قائمة مواقع التراث العالمي في إيران

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972.[2] Iran accepted the convention on 26 February 1975, making its historical sites eligible for inclusion on the list. As of 2023, twenty-seven sites in Iran are included.[1]

The first three sites in Iran, Meidan Naghshe Jahan, Isfahan, Persepolis and Tchogha Zanbil, were inscribed on the list at the 3rd Session of the World Heritage Committee, held in Cairo and Luxor, Egypt in 1979.[3] They remained the Islamic Republic's only listed properties until 2003, when Takht-e Soleyman was added to the list.[4] The latest addition was the Hyrcanian forests, inscribed in 2019.

In addition to its inscribed sites, Iran also lists more than 50 properties on its tentative list.[5]

مواقع التراث العالمي

- Site; named after the World Heritage Committee's official designation[6]

- Location; at city, regional, or provincial level and geocoordinates

- Criteria; as defined by the World Heritage Committee[7]

- Area; in hectares and acres. If available, the size of the buffer zone has been noted as well. A lack of value implies that no data has been published by UNESCO

- Year; during which the site was inscribed to the World Heritage List

- Description; brief information about the site, including reasons for qualifying as an endangered site, if applicable

| Site | Image | Location | Criteria | Area | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran | West Azerbaijan Province38°58′44″N 45°28′24″E / 38.97889°N 45.47333°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(vi) |

129 (320) | 2008 | In Iran’s northwest, the Armenian Monastic Ensembles, including St Thaddeus, St Stepanos, and the Chapel of Dzordzor, reflect Armenian Christian architectural brilliance since the 7th century. These monasteries showcase a fusion of Armenian, Byzantine, Orthodox, and Persian cultural exchanges. Located at the southeastern edge of the Armenian cultural sphere, they have played a pivotal role in propagating Armenian culture. Today, they are the region’s well-preserved cultural vestiges and active pilgrimage sites, preserving Armenian religious heritage over many centuries.[8] | |

| Bam and its Cultural Landscape |

|

Kerman Province29°07′00″N 58°22′00″E / 29.11667°N 58.36667°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(iv)(v) |

— | 2004 | Bam, positioned in a desert on the southern edge of the Iranian plateau, dates back to the Achaemenid era (6th-4th centuries BC). Thriving between the 7th and 11th centuries at the intersection of significant trade routes, Bam was renowned for its silk and cotton. The city’s survival depended on qanāts, ancient underground irrigation systems, with Bam showing some of Iran’s earliest examples. The Arg-e Bam stands out as a well-preserved fortified medieval town, constructed with traditional mud layer techniques (Chineh).[9] |

| Bisotun |

|

Kermanshah Province34°23′18″N 47°26′12″E / 34.38833°N 47.43667°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii) |

187 (460) | 2006 | Bisotun, located on an ancient trade route in Iran, holds artifacts from various historic periods, including the Median and Achaemenid empires. The site’s highlight is a bas-relief and cuneiform of Darius I from 521 BC, depicting his rise to power and sovereignty. This scene is accompanied by inscriptions in three languages narrating Darius’s conquests and the reassertion of the Persian Empire, representing a mingling of artistic and literary traditions. Beyond the Achaemenid era, the location also contains relics from previous and subsequent times, tracing a long lineage of cultural heritage.[10] |

| Cultural Landscape of Maymand |

|

Kerman Province30°10′05″N 55°22′32″E / 30.16806°N 55.37556°E | Cultural:

(v) |

4,954 (12,240) | 2015 | Maymand, situated in a semi-arid valley of southern Iran, is known for its self-sustaining, semi-nomadic agro-pastoralist community. Residents practice seasonal migration, utilizing mountain pastures and temporary settlements during spring and autumn, while residing in unique cave dwellings during winter. This cultural landscape showcases an ancient system of human transhumance, which is rare in arid environments and reflects a tradition possibly more common in historical times.[11] |

| Cultural Landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat |

|

Kurdistan Province | Cultural:

(iii)(v) |

106 (260) | 2021 | The Hawraman/Uramanat region of Iran, home to the Kurdish Hawrami people since 3000 BCE, encompasses a rugged landscape within the Zagros Mountains. It includes two main valleys with distinctive tiered architecture and agropastoral practices suited to the steep terrain. The persistent presence of the Hawrami is marked by archaeological sites and the dynamic adaptation of their semi-nomadic lifestyle, moving between elevations seasonally. The region’s twelve villages highlight the innovative responses of the Hawrami to the challenges of mountain living, amidst a backdrop of rich biodiversity.[12] |

| Gonbad-e Qābus |

|

Golestan Province37°15′29″N 55°10′08″E / 37.25806°N 55.16889°E | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

