الجيش الثوري الوطني

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

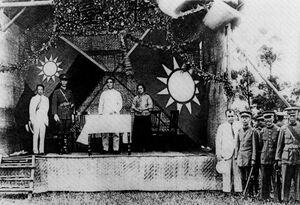

الجيش الثوري الوطني (إنگليزية: National Revolutionary Army؛ NRA)، أحياناً يُختصر إلى الجيش الثوري (革命軍) قبل 1928، وإلى الجيش الوطني (國軍) بعد 1928، كان الذراع العسكري للـكومنتانگ (KMT، أو الحزب الوطني الصيني) من 1925 وحتى 1947 في جمهورية الصين. كما أصبح الجيش النظامي لجمهورية الصين أثناء فترة الكومنتانگ في حكم الحزب التي بدأت في 1928. وقد تغير اسمه إلى القوات المسلحة لجمهورية الصين (中華民國國軍) بعد دستور 1947، الذي نص على السيطرة المدنية على العسكر.

أنشئ في الأصل بمعونة سوڤيتية كوسيلة للكومنتانگ لتوحيد الصين أثناء فترة أمراء الحرب، فخاض الجيش الثوري الوطني اشتباكات كبيرة في التجريدة الشمالية ضد أمراء الحرب الصينيين في جيش بـِيْيانگ، في الحرب الصينية اليابانية الثانية (1937-1945) ضد الجيش الياباني الامبراطوري وفي الحرب الأهلية الصينية ضد جيش التحرير الشعبي.

أثناء الحرب الصينية اليابانية الثانية، the armed forces of the الحزب الشيوعي الصيني were nominally incorporated into the National Revolutionary Army (while retaining separate commands), but broke away to form the People's Liberation Army shortly after the end of the war. With the promulgation of the دستور جمهورية الصين في 1947 and the formal end of the KMT party-state, the الجيش الثوري الوطني تغير اسمه إلى القوات المسلحة لجمهورية الصين (中華民國國軍)، بتشكيل معظم قواته جيش جمهورية الصين، الذي انسحب إلى جزيرة تايوان في 1949.

التاريخ

The NRA was founded by the KMT in 1925 as the military force destined to unite China in the Northern Expedition. Organized with the help of the Comintern and guided under the doctrine of the Three Principles of the People, the distinction among party, state and army was often blurred. A large number of the Army's officers passed through the Whampoa Military Academy, and the first commandant, Chiang Kai-shek, became commander-in-chief of the Army in 1925 before launching the successful Northern Expedition. Other prominent commanders included Du Yuming and Chen Cheng. The end of the Northern Expedition in 1928 is often taken as the date when China's Warlord era ended, though smaller-scale warlord activity continued for years afterwards.

In 1927, after the dissolution of the First United Front between the Nationalists and the Communists, the ruling KMT purged its leftist members and largely eliminated Soviet influence from its ranks. Chiang Kai-shek then turned to Germany, historically a great military power, for the reorganization and modernization of the National Revolutionary Army. The Weimar Republic sent advisers to China, but because of the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles they could not serve in military capacities. Chiang initially requested famous generals such as Ludendorff and von Mackensen as advisers; the Weimar Republic government turned him down, however, fearing that they were too famous, would invite the ire of the Allies and that it would result in the loss of national prestige for such renowned figures to work, essentially, as mercenaries.

Nanjing decade

Immediately following the Northern Expedition, the National Revolutionary Army was bloated and required downsizing and demobilisation: Chiang himself stating that soldiers are like water, capable of both carrying the state, and sinking it. This was reflected in the enormous troop figures with 1,502,000 men under arms, of which only 224,000 came under Chiang's direct control; these, however, were the official figures as Chiang stated later he possessed over 500,000 and Feng Yuxiang who officially possessed 269,000 in reality had 600,000 thus the true figure would likely reach 2,000,000.[1]

