سلاڤونية الكنيسة القديمة

| Old Church Slavonic | |

|---|---|

| Old Church Slavic | |

| ⱄⰾⱁⰲⱑⱀⱐⱄⰽⱏ ⱗⰸⱏⰺⰽⱏ словѣ́ньскъ ѩзꙑ́къ | |

| |

| موطنها | Formerly in Slavic areas under the influence of Byzantium (both Catholic and Orthodox) |

| المنطقة | |

| الحقبة | 9th–11th centuries; then evolved into several variants of Church Slavonic including Middle Bulgarian |

الهندو-اوروپية

| |

| Glagolitic, Cyrillic | |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | chu |

| ISO 639-2 | chu |

| ISO 639-3 | chu (includes Church Slavonic) |

| Glottolog | chur1257 Church Slavic |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-a |

Old Church Slavonic[1] or Old Slavonic (/sləˈvɒnɪk, slæˈ-/)[أ] is the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and undertaking the task of translating the Gospels and necessary liturgical books into it[9] as part of the Christianization of the Slavs.[10][11] It is thought to have been based primarily on the dialect of the 9th-century Byzantine Slavs living in the Province of Thessalonica (in present-day Greece).

Old Church Slavonic played an important role in the history of the Slavic languages and served as a basis and model for later Church Slavonic traditions, and some Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches use this later Church Slavonic as a liturgical language to this day.

As the oldest attested Slavic language, OCS provides important evidence for the features of Proto-Slavic, the reconstructed common ancestor of all Slavic languages.

Nomenclature

The name of the language in Old Church Slavonic texts was simply Slavic (словѣ́ньскъ ѩꙁꙑ́къ, slověnĭskŭ językŭ),[12] derived from the word for Slavs (словѣ́нє, slověne), the self-designation of the compilers of the texts. This name is preserved in the modern native names of the Slovak and Slovene languages. The language is sometimes called Old Slavic, which may be confused with the distinct Proto-Slavic language. Different strains of nationalists have tried to 'claim' Old Church Slavonic; thus OCS has also been variously called Old Bulgarian, Old Croatian, Old Macedonian or Old Serbian, or even Old Slovak, Old Slovenian.[13] The commonly accepted terms in modern English-language Slavic studies are Old Church Slavonic and Old Church Slavic.

The term Old Bulgarian[14] (بالبلغارية: старобългарски, ألمانية: Altbulgarisch) is the only designation used by Bulgarian-language writers. It was used in numerous 19th-century sources, e.g. by August Schleicher, Martin Hattala, Leopold Geitler and August Leskien,[15][16][17] who noted similarities between the first literary Slavic works and the modern Bulgarian language. For similar reasons, Russian linguist Aleksandr Vostokov used the term Slav-Bulgarian. The term is still used by some writers but nowadays normally avoided in favor of Old Church Slavonic.

The term Old Macedonian[18][19][20][21][22][23][24] is occasionally used by Western scholars in a regional context.

The obsolete[25] term Old Slovenian[25][26][27][28] was used by early 19th-century scholars who conjectured that the language was based on the dialect of Pannonia.

التاريخ

It is generally held that the language was standardized by two Byzantine missionaries, Cyril and his brother Methodius, for a mission to Great Moravia (the territory of today's eastern Czechia and western Slovakia; for details, see Glagolitic alphabet).[29] The mission took place in response to a request by Great Moravia's ruler, Duke Rastislav for the development of Slavonic liturgy.[30]

As part of preparations for the mission, in 862/863, the missionaries developed the Glagolitic alphabet and translated the most important prayers and liturgical books, including the Aprakos Evangeliar, the Psalter, and the Acts of the Apostles, allegedly basing the language on the Slavic dialect spoken in the hinterland of their hometown, Thessaloniki,[ب] in present-day Greece.

Based on a number of archaicisms preserved until the early 20th century (the articulation of yat as /æ/ in Boboshticë, Drenovë, around Thessaloniki, Razlog, the Rhodopes and Thrace and of yery as /ɨ/ around Castoria and the Rhodopes, the presence of decomposed nasalisms around Castoria and Thessaloniki, etc.), the dialect is posited to have been part of a macrodialect extending from the Adriatic to the Black sea, and covering southern Albania, northern Greece and the southernmost parts of Bulgaria.[32]

Because of the very short time between Rastislav's request and the actual mission, it has been widely suggested that both the Glagolitic alphabet and the translations had been "in the works" for some time, probably for a planned mission to the Bulgar state.[33][34][35]

The language and the Glagolitic alphabet, as taught at the Great Moravian Academy (سلوڤاكية: Veľkomoravské učilište), were used for government and religious documents and books in Great Moravia between 863 and 885. The texts written during this phase contain characteristics of the West Slavic vernaculars in Great Moravia.

In 885 Pope Stephen V prohibited the use of Old Church Slavonic in Great Moravia in favour of Latin.[36] King Svatopluk I of Great Moravia expelled the Byzantine missionary contingent in 886.

Exiled students of the two apostles then brought the Glagolitic alphabet to the Bulgarian Empire. Boris I of Bulgaria (ح. 852–889) received and officially accepted them; he established the Preslav Literary School and the Ohrid Literary School.[37][38][39] Both schools originally used the Glagolitic alphabet, though the Cyrillic script developed early on at the Preslav Literary School, where it superseded Glagolitic as official in Bulgaria in 893.[40][41][42][43]

The texts written during this era exhibit certain linguistic features of the vernaculars of the First Bulgarian Empire. Old Church Slavonic spread to other South-Eastern, Central, and Eastern European Slavic territories, most notably Croatia, Serbia, Bohemia, Lesser Poland, and principalities of the Kievan Rus' – while retaining characteristically Eastern South Slavic linguistic features.

Later texts written in each of those territories began to take on characteristics of the local Slavic vernaculars, and by the mid-11th century Old Church Slavonic had diversified into a number of regional varieties (known as recensions). These local varieties are collectively known as the Church Slavonic language.[44]

Apart from use in the Slavic countries, Old Church Slavonic served as a liturgical language in the Romanian Orthodox Church, and also as a literary and official language of the princedoms of Wallachia and Moldavia (see Old Church Slavonic in Romania), before gradually being replaced by Romanian during the 16th to 17th centuries.

Church Slavonic maintained a prestigious status, particularly in Russia, for many centuries – among Slavs in the East it had a status analogous to that of Latin in Western Europe, but had the advantage of being substantially less divergent from the vernacular tongues of average parishioners.

Some Orthodox churches, such as the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox Church, Ukrainian Orthodox Church and Macedonian Orthodox Church – Ohrid Archbishopric, as well as several Eastern Catholic Churches[which?], still use Church Slavonic in their services and chants as of 2021.[46]

Scripts

Initially Old Church Slavonic was written with the Glagolitic alphabet, but later Glagolitic was replaced by Cyrillic,[47] which was developed in the First Bulgarian Empire by a decree of Boris I of Bulgaria in the 9th century. Of the Old Church Slavonic canon, about two-thirds is written in Glagolitic.

The local Bosnian Cyrillic alphabet, known as Bosančica, was preserved in Bosnia and parts of Croatia, while a variant of the angular Glagolitic alphabet was preserved in Croatia. See Early Cyrillic alphabet for a detailed description of the script and information about the sounds it originally expressed.

Phonology

For Old Church Slavonic, the following segments are reconstructible.[48] A few sounds are given in Slavic transliterated form rather than in IPA, as the exact realisation is uncertain and often differs depending on the area that a text originated from.

Consonants

For English equivalents and narrow transcriptions of sounds, see Old Church Slavonic Pronunciation on Wiktionary.

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ[1] | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t'[2] | k |

| voiced | b | d | d'[3] | ɡ | |

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | t͡ʃ | ||

| voiced | d͡z[4] | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s | ʃ | x | |

| voiced | z | ʒ | |||

| Lateral | l | lʲ[5] | |||

| Trill | r | rʲ[6] | |||

| Approximant | v | j | |||

- ^a These phonemes were written and articulated differently in different recensions: as ⟨Ⱌ⟩ (/t͡s/) and ⟨Ⰷ⟩ (/d͡z/) in the Moravian recension, ⟨Ⱌ⟩ (/t͡s/) and ⟨Ⰸ⟩ (/z/) in the Bohemian recension, ⟨Ⱋ⟩/⟨щ⟩ ([ʃt]) and ⟨ⰆⰄ⟩/⟨жд⟩ ([ʒd]) in the Bulgarian recension(s). In Serbia, ⟨Ꙉ⟩ was used to denote both sounds. The abundance of Middle Ages toponyms featuring [ʃt] and [ʒd] in North Macedonia, Kosovo and the Torlak-speaking parts of Serbia indicates that at the time, the clusters were articulated as [ʃt] & [ʒd] as well, even though current reflexes are different.[49]

- ^b /dz/ appears mostly in early texts, becoming /z/ later on.

- ^c The distinction between /l/, /n/ and /r/, on one hand, and palatal /lʲ/, /nʲ/ and /rʲ/, on the other, is not always indicated in writing. When it is, it is shown by a palatization diacritic over the letter: ⟨ л҄ ⟩ ⟨ н҄ ⟩ ⟨ р҄ ⟩.

Vowels

For English equivalents and narrow transcriptions of sounds, see Old Church Slavonic Pronunciation on Wiktionary.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Accent is not indicated in writing and must be inferred from later languages and from reconstructions of Proto-Slavic.

- ^a All front vowels were iotated word-initially and succeeding other vowels. The same sometimes applied for *a and *ǫ. In the Bulgarian region, an epinthetic *v was inserted before *ǫ in the place of iotation.

