ألكزاندريا، ڤرجينيا

ألكزاندريا، ڤرجينيا | |

|---|---|

| City of Alexandria | |

The George Washington Masonic National Memorial in 2015, with Washington, D.C. and Arlington in the distance | |

| الإحداثيات: 38°48′17″N 77°02′50″W / 38.80472°N 77.04722°W | |

| Country | الولايات المتحدة |

| State | Virginia |

| County | Independent city |

| Founded | 1749 |

| Incorporated (town) | 1779 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1852 |

| Incorporated (Independent city) | 1870 |

| الحكومة | |

| • النوع | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Allison Silberberg (D) |

| • Virginia Senate | Adam Ebbin (D) Richard L. Saslaw (D) George Barker (D) |

| • Delegate | Rob Krupicka (D) Charniele Herring (D) |

| • U.S. House | Don Beyer (D) |

| • U.S. Senate | Mark Warner (D) Tim Kaine (D) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 40٫1 كم² (15٫5 ميل²) |

| • البر | 38٫9 كم² (15�0 ميل²) |

| • الماء | 1٫1 كم² (0٫4 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 12 m (39 ft) |

| التعداد (2010) | |

| • الإجمالي | 139٬966 |

| • Estimate (2015) | 153٬511 |

| • الكثافة | 3٬946٫3/km2 (10٬221/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Alexandrian |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 22301 to 22315, 22320 to 22336 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 571, 703 |

| FIPS code | 51-01000[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1492456[2] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

ألكزاندريا أو الإسكندرية Alexandria is an independent city in the United States Commonwealth of ڤرجينيا. As of the 2010 census, the population was 139,966,[3] and in 2015, the population was estimated to be 153,511.[4] Located along the western bank of the Potomac River, Alexandria is approximately 7 miles (11 km) south of downtown Washington, D.C.

Like the rest of Northern Virginia, as well as Central Maryland, modern Alexandria has been influenced by its proximity to the U.S. capital. It is largely populated by professionals working in the federal civil service, in the U.S. military, or for one of the many private companies which contract to provide services to the federal government. One of Alexandria's largest employers is the U.S. Department of Defense. Another is the Institute for Defense Analyses. In 2005, the United States Patent and Trademark Office moved to Alexandria.

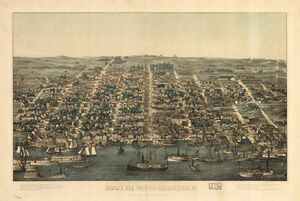

The historic center of Alexandria is known as "Old Town". With its concentration of boutiques, restaurants, antique shops and theaters, it is a major draw for all who live in Alexandria as well for visitors. Like Old Town, many Alexandria neighborhoods are pleasant for strolling, jogging, bicycling, pogo-ing, tricycling. It is the 7th largest and highest-income independent city in Virginia.

A portion of adjacent Fairfax County is named "Alexandria," but it is under the jurisdiction of Fairfax County and separate from the city; the city is sometimes referred to as the City of Alexandria to avoid confusion. In 1920, Virginia's General Assembly voted to incorporate what had been Alexandria County as Arlington County to minimize confusion.

التاريخ

التاريخ المبكر

According to archaeologists' estimates, a succession of indigenous peoples began to occupy the Chesapeake and Tidewater region about 3,000 to 10,000 years ago. Various Algonquian-speaking peoples inhabited the lands in the Potomac River drainage area since at least the early 14th century.[5]

In the summer of 1608, English settler John Smith explored the Potomac River and came into contact with the Patawomeck (loosely affiliated with the Powhatan) and Doeg tribes who lived on the Virginia side, as well as on Theodore Roosevelt Island, and the Piscataway (also known as the Conoy), who resided on the Maryland side.[6] On this visit, Smith recorded the presence of a settlement called Assaomeck near the south bank of what is now Hunting Creek.[7]

