إسكس

Essex | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Upper: the Hythe, Maldon

Lower: the Dovercourt Lighthouses; and the former Sun Inn, Saffron Walden, displaying pargeting | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الشعار: "Many Minds, One Heart" | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الإحداثيات: 51°45′N 0°35′E / 51.750°N 0.583°E | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| البلد | المملكة المتحدة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المقاطعة | إنگلترة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المنطقة | East | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| التأسيس | Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC±00:00 (توقيت گرينتش المتوسط) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+01:00 (توقيت بريطانيا الصيفي) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| أعضاء البرلمان | List of MPs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الشرطة | Essex Police | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

إسـِكس (بالانجليزية: Essex) مقاطعة إنجليزية تقع في شرق إنجلترا وهي قريبه من مدينة لندن (حوالي 40 كم شرق)، مركز المقاطعة هي بلدة تشلمسفورد ومن البلدات الرئيسية أيضا كولشيستر. حدود المقاطعة الشرقية مطلة على بحر الشمال.

The county has an area of 3,670 km2 (1,420 sq mi) and a population of 1,832,751. After Southend-on-Sea (182,305), the largest settlements are Basildon (115,955), Colchester (130,245) and Chelmsford (110,625).[3] The south of the county is very densely populated, and the remainder, besides Colchester and Chelmsford, is largely rural. For local government purposes Essex comprises a non-metropolitan county, with fourteen districts, and two unitary authority areas: Thurrock and Southend-on-Sea. The districts of Chelmsford, Colchester and Southend have city status. The county historically included north-east Greater London, the River Lea forming its western border.

Essex is a low-lying county with a flat coastline. It contains pockets of ancient woodland, including Epping Forest in the south-west, and in the north-east shares Dedham Vale area of outstanding natural beauty with Suffolk. The coast is one of the longest of any English county, at 562 miles (905km). It is deeply indented by estuaries, the largest being those of the Stour, which forms the Suffolk border, the Colne, Blackwater, Crouch, and the Thames in the south. Parts of the coast are wetland and salt marsh, including a large expanse at Hamford Water, and it contains several large beaches.[4][5]

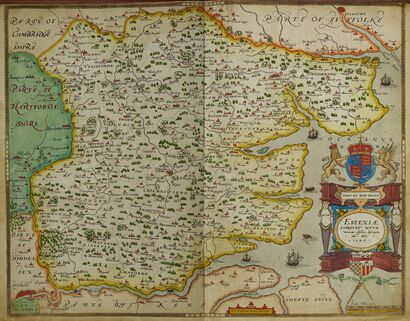

What is now Essex was occupied by the Trinovantes tribe during the Iron Age. They established a settlement at Colchester, which is the oldest recorded town in Britain. The town was conquered by the Romans but subsequently sacked by the Trinovantes during the Boudican revolt. In the Early Middle Ages the region was invaded by the Saxons, who formed the Kingdom of Essex; they were followed by the Vikings, who after winning the Battle of Maldon were able to extract the first Danegeld from King Æthelred. After the Norman Conquest much of the county became a royal forest, and in 1381 the populace of the county were heavily involved in the Peasants' Revolt. The subsequent centuries were more settled, and the county's economy became increasingly tied to that of London; in the nineteenth century the railways allowed coastal resorts such as Clacton-on-Sea to develop and the Port of London to shift downriver to Tilbury. Subsequent development has included the new towns of Basildon and Harlow, the development of the Harwich International Port, and petroleum industry.[4]

History

Essex evolved from the Kingdom of the East Saxons, a polity which is likely to have its roots in the territory of the Iron Age Trinovantes tribe.[6]

Iron Age

Essex corresponds, fairly closely, to the territory of the Trinovantes tribe. Their production of their own coinage marks them out as one of the more advanced tribes on the island, this advantage (in common with other tribes in the south-east) is probably due to the Belgic element within their elite. Their capital was the oppidum (a type of town) of Colchester, Britain's oldest recorded town, which had its own mint. The tribe were in extended conflict with their western neighbours, the Catuvellauni, and steadily lost ground. By AD 10 they had come under the complete control of the Catuvellauni, who took Colchester as their own capital.[7]

Roman

The Roman invasion of AD 43 began with a landing on the south coast, probably in the Richborough area of Kent. After some initial successes against the Britons, they paused to await reinforcements, and the arrival of the Emperor Claudius. The combined army then proceeded to the capital of the Catevellauni-Trinovantes at Colchester, and took it.

