سلاڤ

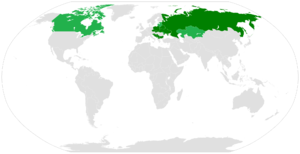

World map of countries with: Majority Slavic ethnicities (More than 50%) Minority Slavic populations (10–50%) | |

| إجمالي التعداد | |

|---|---|

| ح. 300 مليون | |

| المناطق ذات التجمعات المعتبرة | |

| ح. 134 مليون | |

| ح. 60 مليون | |

| ح. 59 مليون | |

| ح. 14 مليون | |

| ح. 10 مليون | |

| ح. 10 مليون | |

| ح. 7 مليون | |

| ح. 8 مليون | |

| ح. 7 مليون | |

| ح. 5 مليون | |

| ح. 3 مليون | |

| ح. 2.5 مليون | |

| ح. 2.4 million | |

| ح. 1.7 million | |

| ح. 1 million [1] | |

| ح. 860,000 | |

| ح. 700,000 | |

| ح. 570,000 | |

| ح. 460,000 | |

| ح. 415,000 | |

| ح. 150,000 | |

| ح. 140,000 | |

| ح. 67,000 | |

| ح. 60,000 | |

| ح. 20,000 | |

| ح. 6,000 | |

| ح. 5,000 | |

| ح. 600 | |

| ? | |

| ? | |

| اللغات | |

| اللغات السلافية | |

| الدين | |

| Majority: Minority: المسيحية الروحانية لا دين | |

| الجماعات العرقية ذات الصلة | |

| Balts | |

الشعب السلاڤي ينتمي إلى الجماعة اللغوية العرقية الهندو-اوروبية ويقطن اوروبا الوسطى والشرقية وجنوب شرق اوروبا، شمال آسيا وآسيا الوسطى، ويتكلمون اللغات السلاڤية الهندو-اوروبية، ويتشاركون، بدرجات متفاوتة، في عادات ثقافية وخلفيات تاريخية معينة. وقد انتشروا منذ مطلع القرن السادس ليسكنوا معظم وسط وشرق اوروبا والبلقان.[2] وبالاضافة لتمركزهم الرئيسي في اوروبا، فقد استوطن بعض السلاڤ الشرقيين (الروس) لاحقاً في سيبريا[3] وآسيا الوسطى.[4] وقد هاجر جزء من الأعراق السلاڤية إلى أجزاء أخرى من العالم.[5][6] ويقطن أكثر من نصف أراضي اوروبا مجتمعات ناطقة بلغات سلاڤية.[7] ويبلغ التعداد العالمي للمنحدرين من أصول سلاڤية ما يقرب من 400 مليون نسمة، مما يجعلهم رابع أكبر عرق جامع في العالم.

الأمم والجماعات العرقية الحالية التي يضمها اسم العرق سلاڤ تتنوع وراثياً وثقافياً والعلاقات بينهم – حتى داخل الجماعة العرقية المفردة – تتباين، وتتراوح من حس بالترابط وحتى الكراهية المتبادلة.[8]

الشعب السلاڤي الحالي يُصنـَّف إلى سلاڤ شرقيين (ويضمون الروس، الاوكرانيين، والبلاروس)، سلاڤ غربيين (ويضمون الپولنديين، التشيك، السلوڤاك والسيليز),[9] و سلاڤ جنوبيين (ويضمون البلغار، المقدونيين، السلوڤين، الكروات، البوشناق والصرب والمونتنگرين). ولقائمة أكثر تفصيلاً، انظر التقسيمات العرقية الثقافية.

اسم العرق

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| المواضيع الهندو-أوروپية |

|---|

|

الاسم الذاتي السلاڤي أعيد تركيبه في السلاڤية الأولى في الصيغة Slověninъ. أقدم الوثائق المكتوبة بالسلاڤونية الكنسية القديمة والتي تعود إلى القرن التاسع تشهد بأن كلمة Словѣне Slověne تصف السلاڤ. الشواهد السلاڤية المبكرة الأخرى تحوي الكلمة السلاڤية الشرقية القديمة Словѣнѣ Slověně لتشير إلى "جماعة سلاڤية شرقية بالقرب من نوڤگورود." إلا أن أقدم اشارات مكتوبة للسلاڤ بهذا الاسم توجد في لغات أخرى. ففي القرن السادس الميلادي، يشير پروكوپيوس، في كتاباته باللغة اليونانية البيزنطية، إلى Σκλάβοι Sklaboi، Σκλαβηνοί Sklabēnoi، Σκλαυηνοί Sklauenoi, Σθλαβηνοί Sthlauenoi، أو Σκλαβῖνοι Sklabinoi,[10] بينما يشير معاصره جوردانس إلى Sclaveni باللاتينية.[11]

الاسم الذاتي السلاڤي Slověninъ is usually considered a derivation from slovo "word," originally denoting "people who speak (the same language)," i.e. people who understand each other, in contrast to the Slavic word denoting "foreign people" – němci, meaning "mumbling, murmuring people" (from Slavic němъ – "mumbling, mute"). The latter word may be the derivation of words to denote German/Germanic people in many later Slavic languages: e.g., Czech Němec, Slovak Nemec, Slovene Nemec, Belarusian, Russian and Bulgarian Немец, Serbian Немац, Serbian, Bosnian وCroatian Nijemac, Polish Niemiec, Ukrainian Німець, etc.,[12] but another theory states that rather these words are derived from the name of the Nemetes tribe,[13][14] which مشتقة من الجذر الكلتي nemeto-.[15][16]

الكلمة الإنگليزية Slav مشتقة من الكلمة الإنگليزية الوسطى sclave، التي كانت مستعارة من لاتينية القرون الوسطى sclavus "slave,"[17] itself a borrowing and Byzantine Greek σκλάβος sklábos "slave," which was in turn apparently derived from a misunderstanding of the Slavic autonym (denoting a speaker of their own languages). The Byzantine term Sklavinoi was loaned into Arabic as Saqaliba by medieval Arab historiographers.[بحاجة لمصدر] However, the origin of this word is disputed.[18][19]

