قيصرية، تركيا

- هذا المقال هو عن قيصري (قيصرية مزاجا) في قپادوقيا. للمواقع الأخرى بنفس الاسم، انظر قيصرية (توضيح).

قيصرية

Kayseri | |

|---|---|

مدينة | |

فوق: ملعب قادر خاص, الثانية من اليسار: شارع سيڤاس، الثاني من اليمين: تمثال أتاتورك وأسوار مدينة قيصرية في الخلفية، الثالثة: حي الأعمال تكين ومنتزه أوتو، أسفل اليسار: قلعة قيصرية ليلاً، أسفل اليمين: Kayseray. | |

| الإحداثيات: 38°44′N 35°29′E / 38.733°N 35.483°E | |

| البلد | |

| المنطقة | وسط الأناضول |

| المحافظة | قيصرية |

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة | مصطفى چلق (AKP) |

| المنسوب | 1٬050 m (3٬440 ft) |

| التعداد (2007) | |

| • الإجمالي | 1٬165٬088 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 38x xx |

| مفتاح الهاتف | (+90) 352 |

| Licence plate | 38 |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.kayseri.bel.tr www.kayseri.gov.tr |

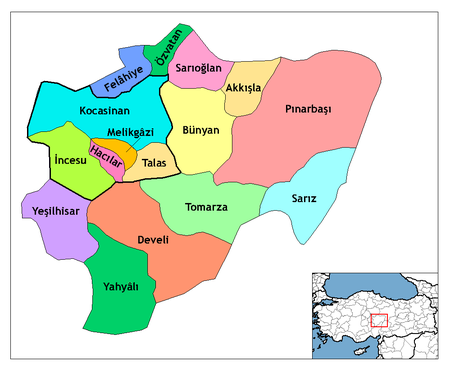

مدينة قيصريه (التركية العثمانية: قیصریه؛ باليونانية: Καισάρεια/Kaisareia؛ اللاتينية: Caesarea Mazaca) هي عاصمة محافظة قيصرية تقع في تركيا ويبلغ تعداد سكانها حوالي 536,392 نسمة. The city of Kayseri, as defined by the boundaries of Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality, is structurally composed of five metropolitan districts, the two core districts of Kocasinan and Melikgazi, and since 2004, also Hacılar, İncesu and Talas.

Kayseri is located at the foot of the inactive volcano Mount Erciyes that towers 3,916 metres (12,848 feet) over the city. The city is often cited in the first ranks among Turkey's cities that fit the definition of Anatolian Tigers.[1]

The city retains a number of historical monuments, including several from the Seljuk period. While it is generally visited en route to the international tourist attractions of Cappadocia, Kayseri has many attractions in its own right: Seljuk and Ottoman era monuments in and around the city centre, Mount Erciyes as a trekking and alpinism centre, Zamantı River as a rafting centre, and the historic sites of Kültepe, Ağırnas, Talas and Develi. Kayseri is served by Erkilet International Airport and is home to Erciyes University.

According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, اعتبارا من 2011[تحديث] the city of Kayseri had a population of 844,656; while Kayseri Province had a population of 1,234,651.[2][3]

أصل الاسم

Kayseri was originally called Mazaka or Mazaca (according to Armenian tradition, it was founded by and named after Mishak)[4] and was known as such to Strabo, during whose time it was the capital of the Roman province of Cilicia, known also as Eusebia at the Argaeus (Εὐσέβεια ἡ πρὸς τῷ Ἀργαίῳ in Greek), after Ariarathes V Eusebes, King of Cappadocia (163–130 BC). The name was changed again by Archelaus (d. 17 AD), last King of Cappadocia (36 BC–14 AD) and a Roman vassal, to "Caesarea in Cappadocia" (to distinguish it from other cities with the name Caesarea in the Roman Empire) in honour of Caesar Augustus, upon his death in 14 AD. This name was rendered as Καισάρεια (Kaisáreia) in Koine Greek, which was the dialect of the later Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire, and that name remained in use by the natives (nowadays known as Cappadocian Greek, due to their spoken language, but then referred to as Rûm, due to their previous Roman citizenship) until their removal from modern Turkey in 1924. (Note that letter C in classical Latin was pronounced K.) When the first Turks arrived in the region in 1080 AD, they adapted this pronunciation, which eventually became Kayseri in Turkish, remaining as such ever since.[5]

التاريخ

التاريخ القديم

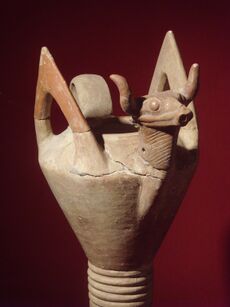

Kültepe, one of the oldest cities in Asia Minor, lies 20 km away.

