إيتو هيروبومي

إيتو هيروبومي | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

伊藤 博文 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

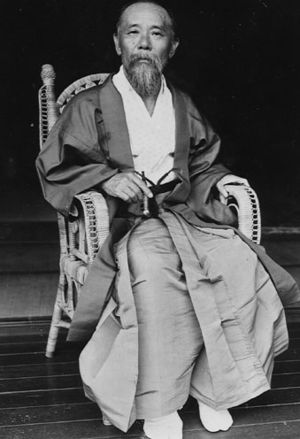

بورتريه لـ"إيتو هيروبومي" | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Privy Council | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 14 June – 26 October 1909 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Yamagata Aritomo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Yamagata Aritomo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 13 July 1903 – 21 December 1905 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Saionji Kinmochi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Yamagata Aritomo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 1 June 1891 – 8 August 1892 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Oki Takato | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Oki Takato | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 30 April 1888 – 30 October 1889 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Oki Takato | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Japan | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 19 October 1900 – 10 May 1901 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Yamagata Aritomo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Saionji Kinmochi (Acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 12 January 1898 – 30 June 1898 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Matsukata Masayoshi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Ōkuma Shigenobu | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 8 August 1892 – 31 August 1896 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Matsukata Masayoshi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Kuroda Kiyotaka (Acting) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 22 December 1885 – 30 April 1888 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| العاهل | Meiji | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | Position established Tokugawa Yoshinobu (as Shōgun) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | Kuroda Kiyotaka | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| تفاصيل شخصية | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| وُلِد | Hayashi Risuke 16 اكتوبر 1841 Tsukari, Suō, Tokugawa shogunate (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture), Japan | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| توفي | 26 أكتوبر 1909 (aged 68) Harbin, Heilongjiang, Qing China | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبب الوفاة | Assassination by gunshot | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| المثوى | Hirobumi Itō Cemetery, Tokyo, Japan | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحزب | Independent (Before 1900) Constitutional Association of Political Friendship (1900–1909) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| الزوج | Itō Umeko (1848–1924) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأنجال | 3 sons, 2 daughters | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأب | Itō Jūzō | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| المدرسة الأم | University College London[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| التوقيع |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||

إيتو هيروبومي (伊藤 博文, 16 October 1841 – 26 October 1909) من رجال السياسة في اليابان، تولى رئاسة الحكومة مرات عدة في فترة مييجي. He was also a leading member of the genrō, a group of senior statesmen that dictated Japanese policy during the Meiji era. He was born as Hayashi Risuke, also known as Hirofumi, Hakubun, and briefly during his youth as Itō Shunsuke. من أهم أعماله الإصلاحات اقتصادية وإنشاء العملة الوطنية (ين).

A London-educated samurai of the Chōshū Domain and a central figure in the Meiji Restoration, Itō Hirobumi chaired the bureau which drafted the Constitution for the newly formed Empire of Japan. Looking to the West for inspiration, Itō rejected the United States Constitution as too liberal and the Spanish Restoration as too despotic. Instead, he drew on British and German models, particularly the Prussian Constitution of 1850. Dissatisfied with Christianity's pervasiveness in European legal precedent, he replaced such religious references with those rooted in the more traditionally Japanese concept of a kokutai or "national polity" which hence became the constitutional justification for imperial authority.

During the 1880s, Itō emerged as the de facto leader of the Meiji oligarchy.[2][3][4] By 1885, he became the first Prime Minister of Japan, a position he went on to hold four times (thereby making his tenure one of the longest in Japanese history). Even out of office as the nation's head of government, he continued to wield vast influence over Japan's policies as a permanent imperial adviser, or genkun, and the President of the Emperor's Privy Council. A staunch monarchist, Itō favored a large, all-powerful bureaucracy that answered solely to the Emperor and opposed the formation of political parties. His third term as prime minister was ended in 1898 by the opposition's consolidation into the Kenseitō party, prompting him to found the Rikken Seiyūkai party to counter its rise. In 1901, he resigned his fourth and final ministry upon tiring of party politics.

