سمسون

سمسون | |

|---|---|

مع عقارب الساعة من أعلى اليمين: Samsunum-1 ship and coast, Statue of Honor, Atatürk Culture Centre, Bandırma Ferry and National Struggle Park Open Air Museum, Saathane Square, Store 55 | |

| الإحداثيات: 41°17′25″N 36°20′01″E / 41.29028°N 36.33361°E | |

| دولة | |

| المنطقة | البحر الأسود |

| المحافظة | سمسون |

| الأحياء | |

| الحكومة | |

| • Mayor | Mustafa Demir (AK Party) |

| المساحة | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | 1٬055 كم² (407 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 4 m (13 ft) |

| التعداد (2021) | |

| • Metropolitan municipality | 1٬356٬079 |

| • الكثافة | 573/km2 (1٬480/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 710٬000 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (توقيت غرب اوروبا) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (توقيت غرب اوروبا الصيفي) |

| Postal code | 55 |

| مفتاح الهاتف | (+90) 362 |

| Licence plate | 55 |

| Climate | Cfa |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.samsun.bel.tr www.samsun.gov.tr |

سمسون Samsun، وتاريخياً كانت تُعرف بإسم Sampsounta (باليونانية: Σαμψούντα) و Amisos (اليونانية القديمة: Ἀμισός)، هي مدينة تقع في شمال تركيا, على شاطئ البحر الأسود. ويصل عدد سكانها إلى 700,000 نسمة.[1] وهي عاصمة محافظة سمسون، التي يبلغ عدد سكانها 1,350,000 نسمة. وتعتبر من مدينة الموانئ الهامة في تركيا. The city is home to Ondokuz Mayıs University, several hospitals, three large shopping malls, Samsunspor football club, an opera house and a large and modern manufacturing district. A former Greek settlement,[2][3] the city is best known as the place where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk began the Turkish War of Independence in 1919.[4]

الاسم

The present name of the city is believed to have come from its former Greek name of Amisós (Αμισός) by a reinterpretation of eís Amisón (meaning "to Amisós") and ounta (Greek suffix for place names) to [eí]s Am[p]s-únta (Σαμψούντα: Sampsúnta) and then Samsun[5] (تُنطق [samsun]).

The early Greek historian Hecataeus wrote that Amisos was formerly called Enete, the place mentioned in Homer's Iliad. In Book II, Homer says that the ἐνετοί (Enetoi) inhabited Paphlagonia on the southern coast of the Black Sea in the time of the Trojan War (c. 1200 BC). The Paphlagonians are listed among the allies of the Trojans in the war, where their king Pylaemenes and his son Harpalion perished.[6] Strabo mentioned that the inhabitants had disappeared by his time.[7]

Samsun has also been known as Peiraieos by Athenian settlers and even briefly as Pompeiopolis by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus.[8]

The city was called Simisso by the Genoese. It was during the Ottoman Empire, that its present name was written as تركية عثمانية: صامسون (Ṣāmsūn). The city has been known as Samsun since the formation of the Turkey in 1923.

التاريخ

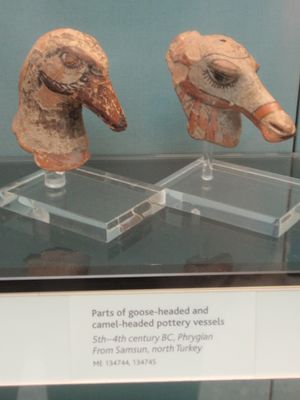

أغراض من العصر الحجري الحديث في كهوف تكهكوي يمكن مشاهدتها في متحف آثار سمسون.

The earliest layer excavated of the höyük of Dündartepe revealed a Chalcolithic settlement. Early Bronze Age and Hittite settlements were also found there[9] and at Tekkeköy.

