الرواق الپولندي

| التطور الإقليمي لألمانيا في القرن العشرين |

|---|

| ||

|---|---|---|

الرواق الپولندي Polish Corridor هو شريط ضيق من الأرض انتُزع من ألمانيا بعد هزيمتها في الحرب العالمية الأولى (1914م ـ 1918م) وأُعطِي لبولندا.

أقيم هذا الممر سنة 1919 بمقتضى معاهدة ڤرساي، التي أنهت الحرب مع ألمانيا لإعطاء بولندا طريقًا مباشرا للوصول إلى بحر البلطيق. وكانت مساحة الممر ذات يوم جزءًا من إقليم بولندي يُسمى پومرانيا. واستولت پروسيا على هذه الأرض في 1772م، وأصبح الإقليم تحت سيطرة ألمانيا عندما أصبحت بروسيا ولاية ألمانية في 1871. ويشمل الإقليم الزراعي الكبير مدن بيد جوزيذ، وجرودزيادز، وتورون وميناء گدينيا البحري. كان الممر يفصل منطقة پروسيا الشرقية، عن بقية الأراضي الألمانية، وكان نصف السكان تقريباً يتكلمون اللغة الألمانية، ثم جاء وقت تنازعت ألمانيا وبولندا حول ملكية الأرض.

30 Aug 1939: German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop tells the #British ambassador that to ensure peace with Poland, Danzig would return to Germany and a plebiscite in the #Polish Corridor would occur but Poles born/settled there since 1919 couldn’t vote. في 1939، استعادت ألمانيا سيطرتها على الممر.

وبعد نهاية الحرب العالمية الثانية، في 1945، أصبح الممر ونصف بروسيا الشرقية جزءًا من بولندا.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Background

History of the area

In the 10th century, Pomerelia was settled by Slavic Pomeranians, ancestors of the Kashubians, who were subdued by Bolesław I of Poland. In the 11th century, they created an independent duchy.[1] In 1116/1121, Pomerania was again conquered by Poland. In 1138, following the death of Duke Bolesław III, Poland was fragmented into several semi-independent principalities. The Samborides, principes in Pomerelia, gradually evolved into independent dukes, who ruled the duchy until 1294. Before Pomerelia regained independence in 1227,[1][2] their dukes were vassals of Poland and Denmark. Since 1308–1309, following succession wars between Poland and Brandenburg, Pomerelia was subjugated by the Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia. In 1466, with the second Peace of Thorn, Pomerelia became part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as a part of autonomous Royal Prussia. After the First Partition of Poland in 1772 it was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia and named West Prussia, and became a constituent part of the new German Empire in 1871. Thus the Polish Corridor was not an entirely new creation: the territory assigned to Poland had been an integral part of Poland prior to 1772, but with a large degree of autonomy.[3][4][5][6]

التعداد التاريخي

Perhaps the earliest census data on ethnic or national structure of West Prussia (including areas which later became the Polish Corridor) is from 1819.[7]

| Ethnic or national group | Population (number) | Population (percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Poles (Polen) | 327,300 | 52% |

| Germans (Deutsche) | 290,000 | 46% |

| Jews (Juden) | 12,700 | 2% |

| Total | 630,077 | 100% |

Karl Andree, "Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht" (Leipzig 1831), gives the total population of West Prussia as 700,000 inhabitants - including 50% Poles (350,000), 47% Germans (330,000) and 3% Jews (20,000).[8]

Data from the 19th century and early 20th century show the following ethnic changes in four "core" counties of the Corridor (Puck, Wejherowo - directly at the Baltic Sea coast - and Kartuzy, Kościerzyna - between Provinz Pommern and Free City Danzig):

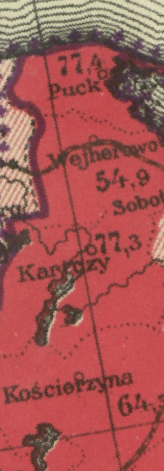

خريطة پوك (77.4%), Wejherowo (54.9%), Kartuzy (77.3%) and Kościerzyna (64.5%) counties, showing percentages of ethnic Poles (including Kashubians) by the end of World War I, according to the Map of Polish population published in 1919 in Warsaw.[9]

| المقاطعة | Puck (Putzig) | Wejherowo (Neustadt) | Kartuzy (Karthaus) | Kościerzyna (Berent) | Source: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||||

