خط كرزون

| Historical demarcation line of World War II | |

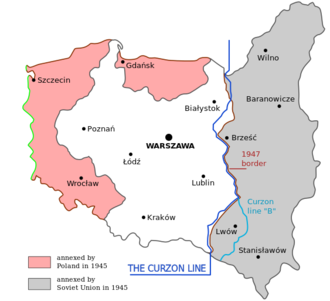

Lighter blue line: Curzon Line "B" as proposed in 1919. Darker blue line: "Curzon" Line "A" as drawn by Lewis Namier in 1919. Pink areas: Pre–World War II provinces of Germany transferred to Poland after the war. Grey area: Pre–World War II Polish territory east of the Curzon Line annexed by the Soviet Union after the war. |

خط كرزون Curzon Line كان خط ترسيم حدود مقترح بين الجمهورية البولندية الثانية و Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to the Supreme War Council in 1919 (based on a suggestion by Herbert James Paton) as a diplomatic basis for a future border agreement.[1][2][3]

The line became a major geopolitical factor during World War II, when the USSR invaded eastern Poland, resulting in the split of Poland's territory between the USSR and Nazi Germany along the Curzon Line. After the German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941, Operation Barbarossa, the Allies did not agree that Poland's future eastern border should be kept as drawn in 1939 until the Tehran Conference. Churchill's position changed after the Soviet victory at the Battle of Kursk.[4]

Following a private agreement at the Tehran Conference, confirmed at the 1945 Yalta Conference, the Allied leaders Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Stalin issued a statement affirming the use of the Curzon Line, with some five-to-eight-kilometre variations, as the eastern border between Poland and the Soviet Union.[5] When Churchill proposed to annex parts of Eastern Galicia, including the city of Lviv, to Poland's territory (following Line B), Stalin argued that the Soviet Union could not demand less territory for itself than the British Government had reconfirmed previously several times. The Allied arrangement involved compensation for this loss via the incorporation of formerly German areas (the so-called Recovered Territories) into Poland. As a result, the current border between Poland and the countries of Belarus and Ukraine is an approximation of the Curzon Line.

| ||

|---|---|---|

التاريخ المبكر

At the end of World War I, the Second Polish Republic reclaimed its sovereignty following the disintegration of the occupying forces of three neighbouring empires. Imperial Russia was amid the Russian Civil War after the October Revolution, Austria-Hungary split and went into decline, and the German Reich bowed to pressure from the victorious forces of the Allies of World War I known as the Entente Powers. The Allied victors agreed that an independent Polish state should be recreated from territories previously part of the Russian, the Austro-Hungarian and the German empires, after 123 years of upheavals and military partitions by them.[6]

The Supreme War Council tasked the Commission on Polish Affairs with recommending Poland's eastern border, based on spoken language majority, which became later known as the Curzon Line.[7] Their result was created Dec 8th 1919. The Allies forwarded it as an armistice line several times during the subsequent Polish-Soviet Wars,[7] most notably in a note from the British government to the Soviets signed by Lord Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary. Both parties disregarded the line when the military situation lay in their favour, and it did not play a role in establishing the Polish–Soviet border in 1921. Instead, the final Peace of Riga (or Treaty of Riga) provided Poland with almost 135،000 متر كيلومربع (52،000 sq mi) of land that was, on average, about 250 كيلومتر (160 mi) east of the Curzon Line.

السمات

The northern half of the Curzon Line lay approximately along the border which was established between the Prussian Kingdom and the Russian Empire in 1797, after the Third Partition of Poland, which was the last border recognised by the United Kingdom. Along most of its length, the line followed an ethnic boundary - areas west of the line contained an overall Polish majority while areas to its east were inhabited by Ukrainians, Belorussians, Poles, Jews, and Lithuanians.[8][9][10][11][12] Its 1920 northern extension into Lithuania divided the area disputed between Poland and Lithuania. There were two versions of the southern portion of the line: "A" and "B". Version "B" allocated Lwów (Lviv) to Poland.