1 (2.5) | 2012 | The tomb of Qābus Ibn Voshmgir, from AD 1006, in northeast Iran, stands as a cultural link between Central Asian nomads and Iranian civilization. This 53-meter-high tower, highlighting Islamic architectural ingenuity, is all that remains of Jorjan, an ancient hub of knowledge lost to Mongol invasions. Its innovative brick design with geometric precision reflects the mathematical and scientific prowess of the Muslim world as of the first millennium AD.[13] |

| Golestan Palace |

|

Tehran35°40′47″N 51°25′13″E / 35.67972°N 51.42028°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

5.3 (13) | 2013 | The Golestan Palace, a stunning architectural gem from the Qajar era, exemplifies the fusion of traditional Persian art and craft with Western influences. As one of Tehran’s oldest building complexes, it became the Qajar dynasty’s center of power after they took the throne in 1779 and declared Tehran the national capital. Encircling a garden with pools and green spaces, the Palace’s distinctive decorations and architectural elements are largely from the 19th century. The Golestan Palace marks the emergence of a novel style that blends classic Persian elements with the architectural methods and technologies of the 18th century.[14] |

| Lut Desert |

|

Kerman and Sistan and Baluchestan Provinces | Natural:

(vii)(viii) |

2,278,012 (5,629,090) | 2016 | The Lut Desert, also known as Dasht-e-Lut, situated in southeast Iran, is one of the most extreme and dry subtropical areas on Earth, particularly between June and October, when powerful winds cause staggering aeolian erosion. This desert showcases some of the world’s most striking yardangs large wind-sculpted ridges as well as an expanse of rocky plateaus and vast fields of dunes. As a natural property, it stands as a prime example of geological forces continuously shaping the Earth’s surface.[15] |

| Sassanid Archaeological Landscape in Fars Province (Bishabpur, Firouzabad, Sarvestan) |

|

Fars Province | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(v) |

639.3 (1,580) | 2018 | In the southeast of Fars Province, Iran, eight archaeological sites are clustered across three zones: Firuzabad, Bishapur, and Sarvestan. These areas exhibit an array of well-preserved urban designs, fortified buildings, and palaces that trace back to both the dawn and decline of the Sassanian Empire, which lasted from 224 to 658 CE. Among these remarkable sites are those founded by Ardashir Papakan, the empire’s initiator, including his capital and various constructions by his heir, Shapur I. These sites are a testament to the adept integration of the empire’s architecture with the existing landscape and showcase the enduring legacies of Achaemenid and Parthian traditions, as well as the significant influence of Roman art, which went on to profoundly shape the architectural designs of the subsequent Islamic era.[16] |

| Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan |

|

Isfahan, Isfahan Province | Cultural:

(ii) |

2.0756 (5.129) | 2012 | The Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan, an iconic Friday mosque dating back to 841 AD, is a prominent architectural lineage showcase, reflecting twelve centuries of mosque construction in Iran. Being the nation’s most ancient mosque still standing, it serves as an archetype for mosque architecture spreading across Central Asia. The expansive, over 20,000 square meter complex notably first incorporated the Sassanid four-courtyard scheme into Islamic sacred structures. The mosque’s innovative double-shelled ribbed domes have significantly influenced regional architecture. Additionally, this historic edifice boasts an array of ornate details that chart the evolution of Islamic art for over a millennium.[17] |

| Naqsh-e Jahan Square |

|

Isfahan, Isfahan Province | Cultural:

(i)(v)(vi) |

— | 1979 | Established in the 17th century by Shah Abbas I, this site marvelously encapsulates Safavid Persian architecture and urbanism, surrounded by an integrated complex of stately buildings and two-level arcades. Notable structures include the Royal Mosque with its intricate Islamic motifs and the Mosque of Sheykh Lotfollah known for its ornate decoration. The Qaysariyyeh Portico heralds the entrance to the main bazaar, highlighting the site’s economic significance. Additionally, the Timurid palace within the complex sheds light on architectural traditions before the Safavid era. Collectively, these edifices chronicle the zenith of the social and cultural landscape in Safavid Persia.[18] |

| Pasargadae |

|

Fars Province30°11′38″N 53°10′02″E / 30.19389°N 53.16722°E | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

