تاريخ المجر قبل الفتح الهنغاري

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| تاريخ المجر |

|---|

|

| التاريخ القديم |

| قبل التاريخ |

| العصور الوسطى |

| المجر في العصور الوسطى (896–1526) |

| الحروب العثمانية المجرية |

| المجر أوائل العصر الحديث |

| المجر الملكية |

| إمارة ترانسلڤانيا |

| تاريخ المجر 1700–1918 |

| القرن 19 |

| ثورة 1848–49 |

| القرن 20 |

| المجر في الحرب العالمية الأولى |

| فترة بين الحربين (1918–41) |

| المجر في الحرب العالمية الثانية |

| الجمهورية الشعبية 1949–89 |

| ثورة 1956 |

| 1989 – الآن |

| موضوعات في التاريخ المجري |

| التاريخ العسكري |

| تاريخ سيكي |

| تاريخ اليهود في المجر |

| التاريخ الموسيقي |

| تاريخ ترانسلڤانيا |

| The Csangos |

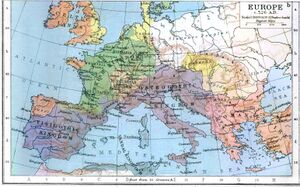

The history of Hungary before the Hungarian conquest spans the time period before the Hungarian conquest in the 9th century of the territories that would become the Principality of Hungary and the Kingdom of Hungary.

The first known traces belong to the Homo heidelbergensis, with scarce or nonexistent evidence[1] of human presence until the Neanderthals around 100,000 years ago. Anatomically modern humans arrived at the Carpathian Basin before 30,000 BC and belonged to the Aurignacian group.[2] The rest of the Stone Age is marked by minimal or not-yet-processed archeological evidence, with the exception of the Linear Pottery culture—the "garden type civilization"[3] that introduced agriculture to the Carpathian Basin.

During the Copper and Bronze Ages, three significant groups were the Baden, the Makó and the Ottomány (to not be confused with Ottoman Turks) cultures. The major improvement was obviously metalworking, but the Baden culture also brought about cremation and even long-distance trade with remote areas such as the Baltic or Iran. Turbulent changes during the late Bronze Age gave an end to the native, relatively advanced[4][مرجع دائرة مفرغة] civilization, and the beginning of the Iron Age saw mass immigration of Indo-European nomads believed to be of ancient Iranian ancestry. However, as the time went on, the Carpathian Basin attracted immigration from all directions: the Hallstatt Celts from the west were the first and most influential at around 750 BC, the mysterious Sigynnae around 500 BC, the Pannonians—an Illyrian tribe gave the future Roman province its name, while the very east became occupied by other Thracian, Iranian, and later Celtic tribes. Before 100 BC, most of the area was occupied by various Celtic or celticized people, such as the successor of the Halstatt culture, the Taurisci, the Boii, and the Pannonians.

The Roman era began with several attacks between 156 and 70 BC, but their gradual conquest was interrupted by the Dacian king Burebista, whose kingdom stretched as far as today's Slovakia at its greatest extent. However, the period of Dacian dominance did not last long, and by 9 BC the Romans had subjugated the entire area and made it into the Pannonia subprovince of province Illyricum and eventually Pannonia province. Under Roman rule, many contemporary cities such as Buda, Győr and Sopron were founded and the population romanized, and culture as a whole flourished. Roman emperors sometimes tolerated other tribes settling in the territory, such as the Iazyges or Vandals. Christianity spread during the 4th century, when it became the state religion.

In the first years of the Age of Migration, the Carpathian Basin was settled by the Huns who by 430 had established a vast, if short-lived, dominion in Europe centered in the basin. Numerous Germanic tribes lived alongside them such as the Goths, Marcomanni, Quadi or Gepidi, the last of which stayed the longest and whose peoples incorporated into the Hunnic Empire. The next wave of migration during the 6th century saw other Germanic tribes, the Lombards and Heruli overpower the Gepidi, only to be ousted by another major nomadic tribe, the Avars. Like the Huns, the Avars established an empire there and posed a significant threat to their neighbours but were eventually defeated by both neighbouring states and internal strife (around 800). However, Avar population remained quite steady until the Hungarian conquest. The territory became divided between East Francia and First Bulgarian Empire with the northeastern part under Moravian Slavic Principality of Nitra. This state lasted until the arrival of the Magyar tribes in the late 9th century.

