تيتانيوم

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| صفات عامة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الإسم, الرقم, الرمز | تيتانيوم, Ti, 22 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سلاسل كيميائية | فلزات انتقالية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المجموعة, الدورة, المستوى الفرعي | d , 4 , 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المظهر | معدني فضي

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| كتلة ذرية | 47.867(1) g/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| شكل إلكتروني | [Ar] 3d2 4s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| عدد الإلكترونات لكل مستوى | 2, 8, 10, 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| خواص فيزيائية | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحالة | صلب | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| كثافة عندح.غ. | 4.506 ج/سم³ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| كثافة السائل عند m.p. | 4.11 ج/سم³ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نقطة الإنصهار | 1941 ك 1668 م ° 3034 ف ° | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نقطة الغليان | 3560 ك 3287 م ° 5949 ف ° | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حرارة الإنصهار | kJ/mol 14.15 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حرارة التبخر | kJ/mol 425 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| السعة الحرارية | (25 25.060 C (م) ° ( J/(mol·K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الخواص الذرية | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| البنية البللورية | سداسي | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حالة التأكسد | 2, 3, 4 (اوكسيد متردد) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سالبية كهربية | 1.54 (مقياس باولنج) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| طاقة التأين (المزيد) |

1st: 658.8 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 1309.8 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 2652.5 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف قطر ذري | 140 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف قطر ذري (حسابيا) | 176 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف القطر التساهمي | 136 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| متفرقة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الترتيب المغناطيسي | ??? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| مقاومة كهربية | 20 °C 0.420 µΩ·m | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| توصيل حراري | (300 K ك ) 21.9 (W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تمدد حراري | (25 °C) 8.6 µm/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سرعة الصوت (قضيب رفيع) | (ح.غ.) 5090 م/ث | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| معامل يونج | 116 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| معامل القص | 44 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| معاير الحجم | 110 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نسبة بواسون | 0.32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| صلابة موس | 6.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم فيكرز للصلادة | 970 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم برينل للصلادة | 716 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم التسجيل | 7440-32-6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| النظائر المهمة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المراجع | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

تيتانيوم هو عنصر كيميائي في الجدول الدوري ورمزه Ti ووزنه الذري 22. فلز انتقالي خفيف الوزن، قوي، ذو لمعان ومقاوم للصدأ (بما فيه ماء البحر والكلور)، ولونه معدني أبيض فضي.

ويستخدم التيتانيوم في السبائك القوية خفيفة الوزن (وخصوصاً مع الحديد والألومنيوم) وأكثر مركباته شيوعاً هي ثاني أكسيد التيتانيوم، والذي يستعمل في الصبغات البيضاء. ومن استخدامات تلك الصبغات البيضاء: سائل تصحيح الطباعة الأبيض Correction fluid والبويات البيضاء. ويستخدم كذلك في معجون الأسنان، علامات الطريق البيضاء، وفي الألعاب النارية البيضاء اللون.

التيتانيوم عنصر كيميائي رمزه Ti. وهو فلز خفيف الوزن لونه رمادي فضي. وعدده الذرّي 22، ووزنه الذرّي 47,867. تقع كثافة التيتانيوم بين كثافة الألومنيوم وكثافة الفولاذ الذي لا يصدأ، وينصهر عند 1667°م (+10°م) ويغلي عند 3287°م. يقاوم التيتانيوم التآكل أو الصدأ الناتج عن مياه البحر أو هواء البحر مثله في ذلك مثل البلاتين. وفي هذه الخاصية يفوق الفولاذ الذي لا يصدأ. ولا تؤثر الحموض أو القلويات عالية التآكل على التيتانيوم. وهو فلز قابل للطرق، وله معدل قوة ـ وزن أعلى من الفولاذ. وجميع هذه الصفات تجعل منه فلزًا ذا أهمية كبرى.

الاستخدامات

كان أول استخدام تجاري للتيتانيوم هو استخدامه في شكل أكسيد بديلاً للرصاص الأبيض في الدهانات. يتم إنتاج ثاني أكسيد التيتانيوم أو التيتانيوم المخلوط بالأكسجين كلون صبغي أبيض ذي قوة عالية لتغطية الأسطح أثناء الدهان. كما يُستخدم ثاني أكسيد التيتانيوم في صناعة أغطية الأرضيات والورق والبلاستيك وطلاء الصيني والمطاط وقضبان اللِّحام. أما تيتانات الباريوم، وهو مركب من الباريوم والتيتانيوم، فيمكن استخدامه كبديل للبلورات في أجهزة التلفاز والرادار والميكرفونات وأجهزة التسجيل. وتُصنع جواهر التيتانيا من بلورات أكسيد التيتانيوم. وعند قطعها وصقلها، فإن التيتانيا تصبح أكثر لمعانًا من الماس؛ وإن كانت ليست في صلابته. وقد تم استخدام ثالث كلوريد التيتانيوم أو التيتانيوم الممزوج بالكلور في عمل الستائر الدخانية وكنقطة بدء لصناعة المعادن.

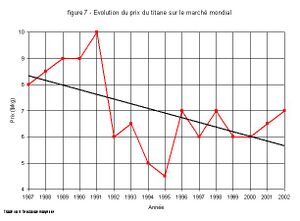

ويعمل فلز التيتانيوم كعنصر سبك مهم. تستخدم القوات المسلحة كميات هائلة من التيتانيوم في الطائرات والمحركات النفاثة لأنها قوية وخفيفة. وهو يستطيع كذلك مقاومة درجات الحرارة حتى درجة 427°م و التي تجعل منه فلزًا مفيدًا في أنواع متعددة من الآليات. وبسبب خصائصه العالية، فإن للتيتانيوم عدداً من الاستخدامات المحتملة مثل الألواح المدرعة للسفن وريش التربينة البخارية، والأجهزة الجراحية والأدوات. وسوف تستخدم صناعة النقل كميات هائلة من التيتانيوم في الحافلات وقطارات السكك الحديدية والسيارات، إذا خُفِّض سعر التيتانيوم بحيث ينافس سعر الفولاذ الذي لا يصدأ.

