قناة پنما

| Panama Canal Canal de Panamá | |

|---|---|

A schematic of the Panama Canal, illustrating the sequence of locks and passages | |

| المواصفات | |

| الطول | 82 km (51 ميل) |

| أقصى طول للسفينة | 366 m (1،200 ft 9 in) |

| أكبر عارضة سفينة | 49 m (160 ft 9 in) (originally 28.5 m أو 93 ft 6 in) |

| أقصى غاطس سفينة | 15.2 m (50 ft) |

| الأهوسة | 3 locks up, 3 down per transit; all three lanes (3 lanes of locks) |

| الوضع | Open, expansion opened June 26, 2016 |

| سلطة الملاحة | Panama Canal Authority |

| التاريخ | |

| المهندس الرئيسي | Ferdinand de Lesseps, John Findley Wallace (1904–1905), John Frank Stevens (1905–1907), George Washington Goethals (1907–1914) |

| بدء الإنشاء | مايو 4, 1904 |

| تاريخ الاكتمال | أغسطس 15, 1914 |

| تاريخ التمديد | يونيو 26, 2016 |

| الجغرافيا | |

| نقطة البداية | Atlantic Ocean |

| نقطة النهاية | Pacific Ocean |

| تتصل بـ | Pacific Ocean from Atlantic Ocean and vice versa |

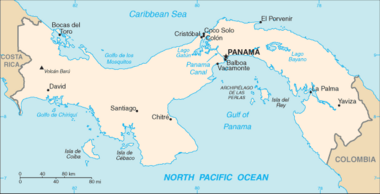

قناة پنما (إسپانية: Canal de Panamá) هي 77-كيلومتر (48 mi)، هي قناة سفن في پنما، تصل بين المحيط الأطلنطي والمحيط الهادي وتعتبر ممر رئيسي للتجارة البحرية العالمية. أنشئت القناة ما بين عام 1904 و1914، وصل عدد السفن المار بها من 1000 إلى 14.702 سفينة سنويا في عام 2008، بإجمالي حمولة 309.6 مليون طن. Canal locks at each end lift ships up to Gatun Lake, an artificial freshwater lake 26 متر (85 ft) above sea level, created by damming up the Chagres River and Lake Alajuela to reduce the amount of excavation work required for the canal, and then lower the ships at the other end. An average of 200،000،000 L (52،000،000 US gal) of fresh water are used in a single passing of a ship.

The Panama Canal shortcut greatly reduces the time for ships to travel between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, enabling them to avoid the lengthy, hazardous route around the southernmost tip of South America via the Drake Passage or Strait of Magellan. It is one of the largest and most difficult engineering projects ever undertaken.

Colombia, France, and later the United States controlled the territory surrounding the canal during construction. France began work on the canal in 1881, but stopped because of lack of investors' confidence due to engineering problems and a high worker mortality rate. The United States took over the project in 1904 and opened the canal in 1914. The US continued to control the canal and surrounding Panama Canal Zone until the Torrijos–Carter Treaties provided for its handover to Panama in 1977. After a period of joint American–Panamanian control, the canal was taken over by the Panamanian government in 1999. It is now managed and operated by the Panamanian government-owned Panama Canal Authority.

The original locks are 33.5 متر (110 ft) wide. A third, wider lane of locks was constructed between September 2007 and May 2016. The expanded waterway began commercial operation on June 26, 2016. The new locks allow transit of larger, NeoPanamax ships.

Annual traffic has risen from about 1,000 ships in 1914, when the canal opened, to 14,702 vessels in 2008, for a total of 333.7 million Panama Canal/Universal Measurement System (PC/UMS) tons. By 2012, more than 815,000 vessels had passed through the canal.[1] In 2017, it took ships an average of 11.38 hours to pass between the canal's two outer locks. The American Society of Civil Engineers has ranked the Panama Canal one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World.[2] The canal is threatened by low water levels during drought and due to climate change.

التاريخ

المقترحات المبكرة في پنما

أنشأت قناة بنما من قبل الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية بين عامي 1904 و1914 لتصل المحيط الأطلنطي بالمحيط الهادي. والقناة تقسم جمهورية بنما إلى جزئين شرقي وغربي، يبلغ طول القناة 80 كم. في 7 مايو عام 1914 م عبرت أول باخرة القناة.

استوجب استخدام نواظم ومراكز تحكم خاصة، يرتفع قاعها أكثر من 25 م عن مستوى سطح البحر وتجتازها سفن ذات أبعاد محددة.

في 1 أغسطس 1902 اشترت أمريكا حقوق قناة بنما من الفرنسيين، حيث كان الفرنسيون هم من كلفوا أولا بشق هذه القناة، إلا أن المشروع الفرنسي تعطل لأسباب عديدة منها طريقة تصميم المشروع، فقام الأمريكيون بالمشروع في تصميم آخر معتمدين فيه على مبدأ بناية السدود على نهر تشاجرز Chagers.

خضعت منطقة القناة للولايات المتحدة الأمريكية بموجب اتفاقية بين البلدين بدأت من سنة 1978 م وانتهت سنة 1999 م. استعادت جمهورية بنما سيادتها على القناة بعد إدارة الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية لها 85 عاما. يمر في قناة بنما أربعة عشر ألف سفينة سنوياً.

لجنة القناة البرزخية

التخطيط وبداية الانشاء

التطورات الأخيرة

الأهمية الملاحية لقناة پنما

تُعد قناة پنما أحد أهم الممرات المائية في العالم، حيث تصل القناة بين المحيط الأطلسي والمحيط الهادي بطول يتجاوز حوالي 80 كم، وقد بدأت أول محاولة لبناء قناة بنما في عام 1880 تحت القيادة الفرنسية، ولكن تم التخلي عن بنائها عام 1883 بعد أن توفي حوالي 22 ألفًا من عمال بنائها، وذلك بسبب تفشي الأمراض الوبائية والانهيارات الأرضية.

