بون (دين)

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| ديانة بون |

|---|

|

Bon or Bön (التبتية: བོན་, وايلي: bon, ZYPY: Pön, لهجة لهاسا أصد: [pʰø̃̀]), also known as Yungdrung Bon (التبتية: གཡུང་དྲུང་བོན་, وايلي: gyung drung bon, ZYPY: Yungchung Pön, حرفياً 'eternal Bon'), is the indigenous Tibetan religion which shares many similarities and influences with Tibetan Buddhism.[1] It initially developed in the tenth and eleventh centuries[2] but retains elements from earlier Tibetan religious traditions.[3][4] Bon is a significant minority religion in Tibet, especially in the east, as well as in the surrounding Himalayan regions.[1][4]

The relationship between Bon and Tibetan Buddhism has been a subject of debate. According to the modern scholar Geoffrey Samuel, while Bon is "essentially a variant of Tibetan Buddhism" with many resemblances to Nyingma, it also preserves some genuinely ancient pre-Buddhist elements.[1] David Snellgrove likewise sees Bon as a form of Buddhism, albeit a heterodox kind.[5] Similarly, John Powers writes that "historical evidence indicates that Bön only developed as a self-conscious religious system under the influence of Buddhism".[6]

Followers of Bon, known as "Bonpos" (Wylie: bon po), believe that the religion originated in a kingdom called Zhangzhung, located around Mount Kailash in the Himalayas.[7] Bonpos hold that Bon was brought first to Zhangzhung, and then to Tibet.[8] Bonpos identify the Buddha Shenrab Miwo (Wylie: gshen rab mi bo) as Bon's founder, although no available sources establish this figure's historicity.[9]

Western scholars have posited several origins for Bon, and have used the term "Bon" in many ways. A distinction is sometimes made between an ancient Bon (وايلي: bon rnying), dating back to the pre-dynastic era before 618 CE; a classical Bon tradition (also called Yungdrung Bon – وايلي: g.yung drung bon) which emerged in the 10th and 11th centuries;[10] and "New Bon" or Bon Sar (وايلي: bon gsar), a late syncretic movement dating back to the 14th century and active in eastern Tibet.[11][12][13]

Tibetan Buddhist scholarship tends to cast Bon in a negative, adversarial light, with derogatory stories about Bon appearing in a number of Buddhist histories.[14] The Rimé movement within Tibetan Buddhism encouraged more ecumenical attitudes between Bonpos and Buddhists. Western scholars began to take Bon seriously as a religious tradition worthy of study in the 1960s, in large part inspired by the work of English scholar David Snellgrove.[15] Following the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, Bonpo scholars began to arrive in Europe and North America, encouraging interest in Bon in the West.[16] Today, a proportion of Tibetans – both in Tibet and in the Tibetan diaspora – practise Bon, and there are Bonpo centers in cities around the world.

أصل الاسم

Early Western studies of Bon relied heavily on Buddhist sources, and used the word to refer to the pre-Buddhist religion over which it was thought Buddhism triumphed.[17] Helmut Hoffmann's 1950 study of Bon characterised this religion as "animism" and "shamanism"; these characterisations have been controversial.[18] Hoffmann contrasted this animistic-shamanistic folk religion with the organised priesthood of Bonpos which developed later, Shaivism, Buddhist tantras.[19][مطلوب توضيح] Hoffman also argued that Gnosticism from the West influenced the systematised Bön religion.[20]

Hoffmann's study was foundational for Western understandings of Bon, but was challenged by a later generation of scholars influenced by David Snellgrove, who collaborated with Bonpo masters and translated Bonpo canonical texts. These scholars tended to view Bon as a heterodox form of Buddhism, transmitted separately from the two transmissions from India to Tibet that formed the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.[21] With the translation of Bonpo histories into Western languages as well as increased engagement between Bonpos and Western scholars, a shift took place in Bon studies towards engaging more thoroughly Bonpos' own histories and self-identification, recognising Bon as an independent religious tradition worthy of academic study.[22]

The term Bon has been used to refer to several different phenomena. Drawing from Buddhist sources, early Western commentators on Bon used the term for the pre-Buddhist religious practices of Tibet. These include folk religious practices, cults surrounding royalty, and divination practices. However, scholars have debated whether the term Bon should be used for all of these practices, and what their relationship is to the modern Bon religion. In an influential article, R. A. Stein used the term "the nameless religion" to refer to folk religious practices, distinguishing them from Bon.[23]

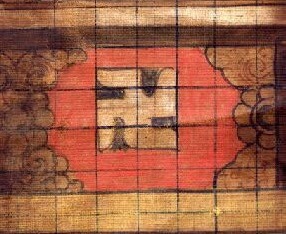

Per Kvaerne uses Bon solely to refer to a tradition he dates from tenth and eleventh centuries CE, the tradition which developed into the modern Bon religion.[24] Kvaerne identifies this tradition as "an unorthodox form of Buddhism,"[25] but other scholars such as Samten G. Karmay take seriously Bonpo narratives which define Bon as a separate tradition with an origin in the land of 'Olmo Lungring.[26] The term Yungdrung Bon (Wylie: g.yung drung bon) is sometimes used to describe this tradition. "Yungdrung" refers to the left-facing swastika, a symbol which occupies in Bon a similar place as the vajra (Wylie: rdo rje) in Tibetan Buddhism, symbolising indestructibility and eternity.[24][27] Yungdrung Bon is a universal religion, although it is mainly limited to Tibetans, with some non-Tibetan converts.

There is also a kind of local village priests which are common throughout the Himalayas that are called "bon", "lhabon" or "aya" (and bombo in Nepal). These are not part of the Bon religion proper, but are lay ritual specialists, often on a part time basis. Samuel states that it is unclear if these "bon" priests go back to the ancient period or if the term developed after Yungdrung Bon.[28]

Furthermore, the Dongba (东巴) practices of the Nakhi people and the Hangui (韩规) religion of the Pumi people are both believed to have originated from Bon.[29]

Types

As noted by Dmitry Ermakov, "the word Bön is used to denote many diverse religious and cultural traditions." Bon sources acknowledge this and Bon authors like Shardza Rinpoche (1859–1935), Pelden Tsultrim (1902–1973) and Lopön Tenzin Namdak use a classification of three types of "Bon". Modern scholars also sometimes rely on this classification, which is as follows:[11][12][13][30]

- Prehistoric Bon (Gdod ma'i bon) of Zhangzhung and Tibet. This is an ancient system of belief and ritual practice that is mostly extinct today. However, elements of it exist in various religious practices found in the Himalayas – mainly in the calling of fortune rituals (g.yang 'gug), the soul retrieval or re-call rituals (bla 'gugs) and the ransom rituals (mdos). Ermakov sees some similarities between this tradition and the Eurasian cult of the sky deer.[30]

- Eternal Bon (Yungdrung Bon), also called old Bon (Bon Nyingma), which is traced to the Buddha Tonpa Shenrab and other sages from Zhangzhung. These religions developed from the 8th to the 11th century and are similar to Nyingma Buddhism. It includes ancient elements which are pre-Buddhist (including the fortune, bla and ransom rituals).

- New Bon (Bon Sarma, Bonsar), a syncretic tradition which includes elements from Eternal Bon and Tibetan Buddhism, including the worship of the Buddhist figure Padmasambhava. This new movement dates from the 14th century and was mainly active in eastern Tibet.