- ^b The distinction between /i/, /ji/ and /jɪ/ is rarely indicated in writing and must be inferred from reconstructions of Proto-Slavic. In Glagolitic, the three are written as <ⰻ>, <ⰹ>, and <ⰺ> respectively. In Cyrillic, /jɪ/ may sometimes be written as ı, and /ji/ as ї, although this is rarely the case.

- ^c Yers preceding *j became tense, this was inconsistently reflected in writing in the case of *ь (ex: чаꙗньѥ or чаꙗние, both pronounced [t͡ʃɑjɑn̪ije]), but never with *ъ (which was always written as a yery).

- ^d Yery was the descendant of Proto-Blato-Slavic long *ū and was a high back unrounded vowel. Tense *ъ merged with *y, which gave rise to yery's spelling as <ъи> (later <ꙑ>, modern <ы>).

- ^e The yer vowels ь and ъ (ĭ and ŭ) are often called "ultrashort" and were lower, more centralised and shorter than their tense counterparts *i and *y. Both yers had a strong and a weak variant, with a yer always being strong if the next vowel is another yer. Weak yers disappeared in most positions in the word, already sporadically in the earliest texts but more frequently later on. Strong yers, on the other hand, merged with other vowels, particularly ĭ with e and ŭ with o, but differently in different areas.

- ^f The pronunciation of yat (ѣ/ě) differed by area. In Bulgaria it was a relatively open vowel, commonly reconstructed as /æ/, but further north its pronunciation was more closed and it eventually became a diphthong /je/ (e.g. in modern standard Bosnian, Croatian and Montenegrin, or modern standard Serbian spoken in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as in Czech — the source of the grapheme ě) or even /i/ in many areas (e.g. in Chakavian Croatian, Shtokavian Ikavian Croatian and Bosnian dialects or Ukrainian) or /e/ (modern standard Serbian spoken in Serbia).

- ^g *a was the descendant of Proto-Slavic long *o and was a low back unrounded vowel. Its iotated variant was often confused with *ě (in Glagolitic they are even the same letter: Ⱑ), so *a was probably fronted to *ě when it followed palatal consonants (this is still the case in Rhodopean dialects).

- ^h The exact articulation of the nasal vowels is unclear because different areas tend to merge them with different vowels. ę /ɛ̃/ is occasionally seen to merge with e or ě in South Slavic, but becomes ja early on in East Slavic. ǫ /ɔ̃/ generally merges with u or o, but in Bulgaria, ǫ was apparently unrounded and eventually merged with ъ.

Phonotactics

Several notable constraints on the distribution of the phonemes can be identified, mostly resulting from the tendencies occurring within the Common Slavic period, such as intrasyllabic synharmony and the law of open syllables. For consonant and vowel clusters and sequences of a consonant and a vowel, the following constraints can be ascertained:[50]

- Two adjacent consonants tend not to share identical features of manner of articulation

- No syllable ends in a consonant

- Every obstruent agrees in voicing with the following obstruent

- Velars do not occur before front vowels

- Phonetically palatalized consonants do not occur before certain back vowels

- The back vowels /y/ and /ъ/ as well as front vowels other than /i/ do not occur word-initially: the two back vowels take prothetic /v/ and the front vowels prothetic /j/. Initial /a/ may take either prothetic consonant or none at all.

- Vowel sequences are attested in only one lexeme (paǫčina 'spider's web') and in the suffixes /aa/ and /ěa/ of the imperfect

- At morpheme boundaries, the following vowel sequences occur: /ai/, /au/, /ao/, /oi/, /ou/, /oo/, /ěi/, /ěo/

Morphophonemic alternations

As a result of the first and the second Slavic palatalizations, velars alternate with dentals and palatals. In addition, as a result of a process usually termed iotation (or iodization), velars and dentals alternate with palatals in various inflected forms and in word formation.

| original | /k/ | /g/ | /x/ | /sk/ | /zg/ | /sx/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| first palatalization and iotation | /č/ | /ž/ | /š/ | /št/ | /žd/ | /š/ |

| second palatalization | /c/ | /dz/ | /s/ | /sc/, /st/ | /zd/ | /sc/ |

| original | /b/ | /p/ | /sp/ | /d/ | /zd/ | /t/ | /st/ | /z/ | /s/ | /l/ | /sl/ | /m/ | /n/ | /sn/ | /zn/ | /r/ | /tr/ | /dr/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iotation | /bl'/ | /pl'/ | /žd/ | /žd/ | /št/ | /št/ | /ž/ | /š/ | /l'/ | /šl'/ | /ml'/ | /n'/ | /šn'/ | /žn'/ | /r'/ | /štr'/ | /ždr'/ |

In some forms the alternations of /c/ with /č/ and of /dz/ with /ž/ occur, in which the corresponding velar is missing. The dental alternants of velars occur regularly before /ě/ and /i/ in the declension and in the imperative, and somewhat less regularly in various forms after /i/, /ę/, /ь/ and /rь/.[51] The palatal alternants of velars occur before front vowels in all other environments, where dental alternants do not occur, as well as in various places in inflection and word formation described below.[52]

As a result of earlier alternations between short and long vowels in roots in Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Balto-Slavic and Proto-Slavic times, and of the fronting of vowels after palatalized consonants, the following vowel alternations are attested in OCS: /ь/ : /i/; /ъ/ : /y/ : /u/; /e/ : /ě/ : /i/; /o/ : /a/; /o/ : /e/; /ě/ : /a/; /ъ/ : /ь/; /y/ : /i/; /ě/ : /i/; /y/ : /ę/.[52]

Vowel:∅ alternations sometimes occurred as a result of sporadic loss of weak yer, which later occurred in almost all Slavic dialects. The phonetic value of the corresponding vocalized strong jer is dialect-specific.

Grammar

As an ancient Indo-European language, OCS has a highly inflective morphology. Inflected forms are divided in two groups, nominals and verbs. Nominals are further divided into nouns, adjectives and pronouns. Numerals inflect either as nouns or pronouns, with 1–4 showing gender agreement as well.

Nominals can be declined in three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), three numbers (singular, plural, dual) and seven cases: nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, genitive, and locative. There are five basic inflectional classes for nouns: o/jo-stems, a/ja-stems, i-stems, u-stems and consonant stems. Forms throughout the inflectional paradigm usually exhibit morphophonemic alternations.

Fronting of vowels after palatals and j yielded dual inflectional class o : jo and a : ja, whereas palatalizations affected stem as a synchronic process (N sg. vlьkъ, V sg. vlьče; L sg. vlьcě). Productive classes are o/jo-, a/ja- and i-stems. Sample paradigms are given in the table below:

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Stem type | Nom | Voc | Acc | Gen | Loc | Dat | Instr | Nom/Voc/Acc | Gen/Loc | Dat/Instr | Nom/Voc | Acc | Gen | Loc | Dat | Instr |

| "city" | o m. | gradъ | grade | gradъ | grada | gradě | gradu | gradomь | grada | gradu | gradoma | gradi | grady | gradъ | graděxъ | gradomъ | grady |

| "knife" | jo m. | nožь | nožu | nožь | noža | noži | nožu | nožemь | noža | nožu | nožema | noži | nožę | nožь | nožixъ | nožemъ | noži |

| "wolf" | o m | vlьkъ | vlьče | vlьkъ | vlьka | vlьcě | vlьku | vlьkomь | vlьka | vlьku | vlьkoma | vlьci | vlьky | vlьkъ | vlьcěxъ | vlьkomъ | vlьky |

| "wine" | o n. | vino | vino | vino | vina | vině | vinu | vinomь | vině | vinu | vinoma | vina | vina | vinъ | viněxъ | vinomъ | viny |

| "field" | jo n. | polje | polje | polje | polja | polji | polju | poljemь | polji | polju | poljema | polja | polja | poljь | poljixъ | poljemъ | polji |

| "woman" | a f. | žena | ženo | ženǫ | ženy | ženě | ženě | ženojǫ | ženě | ženu | ženama | ženy | ženy | ženъ | ženaxъ | ženamъ | ženami |

| "soul" | ja f. | duša | duše | dušǫ | dušę | duši | duši | dušejǫ | duši | dušu | dušama | dušę | dušę | dušь | dušaxъ | dušamъ | dušami |

| "hand" | a f. | rǫka | rǫko | rǫkǫ | rǫky | rǫcě | rǫcě | rǫkojǫ | rǫcě | rǫku | rǫkama | rǫky | rǫky | rǫkъ | rǫkaxъ | rǫkamъ | rǫkami |

| "bone" | i f. | kostь | kosti | kostь | kosti | kosti | kosti | kostьjǫ | kosti | kostьju | kostьma | kosti | kosti | kostьjь | kostьxъ | kostьmъ | kostьmi |

| "home" | u m. | domъ | domu | domъ/-a | domu | domu | domovi | domъmь | domy | domovu | domъma | domove | domy | domovъ | domъxъ | domъmъ | domъmi |

Adjectives are inflected as o/jo-stems (masculine and neuter) and a/ja-stems (feminine), in three genders. They could have short (indefinite) or long (definite) variants, the latter being formed by suffixing to the indefinite form the anaphoric third-person pronoun jь.