Claudius held a review of his invasion force on Lexden Heath where the army formally proclaimed him Imperator. The invasion force that assembled before him included four legions, mounted auxiliaries and an elephant corps – a force of around 30,000 men.[8] At Colchester, the kings of 11 British tribes surrendered to Claudius.[9]

Colchester became a Roman Colonia, with the official name Colonia Claudia Victricensis ('the City of Claudius' Victory'). It was initially the most important city in Roman Britain and in it they established a temple to the God-Emperor Claudius. This was the largest building of its kind in Roman Britain.[10][11]

The establishment of the Colonia is thought to have involved extensive appropriation of land from local people, this and other grievances led to the Trinovantes joining their northern neighbours, the Iceni, in the Boudiccan revolt.[12] The rebels entered the city, and after a Roman last stand at the temple of Claudius, methodically destroyed it, massacring many thousands. A significant Roman force attempting to relieve Colchester was destroyed in pitched battle, known as the Massacre of the Ninth Legion.

The rebels then proceeded to sack London and St Albans, with Tacitus estimating that 70–80,000 people were killed in the destruction of the three cities. Boudicca was defeated in battle, somewhere in the west midlands, and the Romans are likely to have ravaged the lands of the rebel tribes,[13] so Essex will have suffered greatly.

Despite this, the Trinovantes' identity persisted. Roman provinces were divided into civitas for local government purposes – with a civitas for the Trinovantes strongly implied by Ptolemy.[14] Christianity is thought to have been flourishing among the Trinovantes in the fourth century, indications include the remains of a probable church at Colchester,[15] the church dates from sometime after 320, shortly after the Constantine the Great granted freedom of worship to Christians in 313. Other archaeological evidence include a chi-rho symbol etched on a tile at a site in Wickford, and a gold ring inscribed with a chi-rho monogram found at Brentwood. [16]

The late Roman period, and the period shortly after, was the setting for the King Cole legends based around Colchester.[17] One version of the legend concerns St Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great. The legend makes her the daughter of Coel, Duke of the Britons (King Cole) and in it she gives birth to Constantine in Colchester. This, and related legends, are at variance with biographical details as they are now known, but it is likely that Constantine, and his father, Constantius spent time in Colchester during their years in Britain.[18] The presence of St Helena in the country is less certain.

Anglo-Saxon period

The name Essex originates in the Anglo-Saxon period of the Early Middle Ages and has its root in the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) name Ēastseaxe ("East Saxons"), the eastern kingdom of the Saxons who had come from the continent and settled in Britain. Excavations at Mucking have demonstrated the presence of Anglo-Saxon settlers in the early fifth century, however the way in which these settlers became ascendent in the territory of the Trinovantes is not known. Studies suggest a pattern of typically peaceful co-existence, with the structure of the Romano-British landscape being maintained, and with the Saxon settlers believed to have been in the minority.[19]

The first known king of the East Saxons was Sledd in 587, though there are less reliable sources giving an account of Aescwine (other versions call him Erkenwine) founding the kingdom in 527. The early kings of the East Saxons were pagan and uniquely amongst the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms traced their lineage back to Seaxnēat, god of the Saxons, rather than Woden. The kings of Essex are notable for their S-nomenclature, nearly all of them begin with the letter S.

The Kingdom of the East Saxons included not just the subsequent county of Essex, but also Middlesex (including the City of London), much of Hertfordshire and at times also the sub-Kingdom of Surrey. The Middlesex and Hertfordshire parts were known as the Province of the Middle Saxons since at least the early eighth century but it is not known if the province was previously an independent unit that came under East Saxon control. Charter evidence shows that the Kings of Essex appear to have had a greater control in the core area, east of the Lea and Stort, that would subsequently become the county of Essex. In the core area they granted charters freely, but further west they did so while also making reference to their Mercian overlords.

The early kings were pagan, together with much and perhaps by this time all of the population. Sledd's son Sebert converted to Christianity around 604 and St Paul's Cathedral in London was established. On Sebert's death in 616 his sons renounced Christianity and drove out Mellitus, the Bishop of London. The kingdom re-converted after St Cedd, a monk from Lindisfarne and now the patron saint of Essex, converted Sigeberht II the Good around 653.