Alternative proposals for the etymology of Slověninъ propounded by some scholars enjoy much less support. B.P. Lozinski argues that the word slava once had the meaning of worshipper, in this context meaning "practicer of a common Slavic religion," and from that evolved into an ethnonym.[20] S.B. Bernstein speculates that it derives from a reconstructed Proto-Indo-European *(s)lawos, cognate to Ancient Greek λαός laós "population, people," which itself has no commonly accepted etymology.[21] Meanwhile others have pointed out that the suffix -enin indicates a man from a certain place, which in this case should be a place called Slova or Slava, possibly a river name. The Old East Slavic Slavuta for the Dnieper River was argued by Henrich Bartek (1907–1986) to be derived from slova and also the origin of Slovene.[22]

Last scientific opinions about the earliest mentions of Slavic raids across the Lower Danube River show that they may be dated to the first half of the sixth century, yet no archaeological evidence of a Slavic settlement in the Balkans could be securely dated before ca. 600 [23][24][25]

التاريخ

نقاش حول السلاڤ المبكرين

هناك نظرية تخبر أن الهندو أوروبييين الأوائل وكذلك السلاف الأوائل تعود أصولهم إلى السهول الروسية الموجودة في المنطقة الواقعة في أوكرانيا والأجزاء الجنوبية من روسيا (انظر فرضيات كورجان). يرى بعض علماء التاريخ أن موطن السلاف الأوائل هو أوروبا الوسطى منذ تاريخ سحيق وأنهم هم أصحاب الثقافة اللوساتية وثقافة برزي ورسك وكان جزءا من الحضارة تشيرنايخوف وهذا الرأي لا يناقض فرضيات كورجان كثيرا.

الأصول

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| المواضيع الهندو-أوروپية |

|---|

|

جدل الموطن الأصلي

- Milograd culture hypothesis: The pre-Proto-Slavs (or Balto-Slavs) were the bearers of the Milograd culture (7th century BCE to 1st century CE) of northern Ukraine and southern Belarus.

- Chernoles culture hypothesis: The pre-Proto-Slavs were the bearers of the Chernoles culture (750–200 BCE) of northern Ukraine, and later the Zarubintsy culture (3rd century BCE to 1st century CE).

- Lusatian culture hypothesis: The pre-Proto-Slavs were present in north-eastern Central Europe since at least the late 2nd millennium BCE, and were the bearers of the Lusatian culture (1300–500 BCE), and later the Przeworsk culture (2nd century BCE to 4th century CE).

- Danube basin hypothesis: postulated by Oleg Trubachyov;[26] sustained at present by Florin Curta,[27] also supported by an early Medieval Slavic narrative source - Nestor's Chronicle

أول ذِكر

ذكر كل من پلني الأكبر وپطليموس قبيلة Veneti, who dwelt in a region of central Europe east of the Germanic tribe of Suebi, and west of the Iranian Sarmatians in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD,[29][30] between the upper Vistula and Dnieper rivers. The Slavs under name of the Antes and the Sclaveni first appear in Byzantine records in the early 6th century. Byzantine historiographers under emperor Justinian I (527–565), such as Procopius of Caesarea, Jordanes and Theophylact Simocatta describe tribes of these names emerging from the area of the Carpathian Mountains, the lower Danube and the Black Sea, invading the Danubian provinces of the Eastern Empire.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Jordanes, in his work Getica (written in 551 AD),[31] describes the Veneti as a "populous nation" whose dwellings begin at the sources of the Vistula and occupy "a great expanse of land". He also describes the Veneti as the ancestors of Antes and Slaveni, two early Slavic tribes, who appeared on the Byzantine frontier in the early 6th century.

Procopius wrote in 545 that "the Sclaveni and the Antae actually had a single name in the remote past; for they were both called Sporoi in olden times". The name Sporoi derives from Greek σπείρω ("to sow"). He described them as barbarians, who lived under democracy, believed in one god, "the maker of lightning" (Perun), to whom they made a sacrifice. They lived in scattered housing and constantly changed settlement. In war, they were mainly foot soldiers with shields, spears, bows, and little armour, which was reserved mainly for chiefs and their inner circle of warriors.[32] Their language is "barbarous" (that is, not Greek), and the two tribes are alike in appearance, being tall and robust, "while their bodies and hair are neither very fair or blond, nor indeed do they incline entirely to the dark type, but they are all slightly ruddy in color. And they live a hard life, giving no heed to bodily comforts..."[33]

Jordanes described the Sclaveni having swamps and forests for their cities.[34] Another 6th-century source refers to them living among nearly-impenetrable forests, rivers, lakes, and marshes.[35]

Menander Protector mentions a Daurentius (c. 577–579) who slew an Avar envoy of Khagan Bayan I for asking the Slavs to accept the suzerainty of the Avars; Daurentius declined and is reported as saying: "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs – so it shall always be for us as long as there are wars and weapons".[36]

العصور الوسطى

When Slav migrations ended, their first state organizations appeared, each headed by a prince with a treasury and a defense force. In the 7th century, the Frankish merchant Samo supported the Slavs against their Avar rulers and became the ruler of the first known Slav state in Central Europe, Samo's Empire. This early Slavic polity probably did not outlive its founder and ruler, but it was the foundation for later West Slavic states on its territory.

The oldest of them was Carantania; others are the Principality of Nitra, the Moravian principality (see under Great Moravia) and the Balaton Principality. The First Bulgarian Empire was founded in 681 as an alliance between the ruling Bulgars and the numerous Slavs in the area, and their South Slavic language, the Old Church Slavonic, became the main and official language of the empire in 864. Bulgaria was instrumental in the spread of Slavic literacy and Christianity to the rest of the Slavic world. Duchy of Croatia was founded in 9th century and later became Kingdom of Croatia. Principality of Serbia was founded in 8th, Duchy of Bohemia and Kievan Rus' both in the 9th century.

