انقراض الهولوسين

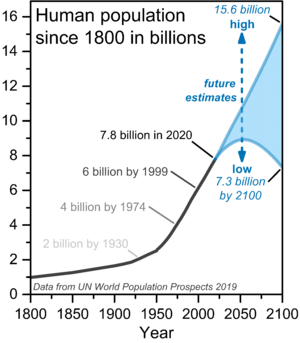

انقراض الهولوسين (Holocene extinction) أو انقراض العصر البشري (Anthropocene extinction)،[3][4] هو حدث انقراض بسبب البشر حدث خلال العصر الهولوسيني. شملت حالات الانقراض هذه العديد من فصائل النباتات[5][6][7] والحيوانات، بما في ذلك الثدييات، الطيور، الزواحف، البرمئيات، الأسماك، واللافقاريات، ولم يؤثر هذا على الأنواع الأرضية فحسب، بل أثر أيضاً على قطاعات كبيرة من الحياة البحرية.[8] مع التدهور واسع النطاق لبؤر التنوع الحيوي، مثل الشعاب المرجانية والغابات المطيرة، فضلاً عن مناطق أخرى، يُعتقد أن الغالبية العظمى من حالات الانقراض هذه غير موثقة، حيث لا تُكتشف الأنواع في وقت انقراضها، والذي لم يتم تسجيلها. ويقدر معدل انقراض الأنواع الحالي بما يتراوح بين 100-1000 مرة أعلى من معدلات الانقراض الأساسية الطبيعية[9][10][11][12][13] وهو في تزايد.[14] خلال 100-2-- سنة الماضية، تسارعت وتيرة فقدان التنوع الحيوي وانقراض الأنواع،[10] إلى الحد الذي جعل معظم علماء الحفظ الحيوي يعتقدون الآن أن النشاط البشري إما أنتج فترة من الانقراض الجماعي،[15][16] أو على وشك القيام بذلك.[17][18] وعلى هذا النحو، بعد الانقراضات الجماعية "الخمسة الكبرى"، أُشير إلى حدث انقراض العصر الهولوسيني أيضًا باسم الانقراض الجماعي السادس أو الانقراض السادس؛[19][20][21] نظرًا للاعتراف الأخير بالانقراض الكاپيتاني الجماعي، فقد أُقترح مصطلح الانقراض الجماعي السابع أيضاً لحدث انقراض الهولوسين.[22][23]

يأتي انقراض الهولوسين بعد انقراض معظم الحيوانات الضخمة خلال العصر البلايستوسيني المتأخر السابق. ومن المرجح أن بعض هذه الانقراضات كانت بسبب ضغط الصيد البشري.[24][25]

النظرية الأكثر شيوعاً هي أن الصيد الجائر للأنواع من قبل البشر أدى إلى زيادة ظروف الإجهاد الموجودة حيث تزامن انقراض الهولوسين مع استعمار البشر للعديد من المناطق الجديدة حول العالم. وعلى الرغم من وجود جدال حول مدى تأثير افتراس البشر وخسارة الموائل على انحدارهم، فقد ارتبط انخفاض بعض السكان بشكل مباشر ببداية النشاط البشري، مثل أحداث انقراض نيوزيلندا ومدغشقر وهاواي. وبصرف النظر عن البشر، ربما كان تغير المناخ عاملاً محركًا في انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة، وخاصة في نهاية العصر الپلایستوسيني.

على مدار العصر الهولوسيني المتأخر، كانت هناك المئات من حالات انقراض الطيور على الجزر عبر المحيط الهادي، بسبب الاستيطان البشري للجزر غير المأهولة سابقاً، وبلغت حالات الانقراض ذروتها حوالي عام 1300م.[26] لقد انقرض ما يقرب من 12% من أنواع الطيور بسبب النشاط البشري على مدى الـ 126.000 سنة الماضية، وهو ضعف التقديرات السابقة.[27]

في القرن العشرين، تضاعف عدد البشر أربع مرات، وزاد حجم الاقتصاد العالمي خمسة وعشرين ضعفاً.[28][29] لقد أدت هذه الحقبة من التسارع العظيم أو عصر الأنثروپوسين أو العصر البشري أيضًا إلى تسريع انقراض الأنواع.[30][31] من الناحية البيئية، أصبحت البشرية الآن "مفترساً عالمياً خارقاً" بشكل غير مسبوق،[32] التي تتغذى باستمرار على البالغين من الحيوانات المفترسة العليا الأخرى، وتستولي على الموائل الأساسية للأنواع الأخرى وتشردها،[33] ولها تأثيرات عالمية على شبكات الغذاء.[34] هناك العديد من الأمثلة الشهيرة للانقراضات داخل أفريقيا، آسيا، أوروپا، أستراليا، أمريكا الشمالية وأمريكا الجنوبية، وعلى الجزر الأصغر.

بشكل عام، يمكن ربط انقراض الهولوسين بالتأثير البشري على البيئة. يستمر انقراض الهولوسين حتى القرن 21، مع الاحتباس الحراري العالمي، تزايد تعداد البشر،[35][36][37][38] تزايد استهلاك الأفراد[10][39] (خاصة من قبل الأشخاص بالغي الثراء)،[40][41][42] وإنتاج واستهلاك اللحوم،[43][44][45][46][47][48] من بين أمور أخرى، كونها المحرك الرئيسي للانقراض الجماعي. إزالة الغابات،[43] الصيد الجائر للأسماك، احمضاض المحيطات، تدمير الأراضي الرطبة،[49] وانخفاض أعداد البرمائيات،[50] ومن بين أمور أخرى، هناك من بين الأمثلة الأوسع نطاقاً لفقدان التنوع الحيوي العالمي.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية

تتميز أحداث الانقراض الجماعية بفقدان ما لا يقل عن 75% من الأنواع خلال فترة جيولوجية قصيرة (أي أقل من 2 مليون سنة).[18][51] يُعرف انقراض الهولوسين أيضًا "بالانقراض السادس"، لأنه ربما يكون حدث الانقراض الجماعي السادس، بعد أحداث انقراض الأردوڤيشي-السيلوري، انقراض الديڤوني المتأخر، وانقراض الپرمي-الثلاثي، وانقراض الثلاثي-الجوراسي، وانقراض الطباشيري-الثلاثي.[52][53][54] إذا تم تضمين الانقراض الكاپيتاني الجماعي ضمن أحداث الانقراض الجماعية من الدرجة الأولى، فإن انقراض الهولوسين سيُعرف وفقًا لذلك "بالانقراض السابع".[22][23] الهولوسين هي الحقبة الجيولوجية الحالية.

نظرة عامة

لا يوجد اتفاق عام حول تاريخ بدء انقراض الهولوسين، أو انقراض العصر البشري، ونهاية حدث الانقراض الرباعي، والذي يتضمن تغير المناخ الذي أدى إلى نهاية العصر الجليدي الأخير، أو ما إذا كان ينبغي اعتبارهما حدثين منفصلين على الإطلاق.[55][56] ويرجع انقراض الهولوسين في المقام الأول إلى الأنشطة البشرية.[52][54][57] وقد زعم بعض المؤلفين أن أنشطة البشر القدماء الأوائل أدت أيضاً إلى أحداث الانقراض، على الرغم من أن الأدلة على ذلك غير قاطعة؛[58] ويُدعم ذلك من خلال الانقراض السريع للحيوانات الضخمة في أعقاب الاستعمار البشري الأخير في أستراليا، ونيوزيلندا، ومدغشقر.[53] في كثير من الحالات، يقترح أن حتى الضغط الضئيل للصيد كان كافياً للقضاء على حيوانات كبيرة، وخاصة في الجزر المنعزلة جغرافياً.[59][60] ولم تتعرض النباتات لخسائر كبيرة إلا خلال الفترات الأخيرة من الانقراض.[61]

معدل الانقراض

يقدر معدل انقراض الأنواع المعاصر بما يتراوح بين 100-1000 مرة أعلى من معدل الانقراض الأساسي، وهو المعدل النموذجي تاريخياً للانقراض (من حيث التطور الطبيعي للكوكب)؛[11][12][13][62] كما أن معدل الانقراض الحالي أعلى بمقدار 10-100 مرة من أي من الانقراضات الجماعية السابقة في تاريخ الأرض. ويقدر أحد العلماء أن معدل الانقراض الحالي قد يكون 10.000 مرة معدل الانقراض الأساسي، على الرغم من أن معظم العلماء يتوقعون معدل انقراض أقل بكثير من هذا التقدير الخارجي.[63] صرح عالم البيئة النظري ستوارت پيم أن معدل انقراض النباتات أعلى 100 مرة من المعدل الطبيعي.[64]

يزعم البعض أن الانقراض المعاصر لم يصل بعد إلى مستوى الانقراضات الجماعية الخمسة السابقة،[65] وأن هذه المقارنة تقلل من مدى خطورة الانقراضات الجماعية الخمسة الأولى.[66] يزعم جون بريگز أن البيانات غير كافية لتحديد المعدل الحقيقي للانقراضات، ويُظهِر أن تقديرات انقراض الأنواع الحالية تتفاوت بشكل كبير، حيث تتراوح من 1.5 نوع إلى 40.000 نوع تنقرض بسبب الأنشطة البشرية كل عام.[67] تشير كلتا الورقتين من بارنوسكي وآخرون. (2011) وهال وآخرون (2015) إلى أن المعدل الحقيقي للانقراض خلال الانقراضات الجماعية السابقة غير معروف، لأن بعض العضيات فقط تترك بقايا أحفورية، كما أن الدقة الزمنية للطبقة الأحفورية أكبر من الإطار الزمني لأحداث الانقراض.[18][68]

ومع ذلك، يتفق كل هؤلاء المؤلفين على وجود أزمة تنوع حيوي حديثة مع انخفاض أعداد الأنواع التي تؤثر على العديد من الأنواع، وأن انقراضاً جماعياً من صنع البشر في المستقبل يشكل خطراً كبيراً. وتؤكد الدراسة التي أجراها بارنوسكي وآخرون عام 2011 أن "معدلات الانقراض الحالية أعلى مما قد نتوقعه من السجل الأحفوري" وتضيف أن الضغوط البيئية البشرية، بما في ذلك تغير المناخ، وتجزؤ الموائل، والتلوث، والصيد الجائر، والصيد الجائر، والأنواع المجتاحة، وتوسع الكتلة الحيوية البشرية، سوف تكثف وتسرع معدلات الانقراض في المستقبل دون بذل جهود تخفيف كبيرة.[18]

في كتابه "مستقبل الحياة" (2002)، حسب إدوارد أوزبورن ولسون من جامعة هارڤرد أنه إذا استمر المعدل الحالي من التدمير البشري للغلاف الحيوي، فإن نصف أشكال الحياة العليا على الأرض سوف تنقرض بحلول عام 2100. ووجد استطلاع للرأي أجراه المتحف الأمريكي للتاريخ الطبيعي عام 1998 أن 70% من علماء الأحياء يعترفون بحدث انقراض مستمر من صنع البشر.[69]

في دراستين نُشرتا عام 2015، أدى الاستقراء من الانقراض الملحوظ لقواقع هاواي إلى استنتاج مفاده أن 7% من جميع الأنواع على الأرض ربما تكون قد انقرضت بالفعل.[70][71] توصلت دراسة أجريت عام 2021 ونشرت في دورية حدود الغابات والتغير العالمي إلى أن حوالي 3% فقط من سطح الأرض سليم بيئياً وحيوانياً، أي مناطق بها أعداد صحية من الأنواع الحيوانية الأصلية وبصمة بشرية قليلة أو معدومة.[72][73]

يشير تقرير التقييم العالمي للتنوع الحيوي وخدمات النظام البيئي لعام 2019، الذي نشرته المنصة الدولية لسياسات العلوم حول التنوع الحيوي وخدمات النظام البيئي التابعة للأمم المتحدة (IPBES)، إلى أنه من بين حوالي ثمانية ملايين نوع من النباتات والحيوانات، يواجه ما يقرب من مليون نوع خطر الانقراض في غضون عقود نتيجة لأفعال بشرية.[74][75][76] يتعرض الوجود البشري المنظم للخطر بسبب التدمير السريع والمتزايد للأنظمة التي تدعم الحياة على الأرض، وفقاً للتقرير، وهو نتيجة إحدى الدراسات الأكثر شمولاً لصحة الكوكب التي أجريت على الإطلاق.[77] علاوة على ذلك، يؤكد تقرير اقتصاديات التنوع الحيوي لعام 2021، الذي نشرته حكومة المملكة المتحدة، أن "التنوع الحيوي يتراجع بشكل أسرع من أي وقت مضى في تاريخ البشرية".[78][79] وفقًا لدراسة أجريت عام 2022 ونشرت في دورية حدود الغابات والتغير العالمي، فإن استطلاعاً شمل أكثر من 3.000 خبير يقول إن مدى الانقراض الجماعي قد يكون أكبر مما كان يُعتقد سابقاً، ويقدر أن ما يقرب من 30% من الأنواع "مهددة أو معرضة للانقراض عالمياً منذ عام 1500".[80][81] في تقرير صدر عام 2022، أدرجت IPBES الصيد غير المستدام والصيد الجائر وقطع الأشجار الجائر كبعض العوامل الرئيسية وراء أزمة الانقراض العالمية.[82] تشير دراسة أجريت عام 2022 ونشرت في ساينس أدڤنسز إلى أنه إذا وصل الاحترار العالمي إلى 2.7 درجة مئوية أو 4.4 درجة مئوية بحلول عام 2100، فإن 13% و27% من أنواع الفقاريات الأرضية سوف تنقرض بحلول ذلك الوقت، ويرجع ذلك إلى حد كبير إلى تغير المناخ (62%)، مع تحويل الأراضي من صنع البشر والانقراض المشترك الذي يمثل الباقي.[83][21][84] أظهرت دراسة أجريت عام 2023 ونشرت في PLOS One أن حوالي مليوني نوع مهددة بالانقراض، وهو ضعف التقدير الذي ورد في تقرير IPBES لعام 2019.[85] وفقًا لدراسة أجريت عام 2023 ونشرت في PNAS، انقرض 73 جنساً على الأقل من الحيوانات منذ عام 1500. وتقدر الدراسة أنه لو لم يكن البشر موجودين أبداً، لكان من الممكن أن يستغرق الأمر 18.000 سنة حتى تختفي نفس الأجناس بشكل طبيعي، مما دفع المؤلفين إلى استنتاج أن "معدلات الانقراض الحالية أعلى بنحو 35 مرة من المعدلات الأساسية المتوقعة السائدة في المليون سنة الماضية في غياب التأثيرات البشرية" وأن الحضارة البشرية تتسبب في "التشويه السريع لشجرة الحياة".[86][87][88]

