن قطعة من زحل سوف تطفو على سطح الماء، وتكون أخف كثيراً من قطعة من الأرض مساوية لها في الحجم. وعلى الرغم من صغر كثافة مادة زحل، إلاَّ أن كتلته أكبر من كتلة أي كوكب آخر في المجموعة ما عدا كوكب المشتري.

تبلغ كتلة زحل 95 مرة قدر كتلة الأرض، ولكن قوة جاذبيته أكبر قليلاً من جاذبية الأرض، فالجسم الذي يزن على الأرض 45 كجم، سوف يزن 48كجم على كوكب زحل.

تركيب الغلاف الجوي

الغلاف الجوي لهذا الكوكب يتكون من 97% هيدروجين و 3.6% هليوم 0.05% ميثان . أما بالنسبة لمكوناته الأخرى فهي عبارة عن جزيئات تحتوي على ديتيريوم (خليط من الأوكسجين و النيتروجين) وامونيا و ايثانو ايثلين و فوسفين . كما تجد هنا طبقة سميكة من الضباب حول هذا الكوكب .

الحرارة

تنشأ الفصول واختلاف درجات الحرارة نتيجة لميل محور زحل إلى اتجاه الدوران حول الشمس، مما يؤدي إلى اختلاف كمية الحرارة التي تصل من الشمس إلى النصف الشمالي من الكوكب عن الحرارة التي تصل إلى النصف الجنوبي منه. ولما كان زمن دورة زحل حول الشمس أطول من زمن دورة الأرض حول الشمس بكثير (حوالي 29 مرة)، فإن الفصول على زحل تكون أطول من مثيلتها على الأرض. ويستمر الفصل الواحد على زحل 7,5 سنة أرضية تقريباً. ولما كان زحل أكثر بعداً عن الشمس فإن درجة حرارته تنخفض كثيراً عن درجة حرارة الأرض. ويبلغ متوسط درجة الحرارة على قمم السُحب التي تغطي زحل 178°م تحت الصفر (-178°م).

ولكن درجة حرارة زحل تحت طبقة السُحب أعلى بكثير منها فوق القمم، ويفقد زحل مقدارًا من الحرارة التي تتسرب من باطنه أكبر من مقدار الحرارة التي يكتسبها من الشمس (الحرارة المفقودة ضعفان ونصف ضعف الحرارة المكتسبة). ويعتقد الفلكيون أن معظم الحرارة الداخلية للكوكب تأتي من الطاقة التي يفقدها الهيليوم المسال عندما يغوص ببطء في الهيدروجين المسال في باطن الكوكب. (المعروف أن الهيليوم أكثف من الهيدروجين، كما أن درجة حرارة إسالته أعلى بكثير من درجة حرارة الهيدروجين المسال ومن ثم تنطلق الحرارة منه عندما يبرد إلى درجة حرارة الهيدروجين).

الطقس

تصل سرعة الرياح على سطح هذا الكوكب إلى 500م/ث حيث يكون اتجاه هذا الرياح في اتجاه الشرق هذا عند خط الاستواء أما في المناطق الأخرى فيكون اتجاه الريح على حسب المنطقة.

أيام و سنين زحل

يدور زحل حول نفسه كل 11 ساعة تقريبا وهذا هو اليوم بالنسبة له ، ويدور حول الشمس كل 29.46 سنه أرضية أي أن سنة زحل ب29.46 سنة من سنوات الأرض .

حلقات زحل

مقالة مفصلة: حلقات زحل

مقالة مفصلة: حلقات زحل

تحيط حلقات زحل بالكوكب عند خط استوائه، ولكنها لا تمسه. وتميل الحلقات على مدار الكوكب حول الشمس بنفس زاوية ميل محوره على المدار. وتحتوي الحلقات السبع الرئيسية على آلاف الحليقات الضيقة التي تتكون بدورها من بلايين من قطع البَرَد التي يتراوح حجمها بين حجم ذرات الغبار وقطع كبيرة، يزيد قطر الواحدة منها على ثلاثة أمتار. والحلقات الرئيسية عريضة جداً، حيث يصل عرض الحلقة الخارجية مثلاً إلى 300,000 كم. ولكن هذه الحلقات رقيقة، لدرجة أنه لايمكن رؤيتها إذا كان سمكها على خط الرؤية من الأرض. ويتراوح سمك حلقات زحل بين 200م و3,000م. وهي منفصلة بعضها عن بعض بفجوات من الفراغ يصل عرضها إلى 200،3كم أو أكثر. وبعض هذه الفجوات يحتوي على حُلَيْقَات قليلة من البرد.

