شر-كالي-شري

| Shar-Kali-Sharri 𒊬𒂵𒉌 𒈗𒌷 | |

|---|---|

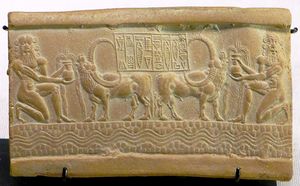

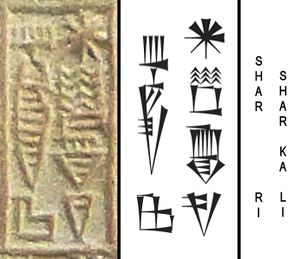

طبع ختم أسطواني من عهد الملك الأكدي شاركاليشاري، بالنقش الأوسط: "المقدس شركاليشرّي أمير أكـَّد، إبني-شرّوم الكاتب خادمه". الجاموس طويل القرن يُعتقد أنه أتى من وادي السند، ويشهد على تبادلات مع ملوخـّا، حضارة وادي السند. حوالي 2217-2193 ق.م. متحف اللوڤر.[1][2][3] | |

| ملك الامبراطورية الأكدية | |

| العهد | ح. 2217 ق.م. – 2193 ق.م. |

| سبقه | نرام-سن |

| تبعه | إگيگي |

| الزوج | Tutasharlibish[4] |

| الأسرة المالكة | أسرة أكـَّد |

| الأب | نرام سن الأكادي |

شـَر-كالي-شرّي (𒊬𒂵𒉌 𒈗𒌷؛ شـَر-گاني-شرّي؛[6] حكم ح. 2217-2193 ق.م. التأريخ المتوسط، ح. 2153-2129 ق.م. التأريخ القصير) هو خامس ملوك الإمبراطورية الأكدية.

حياته

حسب قائمة الملوك السومريين هو ابن الملك نرام سين تولى الحكم في سنة 2218 ق م خلفا لوالده واستمر حكمه لمدة 24 سنة أو 25 سنة إلى حوالي سنة 2100 ق م، كثرت الحروب ضده في من القبائل الكوتية ومن القبائل الامورية و كذلك ضد عيلام , و كذلك قام بإنشاء المعابد في مدن بابل ونيبور لكن بعد ذلك بفترة قصيرة لم يتمكن العلماء متى توفي شار كالي شاري ومن خلفه من ابنائه فقد ظهرت اسماء كإگيگي وإمي ونانوم ويولو فقد حكم هؤلاء الملوك خلال 3 سنوات إلى ان تولى الملك دودو (ملك) والذي حكم لمدة 21 سنة.

Succeeding his father نرام-سن in c. 2217 ق.م.، he came to the throne in an age of increasing troubles. The raids of the Gutian hill peoples of the Zagros mountains that began in his father's reign were becoming more and more frequent, and he was faced with a number of rebellions from vassal kings against the high taxes they were forced to pay to fund the defence against the Gutian threat.[7] Contemporary year-names for Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad indicate that in one unknown year of his reign, he captured Sharlag, king of Gutium, while in another year, "the yoke was imposed on Gutium".[8]

Sumer also suffered from a terrible drought during Shar-Kali-Sharri's reign in about c. 2200 BC, leading to the complete abandonment of some cities. This is complementary to Egyptian records, which suggest there was a drought around the same time during the reign of king Pepi II.[9] After Shar-Kali-Sharri’s death in c. 2193 BC, Sumer fell into anarchy, with no king able to achieve dominance for long.[10] The king list states:

- "Then who was king? Who was not the king? Igigi, Imi, Nanum, Ilulu: four of them ruled for only 3 years."

فقدان لگش

استولى الغريم پوزر-ماما على لگش في عهد شر-كالي-شري، حين تركت المشاكل مع الگوتي الملك السرگوني حاكماً فقط على “دولةٍ عجزٍ صغيرة تتمركز عند التقاء نهري ديالى ودجلة.”[11] وقد أسس پوزر-ماما أسرة لگش الثانية.