Samsun (then known as Amisos, Greek Αμισός, alternative spelling Amisus) was settled in about 760–750 BC by Ionians from Miletus,[10] who established a flourishing trade relationship with the ancient peoples of Anatolia. The city's ideal combination of fertile ground and shallow waters attracted numerous traders.[11]

Amisus was settled by the Ionian Milesians in the 6th century BC,[2] it is believed that there was significant Greek activity along the coast of the Black Sea, although the archaeological evidence for this is very fragmentary.[12] The only archaeological evidence we have as early as the 6th century is a fragment of Wild Goat style Greek pottery, in the Louvre.[13]

The city was captured by the Persians in 550 BC and became part of Cappadocia (satrapy).[8] In the 5th century BC, Amisus became a free state and one of the members of the Delian League led by the Athenians;[14] it was then renamed Peiraeus under Pericles.[15] Starting the 3rd century BC the city came under the control of Mithridates I, later founder of the Kingdom of Pontus. The Amisos treasure may have belonged to one of the kings. Tumuli, containing tombs dated between 300 BC and 30 BC, can be seen at Amisos Hill but unfortunately Toraman Tepe was mostly flattened during construction of the 20th century radar base.[16]

The Romans conquered Amisus in 71 BC during the Third Mithridatic War.[17] and Amisus became part of Bithynia et Pontus province. Around 46 BC, during the reign of Julius Caesar, Amisus became the capital of Roman Pontus.[2] From the period of the Second Triumvirate up to Nero, Pontus was ruled by several client kings, as well as one client queen, Pythodorida of Pontus, a granddaughter of Marcus Antonius. From 62 CE it was directly ruled by Roman governors, most famously by Trajan's appointee Pliny. Pliny the Younger's address to the Emperor Trajan in the 1st century CE "By your indulgence, sir, they have the benefit of their own laws," is interpreted by John Boyle Orrery to indicate that the freedoms won for those in Pontus by the Romans was not pure freedom and depended on the generosity of the Roman emperor.[18]

The estimated population of the city around 150 AD is between 20,000 and 25,000 people, classifying it as a relatively large city for that time.[19] The city functioned as the commercial capital for the province of Pontus; beating its rival Sinope (now Sinop) due to its position at the head of the trans-Anatolia highway.[14]

In Late Antiquity, the city became part of the Dioecesis Pontica within the eastern Roman Empire; later still it was part of the Armeniac Theme.[20]

قلعة سمسون was built on the seaside in 1192, it was demolished between 1909 and 1918.

المسيحية المبكرة

Though the roots of the city are Hellenistic,[2] it was also one of the centers of an early Christian congregation.[2] Its function as a commercial metropolis in northern Asia Minor was a contributing factor to enable the spread of Christian influence. As a large port city – the commercial capital of Pontus [21] – travel to and from Christian hotbeds like Jerusalem was not uncommon.[22] According to Josephus, there was large Jewish diaspora in Asia Minor.[23] Given that the early evangelist Christians focused on Jewish diaspora communities, and that the Jewish diaspora in Amisus was a geographically accessible group with a mixed heritage group, it is not surprising that Amisus would be an appealing site for evangelist work. The author of 1 Peter 1:1 addresses the Jewish diaspora of the province of Pontus, along with four other provinces: "Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, To God's elect, exiles scattered throughout the provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia." (Peter 1:1) As Amisus would have been the largest commercial port-city in the province, it is believed certain that the spread of Christianity in the region would have begun there.[23] In the 1st century Pliny the Younger documents accounts of Christians in and around the cities of Pontus.[24] His accounts center on his conflicts with the Christians when he served under the Emperor Trajan and describe early Christian communities, his condemnation of their refusal to renounce their religion, but also describes his tolerance for some Christian practices like Christian charitable societies.[25] Many great early Christian figures had connections to Amisus, including Caesarea Mazaca, Gregory the Illuminator (raised as a Christian from 257 CE when he was brought to Amisus) and Basil the Great (Bishop of the city 330–379 CE).[26]

Christian bishops of Amisus include Antonius, who took part in the Council of Chalcedon in 451; Erythraeus, a signatory of the letter that the bishops of Helenopontus wrote to Emperor Leo I the Thracian after the killing of Patriarch Proterius of Alexandria; the late 6th-century bishop Florus, venerated as a saint in the Greek menologion; and Tiberius, who attended the Third Council of Constantinople (680), Leo, the Second Council of Nicaea (787), and Basilius, the Council of Constantinople of 879. The diocese is no longer mentioned in the Greek Notitiae Episcopatuum after the 15th century and thereafter the city was considered part of the see of Amasea. However, some Greek bishops of the 18th and 19th centuries bore the title of Amisus as titular bishops.[27] In the 13th century the Franciscans had a convent at Amisus, which became a Latin bishopric some time before 1345, when its bishop Paulus was transferred to the recently conquered city of Smyrna and was replaced by the Dominican Benedict, who was followed by an Italian Armenian called Thomas.[28] No longer a residential diocese, it is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[29]

تاريخ العصور الوسطى

Samsun was part of the Seljuk Empire,[30] the Sultanate of Rum, the Empire of Trebizond, and was one of the Genoese colonies. After the breakup of the Seljuk Empire into small principalities (beyliks) in the late 13th century, the city was ruled by one of them, the Isfendiyarids. It was captured from the Isfendiyarids at the end of the 14th century by the rival Ottoman beylik (later the Ottoman Empire) under sultan Bayezid I, but was lost again shortly afterwards.

