سرگون من أكاد

- قد تكون تبحث عن الملوك الآشوريين سرگون الأول (حكم 1920–1881 ق.م.) أو سرگون الثاني (حكم 722–705 ق.م.).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

سرگون الأول (بالأكادية: ܫܪܘܟܢ، 𒈗𒁺 ؛ "شرّو كِن"، بمعنى الملك الاسد) هو مؤسس السلالة الأكادية. امتدت إمبراطوريته الواسعة من عيلام إلى البحر المتوسط، واشتمل ذلك بلاد الرافدين والأناضول. حكم منذ عام 2334 حتى 2279 ق.م.، من عاصمة جديدة وهي أكاد، التي تقع في الضفة اليسرى لنهر الفرات بالقرب من كيش.

يُعتقد أن امبراطورية سرگون مترامية الأطراف قد ضمت أجزاءً كبيرة من بلاد الرافدين، كما ضمت أجزاءً من إيران الحالية، آسيا الصغرى وسوريا. وقد حكم تلك الامبراطورية من عاصمة جديدة أكـّاد، التي لم يُعثر عليها حتى الآن، والتي تزعم قائمة الملوك السومريين أنه قد بناها (أو لعله جددها).[1] ويُعتبر أحياناً أول شخص في التاريخ المسجل يصنع إمبراطورية متعددة الأعراق، محكومة مركزياً، بالرغم من أن السومريين لوگل-أنـّى-موندو ولگل-زاگى-سي يدّعون نفس الانجاز. وقد ظلت أسرته مسيطرة على بلاد الرافدين لنحو قرن ونصف (150 سنة).[2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أصله ونشأته

ولم يكن سرجون هذا من أبناء الملوك، ولكن الأساطير السومرية إصطنعت له سيرة روتها على لسانه شبيهة في بدايتها بسيرة موسى، فهو يقول: "وحملت بي أمي الوضيعة الشأن، وأخرجتني إلى العالم سراً ووضعتني في قارب من السل كالسلة وأغلقت علىَّ الباب بالقار". وأنجاه أحد العمال، وأصبح فيما بعد ساقي الملك، فقربه إليه، وزاد نفوذه وسلطانه. ثم خرج على سيده وخلعه وجلس على عرش أكـّاد، وسمى نفسه "الملك صاحب السلطان العالي" وإن لم يكن يحكم إلا قسما صغيراً من أرض الجزيرة. ويسميه المؤرخون سرجون "الأعظم" لأنه غزا مدناً كثيرة، وغنم مغانم عظيمة، وأهلك عدداً كبيراً من الخلائق. وكان من بين ضحاياه لوگل-زاگى-سي نفسه الذي نهب لگش وانتهك حرمة آلهتها، فقد هزمه سرگون وساقه مقيداً بالأغلال إلى نيپور. وأخذ هذا الجندي الباسل يخضع البلاد شرقاً وغرباً، شمالاً وجنوباً، فاستولى على عيلام وغسل أسلحته في مياه الخليج الفارسي العظيم رمزاً لانتصاراته الباهرة، ثم إجتاز غرب آسية ووصل إلى البحر المتوسط، وظل يحكمها خمساً وخمسين سنةً، وتجمعت حوله الأساطير فهيأت عقول الأجيال التالية لأن تجعل منه إلهاً. وانتهى حكمه ونار الثورة مشتعلة في جميع أنحاء دولته.

بناء الامبراطورية الأكـّادية

بعد الاستيلاء على كيش، قام سرگون بقتل ملك كيش بعد أن استمال جيش كيش لجانبه، وسرعان ما هاجم سرگون اوروك، التي كان يحكمها لوگل-زاگى-سي من أمة. فاستولى على اوروك ونقض أسوارها الشهيرة. ويبدو أن المدافعين قد فروا من المدينة، وانضموا إلى جيش يقوده خمسون إنسي من المقاطعات. وقد خاضت تلك القوة السومرية معركتين حاميتي الوطيس ضد الأكاديين، ونتيجة لهما فقد تم دحر القوى الباقية من أتباع لوگل-زاگى-سي.[3] أما لوگل-زاگى-سي نفسه فقد أٌسِر وأُحضِر إلى نيپور، وقد نقش سرگون على قاعدة تمثال (محفوظ في لوح لاحق) أنه أحضر لوگل-زاگى-سي "في طوق كلب إلى بوابة إنليل."[4] طارد سرگون أعداءه إلى أور قبل أن يتجه شرقاً إلى لگش، ثم إلى الخليج العربي، ومن ثم إلى أُمـّة. وقد قام بلفتة رمزية بغسل أسلحته في "البحر الأسفل" (الخليج العربي) ليُظهـِر أنه قد أخضع سومر بالكامل.[4]

