موسكوفيوم

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المظهر | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| غير معروف | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الخصائص العامة | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الاسم، الرمز، الرقم | أنونپنتيوم, Uup, 115 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| النطق | /uːnuːnˈpɛntiəm/ oon-oon-PEN-tee-əm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تصنيف العنصر | غير معروفة | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المجموعة، الدورة، المستوى الفرعي | 15, 7, p | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الوزن الذري القياسي | [288] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| التوزيع الإلكتروني | [Rn] 5f14 6d10 7s2 7p3 (متوقع)[1] 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 18, 5 (متوقع) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| التسمية | IUPAC اسم عنصر نظامي | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الاكتشاف | المعهد المشترك للأبحاث النووية ومعمل لورنس ليڤرمور الوطني (2003) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الخصائص الطبيعية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الطور | صلب ((متوقع)[1]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الكثافة (بالقرب من د.ح.غ.) | 11 (متوقع)[1] g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نقطة الانصهار | ~700 ك, ~430 °C, ~810 (متوقع)[1] °F | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نقطة الغليان | ~1400 ك, ~1100 °س, ~2000 (متوقع)[1] °ف | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الخصائص الذرية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| حالات الأكسدة | 1, 3 (توقع)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| طاقات التأين | 1st: 538.4 (توقع)[1] كج·مول−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف القطر الذري | 200 (متوقع)[1] پم | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نصف قطر تساهمي | 162 (مـُقدّر)[2] pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| متفرقات | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رقم تسجيل كاس | 54085-64-2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| أكثر النظائر استقراراً | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المقالة الرئيسية: نظائر أنونپنتيوم | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

موسكوڤيوم وكانت تُعرف سابقاً بإسم الأنونپنتيوم Ununpentium هو الاسم المؤقت للعنصر الاصطناعي فائق الثقل في الجدول الدوري الذي له الرمز المؤقت Uup, والعدد الذري 115. كما أنه يعرف أيضا بمسمى تحت البزموث.

Moscovium is a synthetic chemical element; it has symbol Mc and atomic number 115. It was first synthesized in 2003 by a joint team of Russian and American scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia. In December 2015, it was recognized as one of four new elements by the Joint Working Party of international scientific bodies IUPAC and IUPAP. On 28 November 2016, it was officially named after the Moscow Oblast, in which the JINR is situated.[3][4][5]

Moscovium is an extremely radioactive element: its most stable known isotope, moscovium-290, has a half-life of only 0.65 seconds.[6] In the periodic table, it is a p-block transactinide element. It is a member of the 7th period and is placed in group 15 as the heaviest pnictogen. Moscovium is calculated to have some properties similar to its lighter homologues, nitrogen, phosphorus, arsenic, antimony, and bismuth, and to be a post-transition metal, although it should also show several major differences from them. In particular, moscovium should also have significant similarities to thallium, as both have one rather loosely bound electron outside a quasi-closed shell. Chemical experimentation on single atoms has confirmed theoretical expectations that moscovium is less reactive than its lighter homologue bismuth. Over a hundred atoms of moscovium have been observed to date, all of which have been shown to have mass numbers from 286 to 290.

مقدمة

تخليق نويات فائقة الثقل

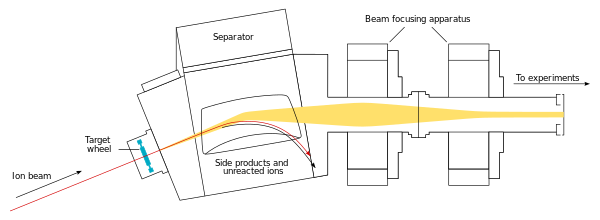

A superheavy[أ] atomic nucleus is created in a nuclear reaction that combines two other nuclei of unequal size[ب] into one; roughly, the more unequal the two nuclei in terms of mass, the greater the possibility that the two react.[12] The material made of the heavier nuclei is made into a target, which is then bombarded by the beam of lighter nuclei. Two nuclei can only fuse into one if they approach each other closely enough; normally, nuclei (all positively charged) repel each other due to electrostatic repulsion. The strong interaction can overcome this repulsion but only within a very short distance from a nucleus; beam nuclei are thus greatly accelerated in order to make such repulsion insignificant compared to the velocity of the beam nucleus.[13] The energy applied to the beam nuclei to accelerate them can cause them to reach speeds as high as one-tenth of the speed of light. However, if too much energy is applied, the beam nucleus can fall apart.[13]