In AD 824, Ecgberht, the King of the Wessex and grandfather of Alfred the Great, defeated the Mercians at the Battle of Ellandun in Wiltshire, fundamentally changing the balance of power in southern England. The small kingdoms of Essex, Sussex and of Kent, previously independent albeit under Mercian overlordship, were subsequently fully absorbed into Wessex.

The later Anglo-Saxon period shows three major battles fought with the Norse recorded in Essex; the Battle of Benfleet in 894, the Battle of Maldon in 991 and the Battle of Assandun (probably at either Ashingdon or Ashdon) in 1016. The county of Essex was formed from the core area, east of the River Lea,[20] of the former Kingdom of the East Saxons in the 9th or 10th centuries and divided into groupings called Hundreds. Before the Norman conquest the East Saxons were subsumed into the Kingdom of England.

After the Norman Conquest

Having conquered England, William the Conqueror initially based himself at Barking Abbey, an already ancient nunnery, for several months while a secure base, which eventually became the Tower of London could be established in the city. While at Barking William received the submission of some of England's leading nobles. The invaders established a number of castles in the county, to help protect the new elites in a hostile country. There were castles at Colchester, Castle Hedingham, Rayleigh, Pleshey and elsewhere. Hadleigh Castle was developed much later, in the thirteenth century.

After the arrival of the Normans, the Forest of Essex was established as a royal forest, however, at that time, the term[21] was a legal term. There was a weak correlation between the area covered by the Forest of Essex (the large majority of the county) and the much smaller area covered by woodland. An analysis of Domesday returns for Essex has shown that the Forest of Essex was mostly farmland, and that the county as a whole was 20% wooded in 1086.[22]

After that point population growth caused the proportion of woodland to fall steadily until the arrival of the Black Death, in 1348, killed between a third and a half of England's population, leading to a long term stabilisation of the extent of woodland. Similarly, various pressures led to areas being removed from the legal Forest of Essex and it ceased to exist as a legal entity after 1327,[23] and after that time Forest Law applied to smaller areas: the forests of Writtle (near Chelmsford), long lost Kingswood (near Colchester),[22] Hatfield, and Waltham Forest.

Waltham Forest had covered parts of the Hundreds of Waltham, Becontree and Ongar. It also included the physical woodland areas subsequently legally afforested (designated as a legal forest) and known as Epping Forest and Hainault Forest).[24]

Peasants Revolt, 1381

The Black Death significantly reduced England's population, leading to a change in the balance of power between the working population on one hand, and their masters and employers on the other. Over a period of several decades, national government brought in legislation to reverse the situation, but it was only partially successful and led to simmering resentment.

By 1381, England's economic situation was very poor due to the war with France, so a new Poll Tax was levied with commissioners being sent round the country to interrogate local officials in an attempt to ensure tax evasion was reduced and more money extracted. This was hugely unpopular and the Peasants' Revolt broke out in Brentwood on 1 June 1381.

Several thousand Essex rebels gathered at Bocking on 4 June, and then divided. Some heading to Suffolk to raise rebellion there, with the rest heading to London, some directly – via Bow Bridge and others may have gone via Kent. A large force of Kentish rebels also advanced on London while revolt also spread to a number of other parts of the country.

The rebels gained access to the walled City of London and gained control of the Tower of London. They carried out extensive looting in the capital and executed a number of their enemies, but the revolt began to dissipate after the events at West Smithfield on 15 June, when the Mayor of London, William Walworth, killed the rebel leader Wat Tyler. The rebels prepared to fire arrows at the royal party but the 15 year old King Richard II rode toward the crowd and spoke to them, defusing the situation, in part by making a series of promises he did not subsequently keep.[25]

Having bought himself time, Richard was able to receive reinforcements and then crush the rebellion in Essex and elsewhere. His forces defeated rebels in battle at Billericay on 28 June, and there were mass executions; hangings and disembowelling at Chelmsford and Colchester.[26]

Wars of the Roses

In 1471, during the Wars of the Roses a force of around 2,000 Essex supporters of the Lancastrian cause crossed Bow Bridge to join with 3,000 Kentish Lancastrian supporters under the Bastard of Fauconberg.

The Essex men joined with their allies in attempting to storm Aldgate and Bishopsgate during an assault known as the Siege of London. The Lancastrians were defeated, and the Essex contingent retreated back over the Lea with heavy losses.[27]

Armada

In 1588 Tilbury Fort was chosen as the focal point of the English defences against King Philip II's Spanish Armada, and the large veteran army he had ordered to invade England. The English believed that the Spanish would land near the Fort,[28] so Queen Elizabeth's small and relatively poorly trained forces gathered at Tilbury, where the Queen made her famous speech to the troops.