The expansion of the Magyars into the Carpathian Basin and the Germanization of Austria gradually separated the South Slavs from the West and East Slavs. Later Slavic states, which formed in the following centuries included the Second Bulgarian Empire, the Kingdom of Poland, Banate of Bosnia, Duklja and Kingdom of Serbia which later grew into Serbian Empire.[بحاجة لمصدر]

العصر الحديث

Pan-Slavism, a movement which came into prominence in the mid-19th century, emphasized the common heritage and unity of all the Slavic peoples. The main focus was in the Balkans where the South Slavs had been ruled for centuries by other empires: the Byzantine Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice. Austro-Hungary envisioned its own political concept of Austro-Slavism, in opposition of Pan-Slavism that was predominantly led by the Russian Empire. [37]

As of 1878, there were only three majority Slavic states in the world: the Russian Empire, Principality of Serbia and Principality of Montenegro. Bulgaria was effectively independent but was de jure vassal to the Ottoman Empire until official independence was declared in 1908. The Slavic peoples who were, for the most part, denied a voice in the affairs of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, were calling for national self-determination. During World War I, representatives of the Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes set up organizations in the Allied countries to gain sympathy and recognition.[38] In 1918, after World War I ended, the Slavs established such independent states as Czechoslovakia, the Second Polish Republic, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

One of Hitler's ambitions at the start of World War II was to exterminate, expel, or enslave most or all East and West Slavs from their native lands, so as to make living space for German settlers. This plan of genocide[39] was to be carried into effect gradually over 25 to 30 years. The first half of the 20th century in Russia and the Soviet Union was marked by a succession of wars, famines and other disasters, each accompanied by large-scale population losses.[40] Stephen J. Lee estimates that, by the end of World War II in 1945, the Russian population was about 90 million fewer than it could have been otherwise.[41]

Former Soviet states in Central Asia such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have very large minority Slavic populations with most being Russians.[42] Kazakhstan has the largest Slavic minority population.[43]

اللغات

Proto-Slavic, the supposed ancestor language of all Slavic languages, is a descendant of common Proto-Indo-European, via a Balto-Slavic stage in which it developed numerous lexical and morphophonological isoglosses with the Baltic languages. In the framework of the Kurgan hypothesis, "the Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations [from the steppe] became speakers of Balto-Slavic".[44]

Proto-Slavic is defined as the last stage of the language preceding the geographical split of the historical Slavic languages. That language was uniform, and on the basis of borrowings from foreign languages and Slavic borrowings into other languages, it cannot be said to have any recognizable dialects, which suggests that there was, at one time, a relatively-small Proto-Slavic homeland.[45]

Slavic linguistic unity was to some extent visible as late as Old Church Slavonic (or Old Bulgarian) manuscripts which, though based on local Slavic speech of Thessaloniki, could still serve the purpose of the first common Slavic literary language.[46]

Standardised Slavic languages that have official status in at least one country are: Belarusian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Polish, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovene, and Ukrainian. Russian is the most spoken Slavic language, and is the most spoken native language in Europe.[47]

The alphabets used for Slavic languages are usually connected to the dominant religion among the respective ethnic groups. Orthodox Christians use the Cyrillic alphabet while Catholics use the Latin alphabet; the Bosniaks, who are Muslim, also use the Latin alphabet and Cyrillic alphabet in Serbia. Additionally, some Eastern Catholics and Western Catholics use the Cyrillic alphabet. Serbian and Montenegrin use both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. There is also a Latin script to write in Belarusian, called Łacinka and in Ukrainian, called Latynka.[بحاجة لمصدر]

التقسيمات العرقية-الثقافية

West Slavs originate from early Slavic tribes which settled in Central Europe after the East Germanic tribes had left this area during the migration period.[48] They are noted as having mixed with Germanics, Hungarians, Celts (particularly the Boii), Old Prussians, and the Pannonian Avars.[49] The West Slavs came under the influence of the Western Roman Empire (Latin) and of the Catholic Church.[بحاجة لمصدر]

East Slavs have origins in early Slavic tribes who mixed and contacted with Finns, Balts[50][51] and with the remnants of the people of the Goths.[52] Their early Slavic component, Antes, mixed or absorbed Iranians, and later received influence from the Khazars and Vikings.[53] The East Slavs trace their national origins to the tribal unions of Kievan Rus' and Rus' Khaganate, beginning in the 10th century. They came particularly under the influence of the Byzantine Empire and of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[بحاجة لمصدر]

South Slavs from most of the region have origins in early Slavic tribes who mixed with the local Proto-Balkanic tribes (Illyrian, Dacian, Thracian, Paeonian, Hellenic tribes), and Celtic tribes (particularly the Scordisci), as well as with Romans (and the Romanized remnants of the former groups), and also with remnants of temporarily settled invading East Germanic, Asiatic or Caucasian tribes such as Gepids, Huns, Avars, Goths and Bulgars.[بحاجة لمصدر] The original inhabitants of present-day Slovenia and continental Croatia have origins in early Slavic tribes who mixed with Romans and romanized Celtic and Illyrian people as well as with Avars and Germanic peoples (Lombards and East Goths). The South Slavs (except the Slovenes and Croats) came under the cultural sphere of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire), of the Ottoman Empire and of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Islam, while the Slovenes and the Croats were influenced by the Western Roman Empire (Latin) and thus by the Catholic Church in a similar fashion to that of the West Slavs.[بحاجة لمصدر]