Synthetic verbal conjugation is expressed in present, aorist and imperfect tenses while perfect, pluperfect, future and conditional tenses/moods are made by combining auxiliary verbs with participles or synthetic tense forms. Sample conjugation for the verb vesti "to lead" (underlyingly ved-ti) is given in the table below.

| person/number | Present | Asigmatic (simple, root) aorist | Sigmatic (s-) aorist | New (ox) aorist | Imperfect | Imperative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 sg. | vedǫ | vedъ | věsъ | vedoxъ | veděaxъ | |

| 2 sg. | vedeši | vede | vede | vede | veděaše | vedi |

| 3 sg. | vedetъ | vede | vede | vede | veděaše | vedi |

| 1 dual | vedevě | vedově | věsově | vedoxově | veděaxově | veděvě |

| 2 dual | vedeta | vedeta | věsta | vedosta | veděašeta | veděta |

| 3 dual | vedete | vedete | věste | vedoste | veděašete | |

| 1 plural | vedemъ | vedomъ | věsomъ | vedoxomъ | veděaxomъ | veděmъ |

| 2 plural | vedete | vedete | věste | vedoste | veděašete | veděte |

| 3 plural | vedǫtъ | vedǫ | věsę | vedošę | veděaxǫ |

Basis

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الكنيسة الأرثوذكسية الشرقية |

|---|

| استعراض |

Written evidence of Old Church Slavonic survives in a relatively small body of manuscripts, most of them written in the First Bulgarian Empire during the late 10th and the early 11th centuries. The language has an Eastern South Slavic basis in the Bulgarian-Macedonian dialectal area, with an admixture of Western Slavic (Moravian) features inherited during the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia (863–885).[53]

The only well-preserved manuscript of the Moravian recension, the Kiev Missal, or the Kiev Folia, is characterised by the replacement of some South Slavic phonetic and lexical features with Western Slavic ones. Manuscripts written in the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396) have, on the other hand, few Western Slavic features.

Though South Slavic in phonology and morphology, Old Church Slavonic was influenced by Byzantine Greek in syntax and style, and is characterized by complex subordinate sentence structures and participial constructions.[53]

A large body of complex, polymorphemic words was coined, first by Saint Cyril himself and then by his students at the academies in Great Moravia and the First Bulgarian Empire, to denote complex abstract and religious terms, e.g., ꙁълодѣꙗньѥ (zъlodějanьje) from ꙁъло ('evil') + дѣти ('do') + ньѥ (noun suffix), i.e., 'evil deed'. A significant part of them wере calqued directly from Greek.[53]

Old Church Slavonic is valuable to historical linguists since it preserves archaic features believed to have once been common to all Slavic languages such as:

- Most significantly, the yer (extra-short) vowels: /ɪ̆/ and /ʊ̆/

- Nasal vowels: /ɛ̃/ and /ɔ̃/

- Near-open articulation of the yat vowel (/æ/)

- Palatal consonants /ɲ/ and /ʎ/ from Proto-Slavic *ň and *ľ

- Proto-Slavic declension system based on stem endings, including those that later disappeared in attested languages (such as u-stems)

- Dual as a distinct grammatical number from singular and plural

- Aorist, imperfect, Proto-Slavic paradigms for participles

Old Church Slavonic is also likely to have preserved an extremely archaic type of accentuation (probably[بحاجة لمصدر] close to the Chakavian dialect of modern Serbo-Croatian), but unfortunately, no accent marks appear in the written manuscripts.

The South Slavic and Eastern South Slavic nature of the language is evident from the following variations:

- Phonetic:

- ra, la by means of liquid metathesis of Proto-Slavic *or, *ol clusters

- sě from Proto-Slavic *xě < *xai

- cv, (d)zv from Proto-Slavic *kvě, *gvě < *kvai, *gvai

- Morphological:

- Morphosyntactic use of the dative possessive case in personal pronouns and nouns: братъ ми (bratŭ mi, "my brother"), рѫка ти (rǫka ti, "your hand"), отъпоущенье грѣхомъ (otŭpuštenĭje grěxomŭ, "remission of sins"), храмъ молитвѣ (xramŭ molitvě, 'house of prayer'), etc.

- periphrastic future tense using the verb хотѣти (xotěti, "to want"), for example, хоштѫ писати (xoštǫ pisati, "I will write")

- Use of the comparative form мьнии (mĭniji, "smaller") to denote "younger"

- Morphosyntactic use of suffixed demonstrative pronouns тъ, та, то (tъ, ta, to). In Bulgarian and Macedonian, these developed into suffixed definite articles and also took the place of the third person singular and plural pronouns онъ, она, оно, они (onъ, ona, ono, oni) > той/тоj, тя/таа, то/тоа, те/тие ('he, she, it, they')

Old Church Slavonic also shares the following phonetic features only with Bulgarian:

- Near-open articulation *æ / *jæ of the Yat vowel (ě); still preserved in the Bulgarian dialects of the Rhodope mountains, the Razlog dialect, the Shumen dialect and partially preserved as *ja (ʲa) across Yakavian Eastern Bulgarian

- /ʃt/ and /ʒd/ as reflexes of Proto-Slavic *ťʲ (< *tj and *gt, *kt) and *ďʲ (< *dj).

| Proto-Slavic | Old Church Slavonic | Bulgarian | Macedonian | Serbo-Croatian | Slovenian | Slovak | Czech | Polish | Russian[22] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *dʲ medja ('boundary') |

жд ([ʒd]) |

жд ([ʒd]) |

ѓ (/ʄ/) |

ђ (/d͡ʑ/) |

j (/j/) |

dz (/d͡z/) |

z (/z/) |

dz (/d͡z/) |

ж (/ʐ/)

|

межда |

межда |

меѓа |

међа |

meja |

medza |

meza |

miedza |

межа

| |

| *tʲ světja ('candle') |

щ ([ʃt]) |

щ ([ʃt]) |

ќ (/c/) |

ћ (/t͡ɕ/) |

č (/t͡ʃ/) |

c (/t͡s/) |

c (/t͡s/) |

c (/t͡s/) |

ч (/t͡ɕ/)

|

свѣща |

свещ |

свеќа |

свећа |

sveča |

svieca |

svíce |

świeca |

свеча

|

Local influences (recensions)

Over time, the language adopted more and more features from local Slavic vernaculars, producing different variants referred to as Recensions. Modern convention differentiates between the earliest, classical form of the language, referred to as Old Church Slavonic, and later, vernacular-coloured forms, collectively designated as Church Slavonic.[57] More specifically, Old Church Slavonic is exemplified by extant manuscripts written between the 9th and 11th century in Great Moravia and the First Bulgarian Empire.

Great Moravia

The language was standardized for the first time by the mission of the two apostles to Great Moravia from 863. The manuscripts of the Moravian recension are therefore the earliest dated of the OCS recensions.[58] The recension takes its name from the Slavic state of Great Moravia which existed in Central Europe during the 9th century on the territory of today's Czechia, Slovakia, northern Austria and southeastern Poland.

Moravian recension

This recension is exemplified by the Kiev Missal. Its linguistic characteristics include:

- Confusion between the letters Big yus ⟨Ѫѫ⟩ and Uk ⟨Ѹѹ⟩ – this occurs once in the Kiev Folia, when the expected form въсоудъ vъsudъ is spelled въсѫдъ vъsǫdъ

- /ts/ from Proto-Slavic *tj, use of /dz/ from *dj, /ʃtʃ/ *skj

- Use of the words mьša, cirky, papežь, prěfacija, klepati, piskati etc.

- Preservation of the consonant cluster /dl/ (e.g. modlitvami)

- Use of the ending –ъmь instead of –omь in the masculine singular instrumental, use of the pronoun čьso

Bohemian recension

The Bohemian recension is derived from the Moravian recension and was used until 1097. It was written in Glagolitic, which is posited to have been carried over to the Czech lands even before the death of Methodius.[59] It is preserved in religious texts (e.g. Prague Fragments), legends and glosses and shows substantial influence of the Western Slavic vernacular in Bohemia at the time. Its main features are:[60]

- PSl. *tj, *kt(i), *dj, *gt(i) → c /ts/, z: pomocь, utvrьzenie

- PSl. *stj, *skj → šč: *očistjenьje → očiščenie

- ending -ъmь in instr. sg. (instead of -omь): obrazъmь

- verbs with prefix vy- (instead of iz-)

- promoting of etymological -dl-, -tl- (světidlъna, vъsedli, inconsistently)

- suppressing of epenthetic l (prěstavenie, inconsistently)

- -š- in original stem vьx- (všěx) after 3rd palatalization

- development of yers and nasals coincident with development in Czech lands

- fully syllabic r and l

- ending -my in first-person pl. verbs

- missing terminal -tь in third-person present tense indicative

- creating future tense using prefix po-

- using words prosba (request), zagrada (garden), požadati (to ask for), potrěbovati (to need), conjunctions aby, nebo etc.