I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

Civil War

Essex, London and the eastern counties backed Parliament in the English Civil War, but by 1648, this loyalty was stretched. In June 1648 a force of 500 Kentish Royalists landed near the Isle of Dogs, linked up with a small Royalist cavalry force from Essex, fought a battle with local parliamentarians at Bow Bridge, then crossed the River Lea into Essex.

The combined force, bolstered by extra forces, marched towards Royalist held Colchester, but a Parliamentarian force caught up with them just as they were about to enter the city's medieval walls, and a bitter battle was fought but the Royalists were able to retire to the security of the walls. The Siege of Colchester followed, but ten weeks' starvation and news of Royalist defeats elsewhere led the Royalists to surrender.[29]

Geography

The ceremonial county of Essex is bounded by Kent, south of the Thames Estuary; Greater London to the south-west; Hertfordshire, broadly west of the River Lea and the Stort; Cambridgeshire to the northwest; Suffolk broadly north of the River Stour; with the North Sea to the east. The highest point of the county of Essex is Chrishall Common near the village of Langley, close to the Hertfordshire border, which reaches 482 feet (147 m).

Boundaries

In England, the term county is currently applied to a number of different geographical units: the historic counties, the ceremonial counties (or lieutenancy areas) and the non-metropolitan counties. Therefore, Essex has different boundaries depending on which type of county is being referred to.

The largest extent of Essex is the historic county, which includes 'Metropolitan Essex' i.e. areas within the London conurbation such as Romford and West Ham.[30][31] This boundary of Essex was established in the late Anglo-Saxon period, sometime after the larger former Kingdom of the East Saxons had lost its independence. It includes the whole ceremonial county, as well as the three north-western parishes (transferred to Cambridgeshire in 1889), and the five London boroughs previously administered as part of Essex.

The administrative county and County Council was formed in 1889.[32] The county was made a non-metropolitan county as part of the 1970s local government reorganisation.[33] Its present boundaries were set in 1998 when the Thurrock and Southend-on-Sea separated from the non-metropolitan county to become unitary authorities.[34] In 1997, the Lieutenancies Act, which defined Essex for ceremonial purposes as the current non-metropolitan county and the unitary authorities formerly part of it.[35]

Until 1996, the Royal Mail additionally divided Britain into postal counties, used for addresses.[36] Although it adopted many local government boundary changes, the Royal Mail did not adopt the 1965 London boundary reform due to cost.[37] Therefore, parts of post-1965 Greater London continued to have an Essex address.[38] The postal county of Hertfordshire also extended deep into west Essex, with Stansted isolated as an exclave of postal Essex. In 1996, postal counties were discontinued and replaced entirely by postcodes, though customers may still use a county, which will be ignored in the sorting process.[38]

Coast

The deep estuaries on the east coast give Essex, by some measures, the longest coast of any county.[39] These estuaries mean the county's North Sea coast is characterised by three major peninsulas, each named after the Hundred based on the peninsula:

- Tendring[40] between the Stour and the Colne.

- Dengie[41] between the Blackwater and the Crouch

- Rochford[42] between the Crouch and the Thames

A consequence of these features is that the broad estuaries defining them have been a factor in preventing any transport infrastructure linking them to neighbouring areas on the other side of the river estuaries, to the north and south.

Settlement patterns

The pattern of settlement in the county is diverse. The areas closest to London are the most densely settled, though the Metropolitan Green Belt has prevented the further sprawl of London into the county. The Green Belt was initially a narrow band of land, but subsequent expansions meant it was able to limit the further expansion of many of the commuter towns close to the capital. The Green Belt zone close to London includes many prosperous commuter towns, as well as the new towns of Basildon and Harlow, originally developed to resettle Londoners after the destruction of London housing in the Second World War; they have since been significantly developed and expanded. Epping Forest also prevents the further spread of the Greater London Urban Area. As it is not far from London, with its economic magnetism, many of Essex's settlements, particularly those near or within short driving distance of railway stations, function as dormitory towns or villages where London workers raise their families. In these areas a high proportion of the population commute to London, and the wages earned in the capital are typically significantly higher than more local jobs. Many parts of Essex therefore, especially those closest to London, have a major economic dependence on London and the transport links that take people to work there.