كما احتفل سرگون بنصره على كشتوبيلا، ملك كازالا. وحسب مصدر قديم، فإن سرگون دمر المدينة حتى أن "الطيور لم تجد مكاناً تعشش فيه."[5]

واتخذ بعد ذلك عاصمة جديدة لدولته الناشئة وسمّاها أكـّد (Akkad)، لتكون مقراً لحكمه، وذلك عام 2330ق.م تقريباً. وأقام هناك قصراً ومعبداً لزبابا إله الحرب، في كيش، ولعشتار التي ساعدته في الوصول إلى حكم البلاد. وقد بقيت هذه المدينة مركزاً للعالم القديم نحو قرن من الزمان، وكانت في ذلك الوقت المدينة الأكثر ثراء وأهمية في العالم. ومن هذه المدينة أخذ الأكّديون والامبراطورية الأكّدية واللغة الأكّدية أسماءهم، ولم يحدد مكانها بدقة إلى اليوم، ويُظن أنها تقع في المنطقة بين كيش، وبابل ومدينة سيبار.

ولكي يخفـِّض من احتمال الثورات في سومر، فقد عيـّن بلاطاً من 5,400 رجلاً "ليتقاسموا مائدته" (أي ليديروا الامبراطورية).[6] هؤلاء 5,400 رجل ربما كانوا جيشه.[7] الحكام الذين اختارهم سرگون لحكم المدن-الدول في سومر كانوا أكاديين، وليسوا سومريين.[8] وأصبحت اللغة الأكادية السامية هي اللغة السائدة والرسمية للمكاتبات والنقوش في جميع أرجاء بلاد الرافدين، وكان لها انتشار واسع خارج امبراطورية سرگون. فقد كان لإمبراطورية سرگون تجارة وعلاقات دبلوماسية مع الممالك المحيطة وغيرها في الشرق الأدنى. وتفيد نقوش سرگون بأن سفناً من مگان، ملوحا، ودلمون، بين أماكن أخرى، كانت ترسو في عاصمته أگادى.[9]

تواصل احترام المؤسسات الدينية السابقة في سومر، والتي كانت ذائعة الصيت ويقلدها الساميون. وظلت السومرية، لحد كبير، هي لغة الدين، وظل سرگون وخلفاؤه راعون للمعابد السومرية. وقد اتخذ سرگون لنفسه لقب "الكاهن الممسح من آنو" و "إنسي الأكبر لإنليل".[10] وبينما يُنسب لسرگون فضل بناء أول إمبراطورية حقيقية، فإن لگل-زاگى-سي قد سبقه لذلك؛ بعد جاء للحكم في أُمـّة، فقد أخضع أو استولى على أور، أوروك، نيپور ولگش. وقد ادعى لگل-زاگى-سي أنه حكم أراضي بعيدة تصل للبحر المتوسط.[11]

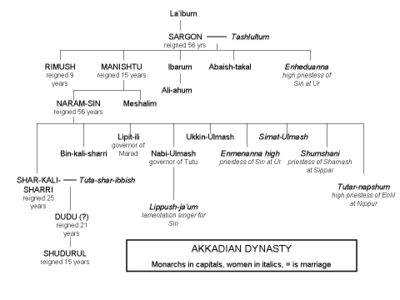

وبينما نسخ مختلفة من قائمة الملوك السومريين تعطي لسرگون فترة حكم 56، 55، أو 54 عاما، فإنه لم يُعثر إلا على وثائق مؤرخة تذكر أربع أسماء سنوات من حكمه. أسماء تلك الأعوام من حكمه تصف حملاته ضد عيلام، ماري، سيمـّوروم (منطقة حورية)، و اوروآ (مدينة-دولة عيلامية).[12] وقد استمرت أسرته الأكادية حاكمة لقرن بعد وفاته.