160 (400) | 2004 | Pasargadae holds the distinction of being the inaugural dynastic capital of the expansive Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus II the Great in Pars, the core region from which the Persians originated, during the 6th century BC. It stands as a monumental testament to the early period of royal Achaemenid art and architecture and offers profound insight into Persian civilization. Among the 160-hectare archaeological site’s most significant and preserved features are the Mausoleum of Cyrus II, an archetype of ancient Persian construction, and the Tall-e Takht, which is a fortified platform likely used for royal ceremonies. Additionally, the site houses an imperial ensemble that includes a gatehouse, an audience hall for receiving delegations, a residential palace, and landscaped gardens, elements that confirm the sophistication and grandeur of early Achaemenid design. Pasargadae was the epicenter of the first vast and culturally diverse empire in Western Asia, stretching from the Eastern Mediterranean and Egypt all the way to the Hindu River. Its significance also lies in the respect and incorporation of the myriad cultures within its borders, which is eloquently expressed in its architecture—a fusion that mirrors the diversity of its constituent peoples. This ideology of cultural respect and integration marks Pasargadae as not just a historical site, but as a symbol of ancient tolerance and multiculturalism.[19] |

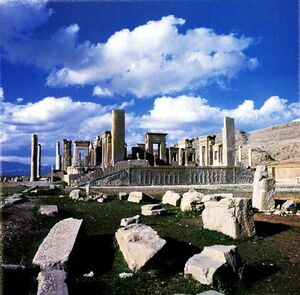

| Persepolis |

|

Fars Province29°56′04″N 52°53′25″E / 29.93444°N 52.89028°E | Cultural:

(i)(iii)(vi) |

12.5 (31) | 1979 | Persepolis, the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, was conceived by Darius I in 518 B.C. This majestic city was constructed atop a grand terrace that blends human ingenuity with natural topography. The terrace served as the foundation for an elaborate palace complex, where the “king of kings” erected grandiose structures influenced by Mesopotamian design. The site’s monumental ruins which have withstood the passages of time highlight both the empire’s grandeur and the remarkable craftsmanship of its builders. These imposing edifices and detailed reliefs are emblematic of the architectural and cultural might of the Achaemenid Empire, making Persepolis an unparalleled archaeological treasure that continues to intrigue scholars and tourists alike.[20] |

| Shahr-e Sukhteh |

|

Sistan and Baluchestan Province30°35′38″N 61°19′40″E / 30.59389°N 61.32778°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

275 (680) | 2014 | Shahr-i Sokhta, aptly named ‘Burnt City’, stands at the crossroads of ancient Bronze Age trade routes on the Iranian plateau, bearing witness to the dawn of complex societies in eastern Iran. Established circa 3200 BC, it was inhabited over four principal periods extending to 1800 BC. Within its confines, the city evolved to host an array of specialized zones including monumental structures, residential neighborhoods, burial sites, and industrial areas. The migration of water resources and shifts in climate precipitated the city’s decline, leading to its desertion in the early second millennium BC. Today, the remaining mudbrick architecture, the extensive necropolis, and the surplus of significant artefacts that have been discovered offer a deep well of knowledge. The arid desert air has preserved these finds in an exceptional state, providing a treasure trove of data about early societal structures as well as the intercommunicating civilizations of the third millennium BC.[21] |

| Sheikh Safi al-din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in Ardabil |

|

Ardabil Province38°14′55″N 48°17′29″E / 38.24861°N 48.29139°E | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(iv) |

2 (4.9) | 2010 | This spiritual retreat, established between the early 16th and late 18th centuries, embodies the Sufi tradition and showcases the utilization of traditional Iranian architecture to optimize space for a multi-functional complex. The retreat includes a diverse range of components such as a library, mosque, school, mausolea, cistern, hospital, kitchens, bakery, and administrative offices. Significantly, the path leading to the shrine of the Sheikh is segmented into seven parts, reflecting the seven stages of Sufi spiritual journey, and is punctuated by eight gates representing the eight Sufi attitudes. The entire complex boasts well-maintained facades and interiors that are ornately decorated, housing a remarkable collection of historic artefacts. As a whole, the site offers a unique and intact glimpse into the elements of medieval Islamic architecture, specifically tailored to the spiritual and practical needs of a Sufi sanctuary. The harmonious integration of various facilities within the retreat illustrates the Sufi principle of unity and serves as a physical manifestation of the Sufi spiritual path within architectural forms.[22] |

| Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System |

|

Khuzestan Province32°01′07″N 48°50′09″E / 32.01861°N 48.83583°E | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(v) |