السبب

—آن لاريگودري، السكرتيرة التنفيذية لمنظمة IPBES[89]

هناك إجماع واسع النطاق بين العلماء على أن النشاط البشري يسرع من انقراض العديد من الأنواع الحيوانية من خلال تدمير الموائل، واستهلاك الحيوانات كموارد، والقضاء على الأنواع التي ينظر إليها البشر على أنها تهديدات أو منافسين.[57] دفعت توجهات الانقراض المتزايدة التي تؤثر على العديد من مجموعات الحيوانات بما في ذلك الثدييات والطيور والزواحف والبرمائيات بعض العلماء إلى إعلان أزمة التنوع الحيوي.[90]

الجدل العلمي

كان وصف الانقراض الأخير بالانقراض الجماعي محل جدل بين العلماء. على سبيل المثال، يؤكد ستوارت پيم أن الانقراض الجماعي السادس "هو شيء لم يحدث بعد - نحن على وشك حدوث ذلك".[91] تشير العديد من الدراسات إلى أن الأرض دخلت في حدث الانقراض الجماعي السادس،[52][50][40][92] بما في ذلك بحث أجراه بارونسكي وزملائه عام 2015.[14] وفي نوفمبر 2017، أصدر علماء العالم بياناً بعنوان "تحذير علماء العالم للإنسانية: الإشعار الثاني"، بقيادة ثمانية مؤلفين ووقع عليه 15.364 عالماً من 184 بلد، وأكد البيان، من بين أمور أخرى، أننا "أطلقنا اسم حدث الانقراض الجماعي، السادس في حوالي 540 مليون عام، حيث يمكن القضاء على العديد من أشكال الحياة الحالية أو على الأقل انتهائها بحلول نهاية هذا القرن".[43] أفاد تقرير الكوكب الحي لعام 2020 الصادر عن الصندوق العالمي للطبيعة أن الحياة البرية انخفضت بنسبة 68% منذ عام 1970 نتيجة للإفراط في الاستهلاك، والنمو السكاني، والزراعة المكثفة، وهو دليل آخر على أن البشر أطلقوا العنان لحدث الانقراض الجماعي السادس؛ ومع ذلك، فقد تم التشكيك في هذا الاكتشاف من خلال دراسة أجريت عام 2020، والتي افترضت أن هذا الانخفاض الكبير كان مدفوعاً في المقام الأول بعدد قليل من السكان المتطرفين، وأنه عند إزالة هؤلاء المتطرفين، يتحول الاتجاه إلى انخفاض بين الثمانينيات وع. 2000، لكن إلى اتجاه إيجابي تقريباً بعد عام 2000.[93][94][95][96] ويقول تقرير نشرته دورية الحدود في علم الحفاظ عام 2021، والذي يستشهد بالدراستين المذكورتين، إن "أحجام أعداد الفقاريات التي رُصدت عبر السنين انخفضت بمعدل 68% على مدى العقود الخمسة الماضية، مع وجود مجموعات سكانية معينة في انخفاض شديد، وبالتالي ينذر بالانقراض الوشيك لأنواعها"، ويؤكد أن "أننا بالفعل على طريق الانقراض السادس الكبير أصبح الآن لا يمكن إنكاره علمياً".[97] تستند مقالة مراجعة نشرتها دورية بيولوجيكال رڤيوز في يناير 2022 في إلى دراسات سابقة وثقت تراجع التنوع الحيوي لتؤكد أن حدث الانقراض الجماعي السادس الناجم عن النشاط البشري جاري حالياً.[20][98] أفادت دراسة نشرتها ساينس أدڤنسز في ديسمبر 2022 أن "الكوكب دخل مرحلة الانقراض الجماعي السادس" وحذرت من أن التوجهات البشرية الحالية، وخاصة فيما يتعلق بالمناخ وتغيرات استخدام الأراضي، قد تؤدي إلى فقدان أكثر من عُشر الأنواع النباتية والحيوانية بحلول نهاية القرن.[99][100] وأن 12% من جميع أنواع الطيور مهددة بالانقراض.[101] وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2023 نشرتها بيولوجيكال رڤيوز أن من بين 70.000 نوع تمت مراقبتها، يعاني حوالي 48% منها من انخفاض في أعدادها بسبب الضغوط البشرية، في حين أن 3% فقط لديها أعداد متزايدة.[102][103][104]

وفقًا لتقرير التنمية البشرية لعام 2020 الصادر عن برنامج الأمم المتحدة الإنمائي بعنوان الحدود التالية: التنمية البشرية والعصر البشري:

إن التنوع الحيوي على كوكب الأرض يتراجع، حيث يواجه ربع الأنواع خطر الانقراض، والعديد منها في غضون عقود. ويعتقد العديد من الخبراء أننا نعيش في، أو على وشك، انقراض جماعي للأنواع، وهو السادس في تاريخ الكوكب والأول الذي تسببت فيه عضية واحدة-نحن.[105]

وجد تقرير الكوكب الحي لعام 2022 أن أعداد الفقاريات البرية انخفضت بمعدل متوسط يبلغ حوالي 70% منذ عام 1970، حيث كانت الزراعة وصيد الأسماك المحركين الرئيسيين لهذا الانخفاض.[106][107]

يزعم بعض العلماء، ومنهم رودولفو ديرزو وپل إهرليتش، أن الانقراض الجماعي السادس غير معروف إلى حد كبير لمعظم الناس على مستوى العالم، كما يسيء فهمه كثيرون في المجتمع العلمي. ويقولون إن اختفاء الأنواع، الذي يحظى بأكبر قدر من الاهتمام، ليس هو جوهر الأزمة، بل "التهديد الوجودي المتمثل في انقراض أعداد لا حصر لها من السكان".[108]

العصر البشري

إن وفرة انقراضات الأنواع التي تعتبر النشاط البشري، كانت تسمى أحياناً (خاصة عند الإشارة إلى أحداث مستقبلية مفترضة) بشكل جماعي "انقراض العصر البشري".[57][109][110] العصر البشري هو مصطلح طُرح عام 2000.[111][112] يفترض البعض الآن أن نطاقاً جيولوجياً جديداً قد بدأ، مع الانقراض الأكثر مفاجأة وانتشاراً للأنواع منذ انقراض العصر البشري-الپاليوجيني قبل 66 مليون سنة.[53]

يُستخدم مصطلح "العصر البشري" بشكل متكرر من قبل العلماء، وقد يشير بعض المعلقين إلى الانقراضات الحالية والمستقبلية المتوقعة كجزء من انقراض الهولوسين الأطول.[113][114] إن الحدود بين الهولوسين والعصر البشري محل نزاع، حيث يؤكد بعض المعلقين على وجود تأثير بشري كبير على المناخ في معظم ما يُعتبر عادةً نطاق الهولوسين.[115] يرى بعض الخبراء أن الانتقال من الهولوسين إلى العصر البشري كان في بداية الثورة الصناعية. كما لاحظوا أن الاستخدام الرسمي لهذا المصطلح في المستقبل القريب سوف يعتمد بشكل كبير على فائدته، وخاصة بالنسبة لعلماء الأرض الذين يدرسون فترات الهولوسين المتأخرة.

وقد اقترح أن النشاط البشري جعل الفترة التي بدأت من منتصف القرن العشرين مختلفة بما يكفي عن بقية الهولوسين لاعتبارها نطاقاً زمنياً جديداً، يُعرف باسم العصر البشري،[116][117] مصطلح نظرت المفوضية الدولية لعلم طبقات الأرض عام 2016 في إدراجه ضمن الجدول الزمني لتاريخ الأرض، ولكن الاقتراح رُفض عام 2024.[118][119][120] ولتحديد الهولوسين باعتباره حدث انقراض، يتعين على العلماء أن يحددوا بالضبط متى بدأت انبعاثات غاز الدفيئة الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية في تغيير مستويات الغلاف الجوي الطبيعية على نطاق عالمي بشكل يمكن قياسه، ومتى تسببت هذه التغيرات في حدوث تغييرات في المناخ العالمي. وباستخدام عاملين كيميائيين من نوى الجليد في أنتاركتيكا، قدر الباحثون تقلبات غازات ثاني أكسيد الكربون (CO2) والميثان (CH4) في الغلاف الجوي للأرض خلال الپلایستوسين المتأخر والهولوسين.[115] وتشير تقديرات تقلبات هذين الغازين في الغلاف الجوي، باستخدام عاملين كيميائيين من نوى الجليد في أنتاركتيكا، بشكل عام إلى أن ذروة العصر البشري حدثت خلال القرنين الماضيين: بدءاً من الثورة الصناعية، عند تسجيل أعلى مستويات لغازات الدفيئة.[121][122]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

علم البيئة البشري

أشار مقال نشرته مجلة ساينس عام 2015 إلى أن البشر فريدون من نوعهم في علم البيئة باعتبارهم "مفترساً عالمياً فائقاً" غير مسبوق، حيث يفترسون بانتظام أعداداً كبيرة من المفترسات العليا البرية والبحرية البالغة، ولديهم قدر كبير من التأثير على شبكات الغذاء والأنظمة المناخية في جميع أنحاء العالم.[32] على الرغم من وجود نقاش كبير حول مدى مساهمة الافتراس البشري والتأثيرات غير المباشرة في الانقراضات التي حدثت في عصور ما قبل التاريخ، فقد ارتبطت بعض حالات انهيار أعداد الحيوانات ارتباطاً مباشراً بوصول البشر.[24][53][56][57] كان النشاط البشري هو السبب الرئيسي لانقراض الثدييات منذ العصر الپلایستوسيني المتأخر.[90] وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2018 ونشرت في PNAS أن الكتلة الحيوية للثدييات البرية انخفضت بنسبة 83% منذ فجر الحضارة البشرية. وبلغ انخفاض الكتلة الحيوية 80% للثدييات البحرية، و50% للنباتات، و15% للأسماك. وتشكل الماشية حاليًا 60% من الكتلة الحيوية لجميع الثدييات على الأرض، تليها البشر (36%) والثدييات البرية (4%). أما بالنسبة للطيور، فإن 70% منها مستأنسة، مثل الدواجن، في حين أن 30% فقط برية.[123][124]

الانقراض التاريخي

الأنشطة البشرية

أنشطة ساهمت في الانقراضات

ربما يعود تاريخ انقراض الحيوانات والنباتات والعضيات الأخرى الناجم عن النشاط البشري إلى أواخر الپلایستوسين، أي منذ أكثر من 12.000 سنة مضت..[57] وهناك علاقة بين انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة ووصول البشر.[125][126][127] كما عانت الحيوانات الضخمة التي لا تزال موجودة من انخفاضات حادة كانت مرتبطة ارتباطاً وثيقاً بالتوسع والنشاط البشري.[128] على مدار 125.000 سنة الماضية، انخفض متوسط حجم جسم الحيوانات البرية بنسبة 14% نتيجة للأنشطة البشرية في عصور ما قبل التاريخ التي أدت إلى القضاء على الحيوانات الضخمة في جميع القارات باستثناء أفريقيا.[129]

تأسست الحضارة الإنسانية على الزراعة ونمت منها.[130] كلما زادت الأراضي المستخدمة للزراعة، زاد عدد السكان الذين تستطيع الحضارة إعاشتهم،[115][130] وقد أدى انتشار الزراعة لاحقاً إلى تحويل واسع النطاق للموائل.[10]

يعتبر تدمير البشر للموائل، وبالتالي استبدال النظم البيئية المحلية الأصلية، أحد الأسباب الرئيسية للانقراض.[131] إن التحويل المستمر للغابات والأراضي الرطبة الغنية بالتنوع الحيوي إلى حقول ومراعي أفقر (ذات قدرة استيعابية أقل للأنواع البرية)، على مدى العشرة آلاف عام الماضية، أدى إلى تقليص قدرة الأرض على استيعاب الطيور البرية والثدييات، من بين العضيات الأخرى، بشكل كبير، سواء من حيث حجم السكان أو عدد الأنواع.[132][133][134]

تشمل الأسباب البشرية الأخرى المرتبطة بحدث الانقراض إزالة الغابات والصيد والتلوث،[135] إدخال أنواع غير محلية في مناطق مختلفة، وانتشار الأمراض المعدية وانتقالها من خلال الماشية والمحاصيل.[62]