وقد اكتُشفت حلقات زحل في أوائل القرن السابع عشر على يدي الفلكي الإيطالي گاليليو. ولم يستطع جاليليو رؤية الحلقات بوضوح بوساطة تلسكوبه الصغير وظن أنها أقمار كبيرة أو توابع لزحل. وبعد فحص الحلقات بتلسكوب أكبر سنة 1656، وصفها الفلكي الهولندي كريستيان هويگنز بأنها حلقة منبسطة رقيقة حول زحل. وظن هايجنز أنها حلقة من مادة صلبة. وفي عام 1675، أعلن الفلكي الفرنسي جان دومينيك كاسيني أنه اكتشف حلقتين منفصلتين حول زحل، تتكون كل منهما من أسراب من التوابع أو الأقمار الصغيرة. ثم توالى بعد ذلك اكتشاف باقي الحلقات الرئيسية. أما الحليقات فلم تكتشف إلا سنة 1980.

وصول الانسان إلى زحل

كوكب زحل يختلف عن الكرة الأرضية بحيث أننا لا نستطيع أن نحيا علية وذلك للأسباب التالية:

1 - الرياح سريعة على الكوكب وتبلغ 1800 كم/س

2 - الضغط الجوي عالي جداً

3 - عدم وجود أرض صلبة

الغيوم و السّفيّات Spokes

عدة بقع سوداء مميزه يمكن أن ترى عبرالحلقة B على يسار الكوكب. القمر ( Rhea ) و القمر (Dione ) يظهران كنقاط اسفل إلى يسار الكوكب زحل على التوالي . هذه الصورة قد أخذت في تموز\ يوليو 1981،21 عندما كانت المركبة الفضائية على بعد 33.9 مليون كيلومتر عن الكوكب المركبة (Voyager 2 ) اقتربت أكثر من زحل في أغسطس 1981.25 .

توابع (أقمار) زحل

يتبع زحل مالايقل عن 18 تابعًا بالإضافة إلى حلقاته. والتابع تيتان هو أكبر توابع زحل ويبلغ قطره 5,140 كم، ويكون بذلك أكبر من كوكب عطارد، وأكبر من كوكب بلوتو. وتيتان هو أحد التوابع القليلة في المجموعة الشمسية الذي يحيط به غلاف جوي. ويتكون غلافه الجوي أساساً من غاز النيتروجين.

وتوجد أغوار على هيئة فوهات في كثير من توابع زحل. فهناك فوهة كبيرة تغطي ثلث سطح التابع ميماس. أما التابع إيابيتوس فيظهر نصفه ساطعاً ونصفه الآخر مظلمًا، حيث يعكس النصف الساطع من ضوء الشمس عشرة أضعاف مايعكسه النصف الداكن منه. ويختلف شكل التابع هيبريون عن باقي توابع زحل. فهو على هيئة أسطوانية قصيرة وليس على هيئة كرة. كما أن محور هيبريون لا يتجه نحو زحل.

وفي عامي 1980، 1981م، وأثناء إجراء التجارب بوساطة المسار الفضائي فوياجير، التُقِطَت صور غير واضحة تشير إلى إمكانية وجود ستة توابع إضافية للكوكب زحل. ولم يتابع العلماء رصد هذه التوابع، ولذلك لم يتوفر لديهم مايؤكد وجود هذه التوابع الستة بعد. والجدول المرفق يعطي بعض المعلومات عن توابع زحل المعروفة.

رحلات إلى زحل

أطلقت الولايات المتحدة سنة 1973م مركبة فضائية غير مأهولة لارتياد كوكبي زحل والمشتري. ودارت تلك المركبة التي أطلق عليها اسم رائد زحل، حول المشتري في سنة 1974م، ثم حلقت على بعد 20,900كم من زحل في أول سبتمبر سنة 1979م. وقد أرسلت هذه المركبة بيانات علمية وصوراً فوتوغرافية لكوكب زحل أسفرت عن اكتشاف الحلقتين الخارجيتين للكوكب.