On the world stage, Itō presided over an ambitious foreign policy. He strengthened diplomatic ties with the Western powers including Germany, the United States and especially the United Kingdom. In Asia, he oversaw the First Sino-Japanese War and negotiated the surrender of China's ruling Qing dynasty on terms aggressively favourable to Japan, including the annexation of Taiwan and the release of Korea from the Chinese Imperial tribute system. While expanding his country's claims in Asia, Itō sought to avoid conflict with the Russian Empire through the policy of Man-Kan kōkan – the proposed surrender of Manchuria to Russia's sphere of influence in exchange for recognition of Japanese hegemony in Korea. However, in a diplomatic visit to Saint Petersburg in November 1901, Itō found Russian authorities completely unreceptive to such terms. Consequently, Japan's incumbent prime minister, Katsura Tarō, elected to abandon the pursuit of Man-Kan kōkan, which resulted in an escalation of tensions culminating in the Russo-Japanese War.

After Japanese forces emerged victorious over Russia, the ensuing Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 made Itō the first Japanese Resident-General of Korea. He consented to the total annexation of Korea in response to pressure from the increasingly powerful Imperial Army. Shortly thereafter, he resigned as Resident-General in 1909 and assumed office once again as President of the Imperial Privy Council. Four months later, Itō was assassinated by Korean-independence activist and nationalist An Jung-geun in Harbin, Manchuria.[5][6] The annexation process was formalised by another treaty in 1910 which brought Korea under Japanese rule, following year after Itō's death. Through his daughter Ikuko, Itō was the father-in-law of politician, intellectual and author Suematsu Kenchō.

السيرة

المولد

كان ابنا بالتبني لأحد رجال الساموراي من معقل الـ"نشوشو" (غربي البلاد). كان والعديد من رجال الإصلاحات من تلاميذ "يوشيده شو-إين". عام 1863 م تم قبوله ليصبح من رجال الساموراي. قام الزعماء في معقله في "تشوشو" بإرساله مع آخرين إلى إنكلترا لدراسة العلوم الغربية. عاد في نفس السنة ليعايش تدمير القوات الغربية لميناء "شيمونوسيكي" في العام الموالي (1864 م).

الإصلاحات

بدأت الإصلاحات سنة 1868 م، فأصبح "إيتو" محافظا على "هيوجو" (محافظة جديدة استحدث أثناء هذه الفترة). تم إرساله إلى الولايات المتحدة الأميركية لدراسة الأنظمة المالية الغربية. بعد عودته كان له الفضل في إطلاق أول عملة وطنية يابانية، الـ"ين" (عام 1870 م). شد سنة 1871 م مع العديد من كبار المسئولين رحالهم إلى الدول الغربية ("بعثة إيواكورا")، استمرت البعثة حتى 1873 م. بعد عودته أصبح مستشارا في الحكومة الجديدة، ثم استخلف "أوكوبو توشيميتشي" على رأس وزارة الداخلية عام 1878 م. تم اختياره لتحضير دستور جديد للبلاد، ثم قاد عام 1885 م أول حكومة تعمل رسميا في ظل هذا الدستور. تولى منصب رئيس الحكومة لمرات عدة (1892-1896 م، 1898-1899 م ثم 1900-1901 م) قاد مفاوضات "شيمونوسيكي" (1895 م) والتي وضعت حدا للحرب الصينية-اليابانية، أصبحت اليابان بعده من كبرى القوى في المنطقة.

