حرب البشناق والكروات

| حرب البشناق والكروات Croat–Bosniak War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من حرب البوسنة and حروب اليوغسلاڤ | |||||||||

تجاه عقارب الساعة من أعلى اليمين: بقايا ستاري موست في موستار، حل محلها جسر كابلي؛ مفرزة مدفعية IFOR الفرنسية، في دورية بالقرب من موستار؛ نصب تذكاري لحرب الكروات في ڤيتز؛ نصب تذكاري لحرب البشناق في ستاري ڤيتز؛ منظر من نوڤي تراڤنيك أثناء الحرب. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| القوى | |||||||||

| 40.000–50.000 (1993)[1] | 100.000–120.000 (1993)[2] | ||||||||

حرب البشناق والكروات، هو نزاع بين جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك وجمهورية هرسك-بوسنيا الكرواتية، بدعم من كرواتيا، استمر من 18 أكتوبر 1992 حتى 23 فبراير 1994. عادة ما يشار إليها بمصطلح "حرب داخل حرب" لأنه كان جزءاً من حرب البوسنة الأكبر. عند بدايتها، كان البشناق والكروات يقاتلون في تحالف ضد الجيش الشعبي اليوغسلاڤي وجيش جمهورية صرب البوسنة. بحلول نهاية 1992، ازدادت التوترات بين البشناق والكروات. وقع أن الحوادث المسلحة بين الطرفين في أكتوبر 1992 في وسط البوسنة. استمر تحالفهم العسكري حتى أوائل عام 1993 عندما انهار تعاونهما العسكري وانخرط الحليفان السابقان في نزاع مفتوح.

اندلعت حرب البشناق والكروات في وسط البوسنة وسرعان ما انتشرت إلى الهرسك، حيث دار معظم القتال في تلك المنطقتين. كان البشناق منظمين في جيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك (ARBiH)، والكروات في مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي (HVO). بصفة عامة، كانت الحرب تتألف من صراعات متقطعة مع العديد من اتفاقيات وقف إطلاق النار. ومع ذلك، لم تكن حرباً شاملة بين البشناق والكروات وظلا متحالفين في مناطق أخرى. أثناء الحرب، اقترحت العديد من خطط السلام من قبل المجتمع الدولي، لكنها فشلت جميعاً. في 23 فبراير 1994، تم التوصل لوقف إطلاق النار، وانتهت الأعمال العدائية باتفاقية تم التوقيع عليها في واشنطن في 18 فبراير 1994، وكان مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي في ذلك الوقت قد تكبد خسائر كبيرة في الأراضي. أدت الاتفاقية إلى تأسيس اتحاد البوسنة والهرسك وعمليات مشتركة ضد القوات الصربية، التي ساعدت على تغيير كفة التوازن العسكري وإنهاء حرب البوسنة.

أدانت المحكمة الجنائية الدولية ليوغسلاڤيا السابقة 17 مسئول من مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي ومسئول من جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك، أدين ستة منهم بالمشاركة في مشروع إجرامي مشترك كان يسعى لضم أو السيطرة على المناطق ذات الأغلبية الكرواتية في البوسنة والهرسك، واثنين من مسئولي جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك لجرائم حرب ارتكبت أثناء النزاع. حكمت المحكمة الجنائية الدولية ليوغسلاڤيا السابقة بأن كرواتيا كان لها السيطرة الكاملة على مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي وأن النزاع كان دولياً..

خلفية

في نوفمبر 1991، عُقدت أول انتخابات حرة في البوسنة والهرسك، والتي أتت بالأحزاب الوطنية للسلطة. كانت تلك الأحزاب، حزب الحراك الديمقراطي، بقيادة علي عزت بگوڤيتش، الحزب الديمقراطي الصربي، بقيادة رادوڤان كرادزيتش، والاتحاد الديمقراطي للبوسنة والهرسك، بقيادة ستپان كليويتش. انتخب علي عزت بگوڤيتش رئيس المجلس الرئاسي لجمهورية البوسنة والهرسك رئيساً لجمهورية البوسنة والهرسك. وانتخب يورى پليڤان رئيساً لمجلس وزراء البوسنة والهرسك. وانتخب مومتشيلو كرايشنيك رئيساً لبرلمان البوسنة والهرسك.[3]

ستيپان كليويتش معلقاً على إقصائه.[4]

العلاقات السياسية والعسكرية

الخصوم

القوات البشناقية

كانت حكومة سراييڤو بطيئة في تنظيم قوة عسكرية فعالة. قاموا في البداية بتنظيم أنفسهم في قوة دفاع اقليمية، والتي كانت جزءاً مستقبلاً عن القوات المسلحة اليوغسلاڤية، وفي مجموعات شبه عسكرية مختلفة مثل اللواء الوطني، القبعات الخضر والبجعات السوداء. كان للبشناق اليد العليا في القوى العددية، لكنهم كانوا يفتقدون إمدادات الأسلحة والتسليح الثقيل. تشكل جيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك في أبريل 1992. كان يعتمد في بنيته على اليوغسلاڤ ووحدات الدفاع الإقليمي. كان يتضمن 13 لواء مشاة، 12 كتيبة منفصلة، كتيبة شرطة عسكرية، كتيبة مهندسين، فرقة مرافقة رئاسية.[5]

القوات الكرواتية

تشكل مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي في 8 أبريل 1992 وكان الجيش الرسمي للبوسنة والهرسك، على الرغم من أن تنظيم وتسليح القوات العسكرية الكرواتية البوسنية قد بدأ في أواخر عام 1991. كانت كل منطقة من مناطق البوسنة والهرسكة مسئولة عن الدفاع عن نفسها حتى تشكلت المناطق العملياتية الأربعة وكانت مقراتها الرئيسية في موستار، توميستلاڤگراد، ڤيتز واوراشيه. ومع ذلك، فدائماً ما كانت هناك مشكلات في تنسيق المناطق العملياتية.[6] كان عصب مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي ألويته التي تشكلت في أواخر 1992 وأوائل 1993. كان تنظيمهم وتعبئتهم العسكرية جيدة نسبياً، لكنهم لم يتمكنوا إلا من القيام بعمليات هجومية محدودة ومحلية. عادة ما كانت الألوية تنقسم إلى أربع كتائب مشاة مزودة بمدفعية خفيفة، مدافع هاون، وكتائب دعم وأخرى مضادة للدبابات. كان عدد أفراد اللواء يتراوح بين بضعة مئات إلى عدة آلاف رجل، لكن معظمها كان يضم 2.000-3.000 فرد.[7][8] في أوائل عام 1993 تشكل الحرس الوطني التابع لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي ليصبح أفضل تنظيماً بمرور الوقت، لكنهم لم بدأو بتشكيل ألوية الحرس، وحدات متحركة من الجنود المدربين، إلا في أوائل 1994.[9]

المقاتلون الأجانب

بدأ المتطوعون المسلمون من مختلف البلدان في المجيء إلى البوسنة والهرسك في النصف الثاني من عام 1992.[10] قاموا بتشكيل مجموعات قتالية عُرفت باسم المجاهدين والتي انضم إليها المسلمون البوسنيون الراديكاليون المحليون. وصلت أول مجموعة أجنبية من السعودية بقيادة أبو عبد العزيز.[11][12] زعم علي عزت بگوڤيتش وحزب الحراك الديمقراطي أنه ليس لديهم معلومات عن وحدات المجاهدين في المنطقة.[13] حصل المجاهدين على دعم مالي من إيران والسعودية. دُمجت مفرزة المجاهدين مع جيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك في أغسكس 1993. كانت قوتهم تُقدر بأكثر من 4.000 مقاتل.[11] أصبح هؤلاء المقاتلون معروفين بالفظائع التي ارتكبت ضد السكان الكروات في وسط البوسنة.[14]

تضمن المقاتلون الأجانب إلى جانب الكروات متطوعين بريطانيين بالإضافة لأعداد أخرى من المنطقة الثقافية المسيحية الغربية، وقاتل الكاثوليك والپروتستانت كمتطوعين إلى جانب الكروات. تم تنظيم المتطوعين الهولنديين، الأمريكان، الأيرلنديين، الپولنديين، الأستراليين، النيوزيلنديين، الفرنسيين، السويديين، الألمان، المجريين، النرويجيين، الكنديين والفنلنديين ضمن لواء المشاة الكرواتي (الدولي) رقم 103. كان هناك أيضاً وحدة إيطالية خاصة، فصيلة گاريبالدي.[15] وفصيلة للفرنسيين، فرقة جاك دوروا.[16] كما كان هناك متطوعون من ألمانيا والنمسا، يقاتلون في مجموعة شبه عسكرية تابعة لقوات الدفاع الكرواتية.