اكتشفت المركبة رائد زحل أيضاً أن لهذا الكوكب مجالاً مغنطيسياً أقوى ألف مرة من المجال المغنطيسي للأرض. وينشأ عن هذا المجال وجود قوى مغنطيسية شديدة تنتشر في منطقة كبيرة حول زحل تعرف بطبقة الغلاف المغنطيسي. وكذلك دلت البيانات العلمية المرسلة من نفس المركبة على وجود أحزمة إشعاعية داخل طبقة الغلاف المغنطيسي لكوكب زحل. وتتكون هذه الأحزمة الإشعاعية من إلكترونات وبروتونات ذات طاقات عالية جداً محبوسة داخل الغلاف المغنطيسي لزحل، على غرار أحزمة فان ألن الإشعاعية التي تحيط بالأرض. وفي عام 1977م، أطلقت الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية المركبتين الفضائيتين فويجر 1 وفويجر 2. حلقت المركبة فويجر 1 على ارتفاع 126,000كم فوق زحل. وفي أغسطس عام 1981م، حلقت المركبة فويجر 2 على ارتفاع 101,000كم فوق زحل أيضًا.

وقد أكدت هاتان الرحلتان وجود الحلقة السابعة حول زحل. كما اكتشفتا أن الحلقات الرئيسية مكونة من حليقات رفيعة. وبالإضافة إلى ذلك أرسلت، المركبتان بيانات وصوراً ضوئية أدت إلى اكتشاف تسعة من توابع زحل. كما كان لهاتين المركبتين الفضل في معرفة أن النيتروجين هو العنصر الأساسي الذي يتكون منه الغلاف الجوي للتابع تيتان (أكبر توابع زحل).

وفي 1988م، أعلنت وكالة الفضاء الأوروبية (وهي مؤسسة علمية تابعة لدول أوروبا)، أن لديها خططاً لإطلاق مركبة فضائية غير مأهولة تتجه نحو تيتان، أكبر توابع زحل، على أن تبدأ هذه الرحلة في أواخر التسعينيات من القرن العشرين الميلادي.

وفي عام 1997م، أطلقت الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية المجس كاسيني لدراسة كوكب زحل وحلقاته وتوابعه. وقد تم جدولة رحلة المجس ليصل إلى زحل عام 2004م. ويحمل المجس كاسيني المجس الأوروبي هيجنز الذي سينفصل عن كاسيني ويهبط في تيتان.

يمطر ألماساً

توصل علماء أمريكيون إلى أن أحجارا من الماس - تقارب في حجمها الأحجار الكريمة في مجوهرات نجمات السينما الأمريكية - قد تهطل على كوكبي زحل والمشتري. وأوضح العلماء أن بيانات جوية جديدة عن الكوكبين العملاقين تشير إلى وجود غاز الكربون بوفرة في شكل بلوري متلألئ. وتحوّل العواصف الرعدية غاز الميثان إلى الكربون الذي يزداد صلابة أثناء هطوله بحيث يصبح في صورة كتل من الغرافيت ثم الألماس. وأشار الباحثون خلال مؤتمر علمي إلى أن "أحجار البَرَد" من الماس تذوب في بحر سائل في مناطق ساخنة في الكوكبين. وقد يصل قطر أكبر ألماسات إلى نحو سنتيمتر "وهي كبيرة على نحو يسمح بترصيع خاتم، على الرغم من أنها ستكون في شكلها الأولي"، حسب كفن بينز، من جامعة وسكونسن-ماديسون ومختبر الدفع النفاث بوكالة الفضاء والطيران الأمريكية (ناسا).[174]

See also

ملاحظات

المصادر

المراجع

- ^ أ ب "Planetary Physical Parameters". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Simon, J.L.; Bretagnon, P.; Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G.; Laskar, J. (February 1994). "Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 663–683. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^ Souami, D.; Souchay, J. (July 2012). "The solar system's invariable plane". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: 11. Bibcode:2012A&A...543A.133S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219011. A133.