مناطق وجود الخام

تأتي مرتبة التيتانيوم كتاسع عنصر وفير. ولكن صعوبة استخراج الفلز تجعله مرتفع التكلفة. فلم يحدث مطلقًا أن وجد التيتانيوم في حالة نقية. فهو يوجد في الإيلمنيت أو الروتايل. ويمكن أن يوجد كذلك في المجنيتيت التيتانومي، والتيتنايت والحديد. انظر : الإيلمنيت؛ الروتايل؛ التيتانومي، الخام.

من الدول الرئيسية المنتجة للتيتانيوم أستراليا والصين والهند وكندا وجنوب إفريقيا وماليزيا والنرويج والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ويوجد في كل من أوكرانيا وروسيا كذلك كميات كبيرة من رواسب التيتانيوم، إلا أن أرقام الإنتاج غير متوافرة.

ويعد التيتانيوم أول عناصر المعادن الانتقالية، ويتمتع بالتشكيل الإلكتروني Ar]3d24S2]. وللتيتانيوم خمسة نظائر طبيعية كتلها الذرية محصورة بين (46) و(50) كما أن له ثلاثة نظائر اصطناعية كتلها الذرية (43 و44 و45).

التيتانيوم من العناصر الواسعة الانتشار في الطبيعة، ويأتي في المرتبة الرابعة بعد الألمنيوم والحديد والمغنيزيوم إذ تبلغ نسبته في القشرة الأرضية

نحو 0.63% وزناً.

اكتُشِف التيتانيوم من فلزه المعروف باسم إلِمينيت Elminite عام (1790) من قبل العالم الإنكليزي وليم غريغور William Gregor كما اكتشف من فلزه المعروف باسم روتيل Rutile عام (1794) من قبل العالم الألماني كلابروث Klaproth وسُمي من قبل هذا الأخير بالتيتانيوم تيمناً بأبناء التيتان (أبناء الأرض) في الأساطير اليونانية.

يعد الإلمينيت FeTiO3 والروتيل TiO2 من أهم فلزات التيتانيوم، وهما منتشران في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية وكندا والهند وأسترالية والنرويج وغيرها من الدول، وتنحصر أهمية هذه الفلزات في تحضير معدن التيتانيوم وأكسيده وخلائط التيتانيوم مع الحديد.

التاريخ

اكتشف القس الجيولوجي الإنجليزي وليام گريگور التيتانيوم عام 1791، كـinclusion of a mineral in Cornwall, Great Britain.[1] Gregor recognized the presence of a new element in ilmenite[2] when he found black sand by a stream and noticed the sand was attracted by a magnet.[1] Analyzing the sand, he determined the presence of two metal oxides: iron oxide (explaining the attraction to the magnet) and 45.25% of a white metallic oxide he could not identify.[3] Realizing that the unidentified oxide contained a metal that did not match any known element, in 1791 Gregor reported his findings in both German and French science journals: Crell's Annalen and Observations et Mémoires sur la Physique.[1][4][5] He named this oxide manaccanite.[6]

Around the same time, Franz-Joseph Müller von Reichenstein produced a similar substance, but could not identify it.[2] The oxide was independently rediscovered in 1795 by Prussian chemist Martin Heinrich Klaproth in rutile from Boinik (the German name of Bajmócska), a village in Hungary (now Bojničky in Slovakia).[1][أ] Klaproth found that it contained a new element and named it for the Titans of Greek mythology.[8] After hearing about Gregor's earlier discovery, he obtained a sample of manaccanite and confirmed that it contained titanium.[9]

The currently known processes for extracting titanium from its various ores are laborious and costly; it is not possible to reduce the ore by heating with carbon (as in iron smelting) because titanium combines with the carbon to produce titanium carbide.[1] Pure metallic titanium (99.9%) was first prepared in 1910 by Matthew A. Hunter at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute by heating TiCl4 with sodium at 700–800 °C (1،292–1،472 °F) under great pressure[10] in a batch process known as the Hunter process.[11] Titanium metal was not used outside the laboratory until 1932 when William Justin Kroll produced it by reducing titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) with calcium.[12] Eight years later he refined this process with magnesium and with sodium in what became known as the Kroll process.[12] Although research continues to seek cheaper and more efficient routes, such as the FFC Cambridge process, the Kroll process is still predominantly used for commercial production.[11][2]

Titanium of very high purity was made in small quantities when Anton Eduard van Arkel and Jan Hendrik de Boer discovered the iodide process in 1925, by reacting with iodine and decomposing the formed vapors over a hot filament to pure metal.[13]

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet Union pioneered the use of titanium in military and submarine applications[10] (Alfa class and Mike class)[14] as part of programs related to the Cold War.[15] Starting in the early 1950s, titanium came into use extensively in military aviation, particularly in high-performance jets, starting with aircraft such as the F-100 Super Sabre and Lockheed A-12 and SR-71.[16]

Throughout the Cold War period, titanium was considered a strategic material by the U.S. government, and a large stockpile of titanium sponge (a porous form of the pure metal) was maintained by the Defense National Stockpile Center, until the stockpile was dispersed in the 2000s.[17] As of 2021, the four leading producers of titanium sponge were China (52%), Japan (24%), Russia (16%) and Kazakhstan (7%).[18]

وفي الوقت الحاضر لا زال الإنتاج منخفضًا بسبب صعوبة وتكلفة فصل التيتانيوم عن الخام الذي يوجد به. وتُصنِّع الولايات المتحدة معظم الفلز المكرّر. وتنتج اليابان وبريطانيا كذلك التيتانيوم. وما زالت الأبحاث جارية لزيادة توريده وتقليل تكلفته.