First Bulgarian Empire

Although the missionary work of Constantine and Methodius took place in Great Moravia, it was in the First Bulgarian Empire that early Slavic written culture and liturgical literature really flourished.[61] The Old Church Slavonic language was adopted as state and liturgical language in 893, and was taught and refined further in two bespoke academies created in Preslav (Bulgarian capital between 893 and 972), and Ohrid (Bulgarian capital between 991/997 and 1015).[62][63][64]

The language did not represent one regional dialect but a generalized form of early eastern South Slavic, which cannot be localized.[65] The existence of two major literary centres in the Empire led in the period from the 9th to the 11th centuries to the emergence of two recensions (otherwise called "redactions"), termed "Eastern" and "Western" respectively.[66][67]

Some researchers do not differentiate between manuscripts of the two recensions, preferring to group them together in a "Macedo-Bulgarian"[68] or simply "Bulgarian" recension.[61][69][17] The development of Old Church Slavonic literacy had the effect of preventing the assimilation of the South Slavs into neighboring cultures, which promoted the formation of a distinct Bulgarian identity.[70]

Common features of both recensions:

- Consistent use of the soft consonant clusters ⟨щ⟩ (*ʃt) & ⟨жд⟩ (*ʒd) for Pra-Slavic *tj/*gt/*kt and *dj. Articulation as *c & *ɟ in a number of Macedonian dialects is a later development due to Serbian influence in the Late Middle Ages, aided by Late Middle Bulgarian's mutation of palatal *t & *d > palatal k & g[71][72][73]

- Consistent use of the yat vowel (ě)

- Inconsistent use of the epenthetic l, with attested forms both with and without it: korabĺь & korabъ, zemĺě & zemьja, the latter possibly indicating a shift from <ĺ> to <j>.[74][75] Modern Bulgarian/Macedonian lack epenthetic l

- Replacement of the affricate ⟨ꙃ⟩ (*d͡z) with the fricative ⟨ꙁ⟩ (*z), realized consistently in Cyrillic and partially in Glagolitic manuscripts[76]

- Use of the past participle in perfect and past perfect tense without an auxiliary to denote the narator's attitude to what is happening[77]

Moreover, consistent scribal errors indicate the following trends in the development of the recension(s) between the 9th and the 11th centuries:

- Loss of the yers (ъ & ь) in weak position and their vocalization in strong position, with diverging results in Preslav and Ohrid[78][79][75]

- Depalatalization of ⟨ж⟩ (*ʒ), ⟨ш⟩ (*ʃ), ⟨ч⟩ (*t͡ʃ), ⟨ꙃ⟩ (*d͡z), ⟨ц⟩ (*t͡s) and the ⟨щ⟩ & ⟨жд⟩ clusters.[79] They are only hard in modern Bulgarian/Macedonian/Torlak

- Loss of intervocalic /j/, followed by vowel assimilation and contraction: sěěhъ (denoting sějahъ) > sěahъ > sěhъ ('I sowed'), dobrajego > dobraego > dobraago > dobrago ('good', masc. gen. sing.)[74][80]

- Incipient denasalization of the small yus, ѧ (ę), replaced with є (e)[81]

- Loss of the present tense third person sing. ending -тъ (tъ), e.g., бѫдетъ (bǫdetъ) > бѫде (bǫde) (lacking in modern Bugarian/Macedonian/Torlak)[82]

- Incipient replacement of the sigmatic and asigmatic aorist with the new aorist, e.g., vedoxъ instead of vedъ or věsъ (modern Bugarian/Macedonian and, in part, Torlak use similar forms)[83]

- Incipent analytisms, including examples of weakening of the noun declension, use of a postpositive definite article, infinitive decomposition > use of da constructions, future tense with хотѣти (> ще/ќе/че in Bulgarian/Macedonian/Torlak) can all be observed in 10-11th century manuscripts[84]

There are also certain differences between the Preslav and Ohrid recensions. According to Huntley, the primary ones are the diverging development of the strong yers (Western: ъ > o (*ɔ) and ь > є (*ɛ), Eastern ъ and ь > *ə), and the palatalization of dentals and labials before front vowels in East but not West.[85] These continue to be among the primary differences between Eastern Bulgarian and Western Bulgarian/Macedonian to this day. Moreover, two different styles (or redactions) can be distinguished at Preslav; Preslav Double-Yer (ъ ≠ ь) and Preslav Single-Yer (ъ = ь, usually > ь). The Preslav and Ohrid recensions are described in greater detail below:

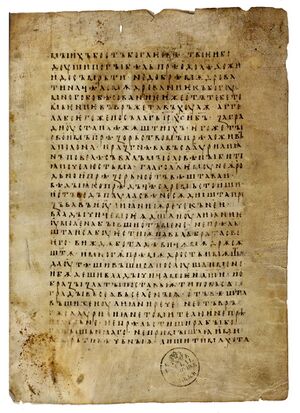

Preslav recension

The manuscripts of the Preslav recension[86][53][28] or "Eastern" variant[87] are among the oldest of the Old Church Slavonic language, only predated by the Moravian recension. This recension was centred around the Preslav Literary School. Since the earliest datable Cyrillic inscriptions were found in the area of Preslav, it is this school which is credited with the development of the Cyrillic alphabet which gradually replaced the Glagolitic one.[88][89] A number of prominent Bulgarian writers and scholars worked at the Preslav Literary School, including Naum of Preslav (until 893), Constantine of Preslav, John Exarch, Chernorizets Hrabar, etc. The main linguistic features of this recension are the following:

- The Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabets were used concurrently

- In some documents, the original supershort vowels ъ and ь merged with one letter taking the place of the other

- The original ascending reflex (rь, lь) of syllabic /r/ and /l/ was sometimes metathesized to (ьr, ьl), or a combination of the two

- The central vowel ы (ꙑ) merged with ъи (ъj)

- Merger of ⟨ꙃ⟩ (*d͡z) and ⟨ꙁ⟩ (*z)

- The verb forms нарицаѭ, нарицаѥши (naricajǫ, naricaješi) were substituted or alternated with наричꙗѭ, наричꙗеши (naričjajǫ, naričjaješi)

Ohrid recension

The manuscripts of the Ohrid recension or "Western" variant[90] are among the oldest of the Old Church Slavonic language, only predated by the Moravian recension. The recension is sometimes named Macedonian because its literary centre, Ohrid, lies in the historical region of Macedonia. At that period, Ohrid administratively formed part of the province of Kutmichevitsa in the First Bulgarian Empire until the Byzantine conquest.[91] The main literary centre of this dialect was the Ohrid Literary School, whose most prominent member and most likely founder, was Saint Clement of Ohrid who was commissioned by Boris I of Bulgaria to teach and instruct the future clergy of the state in the Slavonic language. This recension is represented by the Codex Zographensis and Marianus, among others. The main linguistic features of this recension include:

- Continuous usage of the Glagolitic alphabet instead of Cyrillic

- Strict distinction in the articulation of the yers and their vocalisation in strong position (ъ > *ɔ and ь > *ɛ) or deletion in weak position[48]

- Wider usage and retention of the phoneme *d͡z (which in most other Slavic languages has dеaffricated to *z)

Later recensions

Old Church Slavonic may have reached Slovenia as early as Cyril and Methodius's Panonian mission in 868 and is exemplified by the late 10th century Freising fragments, written in the Latin script.[92] Later, in the 10th century, Glagolitic liturgy was carried from Bohemia to Croatia, where it established a rich literary tradition.[92] Old Church Slavonic in the Cyrillic script was in turn transmitted from Bulgaria to Serbia in the 10th century and to Kievan Rus' in connection with its adoption of Orthodox Christianity in 988.[93][94]

The later use of Old Church Slavonic in these medieval Slavic polities resulted in a gradual adjustment of the language to the local vernacular, while still retaining a number of Eastern South Slavic, Moravian or Bulgarian features. In all cases, yuses denasalised so that only Old Church Slavonic, modern Polish and some isolated Bulgarian dialects retained the old Slavonic nasal vowels.

In addition to the Czech-Moravian recension, which became moribund in the late 1000s, four other major recensions can be identified: (Middle) Bulgarian, as a continuation of the literary tradition of the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools, Croatian, Serbian and Russian.[95] Certain authors also talk about separate Bosnian and Ruthenian recensions, whereas the use of the Bulgarian Euthimian recension in Wallachia and Moldova from the late 1300s until the early 1700s is sometimes referred to as "Daco-Slavonic" or "Dacian" recension.[96] All of these later versions of Old Church Slavonic are collectively referred to as Church Slavonic.[53]

Bosnian recension

The Bosnian recension used both the Glagolitic alphabet and the Cyrillic alphabet. A home-grown version of the Cyrillic alphabet, commonly known as Bosančica, or Bosnian Cyrillic, emerged very early on (probably the 1000s).[97][98][99] Primary features:

- Use of the letters i, y, ě for *i in Bosnian manuscripts (reflecting Bosnian Ikavism)

- Use of the letter djerv (Ꙉꙉ) for the Serbo-Croatian reflexes of Pra-Slavic *tj and *dj (*t͡ɕ & *d͡ʑ)

- Djerv was also used denote palatal *l and *n: ⟨ꙉл⟩ = *ʎ, ⟨ꙉн⟩ = *ɲ

- Use of the letter Щщ for Pra-Slavic *stj, *skj (reflecting pronunciation as *ʃt or *ʃt͡ʃ) and only rarely for *tj

The recension is sometimes subsumed under the Serbian recension, especially by Serbian linguistics, and (along with Bosančica) is generally the subject of a tug-of-war between Serbs, Croatians and Bosniaks.[100]

Middle Bulgarian

The common term "Middle Bulgarian" is usually contrasted to "Old Bulgarian" (an alternative name for Old Church Slavonic), and loosely used for manuscripts whose language demonstrates a broad spectrum of regional and temporal dialect features after the 11th century (12th to 14th century, although alternative periodisation exists, as well).[101][102][103] An alternative term, Bulgarian recension of Church Slavonic, is used by some authors.[104] The period is generally defined as a transition from the synthetic Old Bulgarian to the highly analytic New Bulgarian and Macedonian, where incipient 10th-century analytisms gradually spread from the north-east to all Bulgarian, Macedonian dialects and Torlak. Primary features:

Phonological

- Merger of the yuses, *ǫ=*ę (Ѫѫ=Ѧѧ), into a single mid back unrounded vowel (most likely ʌ̃), where ѫ was used after plain and ѧ after palatal consonants (1000s–1100s), followed by denasalization and transition of ѫ > *ɤ or *a and ѧ > *ɛ in most dialects (1200s-1300s)[105][106]

- Str. *ě > *ja (ʲa) in Eastern Bulgarian, starting from the 1100s; вꙗнєцъ (vjanec) instead of вѣнєцъ (v(j)ænec), from earlier вѣньцъ (v(j)ænьc) ('wreath'), after vocalization of the strong front yer[107]

- *ě > *e starting from northwestern Macedonia and spreading east and south, 1200s[108]