قبل التاريخ

العصر الحجري

Vértesszőlős, Homo heidelbergensis

The oldest archaeological site which yielded evidence of human presence—human bones, pebble tools and kitchen refuse—in the Carpathian Basin was excavated at Vértesszőlős in Transdanubia in the 1960s.[5][6] The Middle Pleistocene site was situated in calcareous tuff basins with a diameter of 3–6 meters (9.8–19.7 ft) that the nearby warm springs had formed.[7][8] The site at Vértesszőlős was occupied five times[7] between about 500,000 and 250,000 years ago.[8]The occipital bone of an adult male Homo heidelbergensis, who is now known as "Samu", and a child's milk tooth were found.[1][9] Tools of quartzite and silex pebbles collected at the nearby river were also found,[10] as well as a fireplace with hearths made from crushed animal bones, with remains of wild horses, aurochs, bisons, red deer, deer, wolves, bears, and saber-toothed cats.[10][9][11]

فجوة في السجلات

There is a gap in the archaeological record, with no evidence of human presence between about 250,000 to 100,000 years ago.[1]

أواسط العصر الحجري القديم والنياندرتال

The earliest Middle Palaeolithic sites are dated to the transitory period between the Riss and Würm glacial periods around 100,000 years ago.[1] Remains of skulls show that Neanderthals inhabited northeastern Transdanubia and the Bükk Mountains during this period.[8][1] The Neanderthals who lived in the region of Érd between around 100,000 and 40,000 BC used quartzite pebbles.[12] They led hunting expeditions as far as the Gerecse Hills for cave bears, wild horses, woolly rhinoceros and other animals.[12] A Neanderthal community settled near the hot-water springs at Tata around 50,000 BC.[12] They hunted mammoth calves, brown bear, wild horses and reed deer.[12] A flat oval object made from mammoth tooth lamella, similar to the Indigenous Australians' ritual tjurunga, was found at the site.[12] A third group of Neanderthals settled in the caves of the Pilis, Vértes and Gerecse Hills.[13] They regularly visited the Bükk Mountains and the White Carpathians to collect raw material for their tools.[13] Ibex was the main prey of the Neanderthals of the Middle Palaeolothic sites in the Bükk Mountains.[13] In addition to local stone, they used raw material from the White Carpathians and the region of the river Prut.[13] Archaeological research suggest that the Neanderthals disappeared from the northern regions of the Carpathian Basin around 40,000 years ago.[14]

Istállóskő Cave, Aurignacian group

Latest research shows that the first communities of anatomically modern humans came to the Carpathian Basin between 33,000 and 28,000 BC.[14] Consequently, the cohabitation of the Neanderthals and modern humans in the territory, which was assumed by earlier scholarship, cannot be proved.[14] The Aurignacian group of modern humans who settled in the Istállóskő Cave primarily used tools made of bones and used the cave as a seasonal camping site during their hunts for chamois, red deer, reindeer and other local animals.[2] Their tools made of stone suggest that they came to the Bükk Mountains from the northern Carpathians and the region of the Prut.[2]

Szelete culture

According to a scholarly view, a local archaeological culture—the "Szeleta culture"—can be distinguished, which represents a transition between the Middle and Upper Palaeolithic and was featured by leaf-shaped spearheads from around 32,000 BC.[8][2][15] However, the existence of a distinct archaeological culture is not unanimously accepted by specialists, because most prehistoric tools from the eponymous Szeleta Cave (in the eastern side of the Bükk) are similar to those found in the Upper Palaeolithic sites of Central Europe.[15]