وعقب فشل الجهود الفرنسية بدأت الولايات المتحدة جهدًا حثيثًا في تأسيس القناة بعد موافقة الكونگرس الأمريكي عام 1903 على المشروع، على مدار عشر سنوات بتكلفة بلغت 380 مليون دولار أمريكي تقريبًا حتى تم افتتاح القناة في عام 1914، وقد خضعت منطقة القناة لسيادة الولايات المتحدة بموجب اتفاقية بين الولايات المتحدة وبنما بدأت من عام 1978 وانتهت سنة 1999، حيث استعادت جمهورية بنما سيادتها على القناة بعد إدارة الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية لها 85 عامًا.

وقد شكل فتح قناة بنما ثورة في التجارة العالمية، فقد سمح للولايات المتحدة بنقل أسطولها العسكري والتجاري من ساحل إلى آخر من خلال تقصير المسافة بين مدينتي نيويورك وسان فرانسيسكو إلى أقل من 8370 كم، كما أصبحت ممرًّا أساسيًّا للمبادلات التجارية بين أوروبا وأمريكا اللاتينية وآسيا، حيث يمر منها ما يعادل 5% من التجارة البحرية العالمية.

ويمر كل عام بين ضفتي قناة بنما حوالي 14 ألف سفينة تتوجه إلى حوالي 1700 ميناء في حوالي 160 دولة حول العالم، وفي السياق ذاته تمثل قناة بنما بعدًا استراتيجيًّا مهمًّا للولايات المتحدة، لأن 70% من السفن التي تعبر قناة بنما سنويًّا تتجه إلى موانئ ولايات الساحل الشرقي للولايات المتحدة، كما تمثل قناة بنما مصدرًا مهمًّا رئيسيًّا للنقد الأجنبي لدولة بنما، حيث تدر عليها ما يقرب من 2,4 مليار دولار سنويًّا.

القنال

التصميم

| قناة پنما | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While globally the Atlantic Ocean is east of the isthmus and the Pacific is west, the general direction of the canal passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific is from northwest to southeast, because of the shape of the isthmus at the point the canal occupies. The Bridge of the Americas (إسپانية: Puente de las Américas) at the Pacific side is about a third of a degree east of the Colón end on the Atlantic side.[4] Still, in formal nautical communications, the simplified directions "southbound" and "northbound" are used.

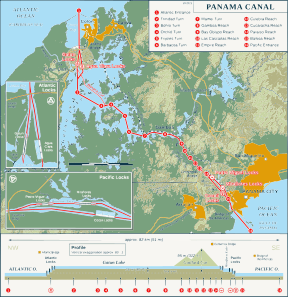

The canal consists of artificial lakes, several improved and artificial channels, and three sets of locks. An additional artificial lake, Alajuela Lake (known during the American era as Madden Lake), acts as a reservoir for the canal. The layout of the canal as seen by a ship passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific is:[5]

- From the formal marking line of the Atlantic Entrance, one enters Limón Bay (Bahía Limón), a large natural harbor. The entrance runs 8.9 km (5+1⁄2 mi). It provides a deepwater port (Cristóbal), with facilities like multimodal cargo exchange (to and from train) and the Colón Free Trade Zone (a free port).

- A 3.2 km (2 mi) channel forms the approach to the locks from the Atlantic side.

- The Gatun Locks, a three-stage flight of locks 2.0 km (1+1⁄4 mi) long, lifts ships to the Gatun Lake level, some 27 m (87 ft) above sea level.

- Gatun Lake, an artificial lake formed by the building of the Gatun Dam, carries vessels 24 km (15 mi) across the isthmus. It is the summit canal stretch, fed by the Gatun River and emptied by basic lock operations.

- From the lake, the Chagres River, a natural waterway enhanced by the damming of Gatun Lake, runs about 8.4 km (5+1⁄4 mi). Here the upper Chagres River feeds the high-level-canal stretch.

- The Culebra Cut slices 12.5 km (7+3⁄4 mi) through the mountain ridge, crosses the continental divide and passes under the Centennial Bridge.

- The single-stage Pedro Miguel Lock, which is 1.4 km (7⁄8 mi) long, is the first part of the descent with a lift of 9.4 m (31 ft).

- The artificial Miraflores Lake 1.8 km (1+1⁄8 mi) long, and 16 m (54 ft) above sea level.

- The two-stage Miraflores Locks is 1.8 km (1+1⁄8 mi) long, with a total descent of 16 m (54 ft) at mid-tide.

- From the Miraflores Locks one reaches Balboa harbor, again with multimodal exchange provision (here the railway meets the shipping route again). Nearby is Panama City.

- From this harbor an entrance/exit channel leads to the Pacific Ocean (Gulf of Panama), 13.3 km (8+1⁄4 mi) from the Miraflores Locks, passing under the Bridge of the Americas.

Thus, the total length of the canal is 80 km (50 mi). In 2017 it took ships an average of 11.38 hours to pass between the canal's two outer locks.[6]

الملاحة

بحيرة گاتون

Created in 1913 by damming the Chagres River, the Gatun Lake is a key part of the Panama Canal, providing the millions of liters of water necessary to operate its locks each time a ship passes through. At time of formation, Gatun Lake was the largest human-made lake in the world.

مقاس الهويس

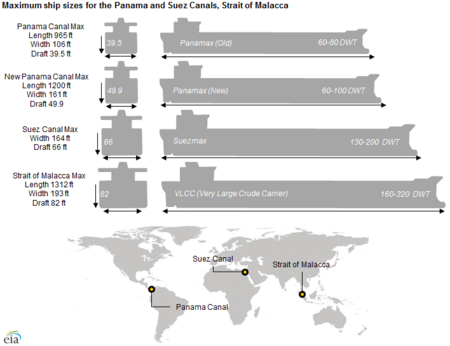

Because of the importance of the canal to international trade, many ships are built to the maximum size allowed.