قاتل السويدي جاكي أركلوڤ في البوسنة وأُدين لدى عودته للسويد بارتكاب جرائم حرب. اعترف لاحقاً بارتكابه جرائم حرب ضد المدنيين البشناق في معسكرات هليودروم ودرتلي الكرواتيين كأحد أفراد القوات الكرواتية.[17]

خط زمني

المواجهات في پروزور ونوڤي تراڤنيك

The strained relations led to numerous local confrontations of smaller scale in late October 1992. These confrontations mostly started in order to gain control over military supplies, key facilities and communication lines, or to test the capability of the other side.[18] First of them was an armed clash in Novi Travnik on 18 October. It started as a dispute over a gas station that was shared by both armies. Verbal conflict escalated into an armed one in which an ARBiH soldier was killed. Fighting soon broke out in the entire town. Both the ARBiH and HVO mobilized their units in the area and erected roadblocks. Low-scale conflicts spread quickly in the region.[19][20] The situation worsened on 20 October after HVO Commander Ivica Stojak from Travnik was murdered,[19] for which the HVO accused the 7th Muslim brigade.[21]

The two forces engaged each other along the supply route to Jajce on 21 October,[22] as a result of an ARBiH roadblock at Ahmići set up the previous day on authority of the "Coordinating Committee for the Protection of Muslims" rather than the ARBiH command. ARBiH forces on the roadblock refused to let the HVO go through towards Jajce and the ensuing confrontation resulted in one killed ARBiH soldier. Two days later the roadblock was dismantled.[18] A new skirmish occurred in the town of Vitez the following day.[23] These conflicts lasted for several days until a ceasefire was negotiated by the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR).[18]

On 23 October another conflict broke out, this time in Prozor, a town in Northern Herzegovina, in a municipality of around 12,000 Croats and 7,000 Bosniaks. However, the exact circumstances that caused the outbreak are not known.[23] Most of Prozor was soon under control of the HVO, apart from the eastern parts of the municipality.[24] The HVO brought in reinforcements from Tomislavgrad that provided artillery support.[23] By 25 October they took full control of the Prozor municipality. Many Bosniaks fled from Prozor when the fighting started, but they began to return gradually a few days or weeks after the fighting had stopped.[25] After the battle many Bosniak houses were burned.[26] According to a HVO report after the battle, the HVO had 5 killed and 18 wounded soldiers. Initial reports ARBiH Municipal Defence indicated that several hundred Bosniaks were killed, but subsequent reports by the ARBiH made in November 1992 indicated eleven soldiers and three civilians were killed. Another ARBiH report, prepared in March 1993, revised the numbers saying eight civilians and three ARBiH soldiers were killed, while 13 troops and 10 civilians were wounded.[27]

On 29 October, the VRS captured Jajce due to the inability of ARBiH and HVO forces to construct a cooperative defense.[28] The VRS held the advantage in troop size and firepower, staff work, and its planning was significantly superior to the defenders of Jajce.[29] Croat refugees from Jajce fled to Herzegovina and Croatia, while around 20,000 Muslim refugees remained in Travnik, Novi Travnik, Vitez, Busovača, and villages near Zenica.[30]

By November 1992, the HVO controlled about 20 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[31] By December 1992, much of Central Bosnia was contrioled by the Croats.[32] Bosniak authorities forbade Croats from leaving towns such as Bugojno and Zenica, and would periodically organise exchanges of local Croats for Muslims.[33] On 18 December, the HVO took over power in areas that it controlled: it dissolved legal municipal assemblies, sacked mayors and local government members that were against confrontation with Bosniaks, and disarmed remaining Bosniak soldiers except for those in Posavina.[34]

اندلاع الحرب

راتكو ملاديتش، رئيس أركان الجيش الصربي، معلقاً على حرب البشناق-الكروات. [35]

Despite the October confrontation in Travnik and Prozor, and with each side blaming the other for the fall of Jajce, there were no large-scale clashes and a general military alliance was still in effect.[36] A period of rising tensions, followed by the fall of Jajce, reached its peak in early 1993 in central Bosnia.[37] The HVO and ARBiH clashed on 11 January in Gornji Vakuf, a town that had about 10,000 Croats and 14,000 Bosniaks, with conflicting reports as to how the fighting started and what caused it. The HVO had around 300 forces in the town and 2,000 in the surrounding area, while the ARBiH deployed several brigades of its 3rd Corps. A front line was established through the center of town. HVO artillery fired from positions on the hills to the southeast on ARBiH forces in Gornji Vakuf after their demands for surrender were rejected. Fighting also took place in nearby villages, particularly in Duša where a HVO artillery shell killed 7 civilians, including three children. A temporary ceasefire was soon arranged.[38][39]

As the situation calmed in Gornji Vakuf, conflict escalated in Busovača, the HVO's military headquarters in central Bosnia.[40] On 24 January 1993, the ARBiH ambushed and killed two HVO soldiers outside of the town in the village of Kaćuni.[38] On 26 January, six Croats and a Serb civilian were executed by the ARBiH in the village of Dusina near Zenica, north of Busovača.[41] The following day HVO forces blocked all roads in central Bosnia and thus stopped the transports of arms to the ARBiH. Intense fighting continued in the Busovača area, where the HVO attacked the Kadića Strana part of the town, in which numerous Bosniak civilians were expelled or killed,[42] until a truce was signed on 30 January.[43]

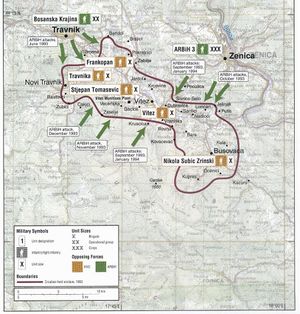

The HVO had 8,750 men in its Operative Zone Central Bosnia. The ARBiH 3rd Corps, which was based in central Bosnia, reported that during this period it had roughly 26,000 officers and men.[44] The 3:1 ratio in central Bosnia was a result of an expansion in Bosniak forces throughout 1993, which was reflected in increased arms transfers, the influx of refugees from Jajce, military-age refugees from eastern Bosnia and the arrival of fundamentalist mujahideen fighters from abroad.[45][46] By early 1993 the ARBiH also had an armaments advantage over the HVO central Bosnia.[47] This made it possible for the ARBiH to conduct offensive action on a large scale for the first time.[46] The increase in the relative power of the Bosniak side led to a change in relationship between Croats and Bosniaks in central Bosnia.[45] Despite the growing tensions, the transfer of weapons from Croatia to BiH continued throughout March and April.[48]

خطة سلام ڤانس-أوين

أبريل 1993 في وسط البوسنة

امتداد الحرب إلى الهرسك

By the end of April the Croat-Bosniak war had fully broken out. On 21 April, Šušak met with Lord Owen in Zagreb, where he expressed his anger at the behavior of Bosniaks and said that two Croat villages in eastern Herzegovina had put themselves into Serb hands rather than risking coming under Bosniak control.[49] Šušak, himself a Bosnian Croat,[28] was one of the chief supporters of Herzeg-Bosnia in the government,[50][51] and according to historian Marko Attila Hoare acted as a "conduit" of Croatian support for Bosnian Croat separatism.[28]

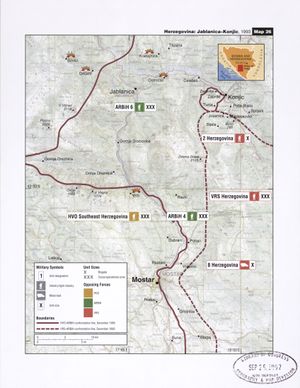

The war had spread to northern Herzegovina, firstly to the Konjic and Jablanica municipalities. The Bosniak forces in the region were organized in three brigades of the 4th Crops and could field around 5,000 soldiers. The HVO had fewer soldiers and a single brigade, headquartered in Konjic. Although there was no conflict in Konjic and Jablanica during the Croat-Bosniak clashes in central Bosnia, the situation was tense with sporadic armed incidents. The conflict started on 14 April with an ARBiH attack on a HVO-held village outside of Konjic. The HVO responded with capturing three villages northeast of Jablanica.[52] On 16 April in the village of Trusina, north of Jablanica, 15 Croat civilians and 7 POWs were killed by an ARBiH unit called the Zulfikar upon taking the village.[53] On the following day the HVO attacked the villages of Doljani and Sovići east of Jablanica. After taking control of the villages around 400 Bosniak civilians were detained until 3 May.[54] The HVO and ARBiH fought in the area until May with only several days of truce, with the ARBiH taking full control of both the towns of Konjic and Jablanica and smaller nearby villages.[52]