في أعلى هرم السلطة

سنة 1903 م تم تعينيه مستشارا لدى البلاط الملكي في كوريا، ثم أصبح (1906-1907 م) القائد العام على كوريا، عمل أثناءها على بسط سيطرة الإدارة اليابانية على البلاد. يوم 22 يونيو 1907 م أعلن الإمبراطور الكوري "كوجونغ" (لآخر الأباطرة من سلالة الـ"يي") تخليه عن السلطة، تبع ذلك موجة عارمة الانتفاضات ضد التواجد الياباني في كوريا، قادت مجموعة من قدماء الجنود في الجيش الكوري هذه الحركة وأطلقوا على أنفسهم اسم "جيوش العدالة" ، لاحقا انظم غليهم العديد من الأهالي والفلاحين، شن هؤلاء حرب عصابات ضد الاحتلال الياباني، دامت هذه حتى 1909 م. كانت لـ"إيتو" مواقف متناقضة أثناء هذه الفترة (حتى 1909 م)، فقد كان المحرض الرئيس في دفع حاكم كوريا (الإمبراطور) للاستقالة، إلا أنه عدل من مواقفه لاحقا، فأعلن تأييده لخطة استقلال كوريا، مبررا ذلك بأن ضم اليابان لكوريا ستنجم عنه عواقب وخيمة. حاول إقناع الحكومة اليابانية بالعدول عن قرار الضم، وأمام رفض الأخيرة، قدم استقالته يوم 15 يونيو 1909 م، كان يخشى أن يتم إقحامه في أي من القرارات التي تنوي الحكومة الإمبراطورية اتخاذها لاحقا في شأن كوريا.

الجنرال المقيم في كوريا

On 9 November 1905, following the Russo-Japanese War, Itō arrived in Hanseong and gave a letter from the Emperor of Japan to Gojong, Emperor of Korea, asking him to sign the Japan–Korea Protectorate Treaty, which would make Korea a Japanese protectorate. On 15 November 1905, he ordered Japanese troops to encircle the Korean imperial palace.

On 17 November 1905, Itō and Japanese Field Marshal Hasegawa Yoshimichi entered the Jungmyeongjeon Hall, a Russian-designed building that was once part of Deoksu Palace, to persuade Gojong to approve the treaty, but the Emperor refused. Itō then pressured the Emperor's ministers with the implied, and later stated, threat of bodily harm, to sign the treaty.[7] Five ministers signed an agreement that had been prepared by Itō in the Jungmyeongjeon. The agreement gave Imperial Japan complete responsibility for Korea's foreign affairs,[8] and placed all trade through Korean ports under Imperial Japanese supervision.

After the treaty had been signed, Itō became the first Resident-General of Korea on 21 December 1905. In 1907, he urged Emperor Gojong to abdicate in favor of his son Sunjong and secured the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907, thereby giving Japan authority to dictate Korea's internal affairs.

While Itō was firmly against Korea falling into China or Russia's sphere of influence, he also opposed its annexation, advocating instead that the territory should be treated as a protectorate. When the cabinet voted in favor of annexing Korea, he proposed that the process be delayed in the hopes that the decision could eventually be reversed.[9] However, Itō ultimately changed his mind and approved plans to have the region annexed on 10 April 1909. Despite changing his position, he was forced to resign on 14 June 1909 by the Imperial Japanese Army (one of the foremost advocates for Korea's annexation).[10] His assassination is believed to have accelerated the path to the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty.[11]

النهاية

أرسل "إيتو" في آخر مهمة لتشاور مع الروس، ومعرفة موقفهم في حال ضم اليابان لكوريا. في يوم 26 ديسمبر 1909 م، يقوم أحد ضباط "جيش العدالة" وهو "آن تشونغ غون" باغتياله في محطة "هاربين". اتخذ العسكريون في الحكومة اليابانية من حادث اغتياله ذريعة لقرار ضم كوريا في نفس السنة.

Assassination

Itō arrived at the Harbin railway station on 26 October 1909 for a meeting with Vladimir Kokovtsov, a Russian representative in Manchuria. There An Jung-geun, a Korean nationalist[11] and independence activist,[12][13] fired six shots, three of which hit Itō in the chest. He died shortly thereafter. His body was returned to Japan on the Imperial Japanese Navy cruiser Akitsushima, and he was accorded a state funeral on 4 November 1909 at Hibiya Park.[14] An Jung-geun later listed "15 reasons why Itō should be killed" at his trial.[15][16] On 14 February 1910, Ahn was sentenced to death by hanging, Yu to two years in prison, and Cao and Liu to one year and six months in prison for murder and crimes against the Imperial Japanese Government.