نهاية الحرب العالمية الأولى

The US President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points included the statement "An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea..." Article 87 of the Versailles Treaty stipulated that "The boundaries of Poland not laid down in the present Treaty will be subsequently determined by the Principal Allied and Associated Powers." In accordance with these declarations, the Supreme War Council tasked the Commission on Polish Affairs with proposing Poland's eastern boundaries in lands that were inhabited by a mixed population of Poles, Lithuanians, Ukrainians and Belorussians.[13][14] The Commission issued its recommendation on 22 April; its proposed Russo-Polish borders were close to those of the 19th-century Congress Poland.[14]

The Supreme Council continued to debate the issue for several months. On 8 December, the Council published a map and description of the line along with an announcement that it recognized "Poland's right to organize a regular administration of the territories of the former Russian Empire situated to the West of the line described below."[14] At the same time, the announcement stated the Council was not "...prejudging the provisions which must in the future define the eastern frontiers of Poland" and that "the rights that Poland may be able to establish over the territories situated to the East of the said line are expressly reserved."[14] The announcement had no immediate impact, although the Allies recommended its consideration in an August 1919 proposal to Poland, which was ignored.[14][15]

الحرب البولندية السوفيتية 1919-1921

Polish forces pushed eastward, taking Kiev in May 1920. Following a strong Soviet counteroffensive, Prime Minister Władysław Grabski sought Allied assistance in July. Under pressure, he agreed to a Polish withdrawal to the 1919 version of the line and, in Galicia, an armistice near the current line of battle.[16] On 11 July 1920, Lord Curzon of Kedleston signed a telegram sent to the Bolshevik government proposing that a ceasefire be established along the line, and his name was subsequently associated with it.[14]

Curzon's July 1920 proposal differed from the 19 December announcement in two significant ways.[17] The December note did not address the issue of Galicia, since it had been a part of the Austrian Empire rather than the Russian, nor did it address the Polish-Lithuanian dispute over the Vilnius Region, since those borders were demarcated at the time by the Foch Line.[17] The July 1920 note specifically addressed the Polish-Lithuanian dispute by mentioning a line running from Grodno to Vilnius (Wilno) and thence north to Daugavpils, Latvia (Dynaburg).[17] It also mentioned Galicia, where earlier discussions had resulted in the alternatives of Line A and Line B.[17] The note endorsed Line A, which included Lwów and its nearby oil fields within Russia.[18] This portion of the line did not correspond to the current line of battle in Galicia, as per Grabski's agreement, and its inclusion in the July note has lent itself to disputation.[16]

On 17 July, the Soviets responded to the note with a refusal. Georgy Chicherin, representing the Soviets, commented on the delayed interest of the British for a peace treaty between Russia and Poland. He agreed to start negotiations as long as the Polish side asked for it. The Soviet side at that time offered more favourable border solutions to Poland than the ones offered by the Curzon Line.[19] In August the Soviets were defeated by the Poles just outside Warsaw and forced to retreat. During the ensuing Polish offensive, the Polish government repudiated Grabski's agreement with regard to the line on the grounds that the Allies had not delivered support or protection.[20]

سلام ريگا

At the March 1921 Treaty of Riga the Soviets conceded[21] a frontier well to the east of the Curzon Line, where Poland had conquered a great part of the Vilna Governorate (1920/1922), including the town of Wilno (Vilnius), and East Galicia (1919), including the city of Lwów, as well as most of the region of Volhynia (1921). The treaty provided Poland with almost 135،000 متر كيلومربع (52،000 sq mi) of land that was, on average, about 250 كيلومتر (160 mi) east of the Curzon Line.[22][23] The Polish-Soviet border was recognised by the League of Nations in 1923[بحاجة لمصدر] and confirmed by various Polish-Soviet agreements.[بحاجة لمصدر] Within the annexed regions, Poland founded several administrative districts, such as the Volhynian Voivodeship, the Polesie Voivodeship, and the Wilno Voivodeship.