الزراعة وتغير المناخ

إن التحقيقات الأخيرة في ممارسة حرق المناظر الطبيعية خلال ثورة العصر الحجري الحديث لها تأثير كبير على المناقشة الحالية حول توقيت العصر البشري والدور الذي ربما لعبه البشر في إنتاج غازات الدفيئة قبل الثورة الصناعية.[130] تثير الدراسات التي أجريت على الصيادين وجامعي الثمار الأوائل تساؤلات حول الاستخدام الحالي لحجم السكان أو كثافتهم كمؤشر على كمية إزالة الأراضي والحرق البشري الذي حدث في أوقات ما قبل الصناعة.[136][137] وقد تساءل العلماء عن العلاقة بين حجم السكان والتغيرات الإقليمية المبكرة.[137] في ورقة بحثية أجراها روديمان وإليس عام 2009، زعم روديمان وإليس أن المزارعين الأوائل الذين شاركوا في أنظمة الزراعة استخدموا مساحة أكبر للفرد مقارنة بالمزارعين في وقت لاحق من الهولوسين، الذين كثفوا عملهم لإنتاج المزيد من الغذاء لكل وحدة مساحة (وبالتالي، لكل عامل)؛ وزعموا أن المشاركة الزراعية في إنتاج الأرز التي نفذت منذ آلاف السنين من قبل سكان صغيرين نسبيًا خلقت تأثيرات بيئية كبيرة من خلال وسائل واسعة النطاق لإزالة الغابات.[130]

في حين أن هناك عدداً من العوامل البشرية المعترف بها باعتبارها تساهم في ارتفاع تركيزات الميثان وثاني أكسيد الكربون في الغلاف الجوي، فإن ممارسات إزالة الغابات والتطهير الإقليمي المرتبطة بالتنمية الزراعية ربما ساهمت بشكل أكبر في هذه التركيزات على مستوى العالم خلال آلاف السنين السابقة.[121][130][138] يزعم العلماء الذين يستخدمون مجموعة متنوعة من البيانات الأثرية والبيئية القديمة أن العمليات التي ساهمت في التعديل البشري الكبير للبيئة امتدت لآلاف السنين على نطاق عالمي وبالتالي، لم تنشأ في وقت متأخر مثل الثورة الصناعية. زعم عالم المناخ القديم وليام روديمان أنه في أوائل الهولوسين قبل 11.000 سنة، كانت مستويات ثاني أكسيد الكربون والميثان في الغلاف الجوي تتقلب في نمط مختلف عن الپلایستوسين الذي سبقه.[115][136][138] وزعم أن أنماط الانخفاض الكبير في مستويات ثاني أكسيد الكربون خلال العصر الجليدي الأخير من الپلایستوسين ترتبط عكسياً بالهولوسين حيث كانت هناك زيادات هائلة في مستويات ثاني أكسيد الكربون منذ حوالي 8.000 سنة ومستويات الميثان بعد ذلك بنحو 3.000 سنة.[138] يشير الارتباط بين انخفاض ثاني أكسيد الكربون في العصر الالپلایستوسيني وزيادته خلال العصر الهولوسيني إلى أن سبب شرارة غازات الدفيئة في الغلاف الجوي كان نمو الزراعة البشرية خلال العصر الهولوسيني.[115][138]

تغير المناخ

أحد النظريات الرئيسية التي تفسر الانقراضات المبكرة في العصر الهولوسيني هو تغير المناخ التاريخي. اقترحت نظرية تغير المناخ أن تغير المناخ بالقرب من نهاية العصر البلايستوسيني المتأخر أدى إلى إجهاد الحيوانات الضخمة إلى حد الانقراض.[113][140] يعتقد بعض العلماء أن تغير المناخ المفاجئ هو المحفز لانقراض الحيوانات الضخمة في نهاية العصر البلايستوسيني، ويعتقد معظمهم أن زيادة الصيد من قبل البشر في العصر الحديث المبكر لعبت أيضاً دوراً، بينما اقترح آخرون أن الاثنين تفاعلا معاً.[53][141][142] في الأمريكتين، تم تقديم تفسير مثير للجدل للتحول في المناخ تحت فرضية تأثير يونگر درياس، والتي تنص على أن تأثير المذنبات أدى إلى تبريد درجات الحرارة العالمية.[143][144] وعلى الرغم من شعبيتها بين غير العلماء، فإن هذه الفرضية لم يقبلها أبداً الخبراء ذوي الصلة، الذين رفضوها باعتبارها نظرية هامشية.[145]

الانقراض المعاصر

التاريخ

يعتبر الانفجار السكاني البشري المعاصر[33][147] والنمو السكاني المستمر، إلى جانب نمو الاستهلاك الفردي، بشكل بارز في القرنين الماضيين، على أنها الأسباب الأساسية للانقراض.[10][14][40][39][97] صرحت إنگر أندرسن، المديرة التنفيذية لبرنامج الأمم المتحدة للبيئة، قائلة: "إننا بحاجة إلى أن نفهم أنه كلما زاد عدد البشر، زاد الضغط الذي نفرضه على الأرض. وفيما يتعلق بالتنوع الحيوي، فإننا في حالة حرب مع الطبيعة".[148]

ويؤكد بعض العلماء أن ظهور الرأسمالية كنظام اقتصادي مهيمن أدى إلى تسريع الاستغلال والتدمير البيئي،[149][150][41][151] وقد أدى أيضاً إلى تفاقم الانقراض الجماعي للأنواع.[152] على سبيل المثال، يفترض ديڤد هارڤي، الأستاذ في جامعة مدينة نيويورك أن عصر الليبرالية الجديدة "يصادف أنه عصر الانقراض الجماعي الأسرع للأنواع في تاريخ الأرض الحديث".[153] ويخلص عالم البيئة وليام ريس إلى أن "النموذج الليبرالي الجديد يساهم بشكل كبير في تفكك الكوكب" من خلال التعامل مع الاقتصاد والمجال البيئي كنظامين منفصلين تماماً، وإهمال الأخير.[154] كانت منظمات الضغط الرئيسية التي تمثل الشركات في صناعات الزراعة ومصائد الأسماك والغابات والورق والتعدين والنفط والغاز، بما في ذلك غرفة التجارة الأمريكية، تقاوم التشريعات التي قد تعالج أزمة الانقراض. وذكر تقرير صادر عام 2022 عن مؤسسة إنفلونس ماپ البحثية المعنية بالمناخ أنه "على الرغم من أن جمعيات الصناعة، وخاصة في الولايات المتحدة، تبدو مترددة في مناقشة أزمة التنوع الحيوي، إلا أنها منخرطة بوضوح في مجموعة واسعة من السياسات ذات التأثيرات الكبيرة على فقدان التنوع الحيوي".[155]

إن فقدان الأنواع الحيوانية من المجتمعات البيئية، فناءها، يرجع في المقام الأول إلى النشاط البشري.[52] وقد أدى هذا إلى غابات فارغة، ومجتمعات بيئية خالية من الفقاريات الكبيرة.[57][157] لا ينبغي الخلط بين هذا والانقراض، لأنه يشمل اختفاء الأنواع وانخفاض الوفرة.[158] أُشير إلى تأثيرات الفناء لأول مرة في ندوة التفاعلات النباتاية-الحيوانية في جامعة كامپيناس بالبرازيل عام 1988 في سياق الغابات الاستوائية الجديدة.[159] ومنذ ذلك الحين، اكتسب المصطلح استخداماً أوسع في علم الحفاظ الحيوي باعتباره ظاهرة عالمية.[52][159]

انخفضت أعداد القطط الكبيرة بشكل حاد على مدار نصف القرن الماضي وقد تواجه الانقراض في العقود التالية. وفقًا لتقديرات الاتحاد العالمي للحفاظ على الطبيعة عام 2011: انخفض عدد الأسود من 450.000 إلى 25.000؛ وانخفض عدد الفهود من 750.000 إلى 50.000؛ وانخفض عدد الفهود الصيادة (الشيتا) من 45.000 إلى 12.000؛ وانخفض عدد النمور من 50.000 إلى 3.000 في البرية.[160] أظهرت دراسة أجريت في ديسمبر 2016 من قبل جمعية علم الحيوان في لندن، وشركة پانثرا، وجمعية الحفاظ على الحياة البرية، أن الفهود الصيادة أقرب إلى الانقراض مما كان يُعتقد في السابق، حيث بقي منها 7.100 فقط في البرية، وهم موجودون ضمن 9% فقط من نطاقهم التاريخي.[161] الضغوط البشرية هي المسؤولة عن انهيار أعداد الفهود الصيادة، بما في ذلك فقدان الفرائس بسبب الصيد الجائر من قبل البشر، والقتل الانتقامي من قبل المزارعين، وفقدان الموائل، والتجارة غير المشروعة في الحياة البرية.[162] شهدت أعداد الدببة البنية انخفاضاً مماثلاً في أعدادها.[163]

يشير مصطلح تراجع الملقحات إلى الانخفاض في وفرة الحشرات والملقحات الحيوانية الأخرى في العديد من النظم البيئية في جميع أنحاء العالم بدءاً من نهاية القرن العشرين، واستمراراً حتى يومنا هذا.[164] الملقحات، التي تعد ضرورية لـ 75% من المحاصيل الغذائية، تتراجع على مستوى العالم من حيث الوفرة والتنوع.[165]

أشارت دراسة أجريت عام 2017 بقيادة هانز دي كرون من جامعة رادبود إلى أن الكتلة الحيوية للحياة الحشرية في ألمانيا انخفضت بمقدار ثلاثة أرباع في السنوات الخمس والعشرين السابقة. وذكر الباحث المشارك ديڤ جولسون من جامعة سسكس أن دراستهم تشير إلى أن البشر يجعلون أجزاء كبيرة من الكوكب غير صالحة للسكنى بالنسبة للحياة البرية. ووصف جولسون الوضع بأنه "كارثة بيئية تقترب"، مضيفاً أنه "إذا فقدنا الحشرات، فسوف ينهار كل شيء".[166] وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2019 أن أكثر من 40% من أنواع الحشرات مهددة بالانقراض.[167] إن أهم العوامل المؤثرة في انخفاض أعداد الحشرات مرتبطة بممارسات الزراعة المكثفة، إلى جانب استخدام المبيدات الحشرية وتغير المناخ.[168] ينخفض عدد الحشرات في العالم بنحو 1-2% سنوياً.[169]

لقد دفعنا معدل الانقراض الحيوي، والخسارة الدائمة للأنواع، إلى الارتفاع عدة مئات من المرات فوق مستوياته التاريخية، ونحن مهددون بفقدان غالبية جميع الأنواع بحلول نهاية القرن 21.

— پيتر ريڤن، الرئيس السابق للجمعية الأمريكية لتقدم العلوم، في مقدمة منشور أطلس الجمعية الأمريكية لتقدم العلوم للسكان والبيئة[171]

من المتوقع أن تنقرض أنواع مختلفة من العضيات في المستقبل القريب،[174] ومن بيهما بعض من أنواع وحيد القرن،[175][176] الرئيسيات،[146] and pangolins.[177] وأنواع أخرى، بما في ذلك العديد من أنواع الزرافات، "أنواعاً مهددة بخطر انقراض أدنى" وتشهد انخفاضاً كبيراً في أعدادها بسبب التأثيرات البشرية بما في ذلك الصيد وإزالة الغابات والصراعات.[178][179] الصيد وحده يهدد أعداد الطيور والثدييات في جميع أنحاء العالم.[180][181][182]

إن القتل المباشر للحيوانات الضخمة من أجل لحومها وأجزاء أجسامها هو المحرك الرئيسي لتدميرها، حيث انخفض عدد أنواع الحيوانات الضخمة البالغ عددها 362 بنسبة 70% اعتباراً من عام 2019.[183][184] عانت الثدييات على وجه الخصوص من خسائر فادحة نتيجة للنشاط البشري (خاصة خلال حدث الانقراض الرباعي، لكن جزئياً خلال العصر الهولوسيني) وقد يستغرق الأمر عدة ملايين من السنين حتى تتعافى.[185][186]

اكتشفت التقييمات المعاصرة أن ما يقرب من 41% من البرمائيات، و25% من الثدييات، و21% من الزواحف، و14% من الطيور مهددة بالانقراض، وهو ما قد يؤدي إلى تعطيل النظم البيئية على نطاق عالمي والقضاء على مليارات السنين من التنوع التطوري.[187][188] التزمت الـ 189 بلد الموقعة على اتفاقية التنوع الحيوي (اتفاقية ريو)،[189] بإعداد خطة عمل للتنوع الحيوي، وهي خطوة أولى نحو تحديد الأنواع المهددة بالانقراض والموائل المحددة، بلداً ببلد[needs update].[190]

للمرة الأولى منذ انقراض الديناصورات قبل 65 مليون سنة، نواجه انقراضاً جماعياً عالمياً للحياة البرية. ونتجاهل تراجع الأنواع الأخرى على حسابنا ــ فهي المقياس الذي يكشف عن تأثيرنا على العالم الذي يدعمنا.