التحضير

طريقة تحضير التيتانيوم حديثة العهد، فهي لذلك تعاني صعوبات جمة تكمن في فصله عن فلزاته، ويتم تحضيره على نطاق ضيق وفي عدد محدود من الدول؛ ولا يمكن الاعتماد على الطريقة التقليدية بإرجاع ثاني أكسيد التيتانيوم بالكربون لتعذر الحصول عليه نقياً من جهة وبسبب تشكل كربيد التيتانيوم من جهة أخرى.

تتبع الولايات المتحدة في تحضير التيتانيوم الطريقة المشتقة من طريقة كرول Kroll المكتشفة عام (1932) والتي طُبقت بصورة فعلية بدءاً من عام (1950)، وأساس هذه الطريقة إرجاع رباعي كلوريد التيتانيوم TiCl4 بمعدن ذي صفة إرجاعية قوية وبالحرارة، وللحصول على رباعي كلوريد التيتانيوم يجب إمرار غاز الكلور على أكسيد التيتانيوم TiO2 المسخن مع الكربون لدرجة 900 ْس في وعاء خاص ثم تكثيف رباعي كلوريد التيتانيوم المتشكل وتنقيته:

يُرجع رباعي الكلوريد الناتج بعد ذلك بمعدن المغنيزيوم المصهور في الدرجة 800 ْس في مفاعل من الفولاذ الطري وتحت الضغط الجوي وبوجود الأرغون أو الهليوم، إذ إن التيتانيوم شره جداً للأكسجين في شروط كهذه:

وينبغي استخراج كلوريد المغنزيوم المصهور من المفاعل عندما يستهلك 60% تقريباً من معدن المغنيزيوم لكي يسمح لبخار كلوريد التيتانيوم بمواصلة التأثير في المغنيزيوم حتى تصبح نسبة المغنيزيوم المتفاعل 85%؛ ويجب أخذ الحيطة والحذر في التفاعل السابق ومنع حدوث أي تفاعل لاحق يؤدي لاختفاء التيتانيوم وفق التفاعلات الآتية:

يمكن إخراج الجزء الصلب من المفاعل بعد التبريد بتكسيره ميكانيكياً، ويستخرج المغنزيوم وكلوريده بعملية غسل للقطع المكسرة بحمض ممدد، كما يمكن عزل المغنزيوم وكلوريده عن التيتانيوم في المفاعل بالتقطير في الخلاء.

قد يكون الإرجاع بالصوديوم المصهور من أكثر الطرق استعمالاً للحصول على التيتانيوم:

ويمكن الحصول على التيتانيوم النقي جداً بتفكيك رباعي يوديد التيتانيوم على سلك مسخن وبمعزل عن الهواء.

خواصه الفيزيائية والكيميائية

التيتانيوم معدن رمادي اللون، لماع، يخضع لتحول تآصلي allotropique في الدرجة 880 ْس تقريباً إذ يمر من الطور a ذي البنية السداسية المكتنزة إلى الطور b ذي البنية المكعبة المركزية. ينصهر بدرجة 1668 ْس تقريباً ويغلي بدرجة 3260 ْس، ويشبه بخواصه السيليسيوم. وهو أخف من الحديد (كثافته 3.34) وأكثر قساوة من الألمنيوم وأكثر مقاومة للتآكل من البلاتين، ويمتاز بصغر تمدده الحراري وبمقاومته الميكانيكية العالية. وهو معدن قابل للطرق وللسحب، ويمكن مقارنة خواصه الميكانيكية الصناعية مع خواص الفولاذ وإن كان التعامل مع التيتانيوم صعباً بسبب امتصاصه الآزوت والأكسجين.

استعماله

يستعمل في صناعة الطائرات ذات السرعات الكبيرة وفي صناعة السفن والصواريخ ومحركات الاحتراق الداخلي، ويستخدم في مختبرات البحث العلمي والصناعات الكيماوية نظراً لمقاومته الكبيرة للتآكل من قبل الكلور وحمض الكروم.

ومع أن التيتانيوم يقاوم معظم المؤثرات الكيمياوية (باستثناء حمض فلور الماء) إلا أنه يبدي ألفة تجاه الهدروجين والهالوجينات والآزوت والأكسجين والكربون والكبريت بارتفاع درجة الحرارة.

مركباته

يكون التيتانيوم في معظم مركباته رباعي التكافؤ، أما مركباته التي يكون فيها ثنائي أو ثلاثي التكافؤ فإنها تتأكسد بسرعة بالهواء ومع ذلك يمكن للتيتانيوم الثلاثي أن يوجد في المحاليل المائية بشكل شاردة معقدة TiH2(O)6]+3] بنفسجية اللون. ومن مركبات التيتانيوم الثلاثي التكافؤ ثلاثي كلوريد التيتانيوم TiCl3 الذي يحضّر بإرجاع كلوريد التيتانيوم بالهدروجين وبدرجة حرارة تراوح بين 500 ْس-1200 ْس، ومن مركبات التيتانيوم الثلاثي التكافؤ أيضاً Ti2O3 ذو اللون البنفسجي. وتجدر الإشارة إلى وجود عدد قليل من مركبات التيتانيوم الثنائي التكافؤ إلا أن الشاردة Ti+2 لا توجد حرة في المحلول نظراً لسرعة تأكسدها بالماء وتحولها إلى Ti+4. أما مركبات التيتانيوم التي يكون فيها التيتانيوم رباعي التكافؤ فأهمها ثنائي أكسيد التيتانيوم TiO2 الذي يتشكل من أكسدة معدن التيتانيوم بشروط خاصة وبوجود أكسجين الهواء.

