شولجي

| شولگي Shulgi 𒀭𒂄𒄀 | |

|---|---|

| |

| ملك الامبراطورية السومرية الجديدة | |

| العهد | ح. 2029 ق.م. – 1982 ق.م. |

| سبقه | أور نمو |

| تبعه | Amar-Sin |

| الأنجال | Amar-Sin, Liwir-Mitashu |

| الأسرة | أسرة أور الثالثة |

| الأب | أور نمو |

(ح. 2094–2046 ق.م.)

NIN-a-ni..................... "his Lady,"

SHUL-GI.................... "Shulgi"

NITAH KALAG ga...... "the mighty man"

LUGAL URIM KI ma... "King of Ur"

LUGAL ki en............... "King of Sumer"

gi ki URI ke................. "and Akkad,"

E a ni.......................... "her Temple"

mu na DU................... "he built"[4]

شولگي (𒀭𒂄𒄀 dŠulgi, formerly read as Dungi) بـاللغة السومرية) هو ثاني ملوك أسرة أور الثالثة بعد والده أور نمو مشرع أول قانون في بلاد الرافدين استمر حكمه لمدة 48 سنة (2029-1982 ق.م.) وهو من أكمل بناء زقورة أور الكبيرة بعد مقتل والده أور نمو بعد احدى المعارك مع الكوتيين.

شولگي هو ابن أور نمو حسب قائمة الملوك السومريين، استمر شولگي بنهج والده بمحاربة الكوتيين، كما قام أيضا باكمال بناء زقورة اور وبنى أيضا معابد وهناك من المصادر تعزى بناء معبد الإله ايساكيلا في بابل للملك شولگي كما أنه قام ببناء مدينة دير بعد طرد الكوتيين منها وبنى عدة معابد كما أنه قام بإنشاء عدة مدن و قرى و شوارع كما يعزى إليه أنه أول من بنى أماكن استراحات او مقاهي في الطرق من اجل الاستراحة.

كما افتخر شولگي بقدرته العدْو بسرعات فائقة لمسافات طويلة. فقد ادعى في العام السابع من حكمه أنه ركض من نيپور إلى أول، وهي مسافة ليس أقل من 160 كيلومتر.[5] ويشير كرامر إلى شولگي بأنه "أول بطل عداء مسافات طويلة."[6]

حياته وعمله

شولگي كان ابن Ur-Nammu king of Ur – according to one later text (CM 48), by a daughter of the former king Utu-hengal of Uruk – and was a member of the Third dynasty of Ur. Year-names are known for all 48 years of his reign, providing a fairly complete contemporary view of the highlights of his career.[7]

Shulgi is best known for his extensive revision of the scribal school's curriculum. Although it is unclear how much he actually wrote, there are numerous praise poems written by and directed towards this ruler. He proclaimed himself a god in his 23rd regnal year.[8]

Some early chronicles castigate Shulgi for his impiety: The Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19)[9] states that "he did not perform his rites to the letter, he defiled his purification rituals". CM 48[10] charges him with improper tampering with the rites, composing "untruthful stelae, insolent writings" on them. The Chronicle of Early Kings (ABC 20)[11] accuses him of "criminal tendencies, and the property of Esagila and Babylon he took away as booty."

الاسم

Early uncertainties about the reading of cuneiform led to the readings "Shulgi" and "Dungi" being common transliterations before the end of the 19th century. However, over the course of the 20th century, the scholarly consensus gravitated away from dun towards shul as the correct pronunciation of the 𒂄 sign. The spelling of Shulgi's name by scribes with the diĝir determinative reflects his deification during his reign, a status and spelling previously claimed by his Akkadian predecessor Naram-Sin.[12]

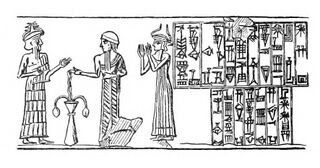

Portraits of Shulgi from his Nuska seal. Louvre Museum

Portrait of Shulgi as a builder, on a foundation nail. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Personal glorification

Shulgi also boasted about his ability to maintain high speeds while running long distances. He claimed in his 7th regnal year to have run from Nippur to Ur, a distance of not less than 100 miles.[5] Kramer refers to Shulgi as "The first long distance running champion."[13]