العهد الاستعماري

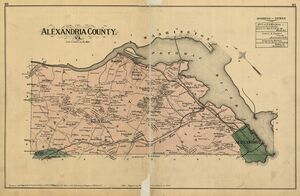

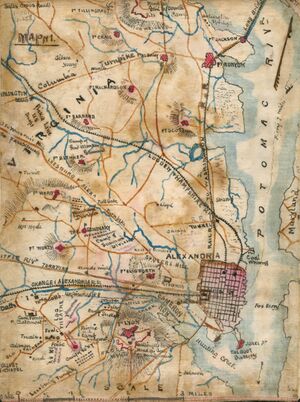

An 1878 map of Alexandria County, including what is now Arlington County and the City of Alexandria. Map includes the names of property owners at that time. City boundaries roughly correspond with Old Town. |

On October 21, 1669, a patent granted 6,000 acres (24 km2) to Robert Howsing for transporting 120 people to the Colony of Virginia.[8] That tract would later become the City of Alexandria.[8] Virginia's comprehensive Tobacco Inspection Law of 1730 mandated that all tobacco grown in the colony must be brought to locally designated public warehouses for inspection before sale. One of the sites designated for a warehouse on the upper Potomac River was at the mouth of Hunting Creek.[9] However, the ground proved to be unsuitable, and the warehouse was built half a mile up-river, where the water was deep near the shore.

Following the 1745 settlement of the Virginia's 10-year dispute with Lord Fairfax over the western boundary of the Northern Neck Proprietary, when the Privy Council in London found in favor of Lord Fairfax's expanded claim, some of the Fairfax County gentry formed the Ohio Company of Virginia. They intended to conduct trade into the interior of America, and they required a trading center near the head of navigation on the Potomac. The best location was Hunting Creek tobacco warehouse, since the deep water could easily accommodate sailing ships. Many local tobacco planters, however, wanted a new town further up Hunting Creek, away from nonproductive fields along the river.[10]

Around 1746, Captain Philip Alexander II (1704–1753) moved to what is south of present Duke Street in Alexandria. His estate, which consisted of 500 acres (2.0 km2), was bounded by Hunting Creek, Hooff's Run, the Potomac River, and approximately the line which would become Cameron Street. At the opening of Virginia's 1748–49 legislative session, there was a petition submitted in the House of Burgesses on November 1, 1748, that the "inhabitants of Fairfax (Co.) praying that a town may be established at Hunting Creek Warehouse on Potowmack River," since Hugh West was the owner of the warehouse. The petition was introduced by Lawrence Washington, the representative for Fairfax County and, more importantly, the son-in-law of William Fairfax and a founding member of the Ohio Company. To support the company's push for a town on the river, Lawrence's younger brother George Washington, an aspiring surveyor, made a sketch of the shoreline touting the advantages of the tobacco warehouse site.[11]

Since the river site was amidst his estate, Philip opposed the idea and strongly favored a site at the head of Hunting Creek (also known as Great Hunting Creek). It has been said that in order to avoid a predicament the petitioners offered to name the new town Alexandria, in honor of Philip's family. As a result, Philip and his cousin Captain John Alexander (1711–1763) gave land to assist in the development of Alexandria and are thus listed as the founders. This John was the son of Robert Alexander II (1688–1735). On May 2, 1749, the House of Burgesses approved the river location and ordered "Mr. Washington do go up with a Message to the Council and acquaint them that this House have agreed to the Amendments titled An Act for erecting a Town at Hunting Creek Warehouse, in the County of Fairfax."[12] A "Public Vendue" (auction) was advertised for July, and the county surveyor laid out street lanes and town lots. The auction was conducted on July 13–14, 1749.

Almost immediately upon establishment, the town founders called the new town "Belhaven", believed to be in honor of a Scottish patriot, John Hamilton, 2nd Lord Belhaven and Stenton, the Northern Neck tobacco trade being then dominated by Scots. The name Belhaven was used in official lotteries to raise money for a Church and Market House, but it was never approved by the legislature and fell out of favor in the mid-1750s.[13] The town of Alexandria did not become incorporated until 1779.