As a concern of possible expansion of Polish territory, Polish politicians traditionally could be subdivided into two opposite groups advocating contrary approaches: restoration of Poland based on its former western territories one side and, alternatively, restoration of Poland based on its previous holdings in the east on the other. During the first quarter of the 20th century, a representative of the first political group was Roman Dmowski, an adherent of the pan-slavistic movement and author of several political books and publications[24] of some importance, who suggested to define Poland's eastern border in accordance with the ethnographic principle and to concentrate on resisting a more dangerous enemy of the Polish nation than Russia, which in his view was Germany. A representative of the second group was Józef Piłsudski, a socialist who was born in the Vilna Governorate annexed during the 1795 Third Partition of Poland by the Russian Empire, whose political vision was essentially a far-reaching restoration of the borders of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Because the Russian Empire had collapsed into a state of civil war following the Russian Revolution of 1917, and the Soviet Army had been defeated and been weakened considerably at the end of World War I by Germany's army, resulting in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Piłsudski took the chance and used military force in an attempt to realise his political vision by concentrating on the east and involving himself in the Polish–Soviet War.

الحرب العالمية الثانية

The terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 provided for the partition of Poland along the line of the San, Vistula and Narew rivers which did not go along the Curzon Line but reached far beyond it and awarded the Soviet Union with territories of Lublin and near Warsaw. In September, after the military defeat of Poland, the Soviet Union annexed all territories east of the Curzon Line plus Białystok and Eastern Galicia. The territories east of this line were incorporated into the Byelorussian SSR and Ukrainian SSR after staged referendums and hundreds of thousands of Poles and a lesser number of Jews were deported eastwards into the Soviet Union. In July 1941 these territories were seized by Germany in the course of the invasion of the Soviet Union. During the German occupation most of the Jewish population was deported or killed by the Germans.

In 1944, the Soviet armed forces recaptured eastern Poland from the Germans. The Soviets unilaterally declared a new frontier between the Soviet Union and Poland (approximately the same as the Curzon Line). The Polish government-in-exile in London bitterly opposed this, insisting on the "Riga line". At the Tehran and Yalta conferences between Stalin and the western Allies, the allied leaders Roosevelt and Churchill asked Stalin to reconsider, particularly over Lwów, but he refused. During the negotiations at Yalta, Stalin posed the question "Do you want me to tell the Russian people that I am less Russian than Lord Curzon?"[25] The altered Curzon Line thus became the permanent eastern border of Poland and was recognised by the western Allies in July 1945. The border was later adjusted several times, the biggest revision being in 1951.

When the Soviet Union ceased to exist in 1991, the Curzon Line became Poland's eastern border with Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.

الأعراق شرق خط كرزون حتى 1939

The ethnic composition of these areas proved difficult to measure, both during the interwar period and after World War II. A 1944 article in The Times estimated that in 1931 between 2.2 and 2.5 million Poles lived east of the Curzon Line.[26] According to historian Yohanan Cohen's estimate, in 1939 the population in the territories of interwar Poland east of the Curzon Line gained via the Treaty of Riga totalled 12 million, consisting of over 5 million Ukrainians, between 3.5 and 4 million Poles, 1.5 million Belarusians, and 1.3 million Jews.[27] During World War II, politicians gave varying estimates of the Polish population east of the Curzon Line that would be affected by population transfers. Winston Churchill mentioned "3 to 4 million Poles east of the Curzon Line".[28] Stanisław Mikołajczyk, then Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile, counted this population as 5 million.[29]

Ukrainians and Belarusians if counted together composed the majority of the population of interwar Eastern Poland.[30] The area also had a significant number of Jewish inhabitants. Poles constituted majorities in the main cities (followed by Jews) and in some rural areas, such as Vilnius region or Wilno Voivodeship.[30][31][32]