— مايك باريت، مدير العلوم والسياسات في فرع الصندوق العالمي للحياة البرية بالمملكة المتحدة[191]

وخلصت دراسة أجريت عام 2023 ونشرت في مجلة كرنت بيولوجي إلى أن معدلات فقدان التنوع الحيوي الحالية قد تصل إلى نقطة تحول وتؤدي حتما إلى انهيار النظام البيئي بالكامل.[192]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الانقراضات الحديثة

قد تُعزى الانقراضات الحديثة بشكل مباشر إلى التأثيرات البشرية، في حين يمكن أن تُعزى الانقراضات التي حدثت في عصور ما قبل التاريخ إلى عوامل أخرى.[52][14]

يصف الاتحاد العالمي للحفاظ على الطبيعة الانقراضات "الحديثة" بأنها تلك التي حدثت بعد نقطة القطع 1500،[193] وقد انقرضت منذ ذلك الوقت وحتى عام 2009 ما لا يقل عن 875 نوعاً من النباتات والحيوانات.[194] بعض الأنواع، مثل أيل الأب داڤيد[195] وغراب هاواي،[196] انقرضت في البرية، ولا توجد على قيد الحياة إلا في مجموعات بالأسر. أما المجموعات الأخرى فهي منقرضة محلياً فقط (مُبادة)، ولا تزال موجودة في أماكن أخرى، لكن انتشارها انخفض،[197] كما حدث مع انقراض الحيتان الرمادية في الأطلسي،[198] ومن السلحفاة البحرية جلدية الظهر في ماليزيا.[199]

منذ أواخر العصر الپلستوسيني، كان البشر (مع عوامل أخرى) يدفعون بسرعة أكبر الفقاريات نحو الانقراض، وفي هذه العملية يقاطعون سمة من سمات النظم البيئية عمرها 66 مليون عام، وهي العلاقة بين النظام الغذائي وكتلة الجسم، والتي يقترح الباحثون أنها قد تكون لها عواقب غير متوقعة.[200][201] وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2019 ونشرت في ناتشر كومينيكيشنز أن فقدان التنوع الحيوي السريع يؤثر على الثدييات والطيور الأكبر حجماً بدرجة أكبر بكثير من الثدييات والطيور الأصغر حجماً، حيث من المتوقع أن تتقلص كتلة جسم هذه الحيوانات بنسبة 25% خلال القرن المقبل. ووجدت دراسة أخرى أجريت عام 2019 ونشرت في بيولوجي لترز أن معدلات الانقراض ربما تكون أعلى بكثير من التقديرات السابقة، وخاصة بالنسبة لأنواع الطيور.[202]

يسرد تقرير التقييم العالمي للتنوع الحيوي وخدمات النظم البيئية لعام 2019 الأسباب الرئيسية للانقراضات المعاصرة بترتيب تنازلي: (1) التغيرات في استخدام الأراضي والبحر (في المقام الأول الزراعة والصيد الجائر على التوالي)؛ (2) الاستغلال المباشر للعضيات مثل الصيد؛ (3) تغير المناخ الناجم عن أنشطة الإنسان؛ (4) التلوث و(5) الأنواع الغريبة المجتاحة المنتشرة عن طريق التجارة البشرية. ويتوقع هذا التقرير، إلى جانب تقرير الكوكب الحي لعام 2020 الصادر عن الصندوق العالمي للحياة البرية، أن يكون تغير المناخ هو السبب الرئيسي في العقود القليلة القادمة.[39] هذا التقرير، إلى جانب تقرير الكوكب الحي لعام 2020 الصادر عن الصندوق العالمي للطبيعة، يتوقعان أن يكون تغير المناخ هو السبب الرئيسي في العقود القليلة القادمة.[39][95]

تشير دراسة نُشرت في PNAS في يونيو 2020 إلى أن أزمة الانقراض المعاصرة "قد تكون التهديد البيئي الأكثر خطورة لاستمرار الحضارة، لأنها لا رجعة فيها" وأن تسارعها "مؤكد بسبب النمو السريع في أعداد البشر ومعدلات الاستهلاك". ووجدت الدراسة أن أكثر من 500 نوع من الفقاريات على وشك الانقراض في العقدين المقبلين.[92]

تدمير الموئل

الكتلة الحيوية للثدييات على وجه الأرض في 2018[123][124]

يقوم البشر بزراعة أصناف المحاصيل وتربية الحيوانات المستأنسة وتدميرها على حد سواء. وقد أدى التقدم في النقل والزراعة الصناعية إلى زراعة المحصول الواحد وانقراض العديد من الأصناف. كما أدى استخدام بعض النباتات والحيوانات كغذاء إلى انقراضها، بما في ذلك السيلفيوم والحمام الزاجل.[203] عام 2012، قُدِّر أن 13% من مساحة الأرض الخالية من الجليد تُستخدم كمواقع زراعية للمحاصيل الصفراء، و26% تُستخدم كمراعي، و4% مناطق صناعية-حضرية.[204]

في مارس 2019، نشرت ناتشر كليمات تشانج دراسة أجراها علماء بيئة من جامعة يل، وجدوا فيها أن استخدام البشر للأراضي على مدى نصف القرن المقبل سيؤدي إلى تقليص موائل 1700 نوع بنسبة تصل إلى 50%، مما يدفعها إلى الاقتراب من الانقراض.[205][206] وفي الشهر نفسه، نشرت PLOS Biology دراسة مماثلة مستندة إلى العمل في جامعة كوينزلاند، والتي وجدت أن "أكثر من 1200 نوع على مستوى العالم تواجه تهديدات لبقائها في أكثر من 90% من موئلها، ومن المؤكد أنها ستواجه الانقراض في حالة عدم تدخل الجهات المعنية بالحفاظ على البيئة".[207][208]

منذ عام 1970، انخفضت أعداد أسماك المياه العذبة المهاجرة بنسبة 76%، وفقًا لبحث نشرته جمعية علم الحيوان في لندن في يوليو 2020. بشكل عام، يتعرض حوالي واحد من كل ثلاثة أنواع من أسماك المياه العذبة للخطر بسبب تدهور الموائل الناجم عن البشر والصيد الجائر.[209]

يزعم بعض العلماء والأكاديميين أن الزراعة الصناعية والطلب المتزايد على اللحوم يساهم في فقدان التنوع الحيوي العالمي بشكل كبير حيث أن هذا هو المحرك الرئيسي لإزالة الغابات وتدمير الموائل؛ الموائل الغنية بالأنواع، مثل منطقة الأمازون وإندونيسيا[211][212] تحولت لأراضي زراعية.[54][213][46][214][215] توصلت دراسة أجراها الصندوق العالمي للحياة البرية عام 2017 إلى أن 60% من فقدان التنوع الحيوي يمكن أن يعزى إلى النطاق الواسع لزراعة المحاصيل العلفية المطلوبة لتربية عشرات البلايين من الحيوانات في المزارع.[47] علاوة على ذلك، وجد تقرير أصدرته منظمة الأغذية والزراعة التابعة للأمم المتحدة عام 2006، تحت عنوان الظل الطويل للثروة الحيوانية، أن قطاع الثروة الحيوانية هو "لاعب رئيسي" في فقدان التنوع الحيوي.[216]

في الآونة الأخيرة، عام 2019، عزا تقرير التقييم العالمي للتنوع الحيوي وخدمات النظم البيئية الصادر عن المنتدى الحكومي الدولي للعلوم والسياسات في مجال التنوع الحيوي وخدمات النظم الحيوية الكثير من هذا الدمار البيئي إلى الزراعة وصيد الأسماك، حيث كان لصناعات اللحوم والألبان تأثير كبير للغاية.[44] منذ السبعينيات، ارتفعت إنتاجية الغذاء بشكل كبير لإطعام عدد متزايد من السكان وتعزيز النمو الاقتصادي، ولكن بثمن باهظ على البيئة والأنواع الأخرى. ويقول التقرير إن نحو 25% من أراضي الأرض الخالية من الجليد تُستخدم لرعي الماشية.[77] حذرت دراسة أجريت عام 2020 ونشرت في ناتشر كوميونيكشنز من أن التأثيرات البشرية الناجمة عن الإسكان والزراعة الصناعية وخاصة استهلاك اللحوم تمحو ما مجموعه 50 بليون سنة من تاريخ تطور الأرض (المعرفة بالتنوع التطوري)[أ]) والتسبب في انقراض بعض "أكثر الحيوانات تفرداً على هذا الكوكب"، من بينها ليمور آي آي، وسحلية التمساح الصينية، وآكل النمل الحرشفي.[217][218] وصرح المؤلف الرئيسي للدراسة ريكي گمبز:

نعلم من جميع البيانات المتوفرة لدينا عن الأنواع المهددة بالانقراض أن التهديدات الأكبر تتمثل في التوسع الزراعي والطلب العالمي على اللحوم. إن المراعي وإزالة الغابات المطيرة لإنتاج فول الصويا، في نظري، هي أكبر العوامل الدافعة وراء ذلك – والاستهلاك المباشر للحيوانات.[217]

كما تم الاستشهاد بالتحضر باعتباره أحد العوامل الرئيسية وراء فقدان التنوع الحيوي، وخاصة الحياة النباتية. فقد وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 1999 حول استئصال النباتات المحلية في بريطانيا العظمى أن التحضر ساهم على الأقل بنفس القدر في انقراض النباتات المحلية مثل الزراعة.[219]

تغير المناخ

من المتوقع أن يكون تغير المناخ أحد الأسباب الرئيسية لخطر الانقراض الناجم عن تغير المناخ في القرن 21.[39] تؤدي مستويات ثاني أكسيد الكربون المتزايدة إلى تدفق هذا الغاز إلى المحيط، مما يزيد من حموضته. تتعرض العضيات البحرية التي تمتلك أصدافاً من كربونات الكالسيوم أو هياكل خارجية لضغوط فسيولوجية عندما يتفاعل الكربونات مع الحمض. على سبيل المثال، يؤدي هذا بالفعل إلى تببيض العديد من الشعاب المرجانية في جميع أنحاء العالم، والتي توفر موئلاً قيماً وتحافظ على التنوع الحيوي المرتفع.[221] تتأثر أيضًا البطن قدميات البحرية، وذوات المصراعين، واللافقاريات الأخرى، وكذلك العضيات التي تتغذى عليها.[222][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] وأشارت بعض الدراسات إلى أن تغير المناخ ليس هو السبب وراء أزمة الانقراض الحالية، بل متطلبات الحضارة الإنسانية المعاصرة على الطبيعة.[223][224] ومع ذلك، من المتوقع أن يؤدي ارتفاع متوسط درجات الحرارة العالمية بما يزيد عن 5.2 درجة مئوية إلى انقراض جماعي مماثل لأحداث الانقراض الجماعي "الخمسة الكبرى" في دهر الحياة الظاهرة، حتى بدون تأثيرات بشرية أخرى على التنوع الحيوي.[225]

الاستغلال المفرط

قد يؤدي إن الإفراط في الصيد إلى انخفاض أعداد الطرائد بأكثر من النصف، فضلاً عن انخفاض كثافة الحيوانات، وقد يؤدي إلى انقراض بعض الأنواع.[228] الحيوانات التي تعيش بالقرب من القرى معرضون بشكل كبير لخطر الاستنزاف.[229][230] تؤكد العديد من منظمات الحفاظ على البيئة، من بينها الصندوق الدولي للعناية بالحيوان والجمعية الأمريكية للرفق بالحيوان، أن صيادي الطرائد الهواة، وخاصة من الولايات المتحدة، يلعبون دوراً هاماً]] في تراجع أعداد الزرافات، وهو ما يشيرون إليه "بالانقراض الصامت".[231]

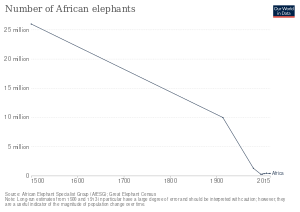

إن الارتفاع في عمليات القتل الجماعي على يد الصيادين الجائرين المتورطين في تجارة العاج غير المشروعة إلى جانب فقدان الموائل يهدد أعداد الأفيال الأفريقية.[232][233] عام 1979، بلغ عدد الفيلة الأفريقية 1.7 مليون حيوان، وفي الوقت الحاضر لم يتبق منها سوى أقل من 400.000.[234] قبل الاستعمار الأوروپي، يعتقد العلماء أن أفريقيا كانت موطناً لحوالي 20 مليون فيل.[235] وبحسب تعداد الفيلة الكبير، اختفى 30% من الفيلة الأفريقية (أو 144.000 حيوان) على مدار فترة سبع سنوات، من عام 2007 حتى 2014.[233][236] قد تنقرض الفيلة الأفريقية بحلول عام 2035 إذا استمرت معدلات الصيد الجائر.[179]

كان للصيد تأثير مدمر على تجمعات العضيات البحرية لعدة قرون حتى قبل انتشار ممارسات الصيد المدمرة والفعالة للغاية مثل الصيد بشباك الجر.[237] يعتبر البشر فريدين من بين المفترسات حيث أنهم يفترسون بانتظام حيوانات أخرى بالغة من المفترسات الرئيسية، وخاصة في البيئات البحرية؛[32] التونة زرقاء الزعنفة، الحوت الأزرق، حوت شمال الأطلسي الصائب،[238] وأكثر من خمسين نوعاً من أسماك القرش والشفنينيات معرضة لضغوط الافتراس من الصيد البشري، وخاصة الصيد التجاري.[239] خلصت نشرتها مجلة ساينس عام 2016 إلى أن البشر يميلون إلى صيد الأنواع الأكبر حجماً، وهذا من شأنه أن يعطل النظم البيئية للمحيطات لملايين السنين.[240] وجدت دراسة نشرتها ساينس أدڤنسز عام 2020 أن حوالي 18% من الحيوانات البحرية الضخمة، بما في ذلك الأنواع الشهيرة مثل القرش الأبيض الكبير، معرضة لخطر الانقراض بسبب الضغوط البشرية على مدار القرن المقبل. وفي أسوأ السيناريوهات، قد ينقرض 40% منها خلال نفس الفترة الزمنية.[241] وبحسب دراسة نشرتها مجلة ناتشر عام 2021، فإن 71% من أسماك القرش والشفنينات المحيطية تدمرت بسبب الصيد الجائر (الدافع الأساسي لفناء الحياة البحرية في المحيطات) من عام 1970 حتى 2018، وهي تقترب من "نقطة اللاعودة" حيث أصبح 24 من أصل 31 نوعاً مهدداً بالانقراض الآن، مع تصنيف العديد منها على أنها معرضة للخطر بشكل حرج.[242][243][244] يتعرض ما يقرب من ثلثي أسماك القرش والشفنينات حول الشعاب المرجانية لخطر الانقراض بسبب الصيد الجائر، حيث يتعرض 14 نوعاً من أصل 134 نوعاً لخطر الانقراض الماحق.[245]

إذا لم يتم التحكم في هذا النمط، فإن المحيطات المستقبلية سوف تفتقر إلى العديد من الأنواع الأكبر حجماً في محيطات اليوم. فالعديد من الأنواع الضخمة تلعب أدواراً بالغة الأهمية في النظم البيئية، وبالتالي فإن انقراضها قد يؤدي إلى سلسلة من الانهيارات البيئية التي قد تؤثر على بنية ووظيفة النظم البيئية المستقبلية بما يتجاوز مجرد فقدان هذه الأنواع.