الحروب في الشمال الغربي والشرق

Shortly after securing Sumer, Sargon embarked on a series of campaigns to subjugate the entire الهلال الخصيب. According to the Chronicle of Early Kings, a later Babylonian historiographical text:

[Sargon] had neither rival nor equal. His splendor, over the lands it diffused. He crossed the sea in the east. In the eleventh year he conquered the western land to its farthest point. He brought it under one authority. He set up his statues there and ferried the west's booty across on barges. He stationed his court officials at intervals of five double hours and ruled in unity the tribes of the lands. He marched to Kazallu and turned Kazallu into a ruin heap, so that there was not even a perch for a bird left.[13]

استولى سرگون على ماري، يرموتي, and Ebla as far as the Cedar Forest (Amanus) and the silver mountain (Taurus). The Akkadian Empire secured trade routes and supplies of wood and precious metals could be safely and freely floated down the Euphrates to Akkad.[14]

وفي الشرق، Sargon defeated an invasion by the four leaders of Elam, led by the king of Awan. Their cities were sacked; the governors, viceroys, and kings of Susa, Barhashe, and neighboring districts became vassals of Akkad, and the Akkadian language became the lingua franca of the entire region. During Sargon's reign, Akkadian was standardized and adapted for use with the cuneiform script previously used in the Sumerian language. A style of calligraphy developed in which text on clay tablets and cylinder seals was arranged amidst scenes of mythology and ritual.[15]

الحكم اللاحق

ملحمة ملك المعارك معروفة من لوح باللغة الأكادية في أرشيف العمارنة؛ وقد عُثر على ترجمات له باللغتين الحيثية والحورية.[16] وتصور توغل سرگون، عميقاً، في قلب الأناضول لحماية التجار الأكاديين والرافديين من exactions of the King of Purushanda (Purshahanda). It is anachronistic, however, portraying the 23rd-century Sargon in a 19th-century milieu; the story is thus probably fictional, though it may have some basis in historical fact.[17] The same text mentions that Sargon crossed the Sea of the West (Mediterranean Sea) and ended up in Kuppara, which some authors have interpreted as the Akkadian word for Keftiu, an ancient locale usually associated with Crete or Cyprus.[18]

Famine and war threatened Sargon's empire during the latter years of his reign. The Chronicle of Early Kings reports that revolts broke out throughout the area under the last years of his overlordship:

Afterward in his [Sargon's] old age all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Akkad; and Sargon went onward to battle and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed. Afterward he attacked the land of Subartu in his might, and they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled that revolt, and defeated them; he accomplished their overthrow, and their widespreading host he destroyed, and he brought their possessions into Akkad. The soil from the trenches of Babylon he removed, and the boundaries of Akkad he made like those of Babylon. But because of the evil which he had committed, the great lord Marduk was angry, and he destroyed his people by famine. From the rising of the sun unto the setting of the sun they opposed him and gave him no rest.[19]

However Oppenheim translates the last sentence as "From the East to the West he [i.e. Marduk] alienated (them) from him and inflicted upon (him as punishment) that he could not rest (in his grave)."[5]

Later literature proposes that the rebellions and other troubles of Sargon's later reign were the result of sacrilegious acts committed by the king. Modern consensus is that the veracity of these claims are impossible to determine, as disasters were virtually always attributed to sacrilege inspiring divine wrath in ancient Mesopotamian literature.[15]

ذكراه

Sargon died, according to the short chronology, around 2215 BC. His empire immediately revolted upon hearing of the king's death. Most of the revolts were put down by his son and successor Rimush, who reigned for nine years and was followed by another of Sargon's sons, Manishtushu (who reigned for 15 years).[20] Sargon was regarded as a model by Mesopotamian kings for some two millennia after his death. The Assyrian and Babylonian kings who based their empires in Mesopotamia saw themselves as the heirs of Sargon's empire. Kings such as Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC) showed great interest in the history of the Sargonid dynasty, and even conducted excavations of Sargon's palaces and those of his successors.[21] Indeed, such later rulers may have been inspired by the king's conquests to embark on their own campaigns throughout the Middle East. The Neo-Assyrian Sargon text challenges his successors thus:

الشعوب ذات الرؤوس السوداء سيطرت عليها وأحكمها، الجبال الشم ذوات الرماح البرونزية دمرتها. I ascended the upper mountains; I burst through the lower mountains. The country of the sea I besieged three times; Dilmun I captured. Unto the great Dur-ilu I went up, I ... I altered ... Whatsoever king shall be exalted after me, ... Let him rule, let him govern the black-headed peoples; mighty mountains with axes of bronze let him destroy; let him ascend the upper mountains, let him break through the lower mountains; the country of the sea let him besiege three times; Dilmun let him capture; To great Dur-ilu let him go up.[22]