After the Soviet deportation of Poles and Jews in 1939–1941 (see Polish minority in Soviet Union), The Holocaust and the ethnic cleansing of the Polish population of Volhynia and East Galicia by Ukrainian Nationalists, the Polish population in the territories had decreased considerably. The cities of Wilno, Lwów, Grodno and some smaller towns still had significant Polish populations. After 1945, the Polish population of the area east of the new Soviet-Polish border was in general confronted with the alternative either to accept a different citizenship or to emigrate. According to more recent research, about 3 million Roman Catholic Poles lived east of the Curzon Line within interwar Poland's borders, of whom about 2.1 million[33] to 2.2 million[34] died, fled, emigrated or were expelled to the newly annexed German territories.[35][36] There still exists a big Polish minority in Lithuania and a big Polish minority in Belarus today. The cities of Vilnius, Grodno and some smaller towns still have significant Polish populations. Vilnius District Municipality and Sapotskin region have a Polish majority.

Ukrainian nationalists continued their partisan war and were imprisoned by the Soviets and sent to the Gulag. There they revolted, actively participating in several uprisings (Kengir uprising, Norilsk uprising, Vorkuta uprising).

Polish population east of the Curzon Line before World War II can be estimated by adding together figures for Former Eastern Poland and for pre-1939 Soviet Union:

| 1. پولندا بين الحربين | اللغة الأم البولندية (للكاثوليك) | المصدر (التعداد) | اليوم جزء من: |

|---|---|---|---|

| جنوب شرق بولندا | 2,249,703 (1,765,765)[37] | 1931 Polish census[38] | |

| North-Eastern Poland | 1,663,888 (1,358,029)[39][40] | 1931 Polish census | |

| 2. Interwar USSR | Ethnic Poles according to official census | Source (census) | Today part of: |

| أوكرانيا السوفيتية | 476,435 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| بلاروس السوفيتية | 97,498 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| Soviet Russia | 197,827 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| rest of the USSR | 10,574 | 1926 Soviet census | |

| 3. Interwar Baltic states | Ethnic Poles according to official census | Source (census) | Today part of: |

| Lithuania | 65,599 [Note 1] | 1923 Lithuanian census | |

| Latvia | 59,374 | 1930 Latvian census[41] | |

| Estonia | 1,608 | 1934 Estonian census | |

| TOTAL (1., 2., 3.) | 4 to 5 million ethnic Poles |

أكبر المدن والبلدات

In 1931 according to the Polish National Census, the ten largest cities in the Eastern Borderlands were: Lwów (pop. 312,200), Wilno (pop. 195,100), Stanisławów (pop. 60,000), Grodno (pop. 49,700), Brześć nad Bugiem (pop. 48,400), Borysław (pop. 41,500), Równe (pop. 40,600), Tarnopol (pop. 35,600), Łuck (pop. 35,600) and Kołomyja (pop. 33,800). The ethnolinguistic structure of 22 largest cities was:

| City | Pop. | Polish | Yiddish | Hebrew | German | Ukrainian | Belarusian | Russian | Lithuanian | Other | Today part of: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lwów | 312,231 | 63.5% (198٬212) | 21.6% (67٬520) | 2.5% (7٬796) | 0.8% (2٬448) | 11.3% (35٬137) | 0% (24) | 0.1% (462) | 0% (6) | 0.2% (626) | |

| Wilno | 195,071 | 65.9% (128٬628) | 24.4% (47٬523) | 3.6% (7٬073) | 0.3% (561) | 0.1% (213) | 0.9% (1٬737) | 3.8% (7٬372) | 0.8% (1٬579) | 0.2% (385) | |

| Stanisławów | 59,960 | 43.7% (26٬187) | 34.4% (20٬651) | 3.8% (2٬293) | 2.2% (1٬332) | 15.6% (9٬357) | 0% (3) | 0.1% (50) | 0% (1) | 0.1% (86) | |

| Grodno | 49,669 | 47.2% (23٬458) | 39.7% (19٬717) | 2.4% (1٬214) | 0.2% (99) | 0.2% (83) | 2.5% (1٬261) | 7.5% (3٬730) | 0% (22) | 0.2% (85) | |