Dmitry Ermakov also adds an extra category which he terms "mixed Bon" and which he defines as:[30]

... a blend of these three types of Bön in different proportions, often with the addition of elements from other religions such as Hinduism, Taoism, Himalayan Tribal religions, Native Siberian belief systems etc. Mixed Bön would include Secular Bön or the civil religion of the Himalayan borderlands studied by Charles Ramble in his The Navel of Demoness, as well as Buryatian Bѳ Murgel, from the shores of Lake Baikal, the religion of the Nakhi in Yunnan, and so on.

Traditional history

Tonpa Shenrab

From the traditional point of view of the Bon religion, Bon was the original religion of Tibet and Zhangzhung which was taught there by various Buddhas, including Tonpa Shenrab (whose name means “Supreme Holy Man”).[13][31]

Tonpa Shenrab is believed to have received the teaching from the transcendent deity Shenlha Okar in a pure realm before being reborn in the human realm with the purpose of teaching and liberating beings from the cycle of rebirth.[13] He attained Buddhahood several hundred years before Sakyamuni Buddha, in a country west of Tibet, called Olmo Lungring or Tazig (Tasi), which is difficult to identify and acts as a semi-mythical holy land in Bon (like Shambala).[13][32][33] Various dates are given for his birth date, one of which corresponds to 1917 BCE.[34] Some Bon texts also state that Sakyamuni was a later manifestation of Tonpa Shenrab.[32]

Tonpa Shenrab is said to have been born to the Tazig royal family and to have eventually become the king of the realm. He is said to be the main Buddha of our era.[35] He had numerous wives and children, constructed numerous temples and performed many rituals in order to spread Bon.[35] Like Padmasambhava, he is also held to have defeated and subjugated many demons through his magical feats, and like King Gesar, he is also believed to have led numerous campaigns against evil forces.[35]

Tonpa Shenrab is held to have visited the kingdom of Zhangzhung (an area in western Tibet around Mount Kailash),[36] where he found a people whose practice involved spiritual appeasement with animal sacrifice. He taught them to substitute offerings with symbolic animal forms made from barley flour. He only taught according to the student's capability and thus he taught these people the lower vehicles to prepare them for the study of sutra, tantra and Dzogchen in later lives.[37] It is only later in life that he became a celibate ascetic and it is during this time that he defeated his main enemy, the prince of the demons.[35]

After Tonpa Shenrab's paranirvana, his works were preserved in the language of Zhangzhung by ancient Bon siddhas.[38] Most of these teachings were said to have been lost in Tibet after the persecutions against Bon, such as during the time of Trisong Detsen.[34] Bon histories hold that some of Tonpa Shenrab's teachings were hidden away as termas and later re-discovered by Bon treasure revealers (tertons), the most important of which is Shenchen Luga (c. early 11th century).[34]

In the fourteenth century, Loden Nyingpo revealed a terma known as The Brilliance (وايلي: gzi brjid), which contained the story of Tonpa Shenrab. He was not the first Bonpo tertön, but his terma became one of the definitive scriptures of Bon.[39]

Bon histories also discuss the lives of other important religious figures, such as the Zhangzhung Dzogchen master Tapihritsa.[40]

Origin myths

Bon myth also includes other elements which are more obviously pre-Buddhist. According to Samuel, Bonpo texts include a creation narrative (in the Sipe D zop ’ug) in which a creator deity, Trigyel Kugpa, also known as Shenlha Okar, creates two eggs, a dark egg and a light egg.[41]

According to Bon scriptures, in the beginning, these two forces, light and dark, created two persons. The black man, called Nyelwa Nakpo (“Black Suffering”), created the stars and all the demons, and is responsible for evil things like droughts. The white man, Öserden (“Radiant One”), is good and virtuous. He created the sun and moon, and taught humans religion. These two forces remain in the world in an ongoing struggle of good and evil which is also fought in the heart of every person.[42]

Powers also writes that according to Bon scriptures, in the beginning, there was only emptiness, which is not a blank void but a pure potentiality. This produced five elements (earth, air, fire, water, and space) which came together into a vast "cosmic egg", from which a primordial being, Belchen Kékhö, was born.[42]

History

Pre-Buddhist Bon and the arrival of Buddhism

Little is known about the pre-Buddhist religion of ancient Tibet and scholars of Bon disagree on its nature.[43][44] Some think that Bon evolved from Zoroastrianism and others say Kashmiri Buddhism.[44]

Bon may have referred to a kind of ritual, a type of priest, or a local religion.[43] In ancient Tibet, there seem to have been a class of priests known as kushen (sku gshen, “Priests of the Body”, i.e., the king's body). This religion was eventually marginalised with the coming of Buddhism and Buddhists wrote critiques and polemics of this religion, some of which survive in manuscripts found in Dunhuang (which refer to these practices as "Bon").[13][43]

Likewise, Powers notes that early historical evidence indicates that the term "bon" originally referred to a type of priest who conducted various ceremonies, including priests of the Yarlung kings. Their rituals included propitiating local spirits and guiding the dead through ceremonies to ensure a good afterlife. Their rituals may have involved animal sacrifice, making offerings with food and drink, and burying the dead with precious jewels. The most elaborate rituals involved the Tibetan kings which had special tombs made for them.[6]

Robert Thurman describes at least one type of Bon as a "court religion" instituted "around 100 BCE" by King Pudegungyal, ninth king of the Yarlung dynasty, "perhaps derived from Iranian models", mixed with existing native traditions. It was focused on "the support of the divine legitimacy of an organized state", still relatively new in Tibet. Prominent features were "great sacrificial rituals", especially around royal coronations and burials, and "oracular rites derived from the folk religion, especially magical possessions and healings that required the priests to exhibit shamanic powers". The king was symbolised by the mountain and the priest/shaman by the sky. The religion was "somewhere between the previous "primitive animism", and the much changed later types of Bon.[45]

According to David Snellgrove, the claim that Bon came from the West into Tibet is possible, since Buddhism had already been introduced to other areas surrounding Tibet (in Central Asia) before its introduction into Tibet. As Powers writes, "since much of Central Asia at one time was Buddhist, it is very plausible that a form of Buddhism could have been transmitted to western Tibet prior to the arrival of Buddhist missionaries in the central provinces. Once established, it might then have absorbed elements of the local folk religion, eventually developing into a distinctive system incorporating features of Central Asian Buddhism and Tibetan folk religion."[36]

According to Powers, ancient Bon was closely associated with the royal cult of the kings during the early Tibetan Empire period and they performed "ceremonies to ensure the well-being of the country, guard against evil, protect the king, and enlist the help of spirits in Tibet's military ventures."[46] As Buddhism began to become a more important part of Tibet's religious life, ancient Bon and Buddhism came into conflict and there is evidence of anti-Bon polemics.[47] Some sources claim that a debate between Bonpos and Buddhists was held, and that a Tibetan king ruled Buddhism the winner, banishing Bon priests to border regions.[46] However, Gorvine also mentions that in some cases, Bon priests and Buddhist monks would perform rituals together, and thus there was also some collaboration during the initial period of Buddhist dissemination in Tibet.[47]

Bon sources place the blame of the decline of Bon on two persecutions by two Tibetan kings, Drigum Tsenpo and the Buddhist King Tri Songdetsen (r. 740–797).[48] They also state that at this time, Bon terma texts were concealed all over Tibet.[48] Bon sources generally see the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet and the subsequent period of Buddhist religious dominance as a catastrophe for the true doctrine of Bon. They see this as having been caused by demonic forces.[49] However, other more conciliatory sources also state that Tonpa Shenrab and Sakyamuni were cousins and that their teachings are essentially the same.[49]