240 (590) | 2009 | Shushtar’s Historical Hydraulic System is a universally-acclaimed masterpiece of ingenuity, with origins stretching back to the reign of Darius the Great in the 5th century B.C. This complex infrastructure comprises the creation of diversion canals from the Kârun River, notably the Gargar canal, which persists to this day, delivering water to Shushtar through a network of tunnels that energize watermills. These ancient waterworks create a dramatic cascade over cliffs, flowing into a collecting basin and then onto the southward plain, enriching the land to sustain orchards and farming across approximately 40,000 hectares, an area also referred to as Mianâb or “Paradise”. The system encompasses a series of archaeological wonders, like the Salâsel Castel, which served as the control center for the hydraulics, a tower for monitoring water levels, various dams, bridges, basins, and mills. The Historical Hydraulic System is a testament to the advanced engineering skills of the Elamites, the Mesopotamians, Nabatean hydraulic expertise, and the architectural influences from the Roman era, signifying a confluence of different cultures in the evolution of one of the most sophisticated water management systems of the ancient world.[23] |

| Soltaniyeh |

|

Zanjan Province36°26′07″N 48°47′48″E / 36.43528°N 48.79667°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

790 (2,000) | 2005 | The mausoleum of Oljaytu, erected from 1302 to 1312 in Soltaniyeh, the then capital of the Ilkhanid dynasty established by the Mongols, stands in the Zanjan province of Iran. Renowned for epitomizing the epitome of Persian architecture and significantly contributing to the evolution of Islamic architecture, the structure’s octagonal design is topped by a striking 50-meter-high dome adorned with turquoise-blue faience and encircled by eight svelte minarets. It represents the earliest known example of a double-shelled dome in Iran. The interior decorations of the mausoleum are exceptional, leading experts like A.U. Pope to see it as a precursor to the architectural magnificence of the Taj Mahal.[24] |

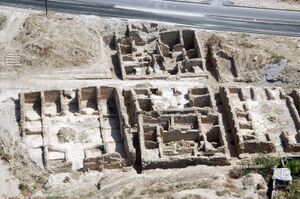

| Susa |

|

Khuzestan Province32°11′22″N 48°15′22″E / 32.18944°N 48.25611°E | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

350 (860) | 2015 | In the southwest of Iran, within the lower Zagros Mountains, lies a site featuring a cluster of archaeological mounds alongside the Shavur River, and across the river is Ardeshir’s palace. Susa, the area in question, reveals a chronological stack of urban settlements stretching back from the late 5th millennium BCE to the 13th century CE. This site stands out as a bearer of witness to the now mostly vanished cultural traditions of the Elamites, Persians, and Parthians, exhibiting a diverse range of administrative, residential, and palatial ruins that testify to these civilizations’ complex histories.[25] |

| Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex |

|

East Azerbaijan Province38°04′53″N 46°17′35″E / 38.08139°N 46.29306°E | Cultural:

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

29 (72) | 2010 | The historic bazaar complex of Tabriz, a hub of cultural exchange since ancient times, stands as a prime commercial center from the times of the Silk Road. Comprising interconnected, covered brick structures for various uses, the bazaar flourished as early as the 13th century. At that time, Tabriz, located in Eastern Azerbaijan province, rose to prominence as the capital of the Safavid empire. Though it lost its capital status in the 16th century, Tabriz retained its significance as a mercantile nexus until the late 18th century, despite Ottoman expansion. Today, the bazaar is one of the most comprehensive living examples of Iran’s traditional market and cultural milieu.[26] |

| Takht-e Soleyman |

|

West Azerbaijan Province36°36′14″N 47°14′06″E / 36.60389°N 47.23500°E | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(vi) |

