كونيغسبرغ

كونيگسبرگ

Königsberg | |

|---|---|

| كونيگسبرگ في پروسيا | |

قلعة كونيگسبرگ قبل الحرب العالمية الأولى | |

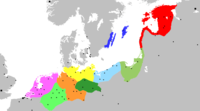

كونيگسبرگ كانت ميناء على الركن الجنوبي الشرقي لـبحر البلطيق. وتُسمى اليوم كاليننگراد. | |

| الإحداثيات: 54°43′00″N 20°31′00″E / 54.71667°N 20.51667°E | |

| بلد سابق: | پروسيا/الرايخ الألماني |

كونيگسبرگ (Königsberg ألمانية: [ˈkøːnɪçsbɛʁk] (![]() listen)) كانت عاصمة شرق پروسيا من العصور الوسطى المتأخرة حتى 1945. أسسها الفرسان التيوتون مباشرة جنوب شبه جزيرة سامبيا في 1255 أثناء الحملات الصليبية الشمالية وسموها على شرف الملك (بالألمانية:König) اوتوكار الثاني من بوهميا[1] (الاسم في اللغة الألمانية Königsberg يعني حرفياً "جبل الملك"). وقد أصبحت المدينة على التتابع عاصمة دولتهم الديرية، دوقية پروسيا، وشرق پروسيا. ميناء البلطيق تطور إلى مركز ثقافي ألماني، فقد كانت مقر لكل من ريتشارد ڤاگنر، إيمانويل كانت، إ. ت. أ. هوفمان ودافيد هيلبرت.

listen)) كانت عاصمة شرق پروسيا من العصور الوسطى المتأخرة حتى 1945. أسسها الفرسان التيوتون مباشرة جنوب شبه جزيرة سامبيا في 1255 أثناء الحملات الصليبية الشمالية وسموها على شرف الملك (بالألمانية:König) اوتوكار الثاني من بوهميا[1] (الاسم في اللغة الألمانية Königsberg يعني حرفياً "جبل الملك"). وقد أصبحت المدينة على التتابع عاصمة دولتهم الديرية، دوقية پروسيا، وشرق پروسيا. ميناء البلطيق تطور إلى مركز ثقافي ألماني، فقد كانت مقر لكل من ريتشارد ڤاگنر، إيمانويل كانت، إ. ت. أ. هوفمان ودافيد هيلبرت.

كونيگسبرگ أصابها ضرر بليغ جراء قصف الحلفاء في 1944 أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية وبعد ذلك احتلها الجيش الأحمر بعد معركة كونيگسبرگ في 1945. المدينة ضمها الاتحاد السوفيتي وفقاً لاتفاقية پوتسدام وأعيد تسكينها بالروس. ولفترة قصيرة ترَوْسَنت لتصبح Кёнигсберг (Kyonigsberg)، ثم تغير اسمها إلى كاليننگراد في 1946 على اسم الزعيم السوفيتي ميخائيل كالينن. المدينة هي الآن عاصمة أوبلاست كاليننگراد في روسيا.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاسم

The first mention of the present-day location in chronicles indicates it as the place of a village of fishermen and hunters. When the Teutonic crusaders began their Baltic Crusades, they built a wooden fortress, and later a stone fortress, calling it "Conigsberg", which later morphed into "Königsberg". The literal meaning of this is 'King's mountain', in apparent honour of King Ottokar II of Bohemia,[2] who led one of the Teutonic campaigns. In Lithuanian, the town is called Karaliaučius (with the same meaning as the German name).[3]

التاريخ

سامبي

Königsberg was preceded by a Sambian, or Old Prussian, fort known as Twangste (Tuwangste, Tvankste), meaning 'Oak Forest',[4] as well as several Old Prussian settlements, including the fishing village and port Lipnick, and the farming villages Sakkeim and Trakkeim.