Gravettian hunters

Attracted by the rich fauna of the lowlands in the centre of the Carpathian Basin, groups of "Gravettian" hunters penetrated into the territory from the west about 27,000 years ago.[2] The central grasslands were not covered by ice even at the maximum of the last glaciation (around 20,000 years ago).[2][16] The new arrivals settled on hilltops along the rivers Hornád and Bodrog.[17] They primarily hunted mammoth and elk and used stone blades to work skin, bone, antler and wood.[17] Artistic finds are rare; for instance, a disc with serrated edges, which was made of polished limestone, was found at Bodrogkeresztúr.[17] A second wave of "Gravettians" arrived during the warmer period that began about 20,000 years ago.[18] They primarily made their tools from pebbles, similar to Lower Palaeolithic communities, but no continuity between the two groups can be detected.[18] The remains of semi-sunken huts were excavated at a site on a hilltop near Sárvár where reindeer bones were also found.[18] The site also yielded a perforated (but not decorated) reindeer antler.[18] In addition to permanent settlements, the Gravettian hunters' temporary camps were unearthed in the plains of the Jászság and around Szeged.[18] About 15,000 years ago, new hunters came to the territory; their best-known settlements were situated in northeastern Transdanubia.[18] A pendant made of wolf tooth, a pair of red deer teeth and similar finds suggest that these hunters wore ornaments.[18]

العصر الحجري الوسيط

Mesolithic sites are rare but start to appear after systematic surveys, especially in the Jászság area.

Tardenoisian culture, 9000–4000 BC

The Tardenoisian (or Beuronian) is an archaeological culture of the Mesolithic/Epipaleolithic period from northern France and Belgium. Similar cultures are known further east in Central Europe, parts of Britain and west across Spain, extending possibly to the nowadays North-Western Hungary.

Starčevo culturem 6200–4500 BC

The Starčevo culture is an archaeological culture of Southeastern Europe, dating to the Neolithic period between c. 6200 and 4500 BCE. It originates in the spread of the Neolithic package of peoples and technological innovations including farming and ceramics from Anatolia to the area of Sesklo. The Starčevo culture marks its spread to the inland Balkan peninsula as the Cardial ware culture did along the Adriatic coastline. It forms part of the wider Starčevo–Körös–Criş culture which gave rise to the central European Linear Pottery culture c. 700 years after the initial spread of Neolithic farmers towards the northern Balkans.

Criş-Körös culture, ~6200 BC

Neolithic settlement begins with the Criş-Körös culture, carbon-dated to around 6200 BC.

Linear Pottery, 5500–4500 BC

In the Middle Neolithic, the Western Linear Pottery culture in Transdanubia and the Satu-Mare (Szatmar) and Eastern Linear pottery (called "Alföld Linear Pottery" in Hungary) in the east, developed into Želiezovce (Slovakia) and Szakálhát and Bükk, respectively.

Vinča culture ~5400–4500 BC

Farming technology first introduced to the region during the First Temperate Neolithic was developed further by the Vinča culture. It was noted for dark-burnished pottery, and fuelling a population boom and producing some of the largest settlements in prehistoric Europe.

Tisza culture, ~5400–4500 BC

The Tisza culture is a Neolithic archaeological culture of the Alföld plain in modern-day Hungary, Western Romania, Eastern Slovakia, and Ukrainian Zakarpattia Oblast in Central Europe. The culture is dated to between 5400 BCE and 4500/4400 BCE.

Tiszapolgár culture 4500–4000 BC

The Late Neolithic Tisza culture was followed by the Eneolithic Tiszapolgár and Bodrogkeresztúr cultures. These cultures were part of the broader cultural complex known as Old Europe or the Danube civilization.

Bodrogkeresztúr culture 4000 to 3600 BC.

The Bodrogkeresztúr culture is best known for its seventy cemeteries. Which show clear genetic links with the preceding Tiszapolgár culture. Bodrogkeresztúr cemetieres make clear distinctions between males and females.

Sopot culture, ~5000 BC

The Sopot culture is a neolithic archaeological culture that was first identified in eastern Slavonia in modern-day Croatia, and was since also found in several sites in Hungary.

Baden Culture, 3600–2800 BC

The Baden culture was a Copper Age (Chalcolithic) archaeological culture found in Central Europe. In Hungarian and Slovakian sites, cremated human remains were often placed in anthropomorphic urns, whereas in Nitriansky Hrádok, a mass grave has been found. The only known cemetery with individual graves was found in an early Baden ("Boleráz phase") site is Pilismarót, in Komárom-Esztergom County, which also contained a few examples of goods possibly exported from the Stroke-ornamented ware culture (centred in what is now Poland). The Baden culture is claimed by some scholars to have been an early example of an Indo-European culture in Central Europe.