| 1831 | 82%

|

85%

|

72%

|

J. Mordawski's estimate[10] | |

| 1831 | 78%

|

84%

|

71%

|

Leszek Belzyt's estimate[11] | |

| 1837 | 77%

|

84%

|

71%

|

Volkszählung pop. census[12] | |

| 1852 | 80%

|

77%

|

64%

|

Volkszählung[12] | |

| 1855 | 80%

|

76%

|

64%

|

Volkszählung[12] | |

| 1858 | 79%

|

76%

|

63%

|

Volkszählung[12] | |

| 1861 | 80%

|

77%

|

64%

|

Leszek Belzyt's estimate[11] | |

| 1886 | 75%

|

64%

|

66%

|

57%

|

Schulzählung school census[12] |

| 1890 | 69%

|

56%

|

67%

|

54%

|

Volkszählung[12] |

| 1890 | 73%

|

61%

|

68%

|

57%

|

Leszek Belzyt's estimate[11] |

| 1891 | 74%

|

62%

|

66%

|

56%

|

Schulzählung[12] |

| 1892 | 77%

|

67%

|

76%

|

59%

|

Stefan Ramułt's estimate[13][14] |

| 1896 | 72%

|

61%

|

70%

|

58%

|

Schulzählung[12] |

| 1900 | 69%

|

54%

|

69%

|

55%

|

Volkszählung[12] |

| 1901 | 76%

|

60%

|

71%

|

59%

|

Schulzählung[12] |

| 1905 | 70%

|

51%

|

70%

|

56%

|

Volkszählung[12] |

| 1906 | 73%

|

62%

|

72%

|

60%

|

Schulzählung[12] |

| 1910 | 70%

|

50%

|

72%

|

58%

|

Volkszählung[12] |

| 1910 | 74%

|

62%

|

74%

|

62%

|

Leszek Belzyt's estimate[11] |

| 1911 | 74%

|

63%

|

74%

|

63%

|

Schulzählung[12] |

| 1918 | 77%

|

55%

|

77%

|

65%

|

Map of Polish population[9][15] |

| 1921 | 89%

|

92%

|

81%

|

Polish General Census[16][17] | |

| 1931 | 95%

|

93%

|

88%

|

Polish General Census | |

Allied plans for a corridor after World War I

During the First World War, both sides made bids for Polish support, and in turn Polish leaders were active in soliciting support from both sides. Roman Dmowski, a former deputy in the Russian State Duma and the leader of the Endecja movement was especially active in seeking support from the Allies. Dmowski argued that an independent Poland needed access to the sea on demographic, historical and economic grounds as he maintained that a Poland without access to the sea could never be truly independent. After the war Poland was to be re-established as an independent state. Since a Polish state had not existed since the Congress of Vienna, the future republic's territory had to be defined.

Giving Poland access to the sea was one of the guarantees proposed by United States President Woodrow Wilson in his Fourteen Points of January 1918. The thirteenth of Wilson's points was:

- "An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant."[18]

The following arguments were behind the creation of the corridor:

Ethnographic reasons

The ethnic situation was one of the reasons for returning the area to the restored Poland.[19] The majority of the population in the area was Polish.[20] As the Polish commission report to the Allied Supreme Council noted on 12 March 1919: "Finally the fact must be recognised that 600,000 Poles in West Prussia would under any alternative plan remain under German rule".[21] Also, as David Hunter Miller from president Woodrow Wilson's group of experts and academics (known as The Inquiry) noted in his diary from the Paris Peace Conference: "If Poland does not thus secure access to the sea, 600,000 Poles in West Prussia will remain under German rule and 20,000,000 Poles in Poland proper will probably have but a hampered and precarious commercial outlet".[22] The Prussian census of 1910 showed that there were 528,000 Poles (including West Slavic Kashubians, who had supported the Polish national lists in German elections[23][24][25][26]) in the region, compared with 385,000 Germans (including troops and officials stationed in the area).[27][28] The province of West Prussia as a whole had between 36% and 43% ethnic Poles in 1910, depending on the source (the lower number is based directly on German 1910 census figures, while the higher number is based on calculations according to which a large part of those people counted as Catholic Germans in the official census in fact identified as Poles).[29] The Poles did not want the Polish population to remain under the control of the German state,[30] which had in the past treated the Polish population and other minorities as second-class citizens[31] and had pursued Germanization. As Professor Lewis Bernstein Namier (1888–1960) -- born to Jewish parents in Lublin Governorate (Russian Empire, former Congress Poland) and later a British citizen,[32] a former member of the British Intelligence Bureau throughout World War I[33] and the British delegation at the Versailles conference,[34] known for his anti-Polish[35] and anti-German[36][37] attitude—wrote in the Manchester Guardian on November 7, 1933: "The Poles are the Nation of the Vistula, and their settlements extend from the sources of the river to its estuary. … It is only fair that the claim of the river-basin should prevail against that of the seaboard."[38]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Economic reasons