The Ottomans permanently conquered the town in the weeks following 11 August 1420.[31]

In the later Ottoman period, it became part of the Sanjak of Canik (تركية: Canik Sancağı), which was at first part of the Rûm Eyalet. The land around the town mainly produced tobacco, with its own type being grown in Samsun, the Samsun-Bafra, which the British described as having "small but very aromatic leaves", and commanding a "high price."[32] The town was connected to the railway system in the second half of the 19th century, and tobacco trade boomed. There was a British consulate in the town from 1837 to 1863.[33]

Previously, the last Armenian Zoroastrians, the Arewordik, or children of the sun, lived in Samsun.

التاريخ الحديث

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk established the Turkish national movement against the Allies in Samsun on May 19, 1919, the date which traditionally marks the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence. Atatürk, appointed by the Ottoman government as Inspector of the Ninth Army Troops Inspectorate of the Empire in eastern Anatolia, left Constantinople aboard the now-famous SS Bandırma on May 16 for Samsun. Instead of obeying the orders of the Ottoman government, then under the control of the occupying Allies, he and a number of colleagues declared the beginning of the Turkish national movement. The Allies claimed that the Greek population of Samsun was subject looting by Turkish irregular groups, as noted by representatives of the American Near East Relief, an Allied organization.[34] The Turkish National Movement became alarmed due to the presence of Greek warships in the vicinity of Samsun and undertook the deportation which entailed the deportation of 21,000 local Greeks to the interior of Anatolia.[3] Later, in early June 1922, the city was bombarded by the Allied navy, consisting of American and Greek warships. The Allied bombardment against the Turks was a strategic failure. By 1920, Samsun's population totaled about 36,000, though this figure declined due to the impacts of war and deportations.[35]

After the establishment of the Republic, Samsun was declared a province with five districts Bafra, Çarşamba, Havza, Terme and Vezirköprü.[36] Samsun added additional districts in later years. In 1928, Ladik was established as a district. In 1934, district was Kavak was established followed by Alaçam in 1944 which brought the number of districts in Samsun Province to eight.[37][38][39] With the law number 3392 adopted on 19 June 1983 Salıpazarı, Asarcık, Ondokuzmayıs and Tekkeköy districts were established.[40] With the law number 3644 adopted on 9 May 1990, Ayvacık and Yakakent two more districts were established.[41] Samsun entered into a period of economic and population recovery in the years after the establishment of the Republic and quickly restored its status as a vital Black Sea port for Turkey.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Reconstruction of Samsun began quickly after the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. In 1929, the region's first electric power plant began operations. Railway access to the city was established in the early 1950s with service to Sivas and Ankara. Major investments in the regions road network were made beginning in the 1960s.[42][43][44] In 1975, per law No. 1873, Ondokuz Mayıs University was established in neighboring Atakum. The construction of the university was a major development to the region, bringing a highly regarded and well-funded educational institution and state hospital to Samsun. The region was connect by air in 1998 with the construction of Samsun-Çarşamba Airport 23 km east of the city center. The airport is primarily serviced by Turkish Airlines with service to Istanbul Airport and Ankara Esenboğa Airport but also has international service to Germany and Iraq. In 2008, the Metropolitan Municipality opened the 36.5 km Samsun Tram network which connects Ondokuz Mayıs University to Samsun Stadium.

In 1993, Samsun was established as a metropolitan municipality by decree of the national government in Ankara. The decree further enhanced Samsun's status as one of Turkey's largest and most important cities.[45] As Samsun grew, as did its environs. Neighboring Atakum, a suburb to the west of the city center was established in 2008 with the merger of Atakent, Kurupelit, Altınkum, Çatalçam and Taflan towns into one municipality. Atakum in recent years has become a bedroom community to Samsun and home to much of the region's professional class.