As Mazaca (باليونانية قديمة: Μάζακα),[6] the city served as the residence of the kings of Cappadocia. In ancient times, it was on the crossroads of the trade routes from Sinope to the Euphrates and from the Persian Royal Road that extended from Sardis to Susa during the over 200 years of Achaemenid Persian rule. In Roman times, a similar route from Ephesus to the East also crossed the city.

The city stood on a low spur on the north side of Mount Erciyes (Mount Argaeus in ancient times). Only a few traces of the ancient site survive in the old town.

العصر الهليني

The city was the centre of a satrapy under Persian rule until it was conquered by Perdikkas, one of the generals of Alexander the Great when it became the seat of a transient satrapy by another of Alexander's former generals, Eumenes of Cardia. The city was subsequently passed to the Seleucid empire after the battle of Ipsus but became once again the centre of an autonomous Greater Cappadocian kingdom under Ariarathes III of Cappadocia in around 250 BC. In the ensuing period, the city came under the sway of Hellenistic influence, and was given the Greek name of Eusebia (باليونانية: Εὐσέβεια) in honor of the Cappadocian king Ariarathes V Eusebes Philopator of Cappadocia (163–130 BC). The new name of Caesarea (باليونانية: Καισάρεια), by which it has since been known, was given to it by the last Cappadocian King Archelaus[5] or perhaps by Tiberius.[7]

الحكم الروماني والبيزنطي

وقعت المدينة تحت الحكم الروماني الرسمي في 17م.

Caesarea was destroyed by the Sassanid king Shapur I after his victory over the Emperor Valerian I in 260 AD. At the time it was recorded to have around 400,000 inhabitants. The city gradually recovered, and became home to several early Christian saints: saints Dorothea and Theophilus the martyrs, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa and Basil of Caesarea. In the 4th century, bishop Basil established an ecclesiastic centre on the plain, about one mile to the northeast, which gradually supplanted the old town.[بحاجة لمصدر] It included a system of almshouses, an orphanage, old peoples' homes, and a leprosarium (leprosy hospital). The city's bishop, Thalassius, attended the [8] Second Council of Ephesus and was suspended from the Council of Chalcedon [9]

A Notitia Episcopatuum composed during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in about 640 lists 5 suffragan dioceses of the metropolitan see of Caesarea. A 10th-century list gives it 15 suffragans.[10] In all the Notitiae Caesarea is given the second place among the metropolitan sees of the patriarchate of Constantinople, preceded only by Constantinople itself, and its archbishops were given the title of protothronos, meaning "of the first see" (after that of Constantinople). More than 50 first-millennium archbishops of the see are known by name, and the see itself continued to be a residential see of the Eastern Orthodox Church until 1923, when by order of the Treaty of Lausanne all members of that Church (Greeks) were deported from what is now Turkey.[11][12][13] Caesarea was also the seat of an Armenian diocese.[14] No longer a residential bishopric, Caesarea in Cappadocia is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see of the Armenian Catholic Church and the Melkite Catholic Church.[15] It was a titular see of the Roman Church under various names as well, including Caesarea Ponti.

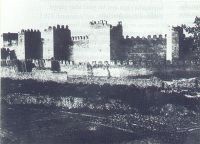

A portion of Basil's new city was surrounded with strong walls, and it was turned into a fortress by Justinian. Caesarea in the 9th century became a Byzantine administrative centre as the capital of the Byzantine Theme of Charsianon. The 1500-year-old Kayseri Castle, built initially by the Byzantines, and expanded by the Seljuks and Ottomans, is still standing in good condition in the central square of the city.

العصر الإسلامي

القائد العربي معاوية فتح قپادوقيا واستولى على قيصرية من البيزنطيين مؤقتاً في 647 م.[16] المدينة سماها العرب قيصرية ولاحقاً قيصري[5] حين استولى عليها لفترة قصيرة السلطان السلجوقي ألپ أرسلان في 1064.[5]The forces of the latter demolished the city and massacred its population.[17] The shrine of Saint Basil was also sacked after the fall of the city.[18] As a result, the city remained uninhabited for the next half century.[17] Later, during 1074–1178 the area came under the control of the Danishmendids and rebuilt the city in 1134.[19] The Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate controlled the city during the period 1178–1243 and became one of their most prominent centers, until it fell to the Mongols in 1243. Within the walls lies the greater part of Kayseri, rebuilt between the 13th and 16th centuries. Kayseri was successively ruled by Eretnids. The city finally became Ottoman in 1515. It was sanjak center initially in Rum Eyalet (1515–1521), finally in Ankara Vilayet (Founded as Bozok Eyalet) (1839–1923).