- ^ "HORIZONS Planet-center Batch call for November 2032 Perihelion". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov (Perihelion for Saturn's planet-center (699) occurs on 2032-Nov-29 at 9.0149170au during a rdot flip from negative to positive). NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ أ ب "Solar System Dynamics – Planetary Satellite Discovery Circumstances". NASA. 15 November 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Saturn now leads moon race with 62 newly discovered moons". UBC Science. University of British Columbia. 11 May 2023. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Williams, David R. (23 December 2016). "Saturn Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ "By the Numbers – Saturn". NASA Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ "NASA: Solar System Exploration: Planets: Saturn: Facts & Figures". Solarsystem.nasa.gov. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Fortney, J.J.; Helled, R.; Nettlemann, N.; Stevenson, D.J.; Marley, M.S.; Hubbard, W.B.; Iess, L. (6 December 2018). "The Interior of Saturn". In Baines, K.H.; Flasar, F.M.; Krupp, N.; Stallard, T. (eds.). Saturn in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 44–68. ISBN 978-1-108-68393-7. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Seligman, Courtney. "Rotation Period and Day Length". Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ أ ب McCartney, Gretchen; Wendel, JoAnna (18 January 2019). "Scientists Finally Know What Time It Is on Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ أ ب Mankovich, Christopher; et al. (17 January 2019). "Cassini Ring Seismology as a Probe of Saturn's Interior. I. Rigid Rotation". The Astrophysical Journal. 871 (1): 1. arXiv:1805.10286. Bibcode:2019ApJ...871....1M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaf798. S2CID 67840660.

- ^ Hanel, R.A.; et al. (1983). "Albedo, internal heat flux, and energy balance of Saturn". Icarus. 53 (2): 262–285. Bibcode:1983Icar...53..262H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(83)90147-1.

- ^ Mallama, Anthony; Krobusek, Bruce; Pavlov, Hristo (2017). "Comprehensive wide-band magnitudes and albedos for the planets, with applications to exo-planets and Planet Nine". Icarus. 282: 19–33. arXiv:1609.05048. Bibcode:2017Icar..282...19M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.023. S2CID 119307693.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Mallama, A.; Hilton, J.L. (2018). "Computing Apparent Planetary Magnitudes for The Astronomical Almanac". Astronomy and Computing. 25: 10–24. arXiv:1808.01973. Bibcode:2018A&C....25...10M. doi:10.1016/j.ascom.2018.08.002. S2CID 69912809.

- ^ "Encyclopedia - the brightest bodies". IMCCE. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ أ ب "Saturn's Temperature Ranges". Sciencing. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "The Planet Saturn". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Knecht, Robin (24 October 2005). "On The Atmospheres Of Different Planets" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ Brainerd, Jerome James (24 November 2004). "Characteristics of Saturn". The Astrophysics Spectator. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "General Information About Saturn". Scienceray. 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Brainerd, Jerome James (6 October 2004). "Solar System Planets Compared to Earth". The Astrophysics Spectator. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Dunbar, Brian (29 November 2007). "NASA – Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008). "Mass of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت Russell, C. T.; et al. (1997). "Saturn: Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere". Science. 207 (4429): 407–10. Bibcode:1980Sci...207..407S. doi:10.1126/science.207.4429.407. PMID 17833549. S2CID 41621423. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ^ "MPEC 2023-J49 : S/2006 S 12". Minor Planet Electronic Circulars. Minor Planet Center. 7 May 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Munsell, Kirk (6 April 2005). "The Story of Saturn". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory; California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 16 August 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- ^ Jones, Alexander (1999). Astronomical papyri from Oxyrhynchus. American Philosophical Society. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9780871692337. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Falk, Michael (June 1999), "Astronomical Names for the Days of the Week", Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 93: 122–133, Bibcode: 1999JRASC..93..122F, http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu/pdf/1999JRASC..93..122F, retrieved on 18 November 2020

- ^ Melosh, H. Jay (2011). Planetary Surface Processes. Cambridge Planetary Science. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-51418-7. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Gregersen, Erik, ed. (2010). Outer Solar System: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and the Dwarf Planets. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 119. ISBN 978-1615300143. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Saturn – The Most Beautiful Planet of our solar system". Preserve Articles. 23 January 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Williams, David R. (16 November 2004). "Jupiter Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ أ ب Fortney, Jonathan J.; Nettelmann, Nadine (May 2010). "The Interior Structure, Composition, and Evolution of Giant Planets". Space Science Reviews. 152 (1–4): 423–447. arXiv:0912.0533. Bibcode:2010SSRv..152..423F. doi:10.1007/s11214-009-9582-x. S2CID 49570672.

- ^ أ ب ت Guillot, Tristan; et al. (2009). "Saturn's Exploration Beyond Cassini-Huygens". In Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (eds.). Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. p. 745. arXiv:0912.2020. Bibcode:2009sfch.book..745G. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_23. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9. S2CID 37928810.