In 1755, General Edward Braddock organized his fatal expedition against Fort Duquesne at Carlyle House in Alexandria. In April 1755, the governors of Virginia, and the provinces of Maryland, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York met to determine upon concerted action against the French in America.[14]

In March 1785, commissioners from Virginia and Maryland met in Alexandria to discuss the commercial relations of the two states, finishing their business at Mount Vernon. The Mount Vernon Conference concluded on March 28 with an agreement for freedom of trade and freedom of navigation of the Potomac River. The Maryland legislature, in ratifying this agreement on November 22, proposed a conference among representatives from all the states to consider the adoption of definite commercial regulations. This led to the calling of the Annapolis Convention of 1786, which in turn led to the calling of the Federal Convention of 1787.[14]

In 1791, Alexandria was included in the area chosen by George Washington to become the District of Columbia.

مطلع القرن 19

In 1814, during the War of 1812, a British fleet launched a successful Raid on Alexandria, which surrendered without a fight. As agreed in the terms of surrender the British looted stores and warehouses of mainly flour, tobacco, cotton, wine, and sugar.[15] In 1823 William Holland Wilmer, Francis Scott Key, and others founded the Virginia Theological Seminary.[16] From 1828 to 1836,[17] Alexandria was home to the Franklin & Armfield Slave Market, one of the largest slave trading companies in the country. By the 1830s, they were sending more than 1,000 slaves annually from Alexandria to their Natchez, Mississippi, New Orleans, and later Texas markets to help meet the demand for slaves in Mississippi and nearby states.[18] Later owned by Price, Birch & Co., the slave pen became a jail under Union occupation.[19]

A portion of the City of Alexandria—most of the area now known as Old Town as well as the areas of the city northeast of what is now King Street—and all of today's Arlington County share the distinction of having been the portion of Virginia ceded to the U.S. Government in 1791 to help form the new District of Columbia. Over time, a movement grew to separate what was called "Alexandria County" from the District of Columbia. As competition grew with the port of Georgetown and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal fostered development on the north side of the Potomac River, Alexandria's economy stagnated; at the same time, residents had lost any representation in Congress and the right to vote and were disappointed with the negligible economic benefit (on the Alexandria side) of being part of the national capital. Alexandria still had an important port and market in the slave trade, and as talk increased of abolishing slavery in the national capital, there was concern that Alexandria's economy would suffer greatly if this step were taken. After a referendum, voters petitioned Congress and Virginia to return the portion of the District of Columbia south of the Potomac River (Alexandria County) to Virginia. On July 9, 1846, Congress retroceded Alexandria County to Virginia.[20] The City of Alexandria was re-chartered in 1852 and became independent of Alexandria County in 1870. The remaining portion of Alexandria County changed its name to Arlington County in 1920.

أواخر القرن 19

The first fatalities of the North and South in the American Civil War occurred in Alexandria. Within a month of the Battle of Fort Sumter, the Civil War's first battle, Union Army troops occupied Alexandria, landing troops at the base of King Street on the Potomac River on May 24, 1861. A few blocks up King Street from their landing site, the commander of the New York Fire Zouaves, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, sortied with a small detachment to remove a large Confederate flag displayed on the roof of the Marshall House Inn that had been visible from the White House. While descending from the roof, Ellsworth was shot dead by James W. Jackson, the hotel's proprietor. One of Ellsworth's soldiers immediately killed Jackson.[21][22] Ellsworth was publicized as a Union martyr, and the incident generated great excitement in the North, with many children being named for him.[21][22] Jackson's death defending his home caused a similar sensation in the South.[21][23]

Alexandria remained under military occupation until the end of the Civil War. Fort Ward, one of a ring of forts built by the Union army for the defense of Washington, D.C., is located inside the boundaries of present-day Alexandria.[24] There were five military prisons in the city, the largest being the Washington Street Military Prison.[25][26] After the creation by Washington of the state of West Virginia in 1863 and until the close of the war, Alexandria was the seat of the so-called Restored Government of Virginia, also known as the "Alexandria Government".[14] During the Union occupation, a recurring contention between the Alexandria citizenry and the military occupiers was the Union army's periodic insistence that church services include prayers for the President of the United States. Failure to do so resulted in incidents including the arrest of ministers in their church.