- *cě > *ca & *dzě > *dza in eastern North Macedonia and western Bulgaria (yakavian at the time), цаловати (calovati) instead of цѣловати (c(j)ælovati) ('kiss'), indicating hardening of palatal *c & *dz before *ě, 1200s[109]

- Merger of the yuses and yers (*ǫ=*ę=*ъ=*ь), usually, but not always, into a schwa-like sound (1200–1300s) in some dialects (central Bulgaria, the Rhodopes).[110] Merger preserved in the most archaic Rup dialects, e.g., Smolyan (> ɒ), Paulician (incl. Banat Bulgarian), Zlatograd, Hvoyna (all > ɤ)

Morphological

- Degradation of the noun declension and incorrect use of most cases or their replacement of preposition + dative or accusative by the late 1300s[111]

- Further development and grammaticalization of the short demonstrative pronouns into postpositive definite articles, e.g., сладостьтѫ ('the sweetness')[112]

- Emergence of analytic comparative of adjectives, побогатъ ('richer'), подобръ ('better') by the 1300s[113]

- Emergence of a single plural form for adjectives by the 1300s

- Disappearance of the supine, replaced by the infinitive, which in turn was replaced by da + present tense constructions by the late 1300s

- Disappearance of the present active, present passive and past active participle and the widening of the use of the l-participle (reklъ) and the past passive participle (rečenъ) ('said')

- Replacement of aorist plural forms -oxomъ, -oste, -ošę with -oxmy/oxme, -oxte, -oxǫ as early as the 1100s, e.g., рекохѫ (rekoxǫ) instead of рекошѧ (rekošę) ('they said')[114]

Euthymian recension

In the early 1370s, Bulgarian Patriarch Euthymius of Tarnovo implemented a reform to standardize Bulgarian orthography.[115] Instead of bringining the language closer to that of commoners, the "Euthymian", or Tarnovo, recension, rather sought to re-establish older Old Church Slavonic models, further archaizing it.[116] The fall of Bulgaria under Ottoman rule in 1396 precipitated an exodus of Bulgarian men-of-letters, e.g., Cyprian, Gregory Tsamblak, Constantine of Kostenets, etc. to Wallachia, Moldova and the Grand Duchies of Lithuania and Moscow, where they enforced the Euthymian recension as liturgical and chancery language, and to the Serbian Despotate, where it influenced the Resava School.[117][118]

Croatian recension

The Croatian recension of Old Church Slavonic used only the Glagolitic alphabet of angular Croatian type. It shows the development of the following characteristics:

- Denasalisation of PSl. *ę > e, PSl. *ǫ > u, e.g., OCS rǫka ("hand") > Cr. ruka, OCS językъ > Cr. jezik ("tongue, language")

- PSl. *y > i, e.g., OCS byti > Cr. biti ("to be")

- PSl. weak-positioned yers *ъ and *ь merged, probably representing some schwa-like sound, and only one of the letters was used (usually 'ъ'). Evident in earliest documents like Baška tablet.

- PSl. strong-positioned yers *ъ and *ь were vocalized into *a in most Štokavian and Čakavian dialects, e.g., OCS pьsъ > Cr. pas ("dog")

- PSl. hard and soft syllabic liquids *r and *r′ retained syllabicity and were written as simply r, as opposed to OCS sequences of mostly rь and rъ, e.g., krstъ and trgъ as opposed to OCS krьstъ and trъgъ ("cross", "market")

- PSl. #vьC and #vъC > #uC, e.g., OCS. vъdova ("widow") > Cr. udova

Russian recension

The Russian recension emerged in the 1000s based on the earlier Eastern Bulgarian recension, from which it differed slightly. The earliest manuscript to contain Russian elements is the Ostromir Gospel of 1056–1057, which exemplifies the beginning of a Russianized Church Slavonic that gradually spread to liturgical and chancery documents.[119] The Russianization process was cut short in the late 1300s, when a series of Bulgarian prelates, starting with Cyprian, consciously ‘‘re-Bulgarized’’ church texts to achieve maximum conformity with the Euthymian recension.[120][121] The Russianization process resumed in the late 1400s, and Russian Church Slavonic eventually became entrenched as standard for all Orthodox Slavs, incl. Serbs and Bulgarians, by the early 1800s.[122]

- PSl. *ę > *ja/ʲa, PSl. *ǫ > u, e.g., OCS rǫka ("hand") > Rus. ruka; OCS językъ > Rus. jazyk ("tongue, language")[123]

- Vocalisation of the yers in strong position (ъ > *ɔ and ь > *ɛ) and their deletion in weak position

- *ě > *e, e.g., OCS věra ("faith") > Rus. vera

- Preservation of a number of South Slavic and Bulgarian phonological and morphological features, e.g.[124]

- - ⟨щ⟩ (pronounced *ʃt͡ʃ) instead of East Slavic ⟨ч⟩ (*t͡ʃ) for Pra-Slavic *tj/*gt/*kt: просвещение (prosveščenie) vs. Ukrainian освiчення (osvičennja) ('illumination')

- - ⟨жд⟩ (*ʒd) instead of East Slavic ⟨ж⟩ (*ʒ) for Pra-Slavic *dj: одежда (odežda) vs. Ukrainian одежа (odeža) ('clothing')

- - Non-pleophonic -ra/-la instead of East Slavic pleophonic -oro/-olo forms: награда (nagrada) vs. Ukrainian нагoрoда (nahoroda) ('reward')

- - Prefixes so-/voz-/iz- instead of s-/vz- (z-)/vy-: возбудить (vozbuditь), vs. Ukrainian збудити (zbudyty) ('arouse'), etc.

Ruthenian recension

The Ruthenian recension generally shows the same characteristics as and is usually subsumed under the Russian recension. The Euthymian recension that was pursued throughout the 1400s was gradually replaced in the 1500s by Ruthenian, an administrative language based on the Belarusian dialect of Vilno.[125]

Serbian recension

The Serbian recension[126] was written mostly in Cyrillic, but also in the Glagolitic alphabet (depending on region); by the 12th century the Serbs used exclusively the Cyrillic alphabet (and Latin script in coastal areas). The 1186 Miroslav Gospels belong to the Serbian recension. They feature the following linguistic characteristics:

- Nasal vowels were denasalised and in one case closed: *ę > e, *ǫ > u, e.g. OCS rǫka > Sr. ruka ("hand"), OCS językъ > Sr. jezik ("tongue, language")

- Extensive use of diacritical signs by the Resava dialect

- Use of letters i, y for the sound /i/ in other manuscripts of the Serbian recension

- Use of djerv (Ꙉꙉ) for *d͡ʑ, *d͡ʒ and *tɕ (also used in the Bosnian recension)

Resava recension

Due to the Ottoman conquest of Bulgaria in 1396, Serbia saw an influx of educated scribes and clergy, who re-introduced a more classical form that resembled more closely the Bulgarian recension. In the late 1400s and early 1500s, the Resava orthography spread to Bulgaria and North Macedonia and exerted substantial influence on Wallachia. It was eventually superseded by Russian Church Slavonic in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Role in modern Slavic languages

Old Church Slavonic was initially widely intelligible across the Slavic world.[127] However, with the gradual differentiation of individual languages, Orthodox Slavs and, to some extent, Croatians ended up in a situation of diglossia, where they used one Slavic language for religious and another one for everyday affairs.[128] The resolution of this situation, and the choice made for the exact balance between Old Church Slavonic and vernacular elements and forms is key to understanding the relationship between (Old) Church Slavonic and modern Slavic literary languages, as well as the distance between individual languages.[129]

It was first Russian polymath and grammarian Mikhail Lomonosov that defined in 1755 "three styles" to the balance of Church Slavonic and Russian elements in the Russian literary language: a high style—with substantial Old Church Slavonic influence—for formal occasions and heroic poems; a low style—with substantial influence of the vernacular—for comedy, prose and ordinary affairs; and a middle style, balancing between the two, for informal verse epistles, satire, etc.[130][131]

The middle, "Slaveno-Russian", style eventually prevailed.[130] Thus, while standard Russian was codified on the basis of the Central Russian dialect and the Moscow chancery language, it retains an entire stylistic layer of Church Slavonisms with typically Eastern South Slavic phonetic features.[132] Where native and Church Slavonic terms exist side by side, the Church Slavonic one is in the higher stylistic register and is usually more abstract, e.g., the neutral город (gorod) vs. the poetic град (grаd) ('town').[133]

Bulgarian faced a similar dilemma a century later, with three camps championing Church Slavonic, Slaveno-Bulgarian, and New Bulgarian as a basis for the codification of modern Bulgarian.[130] Here the proponents of the analytic vernacular eventually won. However, the language re-imported a vast number of Church Slavonic forms, regarded as a legacy of Old Bulgarian, either directly from Russian Church Slavonic or through the mediation of Russian.[134]

By contrast, Serbian made a clean break with (Old) Church Slavonic in the first half of the 1800s, as part of Vuk Karadžić's linguistic reform, opting instead to build the modern Serbian language from the ground up, based on the Eastern Herzegovinian dialect. Ukrainian and Belarussian as well as Macedonian took a similar path in the mid and late 1800s and the late 1940s, respectively, the former two because of the association of Old Church Slavonic with stifling Russian imperial control and the latter in an attempt to distance the newly-codified language as further away from Bulgarian as possible.[135][136]

Canon

The core corpus of Old Church Slavonic manuscripts is usually referred to as canon. Manuscripts must satisfy certain linguistic, chronological and cultural criteria to be incorporated into the canon: they must not significantly depart from the language and tradition of Saints Cyril and Methodius, usually known as the Cyrillo-Methodian tradition.