| Brześć | 48,385 | 42.6% (20٬595) | 39.3% (19٬032) | 4.7% (2٬283) | 0% (24) | 0.8% (393) | 7.1% (3٬434) | 5.3% (2٬575) | 0% (1) | 0.1% (48) | |

| Borysław | 41,496 | 55.3% (22٬967) | 24.4% (10٬139) | 1% (399) | 0.5% (209) | 18.5% (7٬686) | 0% (4) | 0.1% (37) | 0% (2) | 0.1% (53) | |

| Równe | 40,612 | 27.5% (11٬173) | 50.8% (20٬635) | 4.7% (1٬922) | 0.8% (327) | 7.9% (3٬194) | 0.1% (58) | 6.9% (2٬792) | 0% (4) | 1.2% (507) | |

| Tarnopol | 35,644 | 77.7% (27٬712) | 11.6% (4٬130) | 2.4% (872) | 0% (14) | 8.1% (2٬896) | 0% (2) | 0% (6) | 0% (0) | 0% (12) | |

| Łuck | 35,554 | 31.9% (11٬326) | 46.3% (16٬477) | 2.2% (790) | 2.3% (813) | 9.3% (3٬305) | 0.1% (36) | 6.4% (2٬284) | 0% (1) | 1.5% (522) | |

| Kołomyja | 33,788 | 65% (21٬969) | 19.3% (6٬506) | 0.9% (292) | 3.6% (1٬220) | 11.1% (3٬742) | 0% (0) | 0% (6) | 0% (2) | 0.2% (51) | |

| Drohobycz | 32,261 | 58.4% (18٬840) | 23.5% (7٬589) | 1.2% (398) | 0.4% (120) | 16.3% (5٬243) | 0% (13) | 0.1% (21) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (37) | |

| Pińsk | 31,912 | 23% (7٬346) | 50.3% (16٬053) | 12.9% (4٬128) | 0.1% (45) | 0.3% (82) | 4.3% (1٬373) | 9% (2٬866) | 0% (2) | 0.1% (17) | |

| Stryj | 30,491 | 42.3% (12٬897) | 28.5% (8٬691) | 2.9% (870) | 1.6% (501) | 24.6% (7٬510) | 0% (0) | 0% (10) | 0% (0) | 0% (12) | |

| Kowel | 27,677 | 37.2% (10٬295) | 39.1% (10٬821) | 7.1% (1٬965) | 0.2% (50) | 9% (2٬489) | 0.1% (27) | 7.1% (1٬954) | 0% (1) | 0.3% (75) | |

| Włodzimierz | 24,591 | 39.1% (9٬616) | 35.1% (8٬623) | 8.1% (1٬988) | 0.6% (138) | 14% (3٬446) | 0.1% (18) | 2.9% (724) | 0% (0) | 0.2% (38) | |

| Baranowicze | 22,818 | 42.8% (9٬758) | 38.4% (8٬754) | 2.9% (669) | 0.1% (25) | 0.2% (50) | 11.1% (2٬537) | 4.4% (1٬006) | 0% (1) | 0.1% (18) | |

| Sambor | 21,923 | 61.9% (13٬575) | 22.5% (4٬942) | 1.7% (383) | 0.1% (28) | 13.2% (2٬902) | 0% (4) | 0% (4) | 0% (0) | 0.4% (85) | |

| Krzemieniec | 19,877 | 15.6% (3٬108) | 34.7% (6٬904) | 1.7% (341) | 0.1% (23) | 42.4% (8٬430) | 0% (6) | 4.4% (883) | 0% (2) | 0.9% (180) | |

| Lida | 19,326 | 63.3% (12٬239) | 24.6% (4٬760) | 8% (1٬540) | 0% (5) | 0.1% (28) | 2.1% (414) | 1.7% (328) | 0% (2) | 0.1% (10) | |

| Czortków | 19,038 | 55.2% (10٬504) | 22.4% (4٬274) | 3.1% (586) | 0.1% (11) | 19.1% (3٬633) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (17) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (13) | |

| Brody | 17,905 | 44.9% (8٬031) | 34% (6٬085) | 1% (181) | 0.2% (37) | 19.8% (3٬548) | 0% (5) | 0.1% (9) | 0% (0) | 0.1% (9) | |

| Słonim | 16,251 | 52% (8٬452) | 36.5% (5٬927) | 4.7% (756) | 0.1% (9) | 0.3% (45) | 4% (656) | 2.3% (369) | 0% (2) | 0.2% (35) |