Shulgi wrote a long royal hymn to glorify himself and his actions, in which he refers to himself as "the king of the four-quarters, the pastor of the black-headed people".[14]

Shulgi claimed that he spoke Elamite as well as he spoke Sumerian.[12]

النزاعات المسلحة

While Der had been one of the cities whose temple affairs Shulgi had directed in the first part of his reign, in his 20th year he claimed that the gods had decided that it now be destroyed, apparently as some punishment. The inscriptions state that he "put its field accounts in order" with the pick-axe. His 18th year-name was Year Liwir-mitashu, the king's daughter, was elevated to the ladyship in Marhashi, referring to a country east of Elam and her dynastic marriage to its king, Libanukshabash. Following this, Shulgi engaged in a period of expansionism at the expense of highlanders such as the Lullubi, and destroyed Simurrum (another mountain tribe) and Lulubum nine times between the 26th and 45th years of his reign.[15] In his 30th year, his daughter was married to the governor of Anshan; in his 34th year, he was already levying a punitive campaign against the place. He also destroyed Kimash and Humurtu (cities to the east of Ur, somewhere in Elam) in the 45th year of his reign.[15] Ultimately, Shulgi was never able to rule any of these distant peoples; at one point, in his 37th year, he was obliged to build a large wall in an attempt to keep them out.[5]

سوسا

(c. 2094–2047 BC)

NIN-a-ni....................... "his Lady,"

DSHUL-GI.................... "Shulgi"

NITAH KALAG ga........ "the mighty man"

LUGAL URIM KI ma..... "King of Ur"

LUGAL kien-................. "King of Sumer"

gi kiURIke..................... "and Akkad,"

nam-ti-la-ni-sze3........... "for his life"

a mu-na-ru................... "dedicated (this)"

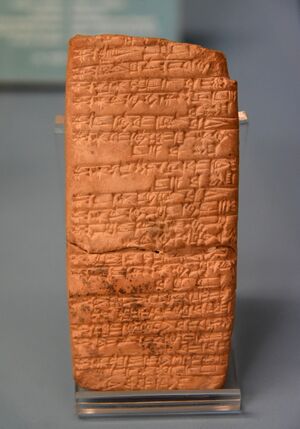

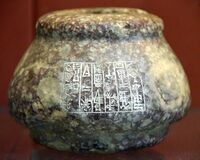

Shulgi is known to have made dedications at Susa, as foundation nails with his name, dedicated to god Inshushinak have been found there.[21] One of the votive foundation nails reads: "The god 'Lord of Susa,' his king, Shulgi, the mighty male, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad, the..., his beloved temple, built.".[22][23][24] An etched carnelian bead, now located in the Louvre Museum (Sb 6627) and inscribed with a dedication by Shulgi was also found in Susa, the inscription reading: "Ningal, his mother, Shulgi, god of his land, King of Ur, King of the four world quarters, for his life dedicated (this)".[25][26][27]

The Ur III dynasty had held control over Susa since the demise of Puzur-Inshushinak, and they built numerous buildings and temples there. This control was continued by Shulgi as shown by his numerous dedications in the city-state.[28] He also engaged in marital alliances, by marrying his daughters to rulers of eastern territories, such as Anšan, Marhashi and Bashime.[28]

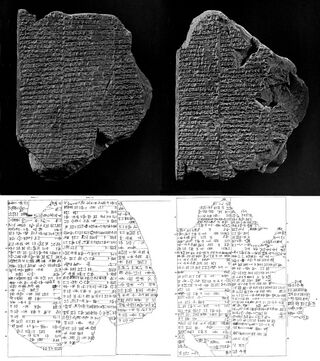

Votive tablet of Shulgi, excavated in Susa: "For the goddess Ninhursag of Susa, his Lady, Shulgi, the great man, King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, built her temple ". Louvre Museum, Sb 2884.[29][30]

Foundation nail dedicated by Shulgi to the Elamite god Inshushinak, found in Susa. Louvre Museum

Carnelian bead with dedicatory inscription by Shulgi, found in Susa. Louvre Museum, Sb 6627