- ^ "Saturn - The interior | Britannica". www.britannica.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- ^ Fortney, Jonathan J. (2004). "Looking into the Giant Planets". Science. 305 (5689): 1414–1415. doi:10.1126/science.1101352. PMID 15353790. S2CID 26353405. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Saumon, D.; Guillot, T. (July 2004). "Shock Compression of Deuterium and the Interiors of Jupiter and Saturn". The Astrophysical Journal. 609 (2): 1170–1180. arXiv:astro-ph/0403393. Bibcode:2004ApJ...609.1170S. doi:10.1086/421257. S2CID 119325899.

- ^ "Saturn". BBC. 2000. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Mankovich, Christopher R.; Fuller, Jim (2021). "A diffuse core in Saturn revealed by ring seismology". Nature Astronomy. 5 (11): 1103–1109. arXiv:2104.13385. Bibcode:2021NatAs...5.1103M. doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01448-3. S2CID 233423431. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Faure, Gunter; Mensing, Teresa M. (2007). Introduction to planetary science: the geological perspective. Springer. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-4020-5233-0. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Saturn". National Maritime Museum. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ "Structure of Saturn's Interior". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ de Pater, Imke; Lissauer, Jack J. (2010). Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0-521-85371-2. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "NASA – Saturn". NASA. 2004. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (9 October 2013). "Diamond Rain May Fill Skies of Jupiter and Saturn". Space.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Kaplan, Sarah (25 August 2017). "It rains solid diamonds on Uranus and Neptune". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Saturn". Universe Guide. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ^ Guillot, Tristan (1999). "Interiors of Giant Planets Inside and Outside the Solar System". Science. 286 (5437): 72–77. Bibcode:1999Sci...286...72G. doi:10.1126/science.286.5437.72. PMID 10506563. S2CID 6907359.

- ^ Courtin, R.; et al. (1967). "The Composition of Saturn's Atmosphere at Temperate Northern Latitudes from Voyager IRIS spectra". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 15: 831. Bibcode:1983BAAS...15..831C.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (22 January 2009). "Atmosphere of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ أ ب Guerlet, S.; Fouchet, T.; Bézard, B. (November 2008). Charbonnel, C.; Combes, F.; Samadi, R. (eds.). "Ethane, acetylene and propane distribution in Saturn's stratosphere from Cassini/CIRS limb observations". SF2A-2008: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the French Society of Astronomy and Astrophysics: 405. Bibcode:2008sf2a.conf..405G.

- ^ Martinez, Carolina (5 September 2005). "Cassini Discovers Saturn's Dynamic Clouds Run Deep". NASA. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2007.

- ^ "Cassini Image Shows Saturn Draped in a String of Pearls" (Press release). Carolina Martinez, NASA. 10 November 2006. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ Orton, Glenn S. (September 2009). "Ground-Based Observational Support for Spacecraft Exploration of the Outer Planets". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 105 (2–4): 143–152. Bibcode:2009EM&P..105..143O. doi:10.1007/s11038-009-9295-x. S2CID 121930171.

- ^ Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (2009). Dougherty, Michele K.; Esposito, Larry W.; Krimigis, Stamatios M. (eds.). Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. Springer. p. 162. Bibcode:2009sfch.book.....D. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Pérez-Hoyos, S.; Sánchez-Laveg, A.; French, R. G.; J. F., Rojas (2005). "Saturn's cloud structure and temporal evolution from ten years of Hubble Space Telescope images (1994–2003)". Icarus. 176 (1): 155–174. Bibcode:2005Icar..176..155P. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.01.014.

- ^ Kidger, Mark (1992). "The 1990 Great White Spot of Saturn". In Moore, Patrick (ed.). 1993 Yearbook of Astronomy. London: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 176–215. Bibcode:1992ybas.conf.....M.

- ^ Li, Cheng; de Pater, Imke; Moeckel, Chris; Sault, R. J.; Butler, Bryan; deBoer, David; Zhang, Zhimeng (11 August 2023). "Long-lasting, deep effect of Saturn's giant storms". Science Advances. 9 (32): eadg9419. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adg9419. PMC 10421028. PMID 37566653.

- ^ Hamilton, Calvin J. (1997). "Voyager Saturn Science Summary". Solarviews. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ Watanabe, Susan (27 March 2007). "Saturn's Strange Hexagon". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ أ ب "Warm Polar Vortex on Saturn". Merrillville Community Planetarium. 2007. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ Godfrey, D. A. (1988). "A hexagonal feature around Saturn's North Pole". Icarus. 76 (2): 335. Bibcode:1988Icar...76..335G. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90075-9.