Part of the south-east of the county, already containing the major population centres of Basildon, Southend and Thurrock, is within the Thames Gateway and designated for further development. Parts of the south-west of the county, such as Buckhurst Hill and Chigwell, are contiguous with Greater London neighbourhoods and therefore form part of the Greater London Urban Area.

A small part of the south-west of the county, Sewardstone, is the only settlement outside Greater London to be covered by a postcode district of the London post town (E4). In rural parts of the county, there are many small towns, villages and hamlets largely built in the traditional materials of timber and brick, with clay tile or thatched roofs.

Administrative history

Before the County Council

Before the creation of the county councils, county-level administration was limited in nature; lord-lieutenants replaced the sheriffs from the time of Henry VIII and took a primarily military role, responsible for the militia and the Volunteer Force that replaced it.

Most administration was carried out by justices of the peace (JPs) appointed by the Lord-Lieutenant of Essex based upon their reputation. The JPs carried out judicial and administrative duties such as maintenance of roads and bridges, supervision of the poor laws, administration of county prisons and setting the County Rate.[43] JPs carried out these responsibilities, mainly through quarter sessions, and did this on a voluntary basis.

At this time the county was sub-divided into units known as Hundreds. At a very early but unknown date, small parts of the county on the east bank of the Stort, near Bishops Stortford and Sawbridgeworth were transferred to Hertfordshire

County Councils

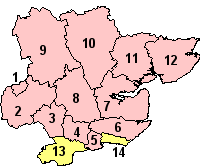

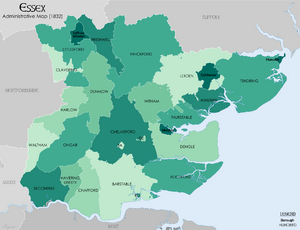

Essex County Council was formed in 1889. However, County Boroughs of West Ham (1889–1965), Southend-on-Sea (1914–1974)[44] and East Ham (1915–1965) formed part of the county but were county boroughs (not under county council control, in a similar manner to unitary authorities today).[45] 12 boroughs and districts provide more localised services such as rubbish and recycling collections, leisure and planning, as shown in the map on the right.

The north-west tip of Essex, the parishes of Great Chishill, Little Chishill and Heydon, were transferred to Cambridgeshire when the County Councils were created in 1889. Parts of a number of other parishes were also transferred at that time, and since.

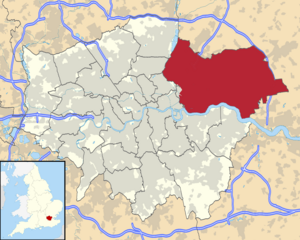

Greater London established

The boundary with Greater London was established in 1965, when East Ham and West Ham county boroughs and the Barking, Chingford, Dagenham, Hornchurch, Ilford, Leyton, Romford, Walthamstow and Wanstead and Woodford districts as well as a part of Chigwell[45] were transferred to form the London boroughs of Barking and Dagenham, Havering, Newham, Redbridge and Waltham Forest.

Two unitary authorities

In 1998, the boroughs of Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock were separated from the administrative county of Essex after successful requests to become unitary authorities.[46][47]

Governance

National

Essex became part of the East of England Government Office Region in 1994 and was statistically counted as part of that region from 1999, having previously been part of the South East England region.

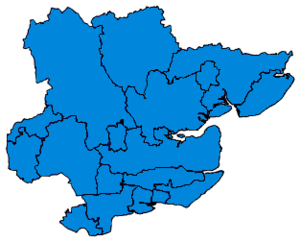

As of the 2019 general election, all 18 Essex seats are represented by Conservatives, all of them with absolute majorities (over 50% of the vote). There have previously been some Labour MPs: most recently, Thurrock, Harlow and Basildon in Labour's 2005 election victory. The Liberal Democrats until 2015 had a sizeable following in Essex, gaining Colchester in the 1997 general election.

The 2015 general election saw a large vote in Essex for the UK Independence Party (UKIP), with its only MP, Douglas Carswell, retaining the seat of Clacton that he had won in a 2014 by-election, and other strong performances, notably in Thurrock and Castle Point, but in the 2017 general election, UKIP's vote share plummeted by 15.6% while both Conservative and Labour rose by 9%. This resulted in Labour regaining second place in Essex, increasing their vote share across the county and cutting some Conservative majorities in areas that had been unaffected by the 1997 general election, namely Rochford and Southend East and Southend West.