In 1861 and 1862, escaped African American slaves poured into Alexandria. Safely behind Union lines, the cities of Alexandria and Washington offered comparative freedom and employment. Alexandria became a major supply depot and transport and hospital center for the Union army.[27] Until the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863, escaped slaves legally remained the property of their owners. Therefore, they were labeled contrabands to avoid returning them to their masters. Contrabands worked for the Union army in various support roles.

After all slaves in the seceding states were liberated, even more African Americans came to Alexandria. By the fall of 1863, the population of Alexandria had exploded to 18,000 — an increase of 10,000 people in 16 months.[27]

As of ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, Alexandria County's black population was more than 8,700, or about half the total number of residents in the county. This newly enfranchised constituency provided the support necessary to elect the first black Alexandrians to the City Council and the Virginia Legislature.[28]

In the waning years of the 19th century, Alexandria suffered its two documented lynchings. The first, in 1897, was Joseph H. McCoy and the second, in 1899, was Benjamin Thomas Both were Black male teenagers accused, but never convicted, of assaulting young white girls that were known to them. They were both kidnapped from jail and hanged by mobs.[29]

القرن العشرون

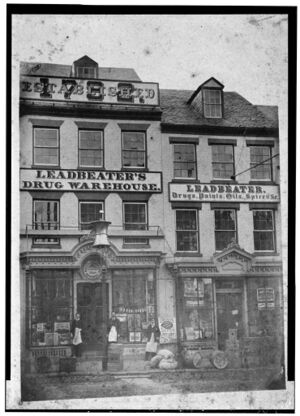

At the turn of the 20th century the most common production in the city was glass, fertilizer, beer, and leather. The glass often went into beer bottles. Much of the Virginia Glass Company effort went to supply the demands of the Robert Portner Brewing Company, until fire destroyed the St. Asaph Street plant on February 18, 1905. The Old Dominion Glass Company also had a glass works fall to fire, then built a new one. The Belle Pre Bottle Company held a monopoly on a milk bottle that they patented, yet that organization only lasted 10 years.[30] Most businesses were smaller where the business occupied the first floor of a building and the owner and family lived above.[31] Prohibition closed Portner Brewing in 1916.[31]

President Woodrow Wilson visited the Virginia Shipbuilding Corporation on May 30, 1918, to drive the first rivet into the keel of the إسإس Gunston Hall.[31] In 1930, Alexandria annexed the town adjacent to Potomac Yard incorporated in 1908 named Potomac. In 1938 the Mt. Vernon Drive-In cinema opened.[32] In 1939, the segregated public library experienced a sit-in organized by Samuel Wilbert Tucker.[33] In 1940, both the Robert Robinson Library, which is now the Alexandria Black History Museum, and the Vernon Theatre opened[34] Jim Morrison of The Doors, as well as Cass Elliot and John Phillips of The Mamas & The Papas attended the George Washington High School in the 1950s.[35]

In 1955, then-Representative and future President Gerald R. Ford and his family moved to Alexandria from Georgetown.[36] The Fords remained in their Alexandria home during Ford's tenure as Vice President (1973–1974), as the vice president did not yet have an official residence.[37] Following the resignation of Richard Nixon, Ford spent his first 10 days as President in the house before moving to the White House.[37]

In March 1959, Lieutenant Colonel William Henry Whalen, the "highest-ranking American ever recruited as a mole by the Russian Intelligence Service", provided Colonel Sergei A. Edemski three classified Army manuals in exchange for $3,500 at a shopping center parking lot within the city.[38] Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation later arrested Whalen on July 12, 1966, at his home in the city.[39] In 1961 the original Woodrow Wilson Bridge opened.[40]