The Poles held the view that without direct access to the Baltic Sea, Poland's economic independence would be illusory.[39] Around 60.5% of Polish import trade and 55.1% of exports went through the area.[40] The report of the Polish Commission presented to the Allied Supreme Council said:

- "1,600,000 Germans in East Prussia can be adequately protected by securing for them freedom of trade across the corridor, whereas it would be impossible to give an adequate outlet to the inhabitants of the new Polish state (numbering 25,000,000) if this outlet had to be guaranteed across the territory of an alien and probably hostile Power."[41]

The United Kingdom eventually accepted this argument.[39] The suppression of the Polish Corridor would have abolished the economic ability of Poland to resist dependence on Germany.[42] As Lewis Bernstein Namier, Professor of Modern History at the University of Manchester and known for both his "legendary hatred of Germany"[36] and Germanophobia[37] as well as his anti-Polish attitude[35] directed against what he defined as the "aggressive, antisemitic and warmongerily imperialist" part of Poland,[43] wrote in a newspaper article in 1933:

- "The whole of Poland's transport system ran towards the mouth of the Vistula....

- "90% of Polish exports came from her western provinces.[44]

- "Cutting through of the Corridor has meant a minor amputation for Germany; its closing up would mean strangulation for Poland.".[45]

By 1938, 77.7% of Polish exports left either through Gdańsk (31.6%) or the newly built port of Gdynia (46.1%)[46]

The Inquiry's opinion

David Hunter Miller in his diary from the Paris Peace Conference noted, that the problem of Polish access to the sea was very difficult because leaving entire Pomerelia under German control meant cutting off millions of Poles from their commercial outlet and leaving several hundred thousand Poles under German rule, while granting such access meant cutting off East Prussia from the rest of Germany. The Inquiry recommended, that both the Corridor and Danzig should have been ceded directly to Poland.

Quote: "It is believed that the lesser of these evils is preferable, and that the Corridor and Danzig should [both] be ceded to Poland, as shown on map 6. East Prussia, though territorially cut off from the rest of Germany, could easily be assured railroad transit across the Polish corridor (a simple matter as compared with assuring port facilities to Poland), and has, in addition, excellent communication via Königsberg and the Baltic Sea. In either case a people is asked to entrust large interests to the League of Nations. In the case of Poland they are vital interests; in the case of Germany, aside from Prussian sentiment, they are quite secondary".[22]

In the end, The Inquiry's recommendations were implemented only partially: most of West Prussia was given to Poland, but Danzig became a Free City.

Incorporation into the Second Polish Republic

During World War I, the Central Powers had forced the Imperial Russian troops out of Congress Poland and Galicia, as manifested in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918. Following the military defeat of Austria-Hungary, an independent Polish republic was declared in Western Galicia on 3 November 1918, the same day Austria signed the armistice. The collapse of Imperial Germany's Western Front, and the subsequent withdrawal of her remaining occupation forces after the Armistice of Compiègne on 11 November allowed the republic led by Roman Dmowski and Józef Piłsudski to seize control over the former Congress Polish areas. Also in November, the revolution in Germany forced the Kaiser's abdication and gave way to the establishment of the Weimar Republic. Starting in December, the Polish-Ukrainian War expanded the Polish republic's territory to include Volhynia and parts of Eastern Galicia, while at the same time the German Province of Posen (where even according to the German made 1910 census 61,5% of the population was Polish) was severed by the Greater Poland uprising, which succeeded in attaching most of the province's territory to Poland by January 1919. This led Weimar's Otto Landsberg and Rudolf Breitscheid to call for an armed force to secure Germany's remaining eastern territories (some of which contained significant Polish minorities, primarily on the former Prussian partition territories). The call was answered by the minister of defense Gustav Noske, who decreed support for raising and deploying volunteer de (Grenzschutz) forces to secure East Prussia, Silesia and the Netze District.[47]