For example, the Freising Fragments, dating from the 10th century, show some linguistic and cultural traits of Old Church Slavonic, but they are usually not included in the canon, as some of the phonological features of the writings appear to belong to certain Pannonian Slavic dialect of the period. Similarly, the Ostromir Gospels exhibits dialectal features that classify it as East Slavic, rather than South Slavic so it is not included in the canon either. On the other hand, the Kiev Missal is included in the canon even though it manifests some West Slavic features and contains Western liturgy because of the Bulgarian linguistic layer and connection to the Moravian mission.

Manuscripts are usually classified in two groups, depending on the alphabet used, Cyrillic or Glagolitic. With the exception of the Kiev Missal and Glagolita Clozianus, which exhibit West Slavic and Croatian features respectively, all Glagolitic texts are assumed to be of the Macedonian recension:

- Kiev Missal (Ki, KM), seven folios, late 10th century

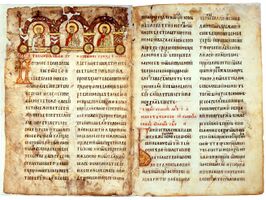

- Codex Zographensis, (Zo), 288 folios, 10th or 11th century

- Codex Marianus (Mar), 173 folios, early 11th century

- Codex Assemanius (Ass), 158 folios, early 11th century

- Psalterium Sinaiticum (Pas, Ps. sin.), 177 folios, 11th century

- Euchologium Sinaiticum (Eu, Euch), 109 folios, 11th century

- Glagolita Clozianus (Clo, Cloz), 14 folios, 11th century

- Ohrid Folios (Ohr), 2 folios, 11th century

- Rila Folios (Ri, Ril), 2 folios and 5 fragments, 11th century

All Cyrillic manuscripts are of the Preslav recension (Preslav Literary School) and date from the 11th century except for the Zographos, which is of the Ohrid recension (Ohrid Literary School):

- Sava's book (Sa, Sav), 126 folios

- Codex Suprasliensis, (Supr), 284 folios

- Enina Apostle (En, Enin), 39 folios

- Hilandar Folios (Hds, Hil), 2 folios

- Undol'skij's Fragments (Und), 2 folios

- Macedonian Folio (Mac), 1 folio

- Zographos Fragments (Zogr. Fr.), 2 folios

- Sluck Psalter (Ps. Sl., Sl), 5 folios

Sample text

Here is the Lord's Prayer in Old Church Slavonic:

| Cyrillic | IPA | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

[[[:قالب:Poetically break lines]]] Error: {{Transliteration}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 4: ق) (help) |

Authors

The history of Old Church Slavonic writing includes a northern tradition begun by the mission to Great Moravia, including a short mission in the Lower Pannonia, and a Bulgarian tradition begun by some of the missionaries who relocated to Bulgaria after the expulsion from Great Moravia.

The first texts written in Old Church Slavonic are translations of the Gospels and Byzantine liturgical texts[9] begun by the Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius, mostly during their mission to Great Moravia.

The most important authors in Old Church Slavonic after the death of Methodius and the dissolution of the Great Moravian academy were Clement of Ohrid (active also in Great Moravia), Constantine of Preslav, Chernorizetz Hrabar and John Exarch, all of whom worked in medieval Bulgaria at the end of the 9th and the beginning of the 10th century. The full text of the Second Book of Enoch is only preserved in Old Church Slavonic, although the original most certainly had been in Greek or even Hebrew or Aramaic.

Modern Slavic nomenclature

Here are some of the names used by speakers of modern Slavic languages:

- بالبيلاروسية: стараславянская мова (starasłavianskaja mova), 'Old Slavic language'

- بالبلغارية: старобългарски (starobalgarski), 'Old Bulgarian' and старославянски,[137] (staroslavyanski), 'Old Slavic'

- تشيكية: staroslověnština, 'Old Slavic'

- مقدونية: старословенски (staroslovenski), 'Old Slavic'

- پولندية: staro-cerkiewno-słowiański, 'Old Church Slavic'

- روسية: старославянский язык (staroslavjánskij jazýk), 'Old Slavic language'

- قالب:Lang-sh-Latn, الكيريلية الصربوكرواتية: старословенски / старославенски, 'Old Slavic'

- سلوڤاكية: staroslovienčina, 'Old Slavic'

- Slovene: stara cerkvena slovanščina, 'Old Church Slavic'

- أوكرانية: староцерковнослов'янська мова (starotserkovnoslovjans'ka mova), 'Old Church Slavic language'

See also

- Outline of Slavic history and culture

- List of Slavic studies journals

- History of the Bulgarian language

- Church Slavonic language

- Old East Slavic

- List of Glagolitic manuscripts

- Proto-Slavic language

- Slavonic-Serbian

Notes

- ^ Also known as Old Church Slavic,[1][2] Old Slavic (/ˈslɑːvɪk, ˈslæv-/), Paleo-Slavic, Paleoslavic, Palaeo-Slavic, Palaeoslavic[3] (not to be confused with Proto-Slavic), or sometimes as Old Bulgarian, Old Macedonian or Old Slovenian.[4][5][6][7][8]

- ^ Slavs had invaded the region from about 550 CE.[31]

References

- ^ أ ب Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1-40588118-0

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003), Roach, Peter; Hartmann, James; Setter, Jane, eds., English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- ^ Malkiel 1993, p. 10.

- ^ Lunt, Horace G. (1974). Old Church Slavonic grammar – With an epilogue: Toward a generative phonology of Old Church Slavonic. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 3, 4. ISBN 978-3-11-119191-1.

Since the majority of the early manuscripts which have survived were copied in the Bulgaro-Macedonian area and since there are certain specifically Eastern Balkan Slavic features, many scholars have preferred to call the language Old Bulgarian, although Old Macedonian could also be justified. In the nineteenth century there was a theory that this language was based on the dialect of Pannonia, and accordingly the term Old Slovenian was adopted for a time. … The older term "Middle Bulgarian", invented to distinguish younger texts from "Old Bulgarian" (=OCS), covers both the fairly numerous mss from Macedonia and the few from Bulgaria proper. There are some texts which are hard to classify because they show mixed traits: Macedonian, Bulgarian and Serbian.

- ^ Gamanovich, Alypy (2001). Grammar of the Church Slavonic Language. Printshop of St Job of Pochaev: Holy Trinity Monastery. p. 9. ISBN 0-88465064-2.

The Old Church Slavonic language is based on Old Bulgarian, as spoken by the Slavs of the Macedonian district. In those days the linguistic differences between the various Slavic peoples were far less than they are today…

- ^ Flier, Michael S (1974). Aspects of Nominal Determination in Old Church Slavic. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 31. ISBN 978-90-279-3242-6.

'Old Church Slavic' is only one of many terms referring alternately to the language of a number of translations made by Cyril and Methodius in the middle of the ninth century to be used for liturgical purposes in the Great Moravian State,… (For example, Old Church Slavonic, Old Bulgarian, Old Slovenian.)

- ^ Adams, Charles Kendall (1876). Universal Cyclopædia and Atlas. Vol. 10. D. Appleton. pp. 561–2. ISBN 978-1-23010206-1.

Constantine (later called Monk Cyril) founded a literary language for all the Slavs – the so-called Church Slavonic or Old Bulgarian (or Old Slovenian), which served for many centuries as the organ of the Church and of Christian civilization for more than half of the Slavic race. … At the outset Dobrowsky recognized in it a southern dialect, which he called at first Old Servian, later Bulgaro-Servian or Macedonian. Kopitar advanced the hypothesis of a Pannonian-Carantanian origin, which Miklosich followed with slight modifications. From these two scholars comes the name Old Slovenian. Safarik defended the Old Bulgarian hypothesis, more on historical than on linguistic grounds. The name Old Slovenian is still used because in native sources the language was so-called, slovenisku (slovenica lingua), but it is now known to have been a South Slavic dialect spoken somewhere in Macedonia in the ninth century, having the most points of contact not with modern Slovenian, but with Bulgarian.

- ^ Arthur De Bray, Reginald George (1969). Guide to the Slavonic Languages. J. M. Dent & Sons. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-46003913-0.

This book starts with a brief summary of the phonetics and grammar of Old Slavonic (also called Old Bulgarian).

- ^ أ ب Abraham, Ladislas (1908). "Sts. Cyril and Methodius". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2023-08-02.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 752.

- ^ Čiževskij, Dmitrij (1971). "The Beginnings of Slavic Literature". Comparative History of Slavic Literatures. Translated by Porter, Richard Noel; Rice, Martin P. Vanderbilt University Press (published 2000). p. 27. ISBN 978-0-82651371-7. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

The language of the translations was based on Old Bulgarian and was certainly close to the Old Bulgarian dialect spoken in the native region of the missionaries. At the same time, the brothers [Cyril and Methodius] probably used elements, particularly lexical, from the regions where they were working. […] The Slavic language used in the translations was at the time intelligible to all Slavs.

- ^ Nandris 1959, p. 2.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Ziffer, Giorgio – On the Historicity of Old Church Slavonic UDK 811.163.1(091) Archived 2008-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ A. Leskien, Handbuch der altbulgarischen (altkirchenslavischen) Sprache, 6. Aufl., Heidelberg 1922.

- ^ A. Leskien, Grammatik der altbulgarischen (altkirchenslavischen) Sprache, 2.-3. Aufl., Heidelberg 1919.

- ^ أ ب "American contributions to the Tenth International Congress of Slavists", Sofia, September 1988, Alexander M. Schenker, Slavica, 1988, ISBN 0-89357-190-3, pp. 46–47.