الذكرى

في اليابان

- A portrait of Itō Hirobumi was on the obverse of the Series C 1,000 yen note from 1963 until a new series was issued in 1984.

- The publishing company Hakubunkan takes its name from Hakubun, an alternate pronunciation of Itō's given name.

Itō Hirobumi former residence in Hagi

The house where Itō lived from age 14 in Hagi after his father was adopted by Itō Naoemon still exists, and is preserved as a museum. It is a one-story house with a thatched roof and a gabled roof, with a total floor area of 29 tsubo and is located 150 meters south of the Shōkasonjuku Academy. The adjacent villa is a portion of a house built by Itō in 1907 in Oimura, Shimoebara-gun, Tokyo (currently Shinagawa, Tokyo). It was a large Western-style mansion, of which three structures, a part of the entrance, a large hall, and a detached room, were transported Hagi. The large hall has a mirrored ceiling and its wooden paneling uses 1000-year old cedar trees from Yoshino.[17] The buildings were collectively designated a National Historic Site in 1932.[18]

In Korea

The Annals of Sunjong record that Gojong held a positive view of Itō's governorship. In an entry for 28 October 1909, almost three years after being forced to abdicate his throne, the former emperor praised Itō, who had died two days earlier, for his efforts to develop Japanese civilization in Korea. However, the integrity of Joseon silloks dated after the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1905 is considered dubious by Korean scholars due to the influence exerted over record-keeping by the Japanese.

Itō has been portrayed several times in Korean cinema. His assassination was the subject of North Korea's An Jung-gun Shoots Itō Hirobumi in 1979 and South Korea's Thomas Ahn Joong Keun in 2004; both films made his assassin An Jung-geun the protagonist. The 1973 South Korean film Femme Fatale: Bae Jeong-ja is a biopic of Itō's alleged adopted Korean daughter Bae Jeong-ja (1870–1952).

Itō argued the Pan-Asian view that if East Asians did not co-operate closely with one another, Japan, Korea and China would all fall victim to Western imperialism. Initially, Gojong and the Joseon government shared that belief and agreed to collaborate with the Japanese military.[19] Korean intellectuals had predicted that the victor of the Russo-Japanese War would assume hegemony over their peninsula, and as an Asian power, Japan enjoyed greater public support in Korea than Russia. However, policies such as land confiscation and the drafting of forced labor turned Korean popular opinion against the Japanese, a trend exacerbated by the arrest or execution of those who resisted.[19] An Jung-geun was also a proponent of what was later called Pan-Asianism. He believed in a union of the three East Asian nations to repel Western imperialism and restore peace in the region.

Itō memorial temple built

On 26 October 1932, the Japanese unveiled in Seoul the Hakubun-ji 博文寺 Buddhist Temple dedicated to Prince Itō. Full official name "Prince Itō Memorial Temple (伊藤公爵祈念寺院)". Situated in then Susumu Tadashidan Park on the north slope of Namsan, which after liberation became Jangchungdan Park 장충단 공원. From October 1945, the main hall served as student home, ca. 1960 replaced by a guest house of the Park Chung-Hee administration, then reconstructed and again a student guest house. In 1979 it was incorporated into the grounds of the Shilla Hotel then opened. Several other parts of the temple are still at the site.