On 18 January, the Paris peace conference opened,[48] resulting in the draft of the Treaty of Versailles 28 June 1919. Articles 27 and 28 of the treaty[49] ruled on the territorial shape of the corridor, while articles 89 to 93 ruled on transit, citizenship and property issues.[50] Per the terms of the Versailles treaty, which was put into effect on 20 January 1920, the corridor was established as Poland's access to the Baltic Sea from 70% of the dissolved province of West Prussia,[51] consisting of a small part of Pomerania with around 140 km of coastline including the Hel Peninsula, and 69 km without it.[52]

The primarily German-speaking seaport of Danzig (Gdańsk), controlling the estuary of the main Polish waterway, the Vistula river, became the Free City of Danzig and was placed under the protection of the League of Nations without a plebiscite.[53] After the dock workers of Danzig harbour went on strike during the Polish–Soviet War, refusing to unload ammunition,[54] the Polish Government decided to build an ammunition depot at Westerplatte, and a seaport at Gdynia in the territory of the Corridor, connected to the Upper Silesian industrial centers by the newly constructed Polish Coal Trunk Line railways.

نزوح الأقلية الألمانية

| المقاطعة | التعداد الكلي | الألمان فيهم | النسبة |

|---|---|---|---|

| Działdowo (Soldau) | 23,290 | 8,187 | 34.5 % (35.2%) |

| Lubawa (Löbau) | 59,765 | 4,478 | 7.6 % |

| Brodnica (Strasburg) | 61,180 | 9,599 | 15.7% |

| Wąbrzeźno (Briesen) | 47,100 | 14,678 | 31.1% |

| Toruń (Thorn) | 79,247 | 16,175 | 20.4% |

| Chełmno (Kulm) | 46,823 | 12,872 | 27.5% |

| Świecie (Schwetz) | 83,138 | 20,178 | 24.3% |

| Grudziądz (Graudenz) | 77,031 | 21,401 | 27.8% |

| Tczew (Dirschau) | 62,905 | 7,854 | 12.5% |

| Wejherowo (Neustadt) | 71,692 | 7,857 | 11.0% |

| Kartuzy (Karthaus) | 64,631 | 5,037 | 7.8% |

| Kościerzyna (Berent) | 49,935 | 9,290 | 18.6% |

| Starogard Gdański (Preußisch Stargard) | 62,400 | 5,946 | 9.5% |

| Chojnice (Konitz) | 71,018 | 13,129 | 18.5% |

| Tuchola (Tuchel) | 34,445 | 5,660 | 16.4% |

| Sępólno Krajeńskie (Zempelburg) | 27,876 | 13,430 | 48.2% |

| الإجمالي | 935,643 (922,476 when added) |

175,771 |

18.8% (19.1% with 922,476) |

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية

At the 1945 Potsdam Conference following the German defeat in World War II, Poland's borders were reorganized at the insistence of the Soviet Union, which occupied the entire area. Territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, including Danzig, were put under Polish administration. The Potsdam Conference did not debate about the future of the territories that were part of western Poland before the war, including the corridor. It automatically became part of the reborn state in 1945.

Many German residents were executed,[بحاجة لمصدر] others were expelled to the منطقة الاحتلال السوڤيتي، التي أصبحت لاحقاً ألمانيا الشرقية.

الرواق في الأدب

In The Shape of Things to Come, published in 1933, H. G. Wells correctly predicted that the corridor would be the starting point of a future Second World War. He depicted the war as beginning in January 1940 and would involve heavy aerial bombing of civilians, but that it would result in a 10-year trench warfare-esque stalemate between Poland and Germany eventually leading to a worldwide societal collapse in the 1950's.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

ممرات مماثلة

التالون هم ممرات أرضية أخرى لتربط بلد ما إما بالبحر أو بجزء قاص من هذا البلد:

- الممر التشيكي (مفهوم)

- ممر إيلات[56] (إسرائيل)

- ممر القدس (إسرائيل)

- أنتوفاگاستا[56] أو ممر أتاكاما (بوليڤيا)

- ممر لاچين (أرمينيا/أذربيجان)

- ممر سيليگوري (الهند)

- ممر تين بيغا (بنگلادش)

- ممر وخان (أفغانستان، هذا الممر لم يخلق ليربط مناطق، بل ليفصل مناطق)

- رواق برتشكو (جمهورية صرب البوسنة، البوسنة والهرسك)

- كاليننگراد هو طريق وسكة حديد بعد انهيار الاتحاد السوڤيتي، يربطا عبر لتوانيا وبلاروس إلى روسيا نفسها من الجيب الخارجي الروسي كاليننگراد الذي أصبح مفصولاً.