أما الطريقة الصناعية لتحضير ثنائي أكسيد التيتانيوم فمبنية على تأثير حمض الكبريت في الإلمينيت بدرجة حرارة 150 ْس ـ 200 ْس مما يؤدي لتكون كبريتيات التيتانيوم TiOSO4 التي تتحلمه بدروها فتتحول إلى هيدروكسيد التيتانيوم الذي يُحوَّل بدوره بالحرارة إلى ثنائي أكسيد التيتانيوم.

يعد ثنائي أكسيد التيتانيوم من الأكاسيد المذبذبة وإن كانت صفته الحمضية هي الغالبة نسبياً؛ وهو مسحوق أبيض ينحل في الأسس القوية مكوناً التيتانات المماثلة للسيليكات؛ وهو ينصهر بدرجة 1600 ْس ويصفرُّ بالتسخين.

يستعمل ثنائي أكسيد التيتانيوم صباغاً أبيض للطلاء (الدهان)، ويباع تجارياً باسم أبيض التيتانيوم، وله قدرة على تغطية السطوح تفوق سبع مرات قدرة أكسيد التوتياء، ويستعمل كذلك لتحضير بعض أنوع الخزف ceramique الكهربائي نظراً لأنه عازل جيد.

ومن مركبات التيتانيوم الرباعي التكافؤ رباعي كلوريد التيتانيوم ويعد في مركبات التيتانيوم المهمة، لأنه يعد الأساس في تحضير معظم مركبات التيتانيوم، وهو سائل يتحلمه بسرعة في الماء (على غرار رباعي كلوريد القصدير):

أما كربيد التيتانيوم فيعد في المركبات الصناعية المهمة إذ إنه مقاوم للحرارة، ويدخل في كثير من الخلائط المستعملة لصنع أدوات القطع السريع للمعادن.

ويشكل التيتانيوم مع الحديد خلائط يطلق عليها اسم فيروتيتانيوم حيث يقوم التيتانيوم بتحسين الصفات الميكانيكية للفولاذ لأنه يمتص الأكسجين والآزوت من الفولاذ فيحول بذلك دون تأكسده من جهة، ويمنع تشكل الفقاعات من جهة أخرى، وبالتالي يحول دون تشكل الفجوات الناجمة عن امتصاص الآزوت.

ويدخل التيتانيوم أيضاً في تركيب كثير من الخلائط المعدنية كخليطة الألمنيوم والقصدير والتيتانيوم المستعملة في صنع بعض المَرْكبات الفضائية. [19]

التصنيع

All welding of titanium must be done in an inert atmosphere of argon or helium to shield it from contamination with atmospheric gases (oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen).[20] Contamination causes a variety of conditions, such as embrittlement, which reduce the integrity of the assembly welds and lead to joint failure.[21]

Titanium is very difficult to solder directly, and hence a solderable metal or alloy such as steel is coated on titanium prior to soldering.[22] Titanium metal can be machined with the same equipment and the same processes as stainless steel.[20]

سبائك التيتانيوم

Common titanium alloys are made by reduction. For example, cuprotitanium (rutile with copper added), ferrocarbon titanium (ilmenite reduced with coke in an electric furnace), and manganotitanium (rutile with manganese or manganese oxides) are reduced.[23]

About fifty grades of titanium alloys are designed and currently used, although only a couple of dozen are readily available commercially.[24] The ASTM International recognizes 31 grades of titanium metal and alloys, of which grades one through four are commercially pure (unalloyed). Those four vary in tensile strength as a function of oxygen content, with grade 1 being the most ductile (lowest tensile strength with an oxygen content of 0.18%), and grade 4 the least ductile (highest tensile strength with an oxygen content of 0.40%).[25] The remaining grades are alloys, each designed for specific properties of ductility, strength, hardness, electrical resistivity, creep resistance, specific corrosion resistance, and combinations thereof.[26]

In addition to the ASTM specifications, titanium alloys are also produced to meet aerospace and military specifications (SAE-AMS, MIL-T), ISO standards, and country-specific specifications, as well as proprietary end-user specifications for aerospace, military, medical, and industrial applications.[27]

التشكيل والسبك

Commercially pure flat product (sheet, plate) can be formed readily, but processing must take into account of the tendency of the metal to springback. This is especially true of certain high-strength alloys.[28][29] Exposure to the oxygen in air at the elevated temperatures used in forging results in formation of a brittle oxygen-rich metallic surface layer called "alpha case" that worsens the fatigue properties, so it must be removed by milling, etching, or electrochemical treatment.[30] The working of titanium is very complicated,[31][32][33] and may include Friction welding,[34] cryo-forging,[35] and Vacuum arc remelting.