Genealogy

- Hayashi family

∴Hayashi Awajinokami Michioki ┃ ┣━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ ┃ ┃Hayasi Magoemon ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃ Michimoto Michiyo Michisige Michiyoshi Michisada Michikata Michinaga Michisue ┃ ┃ ┃Hayasi Magosaburō Nobukatsu ┃ ┃ ┃Hayasi Magoemon Nobuyoshi ┃ ┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┓ ┃Hayasi Magoemon ┃ ┃ ┃ Nobuaki Sakuzaemon Sojyurō Matazaemon ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃Hayasi Hanroku ┃ Nobuhisa Genzō ┃ ┃ ┣━━━━━━━━━┓ ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃ Sōzaemon Heijihyōe Yoichiemon ┃ ┃ ┏━━━━━━━━━┻━━━━━━┓ ┏━━━━━┫ ┃Hayasi Hanroku ┃ ┃ ┃ Rihachirō Riemon Masuzō Sukezaemon ┃adopted son of Hayasi Rihachirō ┏━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┫ ┃Itō ┃Hayasi Shinbei's wife ┃Morita Naoyoshi's wife Jyuzō woman woman ┃ ┃ ┃'''Itō Hirobumi''' ┃ ┏━━━━━━━╋━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━┓ ┃Itō ┃Kida ┃Itō ┃ ┃ Hirokuni Humiyoshi Shinichi woman woman ┃ ┣━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━┳━━━┓ ┃Itō ┃Shimizu ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃Itō ┃ ┃ ┃ Hirotada Hiroharu Hiromichi Hiroya Hirotada Hiroomi Hironori Hirotsune Hirotaka Hirohide woman woman woman ┃ ┣━━━━━━━┳━━━━━┳━━━━┳━━━━━┳━━━┓ ┃Itō ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃ ┃ Hiromasa woman woman woman woman woman ┃ ┣━━━━━━━┓ ┃Itō ┃ Tomoaki woman

- Itō family

∴ Itō Yaemon ┃ Itō Naoemon (Mizui Buhei)Yaemon's adopted son ┃ Itō Jyuzō (Hayashi Jyuzo)Naoemon's adopted son ┃ Itō Hirobumi (Hayashi Risuke)

التكريم

From the Japanese Wikipedia article

Japanese

Peerages

- Count (7 July 1884)

- Marquess (5 August 1895)

- Prince (21 September 1907)

Decorations

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2 November 1877)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2 November 1877) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (11 February 1889)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (11 February 1889) Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (5 August 1895)

Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (5 August 1895) Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1 April 1906)

Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1 April 1906)

Court ranks

- Fifth rank, junior grade (1868)

- Fifth rank (1869)

- Fourth rank (1870)

- Senior fourth rank (18 February 1874)

- Third rank (27 December 1884)

- Second rank (19 October 1886)

- Senior second rank (20 December 1895)

- Junior First Rank (26 October 1909; posthumous)

Foreign

الإمبراطورية الألمانية:

الإمبراطورية الألمانية:

- Knight 1st Class of the Order of the Crown (1886)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle (22 December 1886); in Brilliants (December 1901)[20][21]

زاكسه-ڤايمار-آيزناخ: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon (29 September 1882)

زاكسه-ڤايمار-آيزناخ: Grand Cross of the Order of the White Falcon (29 September 1882)

الإمبراطورية الروسية:

الإمبراطورية الروسية:

- Knight of the Order of the White Eagle (17 September 1883)

- Knight of the Order of St. Alexander Nevsky (19 March 1896); in Brilliants (28 November 1901)[22][21]

Sweden-Norway: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa (25 May 1885)[21]

Sweden-Norway: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa (25 May 1885)[21] النمسا-المجر: Knight 1st Class of the Order of the Iron Crown (27 September 1885)[21]

النمسا-المجر: Knight 1st Class of the Order of the Iron Crown (27 September 1885)[21] Siam: Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Siam (24 January 1888)[23]

Siam: Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Siam (24 January 1888)[23] إسپانيا الاسترداد: Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (26 October 1896)[21]

إسپانيا الاسترداد: Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (26 October 1896)[21] بلجيكا: Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold (4 October 1897)[21]

بلجيكا: Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold (4 October 1897)[21] الجمهورية الفرنسية الثالثة: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (29 April 1898)[21]

الجمهورية الفرنسية الثالثة: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (29 April 1898)[21] أسرة تشينگ: Order of the Double Dragon, Class I Grade III (5 December 1898)[23]