Coming close enough alone is not enough for two nuclei to fuse: when two nuclei approach each other, they usually remain together for approximately 10−20 seconds and then part ways (not necessarily in the same composition as before the reaction) rather than form a single nucleus.[13][14] This happens because during the attempted formation of a single nucleus, electrostatic repulsion tears apart the nucleus that is being formed.[13] Each pair of a target and a beam is characterized by its cross section—the probability that fusion will occur if two nuclei approach one another expressed in terms of the transverse area that the incident particle must hit in order for the fusion to occur.[ت] This fusion may occur as a result of the quantum effect in which nuclei can tunnel through electrostatic repulsion. If the two nuclei can stay close for past that phase, multiple nuclear interactions result in redistribution of energy and an energy equilibrium.[13]

The resulting merger is an excited state[17]—termed a compound nucleus—and thus it is very unstable.[13] To reach a more stable state, the temporary merger may fission without formation of a more stable nucleus.[18] Alternatively, the compound nucleus may eject a few neutrons, which would carry away the excitation energy; if the latter is not sufficient for a neutron expulsion, the merger would produce a gamma ray. This happens in approximately 10−16 seconds after the initial nuclear collision and results in creation of a more stable nucleus.[18] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds. This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire its outer electrons and thus display its chemical properties.[19][ث]

الاضمحلال والكشف

The beam passes through the target and reaches the next chamber, the separator; if a new nucleus is produced, it is carried with this beam.[21] In the separator, the newly produced nucleus is separated from other nuclides (that of the original beam and any other reaction products)[ج] and transferred to a surface-barrier detector, which stops the nucleus. The exact location of the upcoming impact on the detector is marked; also marked are its energy and the time of the arrival.[21] The transfer takes about 10−6 seconds; in order to be detected, the nucleus must survive this long.[24] The nucleus is recorded again once its decay is registered, and the location, the energy, and the time of the decay are measured.[21]

Stability of a nucleus is provided by the strong interaction. However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens. At the same time, the nucleus is torn apart by electrostatic repulsion between protons, and its range is not limited.[25] Total binding energy provided by the strong interaction increases linearly with the number of nucleons, whereas electrostatic repulsion increases with the square of the atomic number, i.e. the latter grows faster and becomes increasingly important for heavy and superheavy nuclei.[26][27] Superheavy nuclei are thus theoretically predicted[28] and have so far been observed[29] to predominantly decay via decay modes that are caused by such repulsion: alpha decay and spontaneous fission.[ح] Almost all alpha emitters have over 210 nucleons,[31] and the lightest nuclide primarily undergoing spontaneous fission has 238.[32] In both decay modes, nuclei are inhibited from decaying by corresponding energy barriers for each mode, but they can be tunnelled through.[26][27]

Alpha particles are commonly produced in radioactive decays because mass of an alpha particle per nucleon is small enough to leave some energy for the alpha particle to be used as kinetic energy to leave the nucleus.[34] Spontaneous fission is caused by electrostatic repulsion tearing the nucleus apart and produces various nuclei in different instances of identical nuclei fissioning.[27] As the atomic number increases, spontaneous fission rapidly becomes more important: spontaneous fission partial half-lives decrease by 23 orders of magnitude from uranium (element 92) to nobelium (element 102),[35] and by 30 orders of magnitude from thorium (element 90) to fermium (element 100).[36] The earlier liquid drop model thus suggested that spontaneous fission would occur nearly instantly due to disappearance of the fission barrier for nuclei with about 280 nucleons.[27][37] The later nuclear shell model suggested that nuclei with about 300 nucleons would form an island of stability in which nuclei will be more resistant to spontaneous fission and will primarily undergo alpha decay with longer half-lives.[27][37] Subsequent discoveries suggested that the predicted island might be further than originally anticipated; they also showed that nuclei intermediate between the long-lived actinides and the predicted island are deformed, and gain additional stability from shell effects.[38] Experiments on lighter superheavy nuclei,[39] as well as those closer to the expected island,[35] have shown greater than previously anticipated stability against spontaneous fission, showing the importance of shell effects on nuclei.[خ]