The most influential historical figure of this period is the Bon lama Drenpa Namkha. Buddhist sources mention this figure as well and there is little doubt he was a real historical figure.[50] He is known for having ordained himself into Bon during a time when the religion was in decline and for having hidden away many Bon termas. Bon tradition holds that he was the father of another important figure, Tsewang Rigzin and some sources also claim he was the father of Padmasambhava,[50] which is unlikely as the great majority of sources say Padmasambhava was born in Swat, Pakistan. A great cult developed around Drenpa Namkha and there is a vast literature about this figure.[50]

The development of Yungdrung Bon

Yungdrung Bon (Eternal Bon) is a living tradition that developed in Tibet in the 10th and 11th centuries during the later dissemination of Buddhism (sometimes called the renaissance period) and contains many similarities to Tibetan Buddhism.[52] According to Samuel, the origins of modern Yungdrung Bon have much in common with that of the Nyingma school. Samuel traces both traditions to groups of "hereditary ritual practitioners" in Tibet which drew on Buddhist Tantra and "elements of earlier court and village-level ritual" during the 10th and 11th centuries.[53]

These figures were threatened by the arrival of new Buddhist traditions from India which had greater prestige, new ritual repertoires and the full backing of Indian Buddhist scholarship. Both Nyingmapas and Bonpos used the concept of the terma to develop and expand their traditions in competition with the Sarma schools and also to defend their school as being grounded in an authentic ancient tradition.[53] Thus, Bonpo tertons (treasure finders) like Shenchen Luga and Meuton Gongdzad Ritrod Chenpo revealed important Bon termas. An interesting figure of this era is the Dzogchen master and translator Vairotsana, who according to some sources also translated Bon texts into Tibetan and also hid some Bon termas before leaving Tibet.[54]

While Yungdrung Bon and Nyingma originated in similar circles of pre-Sarma era ritual tantric practitioners, they adopted different approaches to legitimate their traditions. Nyingma looked back to the Tibetan Empire period, and Indian Buddhist figures like Padmasambhava. Bonpos meanwhile looked further back, to Tibet's pre-Buddhist heritage, to another Buddha who was said to have lived before Sakyamuni, as well as to other masters from the kingdom of Zhangzhung.[53] The main Bonpo figures of the Tibetan renaissance period were tertons (treasure revealers) who are said to have discovered Bon texts that had been hidden away during the era of persecution. These figures include Shenchen Luga (gShen chen Klu dga'), Khutsa Dawo (Khu tsha zla 'od, b. 1024), Gyermi Nyi O (Gyer mi nyi 'od), and Zhoton Ngodrup (bZhod ston d Ngos grub, c. 12th century). Most of these figures were also laymen. It was also during this era of Bonpo renewal that the Bon Kanjur and Tenjur were compiled.[55]

Just like all forms of Tibetan Buddhism, Yungdrung Bon eventually developed a monastic tradition, with celibate monks living in various monasteries. Bon monks are called trangsong, a term that translates the Sanskrit rishi (seer, or sage).[46] A key figure in the establishment of Bon monasticism was Nyamme Sherab Gyaltsen (mNyam med Shes rab rgyal mtshan, c. 1356–1415).[56] According to Jean Luc Achard, "his insistence on Madhyamaka, logic, gradual path (lamrim) and philosophical studies has modeled the now traditional approach of practice in most Bon po monasteries."[56] His tradition emphasises the importance of combining the study of sutra, tantra and Dzogchen.[56] The most important Bon monastery is Menri monastery, which was built in 1405 in Tsang. Bon monks, like their Buddhist counterparts, study scripture, train in philosophical debate and perform rituals. However, Bon also has a strong tradition of lay yogis.[46]

The era of New Bon

"New Bon" (bonsar, or sarma Bon) is a more recent development in the Bon tradition, which is closely related to both Eternal Bon and the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism.[13][57] It is centered on the figures of Drenpa Namkha, Tsewang Rigdzin and Padmasambhava, which in this school are considered to have transmitted and written commentaries on the works of Tonpa Shenrab in around the 8th century.[13]

According to Jean Luc Achard, the New Bon movement begins in Eastern Tibet with the works of Tulku Loden Nyingpo (1360–1385), a terton who discovered the Zibji (gzi brjid), a famous Tonpa Shenrab biography.[13] His reincarnation, Techen Mishik Dorje is also known for his terma revelations.[13]

The movement continued to develop, with new Bon terma texts being revealed well into the 18th century by influential tertons like Tulku Sangye Lingpa (b. 1705) and the first Kundrol Drakpa (b. 1700).[13] New Bon figures do not consider their revelations to be truly "new", in the sense that they do not see their revelations as being ultimately different from Yungdrung Bon. However, some followers of more orthodox Yundrung Bon lineages, like the Manri tradition, saw these termas as being influenced by Buddhism. Later New Bon figures like Shardza Rinpoche (1859–1934) responded to these critiques (see his Treasury of Good Sayings, legs bshad mdzod).[13] The work of these New Bon figures led to the flourishing of New Bon in Eastern Tibet.[58]

Some Tibetan tertons like Dorje Lingpa were known to have revealed New Bon termas as well as Nyingma termas.[57]

Lobsang Yeshe (1663–1737), recognised as the 5th Panchen Lama by the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682), was a member of the Dru family, an important Bon family. Samten Karmay sees this choice as a gesture of reconciliation with Bon by the Fifth Dalai Lama (who had previously converted some Bon monasteries to Gelug ones by force). Under the Fifth Dalai Lama, Bon was also officially recognised as a Tibetan religion.[59] Bon suffered extensively during the Dzungar invasion of Tibet in 1717, when many Nyingmapas and Bonpos were executed.[60]

Modern period

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Bon tradition (both New Bon and Eternal Bon lineages) flourished in Eastern Tibet, led by charismatic Bonpo lamas like bDe ch en gling pa, d Bal gter sTag s lag can (bsTan 'dzin dbang rgyal), gSang sngags gling pa, and Shardza Rinpoche.[61]

Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen (1859–1933) was a particularly important Bon master of this era, whose collected writings comprise up to eighteen volumes (or sometimes twenty).[62] According to William M. Gorvine, this figure is "the Bon religion's most renowned and influential luminary of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."[63] He was associated with the orthodox Eternal Bon Manri monastery tradition as well as with New Bon figures like the 5th and 6th Kun grol incarnations, gSang sngags gling pa (b. 1864) and bDe chen gling pa (1833–1893) as well as with dBal bon sTag lag ca n, bsTan ' d zin dbang rgyal (b. 1832). These figures maintained the orthodox Manri tradition of Eternal Bon, while also holding New Bon terma lineages.[64]

Shardza Rinpoche is also known to have had connections with the non-sectarian Buddhist lamas of the Rime movement and to have taught both Buddhists and Bonpos.[65][66]

Shardza Rinpoche had many disciples, including his nephew Lodro Gyatso (1915–1954) who led the lineage and Shardza's hermitage and college, after Shardza's passing.[67][68] His disciple Kagya Khyungtrul Jigmey Namkha trained many practitioners to be learned in not only the Bon religion, but in all Tibetan sciences.[69] More than three hundred Bon monasteries had been established in Tibet before Chinese occupation. Of these, Menri Monastery and Shurishing Yungdrung Dungdrakling Monastery were the two principal monastic universities for the study and practice of Bon.