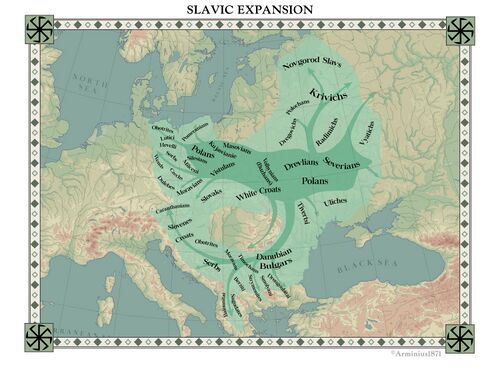

الهجرات السلاڤية

الجينات

Consistent with the proximity of their languages, analyses of Y chromosomes, mDNA, and autosomal marker CCR5de132 shows that East Slavs and West Slavs are genetically very similar, but demonstrating significant differences from neighboring Finno-Ugric, Turkic, and North Caucasian peoples. Such genetic homogeneity is somewhat unusual, given such a wide dispersal of Slavic populations, especially Russians.[54][55] Together they form the basis of the "East European" gene cluster, which also includes non-Slavic Hungarians and Aromanians.[54][56]

Only Northern Russians among East and West Slavs belong to a different, "Northern European" genetic cluster, along with Balts, Germanic and Baltic Finnic peoples (Northern Russian populations are very similar to Balts).[57][58]

The 2006 Y-DNA study results "suggest that the Slavic expansion started from the territory of present-day Ukraine, thus supporting the hypothesis placing the earliest known homeland of Slavs in the basin of the middle Dnieper".[59] According to genetic studies until 2020, the distribution, variance and frequency of the Y-DNA haplogroups R1a and I2 and their subclades R-M558, R-M458 and I-CTS10228 among South Slavs correlate with the spread of Slavic languages during the medieval Slavic expansion from Eastern Europe, most probably from the territory of present-day Ukraine and Southeastern Poland.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

التعداد

The worldwide population of people of Slavic descent is close to 400 million. The three largest Slavic ethnic groups are Russians (150 million), Poles, and Ukrainians (50 million). Other Slavic ethnic groups include Czechs (11 million), Serbs (10,5 million), Bulgarians (10 million), Belarusians (10 million), Croats (8 million), Slovaks (7 million), Silesians (5 million), Bosniaks (3 million), Macedonians (3 million), Slovenes (2,5 million), Montenegrins (700 000). Polish and Serbians make up the largest Slavic populations or Slavic-descended American population in the United States.

الدين

The pagan Slavic populations were Christianized between the 7th and 12th centuries. Orthodox Christianity is predominant among East and South Slavs, while Catholicism is predominant among West Slavs and some western South Slavs. The religious borders are largely comparable to the East–West Schism which began in the 11th century. Islam first arrived in the 7th century during the early Muslim conquests, and was gradually adopted by a number of Slavic ethnic groups through the centuries in the Balkans.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Among Slavic populations who profess a religion, the majority of contemporary Christian Slavs are Orthodox, followed by Catholic. The majority of Muslim Slavs follow the Hanafi school of the Sunni branch of Islam.[67] Religious delineations by nationality can be very sharp; usually in the Slavic ethnic groups, the vast majority of religious people share the same religion.[بحاجة لمصدر]

|

Mainly Eastern Orthodoxy:[68][69] |

Mainly Catholicism:[بحاجة لمصدر]

|

Mainly Islam:

|

العلاقة بالشعوب غير السلاڤية

Throughout their history, Slavs came into contact with non-Slavic groups. In the postulated homeland region (present-day Ukraine), they had contacts with the Iranian Sarmatians and the Germanic Goths. After their subsequent spread, the Slavs began assimilating non-Slavic peoples. For example, in the Northern Black Sea region, the Slavs assimilated the remnants of the Goths.[76] In the Balkans, there were Paleo-Balkan peoples, such as Romanized and Hellenized (Jireček Line) Illyrians, Thracians and Dacians, as well as Greeks and Celtic Scordisci and Serdi.[77] Because Slavs were so numerous, most indigenous populations of the Balkans were Slavicized. Thracians and Illyrians mixed as ethnic groups in this period.

A notable exception is Greece, where Slavs were Hellenized because Greeks were more numerous, especially with more Greeks returning to Greece in the 9th century and the influence of the church and administration,[78] however, Slavicized regions within Macedonia, Thrace and Moesia Inferior also had a larger portion of locals compared to migrating Slavs.[79] Other notable exceptions are the territory of present-day Romania and Hungary, where Slavs settled en route to present-day Greece, North Macedonia, Bulgaria and East Thrace but assimilated, and the modern Albanian nation which claims descent from Illyrians and other Balkan tribes.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The status of the Bulgars as a ruling class and their control of the land nominally left their legacy in the Bulgarian country and people, but Bulgars were gradually also Slavicized into the present-day South Slavic ethnic group known as Bulgarians. The Romance speakers within the fortified Dalmatian cities retained their culture and language for a long time.[80] Dalmatian Romance was spoken until the high Middle Ages, but, they too were eventually assimilated into the body of Slavs.[81]