وينسب مصدر آخر لسرگون التحدي "والآن، أي ملك يريد أن يسمي نفسه نظيراً لي، وأنا الذي انتصر حيثما اتجهت، فليذهب ليفعل ما فعلت."[23]

الأسرة

اسم الزوجة الرئيسية لسرگون هو تشلولتم كما أن أسماء عدد من أنجاله معروف لنا. فإبنته إنحدوآنا، التي ترعرعت في أواخر القرن 24 وأوائل القرن 23 ق.م.، كانت كاهنة وألـّفت أناشيد طقوسية.[24] العديد من أعمالها، بما فيها تمجيد إينانـّا، استمر استخدامه لقرون تالية.[25] سرگون خلفه ابنه، رموش؛ وبعد وفاة رموش، تولى الحكم ابن آخر لسرگون هو مانيشتوشو. ابنان آخران، شو-إنليل (إيباروم) و Ilaba'is-takal (Abaish-Takal)، معروفان.[26]

من أسباب نجاح سرگون في سياسته، تعيينه لأفراد أسرته في المراكز المهمة، فقد أصبحت ابنته إنحدوأنّا كاهنةً لإله القمر نانّا في أور ولإله السماء آنو في أوروك، وهذه الوظيفة هي من المراكز الدينية المهمة في سومر، وتعد إنحدوأنّا أول شخصية معروفة بالاسم نظمت الشعر بالسومرية، لتقديس إلهة الحب إنانّا وآلهة بلاد الرافدين الأخرى. وقد بقيت عادة ملوك بلاد الرافدين تسمية بناتهم كاهنات لإله القمر حتى عصر نابونيد، ومن أسباب نجاح سياسة شروكين أيضاً إقامته لإدارة مركزية قوية، إضافة إلى وجود جيش قوي.

من أهم القطع الفنية من عصر سرگون نصب النصر، وهو نصب تذكاري عثر على قطع منه في سوسة عاصمة عيلام، وعليه يظهر اسم الملك شروكين وصورته واقفاً على رأس محاربيه مستظلاً بمظلة ويضرب الأسرى داخل الشبكة، وتجري تلك الأحداث أمام الإلهة عشتار المتربعة على عرش.

انظر أيضاً

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الهامش

|

المصادر

- ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- Albright, W. F., A Babylonian Geographical Treatise on Sargon of Akkad's Empire, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1925).

- Alotte De La Fuye, M. Documents présargoniques, Paris, 1908–20.

- Biggs, R.D. Inscriptions from Tell Abu Salabikh, Chicago, 1974.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain, et al. A Companion to the Ancient near East. Blackwell, 2005.

- Botsforth, George W., ed. "The Reign of Sargon". A Source-Book of Ancient History. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

- Cooper, Jerrold S. and Wolfgang Heimpel. "The Sumerian Sargon Legend." Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 103, No. 1, (Jan.-Mar. 1983).

- Deimel, A. Die Inschriften von Fara, Leipzig, 1922–24.

- Diakonov, Igor, 'On the area and population of the Sumerian city-State', VDI (1950), 2, pp. 77–93.

- Frankfort, H. 'Town planning in ancient Mesopotamia', Town Planning Review, 21 (1950), p 104.

- Frayne, Douglas R. "Sargonic and Gutian Period." The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 2. Univ. of Toronto Press, 1993.

- Gadd, C.J. "The Dynasty of Agade and the Gutian Invasion." Cambridge Ancient History, rev. ed., vol. 1, ch. 19. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1963.

- Grayson, Albert Kirk. Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. J. J. Augustin, 1975; Eisenbrauns, 2000.

- Hallo, W. and J. J. A. Van Dijk. The Exaltation of Inanna. Yale Univ. Press, 1968.

- Jestin, R. Tablettes Sumériennes de Shuruppak, Paris, 1937.

- King, L. W., Chronicles Concerning Early Babylonian Kings, II, London, 1907, pp.3ff; 87–96.

- Kramer, S. Noah. History Begins at Sumer: Thirty-Nine "Firsts" in Recorded History. Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 1981.

- Kramer, S. Noah. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture and Character, Chicago, 1963.

- Levin, Yigal. "Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad." Vetus Testementum 52 (2002).