During the Northern expedition the KMT formed also formed branch political councils: in theory, subordinate political organs that were under the Central Political councils in Nanjing; in reality these were autonomous political bodies with their own military forces. Feng Yuxiang controlled the Kaifeng council; Yan Xishan the Taiyuan council; whilst the Guangxi clique controlled two: the Wuhan and Beiping; under Li Zongren and Bai Chongxi, respectively. Li Jishen, who was related to the Guangxi clique, loosely controlled the Guangzhou council; and a sixth council in Shenyang was under Zhang Xueliang.[2] Chiang was faced with two options one was to immediately centralise the other to gradually do so, in the spirit of the expedition itself which was to eradicate warlordism and regionalism Chiang chose to immediately centralise the branch councils under the guise of demobilisation systematically reducing the regional troop strength whilst centralising them and building up his own strength.[2] This was done in July 1928 with financial conferences calling for demobilisation and military commanders and political officials echoing the call for demobilisation. Chiang called for the reduction of the army to 65 divisions and gathered political support to begin actively reducing troops counts and centralising the army as well as abolishing the branch councils, this threatened the regional leaders and Li Zongren noted that it was intentionally designed to force the regional leaders into action so Chiang could eliminate them.[3]

Central Plains war

Phase 1

The Guangxi clique rebelled in February 1929 when it fired Lu Diping the governor of Hunan who switched sides and joined Chiang, the Guangxi forces invaded Hunan, however Chiang bribed elements of the army in Wuhan to defect and within 2 months the Guangxi clique was routed, in March the party expelled Bai Chongxi, Li Jishen and Li Zongren and promoted their juniors who sided with Chiang in order to sow dissent within the clique, they later re-grouped and attempted to retake Hunan and Guangdong but were repelled in both provinces.[4][5][6]

Also in May Feng Yuxiang entered the war he was too expelled from the party, once again Chiang bribed his enemy's allies and subordinates Han Fuju and Shi Yousan. Feng's armies were defeated and he fled to Shanxi and announced his retirement from politics, by July Chiang's forces had occupied Luoyang. Having defeated two of his largest enemies Chiang pushed further for demobilisation and announced it would be done by March 1930.[7] This move spurred Feng, Yan and the Guangxi clique to ally to face Chiang as Chiang had taken revenue sources from Yan.[8]

Phase 2

The anti-Chiang coalition had forces totalling 700,000 against Chiang's 300,000. Their plan was to seize Shandong and contain Chiang south of the Long-hai railway and the Beijing-wuhan railway then they would advance along the railway lines seizing Xuzhou and Wuhan whilst southern forces did the same to force a link-up.

The war involved over 1,000,000 of which 300,000 became casualties. Chiang's forces proved themselves capable even when outnumbered routing the southern forces by July, however in the north Chiang's forces were defeated and he himself narrowly avoided capture in June only when the northern forces stopped due to the defeat of the southern forces did the north stabilise. Chiang began negotiations for peace with Zhang as an intermediary however Feng and Yan believing themselves to be on the verge of victory refused. Chiang had utilised the lull in action to gather strength and begin counteroffensives along the railways north aided by the closure of fighting in Bengbu by September Chiang was again closing in on Luoyang and this along with bribes spurred Zhang Xueliang to side with Chiang ending the war.[9]

When Adolf Hitler became Germany's chancellor in 1933 and disavowed the Treaty, the anti-communist Nazi Party and the anti-communist KMT were soon engaged in close cooperation. With Germany training Chinese troops and expanding Chinese infrastructure, while China opened its markets and natural resources to Germany. Max Bauer was the first adviser to China.

In 1934, Gen. Hans von Seeckt, acting as adviser to Chiang, proposed an "80 Division Plan" for reforming the entire Chinese army into 80 divisions of highly trained, well-equipped troops organised along German lines. The plan was never fully realised, as the eternally bickering warlords could not agree upon which divisions were to be merged and disbanded. Furthermore, since embezzlement and fraud were commonplace, especially in understrength divisions (the state of most of the divisions), reforming the military structure would threaten divisional commanders' "take". Therefore, by July 1937 only eight infantry divisions had completed reorganization and training. These were the 3rd, 6th, 9th, 14th, 36th, 87th, 88th, and the Training Division.

Another German general, Alexander von Falkenhausen, came to China in 1934 to help reform the army.[10] However, because of Nazi Germany's later cooperation with the Empire of Japan, he was later recalled in 1937.

