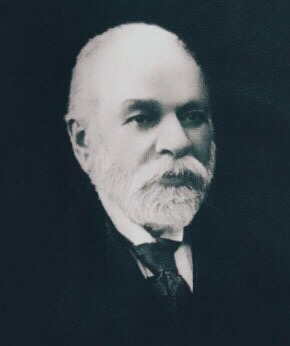

إسماعيل كمال

| Ismail Qemali | |

|---|---|

| |

| رأس دولة ألبانيا الأول | |

| في المنصب 29 نوفمبر 1912 – 22 يناير 1914 | |

| سبقه | إعلان الاستقلال |

| خلفه | Prince William of Wied |

| 1st رئيس وزراء ألبانيا | |

| في المنصب 29 نوفمبر 1912 – 22 يناير 1914 | |

| سبقه | إعلان الاستقلال |

| خلفه | فيضي بي عليزوتي |

| وزير الشئون الخارجية الأول | |

| في المنصب 4 ديسمبر 1912 – June 1913 | |

| سبقه | لا أحد |

| خلفه | مفيد ليبوهوڤا |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | 16 يناير 1844 أڤلونيا، الدولة العثمانية (اليوم: ڤلورة، جمهورية ألبانيا) |

| توفي | 24 يناير 1919 (aged 75) پرودجا، مملكة إيطاليا (اليوم: الجمهورية الإيطالية) |

| المهنة | Politics , Writer |

| الدين | الإسلام، الطريقة البكتاشية |

إسماعيل كمال بيْ ڤلورة (listen ؛ بالتركية أڤلونيالي إسماعيل كمال بـِيْ؛ 16 يناير 1844 – 24 يناير 1919) ويشيع الإشارة إليه بالتهجي Ismail Qemali كان زعيماً للحركة الوطنية الألبانية. As founder of Independent Albania he served as its first head of state and president of the provisional government until January 1914 when he was forced to step aside by the International Commission of Control established by the six القوى العظمى.[1]

سيرته

Qemali was born to a noble family in Vlorë. Having finished the primary education in his hometown, and the high school Zosimea in Janina, in 1859 he moved to Constantinople where he embarked on a career as an Ottoman civil servant, being identified with the liberal reform wing of the service under Midhat Pasha, and was governor of several towns in the Balkans. During these years he took part in efforts for the standardization of the Albanian alphabet and the establishment of an Albanian cultural association.

By 1877, Ismail seemed to be on the brink of important functions in the Ottoman administration, but when Sultan Abdulhamid II dismissed Midhat as prime minister, Ismail Qemali was sent into exile in western Anatolia, though the Sultan later recalled him and made him governor of Beirut. However, his liberal policy recommendations caused him to fall out of favour with the Sultan again, and in May 1900 Ismail Qemali boarded the British ambassador's yacht and claimed asylum. He was conveyed out of Turkey and for the next eight years lived in exile, working both to promote constitutional rule in the Ottoman Empire and to advance the Albanian national cause within it.

In January 1907 a secret agreement was signed between Qemali, a leader of the then Albanian national movement and the Greek government which concerned the possibility of an alliance against the Ottoman Empire. The two sides agreed that the future Greek-Albanian boundary should be located on the Acroceraunian Mountains with no Albanian armed activity in the area in exchange for Greek backing of Albanian independence.[2][3] Qemali's reasons for closer ties with Greece during this time was to thwart Bulgarian ambitions in the wider Balkans region and gain support for Albanian independence.[4]

After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, he became a deputy in the restored Ottoman Parliament, working with liberal politicians and the British. In 1909, during a rising against the Young Turks, he was briefly made President of the Ottoman National Assembly but was forced to leave Constantinople forever a day or two later. Thereafter his political career concentrated solely on Albanian nationalism. The Athens embassy of the Ottoman Empire reported that Qemali negotiated with organization financed by wealthy Tosks and Greece about forging a union.[5]

During the Albanian Revolt of 1911 he joined the leaders of the revolt at meeting in a village in Montenegro (Gerče) on 23 June and together they draw up "Gerče Memorandum" (sometimes referred to as "Red Book" because of the color of its covers[6] ) which addressed their requests both to Ottoman Empire and Europe (in particular to the Great Britain).[7]

He was a principal figure in the Albanian Declaration of Independence and the formation of the independent Albania on 28 November 1912. This signaled the end of almost 500 years of Ottoman rule in Albania. Together with Luigj Gurakuqi, he raised the flag on the balcony of the two-story building in Vlorë where the Declaration of Independence had just been signed. The establishment of the government was postponed for the fourth session of the Assembly of Vlorë, held on 4 December 1912, until representatives of all regions of Albania arrived to Vlore.[8] Qemali was prime minister of Albania from 1912 to 1914.