Multiple other large developments have further established Samsun as a major urban center. In 2013, Piazza Samsun a 160 store shopping mall, the largest in the Central Black Sea region, opened in the city center. The opening of the mall was followed by the construction of 115 m tall Sheraton Hotel Samsun. Now the second tallest building in the region, the hotel at the time was the first building in Samsun's history to stand more than 100 m. In 2017, Samsunspor opened a new 30,000 person stadium in Tekkeköy. Gökdelen Towers is now the tallest building in the Samsun region and representative of a recent trend towards high-rise residential housing.

Under the leadership of Metropolitan Mayor Mustafa Demir, the Samsun regional government has undertaken several major transportation and housing development projects in the city center. Projects include the restoration of the Mert River, the construction of the new National Garden, the restoration of Tarihi Şifa Hamamı and the construction of Samsun Saathane Square.[46]

الجغرافيا

Samsun is a long city which extends along the coast between two river deltas which jut into the Black Sea. It is located at the end of an ancient route from Cappadocia: the Amisos of antiquity lay on the headland northwest of the modern city center.

The city is growing fast: land has been reclaimed from the sea and many more apartment blocks and shopping malls are currently being built. Industry is tending to move (or be moved) east, further away from the city center and towards the airport.

الأنهار

Terme river, Yeşilırmak, Aptal river, Mert river, Kürtün river, Kızılırmak [47]

البحيرات

المناخ

تتميز سمسون بمناخ رطب, معتدل, بحري مع شتاء بارد وصيف حار ونسبة عالية لسقوط الأمطار طوال العام.

| أخفClimate data for سمسون | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

25 (77) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

37 (99) |

35 (95) |

39 (102) |

39 (102) |

34 (93) |

35 (95) |

32 (90) |

24 (75) |

39 (102) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10 (50) |

10.7 (51.3) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26 (79) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.8 (64.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.2 (59.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9 (48) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7 (19) |

−7 (19) |

−7 (19) |

−2 (28) |

2 (36) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

3 (37) |

−3 (27) |

−5 (23) |

−7 (19) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 74 (2.9) |

66 (2.6) |

69 (2.7) |

58 (2.3) |

46 (1.8) |

38 (1.5) |

38 (1.5) |

33 (1.3) |

61 (2.4) |

81 (3.2) |

89 (3.5) |

86 (3.4) |

739 (29.1) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 92 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68 | 72 | 77 | 80 | 82 | 78 | 74 | 74 | 75 | 72 | 71 | 69 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 93 | 84 | 124 | 150 | 217 | 270 | 310 | 279 | 210 | 155 | 120 | 93 | 2٬105 |

| Source 1: BBC Weather[48] for record temperatures, precipitation, rainy days, sunshine and humidity | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: = Climate-Data.org[49] for average temperatures | |||||||||||||

الاقتصاد

تعتبر سمسون مركز تجاري هام ومن أهم الموانئ الساحلية على البحر الأسود. وهي واحدة من المراكز الرئيسية لإنتاج التبغ في تركيا.[50] with a cluster of medical industries.[51]

الموانئ وبناء السفن

Samsun is a port city. In the early 20th century, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey funded the building of a harbor. Before the building of the harbor, ships had to anchor to deliver goods, approximately 1 mile or more from shore. Trade and transportation was focused around a road to and from Sivas.[35] The privately operated port fronting the city centre handles freight, including RORO ferries to Novorossiysk, whereas fishing boats land their catches in a separate harbour slightly further east. A ship building yard is under construction at the eastern city limit. Road and rail freight connections with central Anatolia can be used to send inland both the agricultural produce of the surrounding well rained upon and fertile land, and also imports from overseas.

واردات الفحم من الدونباس

Donbas anthracite, imported via the Russian ports of Azov and Taganrog, is said to be illegally exported Ukrainian coal.[52] In 2019 some crew were rescued but 6 died after a ship sank in the Black Sea.[53]

التصنيع والصناعات الغذائية

There is a light industrial zone between the city and the airport. The main manufactured products are medical devices and products, furniture (wood is imported across the Black Sea), tobacco products (although tobacco farming is now limited by the government), chemicals and automobile spare parts.

Flour mills import wheat from Ukraine and export some of the flour.

الحكم المحلي والخدمات

Provincial government and services (e.g. courts, prisons and hospitals) support the surrounding region. Agricultural research establishments support provincial agriculture and food processing.