In 1965, the city integrated schools.[41] In 1971, the city consolidated all high school junior and senior students into T. C. Williams High School. Freshman and sophomore students were assigned to attend either Francis C Hammond or George Washington, formerly four-year high schools, as part of a system-wide overhaul of the public school system, beginning with kindergarten classes, in an attempt to racially "balance" student population throughout the city's public schools to better reflect the city's racial makeup. The plan was known as the "K-6, 2, 2, 2 plan". Classes were broken out, beginning with kindergarten through sixth grade; then seventh through eighth; then freshman and sophomore classes; and finally junior and senior classes, with the changes including being moved to a different school building.[41] The same year that head coach Herman Boone joined the school and lead the football team to a 13–0 season, a state championship, and a national championship runner-up; the basis for the 2000 film Remember the Titans where Boone was portrayed by Denzel Washington.[42] In 1972, Clifford T. Cline purchased the 1890 Victorian house at 219 King Street and converted it into the Creole serving Two-Nineteen Restaurant.[43] In 1973, Nora Lamborne and Beverly Beidler became the first women elected to the city council.[31] In 1974, the Torpedo Factory Art Center opened.[35] In 1983, the King Street–Old Town station, Braddock Road station, and Eisenhower Avenue station opened as the Washington Metro system expanded.[40] In 1991, the Van Dorn Street station opened and Patricia Ticer became the first woman to be elected mayor.[31]

History of libraries

John Wise, a local Alexandria businessman and hotel keeper, hosted a meeting in his home in 1789 to discuss the creation of a Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge. Members include Rev. James Muir, physician Elisha Cullen Dick, and George Washington's personal attorney Charles Lee. The Society did not last for long. However, on July 24, 1794, the founders of the Society once again met at Wise's home to establish a subscription library. During the first year, one hundred nineteen men joined the circulating library which was to be called the Library Company of Alexandria. Members agreed to pay an initiation fee and annual dues. The company was chartered as a corporation in 1798 in an act passed by the General Assembly of Virginia.

Druggist Edward Stabler was elected the first librarian and the library's first location is believed to have been housed in his apothecary shop. James Kennedy was elected the second librarian, and the library moved to his residence and place of business. Kennedy sold books from his personal collection to the Library Company. Those books and other bought from two local merchants formed the foundation of the subscription library. The first catalog of the library's collection was published in 1797. The collection grew over time, bolstered in part by the fact that some members paid their dues in books. Most members were initially men, although records exist showing some women were members as early as 1798. One noted female member in 1817 was Mary L.F. Custis, wife of George Washington Parke Custis.

The catalog published in 1801 indicated a collection of 452 books, mostly on history and travel. By 1815, there were 1,022 entries in the catalog, and the collection had added more biographies, fiction, and magazines. The library was housed in several locations over the ensuing years, including the New Market House next to the City Hall, the Lyceum Company building, and Peabody Hall, which was owned by the Alexandria School Board. Raising funds for the library was a continuing challenge. In 1853, a lecture series was created to raise money. Speakers included Professor Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian, Colonel Francis H. Smith of the Virginia Military Institute, and humorist George W. Bagby.

The Civil War took its toll on the library collection. Members were able to remove some of the collection prior to the library's occupation by Union troops. The library was used as a hospital and much of the library's collection was lost during this time. After the war, the building was sold to a private owner who planned to turn the building into a private residence and asked the library to remove what was left of the collection. Funds continued to be hard to come by and in 1879, the Library Company closed. The remainder of its collection was stored in Peabody Hall.

In 1897, a group of women in Alexandria formed the Alexandria Library Association. The leaders of the group were Virginia Corse, Mrs. William B. Smoot, and Virginia Burke. They petitioned the school board to open a subscription library in Peabody Hall, using the old books stored there. Permission was given and doors to the new subscription library opened on December 1, 1897. In 1902, the library moved to the first floor of a house in the 1300 block of Prince Street while negotiations were underway for a permanent move to the Confederate Hall, located at 806 Prince Street. In May 1903, the library moved to the Confederate Hall, now known as the Robert E. Lee Camp Hall Museum, where it stayed for 34 years.

In 1936, Dr. and Mrs. Robert South Barrett presented a proposal to the Library Association. They agreed to donate a building in memory of Dr. Barrett's mother, Kate Waller Barrett, if the city would commit to running it as a public library. The city agreed and the Society of Friends offered a 99-year lease on an old Quaker graveyard located on Queen Street. The old library was closed on March 1 for the books to be packed and moved to the new library, which opened to the public in August 1937. The Alexandria Library Association became the Alexandria Library Society.