On 25 April, Izetbegović and Boban signed a joint statement ordering a ceasefire between the ARBiH and the HVO.[55] It declared a joint HVO-ARBiH command was created and to be led by General Halilović and General Petković with headquarters in Travnik. On the same day, however, the HVO and the HDZ BiH adopted a statement in Čitluk claiming Izetbegović was not the legitimate president of Bosnia and Herzegovina, that he represented only Bosniaks, and that the ARBiH was a Bosniak military force.[56]

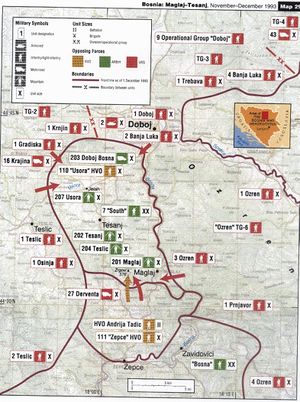

There were areas of the country where the HVO and ARBiH continued to fight side by side against the VRS. Although the armed confrontation in Herzegovina and central Bosnia strained the relationship between them, it did not result in violence and the Croat-Bosniak alliance held, particularly in places in which both were heavily outmatched by Serb forces. These exceptions were the Bihać pocket, Bosnian Posavina and the Tešanj area. Despite some animosity, an HVO brigade of around 1,500 soldiers also fought along with the ARBiH in Sarajevo.[57][58] In other areas where the alliance collapsed, the VRS, still the strongest force, occasionally cooperated with both the HVO and ARBiH, pursuing a local balancing policy and allying with the weaker side.[59]

حصار موستار

Meanwhile, tensions between Croats and Bosniaks increased in Mostar. By mid-April 1993, it had become a divided city with the western part dominated by HVO forces and the eastern part where the ARBiH was largely concentrated. While the ARBiH outnumbered the HVO in central Bosnia, the Croats held the clear military advantage in Herzegovina. The HVO headquarters was in western Mostar.[60] The 4th Corps of the ARBiH was based in eastern Mostar and under the command of Arif Pašalić.[61] The HVO Southeast Herzegovina, which had an estimated 6,000 men in early 1993, was under the command of Miljenko Lasić.[18] The conflict in Mostar started in the early hours of 9 May 1993 when both the east and west side of Mostar came under artillery fire. As in the case of Central Bosnia, there exist competing narratives as to how the conflict broke out in Mostar.[60] Combat mainly took place around the ARBiH headquarters in Vranica building in western Mostar and the HVO-held Tihomir Mišić barracks (Sjeverni logor) in eastern Mostar. After the successful HVO attack on Vranica, 10 Bosniak POWs from the building were later killed.[62] The situation in Mostar calmed down by 21 May and the two sides remained deployed on the frontlines.[63] The HVO expelled the Bosniak population from western Mostar, while thousands of men were taken to improvised prison camps in Dretelj and Heliodrom.[64] The ARBiH held Croat prisoners in detention facilities in the village of Potoci, north of Mostar, and at the Fourth elementary school camp in Mostar.[65]

On 30 June the ARBiH captured the Tihomir Mišić barracks on the east bank of the Neretva, a hydroelectric dam on the river and the main northern approaches to the city. The ARBiH also took control over the Vrapčići neighborhood in northeastern Mostar. Thus they secured the entire eastern part of the city. On 13 July the ARBiH mounted another offensive and captured Buna and Blagaj, south of Mostar. Two days later fierce fighting took place across the frontlines for control over northern and southern approaches to Mostar. The HVO launched a counterattack and recaptured Buna.[61] Both sides settled down and turned to shelling and sniping at each other, though the HVO superior heavy weaponry caused severe damage to eastern Mostar.[64] In the broader Mostar area the Serbs provided military support for the Bosniak side and hired out tanks and heavy artillery to the ARBiH. The VRS artillery shelled HVO positions on the hills overlooking Mostar.[66][67] In July 1993, Bosnian Vice President Ejup Ganić said that the biggest Bosniak mistake was a military alliance with the Croats at the beginning of the war, adding that Bosniaks were culturally closer to the Serbs.[68]

Before the war, the Mostar municipality had a population of 43,037 Croats, 43,856 Bosniaks, 23,846 Serbs and 12,768 Yugoslavs.[69] According to 1997 data, the municipalities of Mostar that in 1991 had a Croat relative majority became all Croat and municipalities that had a Bosniak majority became all Bosniak.[70] Around 60 to 75 percent of buildings in the eastern part of the city were destroyed or very badly damaged, while in the larger western part around 20 percent of buildings had been severely damaged or destroyed.[71]

هجمات يونيو–يوليو 1993

صراع تراڤنيك وكاكاني

معركة زپتشى

معركة بوگوينو

معركة بوگوينو، نشبت في 18-28 يوليو 1993 حين هجم جيش مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي (HVO) على بلدة بوگوينو بوسط البوسنة، التي كانت تحت سيطرة الجيش البوسني. فقام الجيش البوسني والمجاهدين بإلحاق هزيمة فادحة بالجيش الكرواتي. كانت منطقة بوگوينو تحت الادارة المشتركة من قبل اللواء 307 الجبلي ولواء أوگن كڤاترنيك منذ بدء حرب البوسنة. تلت الحوادث العنيفة في بوگوينو تصاعد حرب البشناق والكروات في البلديات المجاورة على مدار النصف الأول من عام 1993. تجنبت بوگوينو القتال، وكان اللوائين المحليين لا زالا متحالفين رسمياً بحلول يونيو 1993، في الوقت الذي شن فيه اللواء الجبلي هجوماً على وسط البوسنة.

اندلع القتال في البلدة في 18 يوليو. انفصلت قوات مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي، الذي كان عددهم بأكبر ثلاثة أضعاف، وطُوقوا في عدة مناطق. هُزم معظمهم في غضون أسبوع من قتال الشوارع العنيف. استسلمت آخر وحدات مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي في 25 يوليو، بينما استمر القتال في بقية البلدية لأربعة أيام أخرى. فرض الجيش البوسني سيطرته على البلدية بالكامل. خسروا 92 قتيل و211 جريح، بينما وصل عدد قتلى مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي إلى 107 قتيل و130 جريح و470 أسير. أثناء المعركة تدمر لواء أوگن كڤاترنيك بالكامل. فر حوالي 15.000 كرواتي. اعتقل عدة مئات من أسرى الحرب والمدنيين الكروات في مختلف معسكرات الاعتقال بالبلدة، ومنها استاد إسكرا. تم إطلاق سراح آخر السجناء في مارس 1994.

أدانت محكمة البوسنة والهرسك أربعة مسئولين بوسنيين ومسئول كرواتي واحد بارتكاب جرائم حرب أثناء وبعد المعركة. واتهمت المحكمة السلطات البوسنية في بوگوينو بالمشاركة في مشروع إجرامي مشترك ضد الكروات المعتقلين، وتم اسقاط التهمة في الاستئناف.

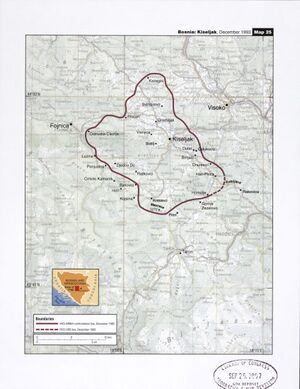

جيب كيسلياك

In July, the ARBiH was tightening its grip on Kiseljak and Busovača and pushed closer towards Vitez and Novi Travnik.[72] Due to its location on the outskirts of the besieged Sarajevo, the Kiseljak enclave was an important distribution center of smuggled supplies on the route to Sarajevo.[73] Bosniaks and Croats both wanted control over it. Until the summer, most of the fighting took place in the northern area of the enclave and west of the town of Kiseljak. During the April escalation, the HVO gained control over villages in that area. Another round of fighting started in mid June when the ARBiH attacked HVO-held Kreševo, south of Kiseljak.[74] The attack started from the south of the town and was followed by a strike on villages north and northeast of Kiseljak. The ARBiH deployed parts of its 3rd and 6th Corps, about 6–8,000 soldiers versus around 2,500 HVO soldiers in the enclave.[75] The attack on Kreševo was repelled after heavy fighting and the HVO stabilized its defence lines outside the town. The next target of the ARBiH was Fojnica, a town west of Kiseljak. The attack began on 2 July with artillery and mortar attacks, just days after the UNPROFOR Commander called the town "an island of peace". Fojnica was captured in the following days.[74]