التسوق

Most of the many new shopping malls are purpose built, but the former tobacco factory in the city center has been converted into a mall. Samsun's largest mall is the Piazza Samsun.

السياحة

السياحة الطبيعية

Samsun has one of the longest coastlines of the Black Sea Region and this strip stretches from Canik until May 19.[54] 90% of this 35 km long coastline consists of fine sandy beaches suitable for swimming, and alternative sports such as surfing, jet skiing and sailing can be practiced besides swimming. There are a total of 39 beaches in Samsun, with the highest number of beaches in Atakum with 19 of them.[55] After Atakum, Alaçam and Çarşamba come with three beaches each. Bafra, Ilkadım and May 19 each have two beaches, and Canik also has one beach. There are no beaches in Asarcık, Ayvacık, Havza, Kavak and Ladik. As of August 2018, all of the beaches measured by the Environmental Health Department are classified as very clean. In addition, 13 beaches, 10 of which are in Atakum, are awarded the Blue Flag beach.[56]

In Samsun, where activities for winter tourism can be carried out in addition to beach tourism, Akdağ Winter Sports and Ski Center, especially in Ladik, is the most important investment in this area with its 1675 m ski track and 1300 m chair lift, attracting tourists from the surrounding cities.[57][58] Akdağ also stands out as a paragliding, mountaineering and highland tourism center together with Kocadağ; Nebiyan Mountain is visited by mountaineers, and Kunduz Mountains are visited by transhumance.[59][60][61] In addition to natural areas such as Asarağaç Hill, Gölalan Waterfalls and Kabaceviz Waterfall, Çamgölü, Sarıgazel, Vezirköprü nature parks and Çakkır and Hasköy recreation areas have also been brought into tourism in recent years.[62][63][64][65][66] The Çarşamba Plain and the Galeriç Floodplain, especially the Kızılırmak Delta, the region, which was included in the World Heritage list in 2016, is frequently visited by bird watchers.[67][68] May 25 Thermal Tourism Center in Havza, which has been given the status of a tourism center, is the most important health tourism point in Samsun, and the thermal springs in Havza and Ladik are also among the tourism centers of the city.[69] The waters coming out of the hot springs, which are visited by 200 thousand people a year, have been used in the treatment of diseases such as rheumatic diseases, gynecological diseases, nervous diseases, joint diseases and calcification for two thousand years.[70][71]

التعليم

مزارات

- Kultur Sarayi (Palace of Culture). Concerts and other performances are held at the Kultur Sarayi, which is shaped much like a ski jump.

- Archaeological and Atatürk Museum. The archaeological part of the museum displays ancient artifacts found in the Samsun area. The Atatürk section includes photographs of his life and some personal belongings. The museum is open from 8:30 till 12:00 and from 14:00 till 17:00.

- The Russian Market (Rus Pazari).

- Statue of Atatürk. By Austrian sculptor Heinz Kriphel, from 1928 to 1931.

- Atatürk (Gazi) Museum. It houses Atatürk's bedroom, his study and conference room as well some personal belongings.

- Pazar Mosque, Samsun's oldest surviving building, a mosque built by the Ilhanid Mongols in the 13th century.

- Karadağ Geçidi (Karadag Pass) (at an altitude of 940 metres). The landscape, on the way to Amasya.

مدن شقيقة

Samsun is twinned with:

North Little Rock, Arkansas, الولايات المتحدة (2006)

North Little Rock, Arkansas, الولايات المتحدة (2006) Gorgan, إيران (2006)

Gorgan, إيران (2006) İskele، شمال قبرص (2006)[72]

İskele، شمال قبرص (2006)[72] نوڤوروسييسك، روسيا (2007)

نوڤوروسييسك، روسيا (2007) دار السلام، تنزانيا (2007)

دار السلام، تنزانيا (2007) كالمار، السويد (2008)

كالمار، السويد (2008) بوردو، فرنسا (2010)

بوردو، فرنسا (2010) كيل، ألمانيا (2010)

كيل، ألمانيا (2010) برتشكو، البوسنة والهرسك (2012)

برتشكو، البوسنة والهرسك (2012) بنزرت، تونس

بنزرت، تونس دونيتسك، أوكرانيا

دونيتسك، أوكرانيا أكرا، غانا

أكرا، غانا بيشكك، قيرغيزستان [73]

بيشكك، قيرغيزستان [73]

مشاهير سمسون

- مصطفى داغستانلي - two times Olympic gold medalist sports wrestler

- Yaşar Doğu - Olympic gold medalist sports wrestler

- Orhan Gencebay - musician

- فرحان شنسوي - كاتب, ممثل ومخرج

- Tanju Çolak - soccer player/striker, who was the top scorer in Europe in 1987 and 3rd scorer in 1986

- Yıldıray Çınar - musician

- Neyzen Tevfik – poet, satirist, and ney player

- Ece Erken – TV-hostess and actress

انظر أيضا

المصادر

- ^ "İlçe ilçe nüfus istatistikleri" [County district population statistics]. www.haberturk.com (in Turkish). 2021-02-05. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 3.