- ^ Sanchez-Lavega, A.; et al. (1993). "Ground-based observations of Saturn's north polar SPOT and hexagon". Science. 260 (5106): 329–32. Bibcode:1993Sci...260..329S. doi:10.1126/science.260.5106.329. PMID 17838249. S2CID 45574015.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (6 August 2014). "Storm Chasing on Saturn". New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "New images show Saturn's weird hexagon cloud". NBC News. 12 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Godfrey, D. A. (9 March 1990). "The Rotation Period of Saturn's Polar Hexagon". Science. 247 (4947): 1206–1208. Bibcode:1990Sci...247.1206G. doi:10.1126/science.247.4947.1206. PMID 17809277. S2CID 19965347.

- ^ Baines, Kevin H.; et al. (December 2009). "Saturn's north polar cyclone and hexagon at depth revealed by Cassini/VIMS". Planetary and Space Science. 57 (14–15): 1671–1681. Bibcode:2009P&SS...57.1671B. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2009.06.026.

- ^ Ball, Philip (19 May 2006). "Geometric whirlpools revealed". Nature. doi:10.1038/news060515-17. S2CID 129016856. Bizarre geometric shapes that appear at the center of swirling vortices in planetary atmospheres might be explained by a simple experiment with a bucket of water but correlating this to Saturn's pattern is by no means certain.

- ^ Aguiar, Ana C. Barbosa; et al. (April 2010). "A laboratory model of Saturn's North Polar Hexagon". Icarus. 206 (2): 755–763. Bibcode:2010Icar..206..755B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.10.022. Laboratory experiment of spinning disks in a liquid solution forms vortices around a stable hexagonal pattern similar to that of Saturn's.

- ^ Sánchez-Lavega, A.; et al. (8 October 2002). "Hubble Space Telescope Observations of the Atmospheric Dynamics in Saturn's South Pole from 1997 to 2002". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 34: 857. Bibcode:2002DPS....34.1307S. Archived from the original on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ "NASA catalog page for image PIA09187". NASA Planetary Photojournal. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ "Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn". BBC News. 10 November 2006. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ "NASA Sees into the Eye of a Monster Storm on Saturn". NASA. 9 November 2006. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- ^ أ ب قالب:Cite APOD

- ^ أ ب McDermott, Matthew (2000). "Saturn: Atmosphere and Magnetosphere". Thinkquest Internet Challenge. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ "Voyager – Saturn's Magnetosphere". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (14 December 2010). "Hot Plasma Explosions Inflate Saturn's Magnetic Field". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Russell, Randy (3 June 2003). "Saturn Magnetosphere Overview". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (26 January 2009). "Orbit of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 23 January 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Michtchenko, T. A.; Ferraz-Mello, S. (February 2001). "Modeling the 5 : 2 Mean-Motion Resonance in the Jupiter-Saturn Planetary System". Icarus. 149 (2): 357–374. Bibcode:2001Icar..149..357M. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6539.

- ^ Jean Meeus, Astronomical Algorithms (Richmond, VA: Willmann-Bell, 1998). Average of the nine extremes on p 273. All are within 0.02 AU of the averages.

- ^ Kaiser, M. L.; Desch, M. D.; Warwick, J. W.; Pearce, J. B. (1980). "Voyager Detection of Nonthermal Radio Emission from Saturn". Science. 209 (4462): 1238–40. Bibcode:1980Sci...209.1238K. doi:10.1126/science.209.4462.1238. hdl:2060/19800013712. PMID 17811197. S2CID 44313317.

- ^ Benton, Julius (2006). Saturn and how to observe it. Astronomers' observing guides (11th ed.). Springer Science & Business. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-85233-887-9. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Scientists Find That Saturn's Rotation Period is a Puzzle". NASA. 28 June 2004. Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (30 June 2008). "Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Anderson, J. D.; Schubert, G. (2007). "Saturn's gravitational field, internal rotation and interior structure" (PDF). Science. 317 (5843): 1384–1387. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1384A. doi:10.1126/science.1144835. PMID 17823351. S2CID 19579769. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-12.