الصراع على گورني وقف

Following the successful capture of Bugojno, the ARBiH was preparing an offensive on Gornji Vakuf, where both sides held certain parts of the town. The ARBiH launched its attack on 1 August and won control over most of the town by the following day. The HVO retained control over a Croat neighborhood in the southwest and the ARBiH, lacking necessary reinforcements, could not continue its offensive. The name of the Croat-held part was later changed to Uskoplje. The HVO attempted a counterattack from its positions to the southwest of the town on 5 August, but the ARBiH was able to repel the attack. Another attack by the HVO started in September, reinforced with tanks and heavy artillery, but it was also unsuccessful.[76]

العملية نرتڤا

خطة أوين-ستولتنبرگ

جمود الشتاء

نهاية الحرب

راسم دلتيش، القائد الأعلى لجيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك، في فبراير 1994.[48]

Beginning in 1994, the HVO was in a defensive stalemate against a progressively more organized ARBiH.[77] In January 1994, Izetbegović provided Tuđman with two different partition plans for Bosnia and Herzegovina and both were rejected.[78] In the same month, Tuđman threatened in a speech to send more HV troops into Bosnia and Herzegovina to back the HVO.[79] By February 1994, the Secretary-General of the UN reported that between 3,000 and 5,000 Croatian regular troops were in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the UN Security Council condemned Croatia, warning that if it did not end "all forms of interference" there would be "serious measures" taken.[80][81]

In February 1994, Boban and HVO hardliners were removed from power,[80] while "criminal elements" were dismissed from ARBiH.[82] On 26 February talks began in Washington, D.C., between the Bosnian government leaders and Mate Granić, Croatian Minister of Foreign Affairs, to discuss the possibilities of a permanent ceasefire and a confederation of Bosniak and Croat regions.[83] Under strong American pressure,[80] a provisional agreement on a Croat-Bosniak Federation was reached in Washington on 1 March. On 18 March, at a ceremony hosted by US President Bill Clinton, Bosnian Prime Minister Haris Silajdžić, Croatian Foreign Minister Mate Granić and President of Herzeg-Bosnia Krešimir Zubak signed the ceasefire agreement. The agreement was also signed by Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović and Croatian President Franjo Tuđman, and effectively ended the Croat–Bosniak War.[83] Under the agreement, the combined territory held by the Croat and Bosnian government forces was divided into ten autonomous cantons. According to Tuđman, Croatian support came only on the condition of American assurance of Croatia's territorial integrity, an international loan for reconstruction, membership in NATO's Partnership for Peace program, and membership in the Council of Europe. According to Western media, Tuđman received intense American pressure, including a threat of sanctions and isolation.[84]

At the end of the war, the HVO held an estimated 13% of territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the ARBiH-held territory was estimated at 21% of the country.[85] The HVO controlled some 16% before the Croat-Bosniak war.[86] In the course of the conflict, the ARBiH captured around 4% of territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the HVO, mostly in central Bosnia and northern Herzegovina. The HVO captured about 1% of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the ARBiH.[85]

Following the cessation of hostilities between Croats and Bosniaks, in late 1994 the HV intervened in Bosnia and Herzegovina against the VRS from November 1–3, in Operation Cincar near Kupres,[87] and from November 29 – December 24 in the Winter '94 operation near Dinara and Livno. These operations were undertaken to detract from the siege of the Bihać region and to approach the RSK capital of Knin from the north, isolating it on three sides.[88] By 1995, the balance of power had shifted significantly. Serb forces in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were capable of fielding an estimated 130,000 troops, while the ARBiH, HV, and HVO together had around 250,000 soldiers and 570 tanks.[89]

اتفاقية واشنطن، هي اتفاقية وقف إطلاق نار بين جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك وجمهورية هرسك-بوسنيا الكرواتية الغير معترف بها، تم التوقيع عليها في واشنطن دي سي في 18 مارس 1994 وڤيينا.[90] وقع عليها رئيس الوزراء البوسني حارس سيلايدتش، وزير الخارجية الكرواتي ماته گرانتش ورئيس هرسك-بوسنيا كرشيمير زوباك. بموجب الاتفاقية، قُسمت الأراضي المجمعة تحت سيطرة القوات الحكومية الكرواتية والبوسنية إلى عشرة كانتونات ذاتية الحكم، مؤسسة اتحاد البوسنة والهرسك. أختير نظام الكانتونات لتجنب هيمنة إحدى الجماعات العرقية على الأخرى.[بحاجة لمصدر]

دور كرواتيا

There were three phases of the engagement of regular Croatian forces in the Bosnian war. In the first phase, that lasted from spring to autumn 1992, the Croatian Army was engaged in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Bosnian Posavina, where they fought against Serb forces. This phase lasted until October 1992. The second phase was between April 1993 and May 1994, when the Croat-Bosniak conflict took place. The role of Croatia during that period remains controversial.[91] Croatia supported the Bosnian independence referendum and recognised Bosnia and Herzegovina in April 1992. It also helped arm the Bosniak forces when the Bosnian war began. However, there are different views on these moves. Croatian historian Dunja Melčić pointed out that if Croats boycotted the referendum, like the Bosnian Serbs did, Bosnia and Herzegovina would not have been recognised by the international community and become a sovereign state, and that Bosniak forces would have almost no weapons without Croatian aid.[92] Another view is that the Croatian government played up the recognition and its role in helping create the new republic while quietly Tuđman and Šušak helped Bosnian Croats reinforce and expand their autonomy.[93] American academic Sabrina P. Ramet considers that the Croatian government played a "double game" in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[78] British historian Marko Attila Hoare wrote that "a military solution required Bosnia as an ally, but a diplomatic solution required Bosnia as a victim".[94] Regarding the alleged intervention of the Croatian Army (HV), American historian Charles R. Shrader said that the actual presence of HV forces and its participation in the Croat-Bosniak conflict remains unproved.[95]

Among the explanations of the Croat-Bosniak war[96] is that the Croatian policy towards Bosnia and Herzegovina was dictated by Tuđman's personal views and his close associates, in particular the Defence Minister Gojko Šušak and the so-called Herzegovina lobby[97] The ICTY judgement against Kordic-Cerkez concludes: "President Tuđman harbored territorial ambitions in respect of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that was part of his dream of a Greater Croatia...The plan started with the HDZ in Croatia and its leader, Franjo Tuđman, and was based on the “Banovina Plan” of 1939, an agreement between Croatia and Serbia to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina between them. The Bosnian branch of the HDZ political party took over the Bosnian Croat organizations and established the Croatian community of H-B in November 1991. A campaign of persecution and ethnic cleansing was then planned and implemented by the Bosnian Croat leadership in the area of the HZ H-B, through their organizations, in particular the HVO. First they took over the government, police and military facilities in as many municipalities as possible, and asserted control over all aspects of daily life. Meanwhile, overall control was maintained by the Republic of Croatia; and the Army of the Republic (“HV”) intervened in the conflict which was thus turned into an international armed conflict with Bosnia and Herzegovina."[98]

The Croatian-American historian James J. Sadkovich claims this was as a "classic conspiracy theory".[99] In May 1990, Tuđman said that Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina "form a geographic and political whole, and in the course of history they were generally in a single united state", but suggested that its citizens should "decide their own fate through a referendum". He doubted that Bosnia and Herzegovina could survive the dissolution of Yugoslavia, but supported its integrity if it remained outside a Yugoslav federation and Serbian influence.[100] In his official statements, Tuđman advocated for an integral Bosnia and Herzegovina.[101] According to Sabrina P. Ramet, it was done in an effort to confuse foreign audiences of his intents[102] and placate the international community.[103] Tuđman supported Croatia's territorial integrity, but held that the borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina were open to negotiation.[104] His stance was emboldened by the unclear and confusing policy of the international community regarding the Bosnian war and the Serb held areas in Croatia.[105] British historian Mark Almond wrote that "almost all respectable international opinion [...] doubted the viability and legitimacy of an integral Bosnia and Herzegovina."[106] Interpretations of Tuđman's actions go from statements that he behaved as a rational opportunist,[101] to claims that he had from the outset a collaborationist policy with the Serbs on the partition of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[28] with an aim of ethnic cleansing, whereas others call that an assumption with no convincing evidence,[107][108] arguing that if Croats and Serbs had been jointly waging a war against Bosniaks, there would have been no Bosnia and Herzegovina.[109]