Alpha decays are registered by the emitted alpha particles, and the decay products are easy to determine before the actual decay; if such a decay or a series of consecutive decays produces a known nucleus, the original product of a reaction can be easily determined.[د] (That all decays within a decay chain were indeed related to each other is established by the location of these decays, which must be in the same place.)[21] The known nucleus can be recognized by the specific characteristics of decay it undergoes such as decay energy (or more specifically, the kinetic energy of the emitted particle).[ذ] Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.[ر]

The information available to physicists aiming to synthesize a superheavy element is thus the information collected at the detectors: location, energy, and time of arrival of a particle to the detector, and those of its decay. The physicists analyze this data and seek to conclude that it was indeed caused by a new element and could not have been caused by a different nuclide than the one claimed. Often, provided data is insufficient for a conclusion that a new element was definitely created and there is no other explanation for the observed effects; errors in interpreting data have been made.[ز]تاريخ

تم اكتشاف كل من الأنونتريوم والأنونپنتيوم في 1 فبراير عام 2004، عن طريق عالم روسي في دوبنا المعهد المشترك للأبحاث النووية، وعلماء أمريكان في معمل لورنس ليڤرمور الوطني. ولا زال اكتشافهم ينتظر الموافقة عليه.[50]

أفاد فريق البحث أنهم قاموا بقذف (العنصر 92) أمريكيوم بالعنصر (رقم 20) كالسيوم لإنتاج أربعة ذرات من العنصر 115 أنون بينتيوم. هذه الذرات التي أعلنوا عنها، تضمحل إلى العنصر 113 أنونتريوم في أجزاء من الثانية. ثم يبقى الأنون تريوم لمدة 1.2 ثانية قبل إضمحلاله لعناصر طبيعية.

والإسم أنونپنتيوم هو إسم مؤقت بطربقة الاتحاد الدولي للكيمياء البحتة والتطبيقية لتسمية العناصر قياسياً.

في ديسمبر 2015، أعترف به كعنصر جديد من قبل الاتحاد الدولي للكيمياء البحتة والتطبيقية والاتحاد الدولي للفيزياء البحتة والتطبيقية. حتى الآن تم رصد ما يقارب 100 ذرة أنونپنتيوم، أظهرت جميعها عدد كتلي من 287 إلى 290.

أنونپنتيوم في الثقافة العامة

أنون بينتيوم تم وضعه نظريا داخل جزيرة الثبات. ويمكن أن يكون هذا سبب لذكر العنصر في الثقافة العامة قبل تصنيعه فعليا.

- في عالم نظرية تآمر كائنات طائرة غير معروفة خلال الثمانينيات والتسعينيات من القرن العشرين, أكد بوب لازار أن الأنونپنتيوم يتم إستخدامه كوقود للكائنات الطائرة الغير معروفة، كخطوة لإستخدام أنون هيكسينيوم كقذيفة، وأن نواتج إضمحلال أنون هيكسينيوم تتضمن ضد المادة. وهذه العمليات تعتبر غير فابلة للتصديق بمفاهيم الفيزياء النووية.

- وبالرجوع لهذا النوع من نظريات التآمر للكائنات الطائرة الغير معروفة, فقد ظهرت سلسلة من الألعاب الإلكترونية تسمى إكس-كوم والتي تفيد أن هناك عنصر يسمى إيليريوم-115 أو إيليريوم (الإسم خاطيء بهذا الشكل حيث انه يرجع لكتله الذرية بدلا من عدده الذري, والذي يعنى أن الإيليريوم سيكون بدون نيوترونات, وهذا غير قابل للحدوث).

- هناك نظير خيالي ثابت للأنون بينتيوم في لعبة المنطقة المنظلمة.

- هناك نظير خيالي ثابت للأنون بينتيوم في فيلم المركز.

- هناك نظير خيالي ثابت للعنصر 115 يعمل كمصدر لطاقة ألة الزمن في البرنامج التليفزيوني سبعة أيام.