10 (25) | 2003 | The Takht-e Soleyman archaeological site in northwest Iran is located in a valley amidst a volcanic mountain region. This significant historical site features a principal Zoroastrian sanctuary reconstructed during the Ilkhanid (Mongol) period in the 13th century, alongside a Sasanian era (6th and 7th centuries) temple dedicated to the deity Anahita. This site is not only a testament to ancient spirituality but also has had a profound impact on the evolution of Islamic architectural design through the layout and structures of the fire temple and palace.[27] |

| Tchogha Zanbil |

|

Khuzestan Province32°05′00″N 48°32′00″E / 32.08333°N 48.53333°E | Cultural:

(iii)(iv) |

— | 1979 | Tchogha Zanbil, the sacred city of the ancient Elamite Kingdom, is enveloped by three massive concentric walls. Established around 1250 B.C., it was never completed due to an invasion by Ashurbanipal, demonstrated by many abandoned bricks at the site.[28] |

| The Persian Garden |

|

Many Provinces (Fars, Kerman, Razavi Khorasan, Yazd, Mazandaran, and Isfahan Provinces) | Cultural:

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(vi) |

716 (1,770) | 2011 | The property encompasses nine gardens across various provinces, showcasing the diversity of Persian garden designs rooted in principles dating back to the 6th century BC during the time of Cyrus the Great. Consistently divided into four sectors, these gardens use water for irrigation and ornamentation, symbolizing Eden and the Zoroastrian elements of sky, earth, water, and plants. Dating back to different periods, these gardens include buildings, pavilions, walls, and advanced irrigation systems. Their influence extends to the art of garden design in regions as distant as India and Spain.[29] |

| Trans-Iranian Railway |

|

Mazandaran, Tehran and Khuzestan Provinces | Cultural:

(ii)(vi) |

5,784 (14,290) | 2021 | The Trans-Iranian Railway, spanning 1,394 kilometers, links the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf, traversing diverse terrains, including mountains, rivers, highlands, forests, and plains, across four climatic zones. Built from 1927 to 1938 through collaboration between the Iranian government and 43 international contractors, the railway stands out for its engineering feats. Overcoming steep routes, it involved extensive mountain cutting, the construction of 174 large bridges, 186 small bridges, and 224 tunnels, including 11 spiral tunnels. Notably, the project was funded through national taxes to maintain independence from foreign investment and control.[30] |

| Persian Qanat |

|

Razavi Khorasan, South Khorasan, Yazd, Kerman, Markazi and Isfahan Provinces | Cultural:

(iii)(iv) |

— | 2016 | Iran's arid regions rely on the ancient qanat system, tapping alluvial aquifers at valley heads and directing water through gravity-fed underground tunnels for agricultural and settlement support. Eleven representative qanats, featuring rest areas, water reservoirs, and watermills, highlight a communal management system ensuring fair and sustainable water sharing. This system stands as a remarkable testament to cultural traditions and civilizations adapting to arid desert climates.[31] |

| Historic City of Yazd |

|

Yazd, Yazd Province | Cultural:

(iii)(v) |

195.67 (483.5) | 2017 | Yazd, centrally located on the Iranian plateau, exemplifies desert survival with its Qanat water supply system. Preserving ancient earthen architecture, the city retains traditional districts, markets, religious sites, and the historic Dolat-abad garden.[32] |

| Hyrcanian Forests |

|

Golestan, Mazandaran and Gilan Provinces | Natural:

(ix) |

129,484.74 (319,963.8) | 2019 | Hyrcanian forest covered some parts of Three provinces of Iran including: Golestan Province: The entirety of the southern and southwestern areas as well as parts of the eastern regions of the Gorgan plain is covered with Hyrcanian forest, totaling an area.[33] |

| The Persian Caravanserai |

|

54 Location in Iran | Cultural:

(ii)(iii) |

27.77 | 2023 | Caravanserais were roadside inns, providing shelter, food and water for caravans, pilgrims and other travellers. The routes and the locations of the caravanserais were determined by the presence of water, geographical conditions and security concerns. The fifty-six caravanserais of the property are only a small percentage of the numerous caravanserais built along the ancient roads of Iran.[34] |

القائمة المحتملة

Iran (Persia) is a rich country in Culture, History and Natural heritage, home to one of the world's oldest civilizations, and known as Four Seasons Country.[35][36][37]