In the ICTY trial of Kordić & Čerkez, British diplomat Paddy Ashdown testified that Tuđman admitted to him at a meeting in London on 6 May 1995 that he and Milošević agreed on the partition of Bosnia, and Tuđman drew a map of Bosnia for Ashdown showing the proposed demarcation line; this testimony was cited by the trial judgement in 2001.[110][111]

In May 2013, in a first instance verdict against six Herzeg-Bosnia leaders, the ICTY determined that the Croat-Bosniak war was of an "international character" and found, by a majority, that "troops of the Croatian Army fought alongside the HVO against the ABiH and that the Republic of Croatia had overall control over the armed forces and the civilian authorities of the Croatian Community (and later Republic) of Herzeg-Bosna. [...] A joint criminal enterprise (JCE) existed and had as its ultimate goal the establishment of a Croatian territorial entity with part of the borders of the Croatian Banovina of 1939 to enable a reunification of the Croatian people. This Croatian territorial entity in BiH was either to be united with Croatia following the prospective dissolution of BiH, or become an independent state within BiH with direct ties to Croatia."[112] It found that Tuđman, Šušak, Boban, and others had "joined, participated in and contributed to the JCE".[113] Judge Jean-Claude Antonetti, the presiding judge in the trial, issued a separate opinion in which he contested the notion of a joint criminal enterprise. He characterized the war as a conflict of an internal nature between the Bosnian Croats and the Bosniaks and said that Tuđman's plans regarding Bosnia and Herzegovina were not in contradiction with the stance of the international community.[114] On 19 July 2016, the Appeals Chamber determined "that findings of criminal responsibility made in a case before the Tribunal are binding only on the accused in a specific case" and concluded that the "Trial Chamber made no explicit findings concerning [Tudjman's, Šušak's and Bobetko's] participation in the JCE and did not find [them] guilty of any crimes."[115]

On 29 November 2017, the ICTY Appeals Chamber issued its final judgment, reiterating and confirming the Trial Chanber's finding of a Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE) between the HZ H-B leaders and Franjo Tudjman,[116] The Appeals Chamber confirmed as correct the Trial Chamber's findings of specific elements of this JCE including: (1) that Tudjman intended to divide Bosnia and intervened in Bosnia with the aim of creating a Greater Croatia (2) that Tudjman controlled Herceg-Bosnia's military activities due to "a joint command structure”,(3) that Tudman pursued a "two-track policy", i.e. , publicly advocating respect for the existing BiH borders, while privately supporting the partition of BiH between Croats and Serbs.[116]

التبعات

فرانيو تودجمان، 24 نوفمبر 1995، في لقاء مع ممثلي هرسك-بوسنة.[117]

الخسائر

تدمير التراث الثقافي

صاحب التطهير العرقي للبوشناق على يد مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي تدمير واسع النطاق للتراث الثقافي الديني الإسلامي والثقافي.[118] شارك مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي في التدمير المتعمد للمباني الإسلامي دون نية في التحقيق مع المسئولين عن فعل ذلك.[119] إجمالاً، أعطب أو دمّر المتطرفون الكروات 201 مسجداً في الحرب.[120] على النقيض فقد اتبع جيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك سياسات/توجهات سلمية تجاه الممتلكات الدينية للتجمعات المسيحية، وقاموا بالتحقيق في مثل هذه الهجمات، وحاولوا الحفاظ على وجودها قدر الإمكان.[119] لم تكن هناك سياسة للحكومة البوسنية بتدمير الكناسئس الكاثوليكية (أو الأرثوذكسية الصربية) وظلت معظم تلك المباني الواقعة تحت سيطرة جيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك على حالها أثناء الحراب.[121]

|

|

إرهاب ما بعد الحرب

أثيرت قضية الإرهاب في البوسنة والهرسك عقب توقيع اتفاقية دايتون، بالتركيز على قضايا قتل وتفجير أشخاص معينين، معظمهم كروات.[محل شك] المجاهدون الذين استقروا في البوسنة خلقوا مناخاً من الخوف لدى الكروات والصرب في وسط البوسنة، حيث اِتـُّهـِموا باستمرار بالقيام باطلاق النار على منازل الكروات وتفجيرها والقيام بهجمات على الكروات العائدين لمنازلهم بعد الحرب.[124][125] في صيفي 1997 و 1998، قـُتـِل رجلا شرطة كروات على أيدي مجاهدين سابقين يتمتعون بحماية من الشرطة المحلية.[124]

وفي 18 سبتمبر 1997 جرى هجوم ارهابي في موستار. فقد انفجرت سيارة مفخخة أمام مركز شرطة في الجزء الغربي من المدينة، فجرحت 29 شخصاً. وقد قيل أن الهجوم قام به متطرفون إسلاميون ينتمون لتنظيم القاعدة.[126][125]

كما جرى هجوم إرهابي في كرواتيا. ففي 20 أكتوبر 1995، حاول متطرف من الجماعة الإسلامية المصرية أن يدمر محطة شرطة في رييكا بقيادة سيارة مفخخة للارتطام بجدار المبنى. أسفر الهجوم عن 29 مصاب ومقتل منفذ الهجوم. دافع الهجوم كان أسر ميليشيات HVO للمجاهد طلعب فؤاد قاسم، العضو البارز في الجماعة الإسلامية.[127] لم تحدث هجمات منذ ذلك الحين.[128]

محاكمات جرائم الحرب

أدانت المحكمة الجنائية ليوغسلاڤيا السابقة تسعة مسئولين من أعضاء مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي وجيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك بارتكاب جرائم حرب في وسط البوسنة. زلاتكو ألكسوڤسكي، قائد مرفق سجون في كاونيك، حُكم عليه بالسجن سبع سنوات لسوء معاملته المحتجزين البشناق.[129] في يوليو 2000 حُكم على القائد المحلي لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي أنتو فوروندزيا بالسجن 10 سنوات لانتهاكات قوانين وأعراف الحرب.[130] في قضية كوپرشكيتش وزملائه، المتعلقة بمذبحة أهميتشي، أدانت المحكمة الجنائية ليوغسلاڤيا السابقة عضوين محليين في مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي، وهم دراگو يوسيپوڤيتش وڤلاديمير شانتيتش، لارتكابهما جرائم ضد الإنسانية. حُكم عليهما بالسجن 12 و18 عاماً، على التوالي. برأت المحكمة أربعة من أعضاء مجلس الدفاع الكرواتي في القضية، زوران كوپرشكيتش، ميريان كوپرشكيتش، ڤلاتكو كوپشكيتش ودرگان پاپيتش. صدر حكم الاستئناف في القضية في أكتوبر 2001.[131]

في يوليو 2004، حُكم على تيهومير بلاشكيتش، قائد منطقة العمليات بوسط البوسنة التابعة لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي بالسجن 9 سنوات للمعاملة الغير إنسانية والقاسية للمعتقلين البشناق. حُكم عليه في البداية بالسجن 45 عام عام 2000، لكن في النقض حُكم بأن معظم الجرائم المرتكبة وقعت خارج منطقة مسئولية القيادة الخاصة به.[132] في ديسمبر 2004، داريو كورديتش، نائب رئيس البوسنة والهرسك السابق، حُكم عليه بالسجن 25 عاماً لارتكابه جرائم حرب تهدف للتطهير العرقي للبشناق في منطقة وسط البوسنة. ماريو تشركز، القائد السابق للواء ڤيتز، التابع لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي، حُكم عليه بالسجن ستة سنوات بتهمة السجن غير المشروع للمدنيين البشناق.[133]

إيڤيكا راجيتش، القائد السابق لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي في كيشلياك، اعترف بكونه مذنباً باشتراك في مذبحة ستوپني دو. حُكم عليه بالسجن 12 عاماً في مايو 2006.[134] ميروسلاڤ برالو، العضو السابق في وحدة يوكرز التابعة لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي، اعترف بكونه مذنباً في جميع الجرائم التي ارتكبت في وايد لاشڤا وحُكم عليه بالسجن 20 عاماً في أبريل 2007.[135]

في قضية توتا وشتلا، حُكم على القائد السابق لفصيلة المدانين، ملادن نالتيليتش توتا، بالسجن 20 عاماً، بينما حُكم على مرؤوسه ڤينكو مارتينوڤيتش بالسجن 18 عاماً. وجدت المحكمة كلاهما مذنبين في جريمة التطهير العرقي للمدنيين البشناق في منطقة موستار.[136]

