الإمبراطورية البرتغالية في الأرخبيل الإندونيسي

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

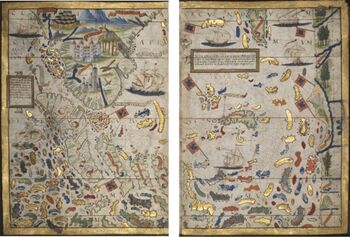

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish a colonial presence in the Indonesian Archipelago. Their quest to dominate the source of the spices that sustained the lucrative spice trade in the early 16th century, along with missionary efforts by Roman Catholic orders, saw the establishment of trading posts and forts, and left behind a Portuguese cultural element that remains in modern-day Indonesia.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التأسيس

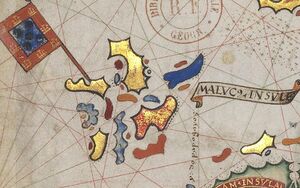

Europeans were making technological advances in the early 16th century; new-found Portuguese expertise in navigation, shipbuilding and weaponry allowed them to make daring expeditions of exploration and expansion. Starting with the first exploratory expeditions sent from newly conquered Malacca in 1512, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in the East Indies, and sought to dominate the sources of valuable spices[1] and to extend their Roman Catholic missionary efforts. Initial Portuguese attempts to establish a coalition and peace treaty in 1522 with the West Javan Sunda Kingdom[2] failed, owing to hostilities among islamic kingdoms on Java. The Portuguese turned east to Moluccas, which comprised a varied collection of principalities and kingdoms that were occasionally at war with each other but maintained significant inter-island and international trade. Through both military conquest and alliance with local rulers, they established trading posts, forts, and missions in the North Sulawesi and in the Spice Islands, including Ternate, Ambon, and Solor.

The height of Portuguese missionary activities, however, came in the latter half of the 16th century, after the pace of their military conquest in the archipelago had stopped and their East Asian interest was shifting to Portuguese India, Portuguese Ceylon, Japan, Macau and China; and sugar in Brazil and the Atlantic slave trade in turn further distracted their efforts in the East Indies. In addition, the first European people to arrive in Northern Sulawesi were the Portuguese. Francisco Xavier supported and visited the Portuguese mission at Tolo on Halmahera. This was the first Catholic mission in the Moluccas. The mission began in 1534 when some chiefs from Morotai came to Ternate asking to be baptised. Simão Vaz, the vicar of Ternate, went to Tolo to found the mission. The mission was the source of conflict between the Spanish, the Portuguese and Ternate. Simão Vaz was later murdered at Sao.[3][4]

الاضمحلال والذكرى

The Portuguese presence in the East Indies was reduced to Solor, Flores and Timor (see Portuguese Timor), alongside a small community in Kampung Tugu[5] following defeat in 1575 at Ternate at the hands of indigenous Ternateans, Dutch conquests in Ambon, north Maluku and Banda, and a general failure for sustained control of trade in the region.[6] In comparison with the original Portuguese ambition to dominate Asian trade, their influences on modern Indonesian culture are minor: the romantic keroncong guitar ballads, a number of Indonesian words and some family names in eastern Indonesia such as da Costa, Dias, de Fretes, and Gonsalves. The most significant impacts of the Portuguese arrival were the disruption and the disorganisation of the trade network, mostly as a result of their conquest of Portuguese Malacca and the first significant plantings of Christianity in Indonesia, with the Kristang people. Christian communities in eastern Indonesia have continued to exist and have contributed to a sense of shared interest with Europeans, particularly among the Ambonese.[7]

انظر أيضاً

- شركة الهند الشرقية البرتغالية

- العلاقات الإندونيسية البرتغالية

- Portuguese loanwords in Indonesian

- Mardijker people

- Portuguese Indonesian

- Timeline of Indonesian history

- List of topics on the Portuguese Empire in the East

- تيمور البرتغالية

المراجع

- ^ Ricklefs, M.C (1969). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300, second edition. London: MacMillan. pp. 22–24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- ^ Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta, Jilid I: Dokumen-dokumen sejarah Jakarta sampai dengan akhir abad ke-16. Cipta Loka Caraka. 1999.;Zahorka, Herwig (2007). The Sunda Kingdoms of West Java, From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with Royal Center of Bogor, Over 1000 Years of Prosperity and Glory. Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka.

- ^ Vaz, Simon. Halmahera dan Raja Ampat sebagai kesatuan majemuk: studi-studi terhadap. p. 279.

- ^ Francis Xavier; His Life, His Times: Indonesia and India, 1545-1549. Xaviers mission. p. 179.

- ^ "A comunidade de Tugu" (in البرتغالية). Instituto Camões. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ^ Miller, George, ed. (1996). To The Spice Islands and Beyond: Travels in Eastern Indonesia. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. xv. ISBN 967-65-3099-9.

- ^ Ricklefs (1991), pp. 22 to 26

- ^ The term Indonesia did not yet exist

- CS1 البرتغالية-language sources (pt)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Former country articles categorised by government type

- Pages with empty portal template

- Portuguese colonialism in Indonesia

- 1522 establishments in the Portuguese Empire