العصرنة

Shulgi apparently led a major modernization of the Third Dynasty of Ur.[12] He improved communications, reorganized the army, reformed the writing system and weight and measures, unified the tax system and created a strong bureaucracy.[12] He also promulgated the law code known as the Code of Ur-Nammu after his father.[12]

أسماء الأعوام

There are extensive remains for the year names of Shulgi, which have been entirely reconstructed from year 1 to year 48. Some of the most important are:[32]

1. Year : Šulgi is king

2. Year: The foundations of the temple of Ningubalag were laid

6. Year: The king straightened out the Nippur road

7. Year: The king made a round trip between Ur and Nippur (in one day)

10. Year: The royal mountain-house (the palace) was built

18. Year: Liwirmittašu, the daughter of the king, was elevated to the queenship of Marhashi

21c. Year: Der was destroyed

24. Year: Karahar was destroyed

25. Year: Simurrum was destroyed

27. Year after: "Šulgi the strong man, the king of the four corners of the universe, destroyed Simurrum for the second time"

27b. Year: "Harszi was destroyed"

30. Year: The governor of Anšan took the king's daughter into marriage

31. Year: Karhar was destroyed for the second time

32. Year: Simurrum was destroyed for the third time

34. Year: Anshan was destroyed

37. Year: The wall of the land was built

42. Year: The king destroyed Šašrum

44. Year: Simurrum and Lullubum were destroyed for the ninth time

45. Year: Šulgi, the strong man, the king of Ur, the king of the four-quarters, smashed the heads of Urbilum, Simurrum, Lullubum and Karhar in a single campaign

46. Year: Šulgi, the strong man, the king of Ur, the king of the four-quarters, destroyed Kimaš, Hurti and their territories in a single day— Main year names of Shulgi[33]

زواجه بأميرة من ماري

Shulgi was a contemporary of the Shakkanakku rulers of Mari, particularly Apil-kin and Iddi-ilum.[34][35] An inscription mentions that Taram-Uram, the daughter of Apil-kin, became the "daughter-in-law" of Ur-Nammu, and therefore the Queen of king Shulgi.[36][37] In the inscription, she called herself "daughter-in-law of Ur-Nammu", and "daughter of Apil-kin, Lugal ("King") of Mari", suggesting for Apil-kin a position as a supreme ruler, and pointing to a marital alliance between Mari and Ur.[38][39]

لقى ونقوش

Lugal Urimkima/ Lugal Kiengi Kiuri 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠𒈠𒈗𒆠𒂗𒄀𒆠𒌵, "King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, on a votive tablet of Shulgi. The final ke4 𒆤 is the composite of -k (genitive case) and -e (ergative case).[40]

Shulgi completed the great Ziggurat of Ur

Earrings inscribed in the name of Shulgi.[41]

Seal of Shulgi, with worshipper and seated deity: "Shulgi, the mighty hero, King of Ur, king of the four regions, Ur-(Pasag?) the scribe, thy servant".[42]

Weight of 1⁄2 mina (actual weight 248 gr.) dedicated by King Shulgi and bearing the emblem of the crescent moon: it was used in the temple of the Moon-God at Ur. Diorite, beginning of the 21st century BC (Ur III). Louvre Museum, Department of Oriental Antiquities, Richelieu, first floor, room 2, case 6

انظر أيضاً

| مشاهير حكام سومر | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الملوك قبل الطوفان | ألوليم • دوموزيد الراعي • زيوسودرا | الأسرة الثالثة من كيش | كوبابا |

| الأسرة الأولى من كيش | Etana • Enmebaragesi | الأسرة الثالثة من أوروك | لوگل-زاگى-سي |

| الأسرة الأولى من أوروك | إنمركار • لوگلباندا • دوموزيد الصياد • گلگامش | أسرة أكاد | سرگون • (إنحدوانا)† • رموش • مانيشتوشو • نرم-سن • شر-كالي-شري • دودو • Shu-turul |

| الأسرة الأولى من أور | مسقلمدق* • مشآنىپادا • پوابي* | ||

| الأسرة الثانية من أوروك | Enshakushanna | الأسرة الثانية من لگش | پوزر-ماما • گوديا |

| الأسرة الأولى من لگش | اور-نانشه • إياناتوم • إن-أنا-توم الأول • إنتمنا • أوروكأگينا | الأسرة الخامسة من أوروك | اوتو-حگل |

| أسرة أدب | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | الأسرة الثالثة من اور | اور نـَمـّو • شولگي • أمار-سين • شو-سين • إبي-سين |

| * مسقلمدق وپوابي، بالرغم من أنهما لم يكونا حكاماً، فقد اشتهرا بسبب اللقى في مقبرتيهما.

