إعلان استقلال الولايات المتحدة

| إعلان استقلال الولايات المتحدة United States Declaration of Independence | |

|---|---|

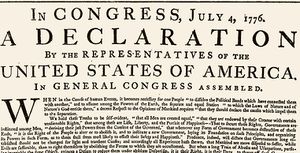

صورة طبق الأصل لعام 1823 من إعلان الاستقلال. | |

| تأسست | يونيو–يوليو 1776 |

| صُدق عليها | 4 يوليو 1776 |

| المكان | Engrossed copy: ادارة الأرشيفات والسجلات الوطنية Rough draft: مكتبة الكونگرس |

| المؤلفون | توماس جفرسون وزملائه |

| الموقعون | 56 ممثل إلى الكونگرس القاري الثاني |

| الغرض | لإعلان وتبرير الانفصال عن بريطانيا العظمى[1] |

إعلان استقلال الولايات المتحدة هو البيان الذي تبناه الكونگرس القاري الثاني في اجتماعه الذي عُقد في مقر ولاية پنسلڤانيا (يُعرف حالياً بقاعة الاستقلال) في فيلادلفيا، پنسلڤانيا، في 4 يوليو 1776. لتعلن أن المستعمرات الأمريكية الثلاثة عشر المتحاربة مع بريطانيا العظمى قد أصبحت ولايات مستقلة، وبالتالي لم تعد جزءاً من الإمبراطورية البريطانية. مكتوب بشكل رئيسي بواسطة توماس جفرسون، يعتبر الإعلان تفسيراً رسمياً لأسباب تصويت الكونگرس في 2 يوليو لصالح إعلان الاستقلال عن بريطانيا العظمى، بعد مرور أكثر من عام على اندلاع حرب الاستقلال الأمريكية. عيد ميلاد الولايات المتحدة -يوم الاستقلال- يحتفل به في 4 يوليو، يوم اعتماد الكونگرس صيغة الإعلان.

بعد إتمام النص في 4 يوليو، أصدر الكونگرس إعلان الاستقلال على أكثر من صورة. فوزع بداية كإعلان مطبوع وزع على نطاق واسع وتليت على مسامع الجمهور. أشهر نسخة من الإعلان، هي النسخة الموقعة التي تعتبر إعلان الاستقلال الرسمي، وهي معروضة في الأرشيف الوطني في واشنطن العاصمة. بالرغم من الموافقة على الإعلان في الرابع من يوليو، إلا أن تاريخ التوقيع عليه هو محل جدل، وقد خلص معظم المؤرخين إلى أن الوثيقة قد وقع عليها تقريبا بعد شهر من تبنيها، في 2 أغسطس 1776، وليس في 4 يوليو كما المعتقد السائد.

كانت نسخ الإعلان وتفسيره موضع الكثير من البحوث العلمية، برر الإعلان الاستقلال عبر سرد العديد من المظالم الاستعمارية ضد الملك جورج الثالث، وعبر التأكيد على بعض الحقوق الطبيعية، ومنها حق الثورة. بعد أن أدت غرضها الأساسي لإعلان الاستقلال، تم مبدئيا تجاهل نص الإعلان بعد الثورة الأمريكية. عظمت مكانتها بمرور الأعوام، خاصة الجملة الثانية، وهي بيان مهم لحقوق الإنسان:

ونحن نرى أن هذه الحقائق بديهية، إن جميع البشر خلقوا متساوين، وأنهم وهبوا من خالقهم حقوق غير قابلة للتصرف، وأن من بين هذه الحقوق حق الحياة والحرية والسعي وراء السعادة.