البولنديون شرق خط كرزون بعد الطرد

Despite the expulsion of most ethnic Poles from the Soviet Union between 1944 and 1958, the Soviet census of 1959 still counted around 1.4 million ethnic Poles remaining in the USSR:

| Republic of the USSR | Ethnic Poles in 1959 census |

|---|---|

| Belarusian SSR | 538,881 |

| Ukrainian SSR | 363,297 |

| Lithuanian SSR | 230,107 |

| Latvian SSR | 59,774 |

| Estonian SSR | 2,256 |

| rest of the USSR | 185,967 |

| TOTAL | 1,380,282 |

According to a more recent census, there were about 295,000 Poles in Belarus in 2009 (3.1% of the Belarus population).[42]

الأعراق غرب خط كرزون حتى 1939

According to Piotr Eberhardt, in 1939 the population of all territories between the Oder-Neisse Line and the Curzon Line—all territories which formed post-1945 Poland—totaled 32,337,800 inhabitants, of whom the largest groups were ethnic Poles (approximately 67%), ethnic Germans (approximately 25%), and Jews (2,254,300 or 7%), with 657,500 (2%) Ukrainians, 140,900 Belarusians and 47,000 people of all other ethnic groups also in the region.[43] Much of the Ukrainian population was forcibly resettled after World War II to Soviet Ukraine or scattered in the new Polish Recovered Territories of Silesia, Pomerania, Lubusz Land, Warmia and Masuria in an ethnic cleansing by the Polish military in an operation called Operation Vistula.

انظر أيضاً

- 1893 Afghanistan’s Durand Line

- 1914 India–China McMahon Line

- 1947 India–Pakistan Radcliffe Line

- I Saw Poland Betrayed by Arthur Bliss Lane

- Lewis Bernstein Namier

- Molotov Line

- Oder–Neisse line

- Spa Conference of 1920

- Territorial changes of Poland immediately after World War II

- Zakerzonia

ملاحظات

- ^ Polish sources estimated, based on the percentage of votes for Polish parties in the 1923 Lithuanian parliamentary election, that the real number of ethnic Poles in interwar Lithuania in 1923 was 202,026.

المراجع

- ^ Sarah Meiklejohn Terry (1983). Poland's Place in Europe: General Sikorski and the Origin of the Oder-Neisse Line, 1939-1943. Princeton University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9781400857173.

- ^ Eberhardt, Piotr (2012). "The Curzon line as the eastern boundary of Poland. The origins and the political background". Geographia Polonica. 85 (1): 5–21. doi:10.7163/GPol.2012.1.1.

- ^ R. F. Leslie, Antony Polonsky (1983). The History of Poland Since 1863. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27501-9.

- ^ Rees, Laurence (2009). World War Two Behind Closed Doors, BBC Books, pp.122, 220

- ^ "Modern History Sourcebook: The Yalta Conference, Feb. 1945". Fordham University. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- ^ Henryk Zieliński (1984). "The collapse of foreign authority in the Polish territories". Historia Polski 1914-1939 [History of Poland 1918-1939] (in البولندية). Warsaw: Polish Scientific Publishers PWN. pp. 84–88. ISBN 83-01-03866-7.

- ^ أ ب "Curzon Line | Definition, Facts, & Border | Britannica". www.britannica.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-10-09.

- ^ Zara S. Steiner (2005). The Lights that Failed: European International History, 1919–1933. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822114-2.