In addition to sites inscribed on the World Heritage list, member states can maintain a list of tentative sites that they may consider for nomination. Nominations for the World Heritage list are only accepted if the site was previously listed on the tentative list. As of May 2020, Iran has 56 properties on UNESCO's tentative list.[38]

| Name | Image | Location | Category

Criteria Reference |

Date | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali-Sadr Cave |

|

Hamadan Province | Natural

(vii)(viii)(ix) |

09/08/2007 | Ali Sadr Cave, famous for its vast water halls and an extraordinary array of speleothems like stalactites and stalagmites, along with various karst formations, boasts the largest water cave accessible by boat at about 2400 meters. This natural wonder is under a sustainable management system ensuring its conservation and use for future generations.[39] |

| Arasbaran Protected Area |

|

Azerbaijan Province | Natural

(vii)(viii)(ix)(x) |

09/08/2007 | The Arasbaran Protected Area in Iran spans 78,560 hectares with a 134 km perimeter. Its elevation ranges from approximately 256 m to 2896 m, creating a diverse habitat with a rich biodiversity encompassing around 1,000 plant and animal taxa. Significant for its rare species, including Lyurus mlokosiewiczi, the area was designated a conservation zone in 1971 and recognized by UNESCO as a wildlife refuge since 1976, becoming Iran’s 9th Biosphere Reserve.[40] |

| Asbaads (Windmill) of Iran.Nashtifan |

|

Khurasan-e Razavi, Sistan and Balochestan | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iv)(v) |

02/02/2017 | Strong Shamal winds persist year-round in eastern Iran, with exceptional “120 days winds” affecting areas like Sistan and Baluchistan, Southern Khorasan, and parts of Razavi Provinces, reaching speeds up to 100 km/hour. Utilizing this relentless wind and addressing the scarcity of water, the locals invented windmills called “Asbad” to harness wind energy for grinding grains. These windmills, significant to Iranian desert architecture, are strategically built on high elevations to efficiently capture wind without obstruction. Concentrated in regions with persistent winds, they not only grind grains but also act as barriers against storms for nearby settlements. Historically, the use of wind for mechanical energy dates back 3000 years in Iran and China, with the Iranian vertical-axis windmills spreading across the Islamic world and eventually influencing European windmill design.[41] |

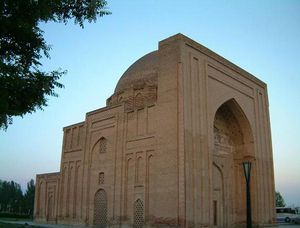

| Bastam and Kharghan |

|

Cultural

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

09/08/2007 | The assemblage includes Sheikh Bayazid Bastami’s complex, the Chief Mosque, Kashaneh’s towered dome, and part of the old city wall. Centered around the grave of Sheikh Bayazid Bastami, a renowned Sufi, the complex has attracted significant constructions since the 19th century. The oldest structures within the complex date to the 8th and 9th centuries AD.[42] | |

| Bazaar of Qaisariye in Laar | Laar, Fars Province | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(vi) |

09/08/2007 | Laar exemplifies urban planning from the pre-Safavid era, with its design showcasing resilience and adaptation after a major earthquake. The continuity and development of the Bazaar of Qaisariye, alongside the construction of a square featuring a polo gate and encircling porticos, illustrate a distinctive urban complex emerging from the reconstruction efforts post-disaster.[43] | |

| Cultural Landscape of Alamutt |

|

Village of Alamout,

Qazvin |

Mixed

(ii)(iv)(v)(vi)(viii) |

09/08/2007 | Hassan Sabah’s castle, located in northeastern Gazor Khan Village near Mo’alem Kalayeh in Roudbar of Alamout, is a historical fortress perched atop a 220-meter cliff, sitting 2163 meters above sea level on the southwestern slopes of the Houdkan Mountain range, part of the larger Alborz Mountains. The remaining structures, including walls, towers, and observation posts, are constructed from stone bonded with gypsum. Covering an area of ten thousand square meters, the castle’s buildings are strategically distributed across the different elevations of the rugged terrain, making efficient use of the steep and challenging topography. The 7th-century historian Ata Malak Joveyni likened the cliff’s profile to a sleeping camel, while explorer Freya Stark described its summit as resembling the prow of a ship pointing northwest.[44] |

| Damavand |

|

Mazandaran Province | Natural

(vii)(viii)(ix)(x) |

05/02/2008 | Mount Damavand, standing at approximately 5,628 meters above sea level, is Iran’s tallest peak and an inactive volcano that saw activity during the Quaternary period. This iconic mountain is known for its numerous thermal springs, like Ask and Larijan, and for being perpetually snow-capped throughout the year. The region boasts a rich biodiversity, encompassing around 2,000 plant species, including a variety of endemic species that are of great significance to the global flora.[45] |

