مملكة لومبارديا-ڤنتيا

مملكة لومبارديا-ڤنتيا | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1815–1866 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| الوضع | Crown land of the الامبراطورية النمساوية | ||||||||||||

| العاصمة | |||||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | اللومباردية، Venetian, Friulian, الإيطالية, والألمانية | ||||||||||||

| الدين | الكنيسة الكاثوليكية | ||||||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية مطلقة | ||||||||||||

| الملك | |||||||||||||

• 1815–1835 | Francis I | ||||||||||||

• 1835–1848 | Ferdinand I | ||||||||||||

• 1848–1866 | Francis Joseph I | ||||||||||||

| نائب الملك | |||||||||||||

• 1815 | Heinrich XV of Reuss-Plauen | ||||||||||||

• 1815–1816 | Heinrich von Bellegarde | ||||||||||||

• 1816–1818 | Anton Victor of Austria | ||||||||||||

• 1818–1848 | Rainer Joseph of Austria | ||||||||||||

• 1848–1857 | Joseph Radetzky von Radetz | ||||||||||||

• 1857–1859 | Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria | ||||||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||||||

| 9 June 1815 | |||||||||||||

| 22 March 1848 | |||||||||||||

• لومبارديا تم التنازل عنها لصالح فرنسا | 10 نوفمبر 1859 | ||||||||||||

| 14 June 1866 | |||||||||||||

| 23 أغسطس 1866 | |||||||||||||

| 12 أكتوبر 1866 | |||||||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||||||

| 1852[2] | 46،782 km2 (18،063 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||||||

• 1852[2] | 4,671,000 | ||||||||||||

| العملة |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| اليوم جزء من | إيطاليا | ||||||||||||

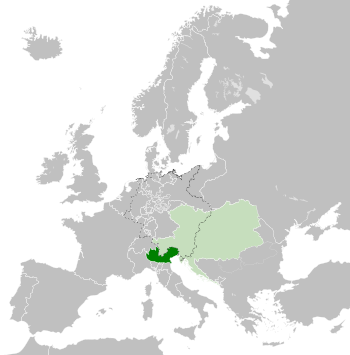

مملكة لومبارديا-ڤنتيا (لاتينية: Regnum Langobardiae et Venetiae)، شاع تسميتها "المملكة اللومباردية-الڤنيتية" (إيطالية: Regno Lombardo-Veneto, ألمانية: Königreich Lombardo-Venetien)، كانت أحد الأراضي (أرض التاج) المكونة للامبراطورية النمساوية من 1815 إلى 1866. وقد أنشئت في 1815 بقرار من مجلس ڤيينا اعترافاً بحقوق بيت هابسبورگ-لورين النمساوي لـدوقية ميلانو السابقة وجمهورية البندقية السابقة بعد مملكة إيطاليا الناپليونية، المعلَنة في 1805، قد انهارت.[3]

اختفت المملكة من الوجود خلال الخمسين عاماً التالية—منطقة لومبارديا أُعطِيت لفرنسا في 1859 بعد حرب الاستقلال الإيطالية الثانية، والتي تنازلت عنها على الفور لـمملكة سردينيا. وأخيراً، تم حل لومبارديا-ڤنتيا في 1866 حين تم ضم ما تبقى من أراضيها إلى مملكة إيطاليا المعلَنة مؤخراً.

التاريخ

الإنشاء

في معاهدة پاريس in 1814, the Austrians had confirmed their claims to the territories of the former Lombard دوقية ميلانو, which had been ruled by the ملكية هابسبورگ منذ 1714 and together with the adjacent دوقية مانتوا by the الفرع النمساوي the dynasty from 1708 to 1796, and of the former جمهورية البندقية، which had been under Austrian rule intermittently upon the 1797 معاهدة كامپو فورميو.

The Congress of Vienna combined these lands into a single kingdom, ruled in personal union by the Habsburg Emperor of Austria; as distinct of the neighbouring Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena and Reggio as well as the Duchy of Parma, which remained independent entities under Habsburg rule. The Austrian emperor was represented day-to-day by viceroys appointed by the Imperial Court in Vienna and resident in Milan and Venice.[2][4][5][6]

سنوات المملكة

The Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia was first ruled by Emperor Francis I from 1815 until his death in 1835. His son Ferdinand I ruled from 1835 to 1848. In Milan on 6 September 1838, he became the last king to be crowned with the Iron Crown of Lombardy. The crown was subsequently brought to Vienna after the loss of Lombardy in 1859 but was restored to Italy after the loss of Venetia in 1866.