— جوناثان پاين، أستاذ مشارك ورئيس قسم العلوم الجيولوجية بجامعة ستانفورد[246]

الأمراض

كما تم تحديد تراجع أعداد البرمائيات كمؤشر على التدهور البيئي. بالإضافة إلى فقدان الموائل، والمفترسات المستقدمة والتلوث، فإن الفطريات الأصيصية، وهي عدوى فطرية تنتشر عن طريق الخطأ عن طريق ارتحال البشر،[53] وقد تسببت العولمة وتجارة الحياة البرية في انخفاض حاد في أعداد أكثر من 500 نوع من البرمائيات، وربما انقراض 90 نوعاً،[250] من بينها انتقراض الضفادع الذهبية في كوستاريكا، ضفدع خلد الماء في أستراليا، وضفدع رابي الشجري وانقراض الضفدع الذهبي الپنمي في البرية. انتشرت الفطريات الأصيصية عبر أستراليا، نيوزيلندا، أمريكا الوسطى وأفريقيا، بما في ذلك البلدان ذات التنوع البرمائي الكبير مثل الغابات الضبابية في هندوراس ومدغشقر. Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans هي عدوى مماثلة حالية تهدد السلمندر. أصبحت البرمائيات الآن أكثر مجموعات الفقاريات تعرضاً للخطر، حيث عاشت لأكثر من 300 مليون عام خلال ثلاث حالات انقراض جماعي أخرى.[53]

منذ عام 2012 نفقت ملايين الخفافيش في الولايات المتحدة بسبب عدوى فطرية تُعرف باسم متلازمة الأنف الأبيض والتي انتشرت من الخفافيش الأوروپية، والتي يبدو أنها محصنة ضدها. وقد انخفضت أعداد الخفافيش بنسبة 90% خلال خمس سنوات، ومن المتوقع انقراض نوع واحد على الأقل من الخفافيش. ولا يوجد حالياً أي شكل من أشكال العلاج، وقد وصف آلان هيكس من إدارة حماية البيئة في ولاية نيويورك مثل هذه الانخفاضات بأنها "غير مسبوقة" في تاريخ تطور الخفافيش.[251]

بين عامي 2007 و2013، تم التخلي عن أكثر من عشرة مليون خلية نحل بسبب اضطراب انهيار مستعمرة النحل، مما يتسبب في تخلي شغالات النحل عن الملكة.[252] على الرغم من عدم وجود سبب واحد يحظى بقبول واسع النطاق من قبل المجتمع العلمي، فإن المقترحات تشمل العدوى بعث ڤاروا وأكاراپيس؛ سوء التغذية؛ مسببات الأمراض المختلفة؛ العوامل الوراثية؛ نقص المناعة؛ فقدان الموائل؛ تغيير ممارسات تربية النحل؛ أو مجموعة مجتمعة من تلك العوامل.[253][254]

حسب المنطقة

كانت الحيوانات الضخمة موجودة في جميع قارات العالم، لكنها الآن توجد حصرياً تقريباً في أفريقيا. وفي بعض المناطق، شهدت الحيوانات الضخمة انخفاضًا في أعدادها وسلاسلها الغذائية بعد فترة وجيزة من وصول المستوطنين البشر الأوائل.[59][60] في جميع أنحاء العالم، انقرض 178 نوعاً من أكبر الثدييات في العالم بين عامي 52.000 و9.000 قبل الميلاد؛ وقد قيل إن نسبة أعلى من الحيوانات الضخمة الأفريقية نجت لأنها تطورت جنباً إلى جنب مع البشر.[255][53] يبدو أن توقيت انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة في أمريكا الجنوبية سبق وصول البشر، على الرغم من أن هناك احتمالية بأن يكون النشاط البشري في ذلك الوقت قد أثر على المناخ العالمي بما يكفي للتسبب في مثل هذا الانقراض.[53]

أفريقيا

شهدت أفريقيا أقل انخفاض في أعداد الحيوانات الضخمة مقارنة بالقارات الأخرى. وربما يرجع هذا إلى فكرة مفادها أن الحيوانات الضخمة الأفروآسيوية تطورت جنبًا إلى جنب مع البشر، وبالتالي طورت خوفاً صحياً منهم، على عكس الحيوانات المستأنسة نسبياً في القارات الأخرى.[255][256]

أوراسيا

على عكس القارات الأخرى، انقرضت الحيوانات الضخمة في أوراسيا على مدى فترة طويلة نسبيًا من الزمن، ربما بسبب التقلبات المناخية التي أدت إلى تفتيت وتناقص أعدادها، مما جعلها عرضة للاستغلال المفرط، كما حدث مع بيسون السهوب.[257] تسبب الاحترار في منطقة القطب الشمالي في التراجع السريع للمراعي، الأمر الذي كان له تأثيراً سلبياً على الحيوانات الضخمة التي ترعى في أوراسيا. وتحولت معظم الأراضي التي كانت في السابق سهول الماموث إلى مستنقعات، مما جعل البيئة غير قادرة على دعمها، ولا سيما الماموث الصوفي.[258] ومع ذلك، فقد نجت كل هذه الحيوانات الضخمة من فترات جليدية سابقة بنفس درجة الاحترار أو بدرجة أشد، مما يشير إلى أنه حتى خلال الفترات الدافئة، ربما كانت الملاجئ موجودة وأن الصيد البشري ربما كان العامل الحاسم في انقراضها.

في منطقة غرب المتوسط، بدأ تدهور الغابات الناجم عن الأنشطة البشرية منذ حوالي 4000 سنة قبل الميلاد، خلال العصر النحاسي، وأصبح واضحاً بشكل خاص خلال الفترة الرومانية. تنبع أسباب تدهور النظم البيئية للغابات من الزراعة والرعي والتعدين.[259] خلال السنوات الأخيرة من عهد الإمبراطورية الرومانية الغربية، تعافت الغابات في شمال غرب أوروپا من الخسائر التي تكبدتها طوال الفترة الرومانية، على الرغم من استئناف إزالة الغابات على نطاق واسع مرة أخرى حوالي عام 800 قبل الميلاد، خلال العصور الوسطى العليا.[260]

في جنوب الصين، يُعتقد أن استخدام البشر للأراضي قد أدى إلى تغيير دائم في اتجاه ديناميكيات الغطاء النباتي في المنطقة، والتي كانت تحكمها في السابق درجات الحرارة. ويتضح هذا من خلال التدفقات العالية للفحم من تلك الفترة الزمنية.[261]

الأمريكتان

كان هناك نقاش حول مدى إمكانية عزو اختفاء الحيوانات الضخمة في نهاية العصر الجليدي الأخير إلى الأنشطة البشرية سواء صيد، أو حتى ذبح[ب] مجموعات الفرائس. وقد تسببت الاكتشافات في مونتى ڤردى بأمريكا الجنوبية وفي ملجأ ميدوكروفت الصخري بولاية پنسلڤانيا الأمريكية في إثارة الجدل[262] فيما يتعلق بحضارة كلوڤيس، فمن المحتمل أن تكون هناك مستوطنات بشرية كلوڤيسية، وربما يمتد تاريخ البشر في الأمريكتين إلى آلاف السنين قبل حضارة كلوڤيس.[262] لا يزال الجدل قائمًا حول مدى الارتباط بين وصول البشر وانقراض الحيوانات الضخمة: على سبيل المثال، في جزيرة رانڤل بسيبيريا، انقراض الماموث الصوفي القزم (حوالي 2000 ق.م.)[263]

ولم يتزامن الانقراض الجماعي للحيوانات الضخمة مع وصول البشر، كما لم يتزامن انقراضهم في أمريكا الجنوبية، على الرغم من اقتراح أن التغيرات المناخية الناجمة عن التأثيرات البشرية في أماكن أخرى من العالم ربما ساهمت في ذلك.[53]

تُعقد أحياناً مقارنات بين الانقراضات الحديثة (منذ الثورة الصناعية تقريباً) وانقراض العصر الپلایستوسيني قرب نهاية العصر الجليدي الأخير. ويتجلى هذا الأخير في انقراض الحيوانات العاشبة الكبيرة مثل الماموث الصوفي وآكلات اللحوم التي افترستها. كان البشر في هذا العصر يصطادون الماموث والماستدون بنشاط،[264] لكن من غير المعروف ما إذا كان هذا الصيد هو السبب في التغيرات البيئية الضخمة اللاحقة، والانقراضات الواسعة النطاق، والتغيرات المناخية.[55][56]

لم تكن الأنظمة البيئية التي واجهها الأمريكان الأوائل معرضة للتفاعل البشري، وربما كانت أقل قدرة على الصمود في مواجهة التغيرات التي أحدثها البشر مقارنة بالأنظمة البيئية التي واجهها البشر في العصر الصناعي. وبالتالي، فإن تصرفات شعب كلوڤيس، على الرغم من أنها تبدو غير مهمة وفقًا لمعايير اليوم، ربما كانت لها بالفعل تأثيرات عميقة على الأنظمة البيئية والحياة البرية التي لم تكن معتادة على الإطلاق على التأثير البشري.[53]

في يوكون، انهار النظام البيئي لسهوب الماموث بين 13.500-10.000 سنة مضت، على الرغم من أن الخيول البرية والماموث الصوفي استمرت بطريقة ما في المنطقة لآلاف السنين بعد هذا الانهيار.[265] في ما يعرف الآن بولاية تكساس، حدث انخفاض في التنوع الحيوي المحلي للنباتات والحيوانات أثناء فترة برودة عصر درياس الأصغر، ورغم تعافي التنوع النباتي بعد عصر درياس الأصغر، فإن التنوع الحيواني لم يتعافى.[266] في جزر القنال بكاليفورنيا، انقرضت العديد من الأنواع البرية في نفس الوقت تقريباً الذي وصل فيه البشر، لكن الأدلة المباشرة على وجود سبب بشري لانقراضها لا تزال مفقودة.[267] في الغابات الجبلية في جبال الأنديز الكولومبية، تشير أبواغ الفطريات الكوپروفيلية إلى انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة الذي حدث في موجتين، الأولى حدثت منذ حوالي 22.900 سنة مضت والثانية حدثت منذ حوالي 10.990 سنة مضت.[268] وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2023 حول انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة في هضبة جونين في پيرو أن توقيت اختفاء الحيوانات الضخمة كان متزامناً مع ارتفاع كبير في نشاط الحرائق المنسوب إلى أنشطة بشرية، مما يشير إلى أن البشر هم سبب الانقراض المحلي للحيوانات الضخمة على الهضبة.[269]

غينيا الجديدة

استخدم البشر في غينيا الجديدة تربة مخصبة بركانية في أعقاب ثورات بركانية كبرى وتدخلوا في أنماط تعاقب النباتات منذ أواخر العصر الپلستوسيني، مع تكثيف هذه العملية في العصر الهولوسيني.[270]

أستراليا

كانت أستراليا ذات يوم موطناً لمجموعة كبيرة من الحيوانات الضخمة، والتي تشبه إلى حد كبير تلك الموجودة في القارة الأفريقية اليوم. تتميز الحياة الحيوية لأستراليا بالثدييات الجرابية بشكل أساسي، والعديد من الزواحف والطيور، وكلها كانت موجودة بأشكال عملاقة حتى وقت قريب. وصل السكان الأصليون الأستراليون إلى القارة في وقت مبكر جداً، منذ حوالي 50.000 سنة.[53] إن مدى مساهمة وصول البشر مثير للجدل؛ حيث كان الجفاف المناخي لأستراليا منذ 40.000-60.000 سنة سبباً غير محتمل، حيث كان أقل حدة في السرعة أو الحجم من تغير المناخ الإقليمي السابق الذي فشل في القضاء على الحيوانات الضخمة. استمرت حالات الانقراض في أستراليا منذ الاستيطان الأصلي حتى اليوم في كل من النباتات والحيوانات، بينما انخفضت أعداد الكثير من الحيوانات والنباتات أو أصبحت معرضة للخطر.[271]