أطلق على هذه الجملة "واحدة من أشهر الجمل في اللغة الإنگليزية" و"أكثر عبارة قوة وترتيبا في التاريخ الأمريكي"[2]. استخدمت الجملة كثيراً في الدفاع عن حقوق الجماعات المهمشة، وأصبحت تمثل للعديد من الناس المعيار الأخلاقي الذي ينبغي على الولايات المتحدة الدفاع عنه. وقد أثرت وجهة النظر هذه كثيرا في أبراهام لينكون، والذي اتخذ الإعلان كأساس لفلسفته السياسية[3]، وروج لفكرة ان إعلان الاستقلال هو وثيقة للأساسيات التي ينبغي من خلالها تفسير دستور الولايات المتحدة.

خلفية

- «صدقني يا سيدي العزيز، ليس هناك رجل في الإمبراطورية البريطانية يحب الاتحاد الودي مع بريطانيا العظمى مثلما أحبه أنا. لكني، وأقسم بربي الذي خلقني، أفضل الموت على أن أخضع لعلاقة وفق مثل هذه الشروط التي يقرها البرلمان البريطاني، وإنني أؤمن أنني بذلك أمثل وجدان أمريكا». –توماس جفرسون، 29 نوفمبر، 1775.[4]

بحلول الوقت الذي تم تبني إعلان الاستقلال فيه في يوليو 1776، كانت المستعمرات الثلاث عشرة قد دخلت الحرب ضد بريطانيا العظمى لمدة تزيد عن العام. وقد كانت العلاقات بين هذه المستعمرات والبلدة الأم في تدهور منذ 1773. إذ أن البرلمان أقر سلسلة من القوانين لزيادة الإيرادات من المستعمرات، وكان منها قانون الطابع لعام 1765 وقوانين تاونزند لعام 1767. وآمن البرلمان بأن هذه القوانين وسائل شرعية لتدفع من خلالها المستعمرات كلفة بقائها ضمن الإمبراطورية البريطانية.[5] ومع ذلك، كان لدى كثير من المستعمرين رأي آخر بشأن الإمبراطورية. فلأن المستعمرات لم تكن ممثلة بشكل مباشر في البرلمان، نادى المستعمرون بأن البرلمان لا يملك أي حق في فرض ضرائب عليها. وأصبح هذا الخلاف بشأن الضرائب جزءا من خلاف أكبر بين الفهم البريطاني والأمريكي للدستور البريطاني ولحدود سلطة البرلمان على المستعمرات.[6] فوفقا للفهم الأرثذوكسي البريطاني، الذي يرجع تاريخه لثورة 1688 المجيدة، يملك البرلمان سلطة مطلقة على شتى أنحاء الإمبراطورية، ومن ثم، وبالتعريف، فإن كل ما يقوم به البرلمان يعد دستورياً.[7] إلا أن الفكرة التي تنامت في المستعمرات كانت أن الدستور البريطاني ينص على بعض الحقوق الأساسية التي يحظر على أي حكومة انتهاكها، والأمر عينه بالنسبة للبرلمان.[8] بعد صدور قوانين تاونزند، بدأ بعض الكتاب حتى بالتساؤل حول ما إذا كان البرلمان يملك أي سلطة قانونية وقضائية على المستعمرات.[9] وبترقب تنظيم الكومنولث البريطاني بحلول عام 1774، كان الكتاب الأمريكيون مثل صمويل آدامز، جيمس ويلسون، وتوماس جيفرسون ينادون بأن سلطة البرلمان شرعية فقط في بريطانيا، وأن المستعمرات، التي كان لديها هيئات تشريعية خاصة بها، كانت على اتصال ببقية الإمبراطورية عبر ولائها للتاج الملكي فحسب.[10]