In the Western Balkans, South Slavs and Germanic Gepids intermarried with invaders, eventually producing a Slavicized population.[بحاجة لمصدر] In Central Europe, the West Slavs intermixed with Germanic, Hungarian, and Celtic peoples, while in Eastern Europe the East Slavs had encountered Finnic and Scandinavian peoples. Scandinavians (Varangians) and Finnic peoples were involved in the early formation of the Rus' state but were completely Slavicized after a century. Some Finno-Ugric tribes in the north were also absorbed into the expanding Rus population.[82] In the 11th and 12th centuries, constant incursions by nomadic Turkic tribes, such as the Kipchak and the Pecheneg, caused a massive migration of East Slavic populations to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north.[83] In the Middle Ages, groups of Saxon ore miners settled in medieval Bosnia, Serbia and Bulgaria, where they were Slavicized.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Saqaliba refers to the Slavic mercenaries and slaves in the medieval Arab world in North Africa, Sicily and Al-Andalus. Saqaliba served as caliph's guards.[84][85] In the 12th century, Slavic piracy in the Baltics increased. The Wendish Crusade was started against the Polabian Slavs in 1147, as a part of the Northern Crusades. The pagan chief of the Slavic Obodrite tribes, Niklot, began his open resistance when Lothar III, Holy Roman Emperor, invaded Slavic lands. In August 1160 Niklot was killed, and German colonization (Ostsiedlung) of the Elbe-Oder region began. In Hanoverian Wendland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lusatia, invaders started germanization. Early forms of germanization were described by German monks: Helmold in the manuscript Chronicon Slavorum and Adam of Bremen in Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum.[86] The Polabian language survived until the beginning of the 19th century in what is now the German state of Lower Saxony.[87] In Eastern Germany, around 20% of Germans have historic Slavic paternal ancestry, as revealed in Y-DNA testing.[88] Similarly, in Germany, around 20% of the foreign surnames are of Slavic origin.[89]

Cossacks, although Slavic and practicing Orthodox Christianity, came from a mix of ethnic backgrounds, including Tatars and other peoples. Initially, the Cossacks were a mini-subethnos, but now they are less than 5%, and most of them live in the south of Russia.[بحاجة لمصدر] The Gorals of southern Poland and northern Slovakia are partially descended from Romance-speaking Vlachs, who migrated into the region from the 14th to 17th centuries and were absorbed into the local population. The population of Moravian Wallachia also descended from the Vlachs. Conversely, some Slavs were assimilated into other populations. Although the majority continued towards Southeast Europe, attracted by the riches of the area that became the state of Bulgaria, a few remained in the Carpathian Basin in Central Europe and were assimilated into the Magyar people. Numerous rivers and places in Romania have a name with Slavic origins.[90]

الأبجدية

The alphabet depends on what religion is usual for the respective Slavic ethnic groups. The Orthodox use the Cyrillic alphabet and the Roman Catholics use Latin alphabet, the Bosniaks which are Muslims also use the Latin. Few Greek Roman and Roman Catholics use the Cyrillic alphabet however. The Serbian language, Montenegrin language and Macedonian language can be written using both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets, but the Cyrillic remains preferred by a large majority. There is also a Latin script to write in Belarusian, called the Lacinka alphabet.

اللغة

Slavic studies began as an almost exclusively linguistic and philological enterprise. As early as 1833, Slavic languages were recognized as Indo-European.[27]

Slavic standard languages which are official in at least one country:

- Belarusian

- Bosnian

- Bulgarian

- Croatian

- Czech

- Macedonian

- Montenegrin

- Polish

- Russian

- Serbian

- Silesian

- Slovak

- Slovene

- Ukrainian

اللغة السلاڤية الأولى

مقالة مفصلة: اللغة السلاڤية الأولى

مقالة مفصلة: اللغة السلاڤية الأولى

التقسيمات العرقية الثقافية

Slavs are customarily divided along geographical lines into three major subgroups: East Slavs, West Slavs, and South Slavs, each with a different and a diverse background based on unique history, religion and culture of particular Slavic group within them. The East Slavs may all be traced to Slavic-speaking populations that were loosely organized under the Kievan Rus' empire beginning in the 10th century AD.

|

1. ذوو الأغلبية الارثوذكسية الشرقية أو/و كاثوليكية اليونانية: |

2. ذوو الأغلبية الكاثوليكية الرومانية مع أقليات صغيرة من البروتستانت والارثوذكسية الشرقية: |

3. ذوو الأغلبية المسلمة: 4. مختلطو الدين: 5. Those who are mainly atheist and Roman Catholic with Protestant minorities:

|

التقسيمات العرقية الثقافية

سلاڤ شرقيون

المقالة الرئيسية: السلاڤ الشرقيون

سلاڤ غربيون

مقال رئيسي: سلاڤ غربيون

- Lechitic group

- پولنديون

- Silesians 5

- Pomeranians

- Polabians †

- Sorbs

- Obodrites/Abodrites

- Veleti (Wilzi, later Liutici)†

- Ucri (Ukr(an)i, Ukranen)†

- Rani (Rujani)†

- Hevelli (Stodorani)†

- Volinians (Velunzani) †

- Pyritzans (Prissani) †

- المجموعة التشيكية السلوڤاكية

- Sorbs (Serbo-Lusatians)

سلاڤ جنوبيون

المقالة الرئيسية: السلاڤ الجنوبيون

- المجموعة (بلگارو-مقدونية) الشرقية

- المجموعة الغربية

- سلوڤين

- الصرب

- Montenegrins9

- كروات

- Janjevci (Catholic Slavs in Kosovo)

- Molise Croats (في شرق إيطاليا)

- Krashovans (كروات في رومانيا)

- Burgenland Croats (in Austria)

- Bunjevci 10

- Šokci 10

- Bunjevci 10

- بوشناق

- گوراني 11

- Yugoslavs (mostly in Serbia, Bosnia, few in Croatia) 13

† انقرضوا

1 Also considered part of Rusyns

2 Considered transitional between Ukrainians and Belarusians

3 Also considered part of Ukrainians

4 A part of Lemkos identify themselves as Ukrainians and another part as Rusyns [1]

5 Also considered part of Poles

6 Today, often considered part of Czechs, originally closer to Slovaks

7 Most Shopi self-declare as Bulgarians. Cognate with Torlaks.

8 Most Torlaks self-declare as Serbs. Cognate with Shopi.

9 Half of the Montenegrins opt Serb ethnicity, with a historical tradition, dating back to the Serb tribes that settled Montenegro many centuries ago. While others opt for Montenegrin ethnicity, are followers of the same Serbian Orthodox Church, speak the same language but do not have a historical tradition (prior to 1948 Montenegrin was used solely as a regional affiliation of a Serb, meaning a Serb from Montenegro). A small number of ethnic Montenegrins, mostly supporters of Montenegrin independence and adherents of the small Montenegrin Orthodox Church call their native language Montenegrin, considering it a separate language from Serbian.