وبسبب الإطار الزمني الأقدم وكيمياء التربة في القارة، فإن الأدلة على الحفاظ على الأحفوريات الفرعية قليلة جداً مقارنة بأماكن أخرى.[272] ومع ذلك، حدث انقراض على مستوى القارة لجميع الأجناس التي يزيد وزنها عن 100 كيلوجرام، وستة من سبعة أجناس يتراوح وزنها بين 45 و100 كيلوجرام منذ حوالي 46.400 سنة (بعد 4000 سنة من وصول البشر)[273] والحقيقة أن الحيوانات الضخمة بقيت على قيد الحياة حتى وقت لاحق على جزيرة تسمانيا بعد إنشاء جسر بري[274] مما يشير إلى أن الصيد المباشر أو تعطيل النظام البيئي بواسطة البشر مثل زراعة العصي النارية من الأسباب المحتملة. نُشر أول دليل على الافتراس البشري المباشر الذي أدى إلى الانقراض في أستراليا عام 2016.[275]

وجدت دراسة أجريت عام 2021 أن معدل انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة في أستراليا غير عادي إلى حد ما، حيث انقرضت بعض الأنواع العامة في وقت سابق بينما انقرضت الأنواع المتخصصة للغاية في وقت لاحق أو حتى لا تزال على قيد الحياة حتى اليوم. وقد أُقترح سبب فسيفسائي للانقراض مع ضغوط بشرية وبيئية مختلفة.[276]

الكاريبي

وصول الإنسان إلى منطقة الكاريبي منذ حوالي 6000 سنة مضت يرتبط بانقراض العديد من الأنواع.[277] تشمل هذه الأنواع العديد من الأجناس المختلفة من الكسلان الأرضي والشجري في منطقة الكاريبي عبر جميع الجزر. كانت هذه الكسلان أصغر حجماً بشكل عام من تلك الموجودة في أمريكا الجنوبية. كان جنس الكسلان الكبير هو الأكبر حجماً حيث بلغ وزنه 90 كجم، وكان جنس Acratocnus من الأقارب متوسطي الحجم للكسلان ثنائي الأصابع الحديث المتوطن في كوبا، وجنس Imagocnus أيضاً في كوبا، وجنس Neocnus والعديد من الأنواع الأخرى.[278]

ماكرونيزيا

شهد وصول أول المستوطنين البشر إلى الآزور إدخال النباتات المجتاحة والماشية إلى الأرخبيل، مما أدى إلى انقراض نوعين من النباتات على الأقل في جزيرة پيكو.[279] على جزيرة فايال، افترض بعض العلماء أن تراجع أشجار كرز الغار كان مرتبطًا بنوع الشجرة الذي ينتمي إلى جنس داخلي، مع استئصال أو انقراض أنواع مختلفة من الطيور مما حد بشكل كبير من انتشار بذورها.[280] تعرضت النظم البيئية للبحيرات للدمار بسبب الاستعمار البشري، كما يتضح من نظائر الهيدروجين من الأحماض الدهنية C30 التي سجلت مياه القاع الخالية من الأكسجين بسبب التغذية الزائدة في بحيرة فوندا في جزيرة فلورس بدءًا من عام 1500 حتى 1600 م.[281]

أدى وصول البشر إلى أرخبيل ماديرا إلى انقراض ما يقرب من ثلثي أنواع الطيور المتوطنة، مع استئصال نوعين من الطيور غير المتوطنة محلياً من الأرخبيل.[282] من بين أربعة وثلاثين نوعاً من الحلزونات الأرضية التي جمُعت في عينة أحفورية فرعية من شرق جزيرة ماديرا، انقرضت تسعة أنواع بعد وصول البشر.[283] وعلى جزر دزرتاس، من بين خمسة وأربعين نوعاً من الحلزونات الأرضية المعروفة بوجودها قبل الاستعمار البشري، انقرضت ثمانية عشر نوعاً ولم تعد خمسة أنواع موجودة على الجزر.[284] ربما نجا نبات "اليوريا ستيگموسا"، الذي يُعزى انقراضه عادةً إلى تغير المناخ بعد نهاية العصر الپلستوسيني وليس البشر، حتى استعمار الأرخبيل من قبل الپرتغاليين وانقرض نتيجة للنشاط البشري.[285] أعتبرت الفئران المستقدمة السبب الرئيسي للانقراض في جزيرة ماديرا بعد اكتشافها واستيطان البشر لها.[282]

في جزر الكناري، تدمرت الغابات الأصلية المحبة للحرارة وانقرض نوعين من الأشجار بعد وصول البشر الأوائل إليها، وذلك في المقام الأول نتيجة لزيادة وتيرة إزالة الحرائق وتآكل التربة واستقدام الخنازير والماعز والجرذان المجتاحة. تسارعت عمليات استقدام الأنواع المجتاحة خلال عصر الاكتشاف عندما استوطن الأوروپيون الأرخبيل المكارونيزي لأول مرة. على الرغم من أن غابات الغار في الأرخبيل لا تزال متأثرة سلباً، إلا أنها كانت أفضل حالاً بسبب كونها أقل ملاءمة للاستخدام الاقتصادي البشري.[286]

الرأس الأخضر، مثل جزر الكناري، شهدت إزالة الغابات بشكل حاد عند وصول المستوطنين الأوروپيين والأنواع المجتاحة المختلفة التي جلبوها إلى الأرخبيل،[287] مع تعرض الغابات المحبة للحرارة في الأرخبيل لأكبر قدر من الدمار.[286] وقد عُزيت الأسباب الرئيسية للدمار البيئي في الرأس الأخضر إلى الأنواع المجتاحة، والرعي الجائر، وزيادة حوادث الحرائق، وتدهور التربة.[287][288]

الهادي

تشير الحفريات الأثرية والحفريات في 70 جزيرة مختلفة من جزر المحيط الهادي إلى أن العديد من الأنواع انقرضت مع انتقال البشر عبر المحيط، بدءاً من 30.000 سنة في أرخبيل بسمارك وجزر سليمان.[289] وتشير التقديرات الحالية إلى أن نحو 2000 نوع من أنواع الطيور في المحيط الهادي انقرضت منذ وصول البشر، وهو ما يمثل انخفاضاً بنسبة 20% في التنوع الحيوي للطيور في جميع أنحاء العالم.[290]

في پولينيزيا، لم يهدأ تراجع أعداد الطيور في أواخر العصر الهولوسيني إلا بعد أن استنزفت بشكل كبير وأصبح هناك عدد أقل بشكل متزايد من أنواع الطيور القابلة للانقراض.[291] كما تم القضاء على الإگوانا بسبب انتشار البشر.[292] علاوة على ذلك، فإن الحيوانات المتوطنة في أرخبيلات المحيط الهادي معرضة للخطر بشكل استثنائي في العقود القادمة بسبب ارتفاع مستوى سطح البحر الناجم عن االحترار العالمي.[293]

فقدت جزيرة لورد هاو، التي ظلت غير مأهولة بالسكان حتى وصول الأوروپيين إلى جنوب المحيط الهادي في القرن الثامن عشر، الكثير من الطيور المتوطنة فيها عندما أصبحت محطة لصيد الحيتان في أوائل القرن التاسع عشر. كما حدثت موجة أخرى من انقراض الطيور في أعقاب إدخال الفئران السوداء عام 1918.[294]

انقرضت السلاحف الميولانية الضخمة المتوطنة في ڤانواتو فور وصول البشر إليها، وعُثر على بقايا منها تحتوي على أدلة على ذبح البشر لها.[295]

كان وصول البشر إلى كاليدونيا الجديدة بمثابة بداية تراجع الغابات الساحلية وأشجار المانجروف على الجزيرة.[296] كانت الحيوانات الضخمة في الأرخبيل لا تزال موجودة عندما وصل البشر، لكن الأدلة التي لا تقبل الجدل على أن انقراضها كان بفعل البشر لا تزال بعيدة المنال.[297]

في فيجي، استسلمت كل من الإگوانا العملاقة من نوعي Brachylophus gibbonsi وLapitiguana impensa للانقراض الناجم عن الأنشطة البشرية بعد وقت قصير من مواجهة البشر الأوائل على الجزيرة.[298]

في ساموا الأمريكية، تحتوي الرواسب التي يعود تاريخها إلى فترة الاستيطان البشري الأولي على كميات كبيرة من بقايا الطيور والسلاحف والأسماك الناجمة عن زيادة ضغط الافتراس.[299]

في جزيرة مانگايا ضمن مجموعة جزر كوك، ارتبط الاستعمار البشري بانقراض كبير للطيور المتوطنة،[300] إلى جانب إزالة الغابات وتآكل التلال البركانية وزيادة تدفق الفحم، مما تسبب في أضرار بيئية إضافية.[301]

على جزيرة راپا في الأرخبيل الجنوبي، يرتبط وصول البشر، الذي تميز بزيادة الفحم وحبوب لقاح القلقاس في سجل أحفورات حبوب اللقاح، بانقراض نوع متوطن من النخيل.[302]

جزيرة هندرسون، التي كان يُعتقد ذات يوم أنها لم يمسسها البشر، استعمرها الپولينيزيون ثم هجروها فيما بعد. ويُعتقد أن الانهيار البيئي في الجزيرة الناجم عن الانقراضات البشرية كان سبباً في هجران الجزيرة.[303]

يُعتقد أن أول مستوطن بشري في جزر هاواي وصل في الفترة 300-800 م، مع وصول الأوروپيين في القرن السادس عشر. تشتهر هاواي بتنوعها الحيوي من النباتات والطيور والحشرات والرخويات والأسماك؛ حيث إن 30% من العضيات الموجودة بها متوطنة. كما أن العديد من أنواعها معرضة للخطر أو انقرضت، ويرجع ذلك في المقام الأول إلى الأنواع التي أستقدمت عن طريق الخطأ ورعي الماشية. كما انقرضت أكثر من 40% من أنواع الطيور الموجودة بها، كما أنها موطن لنحو 75% من حالات الانقراض في الولايات المتحدة.[304] تشير الأدلة إلى أن استقدام الفئران الپولينيزية كان، قبل كل شيء، سبباً في الإبادة البيئية للغابات المتوطنة في الأرخبيل.[305] لقد زادت معدلات الانقراض في هاواي على مدى المائتي سنة الماضية وتم توثيق ذلك بشكل جيد نسبياً، حيث استخدمت الانقراضات بين القواقع الأصلية كتقديرات لمعدلات الانقراض العالمية.[70] وقد أدت المعدلات المرتفعة لتجزئة الموائل في الأرخبيل إلى انخفاض التنوع الحيوي بشكل أكبر.[306]

من المرجح أن يتسارع انقراض الطيور المتوطنة في هاواي بشكل أكبر مع إضافة الاحترار العالمي الناجم عن الأنشطة البشرية المزيد من الضغوط على رأس تغييرات استخدام الأراضي والأنواع المجتاحة.[307]

مدغشقر

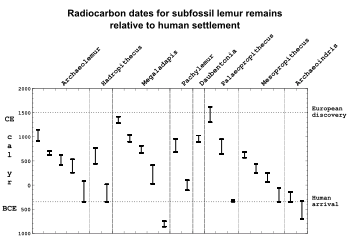

في غضون قرون من وصول البشر حوالي الألفية الأولى الميلادية، انقرضت تقريباً جميع الحيوانات الضخمة المتميزة والمتوطنة والمنعزلة جغرافياً في مدغشقر.[308]

انقرضت أكبر الحيوانات، التي يزيد وزنها عن 150 كجم، بعد وقت قصير جداً من وصول البشر الأول، مع انقراض الأنواع الكبيرة والمتوسطة الحجم بعد ضغوط الصيد المطولة من البشر المتزايدين الذين انتقلوا إلى مناطق أكثر بعداً من الجزيرة منذ حوالي 1000 سنة. بالإضافة إلى 17 نوعاً من الليمور "العملاق". كان وزن بعض هذه الليمورات يزيد عن 150 كجم، وقد قدمت حفرياتها دليلاً على ذبح البشر للعديد من الأنواع.[309]من بين الحيوانات الضخمة الأخرى الموجودة على الجزيرة أفراس النهر الملاجاشية بالإضافة إلى طيور الفيل الكبير التي لا تطير، ويُعتقد أن كلتا المجموعتين انقرضتا في الفترة 750-1050 م.[308] شهدت الحيوانات الأصغر حجماً زيادات أولية بسبب انخفاض المنافسة، ثم انخفاضات لاحقة على مدار 500 سنة الماضية.[60] انقرضت جميع الحيوانات التي يزيد وزنها عن 10 كجم. والأسباب الرئيسية لتدهور العضيات في مدغشقر، والتي كانت في ذلك الوقت تعاني بالفعل من قحولة المناخ الطبيعية،[310] حيث كان قيام البشر بأنشطة الصيد،[311][312] والرعي،[313][312] والزراعة،[311] وإزالة الغابات،[313] جميعها لا تزال قائمة وتهدد الأنواع المتبقية في مدغشقر اليوم. كما تأثرت النظم البيئية الطبيعية في مدغشقر ككل بشكل أكبر بسبب زيادة حالات الحرائق نتيجة لإنشعال الحرائق من صنع البشر؛ تشير الأدلة من بحيرة أمباريهبى في جزيرة نوسي بى إلى تحول في الغطاء النباتي المحلي من الغابات المطيرة السليمة إلى رقعة من الأراضي العشبية والغابات المضطربة بسبب الحرائق بين عامي 1300 و1000 ق.م.[314]