- Lewis, Brian. The Sargon Legend: A Study of the Akkadian Text and the Tale of the Hero Who Was Exposed at Birth. American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series, No. 4. Cambridge, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1984.

- Luckenbill, D. D., On the Opening Lines of the Legend of Sargon, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures (1917).

- MacKenzie, Donald A. Myths of Babylonia and Assyria. Gresham, 1900.

- Nougayrol, J. Revue Archeologique, XLV (1951), pp. 169 ff.

- Oates, John. Babylon. London: Thames and Hudson, 1979.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (translator). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3d ed. James B. Pritchard, ed. Princeton: University Press, 1969.

- Parrot, A. Mari, Capitale Fabuleuse, Paris, 1974.

- Parrot, A. Le temple d'Ishtar, Paris, 1956.

- Parrot, A. Les temples d'Ishtarat et de Ninni-zaza, Paris, 1967.

- Poplicha, Joseph. "The Biblical Nimrod and the Kingdom of Eanna." Journal of the American Oriental Society Vol. 49 (1929), pp. 303–317.

- Postgate, Nichol. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge, 1994.

- Rank, Otto. The Myth of the Birth of the Hero. Vintage Books: New York, 1932.

- Roux, G. Ancient Iraq, London, 1980.

- Sayce, A. H., New Light on the Early History of Bronze, Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (1921).

- Schomp, Virginia . Ancient Mesopotamia. Franklin Watts, 2005.

- Strange, John. "Caphtor/Keftiu: A New Investigation." Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 102, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1982), pp. 395–396

- Sollberger, E. Corpus des Inscriptions 'Royales' Présargoniques de Lagash, Paris, 1956.

- Van der Mieroop, Marc. A History of the Ancient Near East: ca. 3000-323 BC. Blackwell, 2006.

- Van der Mieroop, Marc., Cuneiform Texts and the Writing of History, Routledge, 1999.

- Vandersleyen, Claude. "Keftiu: A Cautionary Note." Oxford Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 22 Issue 2 Page 209 (2003).

- Wainright, G.A. "Asiatic Keftiu." American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 56, No. 4 (Oct., 1952), pp. 196–212.

وصلات خارجية

- Neo-Assyrian Sargon legend

- Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., "The Sargon legend: translation." The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford 1998. [1]

- "Sargon did he exist?"

- Sargon and the Vanishing Sumerians

- Lexicorient article on Sargon

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه اور-زبابا |

ملك كيش ? – 2270 ق.م. (قصير) |

تبعه رموش |

| سبقه لوگل-زاگى-سي |

ملك اوروك، لگش، واومـّا ح. 2270 – 2215 ق.م. (قصير) |

تبعه رموش |

| سبقه لا أحد |

ملك أكاد ح. 2270 – 2215 ق.م. (قصير) |

تبعه رموش |

| سبقه لوح-إشان من أوان |

سيد عيلام ح. 2270 – 2215 ق.م. (قصير) |

تبعه رموش |

| مشاهير حكام سومر | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الملوك قبل الطوفان | ألوليم • دوموزيد الراعي • زيوسودرا | الأسرة الثالثة من كيش | كوبابا |

| الأسرة الأولى من كيش | Etana • Enmebaragesi | الأسرة الثالثة من أوروك | لوگل-زاگى-سي |

| الأسرة الأولى من أوروك | إنمركار • لوگلباندا • دوموزيد الصياد • گلگامش | أسرة أكاد | سرگون • (إنحدوانا)† • رموش • مانيشتوشو • نرم-سن • شر-كالي-شري • دودو • Shu-turul |

| الأسرة الأولى من أور | مسقلمدق* • مشآنىپادا • پوابي* | ||

| الأسرة الثانية من أوروك | Enshakushanna | الأسرة الثانية من لگش | پوزر-ماما • گوديا |

| الأسرة الأولى من لگش | اور-نانشه • إياناتوم • إن-أنا-توم الأول • إنتمنا • أوروكأگينا | الأسرة الخامسة من أوروك | اوتو-حگل |

| أسرة أدب | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | الأسرة الثالثة من اور | اور نـَمـّو • شولگي • أمار-سين • شو-سين • إبي-سين |

| * مسقلمدق وپوابي، بالرغم من أنهما لم يكونا حكاماً، فقد اشتهرا بسبب اللقى في مقبرتيهما.

† إنحدوانا، بالرغم من أنها لم تكن حاكمة، فقد كانت كاهنة اشتهرت بأناشيدها. | |||