† إنحدوانا، بالرغم من أنها لم تكن حاكمة، فقد كانت كاهنة اشتهرت بأناشيدها. | |||

الهامش

- ^ Full transcription: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ "Nimintabba tablet". British Museum.

- ^ Enderwitz, Susanne; Sauer, Rebecca (2015). Communication and Materiality: Written and Unwritten Communication in Pre-Modern Societies (in الإنجليزية). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 28. ISBN 978-3-11-041300-7.

- ^ أ ب "(للإلهة) Nimintabba، سيدته، شولگي الرجل القوي، ملك أور، وملك سومر وأكد، her house, built." in Expedition (in الإنجليزية). University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. 1986. p. 30.

- ^ أ ب ت Hamblin, William J. Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- ^ See his History Begins at Sumer, Chapter 31, "Shulgi of Ur: The First Long-Distance Champion".

- ^ "T6K2.htm". Cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ Van De Mieroop, Marc. (2005). A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000–323 BC, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, p. 76

- ^ "The Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19)". Archived from the original on 28 February 2006.

- ^ "The kings of Ur (CM 48)". Archived from the original on 10 May 2006.

- ^ "Chronicle of early kings (ABC 20)". Archived from the original on 28 February 2006.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDTP132 - ^ See his History Begins at Sumer, Chapter 31, "Shulgi of Ur: The First Long-Distance Champion".

- ^ "I am the king of the four-quarters, I am a shepherd, the pastor of the "black-headed people"" in Liverani, Mario (2013). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-134-75084-9.

- ^ أ ب Samuel Noah Kramer (2010-09-17). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ (RIME 3/2, p. 161-162)

- ^ "DINGIR.NIN.LILA / NIN-A-NI / DINGIR.SHUL.GI / NITA-KALAG.GA / LUGAL URI/ .KI-MA / LUGAL.KI.EN / GI KI-URI3.KI / NAM.TI.LA NI.SHE3/ A MU.NA.RU." Inscription Translation: "To Ninlil, his lady, Shulgi, mighty man, King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, has dedicated (this stone) for the sake of his life." "cylinder seal / bead". British Museum.

- ^ "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ Sb 6627 Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-521-56496-0.

- ^ Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus (in الإنجليزية). Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2003. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1.

- ^ Potts, Professor Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-521-56496-0.

- ^ "CDLI-Found Texts Louvre Museum Sb 2881". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ "Votive Foundation Nails". dla.library.upenn.edu.

- ^ Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. 133, Plate 5.1. ISBN 978-0-521-56496-0.

- ^ Potts, D.T (29 July 1999). The Archaeology of Elam. p. 134, Plate 5.2 Sb 6627. ISBN 9780521564960.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Shulgi perle (color image)". Louvre Museum.

- ^ أ ب Potts, Daniel T. (2012). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (in الإنجليزية). John Wiley & Sons. p. 746. ISBN 978-1-4051-8988-0.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "BnF – L'Aventure des écritures". classes.bnf.fr.

- ^ أ ب "Šulgi Year Names (Ist Ni 00394)". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History (in الإنجليزية). Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- ^ "Šulgi Year Names". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ Unger, Merrill F. (2014). Israel and the Aramaeans of Damascus: A Study in Archaeological Illumination of Bible History (in الإنجليزية). Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-62564-606-4.

- ^ Abusch, I. Tzvi; Noyes, Carol (2001). Proceedings of the XLV Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale: historiography in the cuneiform world (in الإنجليزية). CDL Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-883053-67-3.

- ^ Sharlach, T. M. (2017). An Ox of One's Own: Royal Wives and Religion at the Court of the Third Dynasty of Ur (in الإنجليزية). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-5015-0522-5.

