حادثة موكدن

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

حادثة موكدن المعروفة أيضًا في اليابان باسم الحادثة المنشورية وفي الصين باسم حادثة 18 سبتمبر وهي حادثة خطط لها الجيش الياباني كذريعة غزو الجزء الشمالي من الصين المعروف بمنشوريا عام 1931.[1][2][3]

On September 18, 1931, Lieutenant Suemori Kawamoto of the Independent Garrison Unit of the 29th Japanese Infantry Regiment (独立守備隊) detonated a small quantity of dynamite[4] close to a railway line owned by Japan's South Manchuria Railway near Mukden (now Shenyang).[5] The explosion was so weak that it failed to destroy the track, and a train passed over it minutes later. The Imperial Japanese Army accused Chinese dissidents of the act and responded with a full invasion that led to the occupation of Manchuria, in which Japan established its puppet state of Manchukuo six months later. The deception was exposed by the Lytton Report of 1932, leading Japan to diplomatic isolation and its March 1933 withdrawal from the League of Nations.[6]

The bombing act is known as the Liutiao Lake Incident (الصينية التقليدية: 柳條湖事變; الصينية المبسطة: 柳条湖事变; پنين: Liǔtiáohú Shìbiàn, Japanese: 柳条湖事件, Ryūjōko-jiken), and the entire episode of events is known in Japan as the Manchurian Incident (Kyūjitai: 滿洲事變, Shinjitai: 満州事変, Manshū-jihen) and in China as the September 18 Incident (الصينية التقليدية: 九一八事變; الصينية المبسطة: 九一八事变; پنين: Jiǔyībā Shìbiàn).

خلفية

Japanese economic presence and political interest in Manchuria had been growing ever since the end of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). The Treaty of Portsmouth that ended the war had granted Japan the lease of the South Manchuria Railway branch (from Changchun to Lüshun) of the China Far East Railway. The Japanese government, however, claimed that this control included all the rights and privileges that China granted to Russia in the 1896 Li–Lobanov Treaty, as enlarged by the Kwantung Lease Agreement of 1898. This included absolute and exclusive administration within the South Manchuria Railway Zone. Japanese railway guards were stationed within the zone to provide security for the trains and tracks; however, these were regular Japanese soldiers, and they frequently carried out maneuvers outside the railway areas.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, the newly formed Chinese government was trying to reassert its authority over the country after over a decade of fragmented warlord dominance. They started to claim that treaties between China and Japan were invalid. China also announced new acts, so the Japanese people (including Koreans and Taiwanese as both regions were under Japanese rule at this time) who settled frontier lands, opened stores or built their own houses in China were expelled without any compensation.[7][8] Manchurian warlord Chang Tso-lin tried to deprive Japanese concessions too, but he was assassinated by the Japanese Kwantung Army. Chang Hsueh-liang, Chang Tso-lin's son and successor, joined the Nanjing Government led by Chiang Kai-shek from anti-Japanese sentiment. Official Japanese objections to the oppression against Japanese nationals within China were rejected by the Chinese authorities.[7][9]

The 1929 Sino-Soviet conflict (July–November) over the Chinese Eastern Railroad (CER) further increased the tensions in the Northeast that would lead to the Mukden Incident. The Soviet Red Army victory over Chang Hsueh-liang's forces not only reasserted Soviet control over the CER in Manchuria but revealed Chinese military weaknesses that Japanese Kwantung Army officers were quick to note.[10]

The Soviet Red Army performance also stunned Japanese officials. Manchuria was central to Japan's East Asia policy. Both the 1921 and 1927 Imperial Eastern Region Conferences reconfirmed Japan's commitment to be the dominant power in Manchuria. The 1929 Red Army victory shook that policy to the core and reopened the Manchurian problem. By 1930, the Kwantung Army realized they faced a Red Army that was only growing stronger. The time to act was drawing near and Japanese plans to conquer the Northeast were accelerated.[11]

In April 1931, a national leadership conference of China was held between Chiang Kai-shek and Chang Hsueh-liang in Nanking. They agreed to put aside their differences and assert China's sovereignty in Manchuria strongly.[12] On the other hand, some officers of the Kwantung Army began to plot to invade Manchuria secretly. There were other officers who wanted to support plotters in Tokyo.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الحادثة

ففي 18 سبتمبر 1931، فجّر الملازم الياباني كاواموتو سيوموري[1] كمية صغيرة من الديناميت بالقرب من سكة حديد تابعة لسكك حديد جنوب منشوريا اليابانية قرب موكدن (الآن شنيانگ).[13] وعلى الرغم من أن الانفجار كان ضعيفًا لدرجة أنه فشل في تحطيم القضبان أمام القطار الذي مرّ بعد دقائق، إلا أن الجيش الإمبراطوري الياباني اتهم المقاومة الصينية مسئولية الحادث.

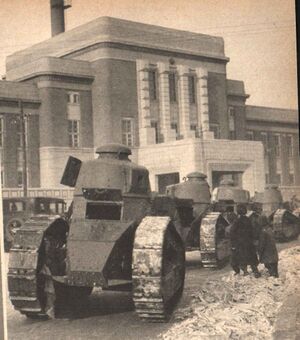

غزو منشوريا

في صباح اليوم التالي (19 سبتمبر)، أتبعته بغزو شامل أدى إلى احتلال منشوريا، والتي أسست فيها اليابان دولة عميلة تحت اسم "مانشوكو" بعد ستة أشهر.