10 Both occur widely in northeastern Croatia and also in northern Serbia; their Ikavian dialect is subequal as southern Croats in Hercegovina and Dalmatian mainland from where they once emigrated. Considered part of Croats by most of them, although recently (since Yugoslav disaster) some within Serbia consider themselves a separate peoples

11 These Gorani are Slavs in Kosovo; but not to be confound with other Gorani (or Gorinci) in the highlands of western Croatia (Gorski Kotar county).

12 A census category recognized as an ethnic group. Most Slavic Muslims now opt for Bosniak ethnicity, but some still use the "Muslim" designation.

13 This identity continues to be used by a minority throughout the former Yugoslav republics. The nationality is also declared by diasporans living in the USA and Canada. There are a multitude of reasons as to why people prefer this affiliation, some published on the article.

Note: Besides ethnic groups, Slavs often identify themselves with the local geographical region in which they live. Some of the major regional South Slavic groups include: Zagorci in northern Croatia, Istrani in westernmost Croatia, Dalmatinci in southern Croatia, Boduli in Adriatic islands, Slavonci in eastern Croatia, Bosanci in Bosnia, Hercegovci in southern Bosnia (Herzegovina), Krajišnici in western Bosnia, Semberci in northeast Bosnia, Srbijanci in Serbia proper, Šumadinci in central Serbia, Vojvođani in northern Serbia, Sremci in Syrmia, Bačvani in northwest Vojvodina, Banaćani in Banat, Sandžaklije (Muslims in Serbia/Montenegro border), Kosovci in Kosovo, Crnogorci in Montenegro proper, Bokelji in southwest Montenegro, Trakiytci in Upper Thracian Lowlands, Dobrudzhantci in north-east Bulgarian region , Balkandzhiiin Central Balkan Mountains, Miziytci in north Bulgarian region, Pirintsi[91] in Blagoevgrad Province, Rupchi in the Rhodopes, etc.

Another interesting note is that the very term Slavic itself was registered in the US census of 2000 by more than 127,000 residents.

المصادر

- ^ Carl Skutsch (7 November 2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Routledge. pp. 974–. ISBN 978-1-135-19388-1.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmsu - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtheglobalist - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbbc - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةindependent - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnewadvent - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbarford - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBideleux - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSlav (people) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةprocopius - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةjordanes - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnationalism - ^ The Journal of Indo-European studies 1974, v.2

- ^ Etymology of the Polish-language word for Germany (Polish)

- ^ Xavier Delamarre (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Éditions Errance, p. 233.

- ^ John T. Koch (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, p. 1351.

- ^ Slav, on Oxford Dictionaries

- ^ F. Kluge, Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. 2002, siehe «Sklave»

- ^ Ф. М. Достоевский. Полное собрание сочинений: в 30-ти т. Т. 23. М., 1990, с. 63, 382.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlozinski - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbernstein - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةeuropean - ^ Florin Curta, Archeologické rozhledy LXI, 2009

- ^ Koleva, R. 1993: Slavic settlement on the territory of Bulgaria. In: J. Pavúk ed., Actes du XII-e Congre`s international des sciences préhistoriques et protohistoriques. Bratislava, 1–7 septembre 1991 IV, Bratislava,17–19.

- ^ Angelova, S. – Koleva, R. 2007: Archäologische Zeugnisse frühslawischer Besiedlung in Bulgarien. In: J. Henning ed., Post-Roman Towns, Trade, and Settlement in Europe and Byzantium, Berlin – New York, 481–508.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtruba - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةReferenceA - ^ Balabanov, Kosta (2011). Vinica Fortress: mythology, religion and history written with clay. Skopje: Matica. pp. 273–309.

- ^ Coon, Carleton S. (1939) The Peoples of Europe. Chapter VI, Sec. 7 New York: Macmillan Publishers.

- ^ Tacitus. Germania, page 46.

- ^ Curta 2001: 38. Dzino 2010: 95.

- ^ Barford, Paul M (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3977-3.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةufl - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةjordanes1 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةstrategikon - ^ Curta 2001, pp. 91–92, 315.

- ^ Stergar, Rok (12 July 2017). "Panslavism". International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- ^ Stergar, Rok. "Nationalities (Austria-Hungary)". International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- ^ Fritz, Stephen G. (2011). Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. University Press of Kentucky. Generalplan Ost (General plan for the east). ISBN 978-0-8131-4050-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mark Harrison (2002). "Accounting for War: Soviet Production, Employment, and the Defence Burden, 1940–1945". Cambridge University Press. p.167. ISBN 0-521-89424-7

- ^ Stephen J. Lee (2000). "European dictatorships, 1918–1945". Routledge. p.86. ISBN 0-415-23046-2.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan Offers an Unlikely Window Into Slavic Culture". The Moscow Times. 10 December 2013.

- ^ Russians left behind in Central Asia, by Robert Greenall, BBC News, 23 November 2005.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةkortlandt - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةkortlandt5 - ^ J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (2006), pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Russian". University of Toronto. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

Russian is the most widespread of the Slavic languages and the largest native language in Europe.

- ^ Kobyliński, Zbigniew (1995). "The Slavs". In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, c.500-c.700. Cambridge University Press. p. 531. ISBN 978-0-521-36291-7.

- ^ Roman Smal Stocki (1950). Slavs and Teutons: The Oldest Germanic-Slavic Relations. Bruce.

- ^ Raymond E. Zickel; Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1 December 1991). Soviet Union: A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-8444-0727-2.

- ^ Comparative Politics. Pearson Education India. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-81-317-6033-8.

- ^ Tarasov I.M. On the Mention of the Dnieper Varangians in the Context of the Legend of the Beginning of Kiev. 2023. P. 59–60

- ^ Vlasto 1970, p. 237.