For its first century, the width and length of ships that may transit the canal was limited by the Pedro Miguel Locks; their draft by the canal's minimum 12.6 m (41.2 ft) depth; and their height by the main span of the Bridge of the Americas at Balboa. Ships built to those limits are known as Panamax vessels. A Panamax cargo ship typically has a deadweight tonnage (DWT) of 65,000–80,000 tons, but its actual cargo is restricted to about 52,500 tons because of the canal's draft restrictions within the canal.[7] The longest ship ever to transit the canal was the San Juan Prospector (now Marcona Prospector), an ore-bulk-oil carrier that is 296.57 m (973 ft) long with a beam of 32.31 m (106 ft).[8]

Initially the locks at Gatun were designed to be 28.5 m (94 ft) wide. In 1908, the United States Navy requested that the width be increased to at least 36 m (118 ft) to allow the passage of large warships. A compromise was made and the locks were built 33.53 m (110.0 ft) wide. Each lock is 320 m (1،050 ft) long, with the walls ranging in thickness from 15 m (49 ft) at the base to 3 m (9.8 ft) at the top. The central wall between the parallel locks at Gatun is 18 m (59 ft) thick and over 24 m (79 ft) high. The steel lock gates measure an average of 2 m (6.6 ft) thick, 19.5 m (64 ft) wide, and 20 m (66 ft) high.[9]

Panama Canal pilots were initially unprepared to handle the flight decks of aircraft carriers, which protrude beyond the hull on either side of the ship. When يوإسإس Saratoga made her first trip through the Gatun Locks in 1928, the ship knocked over all the concrete lamp posts along the canal.[10]

In 2016, a decade-long expansion project created larger locks, allowing bigger ships to transit through deeper and wider channels.[11] The allowed dimensions of ships using these locks increased by 25 percent in length, 51 percent in beam, and 26 percent in draft, as defined by New Panamax metrics.[12]

الرسوم

As with a toll road, vessels transiting the canal must pay tolls. Tolls for the canal are set by the Panama Canal Authority and are based on vessel type, size, and the type of cargo.[13]

For container ships, the toll is assessed on the ship's capacity expressed in twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), one TEU being the size of a standard intermodal shipping container. Effective April 1, 2016, this toll went from US$74 per loaded container to $60 per TEU capacity plus $30 per loaded container for a potential $90 per TEU when the ship is full. A Panamax container ship may carry up to 4,400 TEU. The toll is calculated differently for passenger ships and for container ships carrying no cargo ("in ballast"). اعتبارا من 1 أبريل 2016[تحديث], the ballast rate is US$60, down from US$65.60 per TEU.

Passenger vessels in excess of 30,000 tons (PC/UMS) pay a rate based on the number of berths, that is, the number of passengers that can be accommodated in permanent beds. Since April 1, 2016, the per-berth charge is $111 for unoccupied berths and $138 for occupied berths in the Panamax locks. Starting in 2007, this fee has greatly increased the tolls for such ships.[14] Passenger vessels of less than 30,000 tons or less than 33 tons per passenger are charged according to the same per-ton schedule as are freighters. Almost all major cruise ships have more than 33 tons per passenger; the rule of thumb for cruise line comfort is generally given as a minimum of 40 tons per passenger.

Most other types of vessels pay a toll per PC/UMS net ton, in which one "ton" is actually a volume of 100 أقدام مكعبة (2.83 m3). (The calculation of tonnage for commercial vessels is quite complex.) As of fiscal year 2016[تحديث], this toll is US$5.25 per ton for the first 10,000 tons, US$5.14 per ton for the next 10,000 tons, and US$5.06 per ton thereafter. As with container ships, reduced tolls are charged for freight ships "in ballast", $4.19, $4.12, $4.05 respectively.

On 1 April 2016, a more complicated toll system was introduced, having the neopanamax locks at a higher rate in some cases, natural gas transport as a new separate category and other changes.[15] As of October 1, 2017, there are modified tolls and categories of tolls in effect.[16] Small (less than 125 ft) vessels up to 583 PC/UMS net tons when carrying passengers or cargo, or up to 735 PC/UMS net tons when in ballast, or up to 1,048 fully loaded displacement tons, are assessed minimum tolls based upon their length overall, according to the following table (as of 29 April 2015):

| طول السفينة | الرسوم |

|---|---|

| Up to 15.240 متر (50 ft) | US$800 |

| From 15.240 إلى 24.384 متر (50 إلى 80 ft) | US$1,300 |

| From 24.384 إلى 30.480 متر (80 إلى 100 ft) | US$2,000 |

| More than 30.480 متر (100 ft) | US$3,200 |

| INTRA MARITIME CLUSTER – Local Tourism More than 24.384 متر (80 ft) |

US$2,000 plus $72/TEU |

Morgan Adams of Los Angeles, California, holds the distinction of paying the first toll received by the U.S. government for the use of the Panama Canal by a pleasure boat. His boat Lasata passed through the Zone on August 14, 1914. The crossing occurred during a 10،000-كيلومتر (6،000-ميل) sea voyage from Jacksonville, Florida, to Los Angeles in 1914.[17]

The most expensive regular toll for canal passage to date was charged on April 14, 2010, to the cruise ship Norwegian Pearl, which paid US$375,600.[18][19] The average toll is around US$54,000. The highest fee for priority passage charged through the Transit Slot Auction System was US$220,300, paid on August 24, 2006, by the Panamax tanker Erikoussa,[20] bypassing a 90-ship queue waiting for the end of maintenance work on the Gatun Locks, and thus avoiding a seven-day delay. The normal fee would have been just US$13,430.[21]

The lowest toll ever paid was 36 cents (equivalent to $4٫87 in 2022), by American Richard Halliburton who swam the Panama Canal in 1928.[22]

قضايا أدت إلى التوسع

الكفاءة والصيانة

Opponents to the 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaties feared that efficiency and maintenance would suffer following the U.S. withdrawal from the Panama Canal Zone; however, this has been proven not to be the case. In 2004, it was reported that canal operations, capitalizing on practices developed during the American administration, were improving under Panamanian control.[23] Canal Waters Time (CWT), the average time it takes a vessel to navigate the canal, including waiting time, is a key measure of efficiency; in the first decade of the 2000s, it ranged between 20 and 30 hours, according to the ACP. The accident rate has also not changed appreciably in the past decade, varying between 10 and 30 accidents each year from about 14,000 total annual transits.[24][25][26] An official accident is one in which a formal investigation is requested and conducted.