Second Sino-Japanese war

For a time, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Communist forces fought as a nominal part of the National Revolutionary Army, forming the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army units, but this co-operation later fell apart. Women were also part of the army's corps during the war. In 1937 Soong Mei-ling encouraged women to support the Second Sino-Japanese War effort, by forming battalions, such as the Guangxi Women's Battalion.[11][12]

Troops in India and Burma during World War II included the Chinese Expeditionary Force (Burma), the Chinese Army in India called X Force, and Chinese Expeditionary Force in Yunnan, called Y Force.[13]

The US government repeatedly threatened to cut off aid to China during World War 2 unless they handed over total command of all Chinese military forces to the US. After considerable stalling, the arrangement only fell through due to a particularly insulting letter from the Americans to Chiang.[14] By the end of the war, US influence over the political, economic, and military affairs of China were greater than any foreign power in the last century, with American personnel appointed in every field, such as the Chief of Staff of the Chinese military, management of the Chinese War Production Board and Board of Transport, trainers of the secret police, and Chiang's personal advisor. Sir George Sansom, British envoy to the US, reported that many US military officers saw US monopoly on Far Eastern trade as a rightful reward for fighting the Pacific war,[15] a sentiment echoed by US elected officials.[16]

After the drafting and implementation of the Constitution of the Republic of China in 1947, the National Revolutionary Army was transformed into the ground service branch of the Republic of China Armed Forces – the Republic of China Army (ROCA).[17]

الرتب

Commissioned officer ranks

The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General officers | Senior commissioned officers | Junior commissioned officers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1929[18] | ||||||||||||

| 1929-1936[18] | ||||||||||||

| 1936-1946[19][20] | ||||||||||||

| Title | 特級上將 Tèjí shàngjiàng |

一級上將 Yījí shàngjiàng |

二級上將 Èrjí shàngjiàng |

中將 Zhōngjiàng |

少將 Shàojiàng |

上校 Shàngxiào |

中校 Zhōngxiào |

少校 Shàoxiào |

上尉 Shàngwèi |

中尉 Zhōngwèi |

少尉 Shàowèi |

准尉 Zhǔnwèi |

Other ranks

The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Non-commissioned officers | Soldiers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1929[18] | ||||||

| 1929-1936[18] | ||||||

| 1936-1946[20] | ||||||

| Title | 上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

一等兵 Yīděngbīng |

二等兵 Èrděngbīng |

الفرق التي ترعاها أمريكا

Y-Force

T.V. Soong at the behest of Chiang negotiated US sponsorship of 30 Chinese divisions which were to be designated assault divisions due to the fall of Burma. This plan was adopted concurrently with Y-Force which was the Chinese army in Burma.[21] The divisions of Y-Force were similar to the 1942 divisions’ organisation. With the addition of extra staff especially in communications as well as an anti-tank rifle squad with 2 anti-tank rifles, radios were issued as were bren guns with the number of mortars raised form 36 to 54 to accommodate the lack of heavy artillery. The demands of the Chinese Military Affairs Commission to add additional support staff and divisional artillery were all rejected by the Americans and the idea of a centralised Y-force with the 30 divisions being grouped together was never realised. General Chen Cheng commanded the largest contingent of 15 divisions, Long Yun commanded 5 and 9 under Chiang himself.[21] Prior to the Salween offensive each division was allotted 36 bazookas though actual numbers ran below requirements and rockets were in short supply.[22]

| Army | Old Strength | New Strength | Actual Strength | Reinforcements

en route |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese expeditionary Force(Chen Cheng) | ||||

| XI Group Army | 107,200 | 124,300 | 55,550 | 49,000 |

| XX Group Army | 56,400 | 61,100 | 30,600 | 15,000 |

| Total | 163,600 | 185,400 | 86,100 | 64,000 |

| Yunnan-Indochina Force(Long Yun) | ||||

| I Group Army | 20,400 | 20,400 | 15,650 | 4,650 |

| IX Group Army | 56,400 | 71,400 | 18,400 | 9,290 |

| Total | 66,800 | 91,800 | 34,050 | 13,940 |

| Reserve Army(Chiang) | ||||

| V Group Army | 125,200 | 131,220 | 86,785 | 37,269 |

| Grand Total | 355,600 | 408,420 | 206,935 | 115,209 |

The Chinese army due to sustained combat was grossly under-strength and whilst Chiang promised over 110,000 additional reinforcements. Further reinforcements after this were not forthcoming due to ongoing combat. Nonetheless, Y-Force grew to over 300,000 men with rifles, mortars and machine guns in abundance.[22]