في 28 نوفمبر 2017، حكمت المحكمة الجنائية ليوغسلاڤيا السابقة على يادرانكو پرليتش، رئيس وزراء البوسنة والهرسك السابق، بالسجن 25 عاماً، وعلى وزير الدفاع السابق برونو ستويتش وقائدين سابقين في الأركان الرئيس لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي، سلوبودان پراليياك وميليڤوي پتكوڤيتش، بالسجن 20 عاماً، وعلى ڤالتنين تشوريتش، الرئيس السابق للشرطة العسكرية التابعة لمجلس الدفاع الكرواتي، بالسجن 16 عاماً، وعلى برليسلاڤ پوشيتش، الذي كان رئيساً للسجون ومرافق الاعتقال، بالسجن 10 سنوات. تضمنت التهم جرائم ضد الإنسانية، انتهاكات قوانين أو أعراف الحرب، والانتهاكات الجسيمة لمعاهدات جنيڤ.[137] عند سماع حكم إدانته، قال سلوبودان پرالياك إنه لم يكن مجرم حرب وانتحر بشرب السم في قاعة المحكمة.[138]

أنور حاجيحسانوڤيتش، القائد السابق للفيلق الثالث بجيش جمهورية البوسنة والهرسك، وأمير كوبورا، القائد السابق للواء الإسلامي السابع، أدينا بإخفاقهما في اتخاذ التدابير اللازمة والمسئولة لمنع الجرائم المختلفة التي ارتكبتهما القوات تحت قيادتهما في وسط البوسنة. حُكم على أنور حاجيحسانوڤيتش بالسجن ثلاث سنوات ونصف، بينما حُكم على كوبورا بالسنة سنتين في 22 أبريل 2008.[139]

وجهت للقائد البوسني صفر خليلوڤيتش تهمة واحدة وهي انتهاك قوانين وأعراف الحرب على أساس المسؤولية الجنائية العليا للحوادث التي وقعت أثناء العملية نرتڤا 93 ولم تثبت إدانته.[140] الجنرال محمد عليگيتش، برأته المحكمة الجنائية ليوغسلاڤيا السابقة لكنه توفي عام 2003.[141]

التصالح

في يناير 1994، تأسس المجلس الوطني الكرواتي في سراييڤو، بخطة للتصالح والتعاون الكرواتي-البوشناقي .[142]

في أبريل 2010، قام الرئيس الكرواتي ايڤو يوسيپوڤتش بزيارة رسمية إلى البوسنة والهرسك أعرب أثنائها عن "أسفه عميق" لمساهمة كرواتيا في "معاناة الشعب وانقسامه" الذي لا يزال قائماً في البوسنة والهرسك. وقام يوسيپوڤتش برفقة قادة دينيين مسلمين ومسيحيين بدفع الدية للضحايا في أهميتشي وكريزانتشڤو سلو. انتقد يوسيپوڤتش بشدة على المستوى المحلي واتهمه يادرانكا كوسور، رئيس الوزراء الكرواتي وعضو الاتحاد الوطني الكرواتي، بانتهاك الدستور الكرواتي والإضرار بسمعة الدولة.[143]

في الثقافة العامة

يدور فيلم الرعب-العسكري الكرواتي الأحياء والأموات، يدور في سنوات الحرب.

الهوامش

- ^ CIA 1993, p. 28.

- ^ CIA 1993, p. 25.

- ^ Lukic & Lynch 1996, p. 202.

- ^ Burg & Shoup 1999, p. 107.

- ^ Shrader 2003, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Shrader 2003, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 30.

- ^ CIA 1993, p. 47.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 29.

- ^ Hadzihasanovic & Kubura Judgement Summary 2006, p. 3.

- ^ أ ب Farmer 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Schindler 2007, p. 126.

- ^ Schindler 2007, p. 167.

- ^ Schindler 2007, p. 99.

- ^ "Srebrenica – a 'safe' area". Netherlands Institute for War Documentation. 10 April 2002. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ "Ex-Yougoslavie: les phalanges" (in الفرنسية). 3 January 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21.

- ^ Karli, Sina (11 November 2006). "Šveđanin priznao krivnju za ratne zločine u BiH" [Swede confesses to war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina]. Nacional (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 30 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Shrader 2003, p. 69.

- ^ أ ب Shrader 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Marijan 2006, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 277.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 147.

- ^ أ ب ت CIA 2002, p. 159.

- ^ Marijan 2006, p. 392.

- ^ Prlic et al. judgement vol.2 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Prlic et al. judgement vol.2 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Marijan 2006, pp. 397–398.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Hoare 2010, p. 128.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 148.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 436.

- ^ Kordić & Čerkez Judgement 2001, p. 170.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUNHCHR - ^ Magaš & Žanić 2001, p. 366.

- ^ Christia 2012, pp. 175–6.

- ^ Malcolm 1995, p. 327.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 155.

- ^ أ ب CIA 2002, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Shrader 2003, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Tanner 2001, p. 288.

- ^ Hadzihasanovic & Kubura Judgement Summary 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Kordić & Čerkez Appeals Judgement Summary 2004, p. 7.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 191.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 22.

- ^ أ ب Christia 2012, p. 156.

- ^ أ ب Shrader 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 59.

- ^ أ ب Marijan 2004, p. 266.

- ^ Owen 1996, p. 146.

- ^ Associated Press 25 February 1996.

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 245.

- ^ أ ب CIA 2002b, pp. 433–434.

- ^ "Three Bosniak Soldiers Convicted of Trusina Massacre". justice-report.com. 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- ^ Naletilic & Martinovic Judgement 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. 618.

- ^ Prlic et al. judgement 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Christia 2012, pp. 161–162.

- ^ CIA 2002, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 160.

- ^ أ ب Christia 2012, pp. 157–158.

- ^ أ ب CIA 2002, p. 200.

- ^ Prlic et al. judgement vol.2 2013, p. 221.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 194.

- ^ أ ب Tanner 2001, p. 290.

- ^ Curic et al. Case Information 2015.

- ^ Christia 2012, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Dyker & Vejvoda 2014, p. 105.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 176.

- ^ Tabeau 2009, p. 234.

- ^ Tabeau 2009, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Bollens 2007, p. 171.

- ^ Tanner 27 July 1993.

- ^ Andreas 2011, p. 70.

- ^ أ ب CIA 2002b, p. 425.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 140.

- ^ CIA 2002, p. 199.

- ^ Toal & Dahlman 2011, p. 129.

- ^ أ ب Ramet 2010, p. 265.

- ^ Williams 15 January 1994.

- ^ أ ب ت Tanner 2001, p. 292.

- ^ Lewis 4 February 1994.

- ^ Christia 2012, p. 177.

- ^ أ ب Bethlehem & Weller 1997, p. liv.

- ^ Burg & Shoup 1999, pp. 293–294.

- ^ أ ب Mrduljaš 2009, p. 843.

- ^ Mrduljaš 2009, p. 837.

- ^ CIA 2002, pp. 242–243.

- ^ CIA 2002, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 452.

- ^ Bethlehem, Daniel L.; Weller, Marc (1997). The 'Yugoslav' Crisis in International Law. Cambridge International Documents Series. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. p. liiv. ISBN 978-0-521-46304-1.

- ^ Marijan 2004, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Ramet, Clewing & Lukić 2008, p. 121.

- ^ CIA 2002b, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Hoare March 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Sadkovich 2007, p. 207.

- ^ CIA 2002b, p. 293.

- ^ ICTY. "JUDGEMENT, Prosecutor vs. Kordic and Cerkez, p. 5, 39" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-01.

- ^ Sadkovich 2007, pp. 217, 219.

- ^ Sadkovich 2007, pp. 239–240.

- ^ أ ب Malcolm 1995, p. 318.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 434.

- ^ Bugajski 1995, p. 21.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 421.

- ^ Malcolm 1995, p. 319.

- ^ Almond 2003, p. 197.

- ^ Shrader 2003, p. XVII.

- ^ Marijan 2004, p. 286.

- ^ Ramet, Clewing & Lukić 2008, p. 120.

- ^ "Kordić & Čerkez (IT-95-14/2) | Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2001. p. 38. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ "WITNESS NAME: Paddy Ashdown (extract from transcript, pages 2331 – 2356)". CASE IT-02-54 PROSECUTOR vs. SLOBODAN MILOŠEVIĆ. ICTY. 14 March 2002.

- ^ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia Prlić et al. CIS, p. 6.

- ^ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia 29 May 2013.