الهامش

- ^ أ ب James Minahan, One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, p.375, ISBN 0-313-30984-1

- ^ W.D. Halsey, L. Shores, Bernard Johnston, Emanuel Friedman, Merit Students Encyclopedia, Macmillan Educational Corporation, 1979, p.195: Pomerelia, independent in 1227 and thereafter

- ^ A Lasting Peace page 127, James Clerk Maxwell Garnett, Heinrich F. Koeppler – 1940

- ^ Arms and Policy, 1939–1944 page 40, Hoffman Nickerson – 1945

- ^ The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity, 1812–1822 page 279, Harold Nicolson. Grove Pres 2000

- ^ Urban Societies in East-Central Europe, page 190,191, Jaroslav Miller 2008

- ^ أ ب Hassel, Georg (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt. Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. p. 42.

- ^ Andree, Karl (1831). Polen: in geographischer, geschichtlicher und culturhistorischer Hinsicht. Verlag von Ludwig Schumann. p. 212.

- ^ أ ب Dura, Lucjusz (1919). "Mapa rozsiedlenia ludności polskiej: z uwzględnieniem spisów władz okupacyjnych w 1916 r. [Map of the distribution of Polish population: taking into account the censuses of 1916]". polona.pl/. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Mordawski, Jan (2017). Atlas dziejów Pomorza i jego mieszkańców - Kaszubów (PDF) (in البولندية). Gdańsk: Zrzeszenie Kaszubsko-Pomorskie. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-83-62137-38-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Belzyt, Leszek (2017). "Kaszubi w świetle pruskich danych spisowych w latach 1827-1911. Tabela 24. Procentowy udział Kaszubów w poszczególnych powiatach według korekty" (PDF). Acta Cassubiana. 19: 233. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-03. Retrieved 2019-10-31 – via BazHum MuzHP.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص Belzyt, Leszek (2017). "Kaszubi w świetle pruskich danych spisowych w latach 1827-1911 [Kashubians in the light of Prussian census data in years 1827-1911]" (PDF). Acta Cassubiana. 19: 194–235. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-07-03. Retrieved 2019-10-31 – via BazHum MuzHP.

- ^ "Temat 19: Kaszubi w statystyce (cz. I)" (PDF). kaszebsko.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Ramułt, Stefan (1899). Statystyka ludności kaszubskiej (in البولندية). Cracow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Andrzejewski, Czesław (1919). Żywioł niemiecki w zachodniej Polsce. Poznań.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Szczurek, Wiesław (2002). "Liczba i rozmieszczenie ludności niemieckiej na Pomorzu w okresie II Rzeczypospolitej". Państwo i społeczeństwo. 2 (II): 163–175. ISSN 1643-8299 – via Repozytorium eRIKA.

- ^ Blanke, Richard (1993). Orphans of Versailles. The Germans in Western Poland 1918-1939. Lexington, KY.: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 244–245. ISBN 978-0813156330.

- ^ The text of Woodrow's Fourteen Points Speech Archived 2005-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Danzig Dilemma; a Study in Peacemaking by Compromise: A Study in Peacemaking by Compromise-"This report was origin of the famous Polish corridor to the Baltic which the Commission proposed on ethnographic grounds as well as to give Poland her promised free and secure access to the sea", John Brown Mason, page 50

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala, Natalia Sergeevna Lebedeva, Wojciech Materski, Maia A. Kipp, Katyn: A Crime without Punishment, Yale University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-300-10851-6, Google Print, p.15

- ^ The Danzig Dilemma; a Study in Peacemaking by Compromise: A Study in Peacemaking by Compromise John Brown Mason page 49

- ^ أ ب Hunter Miller, David (1924). My Diary at Conference of Paris. Vol. IV. New York: Appeal Printing Company. pp. 224–227.

- ^ Gdańskie Zeszyty Humanistyczne: Seria pomorzoznawcza Page 17, Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna (Gdańsk). Wydział Humanistyczny, Instytut Bałtycki, Instytut Bałtycki (Poland) – 1967

- ^ Położenie mniejszości niemieckiej w Polsce 1918–1938 Page 183, Stanisław Potocki – 1969

- ^ Rocznik gdański organ Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauki i Sztuki w Gdańsku – page 100, 1983

- ^ Do niepodległości 1918, 1944/45, 1989: wizje, drogi, spełnienie page 43, Wojciech Wrzesiński – 1998

- ^ "Principles and Problems of International Relations" page 608 H. Arthur Steiner – 1940

- ^ Blanke, Richard. (Appendix B. German Population of Western Poland by Province and Country). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813130417.