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-300-10851-4. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

It also happened to coincide with the eastern limits of pedominantly ethnic Polish territory.

- ^ Aviel Roshwald (2001). Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, Russia, and the Middle East, 1914–1923. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17893-8.

- ^ Joseph Marcus (1983). Social and Political History of the Jews in Poland, 1919–1939. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-3239-6.

- ^ Sandra Halperin (1997). In the Mirror of the Third World: Capitalist Development in Modern Europe. Cornell University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8014-8290-8.

curzon line ethnographic.

- ^ Richard J. Krickus (2002). The Kaliningrad question. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7425-1705-9. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Manfred Franz Boemeke; Manfred F. Boemeke; Gerald D. Feldman; Elisabeth Gläser (1998). The Treaty of Versailles: a reassessment after 75 years. Cambridge University Press. pp. 331–333. ISBN 978-0-521-62132-8. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Arno J. Mayer (26 December 2001). The Furies: Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolutions. Princeton University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-691-09015-3. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ أ ب Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1962). France and her eastern allies, 1919-1925: French-Czechoslovak-Polish relations from the Paris Peace Conference to Locarno. U of Minnesota Press. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-8166-5886-2. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Eric Suy; Karel Wellens (1998). International law: theory and practice : essays in honour of Eric Suy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-90-411-0582-0. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala. "Lecture Notes 11 - THE REBIRTH OF POLAND". University of Kansas. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ E. H. Carr (1982). The Bolshevik Revolution 1917–1923 (A history of Soviet Russia), volume 3 , p.260, Greek edition, ekdoseis Ypodomi

- ^ Michael Palij (1995). The Ukrainian-Polish defensive alliance, 1919-1921: an aspect of the Ukrainian revolution. CIUS Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-895571-05-9. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Henry Butterfield Ryan (19 August 2004). The vision of Anglo-America: the US-UK alliance and the emerging Cold War, 1943-1946. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-521-89284-1. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

A peace was finally concluded and a boundary, much less favourable to Russia than the Curzon Line, was determined at Riga in March 1921 and known as the Riga Line.

- ^ Michael Graham Fry; Erik Goldstein; Richard Langhorne (30 March 2004). Guide to International Relations and Diplomacy. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8264-7301-1. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Spencer Tucker (11 November 2010). Battles That Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-59884-429-0. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Roman Dmowski: La question polonaise. Paris 1909, in French, translated from the Polish 1908 edition of Niemcy, Rosja a sprawa polska (Germany, Russia and the Polish Question, reprinted in 2010 by Nabu Press, U.S.A., ISBN 978-1-141-67057-4).

- ^ Serhii Plokhy (4 February 2010). Yalta: The Price of Peace. Penguin. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-670-02141-3. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ The Times of 12 January 1944; cited according to Alexandre Abramson (Alius): Die Curzon-Line, Europa Verlag, Zürich 1945, p. 45.

- ^ Yohanan Cohen (1989). Small Nations in Times of Crisis and Confrontation. SUNY Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7914-0018-0.

- ^ Winston Churchill (11 April 1986). Triumph and Tragedy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 568. ISBN 978-0-395-41060-8. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ John Erickson (10 June 1999). The road to Berlin. Yale University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-300-07813-8. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ أ ب Anna M. Cienciala. "The foreign policy of Józef Piłsudski and Józef Beck 1926-1939: Misconceptions and interpretations". The Polish Review. Vol. LVI, Nos 1-2. 2011. p. 112.

- ^ Rafal Wnuk. "The Polish underground under Soviet occupation, 1939-1941". Stalin and Europe: Imitation and Domination, 1928-1953. Oxford University Press. 2014. p. 95.

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt, Jan Owsinski (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth Century Eastern Europe: History, Data and Analysis. Routledge. p. 29.

- ^ Kühne, Jörg-Detlef (2007). Die Veränderungsmöglichkeiten der Oder-Neiße-Linie nach 1945 (in الألمانية) (2nd ed.). Baden-Baden: Nomos. see footnote no. 2. ISBN 978-3-8329-3124-7.