الاستخدامات

Titanium is used in steel as an alloying element (ferro-titanium) to reduce grain size and as a deoxidizer, and in stainless steel to reduce carbon content.[36] Titanium is often alloyed with aluminium (to refine grain size), vanadium, copper (to harden), iron, manganese, molybdenum, and other metals.[37] Titanium mill products (sheet, plate, bar, wire, forgings, castings) find application in industrial, aerospace, recreational, and emerging markets. Powdered titanium is used in pyrotechnics as a source of bright-burning particles.[38]

الأصباغ والإضافات والطلاءات

About 95% of all titanium ore is destined for refinement into titanium dioxide (TiO 2), an intensely white permanent pigment used in paints, paper, toothpaste, and plastics.[18] It is also used in cement, in gemstones, and as an optical opacifier in paper.[39]

TiO 2 pigment is chemically inert, resists fading in sunlight, and is very opaque: it imparts a pure and brilliant white color to the brown or grey chemicals that form the majority of household plastics.[2] In nature, this compound is found in the minerals anatase, brookite, and rutile.[36] Paint made with titanium dioxide does well in severe temperatures and marine environments.[2] Pure titanium dioxide has a very high index of refraction and an optical dispersion higher than diamond.[11] Titanium dioxide is used in sunscreens because it reflects and absorbs UV light.[40]

الجوفضاء والبحر

Because titanium alloys have high tensile strength to density ratio,[41] high corrosion resistance,[11] fatigue resistance, high crack resistance,[42] and ability to withstand moderately high temperatures without creeping, they are used in aircraft, armor plating, naval ships, spacecraft, and missiles.[11][2] For these applications, titanium is alloyed with aluminium, zirconium, nickel,[43] vanadium, and other elements to manufacture a variety of components including critical structural parts, landing gear, firewalls, exhaust ducts (helicopters), and hydraulic systems. In fact, about two thirds of all titanium metal produced is used in aircraft engines and frames.[44] The titanium 6AL-4V alloy accounts for almost 50% of all alloys used in aircraft applications.[45]

The Lockheed A-12 and the SR-71 "Blackbird" were two of the first aircraft frames where titanium was used, paving the way for much wider use in modern military and commercial aircraft. A large amount of titanium mill products are used in the production of many aircraft, such as (following values are amount of raw mill products used, only a fraction of this ends up in the finished aircraft): 116 metric tons are used in the Boeing 787, 77 in the Airbus A380, 59 in the Boeing 777, 45 in the Boeing 747, 32 in the Airbus A340, 18 in the Boeing 737, 18 in the Airbus A330, and 12 in the Airbus A320.[46] In aero engine applications, titanium is used for rotors, compressor blades, hydraulic system components, and nacelles.[47][48] An early use in jet engines was for the Orenda Iroquois in the 1950s.قالب:Bcn[49]

Because titanium is resistant to corrosion by sea water, it is used to make propeller shafts, rigging, heat exchangers in desalination plants,[11] heater-chillers for salt water aquariums, fishing line and leader, and divers' knives. Titanium is used in the housings and components of ocean-deployed surveillance and monitoring devices for science and military. The former Soviet Union developed techniques for making submarines with hulls of titanium alloys,[50] forging titanium in huge vacuum tubes.[43]

الصناعية

Welded titanium pipe and process equipment (heat exchangers, tanks, process vessels, valves) are used in the chemical and petrochemical industries primarily for corrosion resistance. Specific alloys are used in oil and gas downhole applications and nickel hydrometallurgy for their high strength (e. g.: titanium beta C alloy), corrosion resistance, or both. The pulp and paper industry uses titanium in process equipment exposed to corrosive media, such as sodium hypochlorite or wet chlorine gas (in the bleachery).[51] Other applications include ultrasonic welding, wave soldering,[52] and sputtering targets.[53]

Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4), a colorless liquid, is important as an intermediate in the process of making TiO2 and is also used to produce the Ziegler–Natta catalyst. Titanium tetrachloride is also used to iridize glass and, because it fumes strongly in moist air, it is used to make smoke screens.[40]

المستهلك والمعمار

Titanium metal is used in automotive applications, particularly in automobile and motorcycle racing where low weight and high strength and rigidity are critical.[54] The metal is generally too expensive for the general consumer market, though some late model Corvettes have been manufactured with titanium exhausts,[55] and a Corvette Z06's LT4 supercharged engine uses lightweight, solid titanium intake valves for greater strength and resistance to heat.[56]

Titanium is used in many sporting goods: tennis rackets, golf clubs, lacrosse stick shafts; cricket, hockey, lacrosse, and football helmet grills, and bicycle frames and components. Although not a mainstream material for bicycle production, titanium bikes have been used by racing teams and adventure cyclists.[57]

Titanium alloys are used in spectacle frames that are rather expensive but highly durable, long lasting, light weight, and cause no skin allergies. Titanium is a common material for backpacking cookware and eating utensils. Though more expensive than traditional steel or aluminium alternatives, titanium products can be significantly lighter without compromising strength. Titanium horseshoes are preferred to steel by farriers because they are lighter and more durable.[58]

Titanium has occasionally been used in architecture. The 42.5 m (139 ft) Monument to Yuri Gagarin, the first man to travel in space (55°42′29.7″N 37°34′57.2″E / 55.708250°N 37.582556°E), as well as the 110 m (360 ft) Monument to the Conquerors of Space on top of the Cosmonaut Museum in Moscow are made of titanium for the metal's attractive color and association with rocketry.[59][60] The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Cerritos Millennium Library were the first buildings in Europe and North America, respectively, to be sheathed in titanium panels.[44] Titanium sheathing was used in the Frederic C. Hamilton Building in Denver, Colorado.[61]

Because of titanium's superior strength and light weight relative to other metals (steel, stainless steel, and aluminium), and because of recent advances in metalworking techniques, its use has become more widespread in the manufacture of firearms. Primary uses include pistol frames and revolver cylinders. For the same reasons, it is used in the body of some laptop computers (for example, in Apple's PowerBook G4).[62][63]

In 2023, Apple launched the iPhone 15 Pro, which uses a titanium enclosure.[64]