Increasing volumes of imports from Asia, which previously landed on US West Coast ports, are now passing through the canal to the American East Coast.[27] The total number of ocean-going transits increased from 11,725 in 2003 to 13,233 in 2007, falling to 12,855 in 2009. (The canal's fiscal year runs from October through September.)[28] This has been coupled with a steady rise in average ship size and in the numbers of Panamax vessels passing through the canal, so that the total tonnage carried rose from 227.9 million PC/UMS tons in fiscal year 1999 to a then record high of 312.9 million tons in 2007, and falling to 299.1 million tons in 2009.[4][28] Tonnage for fiscal 2013, 2014 and 2015 was 320.6, 326.8 and 340.8 million PC/UMS tons carried on 13,660, 13,481 and 13,874 transits respectively.[29]

In the first decade after the transfer to Panamanian control, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) invested nearly US$1 billion in widening and modernizing the canal, with the aim of increasing capacity by 20 percent.[30] The ACP cites a number of major improvements, including the widening and straightening of the Culebra Cut to reduce restrictions on passing vessels, the deepening of the navigational channel in Gatun Lake to reduce draft restrictions and improve water supply, and the deepening of the Atlantic and Pacific entrances to the canal. This is supported by new equipment, such as a new drill barge and suction dredger, and an increase of the tug boat fleet by 20 percent. In addition, improvements have been made to the canal's operating machinery, including an increased and improved tug locomotive fleet, the replacement of more than 16 km (10 mi) of locomotive track, and new lock machinery controls. Improvements have been made to the traffic management system to allow more efficient control over ships in the canal.[31]

In December 2010, record-breaking rains caused a 17-hour closure of the canal; this was the first closure since the United States invasion of Panama in 1989.[32][33] The rains also caused an access road to the Centenario Bridge to collapse.[34][35][36][37]

السعة

The canal handles more vessel traffic than had ever been envisioned by its builders. In 1934 it was estimated that the maximum capacity of the canal would be around 80 million tons per year;[38] as noted above, canal traffic in 2015 reached 340.8 million tons of shipping.

To improve capacity, a number of improvements have been made to maximize the use of the locking system:[39]

- Implementation of an enhanced locks lighting system;

- Construction of two tie-up stations in Culebra Cut;

- Widening Culebra Cut from 192 إلى 218 متر (630 إلى 715 ft);

- Improvements to the tugboat fleet;

- Implementation of the carousel lockage system in Gatun locks;

- Development of an improved vessel scheduling system;

- Deepening of Gatun Lake navigational channels from 10.4 إلى 11.3 متر (34 إلى 37 ft) PLD;

- Modification of all locks structures to allow an additional draft of about 0.30 متر (1 ft);

- Deepening of the Pacific and Atlantic entrances;

- Construction of a new spillway in Gatun, for flood control.

These improvements enlarged the capacity from 300 million PCUMS (2008) to 340 PCUMS (2012). These improvements were started before the new locks project, and are complementary to it.

المنافسة

يختلف الوزن النسبي لأهمية كلٍّ من قناة بنما وقناة السويس بالنسبة للربط بين المناطق الجغرافية المختلفة، حيث تمثل قناة السويس أهمية محورية بالنسبة لحاملات النفط من الخليج العربي إلى أوروبا، وكذلك في الربط بين جنوب شرق آسيا وأوروبا، وبين شرق إفريقيا والدول العربية، في حين تتميز قناة بنما بملاءمتها الجغرافية في تدفق التجارة بين اليابان وأستراليا ودول أمريكا الجنوبية والساحل الشرقي لأمريكا. إلا أنه من ناحية أخرى تبرز المنافسة بين قناة السويس وقناة بنما حول نقل البضائع بين آسيا وأمريكا الشمالية خاصة ولايات الساحل الشرقي، حيث توجد ثلاثة طرق رئيسية تربط بين المنطقتين هي: قناة بنما، وقناة السويس، بالإضافة إلى الطريق الملاحي عبر المحيط الهادئ المرتبط بنظام النقل متعدد الوسائط عبر الولايات المتحدة وكندا. حيث تتجه الحاويات والبضائع القادمة من الموانئ الآسيوية إلى موانئ الساحل الغربي لأمريكا الشمالية، ثم عبر الخطوط والسكك الحديدية والطرق البرية صوب الساحل الشرقي. وقبل التوسعات الجديدة في قناة بنما تصاعد الاعتماد على هذا الممر الأخير خاصة بالنسبة للسفن الضخمة التي لم تكن تستطيع عبور قناة بنما، ونظرًا إلى تكدس موانئ الساحل الغربي الأمريكي، فضلت العديد من سفن الحاويات التي يتعدى حجمها ما تسمح به قناة بنما والتي يطلق عليها Post Panamax استخدام ممر قناة السويس باعتباره الأكثر ملاءمة من حيث الوقت وتكلفة النقل.

ولكن مع التوسعات الجديدة في قناة بنما، من المتوقع أن تزداد قدرة قناة بنما على استقبال سفن الحاويات، وأن يتلاشي مصطلح Post Panamax الذي كان يعبر في مرحلة سابقة عن محدودية اتساع قناة بنما قبل مشروعات التطوير، ووفقًا لتوقعات إدارة قناة بنما فمن المأمول أن تسهم التوسعات الجديدة في زيادة نصيب قناة بنما من الحركة التجارية بين الساحل الشرقي للولايات المتحدة وشرق آسيا بحوالي 50%، في حين من المتوقع أن ينخفض نصيب الطريق الملاحي عبر الباسيفيكي والمرتبط بنظام النقل متعدد الوسائط من 75% إلى حوالي 60%. ولكن يظل تحقق هذا السيناريو مرهونًا بعدة شروط، من أهمها: استمرار تكدس مواني الساحل الأمريكي الغربي بما يشجع السفن الكبيرة على الاتجاه إلى قناة بنما، وقدرة مواني الساحل الشرقي على استقبال السفن الضخمة، وقدرة قناة بنما على تقديم رسوم تنافسية مقارنة بقناة السويس.