وصول النظام التيوتوني

During the conquest of the Prussian Sambians by the Teutonic Knights in 1255, Twangste was destroyed and replaced with a new fortress known as Conigsberg. This name meant "King’s Hill" (لاتينية: castrum Koningsberg, Mons Regius, Regiomontium), honoring King Ottokar II of Bohemia, who paid for the erection of the first fortress there during the Prussian Crusade.[5][6] Northwest of this new Königsberg Castle arose an initial settlement, later known as Steindamm, roughly 4.5 miles (7 km) from the Vistula Lagoon.[7]

The Teutonic Order used Königsberg to fortify their conquests in Samland and as a base for campaigns against pagan Lithuania. Under siege during the Prussian uprisings in 1262–63, Königsberg Castle was relieved by the Master of the Livonian Order.[8][9] Because the initial northwestern settlement was destroyed by the Prussians during the rebellion, rebuilding occurred in the southern valley between the castle hill and the Pregel River. This new settlement, Altstadt, received Culm rights in 1286. Löbenicht, a new town directly east of Altstadt between the Pregel and the Schlossteich, received its own rights in 1300. Medieval Königsberg's third town was Kneiphof, which received town rights in 1327 and was located on an island of the same name in the Pregel south of Altstadt.

دوقية پروسيا

براندنبورگ-پروسيا

مملكة پروسيا

By the act of coronation in Königsberg Castle on 18 January 1701, Frederick William's son, Elector Frederick III, became Frederick I, King in Prussia. The elevation of the Duchy of Prussia to the Kingdom of Prussia was possible because the Hohenzollerns' authority in Prussia was independent of Poland and the Holy Roman Empire. Since "Kingdom of Prussia" was increasingly used to designate all of the Hohenzollern lands, former ducal Prussia became known as the Province of Prussia (1701–1773), with Königsberg as its capital. However, Berlin and Potsdam in Brandenburg were the main residences of the Prussian kings.

The city was wracked by plague and other illnesses from September 1709 to April 1710, losing 9,368 people, or roughly a quarter of its populace.[10] On 13 June 1724, Altstadt, Kneiphof, and Löbenicht amalgamated to formally create the larger city Königsberg. Suburbs that subsequently were annexed to Königsberg include Sackheim, Rossgarten, and Tragheim.[7]

الإمبراطورية الروسية

During the Seven Years' War of 1756 to 1763 Imperial Russian troops occupied eastern Prussia at the beginning of 1758. On 31 December 1757, Empress Elizabeth I of Russia issued an ukase about the incorporation of Königsberg into Russia.[11] On 24 January 1758, the leading burghers of Königsberg submitted to Elizabeth.[12] Under the terms of the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (signed 5 May 1762) Russia exited the Seven Years' War, the Russian army abandoned eastern Prussia, and the city reverted to Prussian control.[13]

مملكة بروسيا بعد 1773

After the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Königsberg became the capital of the newly formed province of East Prussia in 1773, which replaced the Province of Prussia in 1773. By 1800 the city was approximately five miles (8.0 km) in circumference and had 60,000 inhabitants, including a military garrison of 7,000, making it one of the most populous German cities of the time.[14]

After Prussia's defeat at the hands of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806 during the War of the Fourth Coalition and the subsequent occupation of Berlin, King Frederick William III of Prussia fled with his court from Berlin to Königsberg.[15] The city was a centre for political resistance to Napoleon. In order to foster liberalism and nationalism among the Prussian middle class, the "League of Virtue" was founded in Königsberg in April 1808. The French forced its dissolution in December 1809, but its ideals were continued by the Turnbewegung of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn in Berlin.[16] Königsberg officials, such as Johann Gottfried Frey, formulated much of Stein's 1808 Städteordnung, or new order for urban communities, which emphasised self-administration for Prussian towns.[17] The East Prussian Landwehr was organised from the city after the Convention of Tauroggen.[18]

In 1819 Königsberg had a population of 63,800.[19] It served as the capital of the united Province of Prussia from 1824 to 1878, when East Prussia was merged with West Prussia. It was also the seat of the Regierungsbezirk Königsberg, an administrative subdivision.[20]

Led by the provincial president Theodor von Schön and the Königsberger Volkszeitung newspaper, Königsberg was a stronghold of liberalism against the conservative government of King Frederick William IV.[21] During the revolution of 1848, there were 21 episodes of public unrest in the city;[22] major demonstrations were suppressed.[23] Königsberg became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the Prussian-led unification of Germany. A sophisticated-for-its-time series of fortifications around the city that included fifteen forts was completed in 1888.[24]