Present situation

In 2019, scholars estimate that there were 400,000 Bon followers in the Tibetan plateau.[70] When Tibet was invaded by the People's Republic of China, there were approximately 300 Bon monasteries in Tibet and the rest of western China. Bon suffered the same fate as Tibetan Buddhism did during the Chinese Cultural revolution, though their monasteries were allowed to rebuild after 1980.[71]

The present spiritual head of the Bon is Menri Trizin Rinpoché, successor of Lungtok Tenpai Nyima (1929–2017), the thirty-fourth Abbot of Menri Monastery (destroyed in the Cultural Revolution, but now rebuilt), who now presides over Pal Shen-ten Menri Ling in Dolanji in Himachal Pradesh, India. The 33rd lineage holder of Menri Monastery, Menri Trizin Lungtog Tenpei Nyima and Lopön Tenzin Namdak are important current lineage holders of Bon.

A number of Bon establishments also exist in Nepal; Triten Norbutse Bonpo Monastery is one on the western outskirts of Kathmandu. Bon's leading monastery in India is the refounded Menri Monastery in Dolanji, Himachal Pradesh.

Official recognition

Bonpos remained a stigmatised and marginalised group until 1979, when they sent representatives to Dharamshala and the 14th Dalai Lama, who advised the Parliament of the Central Tibetan Administration to accept Bon members. Before this recognition, during the previous twenty years, the Bon community had received none of the financial support which was channelled through the Dalai Lama's office and were often neglected and treated dismissively in the Tibetan refugee community.[72]

Since 1979, Bon has had official recognition of its status as a religious group, with the same rights as the Buddhist schools. This was re-stated in 1987 by the Dalai Lama, who also forbade discrimination against the Bonpos, stating that it was both undemocratic and self-defeating. He even donned Bon ritual paraphernalia, emphasising "the religious equality of the Bon faith".[73] The Dalai Lama now sees Bon as the fifth Tibetan religion and has given Bonpos representation on the Council of Religious Affairs at Dharamsala.[57]

However, Tibetans still differentiate between Bon and Buddhism, referring to members of the Nyingma, Shakya, Kagyu and Gelug schools as nangpa, meaning "insiders", but to practitioners of Bon as "Bonpo", or even chipa ("outsiders").[74][75]

Teachings

According to Samuel, the teachings of Bon closely resemble those of Tibetan Buddhism, especially those of the Nyingma school. Bon monasticism has also developed a philosophical and debate tradition which is modelled on the tradition of the Gelug school.[76] Like Buddhism, Bon teachings see the world as a place of suffering and seek spiritual liberation. They teach karma and rebirth as well as the six realms of existence found in Buddhism.[77]

Bon lamas and monks fill similar roles as those of Tibetan Buddhist lamas and the deities and rituals of Bon often resemble Buddhist ones, even if their names and iconography differ in other respects.[76] For example, the Bon deity Phurba is almost the same deity as Vajrakilaya, while Chamma closely resembles Tara.[76]

Per Kværne writes that, at first glance, Bon "appear to be nearly indistinguishable from Buddhism with respect to its doctrines, monastic life, rituals, and meditational practices."[78] However, both religions agree that they are distinct, and a central distinction is that Bon's source of religious authority is not the Indian Buddhist tradition, but what it considers to be the eternal religion which it received from Zhangzhung (in Western Tibet) and ultimately derives from land called Tazik where Tonpa Shenrab lived, ruled as king and taught Bon.[78] Bon also includes many rituals and concerns that are not as common in Tibetan Buddhism. Many of these are worldly and pragmatic, such as divination rituals, funerary rituals that are meant to guide a deceased person's consciousness to higher realms and appeasing local deities through ransom rituals.[79]

In the Bon worldview, the term "Bon" means “truth,” “reality,” and “the true doctrine.” The Bon religion, which is revealed by enlightened beings, provides ways of dealing with the mundane world as well as a path to spiritual liberation.[5] Bon doctrine is generally classified in various ways, including the "nine ways" and the four portals and the fifth, the treasury.

Worldview

According to Bon, all of reality is pervaded by a transcendent principle, which has a male aspect called Kuntuzangpo (All-Good) and a female aspect called Kuntuzangmo. This principle is an empty dynamic potentiality. It is also identified with what is called the "bon body" (bon sku), which is the true nature of all phenomena and is similar to the Buddhist idea of the Dharmakaya, as well as with the "bon nature" (bon nyid), which is similar to "Buddha nature". This ultimate principle is the source of all reality and to achieve spiritual liberation, one must have insight into this ultimate nature.[42]

According to John Myrdhin Reynolds, Bonpo Dzogchen is said to reveal one's Primordial State (ye gzhi) or Natural State (gnas-lugs) which is described in terms of intrinsic primordial purity (ka-dag) and spontaneous perfection in manifestation (lhun-grub).[57]

The Bon Dzogchen understanding of reality is explained by Powers as follows:

In Bön Dzogchen texts, the world is said to be an emanation of luminous mind. All the phenomena of experience are its illusory projections, which have their being in mind itself. Mind in turn is part of the primordial basis of all reality, called “bön nature.” This exists in the form of multicolored light and pervades all of reality, which is merely its manifestation. Thus Shardza Tashi Gyaltsen contends that everything exists in dependence upon mind, which is an expression of the bön nature...mind is a primordially pure entity that is co-extensive with bön nature, an all-pervasive reality that is only perceived by those who have eliminated adventitious mental afflictions and actualized the luminous potentiality of mind. Those who attain awakening transform themselves into variegated light in the form of the rainbow body, after which their physical forms dissolve, leaving nothing behind. Both cyclic existence and nirvana are mind, the only difference being that those who have attained nirvana have eliminated illusory afflictions, and so their cognitive streams are manifested as clear light, while beings caught up in cyclic existence fail to recognize the luminous nature of mind and so are plagued by its illusory creations.[80]

Classification of the teachings

According to John Myrdhin Reynolds, the main Bon teachings are classified into three main schemas:[57]

- The Nine Successive Vehicles to Enlightenment (theg-pa rim dgu);

- Four Portals of Bon and the fifth which is the Treasury (sgo bzhi mdzod lnga);

- The Three Cycles of Precepts that are Outer, Inner, and Secret (bka' phyi nang gsang skor gsum).

The Nine Ways or Vehicles

Samuel notes that Bon tends to be more accepting and explicit in their embrace of the practical side of life (and the importance of life rituals and worldly activities) which falls under the "Bon of cause" division of "the Nine Ways of Bon" (bon theg pa rim dgu). This schema includes all the teachings of Bon and divides them into nine main classes, which are as follows:[81][82]

- Way of Prediction (phyva gshen theg pa) codifies ritual, divination, medicine, and astrology;

- Way of the Visual World (snang shen theg pa) teaches rituals for local gods and spirits for good fortune

- Way of Magic ('phrul gshen theg pa) explains the magical excorcistic rites for the destruction of adverse entities.

- Way of Life (srid gshen theg pa) details funeral and death rituals as well as ways to protect the life force of the living

- Way of a Lay Follower (dge bsnyen theg pa) lay morality, contains the ten principles for wholesome activity as well as worldly life rituals

- Way of an Ascetic (drang srong theg pa) or "Swastika Bon" focuses on ascetic practice, meditation and monastic life;

- Way of Primordial Sound (a dkar theg pa) or the Way of the White A, this refers to tantric practices and secret mantras (gsang sngags);

- Way of Primordial Shen, (ye gshen theg pa) refers to certain special yogic methods. This corresponds to the Nyingma school's Anuyoga.

- The Supreme Way (bla med theg pa), or The Way of Dzogchen (Great Perfection). Like the Nyingmapas, Bonpos consider Dzogchen to be the superior meditative path.