- ^ أ ب Bartrop, Paul R. (2014). Encountering Genocide: Personal Accounts from Victims, Perpetrators, and Witnesses. ABC-CLIO. p. 64. ISBN 9781610693318.

- ^ Özgören, Aydın (2019). La question du Pont-Euxin. Türk Tarih Kurumu. p. 135. ISBN 978-975-16-3633-1.

- ^ Özhan Öztürk. Karadeniz: Ansiklopedik Sözlük (Blacksea: Encyclopedic Dictionary) Archived 13 مايو 2008 at the Wayback Machine. 2 Cilt (2 Volumes). Heyamola Publishing. Istanbul. 2005 ISBN 975-6121-00-9

- ^ Homer, Iliad; online version at classics.mit.edu, accessed on 2009-08-18. Book II: "The Paphlagonians were commanded by stout-hearted Pylaemanes from Enetae, where the mules run wild in herds. These were they that held Cytorus and the country round Sesamus, with the cities by the river Parthenius, Cromna, Aegialus, and lofty Erithini."

- ^ Strab. 12.3 "Tieium is a town that has nothing worthy of mention except that Philetaerus, the founder of the family of Attalic Kings, was from there. Then comes the Parthenius River, which flows through flowery districts and on this account came by its name; it has its sources in Paphlagonia itself. And then comes Paphlagonia and the Eneti. Writers question whom the poet means by 'the Eneti,' when he says, 'And the rugged heart of Pylaemenes led the Paphlagonians, from the land of the Eneti, whence the breed of wild mules; for at the present time, they say, there are no Eneti to be seen in Paphlagonia, though some say that there is a village on the Aegialus ten schoeni distant from Amastris.' But Zenodotus writes 'from Enete,' and says that Homer clearly indicates the Amisus of today. And others say that a tribe called Eneti, bordering on the Cappadocians, made an expedition with the Cimmerians and then were driven out to the Adriatic Sea. But the thing upon which there is general agreement is, that the Eneti, to whom Pylaemenes belonged, were the most notable tribe of the Paphlagonians, and that, furthermore, these made the expedition with him in very great numbers, but, losing their leader, crossed over to Thrace after the capture of Troy, and on their wanderings went to the Enetian country, as it is now called. According to some writers, Antenor and his children took part in this expedition and settled at the recess of the Adriatic, as mentioned by me in my account of Italy. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that it was on this account that the Eneti disappeared and are not to be seen in Paphlagonia."

- ^ أ ب "Samsun Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::." Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::." Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Getzel M. (1995). "The Hellenistic Settlements in Europe, the Islands, and Asia Minor". Berkeley and Los Angeles: California: University of California Press. p. 384.

- ^ Topalidis, S. "Formation of the First Greek Settlements in the Pontos". Pontos World. Pontosworld.com. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Tsetskhladze, G.R. (1998 ) "The Greek Colonisation of the Black Sea Area: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology". Stuttgart: F. Steiner. p. 19.; Louvre page Archived 23 مايو 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ أ ب Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 4.

- ^ Jones, A.H.M (1937). "The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces". Oxford: The Clarendon Press. p. 149.

- ^ "ESKİ SAMSUN' DA (AMİSOS) AYDINLANAN TARİH". Archived from the original on 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Antik Amisos Kenti". Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- ^ Orrery, J. B. (1752). "The Letters of Pliny the Younger: With Observations on Each Letter; and an Essay on Pliny's Life, Addressed to Charles Lord Boyle". The 3rd ed. London: Printed by James Bettenham, for Paul Vaillant. p. 407.

- ^ Mitchell, S. (1995). "Anatolia: Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor". Journal of Roman Studies, 85. pp. 301–302.