Tisza culture ceramic altar, 5300-5200 BC.[19]

Anthropomorphic vessel, Linear Pottery culture, c. 5400-4500 BC

Neolithic longhouse, Linear Pottery culture, c. 5500-4500 BC

Gold idol, Bodrogkeresztúr culture, c. 4000-3600 BC

Copper ornaments, Tiszapolgar culture, c. 4000 BC

Ceramic vessel, Baden culture, c. 4th millennium BC

Modern sculpture of a Baden culture wagon model, c. 3300 BC.[20]

Bronze Age

Makó (a town in modern Csongrád County) lends its name to a 3rd millennium BCE material culture (also known as the Makó-Caka or Kosihy-Caka culture) and other archaeological finds from the Copper/Bronze Ages. There are more than 180 registered archaeological sites around Makó, the most important of which are at Kiszombor. The Makó culture is often regarded as a subset or offshoot of the broader Vučedol culture, centred on Vukovar). While there is no consensus on the cultural affiliations of the Makó sites, kurgans, buckles, jewelry and equestrian equipment found near Makó may suggest links to nomads migrating from the Eurasian steppe. In later phases, these sites contain very large numbers of objects associated with the Sarmatians.

The Ottomány culture (also known as the Otomani-Füzesabony culture) was a Bronze Age culture (circa 2100–1400 BC) stretching from eastern Hungary and western Romania to southeast Poland and western Ukraine. Amber exported on prehistoric trade routes from the Baltic is often found at Ottomány sites and the people of this culture appear to have held a central part of the so-called "Amber Road", which connected the powerful and rising ancient Mediterranean states to the south-eastern Baltic region. The Ottomány culture was succeeded by the Tumulus culture and Urnfield culture.

Bronze dagger, 2000-1800 BC[21]

Amber and gold hoard, Hatvan culture, 18th century BC

Hajdúsámson-type sword, Ottomány culture, 1700-1600 BC.[22][23]

Gold armband, Vatya culture, c. 1500 BC

Gold jewellery, Encrusted Pottery culture, c. 1500 BC

Gold jewellery, Tumulus culture, 15th century BC

Middle Bronze Age burials, museum diorama

Bronze diadem, Urnfield culture, c. 1200 BC

Bronze situla, Urnfield culture, c. 1000 BC.[24]

Bronze oil lamp, Urnfield culture[25]

Százhalombatta-Földvár fortified settlement site

Iron Age

In the Carpathian Basin, the Iron Age commenced around 800 BC, when a new population moved into the territory and took possession of the former population's centers fortified by earthworks.[26][27] The new population may have consisted of ancient Iranian tribes that had seceded from the federation of the tribes living under the suzerainty of the Cimmerians.[26][27] They were equestrian nomads and formed the people of the Mezőcsát culture who used tools and weapons made of iron. They extended their rule over what are now the Great Hungarian Plain and the eastern parts of Transdanubia.[27]

Around 750 BC, people of the Hallstatt culture gradually occupied the western parts of Transdanubia, but the earlier population of the territory also survived and thus the two archaeological cultures existed together for centuries.[26] The people of the Hallstatt culture took over the former population's fortifications (e.g., in Velem, Celldömölk, Tihany) but they also built new ones enclosed with earthworks (e.g., in Sopron).[26][27] The nobility were buried in chamber tombs covered by earth.[26] Some of their settlements situated along the Amber Road developed into commercial centers.[26][27]

The classic Scythian culture spread across the Great Hungarian Plain between the 7th–6th century BC.[28]

Between 550 and 500 BC, new people settled along the river Tisza and in Transylvania.[26][27] Their immigration may have been connected either to the military campaigns of king Darius I of Persia (522 BC – 486 BC) on the Balkan Peninsula or to the struggles between the Cimmerians and the Scythians.[26][27] Those people, who settled down in Transylvania and in the Banat, may be identified with the Agathyrsi (probably an ancient Thracian tribe whose presence on the territory was recorded by Herodotus); while those who lived in what is now the Great Hungarian Plain may be identified with the Sigynnae.[26] The new population introduced the use of the potter's wheel in the Carpathian Basin and they maintained close commercial contacts with the neighboring peoples.[26]