- ^ Alexander, Manfred (2008). Kleine Geschichte Polens (in الألمانية) (2nd enlarged ed.). Stuttgart: Reclam. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-15-017060-1.

- ^ Eberhardt, Piotr (2006). Political Migrations in Poland 1939-1948 (PDF). Warsaw: Didactica. ISBN 9781536110357. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-26.

- ^ Eberhardt, Piotr (2011). Political Migrations On Polish Territories (1939-1950) (PDF). Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-83-61590-46-0.

- ^ "Liczba i rozmieszczenie ludności polskiej na części Kresów obecnie w granicach Ukrainy". Konsnard. 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Polish census of 1931".

- ^ "Liczebność Polaków na Kresach w obecnej Białorusi". Konsnard. 2011.

- ^ "Liczba i rozmieszczenie ludności polskiej na obszarach obecnej Litwy". Konsnard. 2011.

- ^ "Third Population and Housing Census in Latvia in 1930 (in Latvian and in French)". State Statistical Office.

- ^ "Population census 2009". belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Eberhardt, Piotr (2000). "Przemieszczenia ludności na terytorium Polski spowodowane II wojną światową" (PDF). Dokumentacja Geograficzna (in البولندية and الإنجليزية). Warsaw. 15: 75–76 – via Repozytorium Cyfrowe Instytutów Naukowych.

المصادر

- Borsody, Stephen. 1993. The New Central Europe. Chapter 10: "Europe's Coming Partition". New York: Boulder. ISBN 0-88033-263-8.

- Byrnes, James F. Speaking Frankly. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1947, pp. 25–32. From the memoirs of James F. Byrnes, on the Yalta Conference.

- Churchill, Winston S. Closing the Ring. 2nd ed. The Second World War Volume 5. London: The Reprint Society Ltd, 1954, pp. 283–285; 314-317. From the memoirs of Winston Churchill.

- Churchill, Winston S. Triumph and Tragedy. 2nd ed. The Second World War Volume 6. London: The Reprint Society Ltd, 1956, pp. 288–292. From the memoirs of Winston Churchill, on the Yalta Conference.

- Crimea Conference, in Parliamentary Debates. 1944–45, No. 408; fifth series, pp. 1274–1284. Winston Churchill's statement to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, 27 February 1945, describing the outcome of the Yalta Conference.

- Nabrdalik, Bart. April 2006. "Hidden Europe-Bieszczady, Poland". Escape from America Magazine. Vol. 8, Issue 3.

- Rogowska, Anna. Stępień, Stanisław. "Polish-Ukrainian Border in the Last Half of the Century" (in پولندية). (The Curzon Line from the historical perspective.)

- Wróbel, Piotr. 2000. "The devil's playground: Poland in World War II". The Wanda Muszynski lecture in Polish studies. Montreal, Quebec: Canadian Foundation for Polish Studies of the Polish Institute of Arts & Sciences.

للاستزادة

- Bohdan, Kordan (1997). "Making Borders Stick: Population Transfer and Resettlement in the Trans-Curzon Territories, 1944–1949". International Migration Review. 31 (3): 704–720. doi:10.2307/2547293. JSTOR 2547293. PMID 12292959.

- Rusin, B., "Lewis Namier, the Curzon Line, and the shaping of Poland's eastern frontier after World War I"

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 البولندية-language sources (pl)

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles using infobox templates with no data rows

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2020

- Articles with پولندية-language sources (pl)

- حدود بلاروس-پولندا

- Eponymous border lines

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- Geographic history of Belarus

- Geographic history of Poland

- Geographic history of Ukraine

- Poland in World War II

- Poland–Soviet Union border

- Poland–Soviet Union relations

- حدود أوكرانيا-پولندا

- Poland–United Kingdom relations

- Second Polish Republic

- Soviet Union–United Kingdom relations

- Western Belorussia (1918–1939)