- ^ Giftopoulou Sofia (2003-03-17). "Amisos (Byzantium)". Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor. Translated by Koutras Nikolaos. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ^ Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. (2013). "Roads to Pontus, Royal and Roman." The Journal of Hellenic Studies (Vol. 21). London: Forgotten Books. (Original work published pre-1945, year unknown) p. 105-6.

- ^ Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 2.

- ^ أ ب Schalit, A. "Asia Minor." Encyclopedia Judaica. Accessed 11 March 2015.

- ^ "Pliny and Trajan on the Christians." Pliny and Trajan on the Christians. Accessed 7 April 2015.

- ^ Alikin, V. A. (2010). 'Chapter 7.' In The Earliest History of the Christian Gathering: Origin, Development and Content of the Christian Gathering in the First to Third Centuries. Leiden: Brill. p. 270.

- ^ Wilson, M. W. "Cities of God in Northern Asia Minor: Using Stark's Social Theories to Reconstruct Peter's Communities". Verbum et Ecclesia 32 (1). p. 7.

- ^ Siméon Vailhé, v. Amisus, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques Archived 9 نوفمبر 2016 at the Wayback Machine, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 1289–1290]

- ^ Jean Richard, La Papauté et les missions d'Orient au Moyen Age (XIII-XV siècles), École Française de Rome, 1977, pp. 170–171 and 235–236

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 831

- ^ "File:Anatolia 1097 it.svg". 17 August 2008. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Zehiroğlu, A.M. (2018) "Trabzon İmparatorluğu" vol.III pp.150–156 ISBN 978-6058103207

- ^ Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 61. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Foreign Office: Consulate, Samsun, Ottoman Empire: Entry Books and Registers of Correspondence". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Prott, Volker (2016). The Politics of Self-Determination: Remaking Territories and National Identities in Europe, 1917–1923. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191083556.

They lotted and burned the houses of the Greeks... In early June, Hosford continued, Samsun faced the same threat of looting, massacres and deportation... Osman Aga's troops could not operate freely in Samsoun as they did later in Marsovan or had done before in the district of Bafra

- ^ أ ب Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 54. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ "Provincial and District Establishment Dates" (PDF). General Directorate of Provincial Administration. p. 72. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ قالب:Cite law

- ^ قالب:Cite law

- ^ قالب:Cite law

- ^ قالب:Cite law

- ^ قالب:Cite law

- ^ Özdemir, Naziye (2011). Historical development of electricity in Turkey (1900- 1938) (Master). Ankara: Ankara University. p. 123.

- ^ "Some important events about Samsun in the Republican era" (PDF). Samsun Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "Natural gas in Samsun hk". SAMGAZ. 8 August 2006. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ قالب:Cite law

- ^ "SAMSUN'DA TARİHİ PROJE | Yeni Günde Haber | Güncel Son Dakika Haberler". 15 December 2020.

- ^ Samsun

- ^ "BBC Weather - Samsun". BBC Weather. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةClimate-Data.org - ^ "..:: REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM ::." Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "2023 Export Target 5 Billion Dollars". 21 January 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Russia's Hybrid Strategy in the Sea of Azov: Divide and Antagonize (Part Two)". Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 16 Issue: 18. Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ "Cargo ship sinks off Turkey's Black Sea coast; 6 dead". Associated Press. 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Sağlık Bakanlığı - Halk Sağlığı Genel Müdürlüğü - Yüzme Suyu Takip Sistemi". Archived from the original on 11 June 2018.

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Akdağ'ın yılbaşı umudu".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Samsunda Turizim Alternatifleri | T.C. Samsun Valiliði | www.samsun.gov.tr". 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Samsunda Turizim Alternatifleri | T.C. Samsun Valiliði | www.samsun.gov.tr". 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ "Kabaceviz Şelaleleri'nde görsel şölen".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Kızılırmak Delta Wetland and Bird Sanctuary".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ Yenilenebilir enerji raporu (in Turkish) Archived 19 ديسمبر 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Archive.md".

- ^ "Samsun – Twin Towns". Samsun-City.sk. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- ^ "BISHKEK, KYRGYZSTAN". Samsun Metropolitan Municipality. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing التركية العثماثية (1500-1928)-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- محافظة سمسون

- مدن تركيا

- منطقة البحر الأسود

- تجمعات سكنية تأسست في القرن ق.م.

- موانئ في تركيا

- حرب الإستقلال التركية

- إنتاج تبغ تركي

- مواقع يونانية قديمة في تركيا