The extensive Prussian Eastern Railway linked the city to Breslau, Thorn, Insterburg, Eydtkuhnen, Tilsit, and Pillau. In 1860 the railway connecting Berlin with St. Petersburg was completed and increased Königsberg's commerce. Extensive electric tramways were in operation by 1900; and regular steamers plied the waterways to Memel, Tapiau and Labiau, Cranz, Tilsit, and Danzig. The completion of a canal to Pillau in 1901 increased the trade of Russian grain in Königsberg, but, like much of eastern Germany, the city's economy was generally in decline.[25] The city was an important entrepôt for Scottish herring. in 1904 the export peaked at more than 322 thousand barrels.[26] By 1900 the city's population had grown to 188,000, with a 9,000-strong military garrison.[7] By 1914 Königsberg had a population of 246,000;[27] Jews flourished in the culturally pluralistic city.[28]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

جمهورية ڤايمار

Following the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I, Imperial Germany was replaced with the democratic Weimar Republic. The Kingdom of Prussia ended with the abdication of the Hohenzollern monarch, Wilhelm II, and the kingdom was succeeded by the Free State of Prussia. Königsberg and East Prussia, however, were separated from the rest of Weimar Germany following the restoration of independent Poland and the creation of the so-called Polish Corridor. Due to the isolated geographical situation after World War I the German Government supported a lot of large infrastructure projects: 1919 Airport "Devenau" (the first civil airport in Germany), 1920 "Deutsche Ostmesse" (a new German trade fare; including new hotels and radio station), 1929 reconstruction of the railway system including the new central railway station and 1930 opening of the North station.

ألمانيا النازية

الدمار في الحرب العالمية الثانية

In 1944, Königsberg suffered heavy damage from British bombing attacks and burned for several days. The historic city center, especially the original quarters Altstadt, Löbenicht, and Kneiphof were destroyed, including the cathedral, the castle, all churches of the old city, the old and the new universities, and the old shipping quarters.[29]

Many people fled from Königsberg ahead of the Red Army's advance after October 1944, particularly after word spread of the Soviet atrocities at Nemmersdorf.[30][31] In early 1945, Soviet forces, under the command of the Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, besieged the city that Hitler had envisaged as the home for a museum holding all the Germans had 'found in Russia'.[32] In Operation Samland, General Baghramyan's 1st Baltic Front, now known as the Samland Group, captured Königsberg in April.[33] Although Hitler had declared Königsberg an "invincible bastion of German spirit", the Soviets captured the city after a three-month-long siege. A temporary German breakout had allowed some of the remaining civilians to escape via train and naval evacuation from the nearby port of Pillau. Königsberg, which had been declared a "fortress" (Festung) by the Germans, was fanatically defended.[34]

On 21 January, during the Red Army's East Prussian Offensive, mostly Polish and Hungarian Jews from Seerappen, Jesau, Heiligenbeil, Schippenbeil, and Gerdauen (subcamps of Stutthof concentration camp) were gathered in Königsberg by the Nazis. Up to 7,000 of them were forced on a death march to Sambia: those that survived were subsequently executed at Palmnicken.[35]

On 9 April – one month before the end of the war in Europe – the German military commander of Königsberg, General Otto Lasch, surrendered the remnants of his forces, following the three-month-long siege by the Red Army. For this act, Lasch was condemned to death, in absentia, by Hitler.[36] At the time of the surrender, military and civilian dead in the city were estimated at 42,000, with the Red Army claiming over 90,000 prisoners.[37] Lasch's subterranean command bunker is preserved as a museum in today's Kaliningrad.[38]

About 120,000 survivors remained in the ruins of the devastated city. The German civilians were held as forced labourers until 1946. Only the Lithuanians, a small minority of the pre-war population, were collectively allowed to stay.[39] Between October 1947 and October 1948, about 100,000 Germans were forcibly moved to Germany.[40]قالب:Quotation needed The remaining 20,000 German residents were expelled in 1949–50.[41]