Traditionally, the Nine Ways are taught in three versions: in the Central, Northern and Southern treasures. The Central treasure is closest to Nyingma Nine Yānas teaching and the Northern treasure is lost. Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche elaborated the Southern treasure with shamanism.[37]

The nine ways are classified into two main divisions in the "Southern Treasure" terma tradition:[81][57]

- "Bon of Cause" (rgyu), comprises the first four of the above;

- "Bon of the Effect" ('bras bu) includes the fifth through ninth, the superior path being the Way of Dzogchen (as in the Nyingma school).

The Four Portals and the Fifth, the Treasury

This classification, called The Four Portals and the Fifth, the Treasury (sgo bzhi mdzod lnga), is a different and independent system of classification.[57] The main sets of teachings here are divided up as follows:[57]

- The Bon of "the White Waters" containing the Fierce Mantras (chab dkar drag-po sngags kyi bon) deals with tantric or esoteric matters, mainly fierce or wrathful practices and deities.

- The Bon of "the Black Waters" for the continuity of existence (chab nag srid-pa rgyud kyi bon) concerns divination, magic, funeral rites, purification rituals and ransom rituals.

- The Bon of the Extensive Prajnaparamita from the country of Phanyul ('phan-yul rgyas-pa 'bum gyi bon) includes teachings on lay and monastic ethics, as well as expositions of Prajnaparamita philosophy.

- The Bon of the Scriptures and the Secret Oral Instructions of the Masters (dpon-gsas man-ngag lung gi bon) deals mainly with Dzogchen teachings.

- The Bon of the Treasury which is of the highest purity and is all-inclusive (gtsang mtho-thog spyi-rgyug mdzod kyi bon), this is an anthology of the salient items of the Four Portals.

The Three Cycles

The Three Cycles of Precepts that are Outer, Inner, and Secret (bka' phyi nang gsang skor gsum) are:[57]

- The Outer Cycle (phyi skor) deals with sutra teachings on the path of renunciation.

- The Inner Cycle (nang skor) contains Tantric teachings (rgyud-lugs) and is known as the path of transformation (sgyur lam).

- The Secret Cycle (gsang skor) contains the Dzogchen intimate instructions (man-ngag) and is known as the Path of Self-Liberation (grol lam).

Traditions of Bon Dzogchen

There are three main Bon Dzogchen traditions:[83][57][84]

- The Zhang-zhung Aural Lineage (Zhang-zhung nyen-gyu) – This tradition is ultimately traced to the primordial Buddha Kuntu Zangpo, who taught it to nine Sugatas, the last being Sangwa Düpa. These teachings were then passed down by twenty four Dzogchen masters in Tazik and Zhangzhung, all of which are said to have attained rainbow body.[85] The lineage eventually reached the 7th century siddha Tapihritsa, the last of the 24 masters. He later appeared to the 8th century Zhangzhung siddha Gyerpung Nangzher Lödpo, who was in retreat near Darok Lake, and gave him a direct introduction to Dzogchen.[85] Gyerpung Nangzher Lödpo transmitted the teachings to numerous disciples who also wrote the teachings down. This lineage continued until it reached Pön-gyal Tsänpo, who translated these works into Tibetan from the language of Zhangzhung.[85]

- A-khrid ("The Teaching Leading to the Primordial State i.e. A") – This tradition was founded by Meuton Gongdzad Ritrod Chenpo ('The Great Hermit Meditation-Treasury of the family of rMe'u', c. 11th century). These teachings are divided into three sections dealing with the view (lta-ba), the meditation (sgom-pa), and the conduct (spyod-pa) and is structured into a set of eighty meditation sessions which extend over several weeks. Later figures like Aza Lodo Gyaltsan and Druchen Gyalwa Yungdrung condensed the practices down to a smaller number of sessions. The great Bonpo master Shardza Rinpoche wrote extensive commentaries on the A-khrid system and its associated dark retreat practice.[57]

- Dzogchen Yangtse Longchen – This system is based on a terma named the rDzogs-chen yang-rtse'i klong-chen ("the Great Vast Expanse of the Highest Peak which is the Great Perfection,") which was discovered by Zhodton Ngodrub Dragpa in 1080 (inside of a statue of Vairocana). The terma is attributed to the eighth century Bonpo master Lishu Tagrin.[57]

Donnatella Rossi also mentions two more important cycles of Bon Dzogchen teachings:[86]

- Ye khri mtha' sel, also known as the Indian Cycle (rgya gar gyi skor), which is attributed to the eighth century Zhangzhung master Dranpa Namkha and is said to have been transmitted in the 11th century to Lung Bon lHa gnyan by a miraculous apparition of Dranpa Namkha's son.

- Byang chub sems gab pa dgu skor, which is classified as an important Southern Treasure text and was discovered by Shenchen Luga (996–1035), a major figure of the later diffusion of Bon.

Pantheon

Enlightened beings

Bon deities share some similarities to Buddhist Mahayana deities and some are also called "Buddhas" (sanggye), but they also have unique names, iconography and mantras.[87] As in Tibetan Buddhism, Bon deities can be "peaceful" or "wrathful".[88]

The most important of the peaceful deities are the "Four Transcendent Lords, Deshek Tsozhi (bDer gshegs gtso bzhi)."[88] Each of these four beings has many different forms and manifestations.[88] These are:[88]

- "The Mother" Satrig Ersang, a female Buddha whose name means wisdom and who is similar to Prajnaparamita (and is also yellow in colour). Her "five heroic syllables" are: SRUM, GAM, RAM, YAM, OM.[89] One of her most important manifestations is Sherab Chamma (loving lady of wisdom), a female bodhisattva like being.

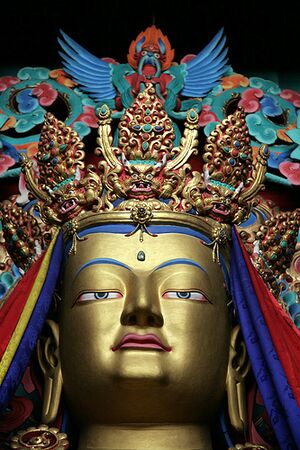

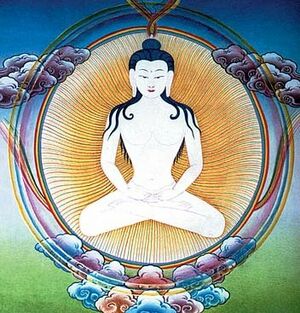

- "The God" Shenlha Ökar (wisdom priest of white light) or Shiwa Ökar (peaceful white light), a deity of wisdom light and compassion, whose main color is white. He is associated with the Dharmakaya. Kvaerne sees some similarities with Amitabha.[90] Another important Dharmakaya deity is Kuntuzangpo (Samantabhadra, All Good), the primordial Buddha, which serves a similar function to the figure of the same name in the Nyingma school Both Kuntuzangpo and Shenlha Ökar are seen as personifications of the 'Body of Bon', or Ultimate Reality.[91] In Bon, Kuntunzangpo is often presented in a slightly different form called Kunzang Akor ('the All-Good, Cycle of A'), depicted seated in meditation with a letter A in his breast.[91]

- "The Procreator" (sipa), Sangpo Bumtri. He is the being who brings forth the beings of this world and plays an important role in Bon cosmogonic myths. He is associated with the sambhogakaya.[92]

- "The Teacher" Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche (meaning: Supreme Priest, Great Man). He is associated with the nirmanakaya and is the present teacher of Bon in this era.[93]