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Haire, Richard G. (2006). "Transactinides and the future elements". In Morss; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 1-4020-3555-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Chemical Data. Ununpentium - Uup، الجمعية الكيميائية الملكية

- ^ Staff (30 November 2016). "IUPAC Announces the Names of the Elements 113, 115, 117, and 118". IUPAC. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (1 December 2016). "Four New Names Officially Added to the Periodic Table of Elements". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "IUPAC Is Naming The Four New Elements Nihonium, Moscovium, Tennessine, And Oganesson". IUPAC. 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- ^ Oganessian, Y.T. (2015). "Super-heavy element research". Reports on Progress in Physics. 78 (3): 036301. Bibcode:2015RPPh...78c6301O. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/78/3/036301. PMID 25746203. S2CID 37779526.

- ^ Krämer, K. (2016). "Explainer: superheavy elements". Chemistry World (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ "Discovery of Elements 113 and 115". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ Eliav, E.; Kaldor, U.; Borschevsky, A. (2018). "Electronic Structure of the Transactinide Atoms". In Scott, R. A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry (in الإنجليزية). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc2632. ISBN 978-1-119-95143-8. S2CID 127060181.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Dmitriev, S. N.; Yeremin, A. V.; et al. (2009). "Attempt to produce the isotopes of element 108 in the fusion reaction 136Xe + 136Xe". Physical Review C (in الإنجليزية). 79 (2): 024608. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.79.024608. ISSN 0556-2813.

- ^ Münzenberg, G.; Armbruster, P.; Folger, H.; et al. (1984). "The identification of element 108" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Physik A. 317 (2): 235–236. Bibcode:1984ZPhyA.317..235M. doi:10.1007/BF01421260. S2CID 123288075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Subramanian, S. (28 August 2019). "Making New Elements Doesn't Pay. Just Ask This Berkeley Scientist". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Ivanov, D. (2019). "Сверхтяжелые шаги в неизвестное" [Superheavy steps into the unknown]. nplus1.ru (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- ^ Hinde, D. (2017). "Something new and superheavy at the periodic table". The Conversation (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ Kern, B. D.; Thompson, W. E.; Ferguson, J. M. (1959). "Cross sections for some (n, p) and (n, α) reactions". Nuclear Physics (in الإنجليزية). 10: 226–234. Bibcode:1959NucPh..10..226K. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(59)90211-1.

- ^ Wakhle, A.; Simenel, C.; Hinde, D. J.; et al. (2015). Simenel, C.; Gomes, P. R. S.; Hinde, D. J.; et al. (eds.). "Comparing Experimental and Theoretical Quasifission Mass Angle Distributions". European Physical Journal Web of Conferences. 86: 00061. Bibcode:2015EPJWC..8600061W. doi:10.1051/epjconf/20158600061. ISSN 2100-014X.

- ^ "Nuclear Reactions" (PDF). pp. 7–8. Retrieved 2020-01-27. Published as Loveland, W. D.; Morrissey, D. J.; Seaborg, G. T. (2005). "Nuclear Reactions". Modern Nuclear Chemistry (in الإنجليزية). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 249–297. doi:10.1002/0471768626.ch10. ISBN 978-0-471-76862-3.

- ^ أ ب Krása, A. (2010). "Neutron Sources for ADS". Faculty of Nuclear Sciences and Physical Engineering. Czech Technical University in Prague: 4–8. S2CID 28796927.

- ^ Wapstra, A. H. (1991). "Criteria that must be satisfied for the discovery of a new chemical element to be recognized" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 63 (6): 883. doi:10.1351/pac199163060879. ISSN 1365-3075. S2CID 95737691.

- ^ أ ب Hyde, E. K.; Hoffman, D. C.; Keller, O. L. (1987). "A History and Analysis of the Discovery of Elements 104 and 105". Radiochimica Acta. 42 (2): 67–68. doi:10.1524/ract.1987.42.2.57. ISSN 2193-3405. S2CID 99193729.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Chemistry World (2016). "How to Make Superheavy Elements and Finish the Periodic Table [Video]". Scientific American (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- ^ Hoffman, Ghiorso & Seaborg 2000, p. 334.

- ^ Hoffman, Ghiorso & Seaborg 2000, p. 335.

- ^ Zagrebaev, Karpov & Greiner 2013.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 432.