- ^ J P Mallory, D Q Adams. Encyclopaedia of Indo-European Culture. Pg 301 "Old Church Slavonic, the liturgical language of the Eastern Orthodox Church, is based on the Thessalonican dialect of Old Macedonian, one of the South Slavic languages."

- ^ R. E. Asher, J. M. Y. Simpson. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, Introduction "Macedonian is descended from the dialects of Slavic speakers who settled in the Balkan peninsula during the 6th and 7th centuries CE. The oldest attested Slavic language, Old Church Slavonic, was based on dialects spoken around Salonica, in what is today Greek Macedonia. As it came to be defined in the 19th century, geographic Macedonia is the region bounded by Mount Olympus, the Pindus range, Mount Shar and Osogovo, the western Rhodopes, the lower course of the river Mesta (Greek Nestos), and the Aegean Sea. Many languages are spoken in the region but it is the Slavic dialects to which the glossonym Macedonian is applied."

- ^ R. E. Asher, J. M. Y. Simpson. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, History, "Modern Macedonian literary activity began in the early 19th century among intellectuals attempt to write their Slavic vernacular instead of Church Slavonic. Two centers of Balkan Slavic literary arose, one in what is now northeastern Bulgaria, the other in what is now southwestern Macedonia. In the early 19th century, all these intellectuals called their language Bulgarian, but a struggled emerged between those who favored northeastern Bulgarian dialects and those who favored western Macedonian dialects as the basis for what would become the standard language. Northeastern Bulgarian became the basis of standard Bulgarian, and Macedonian intellectuals began to work for a separate Macedonian literary language. "

- ^ Tschizewskij, Dmitrij (2000) [1971]. Comparative History of Slavic Literatures. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-826-51371-7. "The brothers knew the Old Bulgarian or Old Macedonian dialect spoken around Thessalonica."

- ^ Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, pg. 431 "Macedonian was not distinguished from Bulgarian for most of its history. Constantine and Methodius came from Macedonian Thessaloniki; their old Bulgarian is therefore at the same time 'Old Macedonian'. No Macedonian literature dates from earlier than the nineteenth century, when a nationalist movement came to the fore and a literacy language was established, first written with Greek letters, then in Cyrillic"

- ^ Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, p. 427 "The Old Church Slavonic of Bulgaria, regarded as something of a standard, is often called Old Bulgarian (or Old Macedonian)"

- ^ Henry R. Cooper. Slavic Scriptures: The Formation of the Church Slavonic Version of the Holy Bible, p. 86 "We do not know what portions of the Bible in Church Slavonic, let alone a full one, were available in Macedonia by Clement's death. And although we might wish to make Clement and Naum patron saints of such as glagolitic-script, Macedonian-recension Church Slavonic Bible, their precise contributions to it we will have to take largely on faith."

- ^ أ ب Birnbaum, Henrik (1974). On Medieval and Renaissance Slavic Writing. Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 9783-1-1186890-5.

- ^ Lunt 2001, p. 4.

- ^ The Universal Cyclopaedia. 1900.

- ^ أ ب Kamusella 2008[صفحة مطلوبة].

- ^ Huntley 1993, pp. 23.

- ^ Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 214.

- ^ Duridanov 1991, pp. 527.

- ^ Huntley 1993, pp. 23 [Skepticism about this has centred around the speed with which everything was done, apparently no more than a year having passed between the request and the mission, a short time for the creation of an excellent alphabet plus the translation into a Slavonic language, using this new alphabet, of at least the Gospels. The only response has been that Constantine's philological interest might have led him to 'play' with an alphabet before this.].

- ^ Fine, J. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans, A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. pp. 113–114. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

Since Constantine and Methodius were able to have both language and translations ready so promptly, they must have been at work upon this project for some time prior to Rastislav's request. If so, presumably their efforts had been originally aimed at a future mission for Bulgaria. This also would explain why Old Church Slavonic had a Bulgaro-Macedonian base; this dialect was well suited as a missionary language for Bulgaria.

- ^ Hupchick, Dennis (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4039-6417-5.

- ^ Alexander 2005, p. 310.

- ^ Price, Glanville (2000-05-18). Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-63122039-8.

- ^ Parry, Ken (2010-05-10). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-44433361-9.

- ^ Rosenqvist, Jan Olof (2004). Interaction and Isolation in Late Byzantine Culture. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-85043944-8.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 221–22.

- ^ Silent Communication: Graffiti from the Monastery of Ravna, Bulgaria. Studien Dokumentationen. Mitteilungen der ANISA. Verein für die Erforschung und Erhaltung der Altertümer, im speziellen der Felsbilder in den österreichischen Alpen (Verein ANISA: Grömbing, 1996) 17. Jahrgang/Heft 1, 57–78.

- ^ "The scriptorium of the Ravna monastery: once again on the decoration of the Old Bulgarian manuscripts 9th–10th c." In: Medieval Christian Europe: East and West. Traditions, Values, Communications. Eds. Gjuzelev, V. and Miltenova, A. (Sofia: Gutenberg Publishing House, 2002), 719–26 (with K. Popkonstantinov).

- ^ Popkonstantinov, Kazimir, "Die Inschriften des Felsklosters Murfatlar". In: Die slawischen Sprachen 10, 1986, S. 77–106.

- ^ Gasparov, B (2010). Speech, Memory, and Meaning. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-311021910-4.

- ^ "Bdinski Zbornik [manuscript]". Lib. U Gent. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Тодорова-Гергова, Светлана. Отец Траян Горанов: За богослужението на съвременен български език, Българско национално радио ″Христо Ботев″, 1 април 2021 г.

- ^ Lunt 2001, pp. 15–6.

- ^ أ ب Huntley 1993, pp. 126–7.

- ^ Duridanov (1991), pp. 65: Че някога на всички македонски говори са били присъщи звукосъчетанията шт, жд на мястото на днешните ќ, ѓ се вижда от топонимията на съответните области: Брьждaни (при Кичево), Драгощь и Хращани (в Битолско), Вел‘гощи, Радобужда, Радов'лища и Пещани (в Охридско), Граждено (в Ресенско), Рожденъ (в Тиквеш) — всички данни са от XVI в. (Селищев 1933 а: 22, 38, 63, 64 и др.; 1933 б: 37)… Днешното селищно име в Прилепско Кривогащани е познато под тая форма в грамота от XIV в.: въ Кривогаштанехъ (Новаковић 1912: 666). В околия Крива Паланка (Северна Македония) също се срещат местни имена с шт, жд: Бащево, Радибуш — от Радибоужда (Радибоуждоу Горноу) в грамота от 1358 г, (Новаковић 1912: 435); в Кочанско: Драгобраща; в Скопско: Пещерица, Побуже — Побѫжда във Виргинската грамота на Константин Асен от ХШ в. (Иванов 1931: 582), Смрьдештець в грамота от 1300г. (Селищев 1933 6: 38) и др.; срв. още селищното име Радовиш от по-старо *Радовишти, в грамота от 1361 г. (Селищев 1933 б: 38). В Призренско също са засвидетелствувани географски имена с шт, жд, срв. примерите в една грамота от XIV в. (Селищев 1933 б: 40): Небрѣгошта, Доброушта, Сѣлограждани, Гражденикь, Послища, Любижда и т. н. На запад ареалът на старобългарските говори ще е обхващал поречията на Южна Морава и Тимок, както може да се съди от цяла поредица географски (главно селищни) имена с шт, жд от праславянско *tj, *kt, *dj, запазени до най-ново време. Срв. напр.: Добровиш (от по-старо Добровищь) — село в Пиротско; Добруща (от XIV в.) — село близо до Гиляни; Огоща — село в околия Гиляни; Тибужде, Драгобужда (-жде), Рождаци (-це) (срв. срблг. рождакъ в Слепченския апостол, срхърв. рођак „сродник“, „роднина“) — села в околия Враня; Житоражда — две села в околия Прокупле и околия Владичин хан; Люберажда — село в Пиротско; Ображда — село в околия Лебани; Ргоште — село в Тимошка околия (от основа Ргот-, от коята са Рготина, село в Зайчарска околия и Рготска река), Драгаиште — приток на Тимок и пр. Някои от тези реликтни топоними са вече посърбени (напр в официалните сръбски справочници се пише Житорађе, Љуберађа), но повечето са запазили първоначалното си звучене. [The fact that all Macedonian dialects once featured the consonant clusters шт/št ([ʃt]) and жд/žd [ʒd] instead of today's ќ (/c/) and ѓ (/ʄ/) can be seen from the toponyms in the respective regions: Brždani (near Kičevo), Dragošt and Hraštani (near Bitola), Vel'gošti, Radožda (from "Radobužda"), Radolišta (from "ou Radov'lišteh") and Peštani (near Ohrid ), Graždeno near Resen ([sic] now in Greece and known as Vrontero), Rožden (in Tikveš) — all data are from the 16th century (Selishchev 1933a: 22, 38, 63, 64, etc.; 1933b: 37)... The current name of one of the settlements around Prilep, Krivogaštani, has been known in this form from a charter from the 14th century: "in Krivogaštanekh" (Novakoviћ 1912: 666). In the vicinity of Kriva Palanka, there are also local names with št, žd: Baštevo, Radibuš — from "Radiboužda" (Radibouzhdou Gornou) in a charter from 1358, (Novakoviћ 1912: 435); in the Kochani region: Dragobrašte; near Negotino: Pešternica, near Skopje: Pobožje — known as "Побѫжда" (Pobăžda) in the Virgin Charter by Tsar Constantine Asen from the 13th century (Ivanov 1931: 582), Smrdeštec in a charter from 1300. (Selishchev 1933 6: 38) etc.; cf. also the settlement name Radoviš, stemming from the older "Радовишти" (*Radovišti), in a charter from 1361 (Selishchev 1933 b: 38). Geographical names with št, žd are also attested around Prizren in Kosovo, e.g., in a charter from the 14th century (Selishchev 1933 b: 40): Nebregoštesh, Dobrushta, Sallagrazhdë, Graždanik, Poslishtë, Lubizhdë, etc. In the West, the range of Old Bulgarian dialects would have extended to the river valleys of South Morava and Timok, as can be judged from a whole series of geographic names (mainly settlements) incorporating [ʃt] and [ʒd] from Proto-Slavic *tj, *kt, *dj, preserved until now or very recently. For example: Dobroviš (from the older "Добровищь" (Dobrovišt)) — a village near Pirot; Dobrushta (from the 14th century) and Ogošte — a village near Gjilan; Tibužde, Dragobužde, Roždace (cf. Middle Bulgarian "рождакь" in the Slepcha Apostle and compare with Serbo-Croat "roђak" ('relative')) — villages in the vicinity of Vranje, South Serbia; Žitoražda and Žitoražde — two villages near Prokuplje and Vladičin Han; Ljuberađa — a village near Pirot; Obražda — a village in the Lebane district; Rgošte — a village in the Knjaževac municipality (from the base Rgot-, which gives Rgotina, a village in the Zaječar municipality and the Rgotska river). Some of these relic toponyms have already been eroded (for example, the official Serbian directories now read Žitorađa/Žitorađe and Ljuberađa instead of Žitoražda/Žitoražde and Ljuberažda), but most names have kept their original articulation]