- ^ Prlic et al. judgement vol.6 2013, pp. 212, 374, 377.

- ^ http://icr.icty.org/LegalRef/CMSDocStore/Public/English/Decision/NotIndexable/IT-04-74-A/MRA24991R0000483864.pdf Archived 2021-02-24 at the Wayback Machine[bare URL PDF]

- ^ أ ب "Prlić et al. (IT-04-74) | International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Appeals Chamber, Judgement - Volume II. p. 260-282". www.icty.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Bullough 7 نوفمبر 2007.

- ^ Walasek 2015, p. 24.

- ^ أ ب Walasek 2015, p. 127.

- ^ Riedlmayer 2002, p. 100.

- ^ Sells 2003, pp. 220–1.

- ^ Islam and Bosnia: Conflict Resolution and Foreign Policy in Multi-Ethnic States, Maya Shatzmiller, page 100, 2002

- ^ Ilija Živković: Raspeta crkva u Bosni i Hercegovini: uništavanje katoličkih sakralnih objekata u Bosni i Hercegovini (1991.-1996.), 1997, page 357

- ^ أ ب Schindler 2007, p. 264.

- ^ أ ب Davis 2005, p. 116.

- ^ Kohlmann 2004, pp. 197–199.

- ^ Kohlmann 2004, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Tatalović & Jakešević 2008, pp. 140–1.

- ^ "Aleksovski case: The Appeals Chamber increases his Sentence to seven years imprisonment". ICTY. 24 March 2000.

- ^ "Appeals Chamber unanimously dismisses Furundzija and affirms Convictions and Sentence". ICTY. 21 July 2000.

- ^ "Appeals Judgement rendered in the Kupreskic & others case". ICTY. 23 October 2001.

- ^ "Appeals Chamber Judgement in the case the Prosecutor v. Tihomir Blaskic". ICTY. 29 July 2004.

- ^ "Appeals Chamber Judgement in the Case the Prosecutor v. Dario Kordic and Mario Cerkez". ICTY. 17 December 2004.

- ^ "Ivica Rajic Sentenced to 12 Years' Imprisonment". ICTY. 8 May 2006.

- ^ "Appeals Chamber dismisses Miroslav Bralo's appeal affirms sentence of 20 years' imprisonment". ICTY. 2 April 2007.

- ^ "Appeals Chamber Confirms Sentences Against Mladen Naletilic and Vinko Martinovic". ICTY. 3 May 2006.

- ^ "The ICTY renders its final judgement in the Prlić et al. appeal case". ICTY. 29 November 2017.

- ^ Stephanie van den Berg; Bart H. Meijer (29 November 2017). "Bosnian Croat war crimes convict dies after taking 'poison' in U.N. court". Reuters. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Hadžihasanović & Kubura Appeals Only Partially Granted". ICTY. 22 April 2008.

- ^ Halilovic judgement 2013.

- ^ Del Ponte, Carla (2002-01-11), The Prosecutor of the Tribunal Against Enver Hadžihasanović, Mehmed Alagic, Amir Kubura : Amended Indictment, Archived from the original on 2005-11-13, https://web.archive.org/web/20051113224441/http://www.un.org/icty/indictment/english/had-ai020111e.htm, retrieved on 2008-11-30

- ^ Goldstein 1999, p. 248.

- ^ Denti 2013, pp. 111–2.

المصادر

كتب ودوريات

- Almond, Mark (1994). Europe's backyard war: the war in the Balkans. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-00003-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Almond, Mark (December 2003). "Expert Testimony". Review of Contemporary History. Oriel College, University of Oxford: Croatian Institute of History. 36 (1): 177–209.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Andreas, Peter (2011). Blue Helmets and Black Markets. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801457043.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bellamy, Alex J. (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6502-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Benthall, Jonathan; Bellion-Jourdan, Jerome (2003). Charitable Crescent: Politics of Aid in the Muslim World. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857711250.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bethlehem, Daniel; Weller, Marc (1997). The Yugoslav Crisis in International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521463041.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bollens, Scott A. (2007). Cities, Nationalism and Democratization. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-11183-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bugajski, Janusz (1995). Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations and Parties. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-283-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (1999). The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3189-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Calic, Marie–Janine (2012). "Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes, 1991–1995". In Ingrao, Charles; Emmert, Thomas A. (eds.). Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative (2nd ed.). West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 114–153. ISBN 978-1-55753-617-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995, Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. ISBN 978-0-16-066472-4.

- Central Intelligence Agency (1993). Combatant Forces in the Former Yugoslavia (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency.

- Christia, Fotini (2012). Alliance Formation in Civil Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13985-175-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cigar, Norman (1995). Genocide in Bosnia: The Policy of "Ethnic Cleansing". College Station: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-004-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coakley, John (2013). Pathways from Ethnic Conflict: Institutional Redesign in Divided Societies. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317988472.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, John (2005). The Global War on Terrorism: Assessing the American Response. Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 9781594542282.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Denti, Davide (2013). "Ethnic Cleansing and War Crimes, 1991–1995". In Cuypers, Daniël; Janssen, Daniel; Haers, Jacques; Segaert, Barbara (eds.). Public Apology between Ritual and Regret: Symbolic Excuses on False Pretenses or True Reconciliation out of Sincere Regret?. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 103–122. ISBN 9789401209533.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dyker, David A.; Vejvoda, Ivan (2014). Yugoslavia and After: A Study in Fragmentation, Despair and Rebirth. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 9781317891352.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farmer, Brian R. (2010). Radical Islam in the West: Ideology and Challenge. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6210-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gallagher, Tom (2003). The Balkans After the Cold War: From Tyranny to Tragedy. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781134472406.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glenny, Misha (1996). The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-025771-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-525-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gow, James; Paterson, Richard; Preston, Alison R. (1996). Bosnia by Television. London: British Film Institute.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grandits, Hannes (2016). "The Power of 'Armchair Politicians': Ethnic Loyalty and Political Factionalism among Herzegovinian Croats". In Bougarel, Xavier; Helms, Elissa; Duijzings, Gerlachlus (eds.). The New Bosnian Mosaic: Identities, Memories and Moral Claims in a Post-War Society. London: Routledge. pp. 101–122. ISBN 9781317023081.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoare, Marko Attila (March 1997). "The Croatian Project to Partition Bosnia-Hercegovina, 1990–1994". East European Quarterly. 31 (1): 121–138.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2004). How Bosnia Armed. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-86356-367-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hockenos, Paul (2003). Homeland Calling: Exile Patriotism and the Balkan Wars. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4158-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Klemenčić, Mladen; Pratt, Martin; Schofield, Clive H. (1994). Territorial Proposals for the Settlement of the War in Bosnia-Hercegovina. IBRU. ISBN 9781897643150.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kohlmann, Evan F. (2004). Al-Qaida's Jihad in Europe: The Afghan-Bosnian Network. Berg. ISBN 1-85973-807-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Krišto, Jure (April 2011). "Deconstructing a myth: Franjo Tuđman and Bosnia and Herzegovina". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 6 (1): 37–66.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gosztonyi, Kristóf (2003). "Non-Existent States with Strange Institutions". In Koehler, Jan; Zürcher, Christoph (eds.). Potentials of Disorder: Explaining Conflict and Stability in the Caucasus and in the Former Yugoslavia. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 46–61. ISBN 9780719062414.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kurspahić, Kemal (2003). Prime Time Crime: Balkan Media in War and Peace. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace. ISBN 9781929223398.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lawson, Edward H.; Bertucci, Mary Lou (1996). Encyclopedia of Human Rights. Washington D.C.: Taylor & Francis.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lukic, Reneo; Lynch, Allen (1996). Europe from the Balkans to the Urals: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-829200-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacDonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centered Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6467-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Magaš, Branka; Žanić, Ivo (2001). The War in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina 1991–1995. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-8201-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malcolm, Noel (1995). Povijest Bosne: kratki pregled [Bosnia: A Short History]. Erasmus Gilda. ISBN 9789536045037.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marijan, Davor (December 2006). "Sukob HVO-a i ABIH u Prozoru, u listopadu 1992" [Clash of the HVO and the ARBiH in Prozor, in October 1992]. Journal of Contemporary History (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 38 (2): 379–402. ISSN 0590-9597.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Marijan, Davor (2004). "Expert Opinion: On the War Connections of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (1991 – 1995)". Journal of Contemporary History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 36: 249–289.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moore, Adam (2013). Peacebuilding in Practice: Local Experience in Two Bosnian Towns. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-5199-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mrduljaš, Saša (2009). "Hrvatska politika unutar Bosne i Hercegovine u kontekstu deklarativnog i realnoga opsega Hrvatska zajednice / republike Herceg-Bosne" [Croatian policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the context of declarative and real extent of the Croatian Community / Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia]. Journal for General Social Issues (in Croatian). Zagreb: Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar. 18: 249–289.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Mulaj, Kledja (2008). Politics of Ethnic Cleansing: Nation-State Building and Provision of Insecurity in Twentieth-Century Balkans. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780739146675.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nizich, Ivana (1992). War Crimes in Bosnia-Hercegovina. Vol. 1. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-083-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Owen, David (1996). Balkan Odyssey. London: Indigo. ISBN 9780575400290.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Perica, Vjekoslav (2002). Balkan Idols: Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19517-429-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramet, Sabrina P.; Clewing, Konrad; Lukić, Reneo, eds. (2008). Croatia since Independence: War, Politics, Society, Foreign Relations. Munich: Oldenbourg. ISBN 978-3-48658-043-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ramet, Sabrina P. (2010). "Politics in Croatia since 1990". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 258–285. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Riedlmayer, András (2002). "From the Ashes: The Past and Future of Bosnia's Cultural Heritage". In Shatzmiller, Maya (ed.). Islam and Bosnia: Conflict Resolution and Foreign Policy in Multi-Ethnic States. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 98–135. ISBN 9780773523463.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sadkovich, James J. (January 2007). "Franjo Tuđman and the Muslim-Croat War of 1993". Review of Croatian History. Zagreb, Croatia: Croatian Institute of History. 2 (1): 204–245. ISSN 1845-4380.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schindler, John R. (2007). Unholy Terror: Bosnia, Al-Qa'ida, and the Rise of Global Jihad. New York City: Zenith Press. ISBN 9780760330036.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sells, Michael Anthony (1998). The Bridge Betrayed: Religion and Genocide in Bosnia. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92209-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sells, Michael A. (2003). "Sacral Ruins in Bosnia-Gerzegovina: Mapping Ethnoreligious Nationalism". In Prentiss, Craig R. (ed.). Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity: An Introduction. New York: New York University Press. pp. 211–234. ISBN 9780814767009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Takeyh, Ray; Gvosdev, Nikolas K. (2004). The Receding Shadow of the Prophet: The Rise and Fall of Radical Political Islam. London: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275976293.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shrader, Charles R. (2003). The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia: A Military History, 1992–1994. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-261-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tatalović, Siniša; Jakešević, Ružica (2008). "Terrorism in the Western Balkans – The Croatian Experience and Position". In Prezelj, Iztok (ed.). The Fight Against Terrorism and Crisis Management in the Western Balkans. Ljubjana: IOS Press. pp. 132–146. ISBN 9781586038236.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: A Nation Forged in War. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09125-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toal, Gerard; Dahlman, Carl T. (2011). Bosnia Remade: Ethnic Cleansing and Its Reversal. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973036-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trifunovska, Snežana (1994). Yugoslavia Through Documents: From its Creation to its Dissolution. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7923-2670-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Udovički, Jasminka; Štitkovac, Ejub (2000). "Bosnia and Hercegovina: The Second War". In Udovički, Jasminka; Ridgeway, James (eds.). Burn This House: The Making and Unmaking of Yugoslavia. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 175–216. ISBN 978-0-8223-2590-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walasek, Helen (2015). Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage. Dorchester: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9781409437048.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zürcher, Christoph (2003). Potentials of Disorder: Explaining Conflict and Stability in the Caucasus and in the Former Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6241-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