In 2015, Thurrock was a three-way marginal, with UKIP, Labour and the Conservatives gaining 30%, 31% and 32% respectively. In 2017, the Conservatives held Thurrock with an increased share of the vote, but a smaller margin of victory. It was the constituency in which UKIP performed best in 2017, with 20% of the vote, while all other areas had been reduced to low single-figure vote shares. Several new MPs were elected in the 2017 election, with Alex Burghart, Vicky Ford, Giles Watling and Kemi Badenoch all replacing senior Conservative politicians Sir Eric Pickles, Sir Simon Burns, Douglas Carswell and Sir Alan Haselhurst, respectively.

At the 2019 general election, Castle Point constituency recorded the highest vote share for the Conservatives in the entire United Kingdom, with 76.7%. The most marginal constituency in the county is Colchester; however the Conservative Party still command a majority of over 9,400 votes.

In the 2016 EU referendum, 62.3% of voters in Essex voted to leave the EU, with all 14 District Council areas voting to leave, the smallest margin being in Uttlesford.[48]

| Party | Votes cast | % | Seats | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ± | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ± | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ± | ||

| Conservative | 436,758 | 528,949 | 577,118 | ▲ 48,169 | 49.6 | 59.0 | 64.8 | ▲ 5.8 | 17 | 18 | 18 | ||

| Labour | 171,026 | 261,671 | 189,471 | 19.4 | 29.2 | 21.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Liberal Democrat | 58,592 | 46,254 | 95,078 | ▲ 48,824 | 6.6 | 5.1 | 10.6 | ▲ 5.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Green | 25,993 | 12,343 | 20,438 | ▲ 8,095 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 2.3 | ▲ 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Independents | 6,919 | 4,179 | 10,224 | ▲ 6,045 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 | ▲ 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Monster Raving Loony | N/A | N/A | 804 | ▲ 804 | N/A | N/A | 0.09 | ▲ 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| English Democrats | 453 | 289 | 532 | ▲ 243 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ▲ 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| SDP | N/A | N/A | 394 | ▲ 394 | N/A | N/A | 0.04 | ▲ 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Psychedelic Future | N/A | N/A | 367 | ▲ 367 | N/A | N/A | 0.04 | ▲ 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| YPP | 80 | 110 | 170 | ▲ 60 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ▲ 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| UKIP | 177,756 | 41,478 | N/A | 20.2 | 4.6 | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Total | 879,918 | 896,231 | 894,608 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 18 | 18 | 18 | ||||

الثقافة

الرموز

three seaxes emblem attributed to him (from John Speed's 1611 Saxon Heptarchy)]] Both the Flag of Essex and the county's coat of arms comprise three Saxon seax knives (although they look rather more like scimitars), mainly white and pointing to the right (from the point of view of the observer), arranged vertically one above another on a red background (Gules three Seaxes fesswise in pale Argent pommels and hilts Or, points to the sinister and notches to the base). The three-seax device is also used as the official logo of Essex County Council; this was granted in 1932.[49]

The emblem was attributed to Anglo-Saxon Essex in Early Modern historiography. The earliest reference to the arms of the East Saxon kings was by Richard Verstegan, the author of A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence (Antwerp, 1605), claiming that "Erkenwyne king of the East-Saxons did beare for his armes, three [seaxes] argent, in a field gules". There is no earlier evidence substantiating Verstegan's claim, which is an anachronism for the Anglo-Saxon period seeing that heraldry only evolved in the 12th century, well after the Norman Conquest.

John Speed in his Historie of Great Britaine (1611) follows Verstegan in his descriptions of the arms of Erkenwyne, but he qualifies the statement by adding "as some or our heralds have emblazed".[49]

The cowslip is the county plant of Essex.[50]

Landmarks and places of interest

Over 14,000 buildings have listed status in the county and around 1,000 of those are recognised as of Grade I or II* importance.[51] The buildings include the 7th century Saxon church of St Peter-on-the-Wall and the clubhouse of the Royal Corinthian Yacht Club which was the United Kingdom's entry in the 'International Exhibition of Modern Architecture' held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1932. Southend Pier is in the Guinness Book of Records as the longest pleasure pier in the world

| المفتاح | |

| كنيسة/كاتدرائية | |

| منطقة مفتوحة للمعاقين | |

| منتزه ترفيهي/حديقة ملاهي | |

| قلعة | |

| منتزه المقاطعة | |

| تراث إنگليزي | |

| هيئة الغابات | |

| سكك حديدية تراثية | |

| بيت تاريخي | |

| متحف (مجاني/غير مجاني) | |

| صندوق وطني | |

| مسرح | |

| حديقة حيوان | |

- Abberton Reservoir

- Anglia Ruskin University Chelmsford campus

- Ashdon (The site of the ancient Bartlow Hills and also a claimant as the location of the Battle of Ashingdon)