- ^ Eppihimer, Melissa (2019). Exemplars of Kingship: Art, Tradition, and the Legacy of the Akkadians (in الإنجليزية). Oxford University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-19-090303-9.

- ^ Lipiński, Edward (1995). Immigration and Emigration Within the Ancient Near East. Peeters Publishers. p. 187. ISBN 9789068317275.

- ^ CIVIL, Michel (1962). "Un nouveau synchronisme Mari-III e dynastie d'Ur". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 56 (4): 213. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23295098.

- ^ Edzard, Dietz Otto (2003). Sumerian Grammar (in الإنجليزية). BRILL. p. 36. ISBN 978-90-474-0340-1.

- ^ "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ أ ب Ward, William Hayes (1910). The seal cylinders of western Asia. Washington : Carnegie Inst. p. 27.

- ^ أ ب Simo Parpola, Asko Parpola and Robert H. Brunswig, Jr "The Meluḫḫa Village: Evidence of Acculturation of Harappan Traders in Late Third Millennium Mesopotamia?" in Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient Vol. 20, No. 2, 1977, p. 136-137

- ^ "Collections Online British Museum". britishmuseum.org.

وصلات خارجية

- Shulgi's axe sold illegally in Germany from the German Middle East magazine zenith

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Ur-Nammu |

King of Ur, Sumer and Akkad ca. 21st century BCE |

تبعه Amar-Sin |

![Votive tablet of Shulgi, excavated in Susa: "For the goddess Ninhursag of Susa, his Lady, Shulgi, the great man, King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, built her temple ". Louvre Museum, Sb 2884.[29][30]](/w/images/thumb/1/1b/Votive_tablet_of_Shulgi%2C_excavated_in_Susa.jpg/150px-Votive_tablet_of_Shulgi%2C_excavated_in_Susa.jpg)

![Lugal Urimkima/ Lugal Kiengi Kiuri 𒈗𒋀𒀊𒆠𒈠𒈗𒆠𒂗𒄀𒆠𒌵, "King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad, on a votive tablet of Shulgi. The final ke4 𒆤 is the composite of -k (genitive case) and -e (ergative case).[40]](/w/images/thumb/b/b9/Lugal_Urimkima_Lugal_Kiengi_Kiuri%2C_King_of_Ur%2C_King_of_Sumer_and_Akkad%2C_on_a_seal_of_Shulgi_%28transcription%29.jpg/200px-Lugal_Urimkima_Lugal_Kiengi_Kiuri%2C_King_of_Ur%2C_King_of_Sumer_and_Akkad%2C_on_a_seal_of_Shulgi_%28transcription%29.jpg)

![Earrings inscribed in the name of Shulgi.[41]](/w/images/thumb/c/ce/Earrings_from_Shulgi.JPG/200px-Earrings_from_Shulgi.JPG)

![Seal of Shulgi, with Gilgamesh fighting a winged monster: "To Shulgi, son of the king, Ur-dumuzi the scribe, his servant".[42]](/w/images/thumb/d/dc/Seal_of_Shulgi%2C_with_Gilgamesh_fighting_a_winged_monster.jpg/200px-Seal_of_Shulgi%2C_with_Gilgamesh_fighting_a_winged_monster.jpg)

![Seal of Shulgi, with worshipper and seated deity: "Shulgi, the mighty hero, King of Ur, king of the four regions, Ur-(Pasag?) the scribe, thy servant".[42]](/w/images/thumb/f/fb/Seal_of_Shulgi%2C_with_worshipper_and_seated_deity.jpg/200px-Seal_of_Shulgi%2C_with_worshipper_and_seated_deity.jpg)

![A tablet from the period of Shulgi, mentioning the "Meluhha" village in Sumer. British Museum, BM 17751.[43] "Meluhha" (𒈨𒈛𒄩𒆠) actually appears on the beginning of the other side (column II, 1) in the sentence "The granary of the village of Meluhha".[44][43]](/w/images/thumb/7/79/Meluhha_village_tablet_-_BM17751.jpg/142px-Meluhha_village_tablet_-_BM17751.jpg)