نيوزيلندا

تتميز نيوزيلندا بعزلتها الجغرافية وجغرافيتها الحيوية الجزرية، وكانت معزولة عن البر الرئيسي لأستراليا لمدة 80 مليون عام. كانت آخر كتلة يابس كبيرة استعمرها البشر. عند وصول المستوطنين الپولينيزييين في أواخر القرن الثالث عشر، عانت العضيات الأصلية من تدهور كارثي بسبب إزالة الغابات والصيد وإدخال الأنواع المجتاحة.[315][316] حدث انقراض جميع الطيور الضخمة في الجزر بعد عدة مئات من السنين من وصول البشر.[317] كانت الموا، وهي طيور كبيرة غير قادرة على الطيران، مزدهرة خلال العصر الهولوسيني المتأخر،[318] لكنها انقرضت في غضون 200 سنة من وصول المستوطنون البشر،[59] وكذلك الأمر مع نسر هاست الضخم، المفترس الأساسي لهم، وما لا يقل عن نوعين من الأوز الكبير الغير قادرة على الطيران. كما أدخل الپولينيزيون الجرذ الپولينيزي. ربما وضع هذا بعض الضغط على الطيور الأخرى، لكن في وقت الاتصال الأوروپي المبكر (القرن الثامن عشر) والاستعمار (القرن التاسع عشر)، كانت حياة الطيور غزيرة.[317] حدث انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة بسرعة كبيرة على الرغم من كثافة السكان الصغيرة للغاية، والتي لم تتجاوز أبداً 0.01 شخص لكل كم2.[319] أعقب انقراض الطفيليات انقراض الحيوانات الضخمة في نيوزيلندا.[320] جلب الأوروپيون معهم أنواعاً مختلفة من الأنواع المجتاحة بما في ذلك فئران السفن، والبوسوم، والقطط، وابن عرس التي دمرت حياة الطيور الأصلية، والتي تكيف بعضها مع عدم القدرة على الطيران وعادات التعشيش على الأرض، ولم يكن لديها سلوك دفاعي نتيجة لعدم وجود مفترسات ثديية محلية. الكاكاپو، أكبر ببغاء في العالم، والذي لا يطير، لا يوجد الآن إلا في محميات التربية المُدارة. الشعار الوطني لنيوزيلندا، طائر الكيوي، مدرج على قائمة الطيور المهددة بالانقراض.[317]

التخفيف من آثاره

تثبيت تعداد السكان؛[321][322][323] والسيطرة على الرأسمالية،[149][152][324] وتخفيض المطالب الاقتصادية،[31][325] وتحويلها إلى أنشطة اقتصادية ذات تأثيرات منخفضة على التنوع الحيوي؛[326] والانتقال إلى الحميات النباتية؛[45][46] وزيادة عدد وحجم المناطق المحمية البرية والبحرية[327][328] اقترحت كوسائل لتجنب أو الحد من فقدان التنوع الحيوي والانقراض الجماعي السادس المحتمل.

يقترح رودولفو ديرزو وپول إهرليتش أن "العلاج الأساسي والضروري و"البسيط" الوحيد ... هو تقليص حجم المشروع البشري".[108] وفقًا لورقة بحثية نشرتها فرونتيرز ميديا عام 2021، فإن البشرية تواجه الأنشطة الصناعية والبشرية بسرعة.[97][329]

وقد أُتقرح الحد من النمو السكاني البشري كوسيلة للتخفيف من تغير المناخ وأزمة التنوع الحيوي،[330][331][332] على الرغم من اعتقاد العديد من العلماء أن هذا الاقتراح تم تجاهله إلى حد كبير في الخطاب السياسي السائد.[333][334] هناك اقتراح بديل يتمثل في زيادة كفاءة الزراعة واستدامتها. إذ يمكن تحويل الكثير من الأراضي غير الصالحة للزراعة إلى أراضي صالحة للزراعة لزراعة المحاصيل الغذائية. ومن المعروف أيضاً أن الفطر يعمل على إصلاح التربة التالفة.

دعت مقالة نشرتها مجلة ساينس عام 2018 المجتمع العالمي إلى تحديد 30% من الكوكب بحلول عام 2030، و50% بحلول عام 2050، كمناطق محمية للتخفيف من أزمة الانقراض المعاصرة. وسلطت الضوء على أن عدد السكان من المتوقع أن ينمو إلى 10 بليون بحلول منتصف القرن، ومن المتوقع أن يتضاعف استهلاك الموارد الغذائية والمياه بحلول هذا الوقت.[335] حذر تقريرا نشرته مجلة ساينس عام 2022 من أن 44% من سطح الأرض، أو 64 مليون كم²، يجب الحفاظ عليها وجعلها "سليمة بيئياً" لمنع المزيد من فقدان التنوع الحيوي.[336][337]

في نوفمبر 2018، حثت رئيسة التنوع الحيوي في الأمم المتحدة كرستينا پاسكا پالمر الناس في جميع أنحاء العالم على الضغط على الحكومات لتنفيذ تدابير حماية كبيرة للحياة البرية بحلول عام 2020. ووصفت فقدان التنوع الحيوي بأنه "قاتل صامت" لا يقل خطورة عن الاحترار العالمي، لكنها قالت أنه لم يحظ باهتمام كبير بالمقارنة. وأضافت پالمر: "إنه مختلف عن تغير المناخ، حيث يشعر الناس بالتأثير في الحياة اليومية. مع التنوع الحيوي، ليس الأمر واضحاً جداً ولكن بحلول الوقت الذي تشعر فيه بما يحدث، قد يكون الأوان قد فات".[338] في يناير 2020، صاغت اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة للتنوع الحيوي خطة على غرار اتفاقية پاريس لوقف التنوع الحيوي وانهيار النظام البيئي من خلال تحديد الموعد النهائي بحلول 203 لحماية 30% من أراضي ومحيطات الأرض والحد من التلوث بنسبة 50%، بهدف السماح باستعادة النظم البيئية بحلول عام 2050. فشل العالم في تحقيق أهداف آيتشي للتنوع الحيوي لعام 2020 التي حددتها الاتفاقية خلال قمة عُقدت في اليابان عام 2010.[339][340] من بين الأهداف العشرين المقترحة للتنوع الحيوي، تم "تحقيق" ستة أهداف فقط "جزئياً" بحلول الموعد النهائي.[341] وقد وصفته إنگر أندرسن ، رئيس برنامج الأمم المتحدة للبيئة، بالفشل العالمي:

"من كوڤيد-19 إلى حرائق الغابات الهائلة والفيضانات وذوبان الأنهار الجليدية ودرجات الحرارة الغير مسبوقة، فإن فشلنا في تلبية أهداف اتفاقية التنوع الحيوي لحماية موطننا له عواقب حقيقية للغاية. لم يعد بوسعنا أن نتحمل إهمال الطبيعة".[342]

وقد اقترح بعض العلماء إبقاء معدل الانقراض أقل من 20 حالة سنوياً خلال القرن القادم كهدف عالمي للحد من فقدان الأنواع، وهو ما يعادل في التنوع الحيوي هدف المناخ 2 درجة مئوية، على الرغم من أنه لا يزال أعلى بكثير من المعدل الطبيعي للخلفية وهو درجتين سنوياً قبل التأثيرات البشرية على عالم الطبيعة.[343][344]

وجد تقرير صادر عن IPBES في أكتوبر 2020 حول "عصر الأوبئة" أن العديد من الأنشطة البشرية نفسها التي تساهم في فقدان التنوع الحيوي وتغير المناخ، بما في ذلك إزالة الغابات وتجارة الحياة البرية، قد زادت أيضاً من خطر الأوبئة في المستقبل. يقدم التقرير العديد من الخيارات السياسية للحد من مثل هذه المخاطر، مثل فرض الضرائب على إنتاج واستهلاك اللحوم، واتخاذ إجراءات صارمة ضد تجارة الحياة البرية غير المشروعة، وإزالة الأنواع عالية الخطورة المسببة للأمراض من تجارة الحياة البرية القانونية، وإلغاء الإعانات للشركات الضارة بالبيئة.[345][346][347] وفقًا لعالم الحيوانات البحرية جون سبايسر، فإن "أزمة جائحة كوڤيد-19 ليست مجرد أزمة أخرى إلى جانب أزمة التنوع الحيوي وأزمة تغير المناخ. لا تخطئوا، فهذه أزمة كبيرة - أعظم أزمة واجهها البشر على الإطلاق".[345]

في ديسمبر 2022، كانت كل الدول تقريباً على وجه الأرض، باستثناء الولايات المتحدة والكرسي الرسولي،[348] قد وقعت على إطار عمل كونمينگ-مونتريال العالمي للتنوع الحيوي الذي صيغ في مؤتمر الأمم المتحدة للتنوع الحيوي 2022 (COP 15) والتي تتضمن حماية 30% من الأراضي والمحيطات بحلول عام 2030 و22 هدفاً آخر تهدف إلى التخفيف من أزمة الانقراض. والاتفاقية أضعف من أهداف آيتشي لاتفاقية التنوع الحيوي لعام 2010.[349][350] وقد تعرضت لانتقادات من بعض البلدان بسبب استعجالها وعدم بذلها جهوداً كافية لحماية الأنواع المهددة بالانقراض.[349]

انظر أيضاً

- العصر البشري

- فقدان التنوع الحيوي

- إبادة بيئية

- تمرد الانقراض

- خطر الانقراض من تغير المناخ

- رمز الانقراض

- الانقراض: الحقائق (وثائقي 2020)

- تأثير الإنسان على البيئة

- قوائم الأنواع المنقرضة

- إعادة الحياة البرية في الپلستوسين

- انقراض العصر الرباعي

- انقراض السباق (وثائقي 2015)

- خط زمني للانقراضات في الهولوسين

- تحذير علماء العالم للبشرية

الهوامش

- ^ Phylogenetic diversity (PD) is the sum of the phylogenetic branch lengths in years connecting a set of species to each other across their phylogenetic tree, and measures their collective contribution to the tree of life.

- ^ This may refer to groups of animals endangered by climate change. For example, during a catastrophic drought, remaining animals would be gathered around the few remaining watering holes, and thus become extremely vulnerable.

المصادر

- ^ Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. London: A & C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1999). "Up to the Starting Line". Guns, Germs, and Steel. W.W. Norton. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-393-31755-8.

- ^ Wagler, Ron (2011). "The Anthropocene Mass Extinction: An Emerging Curriculum Theme for Science Educators". The American Biology Teacher. 73 (2): 78–83. doi:10.1525/abt.2011.73.2.5. S2CID 86352610. Archived from the original on 2022-02-05.

- ^ Walsh, Alistair (January 11, 2022). "What to expect from the world's sixth mass extinction". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Julia (June 11, 2019). "Almost 600 plant species have become extinct in the last 250 years". CNN. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

The research – published Monday in Nature, Ecology & Evolution journal – found that 571 plant species have disappeared from the wild worldwide, and that plant extinction is occurring up to 500 times faster than the rate it would without human intervention.

- ^ Guy, Jack (September 30, 2020). "Around 40% of the world's plant species are threatened with extinction". CNN. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (August 31, 2021). "Up to half of world's wild tree species could be at risk of extinction". The Guardian. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Marine Extinctions: Patterns and Processes – an overview. 2013. CIESM Monograph 45 [1]

- ^ Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R. (8 June 2018). "The misunderstood sixth mass extinction". Science. 360 (6393): 1080–1081. Bibcode:2018Sci...360.1080C. doi:10.1126/science.aau0191. OCLC 7673137938. PMID 29880679. S2CID 46984172.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Pimm SL, Jenkins CN, Abell R, Brooks TM, Gittleman JL, Joppa LN, Raven PH, Roberts CM, Sexton JO (30 May 2014). "The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection" (PDF). Science. 344 (6187): 1246752-1–1246752-10. doi:10.1126/science.1246752. PMID 24876501. S2CID 206552746. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

The overarching driver of species extinction is human population growth and increasing per capita consumption.

- ^ أ ب Pimm, Stuart L.; Russell, Gareth J.; Gittleman, John L.; Brooks, Thomas M. (1995). "The Future of Biodiversity". Science. 269 (5222): 347–350. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..347P. doi:10.1126/science.269.5222.347. PMID 17841251. S2CID 35154695.

- ^ أ ب Teyssèdre, Anne (2004). Toward a sixth mass extinction crisis? Chapter 2 in Biodiversity & global change : social issues and scientific challenges. R. Barbault, Bernard Chevassus-au-Louis, Anne Teyssèdre, Association pour la diffusion de la pensée française. Paris: Adpf. pp. 24–49. ISBN 2-914935-28-5. OCLC 57892208.

- ^ أ ب De Vos, Jurriaan M.; Joppa, Lucas N.; Gittleman, John L.; Stephens, Patrick R.; Pimm, Stuart L. (2014-08-26). "Estimating the normal background rate of species extinction" (PDF). Conservation Biology (in الإسبانية). 29 (2): 452–462. Bibcode:2015ConBi..29..452D. doi:10.1111/cobi.12380. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 25159086. S2CID 19121609. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Barnosky, Anthony D.; García, Andrés; Pringle, Robert M.; Palmer, Todd M. (19 June 2015). "Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction". Science Advances. 1 (5): e1400253. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0253C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253. PMC 4640606. PMID 26601195.

All of these are related to human population size and growth, which increases consumption (especially among the rich), and economic inequity.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund (September 10, 2020). "Bending the curve of biodiversity loss". Living Planet Report 2020. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022.