وعلى الرغم من تفوق قناة السويس على قناة بنما من حيث اختصار المدة الزمنية والمسافات في معظم الرحلات بين المواني الآسيوية وموانئ الساحل الشرقي الأمريكي، فإنه يوجد 3 خطوط رئيسية تتفوق فيها قناة بنما على قناة السويس، يتمثل أهمها في:

• خط نيويورك-هونج كونج: إذ توفر قناة بنما ما يوازي أكثر من نصف يوم وحوالي 331 ميل بحري بالمقارنة بقناة السويس.

• خط نيويورك- ملبورن: حيث يصل الفارق بين القناتين إلى ما يقرب من 5 أيام، وأكثر من 27 ألف ميل لصالح قناة بنما،

• خط نيويورك-شنغهاي: حيث يصل الفارق بين القناتين إلى 3 أيام لصالح قناة بنما، حيث تصل مدة العبور من خلال بنما إلى حوالي 25 يومًا، بينما تستغرق المسافة نفسها مرورًا بقناة السويس 28 يومًا، ما يمثل عبئًا إضافيًّا في الطاقة والوقت بزيادة تتراوح بين 4% و5%.

- مقارنة المسافات والزمن بين قناة السويس وقناة بنما

قضايا مائية

Gatun Lake is filled with rainwater, and the lake accumulates excess water during wet months. For the old locks, water is lost to the oceans at a rate of 101،000 m3 (26.7 million US gal; 81.9 acre⋅ft) per downward lock movement.[41] The ship's submerged volume is not relevant to this amount of water.

During the dry season, when there is less rainfall, there is also a shortage of water in Gatun Lake.[42]

As a signatory to the 2000 United Nations Global Compact and member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the ACP developed an environmentally and socially sustainable program for expansion, which protects the aquatic and terrestrial resources of the canal watershed. The expansion uses 3 water-saving basins at each new lock, diminish water loss and preserve freshwater resources along the waterway by reusing 60% of water from the basins into the locks in each transit.[43]

The mean sea level at the Pacific side is about 20 cm (8 in) higher than that of the Atlantic side due to differences in ocean conditions such as water density and weather.[44]

2015-16 was one of the driest periods on record, restricting ships passage;[45] 2019 was the fifth driest year for 70 years. Temperature rise has caused an increase in evaporation.[46] As of December 2023, ships were backing up because only 22 ships per day could transit due to low water levels, with the prediction that by February 2024 the number would be just 18.[47]

مشروعات مستقبلية

في ظل الطلب المتزايد على الشحن العالمي الفعال للبضائع، أصبحت القناة سمة بارزة من سمات الشحن العالمي في المستقبل المنظور. ومع ذلك، فالتغيرات في أنماط الشحن- خاصة زيادة أعداد السفن الأكبر من پنما-ماكس - ستتطلب إجراء تغييرات على القناة لتحتفظ بحصة سوقية كبيرة. في 2006، كان من المتوقع أن بحلول 2011، ستكون سفن الحاويات العالمية أكبر بنسبة 37% من سعة القناة الحالية، ومن ثم فالإخفاق في توسيع القناة من شأنه أن يؤدي إلى وقوع خسائر كبيرة في الحصة السوقية. القدرة القصوى المستدامة للقناة الحالية، في ظل بعض أعمال التحسينات ضيقة النطاق، تقدر ب330-50 مليون PC/UMS طن سنوياً؛ وكان من المتوقع أن تصل إلى هذه القدرة فيما بين 2009 و2012. ما يقارب من 50% من سفن الشحن كانت بالفعل تستخدم العرض الكامل للأهوسة.[48]

مشروع التوسيع على غرار مشروع الهويس الثالث عام 1939، يسيمح بمرور عدد أكبر من السفن ويزيد من القدرة على التعامل مع السفن الأكبر، والذي كان تحت الدراسة لبعض الوقت،[49] وتم الموافقة عليه من قبل حكومة پنما،[50] وهو قيد التنفيذ، وكان من المتوقع اكتماله في نهاية 2014.[51] تبلغ تكلفة المشروع 5.25 بليون دولار، وسيضاعف المشروع من قدرة القناة، مما يسمح بمرور المزيد من السفن وعبور سفن أطول وأعرض. مقترح توسيع القناة هذا تم الموافقة عليه في استفتاء وطني عقد في 22 أكتوبر 2006، وحاز على موافقة تقارب 80%.[52]

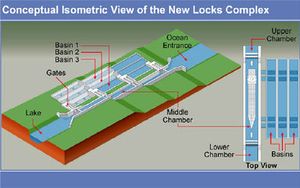

مشروع الطاقم الثالث من الأهوسة

تهدف الخطة الحالية إلى إنشاء two new flights من الأهوسة تُبنى بشكل موازي، ويتم تشغيلها بالإضافة الأهوسة القديمة: واحد على شرق أهوسة گاتون الحالية، والآخر جنوب غرب أهوسة ميرافلورز، يدعم كل منها بواسطة قنوات توصيل. سيرتفع كل flight من مستوى سطح البحر مباشرة إلى مستوى سطح بحيرة گاتون؛ the existing two-stage ascent عند أهوسة ميرافلورز وپدرو ميگويل لن يتم be replicated. خاصية البوابات المنزلقة، سيتم مضاعفتها للأمان، وستكون بطول 427 متر، وعرض 55 متر، وعمق 18.3 متر. سيسمح هذا بعبور سفن ذات عارضة أكبر عن 49 متر، وغاطس يزيد عن 15 متر، أي ما يعادل سفينة حاويات تحمل ما يقارب 12.000 حاوية، كل منها بطول 6.1 متر (TEU).