| Firuzabad Ensemble |

|

Firuzabad, Fars | Cultural | 22/05/1997 | The Firuzabad ensemble, within a 12 km zone, encapsulates the rich history of the Sassanian period through pivotal structures such as the circular City of Gur, the nearby Palace of Ardashir by the Tangab river, and the strategically placed Qal’eh Dokhtar fortress. It also hosts significant art in the form of bas reliefs depicting the era’s notable events and the Pahlavi inscription of Mehr-Nerse. These elements collectively highlight the empire’s advanced urban planning and architectural sophistication.[46] |

| Ghaznavi- Seljukian Axis in Khorasan |

|

Khorasan Province | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

09/08/2007 | Numerous caravanserais along the Silk Route, dating back to the Seljuk period, such as Robat-Sharaf and Robat-Mahi, along with historical complexes like Sang-bast and constructions like the Baba Loghman Building, underscore the importance of this trade artery in both the Great Khorasan of yesteryears and the contemporary Khorasan region.[47] |

| Hamoun Lake |

|

Sistan and Baluchistan Province | Natural

(vii)(viii)(ix)(x) |

05/02/2008 | This eastern desert lake is divided into three zones: Hamoun-Hirmand to the south and southwest, Hamoun-e-Sabereen to the northwest, and Hamoun-e-Pouzak to the northeast of the Sistan Plain. During high-precipitation seasons, the lake spans approximately 5,700 km², with 3,800 km² lying within Iranian borders and the remainder in Afghanistan.[48] |

| Harra Protected Area |

|

Hormozgan Province | Natural

(vii)(viii)(ix)(x) |

05/02/2008 | The Khuran Strait reserve lies between Qeshm Island and southern Iran, featuring the Mehran delta with its extensive intetidal flats and the region’s largest stand of Harra mangroves (Avicennia marina). Hosting a subtropical climate with very hot summers and sparse rainfall, it’s crucial for various water birds’ life cycles. Protectively marked in 1972 and recognized as a Ramsar Site and biosphere reserve by 1976, the area spans over 82,360 hectares of mangroves and mudflats.[49] |

| Ecbatana |

|

Hamadan Province | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

05/02/2008 | |

| Historic ensemble of Qasr-e Shirin |

|

Qasr-e Shrin, Kermanshah Province | Cultural | 22/05/1997 | |

| Temple of Anahita of Kangavar |

|

Kangavar, Kermanshah Province | Cultural

(iii) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Imam Reza Shrine |

|

Mashhad, Khurasan-e Razavi Province | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(vi) |

02/02/2017 | |

| Industrial Heritage of textile in the central Plateau of Iran | Isfahan, Yazd and Kerman Provinces | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

02/02/2017 | ||

| Jiroft |

|

Kerman Province | Cultural

(ii)(iii)(v)(vi) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Blue Mosque, Tabriz |

|

Tabriz, East Azerbaijan Province | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Kerman Historical-Cultural Structure |

|

Kerman Province | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(vi) |

05/02/2008 | |

| Khabr National Park and Ruchun Wildlife Refuge |

|

Kerman Province | Natural

(vii)(viii)(ix)(x) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Khorramabad Valley |

|

Khorramabad, Luristan Province | Cultural

(i)(iii)(iv)(v) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Mount Khajeh |

|

Zabol, Sistan and Baluchistan Province | Cultural

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Naqsh-e Rostam and Naqsh-e Rajab |

|

Marvdasht, Fars Province | Cultural | 22/05/1997 | |

| Natural-Historical Complex / Cave of Karaftoo | Kurdistan Province | Mixed | 02/02/2017 | ||

| Persepolis and other relevant buildings |

|

Fars Province | Cultural | 09/08/2007 | |

| Persian Caravanserai |

|

Khurasan-e Razavi, Isfahan and Yazd Provinces | Cultural | 02/02/2017 | |

| Qeshm Island |

|

Hormozgan province | Natural | 09/08/2007 | |

| Sabalan |

|

Ardabil Province | Natural | 09/08/2007 | |

| Salt Domes of Iran | Fars Province, Bushehr, Hormozgan, Qom and Zanjan | Natural | 02/02/2017 | ||