- ^ Raven, Peter H.; Chase, Jonathan M.; Pires, J. Chris (2011). "Introduction to special issue on biodiversity". American Journal of Botany. 98 (3): 333–335. doi:10.3732/ajb.1100055. PMID 21613129.

- ^ Rosenberg KV, Dokter AM, Blancher PJ, Sauer JR, Smith AC, Smith PA, Stanton JC, Panjabi A, Helft L, Parr M, Marra PP (2019). "Decline of the North American avifauna". Science. 366 (6461): 120–124. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..120R. doi:10.1126/science.aaw1313. PMID 31604313. S2CID 203719982.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Barnosky, Anthony D.; Matzke, Nicholas; Tomiya, Susumu; Wogan, Guinevere O. U.; Swartz, Brian; Quental, Tiago B.; Marshall, Charles; McGuire, Jenny L.; Lindsey, Emily L.; Maguire, Kaitlin C.; Mersey, Ben; Ferrer, Elizabeth A. (3 March 2011). "Has the Earth's sixth mass extinction already arrived?". Nature. 471 (7336): 51–57. Bibcode:2011Natur.471...51B. doi:10.1038/nature09678. PMID 21368823. S2CID 4424650.

- ^ Briggs, John C (October 2017). "Emergence of a sixth mass extinction?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (in الإنجليزية). 122 (2): 243–248. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blx063. ISSN 0024-4066. Archived from the original on 2022-06-18. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ أ ب Cowie, Robert H.; Bouchet, Philippe; Fontaine, Benoît (2022). "The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation?". Biological Reviews. 97 (2): 640–663. doi:10.1111/brv.12816. PMC 9786292. PMID 35014169. S2CID 245889833.

Our review lays out arguments clearly demonstrating that there is a biodiversity crisis, quite probably the start of the Sixth Mass Extinction.

- ^ أ ب Strona, Giovanni; Bradshaw, Corey J. A. (2022). "Coextinctions dominate future vertebrate losses from climate and land use change". Science Advances. 8 (50): eabn4345. Bibcode:2022SciA....8N4345S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abn4345. PMC 9757742. PMID 36525487.

The planet has entered the sixth mass extinction.

- ^ أ ب Rampino, Michael R.; Shen, Shu-Zhong (5 September 2019). "The end-Guadalupian (259.8 Ma) biodiversity crisis: the sixth major mass extinction?". Historical Biology. 33 (5): 716–722. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1658096. S2CID 202858078. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Seventh Mass Extinction? Severe and Deadly Event 260 Million Years Ago Discovered by Scientists". Newsweek. 9 October 2019. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ أ ب Faurby, Søren; Svenning, Jens-Christian (2015). "Historic and prehistoric human-driven extinctions have reshaped global mammal diversity patterns". Diversity and Distributions. 21 (10): 1155–1166. Bibcode:2015DivDi..21.1155F. doi:10.1111/ddi.12369. hdl:10261/123512. S2CID 196689979.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian; Lemoine, Rhys T.; Bergman, Juraj; Buitenwerf, Robert; Le Roux, Elizabeth; Lundgren, Erick; Mungi, Ninad; Pedersen, Rasmus Ø. (2024). "The late-Quaternary megafauna extinctions: Patterns, causes, ecological consequences and implications for ecosystem management in the Anthropocene". Cambridge Prisms: Extinction (in الإنجليزية). 2. doi:10.1017/ext.2024.4. ISSN 2755-0958.

- ^ Cooke, Rob; Sayol, Ferran; Andermann, Tobias; Blackburn, Tim M.; Steinbauer, Manuel J.; Antonelli, Alexandre; Faurby, Søren (2023-12-19). "Undiscovered bird extinctions obscure the true magnitude of human-driven extinction waves". Nature Communications (in الإنجليزية). 14 (1): 8116. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.8116C. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43445-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10730700. PMID 38114469.

- ^ Gemma, Conroy (December 19, 2023). "Humans might have driven 1,500 bird species to extinction — twice previous estimates". Nature. Archived from the original on January 16, 2024. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ McNeill, John Robert; Engelke, Peter (2016). The Great Acceleration: An Environmental History of the Anthropocene since 1945 (1st ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674545038.

- ^ Daly, Herman E.; Farley, Joshua C. (2010). Ecological economics, second edition: Principles and applications. Island Press. ISBN 9781597266819.

- ^ IPBES (2019). "Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)" (PDF). Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- ^ أ ب Crist E, Kopnina H, Cafaro P, Gray J, Ripple WJ, Safina C, Davis J, DellaSala DA, Noss RF, Washington H, Rolston III H, Taylor B, Orlikowska EH, Heister A, Lynn WS, Piccolo JJ (18 November 2021). "Protecting half the planet and transforming human systems are complementary goals". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 2. 761292. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2021.761292.

- ^ أ ب ت Darimont, Chris T.; Fox, Caroline H.; Bryan, Heather M.; Reimchen, Thomas E. (21 August 2015). "The unique ecology of human predators". Science. 349 (6250): 858–860. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..858D. doi:10.1126/science.aac4249. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26293961. S2CID 4985359.

- ^ أ ب Cafaro, Philip; Hansson, Pernilla; Götmark, Frank (August 2022). "Overpopulation is a major cause of biodiversity loss and smaller human populations are necessary to preserve what is left" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 272. 109646. Bibcode:2022BCons.27209646C. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109646. ISSN 0006-3207. S2CID 250185617. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-12-08. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ^ Fricke, Evan C.; Hsieh, Chia; Middleton, Owen; Gorczynski, Daniel; Cappello, Caroline D.; Sanisidro, Oscar; Rowan, John; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Beaudrot, Lydia (August 25, 2022). "Collapse of terrestrial mammal food webs since the Late Pleistocene". Science. 377 (6609): 1008–1011. Bibcode:2022Sci...377.1008F. doi:10.1126/science.abn4012. PMID 36007038. S2CID 251843290.

Food webs underwent steep regional declines in complexity through loss of food web links after the arrival and expansion of human populations. We estimate that defaunation has caused a 53% decline in food web links globally.

- ^ Dasgupta, Partha S.; Ehrlich, Paul R. (19 April 2013). "Pervasive Externalities at the Population, Consumption, and Environment Nexus". Science. 340 (6130): 324–328. Bibcode:2013Sci...340..324D. doi:10.1126/science.1224664. PMID 23599486. S2CID 9503728. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Cincotta, Richard P.; Engelman, Robert (Spring 2000). "Biodiversity and population growth". Issues in Science and Technology. 16 (3): 80. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Maurer, Brian A. (January 1996). "Relating Human Population Growth to the Loss of Biodiversity". Biodiversity Letters. 3 (1): 1–5. doi:10.2307/2999702. JSTOR 2999702. Archived from the original on 2 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Cockburn, Harry (March 29, 2019). "Population explosion fuelling rapid reduction of wildlife on African savannah, study shows". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

Encroachment by people into one of Africa's most celebrated ecosystems is "squeezing the wildlife in its core", by damaging habitation and disrupting the migration routes of animals, a major international study has concluded.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Stokstad, Erik (5 May 2019). "Landmark analysis documents the alarming global decline of nature". Science. AAAS. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

For the first time at a global scale, the report has ranked the causes of damage. Topping the list, changes in land use—principally agriculture—that have destroyed habitat. Second, hunting and other kinds of exploitation. These are followed by climate change, pollution, and invasive species, which are being spread by trade and other activities. Climate change will likely overtake the other threats in the next decades, the authors note. Driving these threats are the growing human population, which has doubled since 1970 to 7.6 billion, and consumption. (Per capita of use of materials is up 15% over the past 5 decades.)

- ^ أ ب ت Ceballos, Gerardo; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dirzo, Rodolfo (23 May 2017). "Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines". PNAS. 114 (30): E6089–E6096. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E6089C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704949114. PMC 5544311. PMID 28696295.

Much less frequently mentioned are, however, the ultimate drivers of those immediate causes of biotic destruction, namely, human overpopulation and continued population growth, and overconsumption, especially by the rich. These drivers, all of which trace to the fiction that perpetual growth can occur on a finite planet, are themselves increasing rapidly

- ^ أ ب Wiedmann, Thomas; Lenzen, Manfred; Keyßer, Lorenz T.; Steinberger, Julia K. (2020). "Scientists' warning on affluence". Nature Communications. 11 (3107): 3107. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3107W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. PMC 7305220. PMID 32561753.

The affluent citizens of the world are responsible for most environmental impacts and are central to any future prospect of retreating to safer environmental conditions . . . It is clear that prevailing capitalist, growth-driven economic systems have not only increased affluence since World War II, but have led to enormous increases in inequality, financial instability, resource consumption and environmental pressures on vital earth support systems.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (March 2, 2023). "Overconsumption by the rich must be tackled, says acting UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice" (PDF). BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

Moreover, we have unleashed a mass extinction event, the sixth in roughly 540 million years, wherein many current life forms could be annihilated or at least committed to extinction by the end of this century.

- ^ أ ب McGrath, Matt (6 May 2019). "Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

Pushing all this forward, though, are increased demands for food from a growing global population and specifically our growing appetite for meat and fish.

- ^ أ ب Carrington, Damian (February 3, 2021). "Plant-based diets crucial to saving global wildlife, says report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ أ ب ت Machovina, B.; Feeley, K. J.; Ripple, W. J. (2015). "Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption". Science of the Total Environment. 536: 419–431. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.536..419M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.022. PMID 26231772.

- ^ أ ب Smithers, Rebecca (5 October 2017). "Vast animal-feed crops to satisfy our meat needs are destroying planet". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Boscardin, Livia (12 July 2016). "Greenwashing the Animal-Industrial Complex: Sustainable Intensification and Happy Meat". 3rd ISA Forum of Sociology, Vienna, Austria. ISAConf.confex.com. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ Elbein, Saul (December 11, 2021). "Wetlands point to extinction problems beyond climate change". The Hill. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ أ ب Wake, David B.; Vredenburg, Vance T. (2008-08-12). "Are we in the midst of the sixth mass extinction? A view from the world of amphibians". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (Suppl 1): 11466–11473. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511466W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801921105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2556420. PMID 18695221.

The possibility that a sixth mass extinction spasm is upon us has received much attention. Substantial evidence suggests that an extinction event is underway.

- ^ Wilson, Edward O. (2003). The Future of life (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780679768111.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Dirzo, Rodolfo; Young, Hillary S.; Galetti, Mauro; Ceballos, Gerardo; Isaac, Nick J. B.; Collen, Ben (2014). "Defaunation in the Anthropocene" (PDF). Science. 345 (6195): 401–406. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..401D. doi:10.1126/science.1251817. PMID 25061202. S2CID 206555761. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

In the past 500 years, humans have triggered a wave of extinction, threat, and local population declines that may be comparable in both rate and magnitude with the five previous mass extinctions of Earth's history

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805092998.

- ^ أ ب ت Williams, Mark; Zalasiewicz, Jan; Haff, P. K.; Schwägerl, Christian; Barnosky, Anthony D.; Ellis, Erle C. (2015). "The Anthropocene Biosphere". The Anthropocene Review. 2 (3): 196–219. Bibcode:2015AntRv...2..196W. doi:10.1177/2053019615591020. S2CID 7771527.

- ^ أ ب Doughty, C. E.; Wolf, A.; Field, C. B. (2010). "Biophysical feedbacks between the Pleistocene megafauna extinction and climate: The first human-induced global warming?". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (15): n/a. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3715703D. doi:10.1029/2010GL043985. S2CID 54849882.

- ^ أ ب ت Grayson, Donald K.; Meltzer, David J. (December 2012). "Clovis Hunting and Large Mammal Extinction: A Critical Review of the Evidence". Journal of World Prehistory. 16 (4): 313–359. doi:10.1023/A:1022912030020. S2CID 162794300.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Vignieri, S. (25 July 2014). "Vanishing fauna (Special issue)". Science. 345 (6195): 392–412. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..392V. doi:10.1126/science.345.6195.392. PMID 25061199.

- ^ Faith, J. Tyler; Rowan, John; Du, Andrew; Barr, W. Andrew (July 2020). "The uncertain case for human-driven extinctions prior to Homo sapiens". Quaternary Research (in الإنجليزية). 96: 88–104. Bibcode:2020QuRes..96...88F. doi:10.1017/qua.2020.51. ISSN 0033-5894.

- ^ أ ب ت Perry, George L. W.; Wheeler, Andrew B.; Wood, Jamie R.; Wilmshurst, Janet M. (2014-12-01). "A high-precision chronology for the rapid extinction of New Zealand moa (Aves, Dinornithiformes)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 105: 126–135. Bibcode:2014QSRv..105..126P. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.025.

- ^ أ ب ت Crowley, Brooke E. (2010-09-01). "A refined chronology of prehistoric Madagascar and the demise of the megafauna". Quaternary Science Reviews. Special Theme: Case Studies of Neodymium Isotopes in Paleoceanography. 29 (19–20): 2591–2603. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29.2591C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.030.

- ^ Li, Sophia (2012-09-20). "Has Plant Life Reached Its Limits?". Green Blog. Archived from the original on 2018-06-20. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ أ ب Lawton, J. H.; May, R. M. (1995). "Extinction Rates". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 9: 124–126. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1996.t01-1-9010124.x.

- ^ Lawton, J. H.; May, R. M. (1995). "Extinction Rates". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 9 (1): 124–126. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1996.t01-1-9010124.x.