The Pannonians (an Illyrian tribe) may have moved to the southern territories of Transdanubia in the course of the 5th century BC.[26]

In the 4th century BC, Celtic tribes immigrated to the territories around the river Rába and defeated the Illyrian people who had been living there, but the Illyrians managed to assimilate the Celts, who adopted their language.[27] In the 290s and 280s BC, the Celtic people who were migrating towards the Balkan Peninsula passed through Transdanubia but some of the tribes settled on the territory.[26] Following 279 BC, the Scordisci (a Celtic tribe), who had been defeated at Delphi, settled at the confluence of the rivers Sava and Danube and they extended their rule over the southern parts of Transdanubia.[26] Around that time, the northern parts of Transdanubia were ruled by the Taurisci (also a Celtic tribe) and by 230 BC, Celtic people (the people of the La Tène culture) had occupied gradually the whole territory of the Great Hungarian Plain.[26] Between 150 and 100 BC, a new Celtic tribe, the Boii moved to the Carpathian Basin and they occupied the northern and northeastern parts of the territory (mainly the territory of present Slovakia).[26]

Celtic iron artefacts, La Tène culture

Remains of a burial mound, 500 BC

Roman era

The Romans commenced their military raids in the Carpathian Basin in 156 BC when they attacked the Scordisci living in the Transdanubian region.[26][27] In 119 BC, they marched against Siscia (today Sisak in Croatia) and strengthened their rule over the future Illyricum province south of the Carpathian Basin.[26] In 88 BC, the Romans defeated the Scordisci whose rule was driven back to the eastern parts of Syrmia, while the Pannonians moved to the northern parts of Transdanubia.[26][27] When King Mithridates VI of Pontus made plans to attack the Romans by way of the Balkan Peninsula, he referred to the Pannonic tribes, and not to the Scordisci, as masters of the region on his path; it appears, therefore, that around 70–60 BC, the Pannonic tribes were no longer subjugated.[26]

Around 50 BC, the mainly Celtic tribes living on the territory were confronted by Burebista, king of the Dacians (82–44 BC), who began suddenly to expand his domain centered in Transylvania.[29] The sources do not indicate clearly whether Burebista was the original unifier of the Dacian tribes, or whether his efforts at unification built upon the work of his predecessors.[29] Burebista subjugated the Taurisci and the Anarti; in the process, he confronted the Celtic tribal alliance led by the Boii.[27][29] Burebista's victory over the Celts led not only to the breakup of their tribal alliance, but also to the establishment of Dacian settlements in the southern parts of today's Slovakia.[29] Burebista, however, fell victim to his political enemies, and his domain was divided into four parts.[29]

The period between 15 BC and 9 AD was characterized by the continuous uprisings of the Pannonians against the emerging power of the Roman Empire. The Romans, however, could strengthen their supremacy over the rebellious tribes and they organised the occupied territory into a new province.[26]

Pannonia province

The Roman Empire subdued the Pannonians, Dacians, Celts and other peoples in this territory. The territory west of the Danube was conquered by the Roman Empire between 35 and 9 BC, and became a province of the Roman Empire under the name of Pannonia. The easternmost parts of present-day Hungary were later (106 AD) organized as the Roman province of Dacia (lasting until 271). The territory between the Danube and the Tisza was inhabited by the Sarmatian Iazyges between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, or even earlier (earliest remains have been dated to 80 BC). Roman Emperor Trajan officially allowed the Iazyges to settle there as confederates. The remaining territory was in Thracian (Dacian) hands. In addition, the Vandals settled on the upper Tisza in the second half of the 2nd century AD.

Like in the other provinces, in Pannonia, the material culture of the native population showed little sign of Romanization in the first 160 years of Roman rule.[30]

The four centuries of Roman rule created an advanced and flourishing civilization. Many of the important cities of today's Hungary were founded during this period, such as Aquincum (Budapest), Sopianae (Pécs), Arrabona (Győr), Solva (Esztergom), Savaria (Szombathely) and Scarbantia (Sopron). Christianity spread in Pannonia in the 4th century, when it became the empire's official religion.