Some upmarket lightweight and corrosion-resistant tools, such as shovels, knife handles and flashlights, are made of titanium or titanium alloys.[63]

Jewelry

Because of its durability, titanium has become more popular for designer jewelry (particularly, titanium rings).[58] Its inertness makes it a good choice for those with allergies or those who will be wearing the jewelry in environments such as swimming pools. Titanium is also alloyed with gold to produce an alloy that can be marketed as 24-karat gold because the 1% of alloyed Ti is insufficient to require a lesser mark. The resulting alloy is roughly the hardness of 14-karat gold and is more durable than pure 24-karat gold.[65]

Titanium's durability, light weight, and dent and corrosion resistance make it useful for watch cases.[58] Some artists work with titanium to produce sculptures, decorative objects and furniture.[66]

Titanium may be anodized to vary the thickness of the surface oxide layer, causing optical interference fringes and a variety of bright colors.[67] With this coloration and chemical inertness, titanium is a popular metal for body piercing.[68]

Titanium has a minor use in dedicated non-circulating coins and medals. In 1999, Gibraltar released the world's first titanium coin for the millennium celebration.[69] The Gold Coast Titans, an Australian rugby league team, award a medal of pure titanium to their player of the year.[70]

الطبية

Because titanium is biocompatible (non-toxic and not rejected by the body), it has many medical uses, including surgical implements and implants, such as hip balls and sockets (joint replacement) and dental implants that can stay in place for up to 20 years.[1] The titanium is often alloyed with about 4% aluminium or 6% Al and 4% vanadium.[71]

Titanium has the inherent ability to osseointegrate, enabling use in dental implants that can last for over 30 years. This property is also useful for orthopedic implant applications.[1] These benefit from titanium's lower modulus of elasticity (Young's modulus) to more closely match that of the bone that such devices are intended to repair. As a result, skeletal loads are more evenly shared between bone and implant, leading to a lower incidence of bone degradation due to stress shielding and periprosthetic bone fractures, which occur at the boundaries of orthopedic implants. However, titanium alloys' stiffness is still more than twice that of bone, so adjacent bone bears a greatly reduced load and may deteriorate.[72][73]

Because titanium is non-ferromagnetic, patients with titanium implants can be safely examined with magnetic resonance imaging (convenient for long-term implants). Preparing titanium for implantation in the body involves subjecting it to a high-temperature plasma arc which removes the surface atoms, exposing fresh titanium that is instantly oxidized.[1]

Modern advancements in additive manufacturing techniques have increased potential for titanium use in orthopedic implant applications.[74] Complex implant scaffold designs can be 3D-printed using titanium alloys, which allows for more patient-specific applications and increased implant osseointegration.[75]

Titanium is used for the surgical instruments used in image-guided surgery, as well as wheelchairs, crutches, and any other products where high strength and low weight are desirable.[76]

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles are widely used in electronics and the delivery of pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.[77]

تخزين المخلفات النووية

Because of its corrosion resistance, containers made of titanium have been studied for the long-term storage of nuclear waste. Containers lasting more than 100,000 years are thought possible with manufacturing conditions that minimize material defects.[78] A titanium "drip shield" could also be installed over containers of other types to enhance their longevity.[79]

محاذير

Titanium is non-toxic even in large doses and does not play any natural role inside the human body.[8] An estimated quantity of 0.8 milligrams of titanium is ingested by humans each day, but most passes through without being absorbed in the tissues.[8] It does, however, sometimes bio-accumulate in tissues that contain silica. One study indicates a possible connection between titanium and yellow nail syndrome.[80]

As a powder or in the form of metal shavings, titanium metal poses a significant fire hazard and, when heated in air, an explosion hazard.[81] Water and carbon dioxide are ineffective for extinguishing a titanium fire; Class D dry powder agents must be used instead.[2]

When used in the production or handling of chlorine, titanium should not be exposed to dry chlorine gas because it may result in a titanium–chlorine fire.[82]

Titanium can catch fire when a fresh, non-oxidized surface comes in contact with liquid oxygen.[83]

الوظيفة في النبات

An unknown mechanism in plants may use titanium to stimulate the production of carbohydrates and encourage growth. This may explain why most plants contain about 1 part per million (ppm) of titanium, food plants have about 2 ppm, and horsetail and nettle contain up to 80 ppm.[8]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^

"Diesem zufolge will ich den Namen für die gegenwärtige metallische Substanz, gleichergestalt wie bei dem Uranium geschehen, aus der Mythologie, und zwar von den Ursöhnen der Erde, den Titanen, entlehnen, und benenne also diese neue Metallgeschlecht: Titanium; ... "[7]

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Emsley 2001, p. 452

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHistoryAndUse - ^ Barksdale 1968, p. 732

- ^ Gregor, William (1791). "Beobachtungen und Versuche über den Menakanit, einen in Cornwall gefundenen magnetischen Sand" [Observations and experiments regarding menaccanite [i.e., ilmenite], a magnetic sand found in Cornwall]. Chemische Annalen (in الألمانية). 1: pp. 40–54, 103–119.

- ^ Gregor, William (1791). "Sur le menakanite, espèce de sable attirable par l'aimant, trouvé dans la province de Cornouilles" [On menaccanite, a species of magnetic sand, found in the county of Cornwall]. Observations et Mémoires sur la Physique (in الفرنسية). 39: 72–78, 152–160.

- ^ Habashi, Fathi (January 2001). "Historical Introduction to Refractory Metals". Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review. 22 (1): 25–53. Bibcode:2001MPEMR..22...25H. doi:10.1080/08827509808962488. S2CID 100370649.