مقالات جديدة

- Bullough, Oliver (7 November 2007). "Transcripts Suggest Croatia Conspired to Break Up Bosnia". Institute for War & Peace Reporting.

- Burns, John F. (6 July 1992). "Croats Claim Their Own Slice of Bosnia". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (21 July 1992). "U.N. Resumes Relief Flights to Sarajevo". New York Times.

- Burns, John F. (26 July 1992). "Croatian Pact Holds Risks for Bosnians". New York Times.

- "West Rejects Revision Of Dayton Accords". Chicago Tribune. 2 June 1999.

- Hedges, Chris (16 November 1997). "At Home and Under Duress With Bosnian Croats". New York Times.

- Hedl, Dragutin (5 September 2000). "Bosnian Trade Off". Institute for War & Peace Reporting.

- Lashmar, Paul; Bruce, Cabell; Cookson, John (1 November 2000). "Secret recordings link dead dictator to Bosnia crimes". The Independent.

- Lušić, Bisera (3 November 2000). "Britanci su od Mesića dobili samo intervju, ne i transkripte" [The British only got an interview from Mesić, not the transcripts]. Slobodna Dalmacija.

- Myers, Linnet (6 May 1993). "Bosnian Serbs Spurn Un Pact, Set Referendum". Chicago Tribune.

- O'Connor, Mike (16 December 1995). "5 Islamic Soldiers Die in Shootout With Croats". New York Times.

- Perlez, Jane (15 August 1996). "Muslim and Croatian Leaders Approve Federation for Bosnia". New York Times.

- Pringle, Peter (7 March 1993). "Progress on Vance-Owen map for Bosnia". The Independent.

- Kurt, Schork (19 October 1993). "Winter of trench warfare looms: Muslims and Croats deadlocked in valley". The Independent.

- Sudetic, Chuck (7 September 1992). "Croatians Insist Muslim Fighters Leave Sarajevo Buffer Area". New York Times.

- Sudetic, Chuck (8 September 1992). "Croatian Militia Denies Issuing a Broad Challenge to Bosnia". New York Times.

- Tanner, Marcus (27 July 1993). "Bosnia: New commander vows to return fire". The Independent.

- Williams, Carol J. (9 May 1992). "Serbs, Croats Met Secretly to Split Bosnia". Los Angeles Times.

- Williams, Carol J. (15 January 1994). "Croatia Risks Cutting Its Own Throat". Los Angeles Times.

مراجع دولية، حكومية ومن منظمات غير حكومية

- Nizich, Ivana; Markić, Željka (1995). Civil and Political Rights in Croatia. Helsinki: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 9781564321480.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Prlić et al. – Case Information Sheet" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. IT-04-74.

- "Prosecutor v. Tihomir Blaskić Judgement Summary" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 3 March 2000.

- "Prosecutor v. Kordić and Čerkez Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 26 February 2001.

- "Prosecutor v. Kordić & Čerkez Appeals Judgement Summary" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 17 December 2004.

- "Prosecutor v. Rasim Delić Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 September 2008.

- "Prosecutor v. Rasim Delić Judgement Summary" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 September 2008.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 1 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 2 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 4 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić, Berislav Pušić – Judgement – Volume 6 of 6" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- "Prosecutor v. Hadžihasanović & Kubura Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 15 March 2006.

- "Prosecutor v. Hadžihasanović & Kubura Judgement Summary" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. March 2006.

- "Prosecutor v. Naletilić & Martinović Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 31 March 2003.

- "Prosecutor v. Nisvet Gasal, Musajb Kukavica and Senad Dautović". Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2011.

- "Prosecutor v. Ćurić Enes, Demirović Ibrahim, Kreso Samir, Čopelja Habib and Kaminić Mehmed". Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- "Prosecutor v. Sefer Halilović – Appeals Chamber Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 16 Nov 2005.

- "Prosecutor v. Sefer Halilović – Appeals Chamber Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 16 Oct 2007.

- "Six Senior Herceg-Bosna Officials Convicted". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 29 May 2013.

- Reshaping International Priorities In Bosnia And Herzegovina – Part I – Bosnian Power Structures. European Stability Initiative. 14 October 1999. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.esiweb.org/pdf/esi_document_id_4.pdf. - Tabeau, Ewa (2009). Conflict in Numbers: Casualties of the 1990s Wars in the Former Yugoslavia (1991–1999) (PDF). Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- All articles with bare URLs for citations

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from March 2022

- Articles with PDF format bare URLs for citations

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2012

- مقالات ذات عبارات محل شك

- نزاعات 1992

- نزاعات 1993

- نزاعات 1994

- 1992 في البوسنة والهرسك

- 1993 في البوسنة والهرسك

- 1994 في البوسنة والهرسك

- حرب البوسنة

- حروب أهلية لدول وشعوب أوروپا

- حروب كرواتيا

- العلاقات البوسنية الكرواتية

- حروب البلقان

- تاريخ اتحاد البوسنة والهرسك

- الوطنية الكرواتية في البوسنة والهرسك

- العنف الإسلامي المسيحي