Migration period

In 375 AD, the nomadic Huns began invading Europe from the eastern steppes, instigating the Great Age of Migrations. In 380, the Huns penetrated into present-day Hungary, and remained an important factor in the region well into the 5th century.

Around the same time (379–395), the Roman Empire allowed the groups of Goths, Alans, Huns, Marcomanni and Quadi to settle Pannonia, which still was a Roman territory. The Visigoths, Alans, Vandals and most of the Quadi and Marcomanni, however, left this territory around 400, and moved on to western and southern Europe.

The Pannonian provinces suffered from the Migration Period from 379 onwards, the settlement of the Goth-Alan-Hun ally caused repeated serious crises and devastations, the contemporaries described it as a state of siege, Pannonia became an invasion corridor both in the north and in the south. The flight and emigration of the Romans began after two hard decades in 401, this also caused a recession in secular and ecclesiastical life. The Hun control gradually expanded over Pannonia from 410, finally the Roman Empire ratified the cession of Pannonia by treaty in 433. The flight and emigration of the Romans from Pannonia continued without interruption until the invasion of the Avars. András Mócsy assumes that the largest Roman emigration was the earliest and the 5th and 6th centuries were a phase of gradual emigration.[31]

After the Huns, namely the Hungarians experienced the bravery of the Romans and the way of their warefare, they reorganized their army, rushed the Transdanubian regions of Pannonia, took possession of them and they moved the people of their house here, then they moved towards the city of Tulln, where their opponents were assembled. Detre, Macrinus, and all the available forces of the Roman army marched against them on the field of Zeiselmauer. Both opponents attacked the opposing teams with equal fierceness. And the Huns wanted to die rather than retreat in the battle, according to Scythian custom they made a terrifying noise, they beat their drums and used every weapon against the enemy, but most of all their innumerable number of arrows. This caused the Roman troops to be confused, and so the Huns made a great slaughter among them. The morning began, and in a fierce battle which lasted until nine o'clock, the Roman army was defeated and put to flight with enormous loss.

Bishop Amantius fled around 400 to Aquileia. The emigrating Romans tooks several Christian relics and remains of Pannonian martyrs with them to Rome and to several other towns of Italy. Around 400, the inhabitants of Scarbantia (now Sopron in Hungary) fled from the invasion of the barbarians "incursio barbarorum" to Italy, and took the relics of Quirinus, the martyr bishop of Sescia (now Sisak in Croatia), from Savaria (now Szombathely in Hungary) with them. These events signified the decay of the Christian communities in Pannonia.[31]

The Huns, taking advantage of the departure of the Goths, Quadi, et al., created a significant empire in 423 based in Hungary. In 453 they reached the height of their expansion under the well-known conqueror, Attila the Hun. The empire collapsed in 455, when the Huns were defeated by the neighbouring Germanic tribes (such as the Quadi, Gepidi and Sciri).

The Gepidi (having lived to the east of the upper Tisza river since 260 AD) then moved into the eastern Carpathian Basin in 455. They ceased to exist in 567 when they were defeated by the Lombards and Avars (see below).

The Germanic Ostrogoths inhabited Pannonia, with Rome's consent, between 456 and 471.

After the Romans

Roman influence in Pannonia had begun to decline as early as the arrival of the Huns in the 4th century.

According to András Mócsy, it is not possible to prove whether the reconstruction of a church is to be attributed to barbarians or to remained Romans at the majority of places. The usage of Christian cult-buildings after the 4th century does not prove the survival of the Pannonian cult-communities because the Goths and other peoples were Arian Christians and they continued to use the dilapidated churches, however so far (1974) this usage can be proved only at the "Basilica II" in the large fortified center at Fenékpuszta (part of Keszthely in Hungary). The Keszthely culture is a special archaeological composition of the early Avar period which cannot be traced back to the local culture of the Roman period. However, based on the excavations of Fenékpuszta, a group of finds such as a gold pin with the name BONOSA proving that some ethnic group of Romans remained there. There are examples of sporadic Romans who had stayed behind in the 5th century, Saint Anthony the Hermit was born in Pannonia Valeria and as an orphaned child he was sent to his uncle, Constantius, the Bishop of Lorsch in today Germany. Later, Saint Leonianus travelled to Gaul from Savaria (now Szombathely in Hungary), Saint Martin of Braga emigrated from Pannonia to Hispania. The Lombards also took Romans along with them to Italy. The last emigration was the Syrmians to Salona to the today Croatian cost in the beginning of the 7th century.[31]