Though the local administration was Italian in language and staff, the Austrian authorities had to cope with the Italian unification (Risorgimento) movement. After a popular revolution on 22 March 1848, known as the "Five Days of Milan", the Austrians fled from Milan, which became the capital city of a Governo Provvisorio della Lombardia (Lombardy Provisional Government). The next day, Venice also rose against the Austrian rule, forming the Governo Provvisorio di Venezia (Venice Provisional Government). The Austrian forces under Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky, after defeating the Sardinian troops at the Battle of Custoza (24–25 July 1848), entered Milan (6 August) and Venice (24 August 1849), and once again restored Austrian rule.

Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria ruled over the Kingdom for the rest of its existence. The office of Viceroy was abolished and replaced by a Governor-General. The office was initially assumed by Field Marshal Radetzky - upon his retirement in 1857, it passed it to Franz Joseph's younger brother Maximilian (who later became Emperor of Mexico), who served as Governor-General in Milan from 1857 to 1859.

Political map of the Italian peninsula in the year 1843

نهاية المملكة

After the Second Italian War of Independence and the defeat in the Battle of Solferino in 1859, Austria by the Treaty of Zurich had to cede Lombardy up to the Mincio River, except for the fortresses of Mantua and Peschiera, to the French Emperor Napoleon III, who immediately passed it to the Kingdom of Sardinia and the embryonic Italian state. Maximilian retired to Miramare Castle near Trieste, while the capital was relocated to Venice. However, remaining Venetia and Mantua likewise fell to the Kingdom of Italy in the aftermath of the Third Italian War of Independence, by the 1866 Peace of Prague.[7] The territory of Venetia and Mantua was formally transferred from Austria to France, and then handed over to Italy on 19 October 1866, for diplomatic reasons; a plebiscite marked the Italian annexation on 21–22 October 1866.[8]

الإدارة

Administratively the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia comprised two independent governments (Gubernien) in its two parts, which officially were declared separate crown lands in 1851. Each part was further subdivided in several provinces, roughly corresponding with the départements of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy.

Lombardy included the provinces of Milan, Como, Bergamo, Brescia, Pavia, Cremona, Mantua, Lodi-Crema, and Sondrio. Venetia included the provinces of Venice, Verona, Padua, Vicenza, Treviso, Rovigo, Belluno, and Udine.[7]

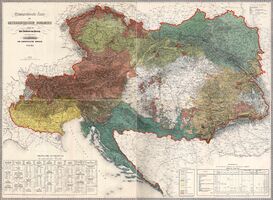

According to the Ethnographic map of Karl von Czoernig-Czernhausen, issued by the Imperial and Royal Administration of Statistics in 1855, the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia then had a population of 5,024,117 people, consisting of the following ethnic groups: 4,625,746 Italians; 351,805 Friulians; 12,084 Germans (Cimbrians in Venetia); 26,676 Slovenians; and 7,806 Jews.

For the first time since 1428, Lombardy reappeared as an entity, the first time in history that term "Lombardy" was officially used to call specifically that entity and not for the whole of Northern Italy.

The administration used Italian as its language in its internal and external communications and documents, and the language's dominant position in politics, finance or jurisdiction was not questioned by the Austrian officials. The Italian-language Gazzetta di Milano was the official newspaper of the kingdom. Civil servants employed in the administration were predominantly Italian, with only about 10% of them being recruited from other regions of the Austrian Empire. Some bilingual Italian-German-speaking civil servants came from the neighboring County of Tyrol. The German language, however, was the command language of the military, and top police officials were native German-speakers from other parts of the empire.[9] The highest governorships were also reserved for Austrian aristocrats.

Austrian General Karl von Schönhals wrote in his memoirs [10] that the Austrian administration enjoyed the support of the rural population and the middle class educated at the universities of Pavia and Padua, who were able to pursue careers in the administration.

Von Schönhals further noted that the Austrians mistrusted and refused the local aristocrats from high government offices, as they traditionally had rejected university education and had been able to gain leadership positions because of their family background. Consequently, the aristocrats saw themselves deprived of the possibility of establishing themselves in the management of society and supported the wars of independence against the Austrians.