- ^ Klaproth, Martin Heinrich (1795). "Chemische Untersuchung des sogenannten hungarischen rothen Schörls" [Chemical investigation of the so-called Hungarian red tourmaline [rutile]]. Beiträge zur chemischen Kenntniss der Mineralkörper [Contributions to the chemical knowledge of mineral substances]. Berlin, DE: Heinrich August Rottmann. 1: 233–244.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEmsley2001p451 - ^ Twenty-five years of Titanium news: A concise and timely report on titanium and titanium recycling. Suisman Titanium Corporation. 1995. p. 37. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://books.google.com/books?id=amIQAQAAMAAJ. - ^ أ ب Roza 2008, p. 9

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLANL - ^ أ ب Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, p. 955

- ^ van Arkel, A.E.; de Boer, J.H. (1925). "Preparation of pure titanium, zirconium, hafnium, and thorium metal". Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 148: 345–50. doi:10.1002/zaac.19251480133.

- ^ Yanko, Eugene (2006). "Submarines: General information". Omsk VTTV Arms Exhibition and Military Parade JSC. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "VSMPO stronger than ever" (PDF). Stainless Steel World. KCI Publishing B.V. July–August 2001. pp. 16–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ Jasper, Adam, ed. (2020). Architecture and Anthropology. Taylor & Francis. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-351-10627-6.

- ^ Defense National Stockpile Center (2008). Strategic and Critical Materials Report to the Congress. Operations under the Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act during the Period October 2007 through September 2008. United States Department of Defense. p. 3304. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. https://www.dnsc.dla.mil/Uploads/Materials/esolomon_5-21-2009_13-29-4_2008OpsReport.pdf. - ^ أ ب "Titanium". USGS Minerals Information. United States Geological Survey (USGS).

- ^ عبد المجيد البلخي. "التيتانيوم". الموسوعة العربية.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBarksdale1968p734 - ^ Engel, Abraham L.; Huber, R.W.; Lane, I.R. (1955). Arc-welding Titanium. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines.

- ^ Lewis, W.J.; Faulkner, G.E.; Rieppel, P.J. (1956). Report on Brazing and Soldering of Titanium. Titanium Metallurgical Laboratory, Battelle Memorial Institute.

- ^ "Titanium". Microsoft Encarta. 2005. Archived from the original on 27 October 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- ^ Donachie 1988, p. 16, Appendix J

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEmsley2001p453 - ^ "Volume 02.04: Non-ferrous Metals". Annual Book of ASTM Standards. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International. 2006. section 2. ISBN 978-0-8031-4086-8. "Volume 13.01: Medical Devices; Emergency Medical Services". Annual Book of ASTM Standards. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International. 1998. sections 2 & 13. ISBN 978-0-8031-2452-3.

- ^ Donachie 1988, pp. 13–16, Appendices H and J

- ^ AWS G2.4/G2.4M:2007 Guide for the Fusion Welding of Titanium and Titanium Alloys. Miami: American Welding Society. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 December 2010.

- ^ Titanium design and fabrication handbook for industrial applications. Dallas: Titanium Metals Corporation. 1997. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009.

- ^ Chen, George Z.; Fray, Derek J.; Farthing, Tom W. (2001). "Cathodic deoxygenation of the alpha case on titanium and alloys in molten calcium chloride". Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 32 (6): 1041. doi:10.1007/s11663-001-0093-8. S2CID 95616531.

- ^ "Fabrication of Titanium and Titanium Alloys | Total Materia".

- ^ https://www.titaniuminfogroup.com/forging-process-of-titanium-alloy.html.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ (PDF) https://www.aubertduval.com/wp-media/uploads/2021/06/brochure-titane_2021.pdf.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Linear Friction Welding: A Solution for Titanium Forgings".

- ^ "Ultra-Cold Forging Makes Titanium Strong and Ductile". 21 October 2021.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEBC - ^ Hampel, Clifford A. (1968). The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 738. ISBN 978-0-442-15598-8.

- ^ Mocella, Chris; Conkling, John A. (2019). Chemistry of Pyrotechnics. CRC Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-351-62656-9.

- ^ Smook, Gary A. (2002). Handbook for Pulp & Paper Technologists (3rd ed.). Angus Wilde Publications. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-9694628-5-9.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةStwertka1998 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTICE6th - ^ Moiseyev, Valentin N. (2006). Titanium Alloys: Russian Aircraft and Aerospace Applications. Taylor and Francis, LLC. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-8493-3273-9.

- ^ أ ب Kramer, Andrew E. (5 July 2013). "Titanium Fills Vital Role for Boeing and Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ أ ب Emsley 2001, p. 454

- ^ Donachie 1988, p. 13

- ^ Froes, F.H., ed. (2015). Titanium Physical Metallurgy, Processing, and Applications. ASM International. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-62708-080-4.

- ^ "Titanium in Aerospace – Titanium" (in الإنجليزية). 2024-04-10. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ "Titanium Metal (Ti) / Sponge / Titanium Powder" (PDF). www.lb7.uscourts.gov. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ "Iroquois". Flight Global (archive). 1957. p. 412. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009.

- ^ "Unravelling a Cold War Mystery" (PDF). CIA. 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ Donachie 1988, pp. 11–16

- ^ Kleefisch, E.W., ed. (1981). Industrial Application of Titanium and Zirconium. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International. ISBN 978-0-8031-0745-8.

- ^ Bunshah, Rointan F., ed. (2001). "chapter 8". Handbook of Hard Coatings. Norwich, NY: William Andrew Inc. ISBN 978-0-8155-1438-1.