Later, Christian barbarians who migrated to the northern part of Lake Balaton established the Keszthely Culture, which disappeared by the middle of the 7th century.[33]

The first Slavs came to the region, almost certainly from the north, soon after the departure of the Ostrogoths (471 AD), together with the Lombards and Herulis. Around 530, the Germanic Lombards settled in Pannonia. They had to fight against the Gepidi and the Slavs. In 568, pushed out by the Avars, they moved into northern Italy.

The nomadic Avars arrived from Asia in the 560s, utterly destroyed the Gepidi in the east, drove away the Lombards in the west, and subjugated the Slavs, partly assimilating them. The Avars established a large empire, just as the Huns had decades prior. This empire was destroyed around 800 by Frankish and Bulgar attacks, and above all by internal feuds, however Avar population remained in numbers until the arrival of Árpád's Magyars. From 800, the whole area of Pannonian Basin was under control between two powers (East Francia and First Bulgarian Empire). Around 800, northeastern Hungary became part of the Slavic Principality of Nitra, which then became part of Great Moravia in 833.

Also, after 800, southeastern Hungary was conquered by Bulgaria. Western Hungary (Pannonia) was a tributary to the Franks. In 839 the Slavic Balaton Principality was founded in southwestern Hungary (under Frank suzerainty). During the reign of Svatopluk I northwestern Hungary was conquered by Great Moravia.[34] Pannonia remained under Frankish control until the Hungarian Conquest.[35][36]

See also

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Visy 2003, p. 81.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Visy 2003, p. 84.

- ^ Gimbutas 1991, p. 38.

- ^ Ottomány culture#Collapse and legacy

- ^ Visy 2003, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 21.

- ^ أ ب Visy 2003, p. 79.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Kovács, Tóth & Bálint 1981, p. 13.

- ^ أ ب Makkai 1994, p. 21.

- ^ أ ب Visy 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Cunliffe 1997, p. 25.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Visy 2003, p. 82.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Visy 2003, p. 83.

- ^ أ ب ت Adams 2009, p. 433.

- ^ أ ب Adams 2009, p. 436.

- ^ Cunliffe 1997, p. 43.

- ^ أ ب ت Visy 2003, p. 87.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Visy 2003, p. 88.

- ^ "Ritual and Memory: Neolithic Era and Copper Age". Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. 2022.

- ^ Bondar, Maria (2012). "Prehistoric wagon models in the Carpathian Basin, 3500-1500 BC".

- ^ "Bronzkor, p.139" (PDF).

- ^ "Hajdúsámson hoard". Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. 2022.

- ^ "Hajdúsámson sword, Hungary, 1700-1600 BC".

- ^ "Situla". Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. 2022.

- ^ "Bird-shaped lamp, 1200-900 BCE". Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. 21 September 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف Benda, Kálmán (General Editor) (1981). Magyarország történeti kronológiája – I. kötet: A kezdetektől 1526-ig. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 350. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز Kristó, Gyula (1998). Magyarország története - 895-1301 The History of Hungary - From 895 to 1301. Budapest: Osiris. p. 316. ISBN 963-379-442-0.

- ^ Török, Tibor (26 June 2023). "Integrating Linguistic, Archaeological and Genetic Perspectives Unfold the Origin of Ugrians". Genes. 14 (7): 1345. doi:10.3390/genes14071345. PMC 10379071. PMID 37510249.قالب:Creative Commons text attribution notice

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Köpeczi, Béla (General Editor); Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Szász, Zoltán; Barta, Gábor (Assistant Editor), eds. (1994). History of Transylvania. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor1-first=has generic name (help) - ^ Tóth, Endre (2001). "The Population: Dacians and Settlers". History of Transylvania Volume I. From the Beginnings to 1606 – II. Transylvania in Prehistory and Antiquity – 3. The Roman Province of Dacia (in English). New York: Columbia University Press, (The Hungarian original by Institute of History Of The Hungarian Academy of Sciences). ISBN 0-88033-479-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت Mócsy, András (1974). "The Beginning of the Dark Age". In Frere, Sheppard (ed.). Pannonia and Upper Moesia – A history of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. 339–358. ISBN 978-0-415-74582-6.