ستدعم الأهوسة الجديدة بقنوات توصيل، تشمل قناة بطول 6.2 كم عند ميرافلورز تصل الأهوسة بگيلارد كت، على حافة بحيرة ميرافلروز. سيصل كل قناة إلى 218 متر، مما يتطلب بالنسبة لسفن ما بعد پنما-ماكس، أن تبحر سفينة في إتجاه واحد في كل مرة. سيتم توسعة گيلارد كت والقناة عبر بحيرة گاتون 280 متر على الأقل في قطاعات مستقيمة و366 متر على الأقل على الضفتين. سيرتفع المنسوب الأقصى لبحيرة گاتون من 26.7 متر إلى 27.1 متر.

سيرافق كل flight من الأهوسة تسعة أحواض إعادة استخدام مياه (ثلاثة لكل حجرة هويس)، سيبلغ غرض كل حوض ما يقارب 70 متر، وطوله 430 متر وعمقه 5.50 متر. هذه الأحواض التي تغذيها الجاذبية، ستسمح بإعادة استخدام 60% من المياه المستخدمة في كل عبور؛ وبالتالي ستستخدم الأهوسة الجديدة 7% أقل من المياه لكل عبور عن حارات الأهوسة القائمة. تعميق بحيرة گاتون ورفع مستوى المياه الأقصى لها سيوفر أيضاً سعة تخزينية أكبر بكثير. تهدف هذه التدابير إلى السماح بتوسيع القناة للتشغيلها بدون إنشاء خزانات جديدة.

تقدر تكلفة المشروع ب5.25 بليون دولار. المشروع مصمم للسماح بنمو متوقع للمرور يتراوح بين 280 مليون طن في 2005 إلى 510 مليون طن في 2025. ستصل القدرة القصوى المستدامة للقناة بعد توسيعها إلى ما يقارب 600 مليون طن سنوياً. سيستمر حساب الرسوم حسب حمولة السفينة، وليس على استخدام الأهوسة.

من المتوقع أن يتم افتتاح الأهوسة الجديدة للمرور في 2016. الأهوسة الحالية والتي سيكون عمرها في ذلك الوقت 100 عام، ستتيح للمهندسين مدخل أكبر للصيانة، ويتوقع أن تستمر في العمل لأجل غير مسمى.[48] في فبراير 2007 نُشرت مقالة في مجلة پوپيولار مكانكس ووصفت خطط القناة، وركزت على الجوانب الهندسية لمشروع التوسيع.[53] وهناك أيضاً مقالة متممة نشرت في عدد فبراير 2010 من پوپيولار ميكانيكس.[54]

في 3 سبتمبر 2007، وقف آلاف الپنميين عبر تلة پارايسو في پنما لمشاهدة التفجير الأول الهائل وإطلاق برنامج التوسيع. ستتضمن المرحلة الأولى من المشروع تجفيف خندق حفريات بعرض 218 يصل گايلارد كت بساحل المحيط الهادي، وإزالة 47 مليون متر مكعب من الأرض والصخر.[55] بحلول يونيو 2012، تم الإنتهاء من رص 30 م من الخرسانة المسلحة، أول 46 صف منها يحاذي الجدار الصخري الجديد على ساحل الهادي.[56] بحلول أوائل يوليو 2012، أعلن أن مشروع توسيع القناة سيتأخر ستة أشهر عن الجدول الزمني، مما أدى لتوقع إفتتاح المشروع في أبريل 2015 بدلاً من أكتوبر 2014، كما كان مخطط في الأصل.[57] بحلول سبتمبر 2014، كان من المتوقع أن تُفتتح البوابات الجديدة للعبور في أوائل 2016.[58][59][60][61]

في يوليو 2009 أُعلن أن شركة التجريف البلجيكية يان دي نول، بالاشتراك مع كومنسورتيوم يضم شركة ساكير ڤالهرموسو الإسپانية، إمپرگيلو الإيطالية وگروپو كوسا الپنمية، فازوا بعقد لبناء ستة أهوسة جديدة. بلغت قيمة العقد 100 مليون دولار ويشمل قيام الشركة البلجيكية بأعمال التجريف للسنوات القليلة القادمة وصفقة ضخمة من الأعمال لأجل قسم الانشاءات بالشركة. تصميم الأهوسة هو نسخة طبق الأصل من هويس برندرخت، والذ يبلغ عرضه 68 متر وطوله 500 متر، مما يجعله أكبر هويس بالعالم. اكتمل الهويس عام 1989 ويقع داخل ميناء أنتورپ، والذي ساعدت في بناؤه شركة دي نول البلجيكية، ولا يزال مهندسي ومتخصصي الشركة جزءاً من المشروع.[62]

في يناير 2014، هدد خلاف حول العقد بعرقة تقدم المشروع.[63] [64] كان هناك تأخير أقل من شهرين، إلا أن عمل أعضاء الكونسورتيوم حقق أهدافه بحلول يونيو 2014.[65] [66]

وصلة سكك حديد كولومبيا المنافسة

قناة نيكاراگوا المنافسة

مقالة مفصلة: قناة نيكاراگوا

مقالة مفصلة: قناة نيكاراگوا

وافق البرلمان النيكاراگوي على خطط تكليف شركة صينية بشق قناة بطول 173 ميل عبر نيكاراگوا. تبعاً للاتفاقية، ستكون الشركة مسئولة أيضاً عن تشغيل وصيانة القناة لمدة 50 سنة. بدأت أعمال الانشاء في هذا المشروع في ديسمبر 2014. تأمل حكومة نيكاراگوا أن يعمل هذا المشروع على إنعاش الاقتصاد، لكن لدى المعارضة مخاوف عميقة حول آثاره البيئية الهائلة. عند اكتمال المشروع في أوائل 2019، سيتم تشريد مئات الآلاف من السكان المحليين المقيمين حول القناة وتدمير ما يقارب من مليون فدان من النظم البيئية الحساسة.[67][68]