- ^ Huntley 1993, pp. 127–8.

- ^ Syllabic sonorant, written with jer in superscript, as opposed to the regular sequence of /r/ followed by a /ь/.

- ^ أ ب Huntley 1993, p. 133.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Sussex & Cubberley 2006, p. 64.

- ^ Townsend, Charles E.; Janda, Laura A. (1996) (in en), COMMON and COMPARATIVE SLAVIC: Phonology and Inflection, with special attention to Russian, Polish, Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Bulgarian, Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Publishers, Inc., pp. 89–90, ISBN 0-89357-264-0

- ^ Harasowska, Marta (2011), Morphophonemic Variability, Productivity, and Change: The Case of Rusyn, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 76, ISBN 978-3110804522

- ^ Hinskens, Frans; Kerswill, Paul; Auer, Peter (2005), Dialect Change. Convergence and Divergence in European Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 261, ISBN 9781139445351

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2006, p. 64: Strictly speaking, ‘‘Old Church Slavonic’’ refers only to the language of the early period, and to later writings which deliberately imitated it..

- ^ Lunt (2001:9) "The seven glagolitic folia known as the Kiev Folia (KF) are generally considered as most archaic from both the paleographic and the linguistic points of view..."

- ^ Huntley 1993, p. 30.

- ^ Fidlerová, Alena A.; Robert Dittmann; František Martínek; Kateřina Voleková. "Dějiny češtiny" (PDF) (in التشيكية). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ أ ب Sussex & Cubberley 2006, p. 43.

- ^ Ertl, Alan W (2008). Toward an Understanding of Europe. Universal-Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59942983-0.

- ^ Kostov, Chris (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-303430196-1.

- ^ Zlatar, Zdenko (2007). The Poetics of Slavdom: Part III: Njego. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-82048135-7.

- ^ Lunt 2001.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, p. 174.

- ^ Fortson, Benjamin W (2009-08-31). Indo-European Language and Culture. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-40518896-8.

- ^ Birnbaum, Henrik; Puhvel, Jaan (1966). Ancient Indo-European Dialects.

- ^ Kaliganov, I. "Razmyshlenija o makedonskom "sreze"…". kroraina.

- ^ Crampton 2005, p. 15.

- ^ Selishchev, Afanasii. Очерки по македонской диалектологии [Essays on Macedonian dialectology]. Kazan. pp. 127–146.

- ^ Mirchev (1958), pp. 155.

- ^ Georgiev, Vladimir (1985). Възникването на палаталните съгласни кʼ и гʼ от шт и жд в югозападните български говори, Проблеми на българския език [Emergence of Palatal /k'/ and /g'/ from [sht] and [zhd] in the Southwestern Bulgarian Dialects. Issues Relating to the Bulgarian Language]. p. 43.

- ^ أ ب Huntley (1993), pp. 132.

- ^ أ ب Mirchev (1958), pp. 55.

- ^ Huntley (1993), pp. 133.

- ^ Huntley (1993), pp. 153.

- ^ Huntley (1993), pp. 126–127.

- ^ أ ب Duridanov (1991), pp. 541–543.

- ^ Duridanov (1991), pp. 545–547.

- ^ Duridanov (1991), pp. 544.

- ^ Duridanov (1991), pp. 547.

- ^ Duridanov (1991), pp. 548.

- ^ Duridanov (1991), pp. 551–557.

- ^ Huntley (1993), pp. 129, 131.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce Manning (1977). The Early Versions of the New Testament. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19826170-4.

- ^ Birnbaum 1991, p. 535.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 221–222.

- ^ Hussey, J. M. (2010-03-25). The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19161488-0.

- ^ Stolz, Titunik & Doležel 1984, p. 111.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, p. 169.

- ^ أ ب Huntley 1993, p. 31.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2006, p. 84–85.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 218.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2006, p. 64–65.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 218, 277.

- ^ Marti 2012, p. 275.

- ^ Cleminson, Ralph (2000). Cyrillic books printed before 1701 in British and Irish collections: a union catalogue. British Library. ISBN 978-0-71234709-9.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 219–220: In the 14th century, the Cyrillic alphabet underwent reform under Bulgarian and Greek influence, but in inaccessible Bosnia, isolated from the outer world by mountain ranges, the Cyrillic developed into a special form known as Bosančica, or the 'Bosnian script'.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 976.

- ^ Gerald L. Mayer, 1988, The definite article in contemporary standard Bulgarian, Freie Universität Berlin. Osteuropa-Institut, Otto Harrassowitz, p. 108.

- ^ Bounatriou, Elias (2020). "Church Slavonic, Recensions of". Encyclopedia of Slavic Languages and Linguistics Online. doi:10.1163/2589-6229_ESLO_COM_032050.

- ^ Mirchev (1958), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 277.

- ^ Mirchev (1958), pp. 110–114.

- ^ Totomanova, Ana-Maria (2014). Из българската историческа фонетика [On Bulgarian Historical Phonetics] (III ed.). Sofia: University Printing House St. Clement of Ohrid. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-954-07-3788-1.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 15.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 20.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 19.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 18, 23.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 24.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 196–205.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 180.

- ^ Mirchev 1958, pp. 216, 218.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, pp. 276.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 85.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, pp. 158–159, 204, 276, 277: Bulgarian Church Slavonic was adopted as the official language of the Danubian Principalities and gradually developed into a specific Dacian recension that remained in use until the beginning of the 18th century.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 82, 85.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 82: The South Slavic component was deliberately emphasized during the ‘‘ Second South Slavic Influence’’ of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when Bulgarian prelates consciously ‘‘re-Bulgarized’’ (Issatschenko, 1980; 1980–1983) the church texts to achieve maximum conformity with the established church norms.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, pp. 158–159: These immigrants enforced the South Slavic (Bulgarian) recension (version) of Church Slavonic as the standard in which religious books were to be written and administration conducted in Muscovy. This trend had commenced at the end of the 14th century when a succession of South Slavic monks had been nominated to the position of the metropolitan of all Rus (sometimes, anachronistically translated as ‘all Russias’) with his seat at Moscow.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 82: In time, however, the Russian recension of Church Slavonic gained increasing acceptance in Russia, and came to influence Serbian and Bulgarian Church Slavonic, and the formation and revival of these literary languages.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 44

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 50.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 64, 85: During this period the written models included the ‘‘Euthymian’’ recension of Church Slavonic, an esoteric, Bulgarian-inspired attempt to re-establish older South Slavic models, which was then replaced by Ruthenian, a written and administrative language based on the Belarusian dialect of Vilno under Lithuanian rule.

- ^ Lunt 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 64.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 63–65.

- ^ أ ب ت Kamusella 2008, p. 280.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 477–478.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 478.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 480.

- ^ Sussex & Cubberley 2002, p. 86.

- ^ Kamusella 2008, p. 229.

- ^ Иванова-Мирчева 1969: Д. Иванова-Мнрчева. Старобългарски, старославянски и средно-българска редакция на старославянски. Константин Кирил Философ. В Юбилеен сборник по случай 1100 годишнината от смъртта му, стр. 45–62.

Bibliography

- Alexander, June Granatir (2005). "Slovakia". In Richard C. Frucht, ed., Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture, Volume 2: Central Europe, pp. 283–328. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-576-07800-6.

- Birnbaum, Henrik (1991). Aspects of the Slavic Middle Ages and Slavic Renaissance Culture. New York, NY: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-820-41057-9.

- Cizevskij, Dmitrij (2000) [1971]. Comparative History of Slavic Literatures. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-826-51371-7.

- Crampton, R. J. (2005). A Concise History of Bulgaria (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61637-9.

- Cubberley, Paul (2002). Russian: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79191-5.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- Duridanov, Ivan (1991). Граматика на старобългарския език [Grammar of Old Bulgarian] (in البلغارية). Sofia: Bulgarian Language Institute, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. ISBN 954-430-159-3.

- Huntley, David (1993). "Old Church Slavonic". In Bernard Comrie and Greville G. Corbett, eds., The Slavonic Languages, pp. 125–187. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04755-5.

- Kamusella, Tomasz (2008). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-29473-8.

- Lunt, Horace G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic Grammar (7th ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-16284-4.

- Malkiel, Yakov (1993). Etymology. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521311663.