- ^ Funatani, K. (9–12 October 2000). "Recent trends in surface modification of light metals § Metal matrix composite technologies" in 20th ASM Heat Treating Society Conference. 1 & 2: 138–144, esp. 141, ASM International.

- ^ "Titanium exhausts". National Corvette Museum. 2006. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ^ "Compact powerhouse: Inside Corvette Z06's LT4 engine 650-hp supercharged 6.2L V-8 makes world-class power in more efficient package". media.gm.com (Press release). General Motors. 20 August 2014.

- ^ Davis, Joseph R. (1998). Metals Handbook. ASM International. p. 584. ISBN 978-0-87170-654-6 – via Internet Archive (archive.org).

- ^ أ ب ت Donachie 1988, pp. 11, 255

- ^ Mike Gruntman (2004). Blazing the Trail: The Early History of Spacecraft and Rocketry. Reston, VA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-56347-705-8.

- ^ Lütjering, Gerd; Williams, James Case (12 June 2007). "Appearance Related Applications". Titanium. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-71397-5.

- ^ "Denver Art Museum, Frederic C. Hamilton Building". SPG Media. 2006. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ^ "Apple PowerBook G4 400 (Original – Ti) Specs". everymac.com. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ أ ب Qian, Ma; Niinomi, Mitsuo (2019). Real-World Use of Titanium. Elsevier Science. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-12-815820-3.

- ^ "Apple Announces iPhone 15 Pro Models With Titanium Enclosure". CNET (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-09-19.

- ^ Gafner, G. (1989). "The development of 990 Gold-Titanium: its Production, use and Properties" (PDF). Gold Bulletin. 22 (4): 112–122. doi:10.1007/BF03214709. S2CID 114336550. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2010.

- ^ "Fine Art and Functional Works in Titanium and Other Earth Elements". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Alwitt, Robert S. (2002). "Electrochemistry Encyclopedia". Chemical Engineering Department, Case Western Reserve University, U.S. Archived from the original on 2 July 2008. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- ^ "Body Piercing Safety". doctorgoodskin.com. 1 August 2006.

- ^ "World Firsts". British Pobjoy Mint. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Turgeon, Luke (20 September 2007). "Titanium Titan: Broughton immortalised". The Gold Coast Bulletin. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- ^ "Orthopaedic Metal Alloys". Totaljoints.info. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Titanium foams replace injured bones". Research News. 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Lavine, Marc S. (11 January 2018). Vignieri, Sacha; Smith, Jesse (eds.). "Make no bones about titanium". Science. 359 (6372): 173.6–174. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..173L. doi:10.1126/science.359.6372.173-f.

- ^ Harun, W.S.W.; Manam, N.S.; Kamariah, M.S.I.N.; Sharif, S.; Zulkifly, A.H.; Ahmad, I.; Miura, H. (2018). "A review of powdered additive manufacturing techniques for Ti-6al-4v biomedical applications" (PDF). Powder Technology. 331: 74–97. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2018.03.010.

- ^ Trevisan, Francesco; Calignano, Flaviana; Aversa, Alberta; Marchese, Giulio; Lombardi, Mariangela; Biamino, Sara; Ugues, Daniele; Manfredi, Diego (2017). "Additive manufacturing of titanium alloys in the biomedical field: processes, properties and applications". Journal of Applied Biomaterials & Functional Materials. 16 (2): 57–67. doi:10.5301/jabfm.5000371. PMID 28967051. S2CID 27827821.

- ^ Qian, Ma; Niinomi, Mitsuo (2019). Real-World Use of Titanium. Elsevier Science. pp. 51, 128. ISBN 978-0-12-815820-3.

- ^ Pinsino, Annalisa; Russo, Roberta; Bonaventura, Rosa; Brunelli, Andrea; Marcomini, Antonio; Matranga, Valeria (28 September 2015). "Titanium dioxide nanoparticles stimulate sea urchin immune cell phagocytic activity involving TLR/p38 MAPK-mediated signalling pathway". Scientific Reports. 5: 14492. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514492P. doi:10.1038/srep14492. PMC 4585977. PMID 26412401.

- ^ Shoesmith, D. W.; Noel, J. J.; Hardie, D.; Ikeda, B. M. (2000). "Hydrogen Absorption and the Lifetime Performance of Titanium Nuclear Waste Containers". Corrosion Reviews. 18 (4–5): 331–360. doi:10.1515/CORRREV.2000.18.4-5.331. S2CID 137825823.

- ^ Carter, L.J.; Pigford, T.J. (2005). "Proof of Safety at Yucca Mountain". Science. 310 (5747): 447–448. doi:10.1126/science.1112786. PMID 16239463. S2CID 128447596.

- ^ Berglund, Fredrik; Carlmark, Bjorn (October 2011). "Titanium, Sinusitis, and the Yellow Nail Syndrome". Biological Trace Element Research. 143 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s12011-010-8828-5. PMC 3176400. PMID 20809268.

- ^ Cotell, Catherine Mary; Sprague, J.A.; Smidt, F.A. (1994). ASM Handbook: Surface Engineering (10th ed.). ASM International. p. 836. ISBN 978-0-87170-384-2.

- ^ Compressed Gas Association (1999). Handbook of compressed gases (4th ed.). Springer. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-412-78230-5.

- ^ Solomon, Robert E. (2002). Fire and Life Safety Inspection Manual. National Fire Prevention Association (8th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-87765-472-8.

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 errors: missing title

- CS1 errors: bare URL

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- تيتانيوم

- Aerospace materials

- Biomaterials

- Chemical elements with hexagonal close-packed structure

- Native element minerals

- Pyrotechnic fuels

- عناصر كيميائية

- فلزات انتقالية