According to Soviet documents, there were 140,114 German inhabitants in September 1945 in the region that later became the Kaliningrad Oblast, thereof 68,014 in Königsberg. Between April 1947 and May 1951, according to Soviet documents, 102,407 were deported to the Soviet occupation zone of Germany. How many of the deportees were from the city of Königsberg does not become apparent from Soviet records. It is estimated that 43,617 Germans were in the city in the spring of 1946.[42] According to German historian Andreas Kossert, there were about 100,000 to 126,000 German civilians in the city at the time of Soviet conquest, and of these only 24,000 survived to be deported in 1947. Hunger accounted for 75% of the deaths, epidemics (especially typhoid fever) for 2.6% and violence for 15%, according to Kossert.[43]

كاليننگراد السوڤيتية/الروسية

At the Potsdam Conference, northern Prussia, including Königsberg, was annexed by the USSR which attached it to the Russian SFSR. In 1946, the city's name was changed to كاليننگراد. The territory remained part of the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991, and since then has been an exclave of the روسيا الاتحادية.

التعداد السكاني

The vast majority of the population belonged to the Evangelical Church of Prussia. A majority of its parishioners were Lutherans, although there were also Calvinists.

- Number of inhabitants, by year

- 1400: 10,000

- 1663: 40,000

- 1819: 63,869

- 1840: 70,839

- 1855: 83,593

- 1871: 112,092

- 1880: 140,909

- 1890: 172,796

- 1900: 189,483 (including the military), among whom were 8,465 Roman Catholics and 3,975 Jews.[44]

- 1905: 223,770, among whom were 10,320 Roman Catholics, 4,415 Jews and 425 Poles.[45]

- 1910: 245,994

- 1919: 260,895

- 1925: 279,930, among whom were 13,330 Catholics, 4,050 Jews and approximately 6,000 others.[46]

- 1933: 315,794

- 1939: 372,164

- 1945: 73,000

الثقافة ومجتمع كونيگسبرگ

انظر أيضاً

- List of people from Königsberg

- Seven Bridges of Königsberg, a topology problem

- Kaliningrad (Königsberg) question

- Königsberger Paukenhund, traditional kettle drum dog of the Prussian infantry

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المصادر

- أدبيات

- Baedeker, Karl (1904). Baedeker's الأدبGermany. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 395.

- Biskup, Marian. Königsberg gegenüber Polen und dem Litauen der Jagiellonen zur Zeit des Mittelalters (bis 1525) in Królewiec a Polska Olsztyn 1993 (بالألمانية)

- Christiansen, Erik (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 287. ISBN 0-14-026653-4.

- Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard. p. 776. ISBN 067402385-4.

- Gause, Fritz: Die Geschichte der Stadt Königsberg in Preußen. Three volumes, Böhlau, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-412-08896-X (بالألمانية).

- Goettingen Research Committee (1957). German Eastern Territories. Würzburg: Holzner. p. 196.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|otherauthors=ignored (help) - Holborn, Hajo (1964). A History of Modern Germany: 1648-1840. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 556.

- Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1840-1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 844. ISBN 0-691-00797-7.

- Kirby, David (1990). Northern Europe in the Early Modern Period: The Baltic World, 1492-1772. London: Longman. ISBN 0582004101.

- Kirby, David (1999). The Baltic World, 1772-1993: Europe’s Northern Periphery in an Age of Change. London: Longman. ISBN 058200408X.

- Koch, H. W. (1978). A History of Prussia. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 326. ISBN 0-88029-158-3.

- "Juden in Königsberg". Ostpreussen.net. 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2008-03-05. (بالألمانية)

- Seward, Desmond (1995). The Monks of War: The Military Religious Orders. London: Penguin Books. p. 416. ISBN 0-14-019501-7.

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003). Crusader Castles of the Teutonic Knights (1): The red-brick castles of Prussia 1230-1466. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 1-84176-557-0.

- Urban, William (2003). The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. London: Greenhill Books. p. 290. ISBN 1-85367-535-0.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas (2008). Mažosios Lietuvos indėlis į lietuvių kultūrą. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 286. ISBN 9785420016213.