Ethnographic map of the Austrian Empire (1855) by de:Karl von Czoernig-Czernhausen

الملوك

| الملك | العهد | الزيجات الأنجال |

حق الخلافة | نائب الملك | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Francis I (Francesco I) 1768 – 1835 (aged 67) |

|

9 June 1815 – 2 March 1835 |

|

1815 – 1816: Heinrich von Bellegarde | |

| 1816 – 1818: Anton Victor of Austria | |||||

| 1818 – 1848: Rainer Joseph of Austria | |||||

| Ferdinand I (Ferdinando I) 1793 – 1875 (aged 82) |

|

2 March 1835 – 2 December 1848 (Abdicated due to 1848 revolutions) |

Maria Anna of Savoy (m. 1831; w. 1878) Childless |

| |

| Franz Joseph I (Francesco Giuseppe I) 1830 – 1916 (aged 86) |

|

2 December 1848 – 12 October 1866 (Forced to cede Lombardy and Venetia) |

Elisabeth in Bavaria (m. 1854; d. 1898) 4 children (3 survived to adulthood) |

|

1848 – 1857: Joseph Radetzky |

| 1857 – 1859: Maximilian of Austria | |||||

| 1859: Ferenc Gyulay | |||||

حكام لومبارديا

- Heinrich Johann Bellegarde 1814–1816

- Franz Josef Graf Saurau 1816–1818

- Giulio Strassoldo di Sotto 1818–1830

- Franz von Hartig 1830–1840

- Robert von Salm-Reifferscheidt-Raitz 1840–1841

- Johann Baptist Spaur 1841–1848

- Maximilian Karl Lamoral O'Donnell 1848 (acting)

- Felix von Schwarzenberg 1848

- Franz Wimpffen 1848 (acting)

- Alberto Montecuccoli-Laderchi 1848–1849 (acting)

- Karl Borromäus Philipp zu Schwarzenberg 1849–1850 (acting)

- Michele Strassoldo-Grafenberg 1851–1857 (with the title of Lieutenant of Lombardy)

- Friedrich von Burger 1857–1859

حكام ڤنتيا

- Peter Goëss 1815–1819

- Ferdinand Ernst Maria von Bissingen-Nippenburg 1819–1820

- Carlo d'Inzaghi 1820–1826

- Johann Baptist Spaur 1826–1840

- Aloys Pállfy de Erdöd 1840–1848

- Ferdinand Zichy zu Zich von Vasonykeöy 1848 (acting)

- Laval Nugent von Westmeath 1848–1849 (military governor)

- Karl von Gorzowsky 1849

- Stanislaus Anton Puchner 1849–1850

- Georg Otto von Toggenburg-Sargans 1850–1855

- Kajetan von Bissingen-Nippenburg 1855–1860

- Georg Otto von Toggenburg-Sargans 1860–1866 (second time)

المصادر

- ^ Pütz, Wilhelm (1855). Leitfaden bei dem Unterricht in der vergleichenden Erdbeschreibung. Freiburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب ت Fisher, Richard S. (1852). The Book of the World: Volume 2. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rindler Schjerve, Rosita (2003). Diglossia and Power. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Francis Young & W.B.B. Stevens (1864). Garibaldi: His Life and Times. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Pollock, Arthur William Alsager (1854). The United Service magazine: Vol.75. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Förster, Ernst (1866). Handbuch für Reisende in Italien: Vol.1. Munich.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب Rosita Rindler Schjerve (2003). Diglossia and Power: Language Policies and Practice in the 19th Century Habsburg Empire. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 199–200. ISBN 3-11-017653-X. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "21st-22nd October 1866: annexation of Veneto to Italy" (in Italian)

- ^ Boaglio, Gualtiero. 2003. 6. Language and power in an Italian crownland of the Habsburg Empire: The ideological dimension of diglossia in Lombardy

- ^ Erinnerungen eines österreichischen Veteranen aus dem italienischen Kriege der Jahre 1848 und 1849 Autor / Hrsg.: Schönhals, Karl von ; Schönhals, Karl von

وصلات خارجية

Media related to Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia at Wikimedia Commons- Flags of Lombardy–Venetia

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إيطالية-language text

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مملكة لومبارديا-ڤنتيا

- القرن 19 في إيطاليا

- انحلالات 1866 في أوروپا

- Italian unification

- تاريخ لومباريدا

- تاريخ البندقية بعد 1797

- تقسيمات النمسا-المحر

- بيت هابسبورگ-لورين

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1815

- تأسيسات 1815 في أوروپا

- History of Veneto

- بلدان سابقة