قوبلت الحادثة باستهجان من المجتمع الدولي، مما أدى إلى عزل اليابان دبلوماسيًا وانسحابها من عصبة الأمم.[14]

الأعقاب

جدل

للذكرى

Each year at 10:00 am on 18 September, air-raid sirens sound for several minutes in numerous major cities across China. Provinces include Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Hainan, and others.[15][16]

في الثقافة الشعبية

- The Mukden Incident is depicted in The Adventures of Tintin comic The Blue Lotus, although the book places the bombing near Shanghai. Here it is performed by Japanese agents and the Japanese exaggerate the incident.

- The Chinese patriotic song Along the Songhua River describes the lives of the people who had lost their homeland in Northeast China after the Mukden Incident.

- In Akira Kurosawa's 1946 film No Regrets for Our Youth, the subject of the Mukden Incident is debated.

- See also Junji Kinoshita's play A Japanese Called Otto,[17] which opens with the characters discussing the Mukden Incident.

- The 2010 Japanese anime Night Raid 1931 is a 13-episode spy/pulp series set in 1931 Shanghai and Manchuria. Episode 7, "Incident", specifically covers the Mukden Incident.

- The violent manga Gantz has a reference when an elder says that an occurrence reminds him of the "Manchurian Incident".

- Dutch death metal band Hail of Bullets covers the event in the song "The Mukden Incident" on their 2010 album On Divine Winds, a concept album about the Pacific Ocean theatre of World War II.

- The television drama Kazoku Game (إنگليزية: Family Game) deals with the history textbook controversy in episode 4, mentioning the Mukden Incident.

- The 1969 novel black rain by Masuji Ibuse mentions the incident on numerous occasions.

انظر أيضاً

- False flag

- Huanggutun incident (1928)

- حادثة جينان (1928)

- الحرب الصينية اليابانية الثانية

- الغزو الياباني لمنشوريا (1931)

- حادثة 28 يناير (شانغهاي، 1932)

- الدفاع عن سور الصين العظيم (1933)

- حادثة جسر ماركو پولو (بكين، 1937)

- حادثة گلايڤتس، السياق المتعمـَّد المشابه في غزو پولندا من قِبل ألمانيا النازية

- تاريخ العلاقات الصينية اليابانية#الحرب الصينية اليابانية الثانية والحرب العالمية الثانية

- تاريخ جمهورية الصين

- عسكرية جمهورية الصين

- الجيش الثوري الوطني

المراجع

- ^ أ ب The Cambridge History of Japan: The twentieth century, p.294, Peter Duus,John Whitney Hall, Cambridge University Press, 1989 ISBN 978-0-521-22357-7

- ^ An instinct for war: scenes from the battlefields of history, p.315, Roger J. Spiller, ISBN 978-0-674-01941-6, Harvard University Press

- ^ Concise dictionary of modern Japanese history, p.120, Janet Hunter, University of California Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0-520-04557-6

- ^ The Cambridge History of Japan: The Twentieth Century, p. 294, Peter Duus, John Whitney Hall, Cambridge University Press: 1989. ISBN 978-0-521-22357-7

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan. Chiang Kai-shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf: 2003, p. 202

- ^ Encyclopedia of war crimes and genocide, p. 128, Leslie Alan Horvitz & Christopher Catherwood, Facts on File (2011); ISBN 978-0-8160-8083-0

- ^ أ ب Shin'ichi, Yamamuro (1991). "Manshūkoku no Hou to Seiji: Josetsu" (PDF). The Zinbun Gakuhō : Journal of Humanities. 68: 129–152.

- ^ Shin'ichi Yamamuro (2006). Manchuria Under Japanese Dominion. Translated by Joshua A. Fogel. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 10–13, 21–23. ISBN 978-0-812-23912-6. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ Yamaguchi, Jūji(1967). Kieta Teikoku Manshū. The Mainichi Newspapers Co., Ltd. قالب:ASIN

- ^ Michael M. Walker, The 1929 Sino-Soviet War: The War Nobody Knew (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), p. 290.

- ^ Michael M. Walker, The 1929 Sino-Soviet War: The War Nobody Knew (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017), pp. 290–91.

- ^ Jay Taylor (2009). The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Harvard University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-674-03338-2.

- ^ Fenby, Jonathan. Chiang Kai-shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost. Carroll & Graf Publishers. 2003. pp. 202

- ^ Encyclopedia of war crimes and genocide, p.128, Leslie Alan Horvitz & Christopher Catherwood, Facts on File, 2011, ISBN 978-0-8160-8083-0

- ^ "Sept. 18 Incident marked across China_"中国梦 我的梦"_中国山东网". dream.sdchina.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "我国多个地区拉防空警报纪念九一八事变_新闻中心_新浪网". News.sina.com.cn. Retrieved 2019-03-16.

- ^ Patriots and Traitors: Sorge and Ozaki: A Japanese Cultural Casebook, MerwinAsia: 2009, pp. 101–197

وصلات خارجية

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Articles containing Japanese language text

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2018

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- تاريخ اليابان

- تاريخ جمهورية الصين

- تاريخ منشوريا

- 1931 في الصين

- 1931 في اليابان

- 1932 في الصين

- 1932 في اليابان

- حوادث قتال

- عصبة الأمم

- فترة ما بين الحربين العالميتين

- المشاعر المناهضة لليابان في الصين

- معارك الحرب الصينية اليابانية الثانية

- نزاعات 1931

- نزاعات 1932

- أعمال تخريب