- Ashingdon (The site of the Battle of Ashingdon in 1016), near Southend, with its isolated St Andrews Church and site of England's earliest aerodrome at South Fambridge

- Audley End House and Gardens, Saffron Walden

- Brentwood Cathedral

- Clacton-on-Sea

- Chelmsford Cathedral

- Colchester Castle

[52]

[52] - Colchester Zoo

- Colne Valley Railway

- Cressing Temple

- East Anglian Railway Museum

- Epping Forest

- Epping Ongar Railway

- Finchingfield (home of the author Dodie Smith)

- Frinton-on-Sea

- Great Bentley

- Hadleigh Castle

- Harlow New Town

- Hedingham Castle, between Stansted and Colchester, to the north of Braintree

- Ingatestone Hall, Ingatestone, between Brentwood and Chelmsford

- Kelvedon Hatch Secret Nuclear Bunker

- Lakeside Shopping Centre

- Loughton, near Epping Forest

- Maldon historic market town, close to Chelmsford and the North Sea, and site of the Battle of Maldon

- Mangapps Railway Museum

(Burnham-on-Crouch)

(Burnham-on-Crouch) - Marsh Farm Country Park (South Woodham Ferrers)

- Mersea Island, birdwatching and rambling resort with one settlement, West Mersea

- Mistley Towers, Manningtree, between Colchester and Ipswich, near Alton Water.

- Mountfitchet Castle

, Stansted

, Stansted - North Weald Airfield

- Northey Island

- Orsett Hall Hotel, Prince Charles Avenue, Orsett near Chadwell St Mary

- Real Circumstance Theatre Company

- Royal Gunpowder Mills in Waltham Abbey

- St Peter-on-the-Wall

- Saffron Walden

- Southend Pier

- Thames Estuary

- Tilbury Fort

- Thaxted, south of Saffron Walden

- Thurrock Thameside Nature Park

- University of Essex (Wivenhoe Park, Colchester and Loughton)

- Waltham Abbey Church

أشخاص ذوو حيثية

مقاطعات ومناطق شقيقة

انظر أيضاً

- The Earl of Essex

- Q Camp : WWII camp in Essex

- List of civil parishes in England

- Lord Lieutenant of Essex

- High Sheriff of Essex

الهامش

- ^ "Lord-Lieutenant of Essex: Jennifer Tolhurst". GOV.UK (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 13 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "No. 62943". The London Gazette. 13 March 2020. p. 5161.

- ^ "Towns and cities, characteristics of built-up areas, England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ أ ب "Essex | History, Population, & Facts". Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ "Protecting the environment: The Essex coast | Essex County Council". www.essex.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p46. Barbara Yorke. Yorke makes reference to research by Rodwell and Rodwell (1986) and Bassett (1989)

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. passim. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ Described in 'The Essex Landscape', by John Hunter, Essex Record Office, 1999. Chapter 4

- ^ Life in Roman Britain, Anthony Birley, 1964

- ^ Crummy, Philip (1997) City of Victory; the story of Colchester – Britain's first Roman town. Published by Colchester Archaeological Trust (ISBN 1 897719 04 3)

- ^ Wilson, Roger J.A. (2002) A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain (Fourth Edition). Published by Constable. (ISBN 1-84119-318-6)

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 48. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 51. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6.

- ^ Rippon, Stephen (2018) [2018]. Kingdom, Civitas, and County. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-875937-9.

- ^ Details on the church, Colchester Archaeologist website https://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=34126 Archived 11 ديسمبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 58. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6. the reference relates to the flourishing nature of Christiantity in fourth century Essex and the finds at Wickford and Brentwood

- ^ Gray, Adrian (1987) [1987]. Tales of Old Essex. Berkshire: Countryside Books. p. 27. ISBN 0-905392-98-1.