أسرة تشينگ: Order of the Double Dragon, Class I Grade III (5 December 1898)[23] المملكة المتحدة: Honorary Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (civil division) (14 January 1902)[24][21]

المملكة المتحدة: Honorary Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (civil division) (14 January 1902)[24][21] مملكة إيطاليا: Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation (16 January 1902)[25][21]

مملكة إيطاليا: Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation (16 January 1902)[25][21] الامبراطورية الكورية: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Ruler (18 April 1904)[23]

الامبراطورية الكورية: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Golden Ruler (18 April 1904)[23]

Popular culture

| Year | Title | Portrayed by |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | The Battle of Port Arthur | Hisaya Morishige |

| 2001–02 | Empress Myeongseong | Yoon Joo-sang |

| 2009–11 | Clouds Above the Slope | Gō Katō |

| 2010 | Ryōmaden | Hiroyuki Onoue |

| 2014 | Rurouni Kenshin: The Legend Ends | Yukiyoshi Ozawa |

| 2015 | Burning Flower | Hitori Gekidan |

| 2018 | Segodon | Kenta Hamano |

| 2018 | Mr. Sunshine | Kim In-woo |

| 2022 | Hero | Kim Seung-rak |

See also

References

- ^ "Famous Alumni". UCL. 11 January 2018.

- ^ Craig, Albert M. (14 July 2014) [1st pub. 1986]. "Chapter 2: The Central Government". In Jansen, Marius B.; Rozman, Gilbert (eds.). Japan in Transition: From Tokugawa to Meiji. Princeton University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0691604848.

By 1878 Ōkubo, Kido, and Saigō, the triumvirate of the Restoration, were all dead. There followed a three-year interim during which it was unclear who would take their place. During this time, new problems emerged: intractable inflation, budget controversies, disagreement over foreign borrowing, a scandal in Hokkaido, and increasingly importunate party demands for constitutional government. Each policy issue became entangled in a power struggle of which the principals were Ōkuma and Itō. Ōkuma lost and was expelled from the government along with his followers...¶Itō's victory was the affirmation of Sat-Chō rule against a Saga outsider. Itō never quite became an Ōkubo but he did assume the key role within the collective leadership of Japan during the 1880s.

- ^ Beasley, W.G. (1988). "Chapter 10: Meiji Political Institutions". In Jansen, Marius B. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. V:The Nineteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 657. ISBN 0-521-22356-3.

Now that Ōkubo was dead and Iwakura was getting old, the contest for overall leadership seemed to lie between Itō and Ōkuma, which gave the latter's views a particular importance. He did not submit them until March 1881. They then proved to be a great deal more radical than any of his colleagues had expected, not least in recommending that a parliament be established almost immediately, so that elections could be held in 1882 and the first session convoked in 1883...Ōkuma envisaged a constitution on the British model, in which power would depend on rivalry among political parties and the highest office would go to the man who commanded a parliamentary majority...Implicit in this was a challenge to the Satsuma and Chōshū domination of the Meiji government. Itō at once took it up, threatening to resign if anything like Ōkuma's proposals were accepted. This enabled him to isolate Ōkuma and force him out of the council later in the year.

- ^ Perez, Louis G. (8 January 2013). "Itō Hirobumi". In Perez, Louis G. (ed.). Japan at War:An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 149. ISBN 9781598847420. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

In 1878, Itō became Minister of Home Affairs. He and Ōkuma subsequently became embroiled over the adoption of a constitutional form of government. Itō had Ōkuma ousted from office and assumed primary leadership in the Meiji government...

- ^ "Ahn Jung-geun Regarded as Hero in China". The Korea Times. 10 August 2009. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Dudden, Alexis (2005). Japan's Colonization of Korea: Discourse and Power. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2829-1.

- ^ McKenzie, F.A. (1920). Korea's Fight for Freedom. Fleming H. Revell Company.