- ^ أ ب Verbenko 2005, pp. 10–18.

- ^ Balanovsky 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Balanovsky 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Balanovsky & Rootsi 2008, pp. 236–250.

- ^ Balanovsky 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Rebała, K; Mikulich, AI; Tsybovsky, IS; Siváková, D; Dzupinková, Z; Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A; Szczerkowska, Z (2007). "Y-STR variation among Slavs: Evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (5): 406–14. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0125-6. PMID 17364156.

- ^ A. Zupan; et al. (2013). "The paternal perspective of the Slovenian population and its relationship with other populations". Annals of Human Biology. 40 (6): 515–526. doi:10.3109/03014460.2013.813584. PMID 23879710. S2CID 34621779.

However, a study by Battaglia et al. (2009) showed a variance peak for I2a1 in the Ukraine and, based on the observed pattern of variation, it could be suggested that at least part of the I2a1 haplogroup could have arrived in the Balkans and Slovenia with the Slavic migrations from a homeland in present-day Ukraine... The calculated age of this specific haplogroup together with the variation peak detected in the suggested Slavic homeland could represent a signal of Slavic migration arising from medieval Slavic expansions. However, the strong genetic barrier around the area of Bosnia and Herzegovina, associated with the high frequency of the I2a1b-M423 haplogroup, could also be a consequence of a Paleolithic genetic signal of a Balkan refuge area, followed by mixing with a medieval Slavic signal from modern-day Ukraine.

- ^ Underhill, Peter A. (2015), "The phylogenetic and geographic structure of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a", European Journal of Human Genetics 23 (1): 124–131, doi:, PMID 24667786, "R1a-M458 exceeds 20% in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Western Belarus. The lineage averages 11–15% across Russia and Ukraine and occurs at 7% or less elsewhere (Figure 2d). Unlike hg R1a-M458, the R1a-M558 clade is also common in the Volga-Uralic populations. R1a-M558 occurs at 10–33% in parts of Russia, exceeds 26% in Poland and Western Belarus, and varies between 10 and 23% in the Ukraine, whereas it drops 10-fold lower in Western Europe. In general, both R1a-M458 and R1a-M558 occur at low but informative frequencies in Balkan populations with known Slavonic heritage."

- ^ O.M. Utevska (2017). Генофонд українців за різними системами генетичних маркерів: походження і місце на європейському генетичному просторі [The gene pool of Ukrainians revealed by different systems of genetic markers: the origin and statement in Europe] (PhD) (in الأوكرانية). National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. pp. 219–226, 302.

- ^ Neparáczki, Endre; et al. (2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. Nature Research. 9 (16569): 16569. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916569N. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606.

Hg I2a1a2b-L621 was present in 5 Conqueror samples, and a 6th sample form Magyarhomorog (MH/9) most likely also belongs here, as MH/9 is a likely kin of MH/16 (see below). This Hg of European origin is most prominent in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, especially among Slavic speaking groups.

- ^ Pamjav, Horolma; Fehér, Tibor; Németh, Endre; Koppány Csáji, László (2019). Genetika és őstörténet (in الهنغارية). Napkút Kiadó. p. 58. ISBN 978-963-263-855-3.

Az I2-CTS10228 (köznevén "dinári-kárpáti") alcsoport legkorábbi közös őse 2200 évvel ezelőttre tehető, így esetében nem arról van szó, hogy a mezolit népesség Kelet-Európában ilyen mértékben fennmaradt volna, hanem arról, hogy egy, a mezolit csoportoktól származó szűk család az európai vaskorban sikeresen integrálódott egy olyan társadalomba, amely hamarosan erőteljes demográfiai expanzióba kezdett. Ez is mutatja, hogy nem feltétlenül népek, mintsem családok sikerével, nemzetségek elterjedésével is számolnunk kell, és ezt a jelenlegi etnikai identitással összefüggésbe hozni lehetetlen. A csoport elterjedése alapján valószínűsíthető, hogy a szláv népek migrációjában vett részt, így válva az R1a-t követően a második legdominánsabb csoporttá a mai Kelet-Európában. Nyugat-Európából viszont teljes mértékben hiányzik, kivéve a kora középkorban szláv nyelvet beszélő keletnémet területeket.

- ^ Fóthi, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Fehér, T. (2020), "Genetic analysis of male Hungarian Conquerors: European and Asian paternal lineages of the conquering Hungarian tribes", Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 12 (1): 31, doi:, Bibcode: 2020ArAnS..12...31F, "Based on SNP analysis, the CTS10228 group is 2200 ± 300 years old. The group's demographic expansion may have begun in Southeast Poland around that time, as carriers of the oldest subgroup are found there today. The group cannot solely be tied to the Slavs, because the proto-Slavic period was later, around 300–500 CE... The SNP-based age of the Eastern European CTS10228 branch is 2200 ± 300 years old. The carriers of the most ancient subgroup live in Southeast Poland, and it is likely that the rapid demographic expansion which brought the marker to other regions in Europe began there. The largest demographic explosion occurred in the Balkans, where the subgroup is dominant in 50.5% of Croatians, 30.1% of Serbs, 31.4% of Montenegrins, and in about 20% of Albanians and Greeks. As a result, this subgroup is often called Dinaric. It is interesting that while it is dominant among modern Balkan peoples, this subgroup has not been present yet during the Roman period, as it is almost absent in Italy as well (see Online Resource 5; ESM_5)."

- ^ Kushniarevich, Alena; Kassian, Alexei (2020), "Genetics and Slavic languages", in Marc L. Greenberg, Encyclopedia of Slavic Languages and Linguistics Online, Brill, doi:, "The geographic distributions of the major eastern European NRY haplogroups (R1a-Z282, I2a-P37) overlap with the area occupied by the present-day Slavs to a great extent, and it might be tempting to consider both haplogroups as Slavic-specic patrilineal lineages"

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (1989). Religion and Nationalism in Soviet and East European Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 380–. ISBN 978-0-8223-0891-1.