Bon Yidams (meditation or tutelary deities) are those deities which are often used in meditative tantric practice and are the mainly fierce or wrathful forms. These class of deities resemble Buddhist yidams like Chakrasamvara and Hevajra. It includes figures like Magyu Sangchog Tartug ('Supreme Secret of Mother Tantras, Attaining the Limit'), Trowo Tsochog Khagying ('Wrathful One, Supreme Lord Towering in the Sky'), Welse Ngampa ('Fierce Piercing Deity'), and Meri ('Mountain of Fire').[94] The Bonpos also have a tantric tradition of a deity called Purpa, which is very similar to the Nyingma deity Vajrakilaya.[95]

Like the Buddhists, the Bon pantheon also includes various protector deities, siddhas (perfected ones), lamas (teachers) and dakinis. Some key figures are Drenpa Namkha (a major 8th century Bon lama whose name is also mentioned in Buddhist sources), the sage Takla Mebar (a disciple of Tonpa Shenrab), Sangwa Dupa (a sage from Tazik), Zangsa Ringtsun (Auspicious Lady of Long Life).[96]

Worldly gods and spirits

The Bon cosmos contains numerous other deities, including Shangpo and Chucham (a goddess of water) who produced nine gods and goddesses. There is also the 360 Kékhö, who live on the mount Tisé (Kailash) and the 360 Werma deities. These are associated with the 360 days of the year.[97]

Another set of deities are the White Old Man, a sky god, and his consort. They are known by a few different names, such as the Gyalpo Pehar called “King Pehar” (وايلي: pe har rgyal po). Pehar is featured as a protecting deity of Zhangzhung, the center of the Bon religion. Reportedly, Pehar is related to celestial heavens and the sky in general. In early Buddhist times, Pehar transmogrified into a shamanic bird to adapt to the bird motifs of shamanism. Pehar's consort is a female deity known by one of her names as Düza Minkar (وايلي: bdud gza smin dkar).[98]

Bonpos cultivate household gods in addition to other deities and the layout of their homes may include various seats for protector deities.[99]

Chinese influence is also seen is some of the deities worshiped in Bon. For example, Confucius is worshipped in Bon as a holy king and master of magic, divination and astrology. He is also seen as being a reincarnation of Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, the legendary founder of Bon.[100]

In the Balti version of Bon in Baltistan, deities such as lha (gods), klu (serpents or dragons) and lhamo (goddesses) are worshipped, and many legends about these deities still exist among the local population.

Bon literature

Bon texts can be divided into translations of teachings (the words of Buddha Shenrab, found in the Bon Kanjur) and translations of treatises (philosophical and commentarial texts, the Bon Tenjur).[77] The Bon Kanjur comprises four main categories: the Sutras (mdo), the Perfection of Wisdom Teachings ('bum), the Tantras (rgyud) and Higher Knowledge (mdzod, 'Treasure-house'), which deals with the supreme forms of meditation.[101] The Tenjur material is classified into three main categories according to Kvaerne: "'External', including commentaries on canonical texts dealing with monastic discipline, morality; metaphysics and the biographies of Tonpa Shenrap; 'Internal', comprising the commentaries on the Tantras including rituals focusing on the tantric deities and the cult of dakinis, goddesses whose task it is to protect the Doctrine, and worldly rituals of magic and divination; and finally 'Secret', a section that deals with meditational practices."[101]

Besides these, the Bon canon includes material on rituals, arts and crafts, logic, medicine, poetry and narrative. According to Powers, Bon literature includes numerous ritual and liturgical treatises, which share some similarities to Tibetan Buddhist ritual.[102] According to Per Kvaerne, "while no precise date for the formation of the Bonpo Kanjur can be ascertained at present...it does not seem to contain texts which have come to light later than 1386. A reasonable surmise would be that the Bonpo Kanjur was assembled by 1450."[101]

According to Samuel, Bon texts are similar to Buddhist texts and thus suggest "a considerable amount of borrowing between the two traditions in the tenth and eleventh centuries. While it has generally been assumed that this borrowing proceeds from Buddhist to Bonpo, and this seems to have been the case for the Phurba practice, some of it may well have been in the opposite direction."[95] Powers similarly notes that "many Bön scriptures are nearly identical to texts in the Buddhist canon, but often have different titles and Bön technical terms" and "only a few Bön texts that seem to predate Buddhism."[77] While Western scholars initially assumed that this similarity with Buddhist texts was mere plagiarism, the work of Snellgrove and others have reassessed this view and now most scholars of Bon hold that in many cases, Buddhist texts borrow and reproduce Bon texts. Per Kværne writes that "this does not mean that Bon was not at some stage powerfully influenced by Buddhism; but once the two religions, Bon and Buddhism, were established as rival traditions in Tibet, their relationship was a complicated one of mutual influence.[78]

Regarding the current status of the Bon canon, Powers writes that:

The Bön canon today consists of about three hundred volumes, which were carved onto wood blocks around the middle of the nineteenth century and stored in Trochu in eastern Tibet. Copies of the canon were printed until the 1950s, but the blocks were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, although it appears that most of the texts were brought to India or hidden in Tibet.[77]

Termas

The largest part of the Bon canon is made up of numerous termas (treasure texts), which were believed to have been hidden away during the period of persecution and to have begun to be discovered during the 10th century.[101] Bonpos hold that their termas were hidden by masters like Drenpa Namkha during the period of decline and persecution under King Trisong Detsen, and then were rediscovered by later Bon tertons (treasure discoverers).[102]

The three principal terma of Yungdrung Bon are:[103]

- the "Northern Treasure" (وايلي: byang gter), compiled from texts revealed in Zhangzhung and northern Tibet

- the "Central Treasure" (وايلي: dbus gter), from Central Tibet

- the "Southern Treasure" (وايلي: lho gter), revealed in Bhutan and Southern Tibet.

Three Bon scriptures—mdo 'dus, gzer mig, and gzi brjid—relate the mythos of Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche. The Bonpos regard the first two as gter ma rediscovered around the tenth and eleventh centuries and the last as nyan brgyud (oral transmission) dictated by Loden Nyingpo, who lived in the fourteenth century.[104]

A Cavern of Treasures (التبتية: མཛོད་ཕུག, وايلي: mdzod phug) is a Bon terma uncovered by Shenchen Luga (التبتية: གཤེན་ཆེན་ཀླུ་དགའ, وايلي: gshen chen klu dga') in the early 11th century which is an important source for the study of the Zhang-Zhung language.[105]

The main Bon great perfection teachings are found in terma texts called The Three Cycles of Revelation. The primary Bon Dzogchen text is The Golden Tortoise, which was revealed by Ngödrup Drakpa (c. 11th century). According to Samten Karmay, these teachings are similar to those of the Semde class in Nyingma.[106] According to Jean Luc Achard, the main Dzogchen cycle studied and practised in contemporary Bon is The Oral Transmission of the Great Perfection in Zhangzhung (rDzogs pa chen po zhang zhung snyan rgyud), a cycle which includes teachings on the Dzogchen practices of trekcho and thogal (though it uses different terms to refer to these practices) and is attributed to the Zhangzhung sage Tapihritsa.[107]

See also

References

- ^ أ ب ت Samuel 2012, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Kværne, Per (1995). The Bon Religion of Tibet: The Iconography of a Living Tradition. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala. p. 13. ISBN 9781570621864. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

According to its own historical perspective, Bon was introduced into Tibet many centuries before Buddhism and enjoyed royal patronage until it was finally supplanted by the 'false religion' (i.e. Buddhism) from India ...

- ^ Samuel 2012, p. 220.

- ^ أ ب Kvaerne 1996, pp. 9–10.

- ^ أ ب Powers 2007, pp. 500–501

- ^ أ ب Powers (2007), p. 497.