In 1939, the Barrett library was the scene of possibly the nation's first sit-in demonstrations, as Samuel Tucker, a young law school graduate from the neighborhood, and several other African American residents insisted on access to the racially segregated library where they had been banned. Tucker later became a prominent attorney in Richmond.[44][45]

In 1947, the Library Society was reconstituted and took the earlier historic name Alexandria Library Company. A lecture series was also revived. Speakers included Thomas Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone. Some of the books belonging in the original collection of the Alexandria Library Company can now be found in the Local History/Special Collections Room at the Queen Street library that still carries Mrs. Barrett's name.[46]

In 1948, Ellen Coolidge Burke became director. Burke brought bookmobile services to Alexandria, one of the first services in Virginia. She oversaw the growth of the library system by the addition of two new branch libraries. In April 1968 the Ellen Coolidge Burke Branch at 4701 Seminary Road was opened, and in December 1969 the James M. Duncan branch at 2501 Commonwealth Avenue. Burke retired in 1969.[47]

الهامش

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUSCensusEst2015 - ^ Ferguson, Alice and Henry (1960). The Piscataway Indians of Southern Maryland. Alice Ferguson Foundation. p. 11.

- ^ Humphrey, Robert L.; Chambers, Mary Elizabeth (1977). Ancient Washington: American Indian Cultures of the Potomac Valley. George Washington University.

- ^ Cressey, Pamela (6 June 1996). "Assaomeck village depended on fish". Alexandria Gazette Packet. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ^ أ ب Brockett, Franklin Longdon; Rock, George W. (1883). A Concise History of the City of Alexandria, Va: From 1669 to 1883, with a Directory of Reliable Business Houses in the City. Gazette Book and Job office. p. 140.

- ^ "Economic Aspects of Tobacco during the Colonial Period 1612–1776". Tobacco.org. Archived from the original on فبراير 22, 2012. Retrieved يناير 29, 2012.

- ^ "Discovering the Decades: 1740s | Historic Alexandria | City of Alexandria, VA". Alexandriava.gov. January 5, 2011. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ "George Washington: Surveyor and Mapmaker". Loc.gov. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- ^ Virginia. General Assembly. House of Burgesses (1909). Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, 1742–1747, 1748–1749. Colonial Press, E. Waddey Company. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ "The Scheme of a Lottery, at Belhaven, in Fairfax County: January 24, 1750/51; Virginia Gazette extracts; The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol.12 No.2 (October 1903)". Files.usgwarchives.net. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Chisholm 1911, p. 573.

- ^ "Discovering the Decades: 1810s". Alexandria Archaeology Museum. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Cromey, Robert Warren (Sep 27, 2012). Essays Irreverent. iUniverse. p. 184.

- ^ "Self-Guided Walking Tour Black Historic Sites". Alexandria Black History Museum. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Jim Barnett and H. Clark Burkett (2004). "The Forks of the Road Slave Market at Natchez". Mississippi History Now. Archived from the original on September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Photographs of African Americans During the Civil War: A List of Images in the Civil War Photograph Collection". Library of Congress. May 20, 2004. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ "Get to know D.C. – Frequently Asked Questions About Washington, D.C." History Society of Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007.

- ^ أ ب ت "Wayfinding: Marshall House". City of Alexandria, Virginia. 2018-03-28. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ أ ب (1) "The Murder of Colonel Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (232): 357–358. 1861-06-08. Retrieved 2019-01-28 – via Internet Archive.

(2) "The Murder of Ellsworth". Harper's Weekly. 5 (233): 369. 1861-06-15. Retrieved 2019-01-28 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Pfingsten, Bill (ed.). ""The Marshall House" marker". HMdb: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on يناير 26, 2019. Retrieved يناير 26, 2019.

- ^ "Fort Ward Museum". Alexandriava.gov. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ Kilian, Michael (September 28, 2003). "The uncivil war for Alexandria". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Daniel (May 11, 2017). "Alexandria cotton mill that became a Civil War torture chamber". Alexandria Times.