A Y-force division contained 10,790 officers and men with 4,174 rifles, 270 submachine guns, 270 light machine guns, 54 medium machine guns. 27 AT rifles, 36 bazookas, 81 60mm mortars and 30 82mm mortars this was a large improvement over the 1942 division especially in terms of equipment with some divisions additionally receiving Anti-tank companies with guns ranging from 20-47mm. The army troops of a Y-force army contained over 3,000 horses and mules and 16 trucks with 8,404 officers and men with 21 additional machine guns and an artillery battalion with 12 guns and an anti-tank battalion with 4 guns though due to supply limitations over The Hump artillery and anti-tank weaponry did not arrive in large quantities until late 1943 and early 1944.[23]

30 Division Force

General Stilwell envisioned a 90 division strong regular army the first 30 divisions being the aforementioned Y-Force which would re-open the Burma road which would allow for the formation of the next 30 divisions via direct supply delivery. The remaining 30 divisions would be garrison divisions with a reduced force the remainder of the Chinese army would be gradually demobilised or used to fill out the new forces and act as replacements to save resources and supplies. In July 1943 the US War Department agreed to equip the first 30 divisions and 10% of the second batch to facilitate its training which was to be named Z-Force. Stilwell wished to consolidate the existing forces in east China into 30 divisions per the plan but was rebuffed by the Chinese who wanted the lend lease to be used by existing forces. Stilwell persisted and proposed again his 90 division plan with an additional 1-2 armoured divisions with all forces to be ready assuming the opening of the Burma road by January 1945. However, after the Cairo conference the British and Americans did not agree to an amphibious landing in Burma to support an offensive by Y-Force so the plan was dropped as the Burma road would not be opened anytime soon as long as the Japanese remained there.[24]

| Army

(with 3 divisions) |

Strength | %

equipped |

Combat

efficiency |

Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New 1st Army | 43,231 | 100% | Excellent | Gaoling,Guangxi |

| 2nd Army | 23,545 | 100% | Satisfactory | Baoshan, Yunnan |

| 5th Army | 35,528 | 88% | Satisfactory | Kunming, Yunnan |

| New 6th Army | 43,519 | 100% | Excellent | Zhijiang, Hubei |

| 8th Army | 34,942 | 93% | Satisfactory | Bose, Guangxi |

| 13th Army | 30,677 | 88% | Satisfactory | Lipu, Guangxi |

| 18th Army | 30,106 | 99% | Very Satisfactory | Yuanling, Hunan |

| 53rd Army | 34,465 | 30% | Unknown | Midu, Yunnan |

| 54th Army | 31,285 | 100% | Satisfactory | Wunming, Guangxi |

| 71st Army | 30,547 | 96% | Very Satisfactory | Liuzhou, Guangxi |

| 73rd Army | 28,963 | 100% | Satisfactory | Xinhua, Hunan |

| 74th Army | 32,166 | 100% | Very satisfactory | Shanshuwan, Sichuan |

| 94th Army | 37,531 | 79% | Very Satisfactory | Guilin, Guangxi |

| Total | 436,505 |

الموردون الأجانب

بلجيكا

بلجيكا كندا

كندا تشيكوسلوڤاكيا

تشيكوسلوڤاكيا الدنمارك

الدنمارك الجمهورية الفرنسية الثالثة

الجمهورية الفرنسية الثالثة ألمانيا النازية

ألمانيا النازية مملكة إيطاليا

مملكة إيطاليا الاتحاد السوڤيتي

الاتحاد السوڤيتي السويد

السويد المملكة المتحدة

المملكة المتحدة الولايات المتحدة

الولايات المتحدة

انظر أيضاً

- List of German-trained divisions of the National Revolutionary Army

- التعاون الألماني الصيني حتى 1941

- تاريخ جمهورية الصين

- دوگلاس مكارثر

الهامش

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (2003). War and nationalism in China, 1925-1945. RoutledgeCurzon studies in the modern history of Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-415-14571-8.