- ^ Dunnett, Rosalind (1975) [1975]. The Trinovantes. London: Duckworth. p. 51. ISBN 0-7156-0843-6. The source states that the earliest record in the 14th century Colchester Oath Book, but recounted by Daniel Defoe and others

- ^ Yorke, Barbara (2005) [1990]. Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and new York: Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

- ^ Vision of Britain Archived 26 يناير 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Essex ancient county boundaries map

- ^ forest

- ^ أ ب Rackham, Oliver (1990) [1976]. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. New York: Phoenix Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-8421-2469-7.

- ^ The Essex Landscape, a study of its form and history. John Hunter, pub Essex Record Office 1999. ISBN 1-898529-15-9

- ^ Raymond Grant (1991). The royal forests of England. Wolfeboro Falls, NH: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-781-X. OL 1878197M. 086299781X. see table, p224 for Essex Stanestreet and p221-229 for details of each forest

- ^ The English: A Social History 1066-1945. p36-37 Christopher Hibbert, Paladin Publishing 1988, ISBN 0 586 08471 1

- ^ Commentary on the Battle of Billericay and the aftermath of the revolt in Essex: Whybra, Julian. "The Battle of Norsey Wood, 1381" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2021.

- ^ Overview of the events of 1471: Rickard, J (27 February 2014). "Siege of London, 12-15 May 1471". Military History Encyclopedia on the Web. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020.

- ^ Connatty, Mary (1987) [1987]. The National Trust Book of the Armada. London: Kingfisher Books. p. 25. ISBN 0-86272-282-9.

- ^ Royle, Trevor (2006). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660. Abacus. pp. 449–452. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- ^ www.abcounties.com (26 June 2013). "Essex". Association of British Counties. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ^ "Metropolitan Essex since 1850: Introduction | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Local Government Act 1888, The National Archives, 1888 c. 41, https://legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1888/41/

- ^ Local Government Act 1974, The National Archives, 1974 c. 40, https://legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/40/

- ^ The Essex (Boroughs of Colchester, Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock and District of Tendring) (Structural, Boundary and Electoral Changes) Order 1996, The National Archives, SI 1996/1875, https://legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1996/1875/made

- ^ Lieutenancies Act 1997 (c. 23).

- ^ "Pembrokeshire (Royal Mail Database) c218WH". Hansard. 23 June 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ "G.P.O. To Keep Old Names. London Changes Too Costly". The Times. 12 April 1966.

- ^ أ ب Geographers' A-Z Map Company (2008). London Postcode and Administrative Boundaries (6 ed.). Geographers' A-Z Map Company. ISBN 978-1-84348-592-6.

- ^ Ordnance Survey Blog on the Essex coastline and the difficulty of measuring coastlines https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/blog/2017/01/english-county-longest-coastline/ Archived 28 يونيو 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ A link to show the term Tendring Peninsula in use and to describe the name as resulting from the name of the Hundred

- ^ link to show the Dengie Peninsula in use and linking that to Hundred organisation

- ^ A link to show the term Rochford Peninsula in use http://www.visitessex.com/rochford.aspx Archived 30 مارس 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ English Social History, Trevelyan

- ^ Vision of Britain Archived 14 أغسطس 2011 at the Wayback Machine – Southend-on-Sea MB/CB

- ^ أ ب Vision of Britain Archived 26 يناير 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Essex admin county (historic map Archived 30 سبتمبر 2007 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Essex County Council Archived 24 يناير 2008 at the Wayback Machine – District or Borough Councils

- ^ OPSI Archived 4 يناير 2009 at the Wayback Machine – The Essex (Boroughs of Colchester, Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock and District of Tendring) (Structural, Boundary and Electoral Changes) Order 1996

- ^ "Two of UK's top Leave districts in Essex". BBC News (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 24 June 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ أ ب Robert Young. (2009). Civic Heraldry of England and Wales. Essex Archived 3 فبراير 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ Essex WT website https://www.essexwt.org.uk/wildlife-explorer/wildflowers/cowslip Archived 25 سبتمبر 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bettley, James. (2008). Essex Explored: Essex Architecture. Archived 6 مايو 2011 at the Wayback Machine Essex County Council. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ "Colchester Castle Museum-Index". Colchestermuseums.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

وصلات خارجية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible motto list

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- إسكس

- Non-metropolitan counties

- أقاليم التصنيف الثاني في المملكة المتحدة

- مقاطعات إنگلترة

- English royal forests

- Home counties