انعقاد الكونگرس

اعتبرت مشكلة سلطة البرلمان على المستعمرات كارثية بعد تمرير قوانين قسرية (عرفت في المستعمرات بالقوانين أو القرارات التي لا تطاق) عام 1774 لمعاقبة المستعمرين على قضية جاسبي لعام 1772 وحفل شاي بوسطن عام 1773. رأى الكثير من المستعمرين أن القوانين القسرية كانت انتهاكا للدستور البريطاني وبالتالي كانت انتهاكا لحريات أمريكا البريطانية بأسرها، ولذلك انعقد البرلمان القاري الأول في فيلادلفيا في سبتمبر 1774 لإصدار رد. نظم الكونغرس إثر ذلك مقاطعة للبضائع البريطانية، وقدم عريضة للملك طالب فيها بإلغاء تلك القوانين. فشلت تلك الإجراءات لأن الملك جورج وفريدريك نورث رئيس الوزراء صمما على الإبقاء على فرض السيادة البرلمانية في أمريكا. وقد أرسل الملك إلى نورث في نوفمبر 1774 قائلا: «فلتقرر القذائف ما إذا كانوا سيخضعون لهذا البلد أم سيستقلون».

نحو الاستقلال

تنقيح البنود

ديباجة 15 مايو

قرار لي

الدفعة الأخيرة

المسودة وتبني الإعلان

التأثيرات والوضع القانوني

التوقيع

النشر وردود الفعل

تاريخ الوثائق

الذكرى

التأثير على البلدان الأخرى

احياء الاهتمام

إعلان استقلال جون ترمبول (1817–1826)

العبودية والإعلان

لنكولن والإعلان

حق المرأة في التصويت والإعلان

القرن العشرون وما بعده

الثقافة العامة

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ Becker, Declaration of Independence, 5.

- ^ Ellis, American Creation, 55–56.

- ^ مكفرسون، الثورة الأمريكية الثانية، 126.

- ^ Hazelton, Declaration History, 19.

- ^ Christie and Labaree, Empire or Independence, 31.

- ^ Bailyn, Ideological Origins, 162.

- ^ Bailyn, Ideological Origins, 200–02.

- ^ Bailyn, Ideological Origins, 180–82.

- ^ Middlekauff, Glorious Cause, 241.

- ^ Middlekauff, Glorious Cause, 241–42. The writings in question include Wilson's Considerations on the Authority of Parliament and Jefferson's A Summary View of the Rights of British America (both 1774), as well as Samuel Adams's 1768 Massachusetts Circular Letter.

- ^ Dupont and Onuf, 3.

- ^ Julian P. Boyd, "The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100, number 4 (October 1976), p. 456.

- ^ Wills, Inventing America, 348.

المراجع

- Armitage, David. The Declaration Of Independence: A Global History, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-674-02282-9.

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Enlarged edition. Originally published 1967. Harvard University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-674-44302-0.

- Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. 1922.and Google Book Search. Revised edition New York: Vintage Books, 1970. ISBN 0-394-70060-0.

- Boyd, Julian P. The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text. Originally published 1945. Revised edition edited by Gerard W. Gawalt. University Press of New England, 1999. ISBN 0-8444-0980-4.

- Boyd, Julian P., ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1. Princeton University Press, 1950.

- Boyd, Julian P. "The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100, number 4 (October 1976), 438–67.

- Burnett, Edward Cody. The Continental Congress. New York: Norton, 1941.

- Christie, Ian R. and Benjamin W. Labaree. Empire or Independence, 1760–1776: A British-American Dialogue on the Coming of the American Revolution. New York: Norton, 1976.

- Detweiler, Philip F. "Congressional Debate on Slavery and the Declaration of Independence, 1819–1821", American Historical Review 63 (April 1958): 598–616. in JSTOR

- Detweiler, Philip F. "The Changing Reputation of the Declaration of Independence: The First Fifty Years". William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 19 (1962): 557–74. in JSTOR

- Dumbauld, Edward. The Declaration of Independence And What It Means Today. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950.

- Ellis, Joseph. American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic. New York: Knopf, 2007. ISBN 978-0-307-26369-8.

- Dupont, Christian Y. and Peter S. Onuf, eds. Declaring Independence: The Origins and Influence of America's Founding Document. Revised edition. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Library, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9799997-1-0.

- Ferling, John E. A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-515924-1.