- ^ Karmay, Samten G., "Extract from 'A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon'", in Alex McKay, ed. History of Tibet, Volume 1 (New York: Routledge, 2003), 496–9.

- ^ Namdak, Lopon Tenzin, Heart Drops of Dharmakaya (Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 2002).

- ^ Karmay, 499.

- ^

Kang, Xiaofei; Sutton, Donald S. (2016). "Garrison City in the Ming: Indigenes and the State in Greater Songpan". Contesting the Yellow Dragon: Ethnicity, Religion, and the State in the Sino-Tibetan Borderland, 1379–2009. Religion in Chinese Societies ISSN 1877-6264, Volume 10. Leiden: Brill. p. 32. ISBN 9789004319233. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

[...] Yungdrung Bon [...] emerged in the 10th and 11th centuries, along with the second rise of Buddhism in Tibet, and continues as a minority practice among Tibetans in both the People's Republic and overseas.

- ^ أ ب Achard, Jean-Luc (2015). "On the Canon Bönpo of the Collège de France Institute of Tibetan Studies". La Lettre du Collège de France. Collège de France (9): 108–109. doi:10.4000/lettre-cdf.2225. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- ^ أ ب Keown, Damien (2003). Oxford Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860560-9.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Achard, Jean Luc. "The Three Kinds of Bon (The Treasury of Lives: A Biographical Encyclopedia of Tibet, Inner Asia and the Himalayan Region)". The Treasury of Lives (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Samuel, Geoffrey, "Shamanism, Bon, and Tibetan Religion," in Alex McKay, ed. History of Tibet, Volume 1 (New York: Routledge, 2003), 462–3.

- ^ Samuel, 465-7.

- ^ Samuel, 465.

- ^ Kvaerne, Per, "The Study of Bon in the West: Past, present, and future", in Alex McKay, ed. History of Tibet, Volume 1 (New York: Routledge, 2003), 473–4.

- ^ Kvaerne, "Study of Bon in the West," 473-4.

- ^ Kvaerne, "Study of Bon in the West," 474.

- ^ Wedderburn, A.J.M. (2011). Baptism and Resurrection: Studies in Pauline Theology against its Graeco-Roman Background. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-61097-087-7. Retrieved 2024-05-10.

- ^ Kvaerne, "Study of Bon in the West," 476

- ^ Kvaerne, "Study of Bon in the West," 478.

- ^ Kvaerne, Per, "Extract from The Bon Religion of Tibet", in Alex McKay, ed. History of Tibet, Volume 1 (New York: Routledge, 2003), 486.

- ^ أ ب Kvaerne, "Extract from The Bon Religion of Tibet", 486.

- ^ Kvaerne, "Extract from The Bon Religion of Tibet", 486."

- ^ Karmay, "Extract from 'A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon'", 496-9.

- ^ William M. Johnston (2000). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Taylor & Francis. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2.

- ^ Samuel 2012, p. 230.

- ^ "普米韩规古籍调研报告". Pumichina.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-14. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ أ ب ت Ermakov, Dmitry (2011) Bön as a multifaceted phenomenon:looking beyond Tibet to the cultural and religious traditions of Eurasia, Presented at Bon, Zhang Zhung and Early Tibet Conference, SOAS, London, 10 September 2011

- ^ Powers 2007, p. 503.

- ^ أ ب Samuel 2012, p. 221.

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, p. 14.

- ^ أ ب ت Samuel 2012, p. 227.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Kvaerne 1996, p. 17.

- ^ أ ب Powers 2007, p. 502.

- ^ أ ب Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, Healing with Form, Energy, and Light. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-55939-176-6, pp. xx

- ^ Achard, Jean Luc. "The Three Kinds of Bon (The Treasury of Lives: A Biographical Encyclopedia of Tibet, Inner Asia and the Himalayan Region)". The Treasury of Lives (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Van Schaik, Sam. Tibet: A History. Yale University Press 2011, pages 99–100.

- ^ Wangyal (2002).

- ^ Samuel 2012, p. 225.

- ^ أ ب ت Powers 2007, p. 506.

- ^ أ ب ت Schaik, Sam van (2009-08-24). "Buddhism and Bon IV: What is bon anyway?". early Tibet (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ أ ب The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Translated by Dorje, Gyurnme; Coleman, Graham; Jinpa, Thupten. Introductory commentary by the 14th Dalai Lama (First American ed.). New York: Viking Press. 2005. p. 449. ISBN 0-670-85886-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Thurman in: Rhie, Marylin and Thurman, Robert (eds):Wisdom And Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet, p. 21-22, 1991, Harry N. Abrams, New York (with 3 institutions), ISBN 0810925265

- ^ أ ب ت ث Powers 2007, p. 505.

- ^ أ ب Gorvine 2018, p. 21.

- ^ أ ب Kværne, Per. "Bon Rescues Dharma" in Donald S. Lopez (Jr.) (ed.) (1998). Religions Of Tibet In Practice, p. 99.

- ^ أ ب Kvaerne 1996, p. 22.

- ^ أ ب ت Kvaerne 1996, p. 119.

- ^ "Biography Of Shenchen Luga". collab.its.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, p. 10.

- ^ أ ب ت Samuel 2012, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Rossi 2000, p. 23.

- ^ Achard (2008), p. xix.

- ^ أ ب ت Achard 2008, p. xix.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Myrdhin Reynolds, John. "Vajranatha.com | Bonpo and Nyingmapa Traditions of Dzogchen Meditation" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ Achard 2008, p. xxi.

- ^ Karmay, Samten G. (2005), The Great Fifth, pp. 12–13, http://www.iias.nl/nl/39/IIAS_NL39_1213.pdf, retrieved on 2010-05-24

- ^ Norbu, Namkhai. (1980). “Bon and Bonpos”. Tibetan Review, December, 1980, p. 8.

- ^ Achard 2008, p. xx

- ^ Achard 2008, p. xxiii.

- ^ Gorvine 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Achard 2008, pp. xxi–xxii.

- ^ Samuel 2012, p. 228.

- ^ Gorvine 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Gorvine 2018, p. 4.

- ^ Achard 2008, p. 113

- ^ "History of the YungDrung Bön Tradition". Sherab Chamma Ling (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ "Tibet". United States Department of State. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ Samuel 2012, p. 231.

- ^ Samuel 2012, p. 222.

- ^ Kværne, Per and Rinzin Thargyal. (1993). Bon, Buddhism and Democracy: The Building of a Tibetan National Identity, pp. 45–46. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. ISBN 978-87-87062-25-1.

- ^ "Bon Children's Home In Dolanji and Polish Aid Foundation For Children of Tibet". Nyatri.org. 4 July 2023.

- ^ "About the Bon: Bon Culture". Bonfuturefund.org. Archived from the original on 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ أ ب ت Samuel 2012, pp. 223–224

- ^ أ ب ت ث Powers 2007, p. 508.

- ^ أ ب ت Kværne, Per. "Bon Rescues Dharma" in Donald S. Lopez (Jr.) (ed.) (1998). Religions Of Tibet In Practice, p. 98.

- ^ Gorvine 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Powers 2007, p. 511.

- ^ أ ب Samuel 2012, p. 226

- ^ Powers 2007, p. 509

- ^ Bru-sgom Rgyal-ba-gʼyung-drung (1996), The Stages of A-khrid Meditation: Dzogchen Practice of the Bon Tradition, translated by Per Kvaerne and Thupten K. Rikey, pp. x–xiii. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives

- ^ Rossi 2000, pp. 26–29

- ^ أ ب ت Myrdhin Reynolds, John. "Vajranatha.com | Oral Tradition from Zhang-Zhung" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ^ Rossi 2000, pp. 29–30

- ^ Powers 2007, pp. 510–511

- ^ أ ب ت ث Kvaerne 1996, p. 24.