| Shush |

|

100 km south of Ahvaz, Khuzestan province | Cultural | 22/05/1997 | |

| Silk Route (Also as Silk Road) | Khorasan Province | Cultural

(i) |

05/02/2008 | ||

| Tepe Sialk |

|

Isfahan Province | Cultural | 22/05/1997 | |

| Taq-e Bostan |

|

Kermanshah, Kermanshah Province | Cultural | 09/08/2007 | |

| The Collection of Historical Bridges |

|

Lorestan Province | Cultural | 05/02/2008 | |

| The Complex of Izadkhast |

|

Fars Province | Cultural | 09/08/2007 | |

| The Cultural-Natural Landscape of Ramsar |

|

City of Ramsar, Province of Mazandaran | Mixed | 09/08/2007 | |

| The Great Wall of Gorgan | Golestan Province | Cultural | 02/02/2017 | ||

| The Historical City of Masuleh |

|

City of Masouleh, Gilan Province | Cultural | 09/08/2007 | |

| The Historical City of Maybod |

|

Maybod, Yazd Province | Cultural | 09/08/2007 | |

| The Historical Port of Siraf |

|

Province of Bushehr | Cultural

(v) |

09/08/2007 | |

| The Historical Texture of Damghan |

|

Semnan Province | Cultural

(ii)(iii)(iv)(v) |

09/08/2007 | |

| The Historical Village of Abyaneh |

|

Village of Abyaneh, Isfahan Province | Cultural

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

09/08/2007 | |

| Agha Bozorg Mosque |

|

Isfahan Province, Kashan | Cultural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(vi) |

09/08/2007 | |

| The Natural-Historical Landscape of Izeh |

|

Khuzestan Province | Natural

(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(v)(vi) |

05/02/2008 | |

| The Persian House in Central plateau of Iran |

|

Isfahan and Yazd Provinces | Cultural

(ii)(iv)(v)(vi) |

02/02/2017 | |

| The Zandiyeh Ensemble of Fars Province |

|

Shiraz, Fars Province | Cultural

(vi) |

05/02/2008 | |

| Touran Biosphere Reserve |

|

Semnan Province | Natural

(x) |

05/02/2008 | |

| Tus Cultural Landscape |

|

Tous, Khorasan Province | Cultural

(iii)(iv)(vi) |

02/02/2017 | |

| جامعة طهران |

|

Tehran Province | Cultural

(ii)(vi) |

02/02/2017 | |

| Zozan |

|

Province of Khorasan | Cultural

(ii)(iii)(iv) |

09/08/2007 |

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ أ ب "Iran". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "The World Heritage Convention". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "Report of the 3rd Session of the Committee". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Report of the 27th Session of the Committee". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Tentative List – Iran". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "World Heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ "The Criteria for Selection". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ "Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Bam and its Cultural Landscape". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Bisotun". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Cultural Landscape of Maymand". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Cultural Landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat". UNESCO. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Gonbad-e Qābus". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Golestan Palace". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ "Lut Desert". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region". UNESCO. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ "Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Meidan Emam, Esfahan". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Pasargadae". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Persepolis". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Shahr-e Sukhteh". UNESCO. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Sheikh Safi al-din Khānegāh and Shrine Ensemble in Ardabil". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Soltaniyeh". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Susa". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Takht-e Soleyman". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Tchogha Zanbil". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "The Persian Garden". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Trans-Iranian Railway". UNESCO. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "The Persian Qanat". UNESCO. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Historic City of Yazd". UNESCO. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ "Hyrcanian forests". UNESCO. Retrieved 27 Aug 2019.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "The Persian Caravanserai". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ Whatley, Christopher (2001). Bought and Sold for English Gold: The Union of 1707. Tuckwell Press.

- ^ Lowell Barrington (2012). Comparative Politics: Structures and Choices, 2nd ed.tr: Structures and Choices. Cengage Learning. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-111-34193-0. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Country of Four Seasons: Iran a World inside a Country - Tourism news".

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Tentative Lists".

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Alisadr Cave". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Arasbaran Protected Area". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Asbads (windmill) of Iran". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Bastam and Kharghan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Bazaar of Qaisariye in Laar". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Cultural Landscape of Alamout". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Damavand". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Firuzabad Ensemble". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Ghaznavi- Seljukian Axis in Khorasan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Hamoun Lake". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Harra Protected Area". UNESCO World Heritage Centre (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- unesco-world-heritage-sites-Iran [1]