في 7 يوليو 2014، صرح رئيس شركة إتش كيه نيكاراگوا للتنمية الاستثمارية (مجموعة HKND)، أثناء مناقشة مجموعة طلبة جامعة الهندسة الوطنية في ماناگوا، بأن مسار قناة نيكاراگوا المقترحة تم الموافقة عليه. بدأت أعمال الانشاءات في ديسمبر 2014 ومن تتوقع HKND أن تستغرق خمس سنوات.[69]

مشاريع أخرى

قام الأفراد، الشركات، والحكومات بالبحث في إمكانية إنشاء موانئ مياه عميقة ووصلات سكك حديدية للتوصيل بين السواحل "كقناة جافة" في گواتيمالا، كوستاريكا، والسلڤادور/هندوراس. ومع ذلك، فخطط إنشاء وصلات بحرية-سكك حديدية-بحرية هذه لم تتحقق بعد.[70]

مرشدو القناة

بحيرة گاتون

انظر أيضاً

- سياسة منظمة القناة

- مشروع توسيع قناة پنما

- Cost overrun

- Isthmus of Tehuantepec Tehuantepec Route

- قائمة الممرات المائية

- قناة نيكاراگوا

- مضيق ماجلان

المصادر

- ^ "Panama Canal Traffic—Years 1914–2010". Panama Canal Authority. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ^ "Seven Wonders". American Society of Civil Engineers. Archived from the original on 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ أ ب "Hydroelectric Plants in Panama". 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2016-06-26.

- ^ أ ب "Panama Canal Traffic—Fiscal Years 2002–2004" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-12-01. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ "Historical Map & Chart Project". NOAA. Archived from the original on 2007-09-05. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ "Annual Report 2017" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-03. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ "Infosheet No. 30: Modern ship size definitions" (PDF). Lloyd's Register. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-24.

- ^ "Professional Resources in Science and Mathematics (PRISM)" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ "The Panama Canal". Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Pride, Alfred M. (1986). "Pilots, Man Your Planes". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute. Supplement (April): 28–35.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAP 2016 - ^ "New Panamax publication by ACP" (PDF). November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 6, 2009. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ "Marine Tariff". Panama Canal Authority. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ Panama Canal Toll Table http://www.pancanal.com/eng/op/tariff/1010-0000-Rev20160414.pdf[dead link]

- ^ "Maritime Services - PanCanal.com". www.pancanal.com. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ^ "Toll Tariffs Approved By Cabinet Council And Published On The Official Gazzette. Implementation: October 1, 2017 (Fy 2018)" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "The Panama Canal - All You Need to Know". Panama Passion (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2020-07-11. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ "US Today Travel: Panama Canal Facts". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- ^ "ACP rectifica récord en pago de peaje" (in الإسبانية). La Prensa. 2008-06-24. Archived from the original on August 16, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ "Récord en pago de peajes y reserva". La Prensa. Ediciones.prensa.com. 2007-04-24. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ^ "Cupo de subasta del Canal alcanza récord. La Prensa. Sección Economía & Negocios. Edición 25 August 2006 in Spanish". Mensual.prensa.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ^ "About ACP - PanCanal.com". Panama Canal Authority. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ Cullen, Bob (March 2004). "Panama Rises". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ^ "ACP 2005 Annual Report" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ "News—PanCanal.com; Panama Canal Authority Announces Fiscal Year 2008 Metrics". Panama Canal Authority. 2008-10-24. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ "News—PanCanal.com; Panama Canal Authority Announces Fiscal Year 2009 Metrics". Panama Canal Authority. 2009-10-30. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ Lipton, Eric (2004-11-22). "New York Port Hums Again, With Asian Trade". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2005-03-07.

- ^ أ ب "ACP 2009 Annual Report" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ^ "Panama Canal Traffic—Fiscal Years 2013 through 2015" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-19.

- ^ Nettleton, Steve (2000). "Transfer heavy on symbolism, light on change". CNN Interactive. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008.

- ^ "9 Facts about the Panama Canal Expansion – Infographic". Mercatrade. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ "Panama Canal reopens after temporary closure". BBC News. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ "The Press Association: Panama flooding displaces thousands". 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ "NOTICIAS PANAMÁ—PERIÓDICO LA ESTRELLA ONLINE: Gobierno abrirá parcialmente Puente Centenario; Corredores serán gratis [Al Minuto]". 2010-12-13. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ "Rain Causes Panama Canal Bridge To Collapse". digtriad.com. 2010-12-12. Archived from the original on 2013-05-01. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ "Entrance to Panama Canal Bridge Closed due to Rain Damage". 2010-12-13. Archived from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ "Aftermath of Panama flooding hits transport and finances—rain continues". 2010-12-13. Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ Mack, Gerstle (1944). The Land Divided—A History of the Panama Canal and other Isthmian Canal Projects. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2006.

- ^ "Proposal for the Expansion of the Panama Canal" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 24 April 2006. p. 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21.

- ^ "Panama Canal expansion will allow transit of larger ships with greater volumes". Today in Energy. EIA. September 17, 2014. Archived from the original on April 25, 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- ^ "Physical characteristics of the waterway". Panama Canal Authority. 2001. Archived from the original on 2001-10-14. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

How much water is required to fill a lock chamber? Each lock chamber requires 101,000 cubic meters of water. An average of 52 million gallons of fresh water are used.

- ^ Fountain, Henry (2019-05-17). "What Panama's Worst Drought Means for Its Canal's Future". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 2, 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ Alarcón, Luis F.; Ashley, David B.; Sucre de Hanily, Angelique; Molenaar, Keith R.; Ungo, Ricardo (October 2011). "Risk Planning and Management for the Panama Canal Expansion Program". Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 137 (10): 762–771. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000317.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". psmsl.org. Retrieved 2023-05-01.