- ^ أ ب Van de Ven, Hans J. (2003). War and nationalism in China, 1925-1945. RoutledgeCurzon studies in the modern history of Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-415-14571-8.

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (2003). War and nationalism in China, 1925-1945. RoutledgeCurzon studies in the modern history of Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 134–137. ISBN 978-0-415-14571-8.

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (2003). War and nationalism in China, 1925-1945. RoutledgeCurzon studies in the modern history of Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-14571-8.

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The bitter peace: conflict in China 1928-37. Gloucester, UK: Amberley. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-1-4456-5192-7.

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The bitter peace: conflict in China 1928-37. Gloucester, UK: Amberley. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-4456-5192-7.

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. (2017). The bitter peace: conflict in China 1928-37. Gloucester, UK: Amberley. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-1-4456-5192-7.

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (2003). War and nationalism in China, 1925-1945. RoutledgeCurzon studies in the modern history of Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-415-14571-8.

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (2003). War and nationalism in China, 1925-1945. RoutledgeCurzon studies in the modern history of Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-415-14571-8.

- ^ Liang, Hsi-Huey (1978). The Sino-German Connection: Alexander Von Falkenhausen Between China and Germany 1900-1941 (in الإنجليزية). Van Gorcum. ISBN 9789023215547.

- ^ Chung, Mary Keng Mun (2005). Chinese Women in Christian Ministry: An Intercultural Study (in الإنجليزية). Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-5198-5.

- ^ Women of China (in الإنجليزية). Foreign Language Press. 2001.

- ^ See for example Charles F. Romanus and Riley Sunderland, [1]United States Army in World War II: China-Burma-India Theater, United States Army, 1952

- ^ Taylor, Jay. 2009. The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts ISBN 978-0-674-03338-2, pp. 277-292

- ^ Lanxin Xiang (1995). Recasting the Imperial Far East: Britain and America in China, 1945-1950. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 23–24. ISBN 1563244608.

- ^ Michael L. Krenn (1998). Race and U.S. Foreign Policy from 1900 Through World War II. Taylor and Francis. p. 171-172, 347. ISBN 9780815329572.

- ^ "National Revolutionary Army Summary – China's Military in WWII". Totally History (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ^ أ ب ت ث 吳尚融 (2018). 中國百年陸軍軍服1905~2018. Taiwan, ROC: 金剛出版事業有限公司. p. 154. ISBN 978-986-97216-1-5.

- ^ DI (15 June 2015). "World War 2 Allied Officers Rank Insignia". Daily Infographics. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ أ ب Mollo 2001, p. 192.

- ^ أ ب ت Ness, Leland S.; Shih, Bin (2016). Kangzhan: guide to Chinese ground forces 1937-1945. Solihull, West Midlands, England: Helion & Company. pp. 160–165. ISBN 978-1-910294-42-0.

- ^ أ ب Ness, Leland S.; Shih, Bin (2016). Kangzhan: guide to Chinese ground forces 1937-1945. Solihull, West Midlands, England: Helion & Company. pp. 165–170. ISBN 978-1-910294-42-0.

- ^ Ness, Leland (2016). Kangzhan Guide to Chinese Ground Forces 1937-45. Helion. pp. 169–174. ISBN 9781912174461.

- ^ أ ب Ness, Leland (2016). Kangzhan Guide to Chinese Ground Forces 1937–45. Helion. pp. 175–186. ISBN 9781912174461.

وصلات خارجية

- ROC Ministry of National Defense Official Website

- The Armed Forces Museum of ROC

- Information and pictures of Nationalist Revolutionary Army weapons and equipment

- rare pictures of NRA heavy armory

- more pictures of NRA

| هذه المقالة تحتوي على نصوص بالصينية. بدون دعم الإظهار المناسب, فقد ترى علامات استفهام ومربعات أو رموز أخرى بدلاً من الحروف الصينية. |

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- الجيش الثوري الوطني

- عسكرية جمهورية الصين

- كومنتانگ

- التاريخ العسكري لجمهورية الصين

- أجنحة عسكرية لأحزاب

- Military units and formations established in 1925

- تأسيسات 1925 في الصين

- عقد 1920 في الصين

- عقد 1930 في الصين

- عقد 1940 في الصين

- انحلالات 1947

- انحلالات عقد 1940 في الصين

- جيوش منحلة