- ^ Thuróczy, János (1918). A magyarok krónikája [Chronicle of the Hungarians] (in Hungarian). Translated by Horváth, János. Magyar Helikon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Straub, Péter (1999). A Keszthely-kultúra kronológiai és etnikai hátterének újabb alternetívája [The chronological and ethnic background of the Keszthely culture, and new alternatives]. Zalai Múzeum.

- ^ Frucht, Richard C., Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Land and Culture ABC-CLIO Ltd (2004) p288

- ^ Tóth, Sándor László (1998). Levediától a Kárpát-medencéig (From Levedia to the Carpathian Basin). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 963-482-175-8.

- ^ Kristó, Gyula (1996). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. p. 229. ISBN 963-482-113-8."2500Ft – Hungarian History in the ninth Century – Hist?riaantik K?nyvesh?z". Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

Sources

- Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe. Harper San Francisco. ISBN 9780062503688.

- Cunliffe, Barry (Editor) (1997). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285441-4.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Adams, Brian (2009). "The Bükk Mountain Szeletian: Old and New Views on "Transitional" Material from the Eponymous Site of the Szeletian". In Camps, Marta; Chauhan, Parth R. (eds.). Sourcebook of Paleolithic Transitions. Springer. pp. 427–440. ISBN 978-0-387-76487-0.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kovács, Tibor; Tóth, István; Bálint, Csanád (1981). "Magyarország a honfoglalás előtt [Hungary before the Hungarian Conquest]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in الهنغارية). Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 13–52. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- Makkai, László (1994). "Hungary before the Hungarian conquest". In Sugar, Peter F.; Hanák, Péter; Frank, Tibor (eds.). A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 963-7081-01-1.

- Molnár, Miklós (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4.

- Visy, Zsolt (Editor-in-Chief) (2003). Hungarian Archaeology at the Turn of the Millennium. Ministry of National Cultural Heritage, Teleki László Foundation. ISBN 963-86291-8-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)

External links

Media related to تاريخ المجر قبل الفتح الهنغاري at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to تاريخ المجر قبل الفتح الهنغاري at Wikimedia Commons- A History of Hungary- By the Hungarian Ministry of Tourism Archived 2006-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Hungary Before the Hungarians

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- All articles lacking reliable references

- Articles lacking reliable references from May 2019

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 الهنغارية-language sources (hu)

- Hungary before the Magyars

- Hungarian prehistory

![Tisza culture ceramic altar, 5300-5200 BC.[19]](/w/images/thumb/e/e0/Tisza1.jpg/120px-Tisza1.jpg)

![Modern sculpture of a Baden culture wagon model, c. 3300 BC.[20]](/w/images/thumb/3/3a/Baden_wagon_1.jpg/120px-Baden_wagon_1.jpg)

![Bronze dagger, 2000-1800 BC[21]](/w/images/thumb/7/76/Bronzedagger.png/109px-Bronzedagger.png)

![Hajdúsámson-type sword, Ottomány culture, 1700-1600 BC.[22][23]](/w/images/thumb/9/93/Hajd%C3%BAs%C3%A1mson_type_sword.jpg/60px-Hajd%C3%BAs%C3%A1mson_type_sword.jpg)

![Bronze situla, Urnfield culture, c. 1000 BC.[24]](/w/images/thumb/4/4e/Urnfield2.jpg/109px-Urnfield2.jpg)

![Bronze oil lamp, Urnfield culture[25]](/w/images/thumb/f/f1/Bronze_vessel%2C_Hungary%2C_Bronze_Age%2C_Urnfield_culture.png/120px-Bronze_vessel%2C_Hungary%2C_Bronze_Age%2C_Urnfield_culture.png)