Out of the 24 years of his reign, names survive for some 18 of them, and indicate successful campaigns against the Gutians, Amorites, and Elamites, as well as temple construction in Nippur and Babylon.[12] Shar-Kali-Sharri reported defeating the Elamites at Akshak.[13][14]

الذكرى

The next recorded king of Akkad to rule for any reasonable amount of time was دودو, who is said by the king list to have reigned for 21 years. However, by this time the Akkadian empire was no more, and Dudu most likely controlled no more than Akkad itself, meaning Shar-Kali-Sharri was the last Akkadian king to actually have an empire under his control.

In the 1870s, Assyriologists thought Shar-Kali-Sharri was identical with the Sargon of Agade of Assyrian legend, but this identification was recognized as mistaken in the 1910s.[15]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ "Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum". Louvre Museum.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art (in الإنجليزية). Walter de Gruyter. p. 187. ISBN 9781614510352.

- ^ Elisabeth Meier Tetlow (2004). Women, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The ancient Near East. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ BM 1883,0118.700

- ^ تُكتب šar-ka3-li2-šar-ri2 𒊬𒂵𒉌𒊬𒌷 في مخطوطات لاحقة لقائمة الملوك السومريين، ولكن šar-ka3-li2 LUGAL-ri2 𒊬𒂵𒉌 𒈗𒌷 في نقوش ملكية بالرغم من أن علامة LUGAL ("ملك") لم يكن لها القيمة الصوتية šar في السومرية (Laurence Austine Waddell, The Makers of Civilization 1968, p. 529)

- ^ John Haywood (2015-06-04). Chronicles of the Ancient World. Quercus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978 1 84866 896 6.

- ^ Year-names for Sharkalisharri

- ^ John Haywood (2015-06-04). Chronicles of the Ancient World. Quercus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978 1 84866 896 6.

- ^ John Haywood (2015-06-04). Chronicles of the Ancient World. Quercus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978 1 84866 896 6.

- ^ Frayne, Douglas R. (1993). Sargonic and Gutian Periods p. 186, Toronto, Buffalo, London. University of Toronto Press Incorporated

- ^ Year-names of Sharkalisharri

- ^ Carter, Elizabeth; Stolper, Matthew W. (1984). Elam: Surveys of Political History and Archaeology (in الإنجليزية). University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780520099500.

- ^ Potts, D. T. (2015). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. 188. ISBN 9781316586310.

- ^ "But it is now evident that Sharganisharri was 'not confused with Shargani or Sargon' in the 'tradition' (p. 133), but only by the moderns who insisted on connecting the Sharganisharri of contemporary documents with the Sargon of the Legend" D. D. Luckenbill, Review of: The Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria by Morris Jastrow, Jr., The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures Vol. 33, No. 3 (Apr., 1917), pp. 252-254.

| مشاهير حكام سومر | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الملوك قبل الطوفان | ألوليم • دوموزيد الراعي • زيوسودرا | الأسرة الثالثة من كيش | كوبابا |

| الأسرة الأولى من كيش | Etana • Enmebaragesi | الأسرة الثالثة من أوروك | لوگل-زاگى-سي |

| الأسرة الأولى من أوروك | إنمركار • لوگلباندا • دوموزيد الصياد • گلگامش | أسرة أكاد | سرگون • (إنحدوانا)† • رموش • مانيشتوشو • نرم-سن • شر-كالي-شري • دودو • Shu-turul |

| الأسرة الأولى من أور | مسقلمدق* • مشآنىپادا • پوابي* | ||

| الأسرة الثانية من أوروك | Enshakushanna | الأسرة الثانية من لگش | پوزر-ماما • گوديا |

| الأسرة الأولى من لگش | اور-نانشه • إياناتوم • إن-أنا-توم الأول • إنتمنا • أوروكأگينا | الأسرة الخامسة من أوروك | اوتو-حگل |

| أسرة أدب | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | الأسرة الثالثة من اور | اور نـَمـّو • شولگي • أمار-سين • شو-سين • إبي-سين |

| * مسقلمدق وپوابي، بالرغم من أنهما لم يكونا حكاماً، فقد اشتهرا بسبب اللقى في مقبرتيهما.

† إنحدوانا، بالرغم من أنها لم تكن حاكمة، فقد كانت كاهنة اشتهرت بأناشيدها. | |||