In November 1913, Albanian pro-Ottoman forces had offered the Albanian throne to the Ottoman war minister of Albanian origin, Izzet Pasha.[9] The Ottoman Empire sent agents to encourage a revolt, hoping to restore Ottoman suzerainty over Albania.[10] Izzet Pasha sent major Beqir Grebenali, another ethnic Albanian, to be one of his chief representatives in Albania. The Provisional Government of Albania under control of Ismail Qemali captured and executed major Beqir Grebenali. Such provocative and damaging display of independence of Qemali's government angered Great Powers and International Commission of Control forced Qemali to step aside and leave Albania.[11]

During World War I, Ismail Qemali lived in exile in Paris, where, though short of funds, he maintained a wide range of contacts and collaborated with the correspondent of the continental edition of the Daily Mail, Somerville Story, to write his memoirs. His autobiography, published after his death, is the only memoir of a late Ottoman statesman to be written in English and is a unique record of a liberal, multicultural approach to the problems of the dying Empire. In 1918, Ismail Qemali travelled to Italy to promote support for his movement in Albania, but was prevented by the Italian government from leaving Italy and remained as its involuntary guest at a hotel in Perugia, much to his irritation. He died of an apparent heart attack at dinner there one evening. After his death, his body was brought to Vlorë and buried in the local Tekke (Dervish convent) of the Bektashi Order.[12]

Ismail Qemali is depicted on the obverses of the Albanian 200 lekë banknote of 1992–1996,[13] and of the 500 lekë banknote issued since 1996.[14] On 27 June 2012, Albanian President, Bamir Topi decorated Qemali with the Order of the National Flag (Post-mortem).[15]

وزارته

- رئيس الوزراء: إسماعيل كمال

- General Secretary: Qemal Karaosmani

- Deputy Prime Minister: Dom Nikollë Kaçorri

- Minister of Foreign Affairs: Ismail Qemali, then Myfit Libohova

- Minister of Internal Affairs: Myfit Libohova, then Essad Pasha Toptani

- Minister of War: General Mehmet Pashë Dërralla

- Minister of Finance: Abdi Toptani

- Minister of Justice: Dr. Petro Poga

- Minister of Education: Dr. Luigj Gurakuqi

- Minister of Public Services: مدحت فراشيري

- Minister of Agriculture: پندلي تسالى، ثم كمال قرة عثماني

- Minister of Posts and Telegraphs: Lef Nosi

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Giaro, Tomasz (2007). "The Albanian legal and constitutional system between the World Wars". Modernisierung durch Transfer zwischen den Weltkriegen. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Vittorio Klosterman GmbH. p. 185. ISBN 978-3-465-04017-0. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Kondis, Basil (1976). Greece and Albania, 1908-1914. pp. 33-34.

- ^ Pitouli-Kitsou, Hristina (1997). Οι Ελληνοαλβανικές Σχέσεις και το βορειοηπειρωτικό ζήτημα κατά περίοδο 1907- 1914 (Thesis). National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. p. 168. "Ο Ισμαήλ Κεμάλ υπογράμμιζε ότι για να επιβάλει στη σύσκεψη την άποψη του να μην επεκταθεί το κίνημα τους πέραν της Κάτω Αλβανίας, και ταυτόχρονα για να υποδείξει τον τρόπο δράσης που έπρεπε να ακολουθήσουν οι αρχηγοί σε περίπτωση που θα συμμετείχαν σ' αυτό με δική τους πρωτοβουλία και οι Νότιοι Αλβανοί, θα έπρεπε να αποφασίσει η κυβέρνηση την παροχή έκτακτης βοήθειας και να του κοινοποιήσει τις οριστικές αποφάσεις της για την προώθηση του προγράμματος της συνεννόησης, ώστε να ενισχυθεί το κύρος του μεταξύ των συμπατριωτών του. Ειδικότερα δε ο Ισμαήλ Κεμάλ ζητούσε να χρηματοδοτηθεί ο Μουχαρέμ Ρουσήτ, ώστε να μην οργανώσει κίνημα στην περιοχή, όπου κατοικούσαν οι Τσάμηδες, επειδή σ' αυτήν ήταν ο μόνος ικανός για κάτι τέτοιο. Η ελληνική κυβέρνηση, ενήμερη πλέον για την έκταση που είχε πάρει η επαναστατική δράση στο βιλαέτι Ιωαννίνων, πληροφόρησε τον Κεμάλ αρχικά στις 6 Ιουλίου, ότι ήταν διατεθειμένη να βοηθήσει το αλβανικό κίνημα μόνο προς βορράν των Ακροκεραυνίων, και εφόσον οι επαναστάτες θα επι ζητούσαν την εκπλήρωση εθνικών στόχων, εναρμονισμένων με το πρόγραμμα των εθνοτήτων. Την άποψη αυτή φαινόταν να συμμερίζονται μερικοί επαναστάτες αρχηγοί του Κοσσυφοπεδίου. Αντίθετα, προς νότον των Ακροκεραυνίων, η κυβέρνηση δεν θα αναγνώριζε καμιά αλβανική ενέργεια. Απέκρουε γι' αυτόν το λόγο κάθε συνεννόηση του Κεμάλ με τους Τσάμηδες, δεχόταν όμως να συνεργασθεί αυτός, αν χρειαζόταν, με τους επαναστάτες στηνπεριοχή του Αυλώνα."