Thus, there were three golden-age periods for Kayseri. The first, dating to 2000 BC, was when the city was a trade post between the Assyrians and the Hittites. The second golden age came during the Roman rule (1st to 11th centuries). The third golden age was during the reign of Seljuks (1178–1243), when the city was the second capital of the state. The short-lived Seljuk rule left a large number of historic landmarks; historic buildings such as the Hunat Hatun Complex, Kilij Arslan Mosque, The Grand Mosque and Gevher Nesibe Hospital.

الجغرافيا

المناخ

Kayseri has a cold semi-arid climate, Köppen climate classification (BSk) with cold, snowy winters and hot, dry summers with cool nights due to Kayseri's high elevation. Rainfall occurs mostly during the spring, early summer and late autumn.

| Climate data for قيصرية (1931–2017) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

40.7 (105.3) |

40.6 (105.1) |

36.0 (96.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

40.7 (105.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

17.4 (63.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.8 (19.8) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −32.5 (−26.5) |

−31.2 (−24.2) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−20.7 (−5.3) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−32.5 (−26.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35.3 (1.39) |

36.1 (1.42) |

41.9 (1.65) |

51.8 (2.04) |

51.9 (2.04) |

39.6 (1.56) |

9.4 (0.37) |

6.8 (0.27) |

13.7 (0.54) |

27.9 (1.10) |

32.5 (1.28) |

37.4 (1.47) |

384.3 (15.13) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.2 | 11.3 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 8.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 11.9 | 104.9 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 36 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 72 | 62 | 58 | 56 | 50 | 44 | 44 | 47 | 58 | 69 | 77 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 93.0 | 113.0 | 148.8 | 186.0 | 254.2 | 309.0 | 368.9 | 350.3 | 273.0 | 207.7 | 144.0 | 93.0 | 2٬540٫9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 10.3 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 9.1 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 6.9 |

| Source 1: Turkish State Meteorological Service[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather2[21] | |||||||||||||

التقسيمات الادارية

The city of Kayseri consists of the following metropolitan districts:

| الاسم |

|---|

| Akkışla |

| بنيان |

| دولي |

| فلاحية |

| Hacılar |

| İncesu |

| Kocasinan |

| Melikgâzi |

| Özvatan |

| Sarıoğlan |

| Sarız |

| Talas |

| Tomarza |

| Yahyâlı |

| يشيلحصار |

المواصلات

مطبخ قيصرية

Kayseri is renowned for its culinary specialities such as mantı, pastırma and sucuk. Mantı is the most popular dish in Kayseri for the local people and tourists. Another speciality is stuffed zucchini flowers made with Köfte, garlic and spices. Nevzine is a traditional dessert.

أعلام قيصرية

(بالترتيب الأبجدي)

- عبد الله گول - Turkey's current president

- أحمد شاپيرو-إرجياس- Turkish American لاعب شطرنج

- أرسطوطل اوناسيس - Greek shipping magnate born in إزمير to a family from Kayseri

- باسل من قيصرية - Byzantine theologian (one of the الآباء الكپادوقيون)

- أسرة باليان - is a dynasty of famous عثمانيين imperial architects of Armenian ethnicity

- ذكران كلكيان - Armenian a notable collector and dealer of Islamic art

- إليا كازان - Greek American movie director

- فاتح سولاك - Turkish international basketball player

- جوهر نسيبه - Seljuk princess who endowed the city's landmark 13th century medical center (دار الشفاء)

- گريگوري المصور - مؤسس الكنيسة الأرمنية

- Gregory of Nyssa - brother of Basil of Caesarea, also a Byzantine theologian, one of the الآباء الكپادوقيون

- Göksel Arsoy - Turkish movie star

- هاگوپ كڤوركيان - جامع تحف أرمني

- حسن سامي بولاق - Turkish writer, poet

- İsmet Özel -Turkish poet

- Kadir Has - Turkish business tycoon

- لطيفة تكين - Turkish author

- متين كاچان - Turkish writer

- معمار سنان - Ottoman-period architect

- مصطفى إسلاماوغلو - Turkish writer

- نسرين ناس - Turkish politician

- Orhan Delibaş - Turkish Dutch boxer

- ريحان كاراجا - Turkish singer

- Romanos IV Diogenes - Byzantine General and later Emperor (1068-1071)

- Theodoros Alyatis - Byzantine General of the Cappadocian Thema, fought alongside the Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at the Battle of Manzikert(1071).

العلاقات الدولية

المدن الشقيقة

قيصرية متوأمة مع:

|

أوروپا |

آسيا |

صور من قيصرية

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ ESI. "Islamic Calvinists: Change and Conservatism in Central Anatolia" (PDF). European Stability Initiative, Berlin. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-12-10. Retrieved 2005-09-19.