- ^ United States. Dept. of State. (1919). Catalogue of treaties: 1814–1918, p. 273, في كتب گوگل

- ^ Umino, Fukuju (2004). Hirobumi Itō and Korean Annexation (Itō hirobumi to kankoku heigou) (in اليابانية). Aoki Shoten. ISBN 978-4-250-20414-2.

- ^ Ogawara, Hiroyuki (2010). 伊藤博文の韓国併合構想と朝鮮社会 (in اليابانية). 岩波書店. ISBN 978-4000221795.

- ^ أ ب Keene, Donald (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912. Columbia University Press. pp. 662–667. ISBN 0-231-12340-X.

- ^ "What Defines a Hero?". Japan Society. Archived from the original on 4 October 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- ^ "안중근". terms.naver.com.

- ^ Nakamura, Kaju (2010) [1910]. Prince Ito – The Man and Statesman – A Brief History of His Life. Lulu Press (reprint). ISBN 978-1445571423.

- ^ "The Harbin Tragedy". The Straits Times. 2 December 1909. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Why Did Ahn Jung-geun Kill Hirobumi Ito?". The Korea Times. 24 August 2009.

- ^ Isomura, Yukio; Sakai, Hideya (2012). (国指定史跡事典) National Historic Site Encyclopedia. 学生社. ISBN 978-4311750403.(in يابانية)

- ^ "伊藤博文旧宅" (in اليابانية). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ أ ب Lee Jeong-sik (이정식) (May 2001). 긴급대특집, 일본 역사교과서 왜곡파문 [Special report on Japan's history textbook issue.]. New DongA (in الكورية). Retrieved 1 May 2012.

... initially many Koreans supported Japanese against Russians, and helped Japanese military. ... Many intellectuals had predicted that whoever wins the Russo-Japanese War, Joseon would be controlled by a victor. Still, they had hoped for the Asian power's victory. .... On 14 April 1904, Japan demanded unrestricted fishing rights all across Korean peninsular. On 28 June, Japan asked for the right to use every unclaimed land in Korea. Many Japanese gangsters had beaten Korean citizens in numerous occasions. ... —1904, U.S. diplomatic cable by Horace Allen, then U.S. representative in Korea. [...러·일전쟁 때 많은 조선인이 일본측에 동조했고, 일본군을 도왔다... 많은 지식인이 전쟁이 끝난 후에 조선은 승자에게 굴(屈)하고 주권을 상실할 것이라 예측했음에도, 러시아보다는 '동족(同族)'인 일본이 승리하기를 바랐다. ... (1) 1904년 4월14일. 일본은 조선반도 전역에서 거의 무제한적인 어업권을 요구했다. (2) 6월28일. 그들은 지금 조선 내 모든 황무지를 점거하고 사용할 수 있는 권리를 요구했다. (3) 많은 수의 일본인 불량배 노동자들이 조선 사람들을 괴롭히고 있다. ...1904 년 주한미국공사 호레스 앨런의 보고서]

- ^ قالب:Cite newspaper The Times

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Clark, Samuel (2016). "Status Consequences of State Honours". Distributing Status: The Evolution of State Honours in Western Europe. Canada: McGill-Queens University Press. p. 322. doi:10.1515/9780773598560. ISBN 9780773598577. JSTOR j.ctt1c99bzh. OCLC 947837811. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ قالب:Cite newspaper The Times

- ^ أ ب ت JAPAN, 独立行政法人国立公文書館 | NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF. "枢密院文書・枢密院高等官転免履歴書 明治ノ二". 国立公文書館 デジタルアーカイブ.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "No. 27397". The London Gazette. 14 January 1902. p. 295.

- ^ قالب:Cite newspaper The Times

Sources

- Nish, Ian (1998). The Iwakura Mission to America and Europe: A New Assessment. Richmond, Surrey: Japan Library. ISBN 9781873410844. OCLC 40410662.

Further reading

- Edward, I. "Japan's Decision to Annex Taiwan: A Study of Itō-Mutsu Diplomacy, 1894–95". Journal of Asian Studies 37#1 (1977): 61–72.