- ^ Sheridan, Mary Beth (2023-08-24). "Traffic jam at Panama Canal as water level plummets". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ^ Jocelyn Timperley (2020-01-15). "The Panama Canal is running out of water". Wired UK (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ^ Yerushalmy, Jonathan (22 December 2023). "Changing climate casts a shadow over the future of the Panama Canal – and global trade". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Relevant Information on the Third Set of Locks Project" (PDF). Panama Canal Authority. 2006-04-24. Retrieved 2006-04-25.

- ^ "The Panama Canal". Business in Panama. Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- ^ Monahan, Jane (2006-04-04). "Panama Canal set for $7.5bn revamp". BBC News.

- ^ "Panama Canal Authority: Panama Canal Expansion is "2009 Project Finance Deal of the Year", 12 March 2010". Pancanal.com. 2010-03-12. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

- ^ "Panama approves $5.25 billion canal expansion". MSNBC.com. 2006-10-22.

- ^ Reagan, Brad (February 2007). "The Panama Canal's Ultimate Upgrade". Popular Mechanics.

- ^ Kaufman, Andrew (February 2010). "The Panama Canal Gets a New Lane". Popular Mechanics.

- ^ "Work starts on biggest-ever Panama Canal overhaul". Reuters. 2007-09-04.

- ^ Panama Canal Authority (19 June 2012). "Panama Canal Completes First Monolith at the New Pacific Locks". Retrieved 2012-06-20.

- ^ Ship and Bunker (2 July 2012). "Delay Confirmed on Panama Canal Expansion Project". Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ Dredging News Online (29 August 2014). "Panama Canal Authority updates Maersk Line on expansion programme". Dredging News Online. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Dredging News Online (1 September 2014). "Panama Canal Authority updates Maersk Line on expansion programme". Hellenic Shipping News. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- ^ Panama Canal Authority (20 August 2014). "Panama Canal Updates Maersk Line on Expansion Program". Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ^ Smith, Bruce (9 Sep 2014). "Maritime panel to hold sessions on port congestion". Charlotte Observer. Retrieved 11 Sep 2014.

- ^ "De Nul dredging company to build locks in Panama Canal". Flanders Today. 2009-07-17.

- ^ "Contract dispute jeopardizes Panama Canal schedule". American Shipper. January 2, 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Lomi Kriel; Elida Moreno (January 8, 2014). "Panama Canal refuses to pay $1 billion more for expansion work". Reuters. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Panama Canal Authority (20 February 2014). "Panama Canal New Locks Project Works Resume". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ^ Panama Canal Authority (10 June 2014). "Second Shipment of new gates arrive at the Panama Canal". Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ^ "A Chinese company wants to build a new canal in America (news in Estonian)". Postimees. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Nicaragua launches construction of inter-oceanic canal". BBC. December 23, 2014. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ Van Marle, Gavin (July 2013). "Canal mania hits central America with three more Atlantic-Pacific projects". The Load Star.

للاستزادة

- Hoffman, Jon T.; Brodhead, Micheal J; Byerly, Carol R.; Williams, Glenn F. (2009). The Panama Canal: An Army's Enterprise. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. 70–115–1.

- Jaen, Omar. (2005). Las Negociaciones de los Tratados Torrijos-Carter, 1970-1979 (Tomos 1 y 2). Panama: Autoridad del Canal de Panama. ISBN 9962-607-32-9 (Obra completa)

- Jorden, William J. (1984). Panama Odyssey. 746 pages, illustrated. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292764-69-3

- McCullough, David. (1977). The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-22563-4

- Maurer, Noel, and Carlos Yu. The Big Ditch: How America Took, Ran, and

Ultimately Gave Away the Panama Canal (Princeton University Press, 2010); 420 pp. ISBN: 978-0-691-14738-3. Econometric analysis of costs ($9 billion in 2009 dollars) and benefits to US and Panama

- Mellander, Gustavo A.(1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Daville,Ill.:Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1563281554. OCLC 42970390.

- Murillo, Luis E. (1995). The Noriega Mess: The Drugs, the Canal, and Why America Invaded. 1096 pages, illustrated. Berkeley: Video Books. ISBN 0-923444-02-5.

- Parker, Matthew. (2007). Panama Fever: The Epic Story of One of the Greatest Human Achievements of All Time - The Building of the Panama Canal. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51534-4

- Sherman, Gary. "Conquering the Landscape (Gary Sherman explores the life of the great American trailblazer, John Frank Stevens)," History Magazine, July 2008.

- Cullen, Ben. (2010). The Panama Canal and Me: A Panamax Special. ISBN 9780821277546

- Mills, J. Saxon. (1913). The Panama Canal -- A history and description of the enterprise A Project Gutenberg free ebook.

وصلات خارجية

- Panama Canal Authority website - Has a simulation showing how the canal works

- Making the Dirt Fly, Building the Panama Canal Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- Canalmuseum — History, Documents, Photographs and Stories

- History of the Canal Zone from CZ Brats

- Judicial Watch, Inc. v. Panama Canal Commission case - archived

- Freshwater and Marine Image Bank – Panama Canal University of Washington Libraries - ongoing digital collection of images

- Early stereographic images of the construction University of California

- A.B. Nichols Panama Canal Collection at the Linda Hall Library Archival collection of maps, blueprints, photographs, letters, and other documents, collected by Aurin B. Nichols, an engineer who worked on the canal project through from 1899 until its completion.

- 2700 digitised National Archives public domain images Photos of the building and early days of the Panama Canal digitised by GoZonian.org from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Originally from 8 x 10 glass plates

- Gatun Lake Benefits

- Panama & the Canal Digital Collection

- New Plans For Panama, by Stephen L. Freeman 1947 article about possible post World War II plans for the Panama Canal including first mention of a sea level canal to replace the locks

- Footage of ships going through Panama Canal in 1917

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles with dead external links from January 2018

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using start date and age with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox canal with unknown parameters

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with hAudio microformats

- قوائم إحداثيات

- Geographic coordinate lists

- Articles with Geo

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ أبريل 2016

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2016

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- عمارة 1914

- معالم هندسة مدنية تاريخية

- هندسة عملاقة

- قناة پنما

- قنوات في پنما