- Friedenwald, Herbert. The Declaration of Independence: An Interpretation and an Analysis. New York: Macmillan, 1904. Accessed via the Internet Archive.

- Gustafson, Milton. "Travels of the Charters of Freedom". Prologue Magazine 34, no 4. (Winter 2002).

- Hamowy, Ronald. "Jefferson and the Scottish Enlightenment: A Critique of Garry Wills's Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence". William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series, 36 (October 1979), 503–23.

- Hazelton, John H. The Declaration of Independence: Its History. Originally published 1906. New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. ISBN 0-306-71987-8. 1906 edition available on Google Book Search

- Journals of the Continental Congress,1774–1789, Vol. 5 ( Library of Congress, 1904–1937)

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution, 1763–1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Mahoney, D. J. (1986). "Declaration of independence". Society. 24: 46–48. doi:10.1007/BF02695936.

- Lucas, Stephen E., "Justifying America: The Declaration of Independence as a Rhetorical Document", in Thomas W. Benson, ed., American Rhetoric: Context and Criticism, Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1989

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Knopf, 1997. ISBN 0-679-45492-6.

- Malone, Dumas. Jefferson the Virginian. Volume 1 of Jefferson and His Time. Boston: Little Brown, 1948.

- Mayer, David (2008). "Declaration of Independence". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 113–15. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n72. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4.

- Mayer, Henry. All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. ISBN 0-312-18740-8.

- McDonald, Robert M. S. "Thomas Jefferson's Changing Reputation as Author of the Declaration of Independence: The First Fifty Years". Journal of the Early Republic 19, no. 2 (Summer 1999): 169–95.

- McPherson, James. Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-19-505542-X.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. Revised and expanded edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Norton, Mary Beth, et al., A People and a Nation, Eighth Edition, Boston, Wadsworth, 2010. ISBN 0-547-17558-2.

- Rakove, Jack N. The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress. New York: Knopf, 1979. ISBN 0-8018-2864-3.

- Ritz, Wilfred J. "The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776". Law and History Review 4, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 179–204.

- Ritz, Wilfred J. "From the Here of Jefferson's Handwritten Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence to the There of the Printed Dunlap Broadside". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 116, no. 4 (October 1992): 499–512.

- Tsesis, Alexander. For Liberty and Equality: The Life and Times of the Declaration of Independence (Oxford University Press; 2012) 397 pages; explores the impact on American politics, law, and society since its drafting.

- Warren, Charles. "Fourth of July Myths". The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, vol. 2, no. 3 (July 1945): 238–72. قالب:Jstor.

- United States Department of State, "The Declaration of Independence, 1776, 1911.

- Wills, Garry. Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1978. ISBN 0-385-08976-7.

- Wills, Garry. Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Rewrote America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 0-671-76956-1.

- Wyatt-Brown, Bertram. Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War Against Slavery. Cleveland: Press of Case Western Reserve University, 1969. ISBN 0-8295-0146-0.

وصلات خارجية

| Find more about إعلان استقلال الولايات المتحدة at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| Media from Commons | |

| Quotations from Wikiquote | |

| Source texts from Wikisource | |

- "Declare the Causes: The Declaration of Independence" lesson plan for grades 9–12 from National Endowment for the Humanities

- Declaration of Independence at the National Archives

- Declaration of Independence at the Library of Congress

- Mobile-friendly Declaration of Independence

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- إعلان استقلال الولايات المتحدة

- الثورة الأمريكية

- تاريخ الولايات المتحدة (1776–89)

- وثائق الولايات المتحدة

- وثائق حكومة الولايات المتحدة

- التنوير الأمريكي

- صكوك حقوق إنسان وطنية

- Documents referencing religion

- أدب الفلسفة السياسية الأمريكية

- يوم الاستقلال (الولايات المتحدة)

- 1776 في القانون

- 1776 في العلاقات الدولية

- 1776 في الولايات المتحدة

- أعمال 1776

- أعمال توماس جفرسون