- ^ "Enceladus Geysers Mask the Length of Saturn's Day" (Press release). NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 22 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Gurnett, D. A.; et al. (2007). "The Variable Rotation Period of the Inner Region of Saturn's Plasma Disc" (PDF). Science. 316 (5823): 442–5. Bibcode:2007Sci...316..442G. doi:10.1126/science.1138562. PMID 17379775. S2CID 46011210. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-12.

- ^ Bagenal, F. (2007). "A New Spin on Saturn's Rotation". Science. 316 (5823): 380–1. doi:10.1126/science.1142329. PMID 17446379. S2CID 118878929.

- ^ Hou, X. Y.; et al. (January 2014). "Saturn Trojans: a dynamical point of view". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 437 (2): 1420–1433. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.437.1420H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1974.

- ^ Ashton, Edward; Gladman, Brett; Beaudoin, Matthew (August 2021). "Evidence for a Recent Collision in Saturn's Irregular Moon Population". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (4): 12. Bibcode:2021PSJ.....2..158A. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac0979. S2CID 236974160.

- ^ Tiscareno, Matthew (17 July 2013). "The population of propellers in Saturn's A Ring". The Astronomical Journal. 135 (3): 1083–1091. arXiv:0710.4547. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1083T. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/1083. S2CID 28620198.

- ^ Brunier, Serge (2005). Solar System Voyage. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-521-80724-1.

- ^ Jones, G. H.; et al. (7 March 2008). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea" (PDF). Science. 319 (5868): 1380–1384. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J. doi:10.1126/science.1151524. PMID 18323452. S2CID 206509814. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2018.

- ^ Atkinson, Nancy (26 November 2010). "Tenuous Oxygen Atmosphere Found Around Saturn's Moon Rhea". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

- ^ NASA (30 November 2010). "Thin air: Oxygen atmosphere found on Saturn's moon Rhea". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ Ryan, Clare (26 November 2010). "Cassini reveals oxygen atmosphere of Saturn′s moon Rhea". UCL Mullard Space Science Laboratory. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Saturn's Known Satellites". Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Cassini Finds Hydrocarbon Rains May Fill Titan Lakes". ScienceDaily. 30 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Voyager – Titan". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2010. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Evidence of hydrocarbon lakes on Titan". NBC News. Associated Press. 25 July 2006. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ "Hydrocarbon lake finally confirmed on Titan". Cosmos Magazine. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ López-Puertas, Manuel (6 June 2013). "PAH's in Titan's Upper Atmosphere". CSIC. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Dyches, Preston; et al. (23 June 2014). "Titan's Building Blocks Might Pre-date Saturn". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- ^ Battersby, Stephen (26 March 2008). "Saturn's moon Enceladus surprisingly comet-like". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ NASA (21 April 2008). "Could There Be Life On Saturn's Moon Enceladus?". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis (24 June 2009). "Hunt for Life on Saturnian Moon Heats Up". Wired Science. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Spotts, Peter N. (28 September 2005). "Life beyond Earth? Potential solar system sites pop up". USA Today. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Pili, Unofre (9 September 2009). "Enceladus: Saturn′s Moon, Has Liquid Ocean of Water". Scienceray. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Strongest evidence yet indicates Enceladus hiding saltwater ocean". Physorg. 22 June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Kaufman, Marc (22 June 2011). "Saturn′s moon Enceladus shows evidence of an ocean beneath its surface". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Greicius, Tony; et al. (22 June 2011). "Cassini Captures Ocean-Like Spray at Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Chou, Felicia; Dyches, Preston; Weaver, Donna; Villard, Ray (13 April 2017). "NASA Missions Provide New Insights into 'Ocean Worlds' in Our Solar System". NASA. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Platt, Jane; et al. (14 April 2014). "NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Poulet F.; et al. (2002). "The Composition of Saturn's Rings". Icarus. 160 (2): 350. Bibcode:2002Icar..160..350P. doi:10.1006/icar.2002.6967. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Porco, Carolyn. "Questions about Saturn's rings". CICLOPS web site. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Wisdom, Jack; Dbouk, Rola; Militzer, Burkhard; Hubbard, William B.; Nimmo, Francis; Downey, Brynna G.; French, Richard G. (September 16, 2022). "Loss of a satellite could explain Saturn's obliquity and young rings". Science. 377 (6612): 1285–1289. Bibcode:2022Sci...377.1285W. doi:10.1126/science.abn1234. PMID 36107998. S2CID 252310492.