- Hamada Kengi (1936). Prince Ito. Tokyo: Sanseido Co.

- Johnston, John T.M. (1917). World Patriots. New York: World Patriots Co.

- Kusunoki Sei'ichirō (1991). Nihon shi omoshiro suiri: Nazo no satsujin jiken wo oe. Tokyo: Futami bunko.

- Ladd, George T. (1908). In Korea with Marquis Ito

- Nakamura Kaju (1910). [https://archive.org/details/princeitomanand00nakagoog Prince Ito: The Man and the Statesman: A Brief History of His Life. New York: Japanese-American commercial weekly and Anraku Pub. Co.

- Palmer, Frederick (1901). "Marquis Ito: The Great Man of Japan". Scribner’s Magazine 30(5), 613–621.

External links

- Works by or about إيتو هيروبومي at Internet Archive

- About Japan: A Teacher's Resource Ideas about how to teach about Ito Hirobumi in a K–12 classroom

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)- Newspaper clippings about إيتو هيروبومي in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه Ōkubo Toshimichi |

Lord of Home Affairs 1874 |

تبعه Ōkubo Toshimichi |

| Lord of Home Affairs 1878–1880 |

تبعه Matsukata Masayoshi | |

| منصب حديث | Prime Minister of Japan 1885–1888 |

تبعه Kuroda Kiyotaka |

| سبقه Inoue Kaoru |

Minister for Foreign Affairs (Japan) 1887–1888 |

تبعه Ōkuma Shigenobu |

| منصب حديث | President of the Privy Council 1888–1889 |

تبعه Oki Takato |

| President of the House of Peers 1890–1891 |

تبعه Hachisuka Mochiaki | |

| سبقه Oki Takato |

President of the Privy Council 1891–1892 |

تبعه Oki Takato |

| سبقه Matsukata Masayoshi |

Prime Minister of Japan 1892–1896 |

تبعه Kuroda Kiyotaka بصفته Acting Prime Minister |

| Prime Minister of Japan 1898 |

تبعه Ōkuma Shigenobu | |

| سبقه Yamagata Aritomo |

Prime Minister of Japan 1900–1901 |

تبعه Saionji Kinmochi بصفته Acting Prime Minister |

| سبقه Saionji Kinmochi |

President of the Privy Council 1903–1905 |

تبعه Yamagata Aritomo |

| منصب حديث | Resident General of Korea 1905–1909 |

تبعه Sone Arasuke |

| سبقه Yamagata Aritomo |

President of the Privy Council 1909 |

تبعه Yamagata Aritomo |

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- CS1 اليابانية-language sources (ja)

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- Articles with يابانية-language sources (ja)

- CS1 uses الكورية-language script (ko)

- CS1 الكورية-language sources (ko)

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- 1841 births

- 1909 deaths

- 19th-century prime ministers of Japan

- 20th-century Japanese politicians

- 20th-century prime ministers of Japan

- Alumni of University College London

- An Jung-geun

- Assassinated prime ministers of Japan

- Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa

- Critics of religions

- Deaths by firearm in China

- Deified Japanese men

- Foreign ministers of Japan

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Japanese atheists

- Japanese diplomats

- Japanese expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Japanese imperialism and colonialism

- Japanese people murdered abroad

- Japanese people of the Russo-Japanese War

- Japanese politicians assassinated in the 20th century

- Japanese Residents-General of Korea

- Kazoku

- Keijō Nippō people

- Members of the House of Peers (Japan)

- Members of the Iwakura Mission

- Mōri retainers

- Nobles of the Meiji Restoration

- People from Chōshū Domain

- People from Hikari, Yamaguchi

- People murdered in China

- People of the First Sino-Japanese War

- Politicians assassinated in the 1900s

- Politicians from Yamaguchi Prefecture

- Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers

- Rikken Seiyūkai politicians

- Samurai

- رؤساء الوزارة في اليابان

- مواليد 1841

- وفيات 1909