- شهادات كبار السن

- Ludwig Baczko: Versuch einer Geschichte und Beschreibung Königsberg (Trial of a history and of a description of Königsberg). 2nd edition, Königsberg 1804 (in German, online)

- ملاحظات

- ^ Bradbury, Jim (2004). Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. p. 75. ISBN -0-203-64466-2.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRoutledge Companion to Medieval Warfare - ^ "Караляучус - Краловиц - Кёнигсберг - Калининград". Deutsche Welle (in الروسية). 29 April 2005.

- ^ The Monthly Review, p. 609, في كتب گوگل

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbiskup - ^ Koch, Hannsjoachim Wolfgang (1978). A history of Prussia. Longman P4

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةB174 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةseward - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةturnbull - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnorthern13 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhistoria - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةholborn14 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةanthropology - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcomparison - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةkoch15 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةkoch16 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةholborn17 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةclark18 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةholborn19 - ^ Hauf, R (1980) The Prussian administration of the district of Königsberg, 1871-1920, Quelle & Meyer, Wiebelsheim P21

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةclark20 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةclark21 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةholborn22 - ^ "The Past..." Museum of the World Ocean. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbaltic - ^ "Annual Statistics". scottishherringhistory.uk.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbaltic23 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةclark24 - ^ Gilbert, M (1989) Second World War, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, P582-3

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةberlin - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtranslated - ^ Gilbert, M (1989) Second World War, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, P291

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةgenerals - ^ Beevor, A (2002) Berlin: The Downfall 1945 Penguin Books. p. 91.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOst.net - ^ Gilbert, M (1989) Second World War, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, P660

- ^ Hastings, M (2005) 2nd ed Armageddon: The Battle for Germany 1944-45, Pan Macmillan, P291

- ^ "visitkaliningrad.com". visitkaliningrad.com. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ^ Eaton, Nicole. "Building a Soviet City: the Transformation of Königsberg". Wilson Center.

- ^ Berger, Stefan (13 May 2010). "How to be Russian with a Difference? Kaliningrad and its German Past". Geopolitics. 15 (2): 345–366. doi:10.1080/14650040903486967. S2CID 143378878.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةuniversity - ^ Bernhard Fisch and Marina Klemeševa, "Zum Schicksal der Deutschen in Königsberg 1945-1948 (im Spiegel bislang unbekannter russischer Quellen)", Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung Bd. 44 Nr. 3 (1995), pages 394, 395, 399.

- ^ Andreas Kossert, Ostpreuβen. Geschichte und Mythos, 2007 Pantheon Verlag, PDF edition, p. 347. Peter B. Clark (The Death of East Prussia. War and Revenge in Germany’s Easternmost Province, Andover Press 2013, PDF edition, p. 326) refers to Professor Wilhelm Starlinger, the director of the city’s two hospitals that cared for typhus patients, who estimated that out of a population of about 100,000 in April 1945, some 25,000 had survived by the time large-scale evacuations began in 1947. This estimate is also mentioned by Richard Bessel, "Unnatural Deaths", in: The Illustrated Oxford History of World War II, edited by Richard Overy, Oxford University Press 2015, pp. 321 to 343 (p. 336).

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةkonversations - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةgemeindelexikon - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbrockhaus

وصلات خارجية

- Kaliningrad Photo Gallery - Reisebilder aus Königsberg

- The Film Königsberg is dead, France/Germany 2004 by Max & Gilbert (بالألمانية) (إنگليزية)

- Territory's history from 1815 to 1945 (بالألمانية)

- Interactive Map with photos of Königsberg and modern Kaliningrad

- Direct link to photo album from above site

- Site with 400+ side-by-side photos of 1939/2005 identical locations in Königsberg/Kaliningrad (بالروسية) (بالألمانية)

- Northeast Prussia 2000: Travel Photos

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing لتوانية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- تأسيسات 1255

- انحلالات 1946

- أماكن مأهولة تأسست في القرن 13

- كونيگسبرگ

- كاليننگراد

- تاريخ المدن في ألمانيا

- بروسيا الشرقية

- العلاقات الألمانية-السوڤيتية

- أعضاء الرابطة الهانزية

- Kulm law

- 13th century in the State of the Teutonic Order