- ^ Kozicki, Stanislas (1918). The Poles under Prussian rule. London: Polish Press Bur. p. 5.

- ^ The Danzig Dilemma a Study in Peacemaking by Compromise by John Brown Mason Stanford University Press 1946, page 49

- ^ A History of Modern Germany, 1800–2000 page 130, Martin Kitchen Blackwell Publishing 2006

- ^ Albert S. Lindemann (2000). Anti-Semitism before the Holocaust. Pearson. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-582-36964-1. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

Kelly Boyd (1999). Encyclopedia of historians and historical writing. Fitzroy Dearborn. ISBN 978-1-884964-33-6. Retrieved 2009-07-06. - ^ Gary S. Messinger (1992). British Propaganda and the State in the First World War. Manchester University Press ND. ISBN 978-0-7190-3014-7. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ Christopher Hill, Pamela Beshoff (1994). Two Worlds of International Relations. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06970-0. Retrieved 2009-07-06.

- ^ أ ب Niepodległość, Tom 21 Pilsudski Institute of America Instytut Józefa Piłsudskiego Poświecony Badaniu Najnowszej Historii Polski., 1988 page 58

- ^ أ ب Wrigley, Chris (2006). A.J.P. Taylor, Radical Historian of Europe. I.B. Tauris. p. 70. ISBN 1-86064-286-1.

Namier.

- ^ أ ب Crozier, Andrew J. (1997). The causes of the Second World War. Wiley. ISBN 9780631186014.

- ^ In the Margin of History, p 44 by Lewis Bernstein Namier

- ^ أ ب Out of the Ashes James Thorburn Muirhead 1941, page 54

- ^ The Crises of France's East Central European Diplomacy, 1933-1938 - page 40 Anthony Tihamer Komjathy - 1976

- ^ The Danzig dilemma: a study in peacemaking by compromise by John Brown Mason Stanford university press 1946, page 49

- ^ Review of Reviews page 67 author Albert Shaw 1931

- ^ Chasin, Stephanie (2008). Citizens of Empire: Jews in the Service of the British Empire (1906-1949). University of California. p. 206. ISBN 9781109022278.[dead link]

- ^ The New Europe, page 91 - by Bernard Newman, 1942

- ^ In the Margin of History - page 44Lewis Bernstein Namier - (pub. 1969)

- ^ Przegląd zachodni: Volume 60, Issues 3-4Instytut Zachodni - 2004, page 42 view

- ^ T. Hunt Tooley, National identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the eastern border, 1918-1922, University of Nebraska Press, 1997, pp.36-37, ISBN 0-8032-4429-0

- ^ T. Hunt Tooley, National identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the eastern border, 1918-1922, University of Nebraska Press, 1997, p.38, ISBN 0-8032-4429-0

- ^ Treaty of Versailles, §§1-30 [1]

- ^ Treaty of Versailles, §§31-117 [2]

- ^ "BPB on Poland".

- ^ Leśniewski, Andrzej; et al. (1959). Sobański, Wacław (ed.). Western and Northern territories of Poland : Facts and problems. Studies and monographs. Poznań – Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Zachodnie (Publishing House of the Zachodnia Agencja Prasowa). p. 7.

- ^ Eberhard Kolb, The Weimar Republic, 2nd edition, Routledge, 2004, p.27, ISBN 0-415-34442-5 [3]

- ^ The Danzig dilemma a study in peacemaking by compromise by John Brown Mason Stanford university press 1946, page 116

- ^ Richard Blanke, Orphans of Versailles: The Germans in Western Poland 1918-1939, University of Kentucky Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8131-1803-4 [4]

- ^ أ ب Peter Haggett, Geography: A Global Synthesis, Pearson Education, 2001, p.524, ISBN 0582320305

- CS1 البولندية-language sources (pl)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Articles with dead external links from February 2023

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2020

- ما بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى في ألمانيا

- تاريخ پومرانيا

- الجمهورية الپولندية الثانية

- معاهدة ڤرساي

- العلاقات الألمانية الپولندية

- ما بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى في پولندا

- أروقة جيوسياسية

- تأسيسات 1920 في پولندا