- ^ أ ب Pauli, N. (2019). "Alpha decay" (PDF). Introductory Nuclear, Atomic and Molecular Physics (Nuclear Physics Part). Université libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Pauli, N. (2019). "Nuclear fission" (PDF). Introductory Nuclear, Atomic and Molecular Physics (Nuclear Physics Part). Université libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ Staszczak, A.; Baran, A.; Nazarewicz, W. (2013). "Spontaneous fission modes and lifetimes of superheavy elements in the nuclear density functional theory". Physical Review C. 87 (2): 024320–1. arXiv:1208.1215. Bibcode:2013PhRvC..87b4320S. doi:10.1103/physrevc.87.024320. ISSN 0556-2813.

- ^ Audi et al. 2017, pp. 030001-129–030001-138.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 439.

- ^ أ ب Beiser 2003, p. 433.

- ^ Audi et al. 2017, p. 030001-125.

- ^ Aksenov, N. V.; Steinegger, P.; Abdullin, F. Sh.; et al. (2017). "On the volatility of nihonium (Nh, Z = 113)". The European Physical Journal A (in الإنجليزية). 53 (7): 158. Bibcode:2017EPJA...53..158A. doi:10.1140/epja/i2017-12348-8. ISSN 1434-6001. S2CID 125849923.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 432–433.

- ^ أ ب ت Oganessian, Yu. (2012). "Nuclei in the "Island of Stability" of Superheavy Elements". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 337 (1): 012005-1–012005-6. Bibcode:2012JPhCS.337a2005O. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/337/1/012005. ISSN 1742-6596.

- ^ (1994) "Fission properties of the heaviest elements" in Dai 2 Kai Hadoron Tataikei no Simulation Symposium, Tokai-mura, Ibaraki, Japan., University of North Texas.

- ^ أ ب Oganessian, Yu. Ts. (2004). "Superheavy elements". Physics World. 17 (7): 25–29. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/17/7/31. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ Schädel, M. (2015). "Chemistry of the superheavy elements". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 373 (2037): 20140191. Bibcode:2015RSPTA.37340191S. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0191. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 25666065.

- ^ Hulet, E. K. (1989). "Biomodal spontaneous fission" in 50th Anniversary of Nuclear Fission, Leningrad, USSR..

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Rykaczewski, K. P. (2015). "A beachhead on the island of stability". Physics Today. 68 (8): 32–38. Bibcode:2015PhT....68h..32O. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2880. ISSN 0031-9228. OSTI 1337838.

- ^ Grant, A. (2018). "Weighing the heaviest elements". Physics Today (in الإنجليزية). doi:10.1063/PT.6.1.20181113a. S2CID 239775403.

- ^ Howes, L. (2019). "Exploring the superheavy elements at the end of the periodic table". Chemical & Engineering News (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- ^ أ ب Robinson, A. E. (2019). "The Transfermium Wars: Scientific Brawling and Name-Calling during the Cold War". Distillations (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ "Популярная библиотека химических элементов. Сиборгий (экавольфрам)" [Popular library of chemical elements. Seaborgium (eka-tungsten)]. n-t.ru (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-01-07. Reprinted from "Экавольфрам" [Eka-tungsten]. Популярная библиотека химических элементов. Серебро — Нильсборий и далее [Popular library of chemical elements. Silver through nielsbohrium and beyond] (in الروسية). Nauka. 1977.

- ^ "Nobelium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- ^ أ ب Kragh 2018, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kragh 2018, p. 40.

- ^ أ ب Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T.; Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (1993). "Responses on the report 'Discovery of the Transfermium elements' followed by reply to the responses by Transfermium Working Group" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (8): 1815–1824. doi:10.1351/pac199365081815. S2CID 95069384. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (1997). "Names and symbols of transfermium elements (IUPAC Recommendations 1997)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 69 (12): 2471–2474. doi:10.1351/pac199769122471.

- ^ [1]

وصلات خارجية

المصادر

- ويكيبيديا الإنجليزية.

| أظهر الجدول الدوري |

|---|

خطأ استشهاد: وسوم <ref> موجودة لمجموعة اسمها "lower-alpha"، ولكن لم يتم العثور على وسم <references group="lower-alpha"/>