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, p. 25.

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, pp. 25–26.

- ^ أ ب Kvaerne 1996, p. 29

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, p. 26.

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, pp. 74–86.

- ^ أ ب Samuel 2012, p. 224

- ^ Kvaerne 1996, pp. 117-

- ^ Powers 2007, p. 507.

- ^ Hummel, Siegbert. “PE-HAR.” East and West 13, no. 4 (1962): 313–6.

- ^ "Tibetan Buddhism – Unit One" (PDF). Sharpham Trust. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

Everyday [ك] the man of the house would invoke this god and burn juniper wood and leaves to placate him.

- ^ Lin, Shen-yu (2005). "The Tibetan Image of Confucius" (PDF). Revue d'Études Tibétaines (12): 105–129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Kvaerne 1996, p. 21.

- ^ أ ب Powers 2007, p. 510

- ^ M. Alejandro Chaoul-Reich (2000). "Bön Monasticism". Cited in: William M. Johnston (author, editor) (2000). Encyclopedia of monasticism, Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-57958-090-4, ISBN 978-1-57958-090-2. Source: [1] (accessed: Saturday April 24, 2010), p.171

- ^ Karmay, Samten G. A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon, The Arrow and the Spindle. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point. pp. 108–113. [originally published in Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko, No. 33. Tokyo, 1975.]

- ^ Berzin, Alexander (2005). The Four Immeasurable Attitudes in Hinayana, Mahayana, and Bon. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Powers 2007, p. 510.

- ^ Achard, Jean-Luc (2017). The Six Lamps: Secret Dzogchen Instructions of the Bön Tradition, pp. vii – 7. Simon and Schuster.

Sources

- Achard, Jean-Luc (2008). Enlightened Rainbows – The Life and Works of Shardza Tashi Gyeltsen Brill's Tibetan Studies Library, Brill Academic Publishers.

- Donald S. Lopez (Jr.) (ed.) (1998). Religions Of Tibet In Practice. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Limited.

- Gorvine, William M. (2018). Envisioning a Tibetan Luminary: The Life of a Modern Bönpo Saint. Oxford University Press.

- Karmay, Samten G. (1975). A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon. Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko, No. 33, pp. 171–218. Tokyo, Japan: Tōyō Bunko.

- Kvaerne, Per (1996). The Bon Religion of Tibet, The Iconography of a Living Tradition. Shambhala

- Powers, John (2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition. Snow Lion Publications.

- Rossi, Donnatella (2000). The Philosophical View of the Great Perfection in the Tibetan Bon Religion. Shambhala Publications

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2012). Introducing Tibetan Buddhism. Routledge.

- Wangyal, Tenzin (2002). Healing with form, energy and light. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-176-6.

Further reading

- Allen, Charles. (1999). The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History. Little, Brown and Company. Reprint: Abacus, London. 2000. ISBN 0-349-11142-1.

- Baumer, Christopher. Bon: Tibet's Ancient Religion. Ilford: Wisdom, 2002. ISBN 978-974-524-011-7.

- Bellezza, John Vincent. Spirit Mediums, Sacred Mountains and Related Bön Textual Traditions in Upper Tibet. Boston: Brill, 2005.

- Bellezza, John Vincent. “gShen-rab Myi-bo, His life and times according to Tibet's earliest literary sources”, Revue d’études tibétaines 19 (October 2010): 31–118.

- Ermakov, Dmitry. Bѳ and Bön: Ancient Shamanic Traditions of Siberia and Tibet in their Relation to the Teachings of a Central Asian Buddha. Kathmandu: Vajra Publications, 2008.

- Günther, Herbert V. (1996). The Teachings of Padmasambhava. Leiden–Boston: Brill.

- Gyaltsen, Shardza Tashi. Heart drops of Dharmakaya: Dzogchen practice of the Bon tradition, 2nd edn. Trans. by Lonpon Tenzin Namdak. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion, 2002.

- Hummel, Siegbert. “PE-HAR.” East and West 13, no. 4 (1962): 313–6.

- Jinpa, Gelek, Charles Ramble, & V. Carroll Dunham. Sacred Landscape and Pilgrimage in Tibet: in Search of the Lost Kingdom of Bon. New York–London: Abbeville, 2005. ISBN 0-7892-0856-3

- Kind, Marietta. The Bon Landscape of Dolpo. Pilgrimages, Monasteries, Biographies and the Emergence of Bon. Berne, 2012, ISBN 978-3-0343-0690-4.

- Lhagyal, Dondrup, et al. A Survey of Bonpo Monasteries and Temples in Tibet and the Himalaya. Osaka 2003, ISBN 4901906100.

- Martin, Dean. “'Ol-mo-lung-ring, the Original Holy Place”, Sacred Spaces and Powerful Places In Tibetan Culture: A Collection of Essays, ed. Toni Huber. Dharamsala, H.P., India: The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1999, pp. 125–153. ISBN 81-86470-22-0.

- Namdak, Yondzin Lopön Tenzin. Masters of the Zhang Zhung Nyengyud: Pith Instructions from the Experiential Transmission of Bönpo Dzogchen, trans. & ed. C. Ermakova & D. Ermakov. New Delhi: Heritage Publishers, 2010.

- Norbu, Namkhai. 1995. Drung, Deu and Bön: Narrations, Symbolic languages and the Bön tradition in ancient Tibet. Translated from Tibetan into Italian edited and annotated by Adriano Clemente. Translated from Italian into English by Andrew Lukianowicz. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, Dharamsala, H.P., India. ISBN 81-85102-93-7.

- Pegg, Carole (2006). Inner Asia Religious Contexts: Folk-religious Practices, Shamanism, Tantric Buddhist Practices. Oxford University Press.

- Peters, Larry. Tibetan Shamanism: Ecstasy and Healing. Berkeley, Cal.: North Atlantic Books, 2016.

- Rossi, D. (1999). The philosophical view of the great perfection in the Tibetan Bon religion. Ithaca, New York: Snow Lion. The book gives translations of Bon scriptures "The Twelve Little Tantras" and "The View Which is Like the Lion's Roar".

- Samuel, Geoffrey (1993). Civilized Shamans. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070928062536/http://www.sharpham-trust.org/centre/Tibetan_unit_01.pdf (accessed: Thursday January 18, 2007)

- Yongdzin Lopön Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche (2012). Heart Essence of the Khandro. Heritage Publishers.

- Ghulam Hassan Lobsang, Skardu Baltistan, Pakistan,1997. " History of Bon Philosophy " written in Urdu/Persian style. The book outlines religious and cultural changes within the Baltistan/Tibet/Ladakh region over past centuries and explores the impact of local belief systems on the lives of the region's inhabitants in the post-Islamic era.

External links

- Tibet's Bon (in صينية and Standard Tibetan)

- Bon Foundation

- Bon in Belarus and Ukraine (in إنگليزية)

- Yungdrung Bon UK

- Ligmincha Institute

- Gyalshen Institute

- Studies

- Siberian Bo and Tibetan Bon, studies by Dmitry Ermakov

- CS1 maint: others

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Pages with plain IPA

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة التبتية

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from July 2024

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with صينية-language sources (zh)

- Articles with Standard Tibetan-language sources (bo)

- Articles with إنگليزية-language sources (en)

- Bon

- Dzogchen lineages