- ^ Goldblatt, Harvey (December 1986). "Orthodox Slavic Heritage and National Consciousness: Aspects of the East Slavic and South Slavic National Revivals". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. 10 (3/4): 336–354. JSTOR 41036261.

- ^ Zdravkovski, Aleksander; Morrison, Kenneth (January 2014). "The Orthodox Churches of Macedonia and Montenegro: The Quest for Autocephaly". Religion and Politics in Post-Socialist Central and Southeastern Europe. pp. 240–262. doi:10.1057/9781137330727_10. ISBN 978-1-349-46120-2.

- ^ Sparrow, Thomas (16 June 2021). "Sorbs: The ethnic minority inside Germany". BBC. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Vučković, Marija (2008). "Savremena istraživanja malih etničkih zajednica" [Contemporary studies of small ethnic communities]. XXI Vek (in صربية-كرواتية). 3: 2–8. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ Lopasic, Alexander (1981). "Bosnian Muslims: A Search for Identity". British Society for Middle Eastern Studies. Taylor & Francis. 8 (2): 115–121. doi:10.1080/13530198108705319. JSTOR 194542.

- ^ Hugh Poulton; Suha Taji-Farouki (January 1997). Muslim Identity and the Balkan State. Hurst. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-85065-276-2.

- ^ Bursać, Milan, ed. (2000), ГОРАНЦИ, МУСЛИМАНИ И ТУРЦИ У ШАРПЛАНИНСКИМ ЖУПАМА СРБИЈЕ: ПРОБЛЕМИ САДАШЊИХ УСЛОВА ЖИВОТА И ОПСТАНКА: Зборник радова са "Округлог стола" одржаног 19. априла 2000. године у Српској академији наука и уметности, Belgrade: SANU, pp. 71=73, http://www.rastko.rs/rastko-gora/zbornici/gora2000.php

- ^ Kowan, J. (2000). Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference. London: Pluto Press. p. 111. ISBN 0-7453-1594-1.

- ^ Tarasov I.M. On the Mention of the Dnieper Varangians in the Context of the Legend of the Beginning of Kiev. 2023. P. 59–60

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond, ISBN 0-521-22717-8, 1992, page 600: "In the place of the vanished Treres and Tilataei we find the Serdi for whom there is no evidence before the first century BC. It has for long being supposed on convincing linguistic and archeological grounds that this tribe was of Celtic origin."

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Florin Curta's An ironic smile: the Carpathian Mountains and the migration of the Slavs, Studia mediaevalia Europaea et orientalia. Miscellanea in honorem professoris emeriti Victor Spinei oblata, edited by George Bilavschi and Dan Aparaschivei, 47–72. Bucharest: Editura Academiei Române, 2018.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 35.

- ^ Simmonds, Lauren (May 11, 2023). "Croatian Language – The Difference between Dalmatic and Dalmatian".

- ^ Balanovsky & Rootsi 2008, pp. 236—250.

- ^ Klyuchevsky, Vasily (1987). "1: Mysl". The course of the Russian history (in الروسية). ISBN 5-244-00072-1. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Lewis (1994). "ch 1". Archived from the original on 1 April 2001.

- ^ Eigeland, Tor. 1976. "The golden caliphate". Saudi Aramco World, September/October 1976, pp. 12–16.

- ^ "Wend". Britannica.com. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2008-05-07. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ "Polabian language". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ "Contemporary paternal genetic landscape of Polish and German populations: from early medieval Slavic expansion to post-World War II resettlements". European Journal of Human Genetics. 21 (4): 415–22. 2013. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.190. PMC 3598329. PMID 22968131.

- ^ "Y-chromosomal STR haplotype analysis reveals surname-associated strata in the East-German population". European Journal of Human Genetics. 14 (5): 577–582. 2006. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201572. PMID 16435000.

- ^ Nandriș, Grigore (June 1956). "The Relations between Toponymy and Ethnology in Rumania". The Slavonic and East European Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 34 (83): 490–494. JSTOR 4204755.

- ^ Performing Democracy: Bulgarian Music and Musicians in Transition Page 11 By Donna Anne Buchanan ISBN 0226078264

طالع أيضاً

|

وصلات خارجية

| Slavs

]].- Lozinski, B. Philip (1964, 2004), "The Name SLAV", in Ferguson, Alan D.; Levin, Alfred, Essays in Russian History, A collection dedicated to George Vernadsky, Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, Vassil Karloukovski, pp. 19-30.

- Kortlandt, Frederik. "FROM PROTO-INDO-EUROPEAN TO SLAVIC" (pdf). Frederik Kortlandt. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- THE ORIGIN OF THE BALTIC, GERMAN AND SLAVIC PEOPLE. THE ICELAND AGES

- "Najstariji period istorije Slovena (Venedi, Sloveni i Anti)" - N. S. Deržavin

- SLOVENI: UNDE ORTI ESTIS? SLOVÁCI, KDE SÚ VAŠE KORENE?, by Cyril A. Hromník (mainly in Slova).

- Site about Slavics, Slavic Countries, Cultures, Languages, etc (mainly in Russian)

- The early wars between the Macedonian Slavs and the Byzantines (from medieval sources)

- "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective"

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/The Slavs "|The Slavs]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

[[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/The Slavs "|The Slavs]"]. Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Check|url=value (help)

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>

- CS1 الأوكرانية-language sources (uk)

- CS1 الهنغارية-language sources (hu)

- CS1 صربية-كرواتية-language sources (sh)

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- "Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

- Articles using infobox ethnic group with image parameters

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2010

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2015

- CS1 errors: URL

- سلاڤ

- جماعات عرقية سلاڤية

- جماعات عرقية في أوروپا