- ^ Spahn, F.; et al. (2006). "Cassini Dust Measurements at Enceladus and Implications for the Origin of the E Ring" (PDF). Science. 311 (5766): 1416–1418. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1416S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.6748. doi:10.1126/science.1121375. PMID 16527969. S2CID 33554377. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Finger-like Ring Structures In Saturn's E Ring Produced By Enceladus' Geysers". CICLOPS web site. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Icy Tendrils Reaching into Saturn Ring Traced to Their Source". CICLOPS web site (Press release). 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "The Real Lord of the Rings". Science@NASA. 12 February 2002. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Esposito, Larry W.; et al. (February 2005). "Ultraviolet Imaging Spectroscopy Shows an Active Saturnian System" (PDF). Science. 307 (5713): 1251–1255. Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1251E. doi:10.1126/science.1105606. PMID 15604361. S2CID 19586373. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-18.

- ^ Cowen, Rob (7 November 1999). "Largest known planetary ring discovered". Science News. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Russell, Randy (7 June 2004). "Saturn Moons and Rings". Windows to the Universe. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (3 March 2005). "NASA's Cassini Spacecraft Continues Making New Discoveries". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ Andrew, Robin George (28 September 2023). "Saturn's Rings May Have Formed in a Surprisingly Recent Crash of 2 Moons - Researchers completed a complex simulation that supports the idea that the giant planet's jewelry emerged hundreds of millions of years ago, not billions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Teodoro, L.F.A.; et al. (27 September 2023). "A Recent Impact Origin of Saturn's Rings and Mid-sized Moons". The Astrophysical Journal. 955 (2). doi:10.3847/1538-4357/acf4ed. Archived from the original on 29 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Observing Saturn". National Maritime Museum. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- ^ Sachs, A. (2 May 1974). "Babylonian Observational Astronomy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 276 (1257): 43–50. Bibcode:1974RSPTA.276...43S. doi:10.1098/rsta.1974.0008. JSTOR 74273. S2CID 121539390.

- ^ Φαίνων. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum.

- ^ أ ب "Starry Night Times". Imaginova Corp. 2006. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ "Greek Names of the Planets". 25 April 2010. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

The Greek name of the planet Saturn is Kronos. The Titan Cronus was the father of Zeus, while Saturn was the Roman God of agriculture.

See also the Greek article about the planet. - ^ أ ب Corporation, Bonnier (April 1893). "Popular Miscellany – Superstitions about Saturn". The Popular Science Monthly: 862. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ De Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1912). Religion in China: universism. a key to the study of Taoism and Confucianism. Vol. 10. G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 300. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Crump, Thomas (1992). The Japanese numbers game: the use and understanding of numbers in modern Japan. Routledge. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0415056090.

- ^ Hulbert, Homer Bezaleel (1909). The passing of Korea. Doubleday, Page & company. p. 426. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ Cessna, Abby (15 November 2009). "When Was Saturn Discovered?". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ أ ب "The Magus, Book I: The Celestial Intelligencer: Chapter XXVIII". Sacred-Text.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Saturn in Mythology". CrystalLinks.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ Beyer, Catherine (8 March 2017). "Planetary Spirit Sigils – 01 Spirit of Saturn". ThoughtCo.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "Meaning and Origin of: Zazel". FamilyEducation.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

Latin: Angel summoned for love invocations

- ^ "Angelic Beings". Hafapea.com. 1998. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

a Solomonic angel of love rituals

- ^ أ ب Eastman, Jack (1998). "Saturn in Binoculars". The Denver Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Chan, Gary (2000). "Saturn: History Timeline". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (3 July 2008). "History of Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (7 July 2008). "Interesting Facts About Saturn". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (27 November 2009). "Who Discovered Saturn?". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Micek, Catherine. "Saturn: History of Discoveries". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ^ أ ب Barton, Samuel G. (April 1946). "The names of the satellites". Popular Astronomy. Vol. 54. pp. 122–130. Bibcode:1946PA.....54..122B.

- ^ Kuiper, Gerard P. (November 1944). "Titan: a Satellite with an Atmosphere". Astrophysical Journal. 100: 378–388. Bibcode:1944ApJ...100..378K. doi:10.1086/144679.

- ^ "The Pioneer 10 & 11 Spacecraft". Mission Descriptions. Archived from the original on 30 January 2006. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ أ ب "Missions to Saturn". The Planetary Society. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2007.