- ^ Blumi, Isa (2013). Ottoman refugees, 1878-1939: Migration in a post-imperial world. A&C Black. p. 82; p. 195. "As late as 1907 Ismail Qemali advocated the creation of “una liga Greco-Albanese” in an effort to thwart Bulgarian domination in Macedonia. ASAME Serie P Politica 1891–1916, Busta 665, no.365/108, Consul to Foreign Minister, dated Athens, 26 April 1907."

- ^ Blumi, Isa (12 September 2013). Ottoman Refugees, 1878-1939: Migration in a Post-Imperial World. A&C Black. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4725-1538-4.

For example, the Ottoman embassy in Athens reported that Ismail Qemali held negotiations with an organization called Hellenismos, funded by wealthy Tosks and the Greek state. This prominent ex-Ottoman governor apparently was ready to forge a union with the enemy.

- ^ Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening, 1878–1912. Princeton University Press. p. 417. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

The Gerche memorandum, referred to often as "The Red Book" because of the color of its covers

- ^ Treadway, John D (1983), "The Malissori Uprising of 1911", The Falcon and Eagle: Montenegro and Austria-Hungary, 1908–1914, West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, p. 78, ISBN 978-0-911198-65-2, OCLC 9299144, https://books.google.com/books?id=JVJUk2cHkDcC&pg=PA74&dq=%22Malissori+Uprising%22&f=false, retrieved on 10 October 2011

- ^ "Essential Characteristics of the State (1912—1914)", Studia Albanica, 36, Tirana: L'Institut, 2004, p. 18, OCLC 1996482, https://books.google.com/books?ei=vUA0T_OEDMaA4gTRpsypAg&id=B_8VAQAAMAAJ&dq=Shteti+shqiptar+n%C3%AB+vitet+1912-1914&q=representative#search_anchor, "Essential Characteristics of the State (1912—1914) ... The setting up of the government was postponed until the fourth hearing of the Assembly of Vlora, in order to give time to other delegates from all regions of Albania to arrive."

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Albania under prince Wied". Archived from the original on January 25, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

pro-Ottoman forces ...were opposed to the increasing Western influence ...In November 1913, these forces, ..., had offered the vacant Albanian throne to General Izzet Pasha ... War Minister who was of Albanian origin.

- ^ Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9.

... hopes of restoring Ottoman suzerainty over Albania.... sent agents to encourage insurrection

- ^ Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: a modern history. I.B.Tauris. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-86064-541-9.

plot was discovered by Ismail Kemal's agents; one of the Porte's chief representatives, Major Beqir Grebnali... executed

- ^ Müfid Şemsi Paşa: Arnavutluk İttihad ve Terakki, Ahmed Nezih Galitekin, Constantinople, 1995, p. 209.

- ^ Bank of Albania. Currency: Banknotes withdrawn from circulation. – Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ Bank of Albania. Currency: Banknotes in circulation. – Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ http://www.president.al/shqip/info.asp?id=7663

المصادر

- David Barchard, The Man Who Made Albania—Ismail Kemal Bey, Cornucopia Magazine No 34, 2004.

- Ismail Kemal Bey and Sommerville Story, ed. The memoirs of Ismail Kemal Bey. London: Constable and company, 1920. (The Internet Archive, full access)

- Sommerville, A.M. (1927), Twenty years in Paris with a pen, A. Rivers ltd., https://books.google.com/books?id=79akGAAACAAJ

- Xoxi, Koli (1983), Ismail Qemali: jeta dhe vepra, Shtëpia Botuese "8 Nentori", https://books.google.com/books?id=UZ24AAAAIAAJ

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه إعلان الاستقلال |

رأس دولة ألبانيا 1912–1914 |

تبعه William of Wied as a prince |

| سبقه إعلان الاستقلال |

رئيس وزراء ألبانيا 1912–1914 |

تبعه Fejzi Bej Alizoti |

| سبقه إعلان الاستقلال |

وزير الخارجية 1912–1914 |

تبعه |

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).