- ^ أ ب "Office of Historic Alexandria, Alexandria Freedmen's Cemetery: Historical Overview, April 2007, p. 2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Theismann, Jeanne (2022-09-29). "'This Soil Cries Out'". Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ Commerce: Cox, Al; Cressey, Pamela J.; Dennee, Timothy J.; Miller, T. Michael; Smith, Peter (December 13, 2015). "Discovering the Decades: 1900s". City of Alexandria. Archived from the original on March 21, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.Pulliam, Ted (2011). Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History. HPN. p. 96.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Pulliam, Ted (2011). Historic Alexandria: An Illustrated History. HPN. p. 96.

- ^ "Movie Theaters in Alexandria, VA". Los Angeles: Cinema Treasures LLC. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ Alexandria Library Sit-In: Combs, George K.; Anderson, Leslie; Downie, Julia M. (2012). Alexandria. Arcadia. p. 127."America's First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In - Determining the Facts - Reading 2: The Nation's First Sit-In". Alexandria Black History Museum. City of Alexandria. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2009."1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in". Alexandria Library. City of Alexandria. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ Robinson Library: Alexandria Historic Timeline, Virginia: Visit Alexandria, http://www.visitalexandriava.com/about-alexandria/history/timeline/, retrieved on May 21, 2015Vernon Theatre:"Movie Theaters in Alexandria, VA". Los Angeles: Cinema Treasures LLC. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ أ ب Alexandria Historic Timeline, Virginia: Visit Alexandria, http://www.visitalexandriava.com/about-alexandria/history/timeline/, retrieved on May 21, 2015

- ^ Mieczkowski, Yanek (April 22, 2005). Gerald Ford and the Challenges of the 1970s. University Press of Kentucky. p. 480.

- ^ أ ب "Gerald Ford in Alexandria". Alexandriava.gov (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- ^ Manuals: Richelson, Jeffery T. (Jul 17, 1997). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 544.Highest-ranking:Epstein, Edward Jay. "Question of the Day". Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.$3,500:

highest-ranking American ever recruited as a mole by the Russian Intelligence Service

Associated Press (March 1, 1967). "Yank Gets 20 Years For Helping Soviets". Amarillo Globe-Times. - ^ "Ex-Army Officer Accused Of Spying For Russians". Toledo Blade. July 13, 1966.

- ^ أ ب "Timeline of Alexandria History". Alexandria in the 20th Century. City of Alexandria, VA. Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2015.

- ^ أ ب Shapiro, Len; Pollin, Andy (Dec 16, 2008). The Great Book of Washington DC Sports Lists. Running. p. 304.

- ^ 1971 T. C. Williams High School football team season: Fleming, Monika S. (2013). Legendary Locals of Edgecombe and Nash Counties, North Carolina. Arcadia. p. 127.Ellington, Scott A. (Sep 1, 2008). Risking Truth: Reshaping the World through Prayers of Lament. Wipf and Stock. p. 214.Shapiro, Len; Pollin, Andy (Dec 16, 2008). The Great Book of Washington DC Sports Lists. Running. p. 304.

- ^ Nunley, Debbie; Elliott, Karen Jane (2004). A Taste of Virginia History: A Guide to Historic Eateries and Their Recipes. John F. Blair. p. 294.

- ^ "1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in". Jim Crow Lived Here. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ^ "Alexandria Historical Society – Alexandria's History". Alexandriahistoricalsociety.wildapricot.org. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ^ Seale, William. The Alexandria Library Company. Alexandria, Virginia: Alexandria Library, 2007.

- ^ "Ellen Coolidge Burke". Alexandria Libraries. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

وصلات خارجية

- City of Alexandria official website

- Official Alexandria visitors' website

- Alexandria Economic Development Partnership

- City of Alexandria at the Wayback Machine (archived أبريل 13, 1997)

|

Arlington County |

| ||

| District of Columbia | Fairfax County | |||

| Fairfax County |

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Articles with dead external links from January 2012

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- صفحات تستخدم جدول مستوطنة بقائمة محتملة لمفاتيح الهاتف

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Populated places established in 1695

- ألكزاندريا، ڤرجينيا

- مدن ڤرجينيا

- History of the District of Columbia

- Washington metropolitan area

- Virginia populated places on the Potomac River

- Art gallery districts

- 1695 establishments in Virginia

- Cities in the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area