- ^ "2011". citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Olmstead, A.T. (1929), Two Stone Idols from Asia Minor at the University of Illinois. pp. 313. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/4236961?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3Aeb2f654f8d09b7b6fd30f32d7d1679fa&seq=4#page_scan_tab_contents)

- ^ أ ب ت ث Everett-Heath, John (2005). "Kayseri". Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ^ Strabo, Geography, § 12.2.7

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Caesarea". Archived from the original on 2007-07-02.

- ^ Richard Price, Michael Gaddis The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, Volume 1 p31.

- ^ Richard Price, Michael Gaddis, The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon, Volume 1 p36.

- ^ Heinrich Gelzer, Ungedruckte und ungenügend veröffentlichte Texte der Notitiae episcopatuum, in: Abhandlungen der philosophisch-historische classe der bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1901, p. 536, nº 77–82, and pp. 551–552, nnº 106–121.

- ^ Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae Archived 2015-03-08 at Wikiwix, Leipzig 1931, p. 440

- ^ Michel Lequien, Oriens christianus in quatuor Patriarchatus digestus, Paris 1740, Vol. I, coll. 367–390

- ^ Raymond Janin, v. 2. Césarée de Cappadoce, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques, vol. XII, Paris 1953, coll. 199–203

- ^ "Caesarea". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02.

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 867

- ^ Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1969. Pg 116.

- ^ أ ب Ash, John (2006). A Byzantine journey ([2. ed.] ed.). London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 167. ISBN 9781845113070.

In that year the Turks captured Caesarea, the chief city of eastern Cappadocia, burnt it to the ground, massacred its inhabitants and descrated the great shrine of Saint Basil.

- ^ Vaughan, Louis Bréhier ; translated by Margaret (1977). The life and death of Byzantium. Amsterdam: North-Holland Pub. Co . p. 193. ISBN 9780720490084.

In the spring of 1067 he invaded the Pontus and penetrated as far as Caesarea in Cappadocia which he demolished

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Speros Vryonis, The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century' Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine (University of California Press, 1971), p. 155

- ^ "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Genel İstatistik Verileri" (in التركية). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ "December Climate History for Kayseri | Local | Turkey". Myweather2.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ "Mostar Gradovi prijatelji" [Mostar Twin Towns]. Grad Mostar [Mostar Official City Website] (in البوسنية). Archived from the original on 2013-11-06. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- ^ http://www.nation.com.pk/pakistan-news-newspaper-daily-english-online/Regional/Lahore/15-Jan-2010/Punjab-Turkey-sign-four-MoUs[dead link]

وصلات خارجية

- Official Government Web Site

- Dick Osseman. Photographs: "Kayseri".

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - = Gessaria Armenian history and presence in Kayseri/Gessaria

- The Armenian church of St. Gregory in Kayseri

- ESI report: Islamic Calvinists. Change and conservatism in central Anatolia (19 September 2005)

| الترتيب | المحافظة | التعداد | الترتيب | المحافظة | التعداد | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

إسطنبول  أنقرة |

1 | إسطنبول | إسطنبول | 13,820,334 | 11 | قيصرية | قيصرية | 880,255 |  إزمير  بورصة |

| 2 | أنقرة | أنقرة | 4,474,305 | 12 | إسكيشهر | إسكيشهر | 670,544 | ||

| 3 | إزمير | إزمير | 2,828,927 | 13 | گبزه | خوجةإلي | 582,352 | ||

| 4 | بورصة | بورصة | 1,769,752 | 14 | شانلياورفا | شانلياورفا | 551,511 | ||

| 5 | أضنة | أضنة | 1,645,965 | 15 | دنيزلي | دنيزلي | 540,000 | ||

| 6 | غازيعنتپ | غازيعنتپ | 1,465,019 | 16 | سمسون | سمسون | 523,192 | ||

| 7 | قونية | قونية | 1,138,609 | 17 | كهرمانمراش | كهرمانمراش | 458,628 | ||

| 8 | أنطاليا | أنطاليا | 1,027,551 | 18 | آداپازاری | ساكاريا | 449,290 | ||

| 9 | ديار بكر | ديار بكر | 906,013 | 19 | ملاطية | ملاطية | 425,000 | ||

| 10 | مرسين | مرسين | 898,813 | 20 | أرضروم | أرضروم | 381,104 | ||

- ^ http://www.citypopulation.de/Turkey-RBC20.html December 2013 address-based حساب المعهد الإحصائي التركي مقدم من citypopulation.de

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Webarchive template other archives

- CS1 التركية-language sources (tr)

- CS1 البوسنية-language sources (bs)

- Articles with dead external links from December 2017

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2011

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2019

- CS1 errors: URL

- أقضية قيصرية

- منطقة وسط الأناضول

- مواقع أثرية في تركيا

- قپادوقيا

- قيصرية

- مواقع رومانية في تركيا

- محافظة قيصرية

- مدن تركيا